Abstract

Objective

To examine the cost of care during the first year after a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, estimate the sources of cost, and explore the out-of-pocket costs.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, cohort study of women with ovarian cancer diagnosed from 2009–2012 who underwent both surgery using the Truven Health MarketScan database. This database is comprised of patients covered by commercial insurance sponsored by over 100 employers in the United States. Medical expenditures, including physician reimbursement, for a 12-month period beginning on the date of surgery were estimated. All payments were examined, including out-of-pocket costs for patients. Payments were divided into expenditures for inpatient care, outpatient care (including chemotherapy), and outpatient drug costs. The 12-month treatment period was divided into 3 phases: surgery-30 days (operative period), 1–6 months (adjuvant therapy), and 6–12 months after surgery. The primary outcome was the overall cost of care within the first year of diagnosis of ovarian cancer, while secondary outcomes included assessment of factors associated with cost.

Results

A total of 26,548 women with ovarian cancer who underwent surgery were identified. After exclusion of patients with incomplete insurance enrollment/coverage, those who did not undergo chemotherapy, and those with capitated plans, our cohort consisted of 5,031 women. The median total medical expenditures per patient during the first year after the index procedure was $93,632 (interquartile range [IQR] $62,319–140,140). Inpatient services accounted for $30,708 (IQR, $20,102–51,107; 37.8%) in expenditures, outpatient services $52,700 (IQR, $31,210–83,206; 58.3%) and outpatient drug costs $1,814 (IQR, $603–4,402; 3.8%). The median out-of-pocket expense was $2988 (IQR, $1649–5088). This included $1509 (IQR, $705–2878) for outpatient services, $589 (IQR, $3–1715) for inpatient services, and $351 (IQR, $149–656) for outpatient drug costs.

Conclusion

The average cost of care for women with ovarian cancer in the first year after surgery is approximately $100,000. Patients bear approximately 3% of these costs in the form of out-of-pocket expenses.

Introduction

Cancer remains a leading cause of death in the U.S. and cancer care is one of the fastest growing fields in healthcare.1 The cost of cancer care in 2010 was $124.6 billion and is projected to increase to $173 billion by 2020 with cancer drug prices and acute hospital care as the main drivers.1 Beyond overall costs of care, cancer patients and their families experience high out-of-pocket expenditures that often affect quality of life and force patients to alter or delay cancer care in an attempt to avoid or lower out-of-pocket costs.1

The treatment of ovarian cancer is multimodal and intensive. After diagnosis, women usually undergo surgery as well as receive chemotherapy.2 Women with recurrent ovarian cancer are typically treated with multiple lines of chemotherapy over months to years.3 Recently, new, costly biologic agents, both oral and intravenous drugs, have been approved for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer and a number of new agents are on the horizon.4,5

Despite the intensity of treatment of ovarian cancer, a paucity of data is available to describe the cost of care.6–9 A recent study of Medicare beneficiaries estimated that the mean cost of care during the first year after diagnosis was approximately $66,000.8 Estimates of how these costs are shared by patients are limited. The objective of the study was to examine the cost of care during the first year after diagnosis, to estimate the sources of cost, and to investigate the out-of-pocket costs that women with ovarian cancer experience.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of women with ovarian cancer receiving both surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy using the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database (Ann Arbor, MI).10 The data includes patients enrolled in commercial insurance sponsored by over 100 employers in the United States. The database captures claims on more than 115 million commercially insured patients, including inpatient claims, outpatient claims, and prescription drug use. This database allows for the longitudinal study of patient data and enrollment.10,11. The study used de-identified data and was deemed exempt by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board.

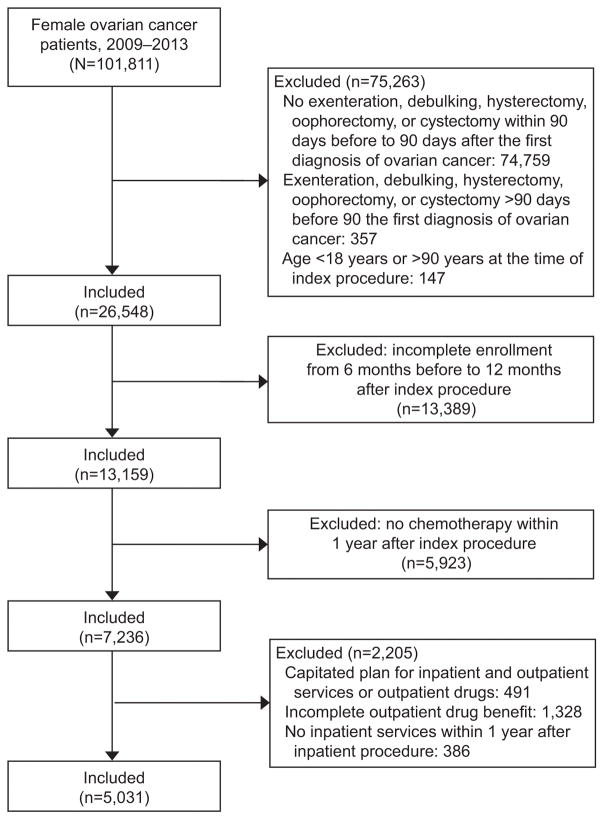

The eligibility criteria for inclusion into our study cohort included women aged 18–90 years who had ovarian cancer (International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] 183.x) and underwent ovarian cancer-directed surgery, including debulking, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, cystectomy or exenteration, from 2009 to 2012 (Figure 1). We identified 101,811 patients with a ovarian cancer and excluded 74,759 of them due to an absence of surgery within 90 days before or after the first diagnosis (Figure 1). For patients who had multiple surgical claims, the first encounter was selected as the index date for surgery. We excluded patients who had the surgery more than 90 days prior to the first diagnostic claim of ovarian cancer (N=357) and patients who had incomplete enrollment for inpatient and outpatient services or outpatient drug benefit from 6 months prior to 1 year after the surgery (N=13, 389). We excluded patients who did not have any chemotherapy (N=5,923) or did not have any inpatient services during the 1-year period after the surgery (N=386). To allow ascertainment of the contribution of individual cost centers, we excluded patients who were under capitated plans for inpatient and outpatient services or outpatient drugs (N=491).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart for the cohort.

Demographic and clinical characteristics included age (<40, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, ≥70 years), year of the surgery (2009, 2010, 2011, and 2012), and region (Northeast, North central, South, West, unknown). Comorbidity was measured using the Charlson comorbidity score12 and classified as 0, 1, or ≥2. Surgery was classified into mutually exclusive categories following the hierarchy of exenteration, debulking, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and cystectomy.

The primary outcomes of this study were the overall as well as out-of-pocket cost of care within the first year of diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Secondary outcomes included the cost of inpatient care, outpatient care, outpatient drugs during the initial year after diagnosis. Medical expenditures were defined as all reimbursed costs. This included all reimbursed costs from the primary insurance providers, cost sharing from patients, and benefits received from other insurance carriers. Out-of-pocket (OOP) payment was calculated as the sum of deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance. Coordination of benefits and other savings (COB) was estimated as third party payment from a source other than the patient or the submitting plan, such as the Medicare paid amount for Medicare beneficiaries. Insurance liability was the payment received by the provider excluding OOP and COB. Costs were classified as inpatient costs for all inpatient care, outpatient costs for care received in the outpatient setting including intravenous chemotherapy and outpatient drug costs for oral drugs. All facility and physician claims were included in the analysis.

We examined the medical expenditures from the time of surgery until 1 year after the procedure. A secondary analysis was also performed in which costs were stratified into 3 periods to approximate the phases of care of ovarian cancer: surgery to 30 days postoperative (operative care phase), 31 days to 6 months post procedure (adjuvant chemotherapy phase), and 6 months to 1 year after the index operation. This classification schema was based on the general course of treatment for patients with ovarian cancer treatment. The first 30 days after surgery generally encompasses perioperative care, while months 1–6 after diagnosis roughly correspond to the time of treatment with chemotherapy which is followed by surveillance. We recognize that this is an approximation and care is highly variable. For each period, OOP, insurance liability and COB were estimated. Each reimbursement was stratified into a number of cost centers including inpatient claims, outpatient service claims, and outpatient pharmaceutical claims. Outpatient services included all services a patient received in an outpatient setting, including chemotherapy infusions. Similarly, outpatient drugs covered all oral drugs that a patient filled. Total cost was calculated as the sum of the corresponding sources of payments. All costs were adjusted for inflation and reported in 2013 dollars. To mitigate the effect of outliers, all cost data were winsorized; patients with costs <3rd percentile were set at the 3rd percentile and patients with costs >97th percentile set at the 97th percentile.13,14

The demographic and clinical characteristics were reported descriptively as number and percentage. The total, OOP, and insurance expenditures were reported as medians with interquartile range among the patients who had inpatient, outpatient services and outpatient drugs in each period. The median expenditures were compared by year of diagnosis and region using Kruskal-Wallis tests. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All tests were two-sided. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 5,031 patients were identified. The majority of women were between the ages of 50–69 years (Table 1). A total of 81.8% had a comorbidity score of 0, 14.4% had a score of 1 and 3.9% had a score of ≥2. Within the cohort, 408 (8.1%) had a chemotherapy claim prior to the index operation.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| All | 5,031 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||

| <40 | 317 | 6.3 |

| 40–49 | 850 | 16.9 |

| 50–59 | 1,785 | 35.5 |

| 60–69 | 1,382 | 27.5 |

| ≥70 | 697 | 13.9 |

| Year of index procedure | ||

| 2009 | 711 | 14.1 |

| 2010 | 1,513 | 30.1 |

| 2011 | 1,598 | 31.8 |

| 2012 | 1,209 | 24.0 |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 1,158 | 23.0 |

| North Central | 1,297 | 25.8 |

| South | 1,682 | 33.4 |

| West | 831 | 16.5 |

| Unknown | 63 | 1.3 |

| Comorbidity (Charlson) | ||

| 0 | 4,113 | 81.8 |

| 1 | 724 | 14.4 |

| ≥2 | 194 | 3.9 |

| Surgery | ||

| Exenteration | 64 | 1.3 |

| Debulking | 2,556 | 50.8 |

| Hysterectomy | 1,957 | 38.9 |

| Oophorectomy | 445 | 8.9 |

| Cystectomy | 9 | 0.2 |

The median total medical expenditures per patient during the first year after the index procedure was $93,632 (IQR 62,319–140,140) (Table 2). Inpatient services accounted for $30,708 (IQR, $20,102–51,107) in expenditures, outpatient services $52,700 (IQR, $31,210–83,206) and outpatient drug costs $1814 (IQR, $603–4402). Among all costs, outpatient services accounted for 58.3%, inpatient services 37.8%, and outpatient drug costs 3.8%.

Table 2.

Medical expenditures (in US dollars) during the 1-year post-operative period for newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients.

| Total | OOP | Insurance | COB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | |

| Total | 93,632 | (62,319–140,140) | 2,988 | (1,649–5,088) | 81,628 | (43,972–132,100) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Inpatient services | 30,708 | (20,102–51,107) | 589 | (3–1,715) | 25,727 | (13,485–44,327) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Outpatient services | 52,700 | (31,210–83,206) | 1,509 | (705–2,878) | 45,201 | (19,127–78,078) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Outpatient drugs | 1,814 | (603–4,402) | 351 | (149–656) | 1,360 | (370–3,662) | 0 | (0–0) |

OOP (out-of-pocket), insurance liability, and COB (coordination of benefits and other savings) for inpatient, outpatient services and outpatient drugs were winsorized at 3rd & 97th percentiles, then summed to get the inpatient, outpatient services, outpatient drugs, and total medical expenditures (including inpatient, outpatient services and outpatient drugs).

The median out-of-pocket expense was $2988 (IQR, $1649–5088). This included $1509 (IQR, $705–2878) for outpatient services, $589 (IQR, $3–1715) for inpatient services and $351 (IQR, $149–656) for outpatient drug costs. The median insurance cost was $81,628 (IQR, $43,972–132,100) and had a similar distribution.

When stratified by time since surgery, the total treatment cost within the first 30 days of the index procedure was a median of $30,501 (IQR, $21,623–44,167) per patient (Table 3). Median overall costs were $38,795 (IQR, $22,737–62,762) during the period of 1–6 months after surgery, and $12,469 (IQR, $4639–33,107) from 6 to 12 months. Both out-of-pocket expenses and insurance costs were greatest during the period from 1–6 months followed by the immediate postoperative period. During the period from surgery to 30 days, inpatient services made up the greatest majority of insurance costs and out-of-pocket expenses. In contrast, outpatient services were the dominant driver of cost during the period from 31 days to 6 months.

Table 3.

Medical expenditures (in US dollars) during various post-operation periods for newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients.

| N | Total | OOP | Insurance | COB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | ||

| Day of operation to 30 days post-operation | |||||||||

| Total | 5,031 | 30,501 | (21,623–44,167) | 777 | (190–1,905) | 26,783 | (14,970–39,797) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Inpatient services | 4,806 | 25,401 | (17,787–37,901) | 518 | (0–1,544) | 21,900 | (12,561–33,825) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Outpatient services | 4,873 | 4,213 | (1,410–8,379) | 59 | (5–230) | 3,077 | (728–7,746) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Outpatient drugs | 5,031 | 131 | (29–494) | 40 | (12–85) | 76 | (5–400) | 0 | (0–0) |

| 1 to 6 months post-operation | |||||||||

| Total | 5,031 | 38,795 | (22,737–62,762) | 837 | (351–1,903) | 33,595 | (13,929–60,029) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Inpatient services | 1,296 | 17,477 | (9,079–31,112) | 0 | (0–373) | 15,623 | (6,666–30,393) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Outpatient services | 5,030 | 32,105 | (18,538–50,573) | 523 | (155–1,446) | 27,916 | (10,549–48,535) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Outpatient drugs | 5,031 | 751 | (188–2,181) | 159 | (53–317) | 543 | (93–1,831) | 0 | (0–0) |

| 6 months to 1 year post-operation | |||||||||

| Total | 5,031 | 12,469 | (4,639–33,107) | 593 | (240–1,287) | 8,415 | (2,902–27,014) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Inpatient services | 944 | 20,592 | (10,768–39,778) | 0 | (0–479) | 14,362 | (3,669–31,963) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Outpatient services | 5,000 | 9,459 | (3,662–24,989) | 362 | (112–945) | 6,568 | (1,917–19,347) | 0 | (0–0) |

| Outpatient drugs | 5,031 | 450 | (84–1,486) | 111 | (25–267) | 302 | (31–1,159) | 0 | (0–0) |

The analyses of median and IQR were limited to the patients (N) who utilized the inpatient, outpatient services or outpatient drugs in each period. For each period, OOP (out-of-pocket), insurance liability, and COB (coordination of benefits and other savings) for inpatient, outpatient services and outpatient drugs were winsorized at 3rd & 97th percentiles, then summed to get inpatient, outpatient services, outpatient drugs, and total medical expenditures (including inpatient, outpatient services and outpatient drugs).

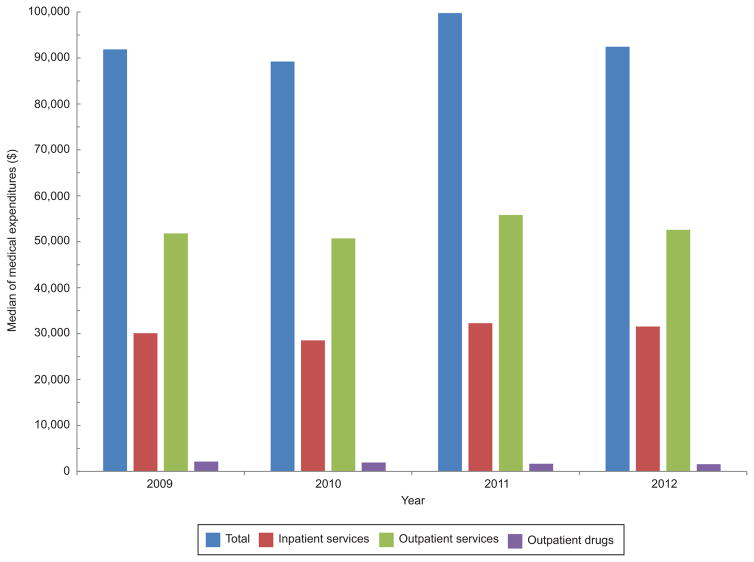

When medical expenditures were broken down by year, the median of total medical expenditures were highest in 2011 at $99,775 (IQR 65,848–146,893) along with inpatient and outpatient services expenditures (Figure 2). However, the median total outpatient drug costs gradually decreased from $2,163 in 2009 to $1,584 in 2012. While the median of total costs increased in 2011, median of total out-of-pocket costs varied from $3,076 in 2009 to $2,780 in 2012.

Figure 2.

Median (interquartile range) medical expenditures in U.S. dollars during the 1-year postoperative period stratified by year and service category. Medians of inpatient and outpatient services, outpatient drugs, and total medical expenditures were significantly different by year of diagnosis (P<.001 for all).

The median of total medical expenditures during the first year after the index procedure was highest in the Northeast region ($102,055, IQR 68,851–150,195) and lowest in the North Central region ($87,468, IQR 56,068–130,028) (Table 4). The out-of-pocket expenditures were highest in South and lowest in the Northeast.

Table 4.

Medical expenditures during the 1-year post-operation period by region for newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients.

| Northeast | North Central | South | West | Unknown | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | ||

| Total | 102,055 | (68,851–150,195) | 87,468 | (56,068–130,028) | 91,140 | (60,228–137,127) | 100,536 | (65,358–148,707) | 94,561 | (71,922–138,265) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient services | 33,773 | (21,251–56,455) | 28,562 | (18,640–46,575) | 28,468 | (19,348–46,702) | 34,099 | (21,899–59,795) | 35,298 | (22,575–58,218) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient services | 54,407 | (34,190–86,283) | 47,823 | (28,015–79,216) | 53,688 | (31,201–82,487) | 55,128 | (31,469–85,646) | 59,307 | (43,112–84,737) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient drugs | 2,507 | (803–5,773) | 1,668 | (522–4,282) | 1,669 | (604–3,950) | 1,577 | (482–4,109) | 2,318 | (843–5,566) | <0.001 |

OOP (out-of-pocket), insurance liability, and COB (coordination of benefits and other savings) for inpatient, outpatient services and outpatient drugs were winsorized at 3rd & 97th percentiles, then summed to get inpatient, outpatient services, outpatient drugs, and total medical expenditures (including inpatient, outpatient services and outpatient drugs).

Discussion

We demonstrated that the average cost of care for women with ovarian cancer in the first year after surgery is over $93,000 and rose to nearly $100,000 by 2011. Patients bear approximately 3% of these costs in some form of out-of-pocket costs. A large proportion of expenditures occur in both the immediate perioperative period as well as in the period from 31 days to 6 months after surgery.

Most estimates suggest that the cost of cancer care will continue to increase in the next decade. The rising costs are driven in large part by new drugs and diagnostic procedures. According to one report, from 2004 to 2014 the proportion of cost associated with inpatient care declined, while the proportion of spending for new chemotherapy drugs, specifically biologics, increased from 2% to 7%.15 High drug costs are due in large part to the introduction of novel agents to the marketplace.16 Similarly, diagnostic imaging, specifically the use of positron emission tomography, has become a substantial driver of cancer care costs.17

The cost of care among other types of cancer varies greatly. In 2008, Yaboff et al estimated the total cost of cancer care for over 14 different cancer types.18 In women, brain cancer ($69,908) was the only cancer that had a higher average cost of care than ovarian cancer ($51,548). Other common cancers in women were less costly in the first year with breast costing an average of $11,278, colorectal $29,930, and lung $34,828.18

Relatively little data has examined the cost of care for ovarian cancer.. The mean payments for Medicare beneficiaries with ovarian cancer within the first year of diagnosis was $65,908, Treatment with guideline concordant care was associated with lower costs in this cohort.8 These findings are in line with our data in which payments of $93,000 within the first year of diagnosis for commercially insured women with ovarian cancer.

Given the rising costs of cancer care, there has been heightened attention on out-of-pocket expenses that patients and their families incur. In an analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary survey data, Medicare patients with cancer paid $4727 in out-of-pocket expenses over two years, compared to the non-cancer cohort who paid $3209.19 However, a similar study showed that Medicare beneficiaries newly diagnosed with cancer but without supplemental insurance incurred an even higher annual out-of-pocket cost of $8115.20 We found that the median out-of-pocket cost for patients during the first year of treatment was $2988.

The high out-of-pocket expenses that cancer patients bear is often associated with significant financial hardship, so called financial toxicity. An analysis of patients with multiple myeloma, 36% had to apply for financial assistance, 46% used savings to pay for treatment and 21% had to borrow money to cover the costs of medications.21 Medical bankruptcy, defined as debt incurred from health-related expenditures, remains the leading cause of bankruptcy in the U.S. A recent study demonstrated that individuals with a cancer diagnosis were 2.5 times more likely to file for bankruptcy than individuals without cancer.22 Clearly out-of-pocket expenses can have a significant impact on patients and their families.

While our study benefits from the inclusion of a large sample of women with ovarian cancer, we acknowledge a number of important limitations. First, while our analysis relied on high quality claims data, there is the possibility that costs may have been undercaptured in a small number of women. Second, the out-of-pocket expenditures reported represent only a portion of the complete financial burden that women with ovarian cancer incur. We are unable to capture the costs of traveling for care, costs incurred by family members, and lost earnings. Third, our analysis focused on commercially insured patients; thus, these findings are likely not generalizable to Medicare recipients, Medicaid beneficiaries and patients covered by other types of plan. Additionally, women with incomplete enrollment were excluded so these findings cannot be applied to women who do not have continuous coverage. Those women excluded likely experienced higher out-of-pocket costs. Lastly, MarketScan does not provide detailed demographic data, so we were not able to assess the association between cost and race, histology, stage and other clinical and demographic characteristics.

Given the substantial overall costs as well as out-of-pocket expenditures for women with ovarian cancer, .these data help to inform the discussion about strategies to reduce the cost of ovarian cancer care and to address the personal financial burden experienced by patients and their families. These estimates provide the groundwork for future efforts to help reduce the cost and improve the quality of ovarian cancer care.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright (NCI R01CA169121-01A1) and Dr. Hershman (NCI R01 CA166084) are recipients of grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Hershman is the recipient of a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation/Conquer Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Wright has served as a consultant for Clovis Oncology and Tesaro. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011;103:117–28. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright JD, Ananth CV, Tsui J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of upfront treatment strategies in elderly women with ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1246–54. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinkelspiel HE, Champer M, Hou J, et al. Long-term mortality among women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2015;138:421–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: The AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1302–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1382–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowland MR, Lesnock JL, Farris C, Kelley JL, Krivak TC. Cost-utility comparison of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus primary debulking surgery for treatment of advanced-stage ovarian cancer in patients 65 years old or older. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:763, e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sfakianos GP, Havrilesky LJ. A review of cost-effectiveness studies in ovarian cancer. Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2011;18:59–64. doi: 10.1177/107327481101800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urban RR, He H, Alfonso-Cristancho R, Hardesty MM, Goff BA. The Cost of Initial Care for Medicare Patients With Advanced Ovarian Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:429–37. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forde GK, Chang J, Ziogas A, Tewari K, Bristow RE. Costs of treatment for elderly women with advanced ovarian cancer in a Medicare population. Gynecologic oncology. 2015;137:479–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truven Health Analytics. [Accessed January 28th, 2017];MarketScan. at http://truvenhealth.com/your-healthcare-focus/life-sciences/marketscan-databases-and-online-tools.

- 11.Wright JD, Hou JY, Burke WM, et al. Utilization and Toxicity of Alternative Delivery Methods of Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016;127:985–91. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Association between hospital conversions to for-profit status and clinical and economic outcomes. Jama. 2014;312:1644–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ly DP, Jha AK, Epstein AM. The association between hospital margins, quality of care, and closure or other change in operating status. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1291–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1815-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyenson BSFK, Pelizzari PM. Cost Drivers of Cancer Care: A Retrospective Analysis of Medicare and Commercially Insured Population Claim Data 2004–2014. Seattle, WA, USA: Milliman Report; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bach PB. Limits on Medicare’s ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:626–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0807774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Czernin J. Contribution of imaging to cancer care costs. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2011;52(Suppl 2):86S–92S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.085621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:630–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidoff AJ, Erten M, Shaffer T, et al. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1257–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narang AK, Nicholas L. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JAMA Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huntington SF, Weiss BM, Vogl DT, et al. Financial toxicity in insured patients with multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional pilot study. Lancet Haematol. 2015;2:e408–16. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]