Abstract

Use of subject-specific axes of rotation may improve predictions generated by kinematic models, especially for joints with complex anatomy, such as the tibiotalar and subtalar joints of the ankle. The objective of this study was twofold. First, we compared the axes of rotation between generic and subject-specific ankle models for ten control subjects. Second, we quantified the accuracy of generic and subject-specific models for predicting tibiotalar and subtalar joint motion during level walking using inverse kinematics. Here, tibiotalar and subtalar joint kinematics measured in vivo by dual-fluoroscopy served as the reference standard. The generic model was based on a cadaver study, while the subject-specific models were derived from each subject's talus reconstructed from computed tomography images. The subject-specific and generic axes of rotation were significantly different. The average angle between the modeled axes was 12.9°±4.3° and 24.4°±5.9° at the tibiotalar and subtalar joints, respectively. However, predictions from both models did not agree well with dynamic dual-fluoroscopy data, where errors ranged from 1.0° to 8.9° and 0.6° to 7.6° for the generic and subject-specific models, respectively. Our results suggest that methods that rely on talar morphology to define subject-specific axes may be inadequate for accurately predicting tibiotalar and subtalar joint kinematics.

Keywords: ankle, biomechanics, dynamic imaging, gait, motion analysis, model

Introduction

Analyzing human movement often requires the definition of a priori kinematic models that describe joint motion. These models can be generic for the purpose of describing joint kinematics of an average subject, or subject-specific to predict joint kinematics for an individual subject. Subject-specific models may be necessary when examining complex joints with highly variable motion, such as the tibiotalar and subtalar joints of the ankle. For example, subject-specific models could elucidate how gender, bone morphology, and ligament laxity, contribute to variability in healthy and pathologic ankle kinematics. Representation of subject-specific anatomy may be particularly important when modeling the ankle due to the highly variable morphology of the talus.24,35 Multiple studies have described methods to define subject-specific axes of rotation at the tibiotalar and subtalar joints.2,9,15,16,28,32,36 These include anatomical landmark methods, which use palpable bony landmarks to estimate the location and orientation of joint axes9,10; functional methods, which require axes be fitted to recorded motion15,31; imaging methods, which directly measure helical axes of rotation2,14,17,32; as well as optimization methods, which fit a pre-defined joint model to a measured motion.16,28,36

Many of these subject-specific methods require kinematic data to define joint axes of rotation. Often, ankle joint axes of rotation are calculated from kinematic data obtained during passive motions, but this is problematic as axes defined based on a passive motion may not be representative of weight-bearing activities, such as gait. As an example, helical axes of rotation are often defined by independently evaluating dorsiflexion/plantarflexion motion (i.e., planar motion in the sagittal plane) and inversion/eversion motion (i.e., planar motion in the coronal plane).32 Similarly, some functional methods record segment motion during unique activities that aim to isolate single-joint motion15, but this does not necessarily represent the triplanar motion that the ankle naturally facilitates.25 Alternatively, three-dimensional (3D) bone geometry, generated from medical image data, can define subject-specific axes using methods independent of the collected kinematic data.26 However, the extent to which subject-specific axes defined from 3D bone geometry improve inverse kinematic simulations is unknown.

The objective of this study was twofold. First, we compared the axes of rotation between generic and subject-specific ankle models for ten control subjects. Here, the generic model was a widely used kinematic model based on a cadaver study and utilized hinge joints to represent the tibiotalar and subtalar joints,9 while the subject-specific model was defined based on talar morphology.26 Thus, the generic model incorporated axes of rotation that were equivalently defined across all subjects, while the subject-specific models incorporated unique axes that varied across subjects. Second, we quantified the accuracy of generic and subject-specific models for predicting tibiotalar and subtalar joint motion during level walking using inverse kinematics derived from skin-marker data. Here, tibiotalar and subtalar joint kinematics measured in vivo by dual-fluoroscopy served as the reference standard. Given that the morphology of the talus is highly variable across individuals,24,35 we hypothesized that there would be significant differences in axes of rotation between the generic and subject-specific models. We further hypothesized that the subject-specific models would provide a more accurate representation of in vivo motion and would thereby predict joint kinematics in better agreement with the dual-fluoroscopy results than generic models.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The experimental data used in this study have been previously described.23,29 Briefly, ten healthy, young adults (5 male, 5 female; age 30.9 ± 7.2 years; height 1.72 ± 0.11 m; weight 70.2 ± 15.9 kg) participated in this study. Each subject provided written informed consent and the experimental protocol was approved by University of Utah's Institutional Review Board (IRB#65620). All subjects were screened for foot and ankle pathology, including varus/valgus hindfoot malalignment, osteophytes, and/or osteoarthritis, using plain film radiographs.

Computed Tomography Scans and 3D Reconstruction of Bone Geometry

Computed tomography (CT) images were acquired for each subject using a single-source CT (SOMATOM Definition™, Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA). Each scan included the foot, ankle, and distal tibia (1.0 mm slice thickness, 366 ± 65.2 mm field of view, 512 × 512 acquisition matrix, 100 kV, and 16-73 mA). To generate 3D reconstructions of the tibia, talus, and calcaneus bone geometry, CT images were manually segmented using commercial software (Amira, v5.6, Visage Imaging, San Diego, CA).

Skin-Marker & Dual-Fluoroscopy Motion Capture

Reflective skin-markers were placed on the lower limb using a modified Helen-Hayes marker set.12 These markers tracked the position of the pelvis, thigh, calf, and foot segments. It should be noted that this marker set assumes the rearfoot, midfoot, and forefoot exist as a single, rigid segment. This marker set was evaluated because many gait studies assume a rigid-foot. On the ankle and foot, markers were placed on the medial and lateral malleoli, calcaneal tuberosity, immediately proximal to the second and fifth metatarsophalangeal joints, dorsal web space between the fourth and fifth metatarsals, and the dorsal-medial aspect at the proximal base of the first metatarsal.

Simultaneous imaging using near-infrared cameras and a custom dual-fluoroscopy system was recorded for each subject during 1.0 m/s barefoot, treadmill walking. These time-synchronized data were collected at 250-300 Hz. The near-infrared cameras, which consisted of a 10-camera Vicon motion capture system running Nexus 1.8.5 (Vicon Motion Systems; Oxford UK), measured the trajectories of the reflective markers. The custom dual-fluoroscopy system, which has been previously described and validated,37 imaged the tibia, talus, and calcaneus. The dual-fluoroscopy system could not capture the entire stance phase of gait, as the treadmill belt moved the foot out of the fluoroscopes' combined field of view prior to the completion of stance. As a result, toe-off and heel-strike were imaged as separate activities. Each subject completed two trials per activity (i.e., 2 toe-off and 2 heel-strike trials). For one subject, only 1 toe-off trial was analyzed due to missing data.

Marker trajectories were post-processed in Nexus (v. 1.8.5, Vicon Motion Systems; Oxford UK). Gaps in marker trajectories were filled using a spline fitting algorithm. Trajectories were low-pass filtered at 6 Hz. Dual-fluoroscopy data was post-processed using model-based markerless tracking.3 Positions of the tibia, talus, and calcaneus were calculated from model-based markerless tracking results, which were smoothed using a fourth-order Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 10 Hz. This protocol has been previously validated for the ankle and quantifies the positions and orientations of the tibia, talus, and calcaneus with sub-millimeter and sub-degree accuracy.37

Definition of Generic & Subject-Specific Models

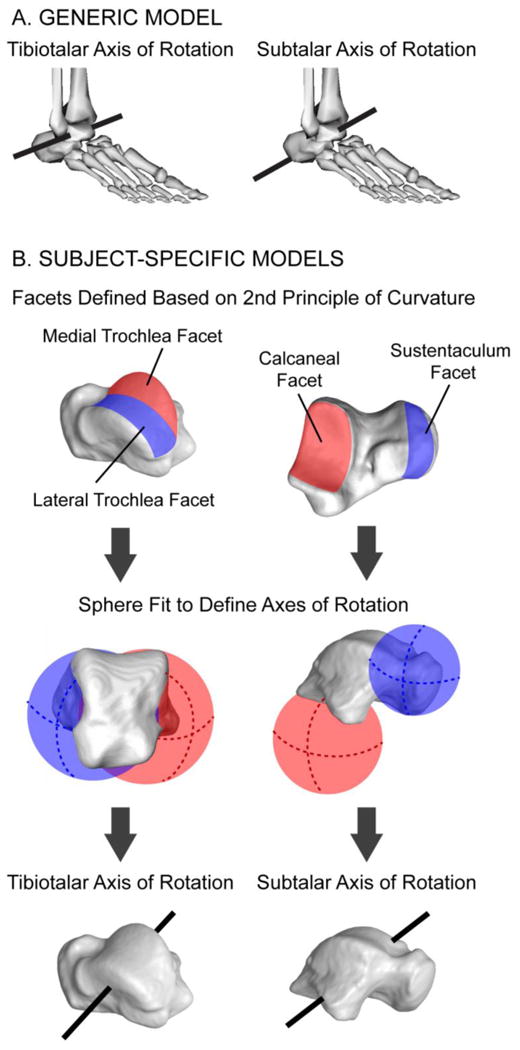

The generic model was based on a validated model of the lower limb, and included only generic bone geometry and joint kinematics.1 Importantly, based on average axes of rotation derived from passive joint motions measured in a cadaveric experiment,9 the tibiotalar joint (motion of the talus segment relative to a rigidly fixed tibia-fibula segment) was defined by one axis of rotation that primarily defined dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, while the subtalar joint (motion of the calcaneus segment relative to the talus segment) included one axis of rotation that primarily defined inversion/eversion (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation in the (A) generic and (B) subject-specific model. For the generic model, axes were defined based on Inman et al. (1976). For the subject-specific models, axes were defined using a sphere fitting method developed by Parr et al. (2012), which utilized each subject's talus geometry to define unique axes of rotation for the tibiotalar and subtalar joints.

The subject-specific models were defined using a method developed by Parr et al.26, in which the tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation are calculated from the bone geometry of the talus (Fig. 1B). Specifically, the orientation of the tibiotalar axis of rotation is defined as the vector between the center of two spheres, separately fit to the medial and lateral portions of the trochlea facet of the talus. The orientation of the subtalar axis of rotation is defined as the vector between two spheres, separately fit to the sustentaculum and calcaneal facets of the talus. The origin of each axis is defined as the midpoint between the two spheres used in defining the axis orientation. The trochlea, sustentaculum, and calcaneal facets were semi-automatically defined using the second principle of curvature, as calculated by an open-source program (Postview v. 1.9.1; Salt Lake City, UT).18 Spheres were fit to each facet using a least squares approach.11 Parr et al.26 demonstrated that axes of rotation calculated from the bone geometry of the talus are in good agreement, but not identical to those calculated from in vitro studies, which relied on range of motion measurements.2,19,20

For each subject, one generic and one subject-specific model were defined. Each model was scaled by the subject's height and weight using a measurement-based scaling method.6 In this method, scale factors of each segment were calculated as the ratio of distances between markers on the model and those measured experimentally. For example, the distance between markers on the lateral condyle of the tibia and the lateral malleoli were used to determine the length of the tibia segment.

Calculation of Joint Angles

To predict joint angles using the generic and subject-specific models, inverse kinematic simulations (OpenSim, v. 3.3)6 were performed separately for each combination of model, subject, activity, and trial (80 simulations total). The inverse kinematic simulations utilized all recorded skin-marker trajectory data to calculate rotation angles about the two axes (tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation) in each model. It should be noted that the axes of rotation were different between the generic and subject-specific models. Thus, the simulation outputs were rotations about different axes of rotation.

To enable direct comparison between rotation angles about different axes of rotation, homogeneous transformation matrices were defined relative to a single coordinate system and joint angles were derived from these matrices. Here, the coordinate system was termed the ‘global coordinate system’, as it was equivalently defined across the generic model, the subject-specific model, and the dual-fluoroscopy results. The global coordinate system, which was derived from the subject-specific bone geometry of the tibia, was defined such that the superior-inferior axis (y axis) of the tibia was defined as the long axis of a cylinder fit to the tibia shaft. The anterior-posterior axis (x axis) was defined as the cross product of the superior-inferior axis and a temporary axis that represented the long axis of a cylinder fit to the tibia plafond surface. The medial-lateral axis (z axis) was defined as the cross product of the anterior-posterior and superior-inferior axes. Thus, dorsiflexion-plantarflexion, inversion-eversion, and internal-external rotation were represented by rotations about the medial-lateral, anterior-posterior, and superior-inferior axes, respectively. Tibiotalar joint angles were defined as roll-pitch-yaw angles (ZYX rotations) derived from the homogeneous transformation matrix describing the position of the talus relative to the tibia. Subtalar joint angles were similarly defined using the homogeneous transformation matrix describing the position of the calcaneus relative to the talus. Importantly, for the generic and subject-specific models, these homogeneous transformation matrices were defined based on the inverse kinematic results, meaning that these matrices incorporated the rotations about the modeled axes of rotation. Note that decomposing a rotation about any of the modeled joint axes results in rotations in each anatomical plane because the modeled joint axes of rotation were not aligned with the anatomical planes.

To define a reference standard, tibiotalar and subtalar joint angles were calculated using only the dual-fluoroscopy data. Using an approach that is equivalent to the joint angle definition described above for the inverse kinematic models, tibiotalar and subtalar joint angles were defined as roll-pitch-yaw angles (ZYX rotations) derived from homogeneous transformation matrices defined relative to the global coordinate system. Specifically, tibiotalar joint angles were derived from the homogeneous transformation matrix describing the position of the talus relative to the tibia and subtalar joint angles were derived from the homogeneous transformation matrix describing the position of the calcaneus relative to the talus. For further details regarding the definitions of the homogeneous transformation matrices, refer to Wang et al.37 and Roach et al.29

All joint angles were normalized to percent stance. Here, 0% stance corresponded to heel-strike, defined as the data frame with the minimum height position of the heel-marker following a downward trajectory, and 100% stance corresponded to toe-off, defined as the data frame with the minimum height position of the toe-marker prior to its upward trajectory.

Evaluating Modeled Axes of Rotation by Examining Axis Skew

To understand the tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation in the generic and subject-specific models, the angle between the tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation within each model was calculated. This angle quantifies axis skew, and is approximately 60° in the healthy ankle.26 A skew angle of 90° indicates that the two axes of rotation represented a typical universal joint (i.e., rotation about one axis is independent of rotation about the other axis). In contrast, skew angles that differ from 90° indicates that there is some synchronized motion between the two joints. This angle is considered to be functionally important, as axis skew facilitates the rolling of the foot during stance.10 For these reasons, axis skew was quantified and compared between the two models.

Analyzing Differences in Axes of Rotation

To evaluate differences between the generic and subject-specific axes of rotation, spherical statistics were implemented.8 Spherical statistics, also known as directional statistics, enables the statistical comparison of unit vectors by characterizing their spatial distribution. The analysis herein specifically tested the null hypothesis that the orientations and locations of the tibiotalar and subtalar axes in the generic and subject-specific models were not different. Differences in orientations were evaluated using the test for a common median direction of two samples of unit vectors.8 Differences in locations were evaluated using paired two-tailed Student's t-tests. A significance level of p<0.05 was used for all tests. In addition to significant differences, the mean (± standard deviation) differences in the orientations and locations of the tibiotalar and subtalar axes of the generic and subject-specific models were reported.

Analyzing Differences in Joint Angles

To evaluate to what extent the generic and subject-specific models predict in vivo tibiotalar and subtalar joint angles measured using dual-fluoroscopy, joint angles derived from the inverse kinematic simulations were compared to those measured using dual-fluoroscopy. Specifically, the average (± standard deviation) tibiotalar and subtalar joint angles were plotted versus normalized stance for the generic model, subject-specific model, and dual-fluoroscopy results, and these joint angles were directly compared. Modeled joint angles were considered to be in agreement with the dual-fluoroscopy results if the average was within one standard deviation of the dual-fluoroscopy results. It should be noted that stance and swing phases of gait were not analyzed separately because the dual-fluoroscopy data was limited to the transition phases of gait. Separate trials were acquired for heel-strike to early stance and late stance to toe-off because of the limited field of view of the fluoroscopes. As each collected trial was variable in length, averages were reported whenever data from at least 5 subjects were available. This means that the data at heel-strike and toe-off incorporated data from all 10 subjects, while data at the ends of the reported motions represented fewer subjects. The root mean square (RMS) error between the joint angles predicted by the models and those measured by dual-fluoroscopy were also quantified. A two-sided equivalence test for paired data (α=0.05) tested whether the RMS errors of the generic and subject-specific models were equivalent (i.e., did not demonstrate consistently larger or smaller errors as compared to the reference standard).27 In this test, equivalence is demonstrated if the 95 percent confidence interval of the paired mean differences is wholly between the upper and lower bounds of the margin of equivalence. The margin of equivalence was set at ±5°, as this is greater than the joint angle error that can be assessed with a goniometer.30

To examine the predictive accuracy of the models on a per-subject basis, a regression-based Bland-Altman analysis was performed.4 Here, joint angles of individual subjects were analyzed by calculating the bias, which represents the mean joint angle error, and the 95 percent limits of agreement, which represents 1.96 times the standard deviation of the joint angle errors. A regression approach described by Bland and Altman4 was used to define the bias and limits of agreement, as the mean and standard deviation of the joint angle errors were not constant. Using similar reasoning to the definition of the margin of equivalence and given that the limits of agreement represent the expected range of 95 percent of future measurements, limits of agreement greater than 5° were considered unacceptable.

Results

Skew Angle within the Generic & Subject-Specific Models

The skew angle describing the relative orientation between the axes at the tibiotalar and subtalar joints was larger in the generic model than in the subject-specific models (Table 1). In the generic model, the skew angle was 72.2°. In comparison, the skew angle in the subject-specific models (average ± standard deviation) was 65.3° ± 4.5° (range 57.9° to 71.4°).

Table 1. Orientation of Axes of Rotation in the Generic and Subject-Specific Models.

| Model1 | Tibiotalar Axis of Rotation2 |

Subtalar Axis of Rotation2 |

Skew Angle3 | Angle Between Generic & Subject-Specific Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | Tibiotalar Axis | Subtalar Axis | ||

| Generic | 0.979 | -0.105 | -0.174 | -0.121 | 0.787 | 0.605 | 72.2° | --- | --- |

| SubjSp 1 | 0.993 | 0.011 | -0.120 | -0.449 | 0.863 | 0.233 | 62.3° | 7.4° | 29.1 ° |

| SubjSp 2 | 0.979 | -0.092 | 0.179 | -0.489 | 0.860 | 0.146 | 57.9° | 20.4° | 34.4 ° |

| SubjSp 3 | 0.995 | 0.019 | -0.094 | -0.457 | 0.855 | 0.244 | 62.5° | 8.5 ° | 28.8 ° |

| SubjSp 4 | 0.999 | -0.013 | -0.017 | -0.468 | 0.802 | 0.372 | 61.0° | 10.5 ° | 24.1 ° |

| SubjSp 5 | 0.992 | 0.098 | -0.081 | -0.450 | 0.709 | 0.543 | 65.2° | 12.9 ° | 19.8 ° |

| SubjSp 6 | 0.996 | 0.090 | 0.002 | -0.399 | 0.859 | 0.322 | 71.4° | 15.1 ° | 23.2 ° |

| SubjSp 7 | 0.987 | 0.075 | -0.141 | -0.451 | 0.806 | 0.384 | 64.0° | 10.5 ° | 22.9 ° |

| SubjSp 8 | 0.999 | 0.014 | -0.004 | -0.355 | 0.789 | 0.501 | 69.8° | 12.0 ° | 14.7 ° |

| SubjSp 9 | 0.997 | 0.067 | -0.046 | -0.388 | 0.899 | 0.204 | 70.4° | 12.3 ° | 28.6 ° |

| SubjSp 10 | 0.986 | -0.053 | 0.156 | -0.428 | 0.700 | 0.572 | 68.3° | 19.2 ° | 18.5 ° |

| Mean ± St. Dev.4 | 0.999 | 0.022 | -0.017 | -0.439 | 0.825 | 0.357 | 65.3° ± 4.5° | 12.9° ± 4.3° | 24.4° ± 5.9° |

Subject-specific models are denoted by SubjSp.

Axis orientations are represented as unit vectors relative to the medial-lateral (x), anterior-posterior (y), and proximal-distal (z) planes; positive x, y, and z respectively defined as lateral, anterior, and proximal.

Skew angle was defined as the angle between the tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation calculated using the dot product.

Mean subject-specific axes of rotation were calculated based on methods reported by Fischer.8 Mean and standard deviation angles are also reported for the subject-specific models.

Axes of Rotation in the Generic versus Subject-Specific Models

Based on the spherical statistics analysis, the orientation and location of the axes of rotation in the subject-specific and generic models were significantly (p<0.05) different (Fig. 2). At the tibiotalar joint, the average angle (± standard deviation) between the generic and subject-specific axes was 12.9° ± 4.3° (range 7.4° to 20.4°). The mean tibiotalar axis in the subject-specific models was oriented in a lateral-posterior to medial-anterior direction, while that of the generic model was oriented in a lateral-anterior to medial-posterior direction (Table 1, sign of y component of tibiotalar axis differed between the generic and subject-specific models indicating a change in anterior-posterior orientation). Also, when compared to the generic model, the location of the subject-specific tibiotalar axis shifted significantly in the anterior (p < 0.01) and distal directions (p < 0.01) (Table 2). At the subtalar joint, the average angle (± standard deviation) between the generic and subject-specific axes was 24.4° ± 5.9° (range 14.7° to 34.4°). The orientation of the mean subject-specific subtalar axis had larger components in the medial-lateral and anterior-posterior direction than the generic model (Table 1, compare magnitude of x and y components of the generic and subject-specific subtalar axes). Also, when compared to the generic model, the location of the subject-specific subtalar axis was shifted significantly in the medial (p = 0.04), anterior (p = 0.02), and distal (p < 0.01) directions (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Axes of rotation at the (A) tibiotalar and (B) subtalar joints for the generic (green) and subject-specific (blue) models. To highlight the differences in axis orientation (top) all axes are aligned relative to a single representative talus. To highlight the differences in axis location (bottom), origin points are displayed relative to a representative tibia. Origins have been scaled so that depicted differences reflect differences in origin location, and not differences in the size of each subject. Arrows indicate location of axes of rotation in the generic model.

Table 2. Location of Axes of Rotation in the Generic and Subject-Specific Models (mm)1.

| Model2 | Tibiotalar Axis of Rotation3 |

Subtalar Axis of Rotation3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | |

| Generic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | -0.15 | -0.56 |

| SubjSp 1 | -0.25 | 0.81 | -1.07 | -0.34 | 0.04 | -1.63 |

| SubjSp 2 | 0.27 | 1.06 | -0.63 | 0.01 | 0.57 | -0.82 |

| SubjSp 3 | -0.34 | 0.81 | -1.45 | -0.38 | -0.10 | -1.80 |

| SubjSp 4 | 0.00 | 0.64 | -0.01 | 0.30 | -0.04 | -0.69 |

| SubjSp 5 | 0.02 | 0.51 | -1.46 | -0.07 | -0.01 | -2.20 |

| SubjSp 6 | -0.60 | 0.40 | -1.12 | -0.55 | -0.51 | -1.61 |

| SubjSp 7 | 0.16 | 0.58 | -0.22 | 0.14 | 0.22 | -0.84 |

| SubjSp 8 | -0.16 | 0.71 | -1.31 | -0.19 | 0.40 | -2.00 |

| SubjSp 9 | -0.21 | 0.92 | -1.25 | -0.21 | 0.19 | -1.67 |

| SubjSp 10 | 0.16 | 1.19 | -0.93 | 0.03 | 0.49 | -1.62 |

| Mean ± St. Dev4 | -0.09 ± 0.27 | 0.76 ± 0.25 | -0.95 ± 0.50 | -0.13 ± 0.26 | 0.12 ± 0.32 | -1.49 ± 0.52 |

Origins have been scaled so that depicted differences reflect differences in origin location, and not differences in the size of each subject. Specifically, we utilized scale factors from the measurement-based scaling method6 to calculate the position each subject's axes of rotation on a 50th percentile model.

Subject-specific models are denoted by SubjSp.

Axis locations are represented as Cartesian coordinates with the origin at the center of the talus and positive x, y, and z respectively defined as lateral, anterior, and proximal.

Mean and standard deviations of the subject-specific models

Joint Angles Predicted by Inverse Kinematics versus Measured by Dual-Fluoroscopy

Despite significant differences in the modeled axes of rotation, the generic model predicted average joint angles that were very similar to those predicted by the subject-specific models (Fig. 3). Specifically, the average tibiotalar and subtalar joint angles estimated by the generic model were within one standard deviation of those estimated by the subject-specific models for the majority of recorded motion (Fig. 3, green lines within shaded blue region for all directions of motion, except portions of subtalar internal rotation).

Figure 3.

(A) Tibiotalar and (B) subtalar joint angles measured by dual-fluoroscopy (black) compared to those estimated by the generic (green) and subject-specific (blue) models. Solid lines represent average across subjects. Given that the length of trials varied across subjects, averages were calculated for any region for which data existed for at least 5 subjects. Shaded regions represent one standard deviation. All joint angles are plotted versus percentage of the stance phase of gait, where 0% represents heel-strike of the imaged foot and 100% represents toe-off of the imaged foot. Dorsiflexion, inversion, and internal rotation are defined as positive.

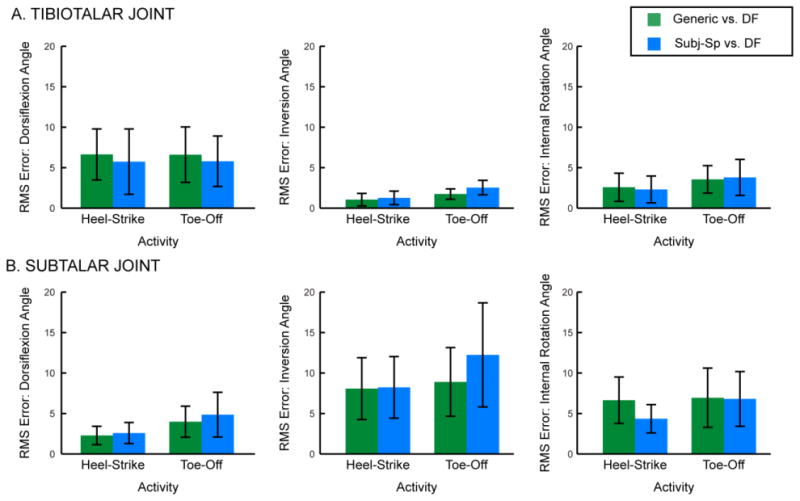

Based on analysis of RMS errors, neither model was consistently more accurate than the other (Fig. 4). In fact, the RMS errors of each model were statistically equivalent using a ±5° threshold (Fig. 5). Interestingly, both models represented in vivo tibiotalar joint motion more accurately than subtalar joint motion. During the majority of recorded stance, the average tibiotalar joint angles predicted by the models were within one standard deviation of those measured by dual-fluoroscopy (Fig. 3A). Here, the tibiotalar RMS errors (across subject average ± standard deviation) ranged from 0.6° ± 0.9° to 7.6° ± 7.5°, across all models and rotation directions (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the average subtalar joint angles predicted by the models were not within one standard deviation of those measured by dual-fluoroscopy during the majority of recorded stance (Fig. 3B). Here, the subtalar RMS errors (across subject average ± standard deviation) ranged from 1.1° ± 1.3° to 8.9° ± 12.2°, across all models and rotation directions (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Root mean square (RMS) error (in degrees) of the (A) tibiotalar and (B) subtalar joints during each activity. For each model, RMS errors were calculated between the joint angles estimated by the models versus measured experimentally using dual-fluoroscopy. The RMS errors are displayed separately for the generic (green) and subject-specific (blue) models. Bars represent average across subjects. Error bars represent one standard deviation, thereby illustrating across subject variability.

Figure 5.

Equivalence test of the RMS error for the generic and subject-specific models for the (A) tibiotalar and (B) subtalar joints. For each rotation direction (dorsiflexion, inversion, and internal rotation), the heel-strike (circles) and toe-off (squares) activities were analyzed separately. Filled shapes represent mean pairwise differences of RMS error in degrees. Solid horizontal lines represent 95 percent confidence intervals. The models have equivalent levels of RMS error for any condition in which the confidence intervals are within the ±5° margin of equivalence (vertical dotted lines).

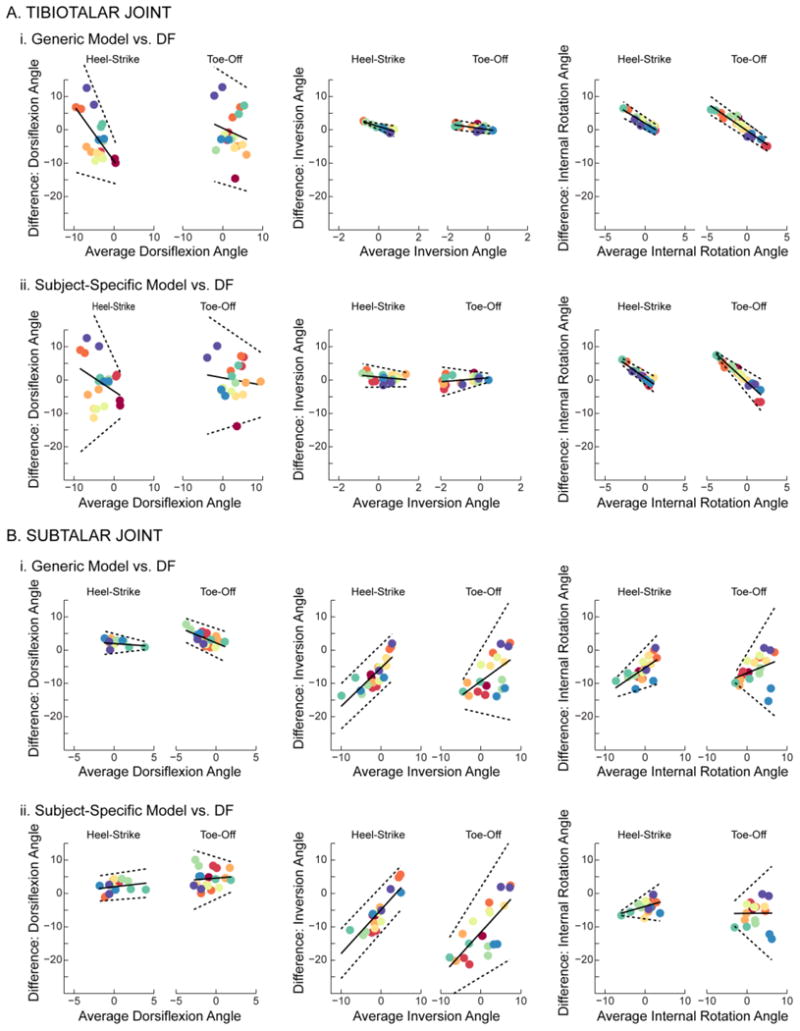

On a per-subject basis, neither model accurately predicted discrete tibiotalar or subtalar joint angles. The Bland-Altman analysis indicated that the error between the joint angles estimated by the models and those measured by dual-fluoroscopy exceeded 5° for 6 out of 10 subjects at the tibiotalar joint (Fig. 6A) and all 10 subjects at the subtalar joint (Fig. 6B). The largest errors were observed for tibiotalar dorsiflexion and subtalar inversion, as evidenced by the limits of agreement being largest for these rotation directions (Fig. 6). Interestingly, tibiotalar dorsiflexion and subtalar inversion respectively demonstrated negative and positive trends, suggesting that the accuracy of the models varied depending on the joint posture (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Regression-based Bland-Altman plots of (A) tibiotalar and (B) subtalar joint motion during the heel-strike and toe-off activities. Differences between motions predicted by the models versus measured experimentally using dual-fluoroscopy (DF) are displayed separately for the (i) generic and (ii) subject-specific models. Within each trial (unique points) and subject (unique colors), differences were calculated across all collected time points and then averaged. All calculated differences are model minus experimental, thus positive values represent an overestimation by the model. Solid lines represent mean difference (i.e., bias). Dotted lines represent 95% limits of agreement. Dorsiflexion, inversion, and internal rotation are defined as positive. It should be noted that the range of the x-axis varies across plots.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the axes of rotation in a generic versus a subject-specific model and evaluated whether incorporating subject-specific axes improved predictions of in vivo tibiotalar and subtalar motion. Although the orientation of the generic and subject-specific axes of rotation were significantly different, incorporating subject-specific axes of rotation based on talar morphology did not substantially improve predictions of tibiotalar or subtalar joint motion. Importantly, both models predicted average joint angles that were very similar. These joint angles did not agree well with those measured by dual-fluoroscopy, indicating that both models were unable to predict tibiotalar or subtalar joint angles on a per-subject basis. Given that the modeled axes of rotation influence the calculation of joint moments, muscle moment arms, and joint reaction forces, these inaccuracies could detrimentally affect the biomechanical analysis of gait. Our study highlights that the two kinematic models investigated may be inadequate for research studies aiming to discriminate tibiotalar and subtalar joint motion, and motivates research evaluating whether other modeling techniques can further improve calculations of tibiotalar and subtalar joint kinematics derived from skin-marker data. In future studies, more advanced methods to analyze joint kinematics (e.g. waveform analysis, principal component analysis) could be explored to further examine the accuracy of inverse kinematic solutions derived from skin-marker data and elucidate the interdependence of the three rotations defining tibiotalar and subtalar joint angles.

Different axes of rotation should result in different kinematic motion. Yet, minimal differences were observed between joint angles predicted by the generic and subject-specific models, despite significant differences in the orientations of the modeled axes of rotation. We interpret this finding to suggest that the relative orientation of the tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation may be more important than the individual orientation of either axis. This is in agreement with previous studies that have demonstrated that the skew angle, which quantifies the relative orientation between two axes of rotation, is a functionally important parameter in complex multi-degree-off-reedom joints, such as the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb,5 the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints of the wrist,22 and tibiotalar and subtalar joints of the ankle.26 This functional importance results from the interdependence of these joints' degrees-off-reedom during typical activities of daily living. For example, the interdependence of the tibiotalar and subtalar joints is responsible for sagittal plane motion during gait, which requires multi-degree-of-freedom rotations to roll the foot from heel-strike to toe-off. The skew angle of the generic and subject-specific models in our study were 72.2° and 65.3° ± 4.5°, respectively, which are larger than the previously reported 60° skew angle for the tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation.26 This difference in skew angle may have contributed to our finding that neither the generic nor subject-specific models were able to fully replicate in vivo motion of the tibiotalar and subtalar joints. Differences in the skew angle reported in our study and those reported in previous studies may indicate that our sample of 10 asymptomatic controls do not fully represent the variability of talar morphology in the population. A previous study examining 46 cadaveric ankles10 reports a range of skew angles from 41° to 75°, while the range in this study was 57.9° to 72.2°. Given that the prior study derived axes of rotation from cadaveric ankle joint motion,10 the differences in skew angle could also indicate that the method implemented in our study based on talar morphology results in axes of rotation with larger skew angles than methods based on ankle joint motion. This indicates that some aspects of joint kinematics are not captured by bone morphology.

Our results suggest that for studies that define the ankle to include only tibiotalar motion, a generic model with a rigid-foot may be sufficient for estimating joint motion. Thus, use of a generic ankle model in standard gait studies, which examine the position of the foot relative to the shank, is supported by our study. However, for studies interested in discriminating tibiotalar and subtalar joint motion, a more robust model will be necessary. Specifically, the limits of agreement calculated in our study indicate errors as large as 10° when estimating tibiotalar and subtalar joint angles for individual subjects. Given that 10° represents nearly 15% of plantarflexion/dorsiflexion range of motion and 20% of inversion/eversion range of motion, such errors would likely be unacceptable for studies aiming to compare what may be subtle inter-group differences in articulation of the tibiotalar and subtalar joint motion as well as those studies that aim to quantify joint articulation on a per-subject basis (e.g. to assist with diagnosis and treatment planning of individual patients). Collectively, our results suggest that more complex models may be necessary to obtain accurate predictions from inverse kinematic models. For example, models that utilize more than two degrees-of-freedom to represent the tibiotalar and subtalar joints may provide a more accurate representation of in vivo ankle motion. This recommendation is supported by previous studies that have demonstrated that both the tibiotalar and subtalar joints provide complex six-degree-of-freedom motion.7,29,33 However, defining these additional degrees-of-freedom may require new subject-specific approaches, as our previous work has demonstrated that a generic model with three degrees-of-freedom at both the tibiotalar and subtalar joints does not improve predictive accuracy.23 Alternatively, incorporating a multi-segment foot model may be necessary to accurately discriminate between tibiotalar and subtalar joint motion. This recommendation is supported by previous studies that have concluded a rigid-foot model cannot precisely capture motion of individual foot and ankle bones because the forefoot and midfoot violate the rigid-body assumption.21,34 Although we did not evaluate a multi-segment foot model in this study, our results for the rigid-foot model are still relevant as biomechanists routinely employ this simplified model. Future work could evaluate the accuracy of a multi-segment foot model using dual-fluoroscopy.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate whether implementation of subject-specific axes of rotation improves the accuracy of inverse kinematic predictions of in vivo tibiotalar and subtalar joint motion. However, we evaluated only one subject-specific modeling approach, which utilized talar morphology to define the tibiotalar and subtalar axes of rotation. This approach assumes that joint motion is influenced by bone morphology. Although this is a logical assumption, the extent to which joint morphology guides motion is open for debate, as other physiological factors such as neural control, muscle activation, and ligament laxity also contribute to joint motion. The importance of each of these factors may also vary with gait phase. For example, joint morphology may play a more critical role during weight-bearing, while soft tissue constraints and neuromuscular control may be more important during swing. Further research that separately examines the swing and stance phases of gait is necessary to elucidate the role of these physiological factors. Another limitation of our subject-specific modeling assumption is that it does not account for moving instantaneous axes of rotation, which have been demonstrated to exist at the tibiotalar and subtalar joints.13,32 Future work to refine this geometry-based approach could utilize both the proximal and distal joint surfaces (instead of the surfaces from a single bone), implement different axes of rotation for weight-bearing versus non-weight-bearing activities, incorporate muscle and ligament forces, and/or account for moving axes of rotation. Such refinements may provide more accurate kinematic representations. Alternatively, other methods for defining subject-specific axes of rotation or utilizing combinations of methods may be more appropriate for replicating in vivo tibiotalar and subtalar motion. Specifically, in this study, we did not evaluate functional approaches, optimization approaches, or helical axis approaches for defining subject-specific axes of rotation. In theory, given that each method for defining subject-specific axes of rotation is limited by measurement error, axes of rotation that represent the average axis derived from multiple methods may be more accurate than axes derived from any one method. Future studies that explicitly compare axes of rotation derived from talar morphology to those derived using other methods are necessary to fully evaluate the strengths and limitations of these methods. Such studies may also be able to elucidate the contributions of joint morphology versus other physiological factors to kinematic motion.

In summary, this study underscores that inverse kinematic simulations that utilize only skin-marker data and subject-specific axes of rotation derived from talar morphology are unable to replicate tibiotalar and subtalar joint motion measured in vivo using dual-fluoroscopy. Understanding the limitations of a given subject-specific model is critical for improving methods for defining subject-specific parameters and elucidating the model complexity required to obtain accurate predictions from inverse kinematics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R21 AR063844, S10 RR026565, F32 AR067075), the LS-Peery Discovery Program in Musculoskeletal Restoration, the American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society, and the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation with funding from the Orthopaedic Research Society. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of these funding sources. We thank K. Bo Foreman, Justine Goebel, Ashley Kapron, Bibo Wang, and Austin West for assistance collecting and processing the experimental data. We also thank Greg Stoddard for feedback regarding our statistical analyses as well as Glen Litchwark and Tim Dorn for their open-source OpenSim toolboxes, which were adapted to facilitate batch processing of our computer simulations.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The corresponding author and co-authors do not have a conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, that would inappropriately influence or bias the research reported herein.

References

- 1.Arnold EM, Ward SR, Lieber RL, Delp SL. A model of the lower limb for analysis of human movement. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:269–279. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9852-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beimers L, Tuijthof GJ, Blankevoort L, Jonges R, Maas M, van Dijk CN. In-vivo range of motion of the subtalar joint using computed tomography. J Biomech. 2008;41:1390–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bey MJ, Zauel R, Brock SK, Tashman S. Validation of a new model-based tracking technique for measuring three-dimensional, in vivo glenohumeral joint kinematics. J Biomech Eng. 2006;128:604–609. doi: 10.1115/1.2206199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8:135–160. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang LY, Pollard NS. Method for determining kinematic parameters of the in vivo thumb carpometacarpal joint. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2008;55:1897–1906. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2008.919854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delp SL, Anderson FC, Arnold AS, Loan P, Habib A, John CT, Guendelman E, Thelen DG. Opensim: Open-source software to create and analyze dynamic simulations of movement. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54:1940–1950. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.901024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engsberg JR. A biomechanical analysis of the talocalcaneal joint--in vitro. J Biomech. 1987;20:429–442. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher NI, Lewis TL, Embleton BJJ. Statistical analysis of sphereical data. Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge; 1989. Analysis of two or more samples of vectoral or axial data; pp. 194–229. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inman VT. The joints of the ankle. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isman RE, Inman VT. Anthropometric studies of the human foot and ankle. Bulletin of Prosthetics Research. 1969 Spring;:97–129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jennings Sphere fit (least squares) [Accessed February 22, 2016];2013 Available at: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/34129-sphere-fit--least-squared-

- 12.Kadaba MP, Ramakrishnan HK, Wootten ME. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1990;8:383–392. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leardini A, O'Connor JJ, Catani F, Giannini S. A geometric model of the human ankle joint. J Biomech. 1999;32:585–591. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leardini A, Stagni R, O'Connor JJ. Mobility of the subtalar joint in the intact ankle complex. J Biomech. 2001;34:805–809. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis GS, Cohen TL, Seisler AR, Kirby KA, Sheehan FT, Piazza SJ. In vivo tests of an improved method for functional location of the subtalar joint axis. J Biomech. 2009;42:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis GS, Piazza SJ, Sommer IHJ. In vitro assessment of a motion-based optimization method for locating the talocrural and subtalar joint axes. J Biomech Eng. 2006;128:596–603. doi: 10.1115/1.2205866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunberg A, Svensson OK. The axes of rotation of the talocalcaneal and talonavicular joints. The Foot. 1993;3:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maas SA, Ellis BJ, Ateshian GA, Weiss JA. Febio: Finite elements for biomechanics. J Biomech Eng. 2012;134:011005. doi: 10.1115/1.4005694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manter JT. Movements of the subtalar and transverse tarsal joints. The Anatomical Record. 1941;80:397–410. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nester C. Review of literature on the axis of rotation at the subtalar joint. The Foot. 1998;8:111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nester C, Jones RK, Liu A, Howard D, Lundberg A, Arndt A, Lundgren P, Stacoff A, Wolf P. Foot kinematics during walking measured using bone and surface mounted markers. J Biomech. 2007;40:3412–3423. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols JA, Bednar MS, Havey RM, Murray WM. Decoupling the wrist: A cadaveric experiment examining wrist kinematics following midcarpal fusion and scaphoid excision. J Appl Biomech. 2016:1–29. doi: 10.1123/jab.2015-0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichols JA, Roach KE, Fiorentino NM, Anderson AE. Predicting tibiotalar and subtalar joint angles from skin-marker data with dual-fluoroscopy as a reference standard. Gait Posture. 2016;49:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nozaki S, Watanabe K, Katayose M. Three-dimensional analysis of talar trochlea morphology: Implications for subject-specific kinematics of the talocrural joint. Clin Anat. 2016;29:1066–1074. doi: 10.1002/ca.22785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oatis CA. Biomechanics of the foot and ankle under static conditions. Phys Ther. 1988;68:1815–1821. doi: 10.1093/ptj/68.12.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parr WC, Chatterjee HJ, Soligo C. Calculating the axes of rotation for the subtalar and talocrural joints using 3d bone reconstructions. J Biomech. 2012;45:1103–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Group C. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: An extension of the consort statement. JAMA. 2006;295:1152–1160. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinbolt JA, Schutte JF, Fregly BJ, Koh BI, Haftka RT, George AD, Mitchell KH. Determination of patient-specific multi-joint kinematic models through two-level optimization. J Biomech. 2005;38:621–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roach KE, Wang B, Kapron AL, Fiorentino NM, Saltzman CL, Bo Foreman K, Anderson AE. In vivo kinematics of the tibiotalar and subtalar joints in asymptomatic subjects: A high-speed dual fluoroscopy study. J Biomech Eng. 2016;138 doi: 10.1115/1.4034263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rome K, Cowieson F. A reliability study of the universal goniometer, fluid goniometer, and electrogoniometer for the measurement of ankle dorsiflexion. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:28–32. doi: 10.1177/107110079601700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz MH, Rozumalski A. A new method for estimating joint parameters from motion data. J Biomech. 2005;38:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehan FT, Seisler AR, Siegel KL. In vivo talocrural and subtalar kinematics: A non-invasive 3d dynamic mri study. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:323–335. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siegler S, Chen J, Schneck CD. The three-dimensional kinematics and flexibility characteristics of the human ankle and subtalar joints--part i: Kinematics. J Biomech Eng. 1988;110:364–373. doi: 10.1115/1.3108455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tulchin K, Orendurff M, Karol L. A comparison of multi-segment foot kinematics during level overground and treadmill walking. Gait Posture. 2010;31:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tumer N, Blankevoort L, van de Giessen M, Terra MP, de Jong PA, Weinans H, Tuijthof GJ, Zadpoor AA. Bone shape difference between control and osteochondral defect groups of the ankle joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24:2108–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van den Bogert AJ, Smith GD, Nigg BM. In vivo determination of the anatomical axes of the ankle joint complex: An optimization approach. J Biomech. 1994;27:1477–1488. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang B, Roach KE, Kapron AL, Fiorentino NM, Saltzman C, Singer M, Anderson AE. Accuracy and feasibility of high-speed dual fluoroscopy and model-based tracking to measure in vivo ankle arthrokinematics. Gait & Posture. 2015;41:888–893. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]