Abstract

Purpose

We know little about whether it matters which oncologist a breast cancer patient sees with regard to receipt of chemotherapy. We examined oncologists’ influence on use of recurrence score (RS) testing and chemotherapy in the community.

Methods

We identified 7,810 women with stages 0-II breast cancer treated in 2013–15 through the SEER registries of Georgia and Los Angeles County. Surveys were sent 2 months post-surgery, (70% response rate, n=5,080). Patients identified their oncologists (n=504) of whom 304 responded to surveys (60%). We conducted multi-level analyses on patients with ER positive HER2 negative invasive disease (N=2973) to examine oncologists’ influence on variation in RS testing and chemotherapy receipt, using patient and oncologist survey responses merged to SEER data.

Results

Half of patients (52.8%) received RS testing and 27.7% chemotherapy. One-third (35.9%) of oncologists treated >50 new breast cancer patients annually; mean years in practice was 15.8. Oncologists explained 17% of the variation in RS testing but little of the variation in chemotherapy receipt (3%) controlling for clinical factors. Patients seeing an oncologist who was one standard deviation above the mean use of RS testing had over two-times higher odds of receiving RS (2.47, 95% CI 1.47–4.15), but a parallel estimate of the association of oncologist with the odds of receiving chemotherapy was much smaller (1.39, CI 1.03–1.88).

Conclusions

Clinical algorithms have markedly reduced variation in chemotherapy use across oncologists. Oncologists’ large influence on variation in RS use suggests that they variably seek tumor profiling to inform treatment decisions.

Keywords: Breast cancer, oncologist, chemotherapy, recurrence score assay

Introduction

Oncologists direct systemic treatment for breast cancer and thus exert powerful influence on patients’ receipt of specific regimens.[1] Over 90% of patients with early-stage disease are treated by the first oncologist they see[2] and 90% of them report that their oncologists advised them to omit or commit to systemic chemotherapy.[3] Treatment recommendations are informed by clinical guidelines, oncologist experience, and patient preferences. Clinical guidelines for adjuvant chemotherapy of patients with curable breast cancer have become increasingly dominant as algorithms have become more precise and evidence-based.[4]

Virtually nothing is known about whether it matters which oncologist a patient with early-stage breast cancer sees with regard to whether or not she receives adjuvant chemotherapy. On the one hand, advances in the precision of treatment guidelines might decrease variability of treatment across oncologists among patients with the same clinical presentation. On the other hand, several factors may engender substantial oncologist-driven variability in the community: First, evidence of chemotherapy’s benefit in specific clinical subgroups remains uncertain pending results of several clinical trials.[5] Second, oncologists may interpret guideline recommendations differently, especially in patients with favorable-prognosis early-stage breast cancer for whom the net benefit of chemotherapy may be very small but harms are substantial. Third, there may be differences in how oncologists negotiate treatment decisions with patients. In particular, patients’ desire to avoid or to receive chemotherapy may have greater influence on certain oncologists’ testing strategy and ultimately their recommendations.

The question of oncologists’ influence on variation in chemotherapy receipt is important for patients. Very little variation attributed to individual oncologists would suggest that patients seen in a variety of settings would receive similar treatment information and advice. On the other hand, very large variation attributed to individual oncologists might motivate a search for explanations and for patients to seek a second opinion.[2] However, no study has been published that examines the influence of oncologists on variations in receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy in the community. To address these questions, we surveyed a large, diverse contemporary sample of patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer and their attending oncologists to examine the influence of individual oncologists on the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Methods

Patient Sample and Data Collection

The iCanCare study identified women with early-stage breast cancer who were aged 20 to 79 years, diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive breast cancer, and reported to the Georgia or Los Angeles County Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry. Surveys were sent approximately 2 months after surgical treatment, between July 2013 and August 2015. Exclusions included: prior breast cancer, stage III/IV disease, or tumors >5 centimeters. Patients were mailed materials and a $20 cash gift. We used a modified Dillman method to encourage response (median time from diagnosis to survey completion, 6 months, SD 2.8).[6] We sent surveys to 7810 patients: 507 women were ineligible because they had exclusions noted above or were deceased, institutionalized or too ill to complete, or unable to complete a survey in Spanish or English. The survey was completed by 5,080 eligible patients (70%) and linked to SEER data and RS results.[3] The study protocol was approved by the University of Michigan, the University of Southern California, Emory University, and State Health Departments.

Oncologist sample and data collection

We identified attending oncologists through patient report. Most patients (81%) identified an attending oncologist. Surveys were sent to oncologists (N= 504) towards the end of the patient data collection period and 304 completed them (response rate 60%).

Merged sample

Among 2973 patients with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative invasive disease, 2517 were linked to 458 oncologists (see Supplemental Figure). Of these, 1621 were linked to the 281 responding oncologists. The number of respondent patients per oncologist ranged from 1 to 77 (with median 6).

Measures

The dependent variable was patient report of receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy. Patient clinical covariates were age, histologic grade, tumor size, nodal involvement, result of tumor testing with RS (not tested, low, intermediate, high) and selected comorbidities. We also included geographic location and diagnosis date because both variables have a substantial association with chemotherapy receipt. Oncologist variables included a unique oncologist identifier, annual volume of newly diagnosed breast cancer cases treated, years in practice, and teaching status (whether the practice had oncology fellows).

Statistical Analysis

We first described the distribution of patient and oncologist characteristics. The primary analysis was a multi-level logistic regression model with the oncologist identifier code defining the second level and the patient as the primary unit of observation. [7] We first regressed RS testing on selected patient covariates while accounting for a potential correlation in chemotherapy receipt among patients seeing the same oncologist. The base model included geographic location, date of diagnosis, and clinical variables that should be considered by oncologists in patients with invasive ER-positive, HER2-negative disease: age, comorbidities, histologic grade, tumor size, and nodal status. We also adjusted for the number of months between diagnosis and the survey as well as study site (Los Angeles County vs Georgia).

We then regressed receipt of chemotherapy on the patient covariates listed above and oncologist identifier; in this model we included RS results. We calculated oncologist-level variation in the base model for each regression, after adjusting for patient predictors. Both multilevel models incorporated survey design and non-response weights for patient as well as oncologist so that statistical inference was representative of our target population.[8] Finally, in both models we performed a secondary analysis included the sub-sample of patients linked to a responding, oncologist adjusted for patient information as in the base model and for the following oncologist-level predictors: years in practice, annual number of new breast cancer patients treated, and teaching status. Models were estimated using Proc GLIMMIX (SAS version 9.4).

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of patient (1a) and oncologist (1b) characteristics. The mean age of patients was 61.6. About one third (39.9%) were non-white; 15.0% had grade 3 disease; 79.9% had node-negative disease, 30.6% had one or more comorbidities, 52.8% received RS testing, and 27.7% initiated chemotherapy. One-third of oncologists (35.9%) treated more than 50 new breast cancer patients annually, the average years in practice was 15.8, and 19.4% had oncology fellows in their practices.

Table 1.

| a Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (n=2517) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % or Mean |

| Age at Time of Survey (years) | ||

| Mean age | 2517 | 61.6 |

| Age<50 | 380 | 15.1 |

| Age>50 | 2137 | 84.9 |

| Study Site | ||

| Georgia | 1455 | 57.8 |

| Los Angeles County | 1062 | 42.2 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1487 | 59.1 |

| Black | 383 | 15.2 |

| Hispanic | 403 | 16.0 |

| Asian | 195 | 7.7 |

| Other/Unknown/Missing | 49 | 1.9 |

| Tumor Grade | ||

| 1 | 905 | 36.0 |

| 2 | 1220 | 48.5 |

| 3 | 377 | 15.0 |

| Missing | 15 | 0.6 |

| Tumor Size (mm) | ||

| ≤10 | 788 | 31.3 |

| >10, ≤20 | 1140 | 45.3 |

| >20, ≤50 | 589 | 23.4 |

| Lymph Node Involvement (AJCC 7 Staging) | ||

| Node-negative (N0) | 2011 | 79.9 |

| Micrometastases (N1mi)* | 371 | 14.7 |

| Node-positive (N1) | 135 | 5.4 |

| Recurrence Score | ||

| Not tested | 1188 | 47.2 |

| Low Risk | 843 | 33.5 |

| Intermediate Risk | 364 | 14.5 |

| High Risk | 94 | 3.7 |

| Missing | 28 | 1.1 |

| Any comorbidities present | ||

| Yes | 1718 | 68.3 |

| No | 770 | 30.6 |

| Unknown | 29 | 1.2 |

| Received Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 1785 | 27.7 |

| No | 698 | 70.9 |

| Missing | 34 | 1.4 |

| b. Medical Oncologist Characteristics (n=304) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % or Mean |

| Study Site | ||

| Georgia | 145 | 47.7 |

| Los Angeles County | 159 | 52.3 |

| Teaching Status | ||

| Oncology fellowship | 59 | 19.4 |

| No Oncology fellowship | 237 | 80.0 |

| Missing | 8 | 2.6 |

| Number of new breast cancer patients in the last 12 months | ||

| <=20 | 64 | 21.1 |

| 21–50 | 108 | 35.5 |

| >50 | 109 | 35.9 |

| Missing | 23 | 7.6 |

| Years in practice | 298 | 15.8 |

N1mi is grouped with N0 for analyses, reflecting treatment algorithms in guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging

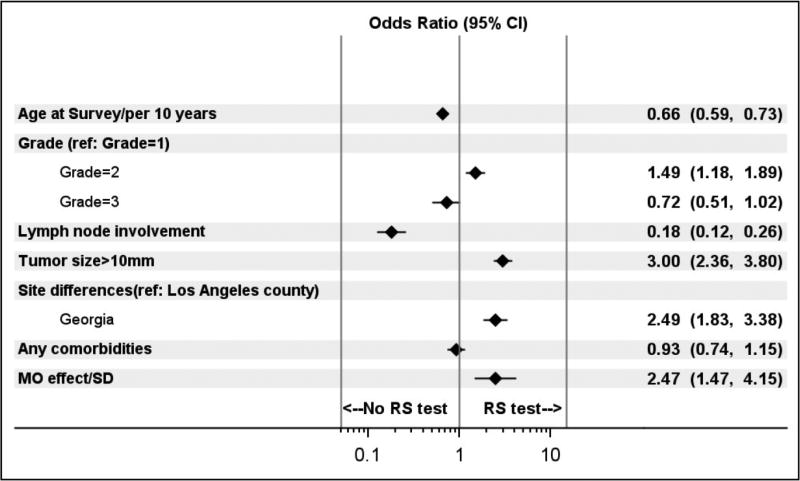

Figure 1 shows the results of the multi-level model regressing RS testing (yes/no) on patient factors and individual oncologist identifiers. Model 1 predicted receipt of RS well, with an area under the receiver-operator characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.84 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.82–0.86], and it explained 43% of the variability in RS receipt. Patient factors explained about 25% of the variability in RS receipt, and the oncologist identifier explained about 17% of this variability. The odds ratio (OR) for the oncologist effect (2.47, 95% CI 1.47, 4.15 indicates the amount by which a patient’s odds of receiving RS testing are multiplied if she sees an oncologist who is one standard deviation more likely to use chemotherapy than the average oncologist (or in other words, an oncologist in the 84th percentile instead of the 50th percentile for RS use). The other oncologist variables added little to the model: only years in practice significantly predicted RS use (OR per year 0.98, CI 0.96–0.99).

Figure 1.

Odds ratios (95% CI) for receipt of RS testing. This figure shows the estimated adjusted odds ratios for clinically pertinent patient factors and an attending oncologist identifier. The odds ratio listed for the oncologist effect represents the amount by which a patient’s odds of receiving RS testing are multiplied if she sees an oncologist with a propensity to use RS testing that is one standard deviation above the average oncologist’s (or in other words, an oncologist in the 84th percentile as opposed the 50th percentile for propensity to use RS).

Figure 2 shows results of the multi-level model that regressed receipt of chemotherapy on patient factors and an oncologist identifier. Model 1 predicted receipt of chemotherapy extremely well, with an AUC of 0.93 (CI 0.92–0.94) and it explained 67% of the variability in chemotherapy receipt. Patient factors explained about 64% of the variability in chemotherapy receipt and the oncologist identifier explained only about 3% of the variance. The OR for the oncologist effect (1.39, CI 1.03–1.88) indicates the amount by which a patient’s odds of receiving chemotherapy are multiplied if she sees an oncologist who is one standard deviation more likely to use chemotherapy than the average oncologist (or in other words, an oncologist in the 84th percentile instead of the 50th percentile for chemotherapy use). Again, of the additional oncologist factors considered, only years in practice significantly predicted chemotherapy use (OR per year 0.98, CI 0.96–0.99).

Figure 2.

Odds ratios (95% CI) for receipt of chemotherapy. This figure shows the estimated adjusted odds ratios including clinically pertinent patient factors and an attending oncologist identifier. The odds ratio listed for the oncologist effect represents the amount by which a patient’s odds of chemotherapy are multiplied if she sees an oncologist with a propensity to use chemotherapy that is one standard deviation above the average oncologist’s (or in other words, an oncologist in the 84th percentile as opposed the 50th percentile for propensity to use chemotherapy).

Discussion

Treatment of breast cancer is widely dispersed among oncologists in the community. Most oncologists treat some patients with breast cancer and there is wide variability in breast cancer specialization. It is important to know whether individual oncologists are responsible for substantial variation in chemotherapy use in community practice. In this study, we showed that the effect of individual oncologists on variation in adjuvant chemotherapy use was quite small relative to clinical factors. Patient clinical factors accounted for 64% of the variance in chemotherapy receipt for this community sample of early-stage breast cancer patients. By contrast, the individual oncologist accounted for only 3% of chemotherapy variance. The relatively small effect of oncologists on variation in chemotherapy use suggests a remarkably uniform approach to breast cancer treatment based on clinical factors. By contrast, we showed that clinical factors explain 25% of variation in RS testing and oncologist influence explained a substantial amount (17%) of variation in RS testing. Despite this variation in RS testing the ultimate decisions about chemotherapy use do not seem to vary much across oncologists after considering clinical factors.

Strengths of the study include a large, diverse, contemporary sample of patients who were linked to their attending oncologists through patient report. Limitations include decay in the sample due to non-response of patients or oncologists and geographic site limited to Georgia and Los Angeles County.

Our findings suggest that it matters little whom you see with regard to the likelihood of receiving chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. This underscores the marked advances in precision medicine for this disease. Clinical algorithms today are based largely on genomic testing and delimited pathological information such as sentinel node assessment.[4] A number of studies suggest that oncologists’ adherence to guidelines is high and disparities in treatment for patients with early-stage disease have dissipated.[3,9] Furthermore, there have been advances in standardizing the processing and reporting of tumor biology testing (e.g., ER and HER2), and RS testing (which itself provides standardized information on ER and HER2 expression) is from a sole-source laboratory.[10–14] Finally, the approach to pathology evaluation based on sentinel nodes has become much more uniform, including the collection and processing of specimens.[15] Taken together, these advances appear to have markedly limited individual oncologists’ influence on variation in chemotherapy use in the community. These findings should reassure patients because they suggest that oncologists are uniformly applying, evidence-based clinical algorithms to guide breast cancer treatment decisions.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure legend: Study flow diagram

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements and Funding Information

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health under award number P01CA163233 to the University of Michigan. The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003862-04/DP003862; the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000140C awarded to the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California (USC), and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute. The collection of cancer incidence data in Georgia was supported by contract HHSN261201300015I, Task Order HHSN26100006 from the NCI and cooperative agreement 5NU58DP003875-04-00 from the CDC. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

We acknowledge the work of our project staff (Mackenzie Crawford, M.P.H. and Kiyana Perrino, M.P.H. from the Georgia Cancer Registry; Jennifer Zelaya, Pamela Lee, Maria Gaeta, Virginia Parker, B.A. and Renee Bickerstaff-Magee from USC; Rebecca Morrison, M.P.H., Alexandra Jeanpierre, M.P.H., Stefanie Goodell, B.S., Paul Abrahamse, M.A., and Rose Juhasz, Ph.D. from the University of Michigan).

We acknowledge with gratitude our survey respondents.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest: none

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study through their return of a completed survey.

References

- 1.Li Y, Kurian AW, Bondarenko I, Taylor JM, Jagsi R, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ, Hofer TP. The influence of 21-gene recurrence score assay on chemotherapy use in a population-based sample of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161(3):587–595. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurian AW, Friese CR, Bondarenko I, et al. Second opinions from medical oncologists for early-stage breast cancer: Prevalence, correlates, and consequences. JAMA Oncology. 2017;3(3):391–397. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friese CR, Li Y, Bondarenko I, Hofer TP, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Deapen D, Kurian AW, Katz SJ. Chemotherapy decisions and patient experience with the recurrence score assay for early-stage breast cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(1):43–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R, Blair SL, Burstein HJ, Cyr A, Elias AD, Farrar WB, Forero A, Giordano SH, Goetz M, Goldstein LJ, Hudis CA, Isakoff SJ, Marcom PK, Mayer IA, McCormick B, Moran M, Patel SA, Pierce LJ, Reed EC, Salerno KE, Schwartzberg LS, Smith KL, Smith ML, Soliman H, Somlo G, Telli M, Ward JH, Shead DA, Kumar R. Invasive Breast Cancer Version 1.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2016;14(3):324–354. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, Pritchard KI, Albain KS, Hayes DF, Geyer CEJ, Dees EC, Perez EA, Olson JAJ, Zujewski J, Lively T, Badve SS, Saphner TJ, Wagner LI, Whelan TJ, Ellis MJ, Paik S, Wood WC, Ravdin P, Keane MM, Gomez Moreno HL, Reddy PS, Goggins TF, Mayer IA, Brufsky AM, Toppmeyer DL, Kaklamani VG, Atkins JN, Berenberg JL, Sledge GW. Prospective Validation of a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(21):2005–2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillman D, Smyth J, Christian L. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 3. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skrondal A, Rabe-Hesketh S. Generalized latent variable modeling: Multilevel, longitudinal and structural equation models. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfeffermann D, Skinner CJ, Holmes DJ, Goldstein H, Rasbash J. Weighting for unequal selection probabilities in multilevel models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 1998;60(1):23–40. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster JA, Abdolrasulnia M, Doroodchi H, McClure J, Casebeer L. Practice patterns and guideline adherence of medical oncologists in managing patients with early breast cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2009;7(7):697–706. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Schwartz KL, Zhao W, Abrahamse PH, Thomas DG, Jorns JM, Jewell R, Saber MES, Haque R, Katz SJ. Discordance between original and central laboratories in ER and HER2 results in a diverse, population-based sample. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2017;161(2):375–384. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, Martino S, Kaufman PA, Lingle WL, Flynn PJ, Ingle JN, Visscher D, Jenkins RB. HER2 testing by local, central, and reference laboratories in specimens from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 intergroup adjuvant trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(19):3032–3038. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.03.4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paik S, Bryant J, Tan-Chiu E, Romond E, Hiller W, Park K, Brown A, Yothers G, Anderson S, Smith R, Wickerham DL, Wolmark N. Real-world performance of HER2 testing--National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project experience. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94(11):852–854. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.11.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy JC, Reimann JD, Anderson SM, Klein PM. Concordance between central and local laboratory HER2 testing from a community-based clinical study. Clinical breast cancer. 2006;7(2):153–157. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman PA, Bloom KJ, Burris H, Gralow JR, Mayer M, Pegram M, Rugo HS, Swain SM, Yardley DA, Chau M, Lalla D, Yoo B, Brammer MG, Vogel CL. Assessing the 14 discordance rate between local and central HER2 testing in women with locally determined HER2-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(17):2657–2664. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chatterjee A, Serniak N, Czerniecki BJ. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: a work in progress. Cancer journal (Sudbury, Mass) 2015;21(1):7–10. doi: 10.1097/ppo.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure legend: Study flow diagram