Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether psychostimulants used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are associated with risk of adverse placental-associated pregnancy outcomes including preeclampsia, placental abruption, growth restriction, and preterm birth.

Methods

We designed a population-based cohort study where we examined a cohort of pregnant women and their liveborn infants enrolled in Medicaid from 2000 to 2010. Women who received amphetamine–dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate monotherapy in the first half of pregnancy were compared to unexposed women. We considered atomoxetine, a non-stimulant ADHD medication, as a negative control exposure. To assess whether the risk period extended to the latter half of pregnancy, women who continued stimulant monotherapy after 20 weeks were compared to those who discontinued. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated with propensity score stratification to control for confounders.

Results

Pregnancies exposed to amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (n=3331), methylphenidate (n=1515), and atomoxetine (n=453) monotherapy in early pregnancy were compared to 1,461,493 unexposed pregnancies. Among unexposed women, the risks of the outcomes were 3.7% for preeclampsia, 1.4% for placental abruption, 2.9% for small for gestational age, and 11.2% for preterm birth. The adjusted RR for stimulant use was 1.29 for preeclampsia (95% CI 1.11–1.49), 1.13 for placental abruption (0.88–1.44), 0.91 for small for gestational age (SGA; 0.77–1.07) and 1.06 for preterm birth (0.97–1.16). Compared to discontinuation (n=3527), the adjusted RR for continuation of stimulant use in the latter half of pregnancy (n=1319) was 1.26 for preeclampsia (0.94–1.67), 1.08 for placental abruption (0.67–1.74), 1.37 for SGA (0.97–1.93), and 1.30 for preterm birth (1.10–1.55). Atomoxetine was not associated with the outcomes studied.

Conclusion

Psychostimulant use during pregnancy was associated with a small increased relative risk of preeclampsia and preterm birth. The absolute increases in risks are small and thus, women with significant ADHD should not be counseled to suspend their ADHD treatment based on these findings.

Introduction

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses and stimulant prescriptions have markedly increased over the past two decades in women of childbearing age, resulting in increased stimulant exposure during pregnancy.1–3 Despite increasing use, there are limited safety data on stimulant use in pregnancy. While discontinuing treatment may be a viable option for some, women with severe symptoms may benefit from continued use of stimulants during pregnancy since severe, untreated ADHD can result in anxiety and aggressive behaviors that can disrupt family relationships and newborn care.4 Thus, understanding the safety of ADHD medications is critical for appropriate patient counseling regarding stimulant use during pregnancy.

The safety of first-line ADHD medications (e.g., amphetamine/ dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate) is of concern, as these stimulants cause vasoconstriction, which may impair placental perfusion.5 Impaired uteroplacental perfusion has been linked to obstetrical complications including preeclampsia, placental abruption, and fetal growth restriction6, as well as preterm birth.7

Our objective was to evaluate whether stimulant use in pregnancy is associated with increased risks of preeclampsia, placental abruption, small for gestational age birth (SGA), and preterm delivery. We also aimed to determine whether stimulant versus non-stimulant treatments for ADHD have different safety profiles with respect to placental complications and to define the etiologically-relevant exposure period for any observed increase in risk. We hypothesized that use of stimulants may adversely affect placentation (early pregnancy) or placental function (later pregnancy) leading to different manifestations of ischemic placental disease including impaired fetal growth, preeclampsia, placental abruption, and preterm birth.

Materials and Methods

We designed a population-based cohort study within the large, diverse population of low-income pregnant women covered by Medicaid (public insurance) in the United States. We linked pregnant women and their live born offspring within the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) database from 2000 to 2010. MAX data are managed by the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC) at the University of Minnesota. This mother-baby cohort has been described in detail previously8 and has been extensively used to study drug safety during pregnancy.9–14 The cohort includes deliveries in mothers ages 12–55 from 46 states and Washington D.C. For this study, we included women who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid from three months prior to the first day of their last menstrual period (LMP) until one month following delivery, without supplemental insurance or restricted benefits. Infants were also required to be enrolled or have a claim in the month after birth, unless they died. We excluded pregnancies where the infant was diagnosed with a major congenital anomaly (3.4%), as we were interested in whether stimulants increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes related to placental complications in pregnancies without congenital malformations.

Our early exposure window of interest was defined as the first 20 weeks of pregnancy (LMP to LMP+140 days). We chose this window as we hypothesized that exposure during this period could affect placental implantation and early development leading to the placental complications of interest. We focused on the most common stimulants, amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate. They have similar psychostimulant effects and side effects including insomnia and anorexia; however, the effects of amphetamine/dextroamphetamine are longer lasting.15 Atomoxetine is a non-stimulant ADHD medication used in cases where other stimulants are ineffective or need to be avoided due to side effects or potential for abuse.16 We included it in our study as a negative control exposure to evaluate the possibility of residual confounding by indication. We defined monotherapy based on at least one filled prescription from LMP to LMP+140 days with no prescription for any other ADHD medication from LMP-90 days to LMP+140 days. Our reference group for the early exposure window consisted of women without a prescription for any ADHD medication (amphetamine, amphetamine/dextroamphetamine, dextroamphetamine, methamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, methyphenidate, dexmethylphenidate, pemoline, atomoxetine, guanfacine, and clonidine) during the three months prior to pregnancy or LMP+140 days.

Because very few women newly initiated stimulant treatment late in pregnancy, we compared women who continued stimulant (amphetamine/dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate) treatment after LMP+140 to those who discontinued to evaluate whether the etiologically relevant risk period extends into the second half of pregnancy. The number of women exposed to atomoxetine in late pregnancy was too small to allow for a similar analysis. We defined continuation of stimulant monotherapy as filling at least one prescription for the same medication in the second half of pregnancy. We assessed late exposures from 141 until 245 days (>20 to 35 weeks) of pregnancy to avoid differential opportunity for exposure in preterm versus term births.

Preeclampsia was defined by an inpatient diagnosis from 141 days after LMP to 30 days following delivery. A prior validation study showed the positive predictive value (PPV) of this outcome definition to be 95%.17 Other outcome definitions were validated in a subset of study participants that received obstetrical care at Brigham and Women’s Hospital or Massachusetts General Hospital (International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 2017 abstract, in press). Placental abruption was defined by at least one diagnosis during the delivery hospitalization (PPV 92%). Small for gestational age (SGA) was defined by a diagnosis in maternal or infant claims from delivery to 30 days after delivery (PPV 84%). Preterm birth was defined by diagnosis and procedure codes that were present in maternal or infant claims from delivery to 60 days following delivery (PPV 78%). The International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) codes used to identify the outcomes are presented in Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

We considered risk factors for ischemic placental disease and preterm birth including demographic characteristics (age, race, geographic region, year, multiparity), maternal and pregnancy characteristics (multifetal gestation, alcohol use, tobacco use, other drug abuse or dependence, obesity/overweight), and certain chronic conditions (inflammatory, cardiovascular, renal) as potential confounders. Additionally, we also adjusted for indications for stimulants and proxies for indication severity, other psychiatric and pain conditions, proxies for healthcare utilization intensity, and co-treatment with psychiatric and pain medication. Confounders were defined based on ICD-9 codes or prescriptions dispensed from LMP-90 days to LMP+140 days. Healthcare utilization variables were assessed during the period prior to pregnancy (LMP-90 to LMP-1) to capture the usage due to preexisting health conditions, which may serve as a proxy for general health prior to pregnancy. The following potential indications for psychostimulant treatment were defined as one or more relevant ICD-9 codes from LMP-90 days to delivery to enhance sensitivity: ADHD, migraine, bipolar, chronic fatigue syndrome, narcolepsy, and epilepsy. We assumed that these chronic conditions temporally preceded the use of stimulants, though they may have been captured after the prescription claim was identified.

We estimated risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using log-binomial regression. We controlled for potential confounding using propensity scores. Propensity score models predict the likelihood of exposure, based on the measured confounders. This enables the comparison of subjects who had a similar probability of receiving the treatment. Thus, propensity score methods allow us to mimic a randomized trial where comparable subjects are randomly assigned to treatment or control, assuming there are no unmeasured confounders. The propensity score model included exposed vs. reference as the dependent variable and confounders as independent variables: demographic characteristics, pregnancy characteristics, and chronic inflammatory, cardiovascular, and renal conditions (24 covariates), potential indications and proxies for the indication severity and healthcare utilization (35 covariates; see eTable 2 for complete list).

After we estimated the propensity scores using logistic regression, we trimmed the non-overlapping regions of the exposed and reference group distributions and then used a fine stratification approach which has been shown to control for confounding better or more efficiently than matching or coarse stratification when exposures are rare.18 Exposed subjects were stratified into 50 equally-sized strata. Then reference subjects in each stratum were weighted according the distribution of the exposed subjects.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to explore the robustness of our findings. To address the possibility that women with only one prescription may not truly be exposed in pregnancy, we modified the definition of exposed to require at least two filled prescriptions in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. Next, we redefined exposure as having drug supply available from 8–18 weeks gestation, the period during which extensive remodeling of the uterine spiral arteries occurs which is a process noted to be incomplete in ischemic placental disease.19 This time period may be particularly relevant if the mechanism whereby stimulants affect these outcomes is interference with early placental development. We also stratified the exposed according to days’ supply available during the first 140 days of pregnancy, grouped as <30, 30–60, 61–90, and >90 days; this was collapsed to <30, 30–60, and >60 days for atomoxetine due to limited sample size.

The study was approved by the institutional review board at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the need for informed consent was waived.

Results

The primary reference group was pregnant women who were not dispensed any ADHD medication from 90 days before LMP to 140 days after LMP (n=1,461,493). The exposed groups included women exposed to monotherapy of amphetamine/dextroamphetamine (n=3,331), methylphenidate (n=1,515), and atomoxetine (n=453) during the first 140 days of pregnancy (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). Women using ADHD medication monotherapy in pregnancy were on average younger, more likely to be white, and had more risk factors for placental-mediated pregnancy complications. Women who continued to use stimulant monotherapy after 20 weeks were more similar to women who discontinued use in the first 20 weeks, although they were older, more likely to be multiparous, and more likely to have a diagnosis of ADHD (Table 1). After propensity score weighting, comparison groups were similar with respect to the covariates of interest (Appendixes 3–6, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of exposed and unexposed subjects

| Characteristic | No Stimulant Use LMP-90 to LMP+140 (N=1,461,493) | Monotherapy LMP to LMP+140 (N=5,299) | Monotherapy Discontinuation LMP+140 (N=3,946) | Monotherapy Continuation >LMP+140 (N=1,353) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| N or Mean | % or SD | N or Mean | % or SD | N or Mean | % or SD | N or Mean | % or SD | |

| Age at delivery | ||||||||

| ≤ 19 | 351638 | 24.1 | 2134 | 40.3 | 1772 | 44.9 | 362 | 26.8 |

| 20–29 | 855235 | 58.5 | 2360 | 44.5 | 1650 | 41.8 | 710 | 52.5 |

| 30–39 | 235508 | 16.1 | 761 | 14.4 | 493 | 12.5 | 268 | 19.8 |

| ≥40 | 19112 | 1.3 | 44 | 0.8 | 31 | 0.8 | 13 | 1.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 581811 | 39.8 | 4181 | 78.9 | 3052 | 77.3 | 1129 | 83.4 |

| Black/African American | 491124 | 33.6 | 626 | 11.8 | 528 | 13.4 | 98 | 7.2 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 219666 | 15.0 | 127 | 2.4 | 96 | 2.4 | 31 | 2.3 |

| Other/unknown* | 168892 | 11.6 | 365 | 6.9 | 270 | 6.9 | 95 | 7.0 |

| Risk Factors for placental-complications | ||||||||

| Multiparous | 1104366 | 75.6 | 2919 | 55.1 | 2032 | 51.5 | 887 | 65.6 |

| Multifetal gestation | 41956 | 2.9 | 114 | 2.2 | 92 | 2.3 | 22 | 1.6 |

| Tobacco use | 52913 | 3.6 | 498 | 9.4 | 324 | 8.2 | 174 | 12.9 |

| Alcohol use | 8891 | 0.6 | 86 | 1.6 | 70 | 1.8 | 16 | 1.2 |

| Other drug abuse/dependence | 21991 | 1.5 | 254 | 4.8 | 193 | 4.9 | 61 | 4.5 |

| Asthma | 68321 | 4.7 | 501 | 9.5 | 381 | 9.7 | 120 | 8.9 |

| Hypertension | 38192 | 2.6 | 159 | 3.0 | 110 | 2.8 | 49 | 3.6 |

| Antihypertensive medication | 40598 | 2.8 | 294 | 5.6 | 205 | 5.2 | 89 | 6.6 |

| Diabetes | 25977 | 1.8 | 94 | 1.8 | 73 | 1.9 | 21 | 1.6 |

| Insulin use | 14638 | 1.0 | 54 | 1.0 | 39 | 1.0 | 15 | 1.1 |

| Antidiabetic medication | 11977 | 0.8 | 58 | 1.1 | 45 | 1.1 | 13 | 1.0 |

| Overweight or obese | 31329 | 2.1 | 150 | 2.8 | 115 | 2.9 | 35 | 2.6 |

| Potential Indications for Stimulants† | ||||||||

| ADHD | 10997 | 0.8 | 3070 | 57.9 | 2184 | 55.4 | 886 | 65.5 |

| Migraine | 165332 | 11.3 | 1023 | 19.3 | 743 | 18.8 | 280 | 20.7 |

| Bipolar disorder | 23901 | 1.6 | 895 | 16.9 | 666 | 16.9 | 229 | 16.9 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 56547 | 3.9 | 452 | 8.5 | 334 | 8.5 | 118 | 8.7 |

| Narcolepsy | 193 | 0.0 | 42 | 0.8 | 27 | 0.7 | 15 | 1.1 |

| Epilepsy | 17023 | 1.2 | 155 | 2.9 | 117 | 3.0 | 38 | 2.8 |

| Other Psychiatric Conditions | ||||||||

| Depression | 96814 | 6.6 | 1596 | 30.1 | 1184 | 30.0 | 412 | 30.5 |

| Adjustment disorder | 17340 | 1.2 | 233 | 4.4 | 187 | 4.7 | 46 | 3.4 |

| Anxiety disorder | 54289 | 3.7 | 975 | 18.4 | 672 | 17.0 | 303 | 22.4 |

| Sleep disorder | 10183 | 0.7 | 189 | 3.6 | 138 | 3.5 | 51 | 3.8 |

| Other Medication Use | ||||||||

| Atypical antipsychotic | 18080 | 1.2 | 876 | 16.5 | 686 | 17.4 | 190 | 14.0 |

| Antidepressant | 138074 | 9.5 | 2639 | 49.8 | 1959 | 49.7 | 680 | 50.3 |

| Benzodiazepine | 45483 | 3.1 | 1063 | 20.1 | 663 | 16.8 | 400 | 29.6 |

| Opioid | 323505 | 22.1 | 2140 | 40.4 | 1451 | 36.8 | 689 | 50.9 |

| Triptan | 16202 | 1.1 | 184 | 3.5 | 124 | 3.1 | 60 | 4.4 |

| NSAID | 244501 | 16.7 | 1290 | 24.3 | 911 | 23.1 | 379 | 28.0 |

| Acetaminophen | 389759 | 26.7 | 2240 | 42.3 | 1546 | 39.2 | 694 | 51.3 |

| Anticonvulsant or lithium | 18186 | 1.2 | 680 | 12.8 | 498 | 12.6 | 182 | 13.5 |

| Indication Severity Proxies | ||||||||

| Number of ADHD diagnoses | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Number of depression diagnoses | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.24 | 0.43 |

| Number of generic medications | 4.26 | 3.87 | 8.83 | 5.45 | 8.70 | 5.39 | 9.21 | 5.61 |

| Number of ED visits‡ | 0.28 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 1.17 | 0.46 | 1.14 | 0.57 | 1.27 |

| Number of hospitalizations‡ | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.25 |

| Number of outpatient visits‡ | 1.81 | 3.27 | 4.67 | 7.33 | 4.84 | 7.60 | 4.18 | 6.46 |

Monotherapy includes amphetamine/ dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate, and atomoxetine. Covariates were defined from LMP-90 to LMP+140, unless otherwise indicated. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ED, emergency department; LMP, last menstrual period; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SD, standard deviation.

Other race/ethnicity category includes Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, other, unknown

1 or more ICD-9 diagnostic codes from LMP-90 to delivery

Healthcare utilization proxy variables defined during LMP-90 to LMP-1

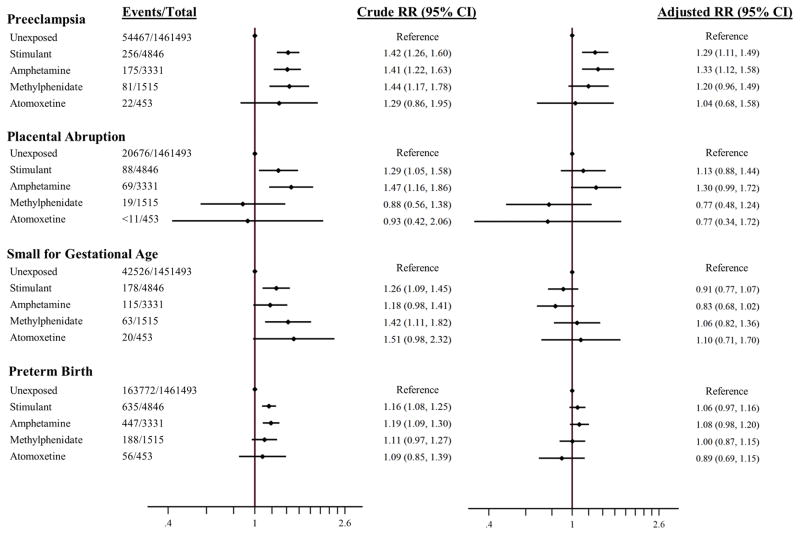

Among unexposed women, the risks of the outcomes were 3.7% for preeclampsia, 1.4% for placental abruption, 2.9% for small for gestational age, and 11.2% for preterm birth. In unadjusted analyses, women using amphetamine/dextroamphetamine monotherapy in the first half of pregnancy (irrespective of their exposure in the second half of pregnancy) had an increased risk of all placental-mediated complications examined. Women using methylphenidate had increased risks for all outcomes examined except for placental abruption. However, after adjusting for potential confounders, the associations were attenuated and suggested no effect for most exposure-outcome contrasts except for stimulant exposure as a class and preeclampsia (adjusted RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.11–1.49) and amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and preeclampsia (1.33, 1.12–1.58). Atomoxetine use was not associated with an increased risk for the outcomes in crude or adjusted analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relative risks for placental complications related to exposures during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. Stimulant includes amphetamine–dextroamphetamine- and methylphenidate-exposed. As per Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data use agreement, cell sizes <11 are not presented.

Continuing to use stimulant monotherapy (amphetamine/dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate) in the second half of pregnancy compared to discontinuation in the first half of pregnancy was also associated with an increased risk of preterm birth after adjusting for confounders (adjusted RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.10–1.95, Table 2).

Table 2.

Stimulant monotherapy continuation (n=1319) after 20 weeks versus discontinuation (n=3527)

| Outcome events, n (%)

|

RR (95% CI)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuation | Discontinuation | Crude | Adjusted* | |

| Preeclampsia | 75 (5.7%) | 181 (5.1%) | 1.11 (0.85 – 1.44) | 1.26 (0.94 – 1.67) |

| Placental abruption | 30 (2.3%) | 58 (1.6%) | 1.38 (0.90 – 2.14) | 1.08 (0.67 – 1.74) |

| Small for gestational age | 60 (4.5%) | 118 (3.3%) | 1.36 (1.00 – 1.85) | 1.37 (0.97 – 1.93) |

| Preterm birth | 222 (16.8%) | 413 (11.7%) | 1.42 (1.21 – 1.65) | 1.30 (1.10 – 1.55) |

Stimulant monotherapy includes amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate only

Adjusted RRs calculated with propensity score stratification

Sensitivity analyses

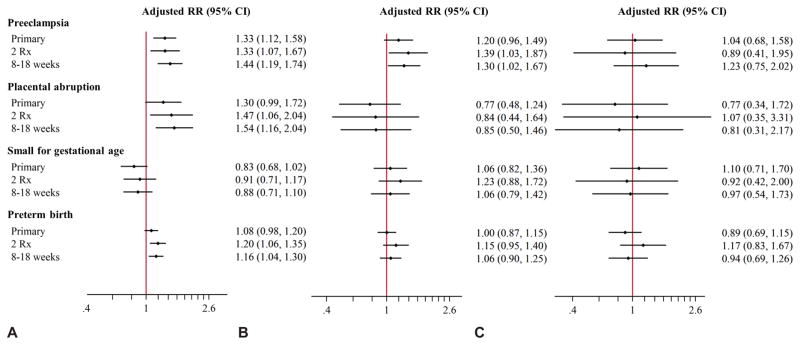

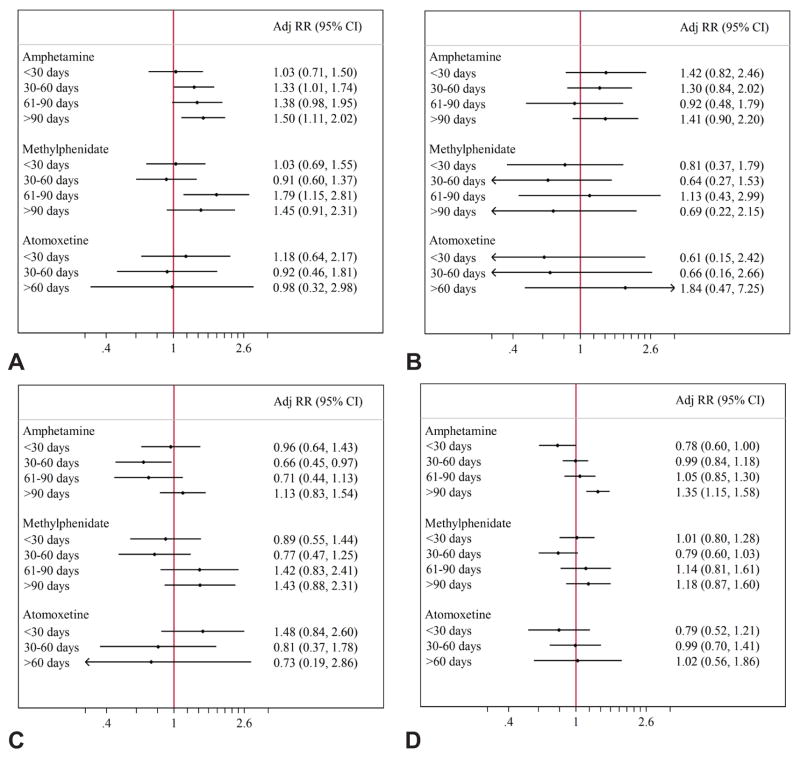

The positive associations identified in the primary analyses remained similar or slightly strengthened for women filling two or more prescriptions during the first half of pregnancy. Redefining exposure as using stimulants in a narrower time window surrounding placentation (8–18 weeks) also produced consistent findings. Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine use was associated with preeclampsia, placental abruption, and preterm birth, and methylphenidate use with preeclampsia in these sensitivity analyses. Atomoxetine remained unassociated with the outcomes studied (Figure 2). When we stratified the exposed subjects based on days-supply of medication in the first 140 days after LMP, the association between amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and preeclampsia was apparent for women who had at least a 30-day supply; adjusted RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.71–1.50) for <30 days, 1.33 (1.10–1.74) for 30–60 days, and 1.38 (0.98–1.95) for 61–90 days, and 1.50 (1.11–2.02) for >90 days; similar findings were not observed for placental abruption or preterm birth, where only >90 days of exposure to amphetamine/dextroamphetamine were associated with an increased risk of preterm birth. There was no evidence of a clear dose-response relationship for methylphenidate and either preeclampsia or SGA; only exposure >60 days was associated with increased risk of preeclampsia. There were no trends corresponding to dose of atomoxetine for any of the outcomes examined (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Primary and sensitivity exposure definitions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder monotherapy compared to unexposed reference group. Amphetamine–dextroamphetamine (A), methylphenidate (B), and atomoxetine (C). Redefining amphetamine–dextroamphetamine exposure based on two prescription fillings (n=2,007) and drug supply available at 8–18 weeks of gestation (n=2,589) compared to primary analysis based on one prescription filling (n=3,331). Redefining methlyphenidate exposure based on two prescription fillings (n=751) and drug supply available at 8–18 weeks of gestation (n=1,100) compared to primary analysis based on one prescription filling (n=1,515). Redefining atomoxetine exposure based on two prescription fillings (n=153) and drug supply available at 8–18 weeks of gestation (n=276) compared to primary analysis based on one prescription filling (n=453).

Figure 3.

Dose response investigation. Adjusted relative risks associated with the number of days covered during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy by prescriptions filled from 90 days before last menstrual period to 140 days after last menstrual period among women exposed to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder monotherapy. Preeclampsia (A), placental abruption (B), small for gestational age (C), and preterm birth (D).

Discussion

In a cohort of almost 1.5 million pregnancies, we identified over 5,000 pregnancies exposed to ADHD monotherapy. Stimulant monotherapy in the first half of pregnancy remained associated with a 1.3-fold increased risk of preeclampsia after controlling for confounding by indication and other risk factors. Continued stimulant exposure late in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of preterm birth (1.3-fold compared to discontinuation). The absolute increases in risk are small and may not justify additional surveillance of pregnancies exposed to psychostimulant therapy. Atomoxetine, a non-stimulant ADHD medication, was not associated with the adverse pregnancy outcomes examined.

We would expect stronger associations for amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate than for atomoxetine monotherapy. Amphetamine-type drugs (amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate) increase levels of circulating epinephrine through activation of the sympathetic nervous system producing vasoconstriction.20 Alternatively, atomoxetine acts as a selective norepinephrine transporter inhibitor primarily in the prefrontal cortex and effects on vasoconstriction are limited.21 Thus, atomoxetine may be an ideal negative control exposure due to the similar indication for use and pharmacological effects, but limited potential for side effects on the maternal vasculature. Experiments in sheep demonstrated that amphetamine causes vasoconstriction and decreased uteroplacental perfusion.5 Furthermore, if stimulants cause inadequate placental blood flow, exposure during the second half of pregnancy may be particularly relevant for growth restriction since most fetal weight gain occurs in late pregnancy.

Small studies that lacked control for confounders suggested an association between stimulant abuse and therapeutic use for weight control during pregnancy and lower birth weight (including SGA) and premature birth.22,23 A cohort study also identified an association between late pregnancy therapeutic methamphetamine use and fetal growth restriction.24 A recent cohort study compared women who used ADHD medication and women with ADHD diagnosis without medication to women with no ADHD diagnosis or medication in the general population of pregnancies in Denmark from 1997–2008.25 They reported that methylphenidate or atomoxetine use in pregnancy (n=186) was not associated with reduced birthweight or gestational age at birth. However, they reported that women with a hospital-based diagnosis of ADHD who did not use medication (n=275) were at an approximately 2-fold increased risk of preterm birth. This study highlighted the potential for cofounding by indication (i.e. ADHD) and the need for larger studies of amphetamine/dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, which are the most commonly used stimulants in the US.

Residual confounding is always a concern in observational studies. Due to prior research implicating depression and antidepressant use in the risk of preeclampsia and preterm birth,9,26 adjusting for depression and associated treatment were of key concern. While we defined potential indications, smoking, and overweight/obesity from ICD-9 codes, these may have been under recorded. However, because we controlled for many psychiatric and physical conditions and co-medication use which may be correlated with ADHD, smoking, and obesity, we likely controlled for these to a large extent by proxy. The negative findings for atomoxetine provide further reassurance in this regard.

Outcomes were defined by a set of validated algorithm-based definitions designed to maximize specificity while preserving sensitivity and should lead to unbiased estimates of the relative risks. SGA appeared to be under-recorded in these data, as the rate of 2.9% in the unexposed was lower than the expected rate of around 10%. It has been shown that if specificity is high and both sensitivity and specificity are non-differential, then risk ratios are unbiased.27 However, the lower PPV for some outcomes (e.g. SGA, preterm birth) may have biased results toward the null.

The modest effect estimates for early pregnancy exposure in this study may be a result of frequent discontinuation of stimulants early in the first half of pregnancy. Indeed, requiring two prescriptions or a day supply that overlapped the period from 8 to 18 gestational weeks resulted in somewhat stronger associations. Additional risk was also observed for women who continue to use stimulants in the second half of pregnancy, compared to discontinuation during the first half of pregnancy. Continuation of use reflects both a higher cumulative exposure and exposure at a different time compared to discontinuation. It therefore remains unclear whether later exposure or longer duration of treatment explains the increased risk of preterm birth, primarily associated with continuation of treatment in late pregnancy.

In conclusion, stimulant use was associated with increased risks of preeclampsia and preterm birth. Although the point estimates were elevated, associations for placental abruptions and SGA were not statistically significant. . However, the absolute increases in risks are small and thus, women with significant ADHD should not be counseled to suspend their ADHD treatment based on these findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH100216). Krista Huybrechts was supported by a career development grant K01MH099141 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Brian Bateman was supported by a career development grant K08HD075831 from the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development.

Footnotes

Presented as a poster at the 29th Annual Meeting of the Society for Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology in Miami, Florida on June 20–21, 2016 and the 33rd International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management in Montreal, Canada on August 26–30, 2017.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Financial Disclosure

Jacqueline M. Cohen has received salary support from a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline for unrelated work. Sonia Hernández-Díaz received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer for unrelated work; salary support from the North American AED Pregnancy Registry; and consulted for UCB, Teva, and Boehringer-Ingelheim; her institution received training grants from Pfizer, Takeda, Bayer, and Asisa. Brian Bateman received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Pacira, and Baxalta for unrelated work. Yoonyoung Park consulted for Optum for unrelated projects and was supported by Pharmacoepidemiology Program at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, partially funded by Pfizer, Takeda, Bayer, and Asisa. Rishi Desai reports receiving a research grant from Merck for unrelated work. Elisabetta Patorno reports receiving research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Boehringer-Ingelheim for unrelated work. Krista Huybrechts received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Boehringer-Ingelheim for unrelated work.

References

- 1.Renoux C, Shin JY, Dell’Aniello S, Fergusson E, Suissa S. Prescribing trends of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications in UK primary care, 1995–2015. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82:858–68. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haervig KB, Mortensen LH, Hansen AV, Strandberg-Larsen K. Use of ADHD medication during pregnancy from 1999 to 2010: a Danish register-based study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:526–33. doi: 10.1002/pds.3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louik C, Kerr S, Kelley KE, Mitchell AA. Increasing use of ADHD medications in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:218–20. doi: 10.1002/pds.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besag FM. ADHD treatment and pregnancy. Drug Saf. 2014;37:397–408. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stek AM, Baker RS, Fisher BK, Lang U, Clark KE. Fetal responses to maternal and fetal methamphetamine administration in sheep. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1995;173:1592–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Medically indicated preterm birth: recognizing the importance of the problem. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:53–67. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nijman TA, van Vliet EO, Benders MJ, Mol BW, Franx A, Nikkels PG, et al. Placental histology in spontaneous and indicated preterm birth: A case control study. Placenta. 2016;48:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmsten K, Huybrechts KF, Mogun H, Kowal MK, Williams PL, Michels KB, et al. Harnessing the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) to Evaluate Medications in Pregnancy: Design Considerations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmsten K, Huybrechts KF, Michels KB, Williams PL, Mogun H, Setoguchi S, et al. Antidepressant use and risk for preeclampsia. Epidemiology. 2013;24:682–91. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31829e0aaa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, Cohen LS, Holmes LB, Franklin JM, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2397–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai RJ, Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, Mogun H, Patorno E, Kaltenbach K, et al. Exposure to prescription opioid analgesics in utero and risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, Patorno E, Desai RJ, Mogun H, Dejene SZ, et al. Antipsychotic Use in Pregnancy and the Risk for Congenital Malformations. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:938–46. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bateman BT, Patorno E, Desai RJ, Seely EW, Mogun H, Dejene SZ, et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and the Risk of Congenital Malformations. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:174–84. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patorno E, Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, Cohen JM, Desai RJ, Mogun H, et al. Lithium Use in Pregnancy and the Risk of Cardiac Malformations. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2245–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pliszka SR, Browne RG, Olvera RL, Wynne SK. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Adderall and Methylphenidate in the Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:619–26. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, DuPaul G, Earls M, Feldman HM, et al. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1007–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmsten K, Huybrechts KF, Kowal MK, Mogun H, Hernandez-Diaz S. Validity of maternal and infant outcomes within nationwide Medicaid data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23:646–55. doi: 10.1002/pds.3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai RJ, Rothman KJ, Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF. A Propensity-score-based Fine Stratification Approach for Confounding Adjustment When Exposure Is Infrequent. Epidemiology. 2017;28:249–57. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pijnenborg R, Bland JM, Robertson WB, Brosens I. Uteroplacental arterial changes related to interstitial trophoblast migration in early human pregnancy. Placenta. 1983;4:397–413. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(83)80043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broadley KJ. The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;125:363–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bymaster FP, Katner JS, Nelson DL, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Threlkeld PG, Heiligenstein JH, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:699–711. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Debooy VD, Seshia MM, Tenenbein M, Casiro OG. Intravenous pentazocine and methylphenidate abuse during pregnancy. Maternal lifestyle and infant outcome. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:1062–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160340048012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naeye RL. Maternal use of dextroamphetamine and growth of the fetus. Pharmacology. 1983;26:117–20. doi: 10.1159/000137793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith LM, LaGasse LL, Derauf C, Grant P, Shah R, Arria A, et al. The infant development, environment, and lifestyle study: effects of prenatal methamphetamine exposure, polydrug exposure, and poverty on intrauterine growth. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1149–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bro SP, Kjaersgaard MI, Parner ET, Sorensen MJ, Olsen J, Bech BH, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes after exposure to methylphenidate or atomoxetine during pregnancy. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:139–47. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S72906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tak CR, Job KM, Schoen-Gentry K, Campbell SC, Carroll P, Costantine M, et al. The impact of exposure to antidepressant medications during pregnancy on neonatal outcomes: a review of retrospective database cohort studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:1055–69. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Copeland KT, Checkoway H, McMichael AJ, Holbrook RH. Bias due to misclassification in the estimation of relative risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1977;105:488–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.