Highlights

-

•

Radical vulvectomy is a very agressive surgery.

-

•

Deshiscence of vulvar wound is one of the most feared complications.

-

•

Negative wound pressure therapy could be incorporate in the management of this complications.

Abbreviation: NPWT, Negative pressure wound therapy

Keywords: Vulvar carcinoma, Negative pressure wound therapy, Lotus petal flap, Wound dehiscence, Vulvectomy

Abstract

Introduction

Vulvar cancer has a lower incidence in high income countries, but is rising, in part, due to the high life expectancy in these societies. Radical vulvectomy is still the standard treatment in initial stages. Wound dehiscence contitututes one of the most common postoperative complications.

Presentation of case

A 76 year old patient with a squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, FIGO staged, IIIb is presented. Radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection with lotus petal flaps reconstruction are performed as the first treatment. Wound infection and dehiscence of lotus petal flaps was seen postoperatively. Initial management consisted in antibiotics administration and removing necrotic tissue from surgical wound. After this initial treatment, negative wound pressure therapy was applied for 37 days with good results.

Discussion

Wound dehiscence in radical vulvectomy remains the most frequent complication in the treatment of vulvar cancer. The treatment of this complications is still challenging for most gynecologic oncologist surgeons.

Conclusion

The utilization of the negative wound pressure therapy could contribute to reduce hospitalization and the direct and indirect costs of these complications.

1. Introduction

Vulvar carcinoma accounts for about 5–8% of cancers of the female reproductive organs and 0.6% of all cancers in woman [1]. The incidence is increasing nowadays because rising life expectancy in developed societies [2]. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histological subtype and the average age is 65 [3].

The purpose of this article is to explain the possibility of using negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) as a treatment of flap dehiscence of surgical wound after a radical vulvectomy. This work has been done in line with the SCARE criteria [4].

2. Case report

A 76 years old woman came to our hospital with a 7 cm exofitic lesion in left labia. She had history of BMI of 33, high blood pressure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic venous insufficiency and deafness. She had hysterectomy and bilateral anexectomy surgery thirty years ago because of metrorrhagia. Vulvar biopsy showed squamous cell carcinoma. There were two clinically suspicious groin nodes at Magnetic Resonance Imagining so FIGO staging was IIIb. The treatment of this tumor staging is Radical vulvectomy with bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection plus adjuvant radiotherapy or radical radiotherapy if the pacient is not fit for surgery.

After preoperative studies, the patient performed in a radical vulvectomy with bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection and lotus petal flaps reconstruction.

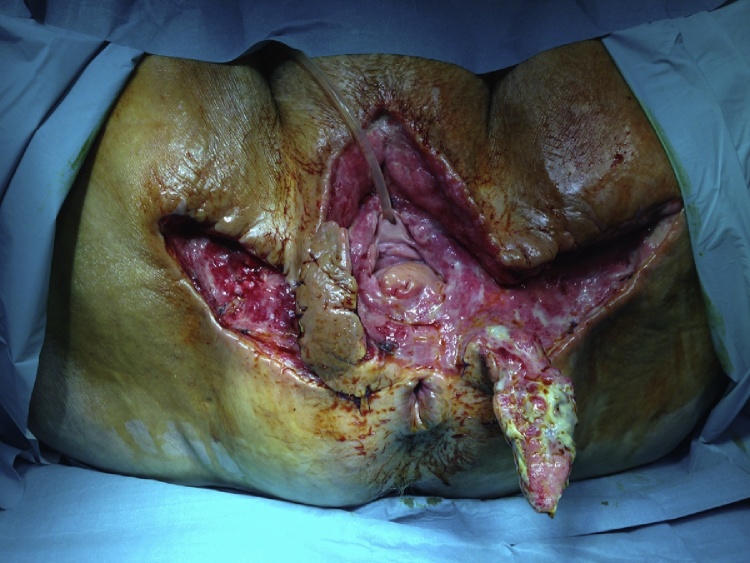

The surgery was successful but an infection appeared at the postoperative period causing the dehiscence of lotus petal flaps (Fig. 1). Bacterial culture was taken and intravenous antibiotic therapy was initiated and performed a wide debridement under sedation in operation room.

Fig. 1.

Infection and dehiscence of lotus petal flaps.

We initiate antibiotic treatment firstly with ciprofloxacin 500 mg each 8 h. The bacterial culture shows an infection with Pseudomona aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus faecalis and we changed to cefotaxime plus ampicilin because of intermedia resistence of the bacteria to ciprofloxacin (after 10 days of ciprofloxacin). When we repeat the culture it shows Escherichia coli yet so she left our unity with antibiotic treatment.

Daily dressing and washing and debridement was done to remove necrotic tissues. Vesical catheter, rectal pressure catheter with silicone balloon and parenteral nutrition was established to avoid the contamination of the surgical wound.

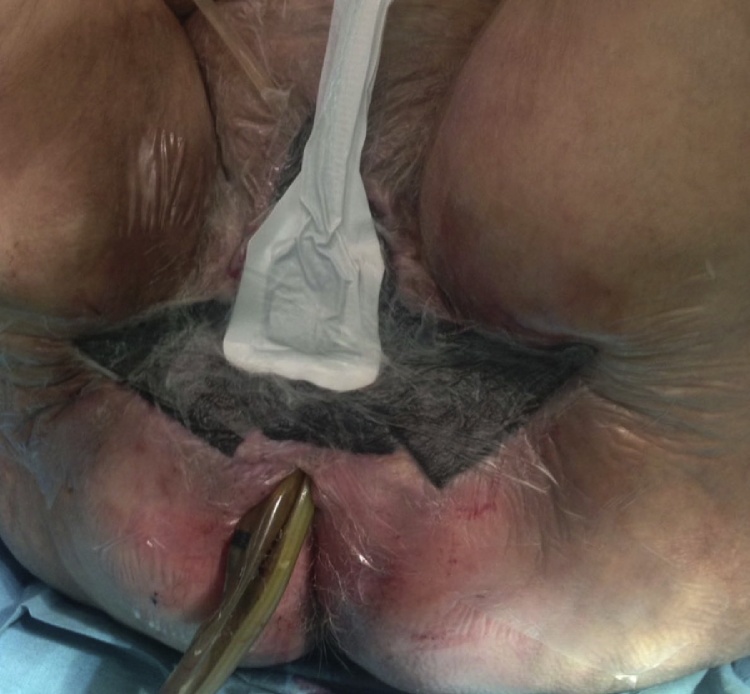

Due to failure of local care, NPWT was started eight days after the wide debridement to reduce bacterial rates and tension on wound edges (Fig. 2). The lotus petal flaps were taken down.

Fig. 2.

Negative pressure wound therapy applied on wound.

The procedure is described below and the NPWT system was changed twice a week.

-

-

Remove dressings.

-

-

Remove the polyurethane foam taking into account the number introduced in the last cure.

-

-

Washing of the wound with chlorhexidine brush.

-

-

We remove the debris and the inverted growing skin edge with Volkmann's curette.

-

-

Local disinfection for 15 min.

-

-

Polyester sheets coated with silver nanocrystalline (it is decided to apply according to the appearance of the wound).

-

-

Placement of new sponges and new dressings.

-

-

Connection to vacuum pump continue pressure 100 mmHg.

The surgical wound presented right evolution, the edges were getting closer and the patient was discharged from hospital with outpatient control. She was sent to a hospital for chronic illnesses after 37 days of NPWT. Finally, healing by second intention completed the process (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Healing by second intention completed.

Consent was obtained for the publication of the case report and the images from the patient.

3. Discussion

Due to the extension of the vulvar injury, the anatomical location and the mutilating procedure, vulvectomy has a lot of postoperative complications. Traditionally, vulvectomy has been aggressive surgery, and in our hospital before reconstruction of the lotus flap was established, dehiscence of surgical wound was about 80%. With this technique, this complication has decreased to 4% [5].

In our patient, bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy was performed using an open technique. Inguino-femoral lymphadenectomy is considered the main reason for the large percentage of wound healing disorders. Some authors have described an endoscopic technique to avoid wound complications [6]. Due to the warm and humid environment of the groin, dissection of the inguinal lymph nodes increases the risk of wound infection and also leads to the chronic development of lymphedema [7].

Negative pressure therapy is an advanced method of wound care, which uses negative pressure to close multiple lesions in different areas of the body. Negative pressure favours wound closure by different mechanisms, including removal of interstitial fluid, stimulation of angiogenesis and mitosis, decreased bacterial load, increased growth factors, and increased white blood cells and fibroblasts within the wound [8], [9].

It is indicated in acute, sub acute and chronic wounds in which it is necessary to stimulate the processes of tissue repair, such as granulation and epithelialization. Two of the indications are the reduction of wound size to achieve surgical closure or large wounds located in a place where it is difficult to seal satisfactorily with dressings. One of the contraindications of the use of this therapy is the existence of malignant neoplasia, but it is not our case, since the patient underwent surgery in which the margin of resection was greater than 2 cm.

We used silver coating as adjuvant for the antibiotic treatment, as it is described in some articles [7], [10]. The mechanisms of action of silver involve the inhibition of cellular respiration, the binding of nucleic acids and causing their denaturation and alteration of the permeability of the membranes of microbial cells.

NPWT leads outpatient control avoiding prolonged hospital stays and reducing the direct and indirect costs of these complications [9], [11].

4. Conclusion

Nowadays, despite having incorporated new intraoperative reconstructive techniques, the complication of suture dehiscence is present. The NPWT is a good method to resolve this process avoiding a second surgery, reducing hospital staying, costs and morbi-mortality that would result in this type of patients a new surgery.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work received financial support from de Medtronic University Chair for Training and Surgical Research. (University Jaume I (UJI), Castellon, Spain).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local ethics and research committee and followed the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Consent

Written informed consent was required for collecting data.

Authors contribution

Study concepts: Antoni Llueca

Study design: Antoni Llueca

Data acquisition: Anna Serra, Blanca Segarra,

Quality control of data and algorithms: Raquel del Moral

Data analysis and interpretation: Yasmin Maazouzi

Manuscript preparation: Antoni Llueca

Manuscript editing: Antoni Llueca, Dolors Piquer

Manuscript review: Anna Serra, Jose Luis Herraiz

Guarantor

Dr. Llueca is the guarantor of the paper.

References

- 1.Stehman F.B. Invasive cancer of the vulva. In: Di Saia P., Creasman W., editors. Clinical Gynecologic Oncology. 7th edn. St. Louis; Mosby: 2007. pp. 235–264. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green T.H. Carcinoma of the vulva. A reassessment. Obstet. Gynecol. 1978;52:462–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hacker N.F. Vulvar cancer. In: Berek J.S., Hacker N.F., editors. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic Oncology. 5th edn. Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2010. pp. 576–592. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herraiz J.L., Llueca A. Vulvar reconstruction in vulvar cancer: lotus petal suprafascial flap. Gynecol. Surg. 2016;13:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herraiz J.L., Llueca A., Maazouzi Y., Piquer D., Calpe E. Surgical technique for video endoscopic inguinal lymphadenectomy in vulvar cancer. Prog. Obstet. Ginecol. 2016;59(4):252–255. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanirowski P.J., Wnuk A., Cendrowski K., Sawicki W. Growth factors, silver dressings and obstetrics and gynecology: a review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015;292(4):757–775. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3709-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiménez C.E. Terapia de presión negativa: una nueva modalidad terapéutica en el manejo de heridas complejas, experiencia clínica con 87 casos y revisión de la literatura. Rev. Colomb. Cir. 2007;22(4):209–224. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller M.S. New microvascular blood flow research challenges practice protocols in negative pressure wound therapy. Wounds. 2005;17(10):290–294. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright Wound management in an era of increasing bacterial antibiotic resistance: a role for topical silver treatment. Am. J. Infect. Control. 1998;26(December (6)):572–577. doi: 10.1053/ic.1998.v26.a93527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raimond E. Use of negative pressure wound therapy after vulvar carcinoma: case studies. J. Wound Care. 2017;26(February (2)):72–74. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2017.26.2.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]