Abstract

The present study evaluated the activities of heart rate variability (HRV) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in response to the presentation of affective pictures correlated with posttraumatic growth (PTG) among adults exposed to the Tianjin explosion incident. The participants who were directly involved in the Tianjin explosions were divided into control, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and PTG group according to the scores of PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version and PTG Inventory survey. All participants received exposure to affective images. Electrocardiogram recording took place during the process for the purpose of analyzing HRV. Meanwhile, functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) was used to measure DLPFC activity through hemodynamic response. Our results indicated that, while performing the negative and positive picture stimulating, PTG increased both in low and high frequency components of HRV compared with the control group, but PTSD was not observed in this phenomenon. Moreover, the fNIRS data revealed that PTG had an increased activation in the left DLPFC compared to the control in the condition of negative pictures stimulating, wheras PTSD showed a higher activation in the right DLPFC while receiving positive pictures stimulating. To our knowledge, this is the first study which provides the differences between PTSD and PTG in emotional regulation.

Introduction

Life-threatening illnesses and events such as earthquakes, motor vehicle accidents or terror incidents may cause post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) and post-traumatic growth (PTG)1–5. PTG refers to the experience of positive change that occurs as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life crises, describing the experience of individuals who do not only recover from trauma, but also discover it as an opportunity for further individual development. Those individuals overcome trauma with improved psychological functioning in specific domains6. PTG has been reported by a significant number of people who have encountered major life challenges, resulting in such factors described as new possibilities, relating to others, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life7.

Traumatic events can cause a series of strong emotional responses, such as fear, anxiety and depression. Since the development of a new chapter in DSM-V on Trauma-and Stress–Related Disorders much more attention has been paid to the emotional symptoms that accompany PTSD8. Emotion regulation is defined as a process by which individuals modify their emotional experiences, expressions, and subsequent physiological responses9. Meanwhile, emotion regulation is recognized as a facet of coping which is central to trauma recovery and represents an important ability to manage, experience, and express intense negative feelings associated with traumatic events and thereby coping with trauma10. In this sense, emotion regulation to traumatic reminders equals a hallmark phenomenon during the post-traumatic experience, and the changes of emotion regulation which including the emotional experiences and expressions are central features of the long-term psychological consequences of traumatic events.

Many studies across both clinical and non-clinical research have provided evidence that emotion dysregulation is associated with PTSD across ethnically diverse samples. Nicole H. Weiss et al. declared that emotion dysregulation may contribute to the development, maintenance, and/or exacerbation of PTSD among substance use disorder patients with PTSD11. Natalie R. Stevens et al. found that child abuse exerted a direct effect on post-traumatic symptoms and indirect effects through difficulties with emotion regulation12. Ehring and Quack used questionnaires to assess characteristics of emotion regulation, showing that PTSD symptom severity was significantly associated with all variables assessing emotion regulation difficulties13. Furthermore, Matthew T. Tull et al. declared that PTSD symptom severity was found to be associated with lack of emotional acceptance, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Meanwhile, overall difficulties in emotion regulation were associated with PTSD symptom severity, controlling for negative affect14.

However, remarkably few studies examined the emotion regulation associated with PTG. Larsen and Berenbaum found that emotion expressive suppression positively predicted distress, but not PTG. However, bootstrapped mediation models showed that emotional processing has a significant indirect effect on PTG and distress through its effect on creating meaning15. Researchers examine the mediating effects of perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulation on the relationship between enacted stigma and PTG among HIV-affected children, and the results showed that emotional regulation together with hopefulness and perceived social support mediated the impact of enacted stigma on PTG16.

Heart rate variability

The emotion regulation that humans experience while interacting with the trauma is associated with a high degree of physiological arousal. Indeed, acute and chronic psychosocial stress not only increases heart rate but also significantly reduces heart rate variability (HRV) in humans17. The power spectrum of short-term time series contains two major components of high frequency (HF, 0.15–0.40 Hz) and low frequency (LF, 0.01–0.15 Hz). HF-HRV and LF-HRV reflecting parasympathetic (vagal) activity and baroreflex function respectively18,19. HRV is common across anxiety-related phenomena and have a relation with vagal tone, state, trait, and clinical forms of anxiety, and represents a reliable and important psychophysiological marker of emotion regulation capacity. Individuals with greater emotion regulation ability have been shown to have higher levels of HRV20. Moreover, the LH-HRV and HF-HRV components have different contribution during the emotion regulation processes. Comparing with LF-HRV component, the HF-HRV component is considered to play a much more important role in these processes. Specifically, HF-HRV will increase in the emotion regulation condition relative to simply an emotion-induced condition, which means a higher cognitive control ability and more activity of the parasympathetic nervous system in decreasing the emotion response21. Meanwhile, it has been proposed that LF-HRV play an important role in anxiety-related emotional control, high LF-HRV has been linked to higher anxiety level, and less emotional control ability22.

Some evidence in the literature revealed that LF-HRV and HF-HRV were most often reported lower in people with PTSD compared with healthy controls and trauma-exposed individuals without PTSD. The research by Wahbeh showed that LF-HRV and HF-HRV were lower in combat veterans than comparing no-PTSD with PTSD23. Moreover, Hauschildt et al. found that PTSD showed lower LF-HRV and HF-HRV than non-trauma-exposed controls at baseline and throughout different affective conditions24.

To our knowledge, however, there is no research on the relation of HRV and PTG.

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

Executive brain areas, especially the prefrontal cortex (PFC), exert an inhibitory influence on sub-cortical structures, such as the amygdala, allowing the organism to adaptively respond to demands from the environment, and organize their emotional and behavioral responses effectively. Thus, active cortical brain areas are indicative of greater inhibitory and emotion regulation20.

There is a growing body of literature which suggests that individual differences in HRV are related to PFC activity. In addition, it should be noted that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) may play a more important role because of its unique anatomy. HRV was associated with activity patterns in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), individuals with higher HRV showed both higher overall vmPFC blood-oxygen-level-dependent activity25. Sakreida et al. reported the effects in HRV by manipulating the cortical excitability of the DLPFC through neuro-navigated repetitive low frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS)26. DLPFC showed a higher positive co-variation between HF-HRV and regional cerebral blood flow27. Moreover, some research confirmed that the left and right DLPFC contribute differently to the LF and HF of HRV. Lane et al. declared that HF correlated with blood flow in the right DLPFC28, while LF is also affected more by DLPFC. Gonçalves applied tDCS over the left DLPFC and found a decrease in LF29.

DLPFC also has been proposed to be a central regulatory brain area in emotion processing. Although DLPFC has no direct anatomical connection to the amygdala, it regulates an emotion generated by amygdala, insula and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, therefore it might exert a more indirect control over areas of affect generation by its projections to the pre-supplementary motor area and anterior midcingulate cortex, which are both involved in emotion regulation and have an association to regulation success30.

Because of the important roles of DLPFC in HRV and emotion function, it becomes a region of interest which involved the pathophysiology of PTSD. Aupperle et al. used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine neural responses during anticipation of negative and positive emotional images in PTSD. They found that greater DLPFC activation was associated with lower PTSD symptom severity31. Similarly, a longitudinal neuroimaging study reported that greater DLPFC thickness was associated with greater post-traumatic stress disorder symptom reductions and better recovery32. Moreover, a clinical research study reported that PTSD patients who received 10 daily sessions of right dorsolateral prefrontal rTMS at a frequency of 10 Hz experienced greater therapeutic effects than with slow-frequency application or sham stimulation33. This implied that the DLPFC region is not only involved in PTSD, but might also correlate closely with psychological recovery, such as PTG, from a severely traumatic event in humans.

While there is a great deal of research focusing on neural correlations of PTSD, the research on PTG has received much less attention compared with PTSD, and the work on neural correlation with PTG is very scarce. As a result, PTG is an appealing but poorly understood construct. We used Google scholar and Pubmed to search for research on neural correlation of PTG, and found only two publications. Research by Rabe demonstrated that greater relative left baseline prefrontal activation measured by EEG alpha power corresponded with greater self-perceived PTG, as reflected in the post-traumatic growth inventory (PTGI) scale. Moreover, relative left fronto-central activity was associated with the PTGI dimensions of new possibilities, changed relationships, appreciation of life, and personal strength but not with spiritual changes34. A very recent fMRI study showed that the total scores on a PTGI were positively and significantly associated with the delta-regional grey matter volume in the right DLPFC, indicating that the DLPFC seems to be the main neural correlate of PTG35.

Therefore, we intended to explore the changes of HRV and the activation of the DLPFC accompanied emotion experience in PTG. We compared the characteristics of these correlated physiological and neural changes between PTG and PTSD. Our primary interests included: (1) Comparison of differences in HRV between PTG and PTSD while performing affective pictures; (2) Exploration whether hemoglobin concentration changes in the DLPFC modulated by affective pictures are different between PTG and PTSD. We hypothesize that the low and high frequency components of HRV in PTG may be higher while performing affective pictures, and there may be a differentiation of emotion function in DLPFC between PTG and PTSD.

Materials and Method

Participants

On Wednesday, 12 August 2015, a series of explosions that killed 165 people and injured hundreds of others occurred at a container storage station at the Port of Tianjin. Initially, for the purpose of investigating the HRV changes while performing affective picture stimulating among PTSD and PTG subjects, a sample of 90 participants was collected from central and surrounding areas affected very seriously by the explosions in Tianjin. Then, in order to explore the activation of the DLPFC, all participants were asked to receive fNIRS measurement through the same selection route. The basic information of the samples is presented in Table 1. All participants experienced the explosions within 3 kilometers.

Table 1.

Basic information of participants.

| Sample (n = 90) | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 53 | 58.89 |

| Female | 37 | 41.11 |

| Age (M ± SD) | 28.58 ± 6.52 | |

| Educational level | ||

| Less than high school | 8 | 8.89 |

| High school | 36 | 40.00 |

| More than high school | 46 | 51.11 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 51 | 56.67 |

| Other | 39 | 43.33 |

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All methods and protocols in the experiment were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the approved methods and protocols. The procedure of the study was fully explained to the participants, and informed written consent was obtained from each participant before the study.

Psychological Assessment

The participants were recruited and asked to complete a set of questionnaires, including the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C), Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI). Details of the measures will be further introduced as follows.

PCL-C is an easily administered self-report measure, and consists of 17 items which correspond directly to DSM-IV PTSD symptoms. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale using anchors ranging from one “not at all” to five “extremely,” reflecting the extent to which the particular symptom disturbed the respondent during the past month36. The Chinese version of the PCL was adapted by a stringent two-stage process of translation and back translation. Adequate levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α above. 77) have been previously reported for the total scale and three subscales37. In this study Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.928 and participants of the sample were instructed to complete the PCL-C referring to the “explosions of Tianjin.”

PTGI was developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun to assess perceived positive changes after trauma. The inventory consists of five subscales comprising 21 items: personal strength, new possibilities, relating to others, appreciation of life, and spiritual change7. The Chinese version of PTGI was developed through translation and back-translation. This version is a six-point scale ranging from 0 (I did not experience this change after the traumatic event) to 5 (I experienced this change to a very high degree after the traumatic event). The internal consistency of mean PTGI scores was very good in the sample (21 items, α = 0.939).

PCL-C score of 38 points was considered as the cutoff value for PTSD diagnosis in the actual screening38. In the analysis of PTGI scores, a histogram was used to examine logical cut-off scores for participants identified as “high” and “low” growth reporters. The mean for the sample was 63.62, and “high” growth reporters were identified as those with scores of 80 or higher. All participants were divided into three groups according to their scores of PCL-C and PTGI: 1) In the control group (n = 30), scores of PCL-C and PTGI were both lower than the cut-off scores. MeanPCL-C = 27.10, SDPCL-C = 4.91, MeanPTGI = 49.50, SDPTGI = 16.88; 2) In the PTSD group (n = 30), the participants scored higher than 38 in PCL-C but lower than 80 in PTGI, MeanPCL-C = 43.31, SDPCL-C = 7.61, MeanPTGI = 53.01, SDPTGI = 9.04; 3) In the PTG group (n = 30), compared with the PTSD group, the PCL-C’s scores were lower than 38 but the PTGI’s scores were higher than 80, MeanPCL-C = 25.03, SDPCL-C = 5.84, MeanPTGI = 88.35, SDPTGI = 7.69. The details of the groups are presented in Table 2. The scores of PCL-C and PTGI among groups are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The mean scores and SD of PCL-C and PTGI among control, PTSD and PTG group.

| Group | Survey | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| CON (n = 30) | PCL-C | 27.10 | 4.91 |

| PTGI | 49.50 | 16.88 | |

| PTSD (n = 30) | PCL-C | 43.31 | 7.61 |

| PTGI | 53.01 | 9.04 | |

| PTG (n = 30) | PCL-C | 25.03 | 5.84 |

| PTGI | 88.35 | 7.69 |

Materials and Procedures

45 affective pictures that included 15 pleasant pictures (valence < 3; arousal > 4), 15 unpleasant pictures (valence < 3; arousal > 6) and 15 neutral pictures (valence 4.5–5.5; arousal < 3) were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS, Centre for the Psychophysiological Study of Emotion and Attention, 1994). All pictures were adjusted by Photoshop to keep the same size (768 × 576 pixels) in height and width. Participants were sitting on a chair in a quiet room, The affective pictures were presented via E-Prime software (E-Prime 2.0, Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA) on a 21.5 in. display monitor, 70 cm away from each subject’s face (viewing angle 24°). A white cross hair was first presented at the center of a black background for 20 s (resting period) and then a stimulation that consisted of 3 affective pictures was shown for 45 s (stimulation period, included 1 pleasant, 1 unpleasant and 1 neutral picture, each picture was shown for 15 s). The stimulation period was successively followed by the second resting period. There were 5 resting periods and 5 stimulation periods in total. The order of presenting pictures was randomized in each stimulation period.

The participants were asked to sit during ECG and fNIRS data acquisition. The physiological data were acquired using Biopac MP150 for Windows (Biopac Systems, Inc., Aero Camino, CA) and stored on the hard drive of a Windows XP laptop. Heart rate data were acquired using the electrocardiogram (ECG) modules of the Biopac system. The ECG signal was amplified by a gain of 1000, filtered with a Hamming windowing function, and with a 60-Hz notch filter. ECG was recorded using two disposable Ag/AgCl electrodes pre-coated with electrolyte gel: one was placed on the right side of the upper torso, 1 cm below the clavicle; and the second, on the inside of the left wrist. All data were sampled at 1,000 Hz, digitized at 16 bit A/D resolution, and amplified using the respective modules of the Biopac system.

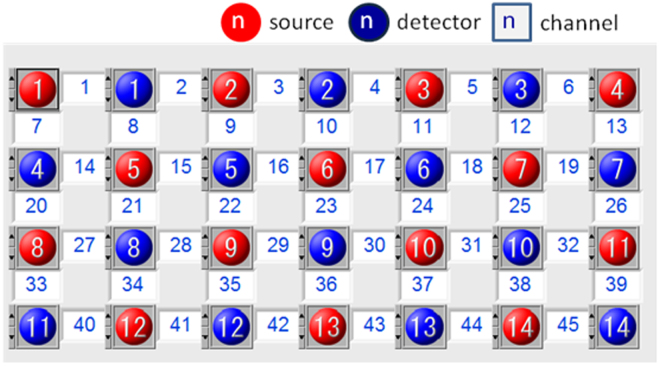

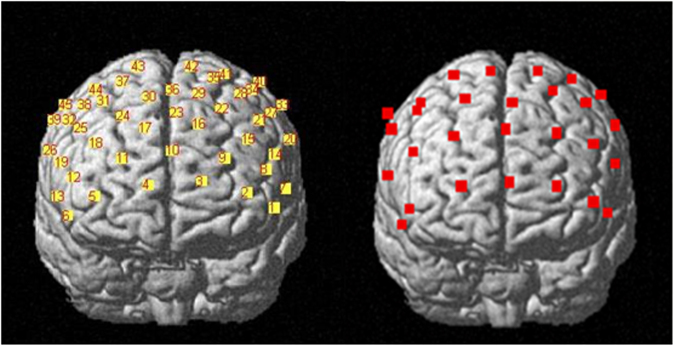

In order to collect fNIRS data, a 52-channel NIRS instrument (LABNIRS, Shimadzu) was used to measure relative concentrations of [oxy-Hb] and [deoxy-Hb]. The instrument used three wavelengths of the near-infrared light (780, 805 and 830 nm). They were combined with a beam coupler and led to the surface of the scalp by a flexible 1 mm diameter optical fiber (NIRS probe). The distance between the source and detector probes was set at 30 mm, and within that distance the instrument could measure the area at 20–30 mm below the scalp, which corresponds to the surface of the cerebral cortices39. A plastic hat with probes was carefully fixed on the head of the participants, symmetrically using an elastic band. The size of the detective area was 12 cm × 20 cm, and on the hat 28 probes (14 sources and 14 detectors) were arranged in a matrix pattern, 30 mm apart from each other. The most anterior row of probes was on the Fp1–Fp2 line following the international 10/20 system used in electroencephalography. The probes on the shell measured the relative concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin at 45 points on the subject’s forehead areas. In total, 21 left anterior and 21 right anterior channels were averaged to measure the activities in the left and right PFC respectively (Fig. 1). The time resolution was set at 0.1 s. To seek the cortical loci responsible for the observed hemoglobin concentration changes, NIRS probe and channel locations were registered to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. First, five anatomical landmarks (nasion, inion, Cz, left and right preauricular points) and all NIRS probes were digitized using a three-dimensional digitizer (FASTRAK, Polhemus, Vermont, USA). Coordinates of channels in the real space were calculated simply as intermediate points between sources and detectors. Then, the NIRS probe and channel positions were rendered onto the MNI standard brain using the NFRI toolbox40 implemented in the NIRS-SPM software41. Coordinates obtained from individuals in the MNI space were averaged across the subjects (Fig. 2). Finally, each participant’s coordinates were exported and saved as Brodmann’s areas (BA) txt.

Figure 1.

Labels of fNIRS probes and channels.

Figure 2.

Channel positions rendered onto the cortical surface of the MNI standard brain.

Data Analysis

HRV data analysis

First, all data were visually inspected prior to analysis, any ectopic/non-sinus beats, such as atrial tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, and atrial premature beats, were identified and removed after visual inspection. Meanwhile, the motion artifacts were isolated through independent component analysis. Second, the power of the low and high frequency components were evaluated by using the analysis function for heart rate variability of Acknowledge 4.2 software. Third, measures of the low and high frequency of HRV data were natural-log transformed to normalize their skewed distributions. Finally, all statistical data were coded and entered into SPSS for windows version 20 (IBM SPSS Statistics), One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to analyze emotion effects in three emotion conditions (negative, neutral and positive) among three groups.

Oxygenated hemoglobin analysis

Relative changes in oxygenated hemoglobin were analyzed using procedures previously developed by Plichta et al.42 programmed in Matlab (2013a, The MathWorks Inc., MA,USA) which by and large are comparable to typical fMRI analysis based on the general linear model (GLM) framework. In order to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, a highpass filter based on a discrete cosine transform was employed. Beta values of event-triggered signals were obtained through the GLM, and then the betas of the DLPFC channel (overlap DLPFC area more than 50%) were averaged among the subjects within three groups (control, PTSD and PTG) and under three emotion conditions (negative, neutral and positive). At last, mean values of these DLPFC betas were analyzed by means of repeated measures ANOVA. Data are provided as means of beta × 103 (unitless) throughout the text. Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS for windows version 20 (IBM SPSS Statistics).

Results

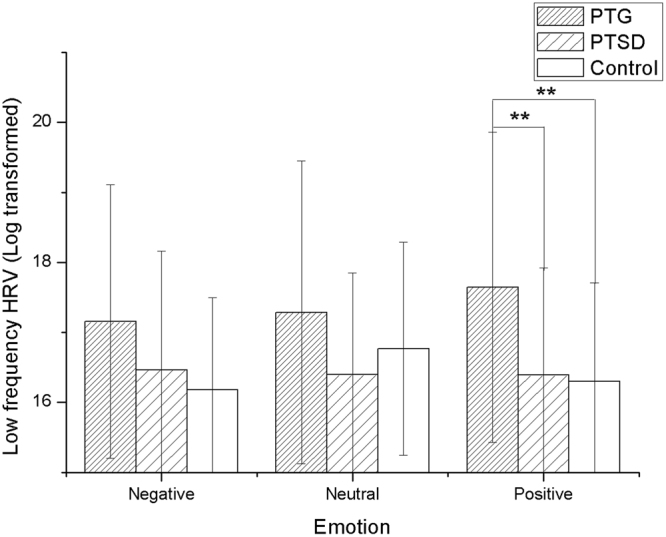

One-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference among groups for the power of low frequency component in negative [F(2, 89) = 2.675; p = 0.045] and positive [F(2, 89) = 5.499; p = 0.006] affective stimulating conditions, but no difference in neutral [F(2, 89) = 1.965; p = 0.146] condition. Bonferroni multiple test corrections for the ANOVA post-hoc comparisons suggested that while performing negative pictures, there was no difference for the power of low frequency between PTG and control group (p = 0.027 > 0.025). Moreover, no difference was found between PTG and PTSD group (p = 0.114 > 0.025), no difference was found between PTSD and control groups (p = 0.515 > 0.025). Meanwhile, Bonferroni multiple test corrections revealed that while performing positive pictures, the power of low frequency of PTG was higher than control group (p = 0.004 < 0.025) and PTSD group (p = 0.007 < 0.025), but there was no difference between PTSD and control group (p = 0.844 > 0.025) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Significant group differences in the negative and positive affective pictures stimulating between the control group and the PTG group in the low frequency HRV, which showed that the PTG group had higher low frequency HRV *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

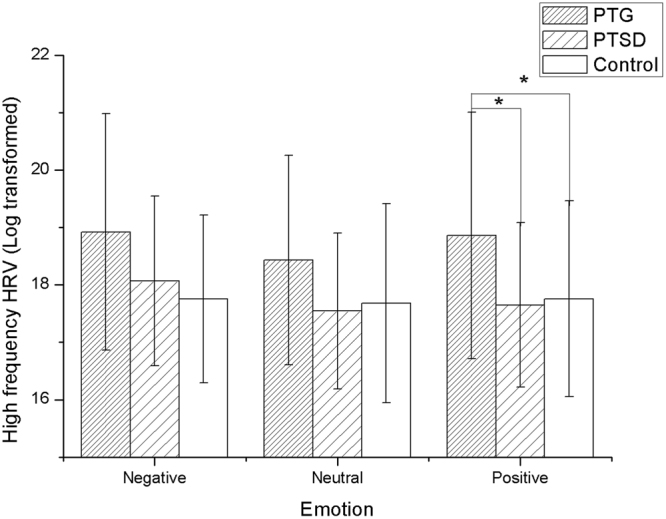

A significant difference was also found among the groups for the power of high frequency component while performing negative [F(2, 89) = 2.519; p = 0.046] and positive[F(2, 89) = 4.222; p = 0.018] pictures by the one-way ANOVA analysis, but no difference was found in neutral [F(2, 89) = 1.557; p = 0.217] condition. Bonferroni multiple test corrections showed that there was no difference for the power of high frequency between PTG and control group (p = 0.040 > 0.025) in the condition of negative pictures stimulating, and no difference was found between PTG and PTSD group (p = 0.080 > 0.025). Meanwhile, PTSD had no difference compare with control group (p = 0.756 > 0.025). However, while performing positive pictures, the power of high frequency of PTG was higher than control group (p = 0.019 < 0.025) and PTSD group (p = 0.010 < 0.025), but no difference was observed between PTSD and control groups (p = 0.815 > 0.025). The result of high frequency is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Significant group differences in the negative and positive affective pictures stimulating between the control group and the PTG group in the high frequency HRV, which showed that the PTG group had higher high frequency HRV *p < 0.05.

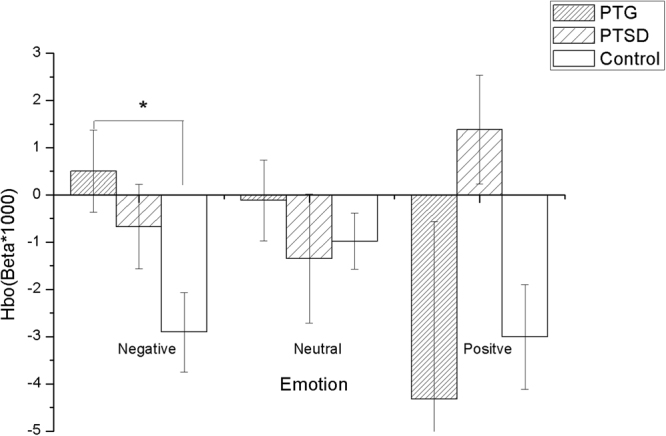

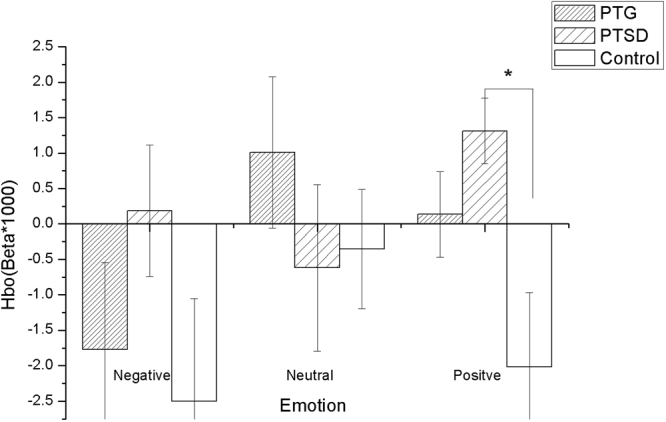

The negative, neutral and positive betas of left and right DLPFC among three groups were analyzed by the repeated measures ANOVA analysis. The results showed that there is a significant overall difference between groups in left (F(2,87) = 4.960, p = 0.009) and right DLPFC (F(2,87) = 7.859, p = 0.001) while performing affective pictures, but no significant effect of (emotion × group) interaction in left (F(2,87) = 1.889, p = 0.157) and right DLPFC (F(2,87) = 1.276, p = 0.284). We applied Bonferroni multiple test corrections for the ANOVA post-hoc comparisons, the results revealed that the oxygenated hemoglobin level of left DLPFC in PTG is higher than in the control group while performing negative affective pictures (P = 0.004 < 0.025), but no difference was found in PTSD (p = 0.070 > 0.025) (Fig. 5). In contrast, the Bonferroni multiple test corrections for the ANOVA post-hoc comparisons showed an increased oxygenated hemoglobin level of the right DLPFC in PTSD while performing positive affective pictures (P = 0.013 < 0.025), but no difference was found in PTG (P = 0.256 > 0.025) (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

PTG showed a higher HbO (oxygenated hemoglobin) level of the left DLPFC in the negative affective pictures stimulating than the control group *p < 0.05.

Figure 6.

PTSD showed a higher HbO (oxygenated hemoglobin) level of the right DLPFC in the positive affective pictures stimulating than the control group *p < 0.05.

Discussion

The ability of emotion regulation is related to a number of important psychological outcomes, such as attention, decision making, memory, physiological responses, and social interactions43. Moreover, emotion regulation has an important role in posttraumatic experience, and the processes of both PTSD and PTG might be influenced by emotional experiences, responses and expressions. HRV is a sensitive and important psychophysiological index of emotion regulation capacity, so HRV has been employed often in PTSD research as an important marker of emotion regulation in trauma. Moreover, HF-HRV is mediated by parasympathetic (vagal) activity while LF-HRV is regulated by baroreflex function18.

Our study firstly investigated the characteristics of HRV among PTG and PTSD in response to the presentation of affective pictures. The results demonstrated that the low and high frequency components of HRV in PTG were significantly higher than control group while performing positive affective pictures stimulating. However, we did not observe any significant difference between PTG and the control groups during negative and neutral affective pictures stimulating. These results of HRV experiment suggested that PTG having higher vagal function may allow persons to more efficiently process emotional stimuli.

Although some published literatures have clearly shown that PTSD often had a lower HF-HRV than control, our results indicated that PTSD has no differences of HF-HRV when compared with the control group in response to different affective conditions. The reason could be that the population of PTSD participants is heterogeneous and complicated, with different traumatic events (e.g. war, disaster, terrorist assault) and demographics (e.g. sex, age, religion)44. We believe that these factors may have impacted on the relationship between PTSD and HRV.

Activities in prefrontal cortex correlates with vagal function of heart rate variability during emotion regulation. Based on this, our research explored the role of the prefrontal cortex in emotional experiencing between PTG and PTSD. Discovering the different characteristics of emotional experiencing in PTG and PTSD, the results demonstrated that the left DLPFC is more involved in the negative affective experiencing in PTG, whereas the right DLPFC is more involved in the positive affective experiencing in PTSD. The DLPFC is widely concerned because of its overrepresentation in cognitive process such as reappraisal, expressive suppression, working memory, reasoning, cognition and emotion processing, which regulate many behavioral reactions, such as motor behaviors45, approach and avoidance via its connections to the other brain areas, such as the ventral striatum, amygdala and insular et al.46. Many studies revealed that DLPFC is closely involved post-traumatic experience. On one hand, DLPFC plays an important role in the recovery from PTSD, and greater DLPFC response in PTSD patients may reflect engagement of cognitive control networks that are beneficial for emotional and cognitive functioning32. On the other hand, the delta- regional grey matter volume in DLPFC is positively and significantly associated with PTG, and DLPFC seems to be the main neural correlate of PTG35. These results showed that DLPFC area is not only involved in PTSD, but might also correlate closely with PTG. The present study implied that DLPFC has lateralization effects in the involvement of PTSD and PTG, and future study is needed to further answer the roles of bilateral parts of the DLPFC in maintaining emotional and cognitive aspects of PTSD and PTG.

Based on the above statement, our findings in total suggested an important relationship between the emotion regulation, HRV, and prefrontal cortex function, provided the evidence that prefrontal cortex has a regulatory role in autonomic nerve system during emotion regulation correlate with posttraumatic experience. A considerable amount of studies on PTSD covered many fields during the last decades. As a result, rapid progress in our understanding of psychopathological conditions of PTSD has been made due to the vast research of neural and other biological correlates of these phenomena. PTG represents the experience of positive change which occurs as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life crises. It is manifested in a variety of ways, including an increased appreciation for life in general, more meaningful interpersonal relationships, an increased sense of personal strength, changed priorities, and a richer existential and spiritual life6. During the past decades the research on PTG mostly focused on the correlation with trauma (such as traumatic exposure), personality trait (such as resilience, rumination and cognitive coping)47,48 and social support49. However, to date there is extremely little research on the neuro-biological mechanisms of PTG compared with PTSD. As a result, PTG remains poorly understood and controversial. Because current studies on PTG are mostly dependent on self report some researchers even doubt that the fact that some people seem to grow after trauma, and may deem this illusory50. The present study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first study to investigate PTG from the perspective of HRV and hemodynamic responses, and provides more objective evidence to support that PTG is an objective phenomenon.

Of course, there are several limitations in this study. Firstly, the method of group division maybe inappropriate. In this study, we divided the participants into control, PTSD and PTG groups according to their scores of PCL-C and PTGI surveys, taking the view that PTSD and PTG are two opposite outcomes of trauma. However, the correlation between PTSD and PTG still remains controversial. Although our previous research found no correlation between PTSD and PTG51, some studies hold the point of view that there is a negative correlation between them and they may coexist48,52, while other research suggested that PTSD is positively correlated with PTG53,54. In this regard, there might be some individuals who would score highly both in PCL-C and PTGI, and this group was not investigated in this study because of limited participants. Secondly, this research is a cross-sectional study, and the data collection was conducted approximately 12 months after the serious explosions. Therefore, to a certain degree, the characteristics of the emotional experiencing we have drawn from the data is isolated and incomplete, and a retrospective and longitudinal investigation is needed to overcome this shortage. Thirdly, the sample size we recruited was relatively small, which might influence the generalization of the conclusion. Moreover, fitness might be a potential confounding factor influencing the performance of HRV. In future studies, the assessment of fitness should be considered and the relevant index reflecting aerobic fitness, such as total physical activity and maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), should be collected.

Acknowledgements

We thank engineers Mengchai Mao, Qingwu Zeng, Jianbo Hu and Wenhao Wu for their help in technical guidance on fNIRS and HRV. We also thank Kankan Wu and Dongming Cui for the recruitment of participants. This work is supported by the Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (KLMH2015ZG01).

Author Contributions

Chuguang Wei designed the experiment, analyzed the data, and wrote the main manuscript text, Jin Han prepared the materials and equipments and did a lot work for the data collection and analysis, Yuqing Zhang made a lot of guidance and all funds supports for the whole research, Walter Hannak revised the manuscript, Yanyan Dai made some work on data analysis, Zhengkui Liu prepared the participants and room conditions. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gurevich M, Devins GM, Rodin GM. Stress response syndromes and cancer: conceptual and assessment issues. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:259–281. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishi, D., Matsuoka, Y. & Kim, Y. Research Posttraumatic growth, posttraumatic stress disorder and resilience of motor vehicle accident survivors. (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Laufer A, Solomon Z. Posttraumatic symptoms and posttraumatic growth among Israeli youth exposed to terror incidents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:429–447. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.4.429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alisic E, Van der Schoot T, van Ginkel JR, Kleber RJ. Looking beyond posttraumatic stress disorder in children: Posttraumatic stress reactions, posttraumatic growth, and quality of life in a general population sample. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:1455–1461. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jim HS, Jacobsen PB. Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth in cancer survivorship: a review. The Cancer Journal. 2008;14:414–419. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calhoun LG, Cann A, Tedeschi RG, McMillan J. A correlational test of the relationship between posttraumatic growth, religion, and cognitive processing. Journal of traumatic stress. 2000;13:521–527. doi: 10.1023/A:1007745627077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of traumatic stress. 1996;9:455–471. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association, A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). (American Psychiatric Pub, 2013).

- 9.Aldao A. The future of emotion regulation research capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8:155–172. doi: 10.1177/1745691612459518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ansorge, S. B. Thinking about feelings: affect tolerance, affect regulation and responses to psychological trauma. (1995).

- 11.Weiss NH, Tull MT, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. The relative and unique contributions of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity to posttraumatic stress disorder among substance dependent inpatients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;128:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens NR, et al. Emotion regulation difficulties, low social support, and interpersonal violence mediate the link between childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behavior Therapy. 2013;44:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehring T, Quack D. Emotion regulation difficulties in trauma survivors: The role of trauma type and PTSD symptom severity. Behavior therapy. 2010;41:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tull MT, Barrett HM, McMillan ES, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen SE, Berenbaum H. Are Specific Emotion Regulation Strategies Differentially Associated with Posttraumatic Growth Versus Stress? Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2015;24:794–808. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2015.1062451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei W, Li X, Tu X, Zhao J, Zhao G. Perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulations as mediators of the relationship between enacted stigma and post-traumatic growth among children affected by parental HIV/AIDS in rural China. AIDS care. 2016;28:99–105. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1146217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarczok MN, et al. Autonomic nervous system activity and workplace stressors—a systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37:1810–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldstein DS, Bentho O, Park MY, Sharabi Y. Low-frequency power of heart rate variability is not a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone but may be a measure of modulation of cardiac autonomic outflows by baroreflexes. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:1255–1261. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.056259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thayer JF, Åhs F, Fredrikson M, Sollers JJ, Wager TD. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingjaldsson JT, Laberg JC, Thayer JF. Reduced heart rate variability in chronic alcohol abuse: relationship with negative mood, chronic thought suppression, and compulsive drinking. Biological psychiatry. 2003;54:1427–1436. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01926-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heathers, J. A. Everything Hertz: methodological issues in short-term frequency-domain HRV. Frontiers in physiology5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Friedman BH. An autonomic flexibility–neurovisceral integration model of anxiety and cardiac vagal tone. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahbeh H, Oken BS. Peak high-frequency HRV and peak alpha frequency higher in PTSD. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback. 2013;38:57–69. doi: 10.1007/s10484-012-9208-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hauschildt M, Peters MJ, Moritz S, Jelinek L. Heart rate variability in response to affective scenes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychology. 2011;88:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maier SU, Hare TA. Higher Heart-Rate Variability Is Associated with Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Activity and Increased Resistance to Temptation in Dietary Self-Control Challenges. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2017;37:446–455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2815-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakreida K, Gauggel S. P 130. The impact of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in the control of heart rate variability investigated by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2013;124:e127. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.04.208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Åhs F, Sollers JJ, Furmark T, Fredrikson M, Thayer JF. High-frequency heart rate variability and cortico-striatal activity in men and women with social phobia. NeuroImage. 2009;47:815–820. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane RD, et al. Neural correlates of heart rate variability during emotion. Neuroimage. 2009;44:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonçalves, E. M. Stress prevention by modulation of autonomic nervous system (heart rate variability): A preliminary study using transcranial direct current stimulation. (2012).

- 30.Ray RD, Zald DH. Anatomical insights into the interaction of emotion and cognition in the prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36:479–501. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aupperle RL, et al. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation during emotional anticipation and neuropsychological performance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:360–371. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyoo IK, et al. The neurobiological role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in recovery from trauma: longitudinal brain imaging study among survivors of the South Korean subway disaster. Archives of general psychiatry. 2011;68:701–713. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen H, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in posttraumatic stress disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:515–524. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabe S, Zöllner T, Maercker A, Karl A. Neural correlates of posttraumatic growth after severe motor vehicle accidents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:880. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakagawa, S. et al. Effects of post-traumatic growth on the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex after a disaster. Scientific reports6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Herman, D. S., Huska, J. A. & Keane, T. M. In Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. (International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies San Antonio).

- 37.Wu KK, Chan SK, Yiu VF. Psychometric properties and confirmatory factor analysis of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for Chinese survivors of road traffic accidents. Hong Kong J Psychiatry. 2008;18:144–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ning, L., Guan, S. & Liu, J. Impact of personality and social support on posttraumatic stress disorder after traffic accidents. Medicine96 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Toronov V, et al. Investigation of human brain hemodynamics by simultaneous near-infrared spectroscopy and functional magnetic resonance imaging. Medical physics. 2001;28:521–527. doi: 10.1118/1.1354627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamoto M, Dan I. Automated cortical projection of head-surface locations for transcranial functional brain mapping. Neuroimage. 2005;26:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ye JC, Tak S, Jang KE, Jung J, Jang J. NIRS-SPM: statistical parametric mapping for near-infrared spectroscopy. Neuroimage. 2009;44:428–447. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plichta M, Heinzel S, Ehlis A-C, Pauli P, Fallgatter A. Model-based analysis of rapid event-related functional near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) data: a parametric validation study. Neuroimage. 2007;35:625–634. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldin PR, McRae K, Ramel W, Gross JJ. The Neural Bases of Emotion Regulation: Reappraisal and Suppression of Negative Emotion. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:577–586. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagpal M, Gleichauf K, Ginsberg J. Meta-analysis of heart rate variability as a psychophysiological indicator of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Treat. 2013;3(2167–1222):1000182. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cieslik EC, et al. Is there “one” DLPFC in cognitive action control? Evidence for heterogeneity from co-activation-based parcellation. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:2677–2689. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haber SN, Knutson B. The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:4–26. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ai AL, Tice TN, Whitsett DD, Ishisaka T, Chim M. Posttraumatic symptoms and growth of Kosovar war refugees: The influence of hope and cognitive coping. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2007;2:55–65. doi: 10.1080/17439760601069341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu, K., Zhang, Y., Liu, Z., Zhou, P. & Wei, C. Coexistence and different determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth among Chinese survivors after earthquake: role of resilience and rumination. Frontiers in psychology6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Morris B, Chambers SK, Campbell M, Dwyer M, Dunn J. Motorcycles and breast cancer: The influence of peer support and challenge on distress and posttraumatic growth. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20:1849–1858. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Börner, M. Real and illusory reports of posttraumatic growth and their correlation with well-being: an empirical examination with special focus on defence mechanisms, University of Nottingham, (2016).

- 51.Wei C, Han J, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Hannak W. The characteristics of emotional response of post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth among Chinese adults exposed to an explosion incident. Frontiers in Public Health. 2017;5:3. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu Z, Xu J, Sui Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth coexistence and the risk factors in Wenchuan earthquake survivors. Psychiatry research. 2016;237:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jin Y, Xu J, Liu D. The relationship between post traumatic stress disorder and post traumatic growth: gender differences in PTG and PTSD subgroups. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2014;49:1903–1910. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0865-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solomon Z, Dekel R. Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic growth among Israeli ex‐pows. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:303–312. doi: 10.1002/jts.20216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]