Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the feasibility and the safety of robotic single-site radical hysterectomy (RSSRH) plus pelvic lymphadenectomy (PL) in endometrial or cervical cancer.

Methods

Patients with endometrial cancer (EC) International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage II, early cervical cancer (ECC) FIGO stage IB1 or locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC) FIGO stage IB2–IIB with clinical response ≥50% after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) were enrolled in a prospective cohort trial. All cases were performed using the da Vinci Si Surgical Single Site System®.

Results

Between April 2014 and November 2016, twenty patients were included in our pilot study. Three and 17 patients underwent type B1 or C1 RSSRH plus PL, respectively. The median age of patients was 46 years (range, 36–68 years) and the median body mass index was 23.5 kg/m2 (range, 19.1–36.3 kg/m2). The median total operative time was 190 minutes (range, 90–310 minutes). The median blood loss was 75 mL (range, 20–700 mL) and the median number of pelvic lymph nodes removed was 16 (range, 5–27). No laparoscopic/laparotomic conversions were reported and the median time to discharge was 6 days (range, 4–16 days). No intra-operative complications occurred while 4 (20%) post-operative complications were reported: one pelvic abscess, one lymphorrea, one bowel perforation, and one vaginal dehiscence.

Conclusion

RSSRH plus PL is technically feasible in patients affected by gynecological cancer.

Keywords: Robotic Surgical Procedures, Hysterectomy, Lymph Node Excision, Uterine Cervical Neoplasms, Endometrial Neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays radical hysterectomy plus pelvic lymphadenectomy (RHPL) remains a widely used therapeutic option for many uterine malignancies. Due to the complexity of this intervention and to the number of related complications, minimally invasive procedures have been used for RHPL since their arrival in order to make this procedure more acceptable for patients [1,2]. Multiple retrospective and prospective studies on traditional laparoscopy (LAP2 study) and retrospective studies on robotically assisted laparoscopy for the treatment of uterine cancers have shown reduced blood loss, shorter hospital stay as well as decreased incidence rates and severity of postoperative surgical complications compared with laparotomy [3,4]. Minimally invasive techniques maintain equivalent oncologic results with regard to the number of dissected lymph nodes and overall disease-free survival rates. Compared with traditional laparoscopy, robotic surgery has a lower rate of conversion to laparotomy, lower blood loss and provides significant ergonomic advantages for the surgeon facilitating execution of complex oncologic procedures, especially in obese patients [5].

Recently laparoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) has emerged to increasingly reduce invasiveness, at the same time maintaining an adequate efficacy compared to multiport approaches. It not only offers a better cosmetic result (incision hidden by the umbilical scar) but also potentially reduces postoperative pain and faster recovery [6,7]. Nevertheless, LESS remains a challenging surgical technique mainly due to the lack of triangulation among the surgical instruments. In the last several years, the da Vinci Single-Site Surgery technique was introduced into clinical practice to perform general, urologic and gynaecologic procedures robotically in a LESS surgery scenario, with encouraging preliminary results [6,7,8,9,10]. Nevertheless, robotic single-site radical hysterectomy (RSSRH) is still uncommon worldwide probably because of technical difficulties and the absence of a standardized technique. We present a pilot study to evaluate the feasibility and safety of RSSRH plus pelvic lymphadenectomy (PL) in patients with cervical and endometrial cancer (EC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a single-institutional pilot study that involved patients from the “Regina Elena” National Cancer Institute of Rome with primary cervical or endometrial carcinoma.

1. Study design

Patients with clinical International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage II endometrial adenocarcinoma, IB1–IIA1 cervical carcinoma, and IB2–IIB cervical cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) with clinical response ≥50% were enrolled to perform RSSRH plus PL.

All patients were evaluated preoperatively through: anamnesis, physical examination, vaginal-pelvic examination, chest X-ray, trans-vaginal ultrasound scan, and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2 or less, an adequate renal, hepatic, and cardiac function, and an adequate granulocyte and platelet count ≥2,000/mL and ≥100,000/mL, respectively were required for this surgery. Lymph node and/or adnexal involvement at computed tomography/MRI, uterine size ≥12 weeks of pregnancy and the impossibility to sustain a steep Trendelenburg position were considered the exclusion criteria for the RSSRH. The da Vinci Si Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was used by the same surgical team consisting of the primary surgeon (E.V.), the bedside assistant (G.C.) and a robotics-dedicated scrub technician and circulating nurse.

The following data were collected prospectively: clinical patient characteristics, pathologic characteristics (tumor stage and grade, surgical margins, status and number of removed pelvic lymph nodes, length of dissected parametrial tissue, and vagina), operative time (considering surgical incision to skin closure), estimated blood loss, blood transfusions (if hemoglobin value was <7 g/dL), length of hospitalization, post-operative complications divided into early (in the first 30 days after surgery) and late complications (more than 30 days after surgery). Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAEs) version 4.0 was used to define complications [11]. Moreover, type of adjuvant therapy (radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy), median follow up in one month and recurrence were recovered. Adjuvant therapy was tailored to the pathologic findings at primary operation after multidisciplinary tumor board (gynecologic oncology, pathology, radiation oncology, medical oncology) discussion. Treatment was based on the results of prospective, randomized clinical trials and National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines [12]. All the information concerning the follow up was collected over telephone calls to the patients.

The study was approved by our institutional review board (#0011950/16). All the patients enrolled completed an informed consent for surgery and preoperative evaluations in accordance with the ethical principles of the local and the international regulations (declaration of Helsinki) [13].

2. Surgical technique

All patients were administered antibiotic prophylaxis (Augmentin 2.2 g intravenously; GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) and perioperative low molecular weight enoxaparin (Lovenox 40 mg/24 hr subcutaneously; Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC, Bridgewater, NJ, USA). The vaginal cavity was cleansed with povidone iodine solution and a Foley catheter was placed in the bladder. No uterus manipulator devices were used, but the cervix was closed with a modified tenaculum called “simple nebs arising incision landmark” (SNAIL®) [14]. A medical grade silicone balloon, named colpo-pneumo occluder (CooperSurgical, Inc., Trumbull, CT, USA) was also placed in the vagina in order to preserve an adequate pneumoperitoneum during colpotomy. In addition, intraoperative lower extremity sequential compression devices for venous thrombosis prophylaxis were used. All procedures were performed under general endotracheal anesthesia.

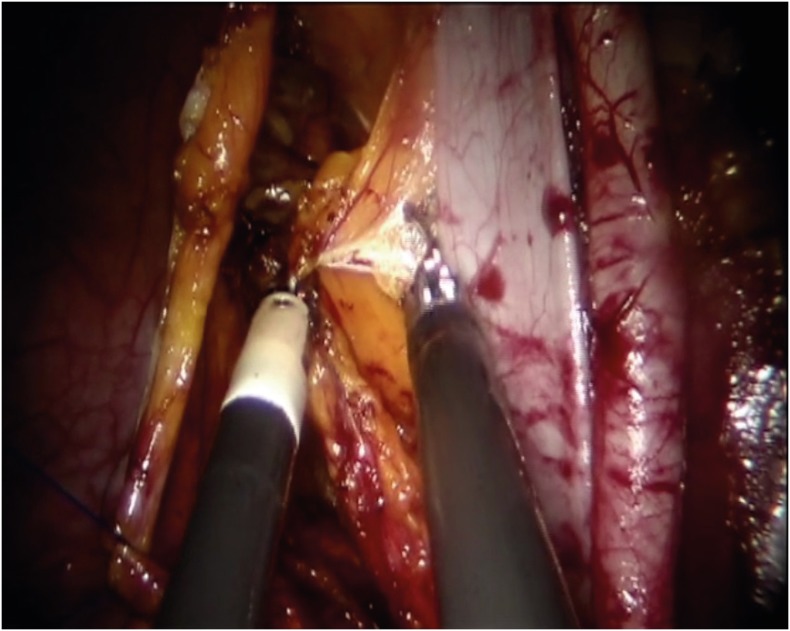

A 2 cm long incision over the lower rim of the umbilicus, down to the level of the fascia was made after lubrication of the Single-Site™ port (Intuitive Surgical Inc.) by dipping it in a sterile solution (e.g., saline or water). Using an atraumatic clamp, the Single-Site™ port was grasped just above the lower rim. The leading edge of the folded port was inserted into the incision with a downward motion, while counter-traction was provided by retractors within the incision. Insufflation to reach a pneumoperitoneum of approximately 12 mmHg started. Next, the table was placed in the Trendelenburg position (30 degrees). The da Vinci Si 8.5 mm 30-degrees endoscope was inserted vertically and used during the whole course of surgery. Subsequently, a 5×250 mm curved cannula (Arm 2) was lubricated and inserted through the designated lumen while the external rim of the port was held by the assistant to avoid displacement. The cannula was guided near the uterus and then held still to allow docking. This was done by holding the cannula still in one hand while the other hand brings and mounts the arm to the second 5×250 mm curved cannula (Arm 1). Finally, the instruments were introduced: a monopolar spatula or scissors, for the lymphadenectomy step, on Arm 2 and a bipolar Maryland on Arm 1 to perform right lymphadenectomy and reverse for left lymphadenectomy (Fig. 1). The assistant's 5 mm accessory cannula, with which the assistant holds and moves either a suction/irrigator or a 5-mm endo-clip instrument, was inserted in last. A careful inspection of the entire abdominal cavity was performed with the robotic endoscope in order to identify any suspicious peritoneal lesions that would exclude the patient from having the procedure completed by robotic technique. Moreover, peritoneal washing was routinely performed.

Fig. 1.

Use of bipolar Maryland on Arm 1, that works on the left side, to perform right lymphadenectomy.

A radical type B1 or C1 hysterectomy plus PL, according to Querleu and Morrow classification [15], was performed beginning from surgical preparation of the retroperitoneal spaces: Paravesical space, Lasko's fossa and medial pararectal fossa or “Okabayashi's pararectal space,” In case of positive pelvic nodes at definitive examination, after adequate counseling, a laparoscopic single port aortic lymphadenectomy was performed 3 weeks after the RSSRH until the left renal vein. In all patients, the lymph nodes were placed in the endobag and were extracted throughout the vagina with a surgical specimen. The vaginal vault was closed with single stitches using the vaginal way and each layer of the access port was sutured separately. Starting from the end of surgery for the first 24 hours, analgesic therapy with tramadol 100 mg plus ketorolac 60 mg was administered by continuous infusion. Paracetamol 1,000 mg was administered only on patient's demand. Visual analog scale was used for pain assessment. In all cases the urine catheter was removed 12 hours after B1 radical surgery and 3 days after operation after C1. In these last cases, an intermittent self-catheter was used for voiding until the residual urine volume was less than 100 mL. Criteria considered for discharge were physiologic recovery of bladder and rectal function and no pain.

RESULTS

1. Patient characteristics

A total of twenty patients underwent RSSRH plus PL from April 2014 to November 2016. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Four patients had undergone previous abdominal surgical procedures. A total of 17 patients underwent type C1 RSSRH and 3 patients type B1. A PL was performed in all cases. No conversion to laparoscopy or laparotomy was needed.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the 20 women who underwent RSSRH with PL.

| Characteristics | Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 46 (36–68) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5 (19.1–36.3) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 4 (20) | |

| Type of cancer | ||

| EC (FIGO stage II) | 3 (15) | |

| ECC (FIGO stage IB1) | 11 (55) | |

| LACC (FIGO stage IB2–IIB) | 6 (30) | |

| Grading | ||

| G1 | 1 (5) | |

| G2 | 6 (30) | |

| G3 | 13 (65) | |

| Type of radical surgery | ||

| Type B1 plus PL | 3 (15) | |

| Type C1 plus PL | 17 (85) | |

| ASA score | 2 (1–3) | |

Values are presented as median (range) or number (%).

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; EC, endometrial cancer; ECC, early cervical cancer; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; LACC, locally advanced cervical cancer; PL, pelvic lymphadenectomy; RSSRH, robotic single-site radical hysterectomy.

2. Intra-operative parameters

The median operation time skin-to-skin was 190 minutes (range, 90–310 minutes) and no additional assistant port was necessary. The median blood loss was 75 mL (range, 20–700 mL), no patients required intraoperative, nor postoperative blood transfusions. The median length of dissected parametria was 20 mm (range, 10–25 mm) for the right parametrium and 15 mm (range, 10–35 mm) for the left parametrium and 20 mm (range, 10–50 mm). The median number of pelvic lymph nodes removed was 16 (range, 5–27) and only in one case with complete clinical response after NACT in locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC), 2 nodes were found positive for metastasis. No major intraoperative complications were observed in our cohort (Table 2).

Table 2. Surgical outcome of the 20 women who underwent RSSRH with PL.

| Characteristics | Patients (n=20) |

|---|---|

| Operative time (min) | 190 (90–310) |

| Blood loss (mL) | 75 (20–700) |

| Width right parametrium (mm) | 20 (10–25) |

| Width left parametrium (mm) | 15 (10–35) |

| Length vaginal cuff (mm) | 20 (10–50) |

| Pelvic lymph nodes | 16 (5–27) |

| Major intraoperative complications | 0 |

| Major postoperative complications | 4 (20) |

| Blood transfusion | 0 |

| Conversion to laparoscopy/laparotomy | 0 |

| Reoperation | 3 (15) |

| Hospital stay (day) | 6 (4–16) |

Values are presented as median (range) or number (%).

PL, pelvic lymphadenectomy; RSSRH, robotic single-site radical hysterectomy.

3. Postoperative parameters

We reported the following early postoperative complications in 4 patients (20%): one intestinal perforation, one pelvic abscess, and one dehiscence of the vaginal vault, respectively on the third, the fifth and on the twenty-first postoperative day and one excessive lymphorrhea. The following procedures: a laparotomy in the first case, a laparoscopy in the second one and a vaginal suture were necessary to solve the complications, lymphorrhea resolved spontaneously in one week. No late post-operative complications were reported. The median hospital stay was 6 days (range, 4–16 days) (Table 3).

Table 3. Postoperative complications after RSSRH with PL.

| Types of complication | Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Postoperative short-term (≤30 days) | ||

| Pelvic abscess | 1 (5) | |

| Lymphorrhea | 1 (5) | |

| Bowel perforation | 1 (5) | |

| Vaginal cuff dehiscence | 1 (5) | |

Values are presented as number (%).

PL, pelvic lymphadenectomy; RSSRH, robotic single-site radical hysterectomy.

4. Oncological outcomes

Clinical follow-up took place through physical and vaginal-pelvic examinations every 3 months for the first 2 years after treatment. Adjuvant treatment was performed in 10 patients (50%). Radio-chemotherapy was performed in 2 FIGO stage II EC, in 2 patients with early cervical cancer (ECC) for microscopical parametrial involvement and in one LACC after NACT for nodal involvement. The third patient with EC underwent only adjuvant brachytherapy because cervical involvement was excluded at the final pathologic exam. Four LACC after NACT patients underwent adjuvant radiotherapy for macroscopic residual disease, grade 3, lymph vascular space involvement.

Currently, with a median follow-up of 24 months (range, 5–38 months) 18 patients are alive with no evidence of disease. One patient with LACC and complete pathological response after NACT died after 2 months for brain and spinal cord metastasis and another patient with clinical ECC FIGO stage IB1 but with initial parametrial involvement died after 20 months for distant metastasis (Table 4).

Table 4. Oncological outcomes.

| Adjuvant therapies | Patients |

|---|---|

| None | 10 (50) |

| RT | 4 (20) |

| BRT | 1 (5) |

| RT+CT | 5 (25) |

| Follow-up (mo) | 24 (5–38) |

| Recurrence | 2 (10) |

| NED | 18 (90) |

| AWD | 0 |

| DOD | 2 (10) |

Values are presented as median (range) or number (%).

AWD, alive with disease; BRT, brachytherapy; CT, chemotherapy; DOD, dead of disease; NED, no evidence of disease; RT, radiotherapy.

DISCUSSION

Robotic single-site surgery was created to minimize the surgical approach even for complex interventions in order to reduce recovery time, costs, pain, and improve cosmesis, as already shown with laparoscopic single-site surgery [16,17]. Recent findings suggest that even for selected gynaecologic oncology cases a single-port robotic approach seems safe and feasible with acceptable operative times and perioperative outcomes [18].

Only 4 cases of RSSRH plus PL were reported in the literature, one is a case-report for a FIGO stage IB1 cervical cancer, the other 3 cases have been recently described in a retrospective study and were treated with this procedure for cervical cancers that had no specified stage [18,19]. Another author described a case of a cervical carcinoma treated with RSSRH with sentinel lymph node biopsy [20]. There are no studies available in the literature reporting this intervention in a series of patients. Our study describes the first case series of patients with gynaecological malignancies who underwent RSSRH plus PL with a robotic single-site approach.

In this study patients with FIGO stage IB2–IIB cervical cancer after NACT+RSSRH were included even if, at the present time, the standard treatment for women affected by LACC is concomitant radio-chemotherapy [21]. Recently, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) followed by radical surgery has become one of the alternative treatment options [22]. Possible advantages of NACT prior to surgery include the potential for reducing tumor volume, increasing resectability and helping to control micro-metastatic disease [23]. The development of robotic technology has facilitated the application of minimally invasive techniques in gynecologic oncology [24], and recently also the feasibility of this procedure in LACC after NACT, has been investigated [25].

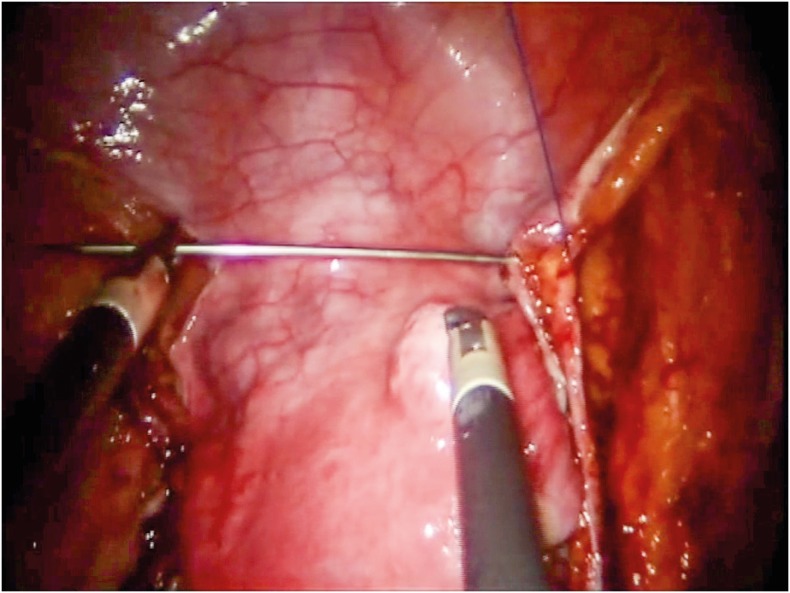

In our previous experience with LESS there were major technical disadvantages which included: collision among instruments, the absence of instrument articulation, and few electrosurgical options compared to conventional robotic surgery [26]. In our previous study, we described many surgical techniques that could help the surgeon solve the obstacles. One surgical measure we commonly use in the LESS approach is the medialization of umbilical arteries using a surgical thread with a straight needle passing through umbilical laminas. In this way, we obtained perfect traction to better open retroperitoneal spaces (Fig. 2). As described above, by switching instruments when changing sides during PL and parametrectomy, allows the surgeon to take advantage of a better working angle. Due to the absence of a standardized technique, as well as the disadvantages described above and longer learning curve respect to the multiport technique. RSSRH is still a poorly understood approach and remains a major challenge for the surgeon. However, reduced recovery time, better cosmesis, low costs and pain are the goals that this technique warrants.

Fig. 2.

Medialization of umbilical arteries using a surgical thread with a straight needle passing through umbilical laminas.

In our casuistry, recovery time is elevated for the high incidence of complications and re-interventions, 20% and 15%, respectively. A part from these cases, the median hospital stay decreases from 6 to 3 days, that is actually a short period considering the complexity of this surgery. Analysing complications in our casuistry, the case of vaginal cuff dehiscence occurring after having sexual intercourse, even though we recommend all the patients to not have sex prior 30 days after the intervention, is not related to the single-site technique especially because we sutured all patients with a vaginal approach. Even in the case of pelvic abscess, we believe it is not related to the technique, because sterility is guaranteed like in other interventions, operative time is similar to standard robotic surgery and antibiotic protocol was the same. The other 2 complications are probably due to the surgeon's low confidence level in using this new technique given the greater disadvantage in lacking instrument articulation compared to the multiport approach. The novel robotic SPIDER® system (TransEnterix, Durham, NC, USA) probably will solve these problems flexible instruments.

Certainly, the impossibility to perform aortic lymphadenectomy until the left renal vein is an important limitation of the robotic single site surgery, because as in our case with positive pelvic lymph nodes at definitive examination, for an adequate lymph nodes staging [27] we need to perform a new surgical treatment.

Final conclusions are difficult to draw because the greatest weakness of our casuistry is the small number of patients, hence comparative studies, and larger cohorts are necessary to demonstrate safety and reproducibility of this new surgical technique as well as to analyse medical costs and long-term outcomes.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Conceptualization: Y.E., C.G.

- Data curation: C.B., B.E.

- Formal analysis: B.E.

- Funding acquisition: V.E.

- Investigation: M.E.

- Methodology: C.G.

- Project administration: B.A.

- Resources: V.E.

- Software: Z.A.

- Supervision: C.G.

- Validation: C.G.

- Visualization: Z.A.

- Writing - original draft: C.G.

- Writing - review & editing: M.E.

References

- 1.Pellegrino A, Vizza E, Fruscio R, Villa A, Corrado G, Villa M, et al. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients with Ib1 stage cervical cancer: analysis of surgical and oncological outcome. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vizza E, Pellegrino A, Milani R, Fruscio R, Baiocco E, Cognetti F, et al. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy in locally advanced stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li G, Yan X, Shang H, Wang G, Chen L, Han Y. A comparison of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy and laparotomy in the treatment of Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park DA, Yun JE, Kim SW, Lee SH. Surgical and clinical safety and effectiveness of robot-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy compared to conventional laparoscopy and laparotomy for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:994–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrado G, Chiantera V, Fanfani F, Cutillo G, Lucidi A, Mancini E, et al. Robotic hysterectomy in severely obese patients with endometrial cancer: a multicenter study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.08.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaouk JH, Autorino R, Kim FJ, Han DH, Lee SW, Yinghao S, et al. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery in urology: worldwide multi-institutional analysis of 1076 cases. Eur Urol. 2011;60:998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheib SA, Fader AN. Gynecologic robotic laparoendoscopic single-site surgery: prospective analysis of feasibility, safety, and technique. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:179.e1–179.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon A, Yoo HN, Lee YY, Lee JW, Kim BG, Bae DS, et al. Robotic single-port hysterectomy, adnexectomy, and lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:322. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tateo S, Nozza A, Del Pezzo C, Mereu L. Robotic single-site pelvic lymphadenectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:631. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogliolo S, Musacchi V, Cassani C, Babilonti L, Gardella B, Spinillo A. Robotic single-site technique allows pelvic lymphadenectomy in surgical staging of endometrial cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22:695–696. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (US) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Uterine and cervical neoplasms, version 1. 2017 [Internet] Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2017. [cited year month day]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/uterine.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute (US) Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.03 [Internet] Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2010. [cited 2017 Aug 1]. Available from: http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Medical Association Inc Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J Indian Med Assoc. 2009;107:403–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barletta F, Corrado G, Vizza E. Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with the use of SNAIL Tenaculum™. A simplified uterine manipulator for the management of early cervical cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;27:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Querleu D, Morrow CP. Classification of radical hysterectomy. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:297–303. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagotti A, Bottoni C, Vizzielli G, Gueli Alletti S, Scambia G, Marana E, et al. Postoperative pain after conventional laparoscopy and laparoendoscopic single site surgery (LESS) for benign adnexal disease: a randomized trial. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:255–259.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yim GW, Jung YW, Paek J, Lee SH, Kwon HY, Nam EJ, et al. Transumbilical single-port access versus conventional total laparoscopic hysterectomy: surgical outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:26.e1–26.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moukarzel LA, Fader AN, Tanner EJ. Feasibility of robotic-assisted laparoendoscopic single-site surgery in the gynecologic oncology setting. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinno AK, Tanner EJ., 3rd Robotic laparoendoscopic single site radical hysterectomy with sentinel lymph node mapping and pelvic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:387. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva E, Silva A, Fernandes RP, Araujo MP, Carvalho JP, Carvalho FM, et al. Single-site robotic radical hysterectomy and sentinel lymphnode biopsy in cervical cancer: a case report. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017;39:35–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1597752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markman M. Chemoradiation in the management of cervix cancer: current status and future directions. Oncology. 2013;84:246–250. doi: 10.1159/000346804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loizzi V, Cormio G, Vicino M, Selvaggi L. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy: an alternative option of treatment for locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;65:96–103. doi: 10.1159/000108600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benedetti Panici P, Bellati F, Pastore M, Manci N, Musella A, Pauselli S, et al. An update in neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:S20–S22. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleming ND, Ramirez PT. Robotic surgery in gynecologic oncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:547–553. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328354e572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vizza E, Corrado G, Zanagnolo V, Tomaselli T, Cutillo G, Mancini E, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by robotic radical hysterectomy in locally advanced cervical cancer: a multi-institution study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corrado G, Mereu L, Bogliolo S, Cela V, Freschi L, Carlin R, et al. Robotic single site staging in endometrial cancer: a multi-institution study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1506–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benito V, Carballo S, Silva P, Esparza M, Arencibia O, Federico M, et al. Should the presence of metastatic para-aortic lymph nodes in locally advanced cervical cancer lead to more aggressive treatment strategies? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]