Abstract

Background

Major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are among the most commonly diagnosed mental illnesses in Canada; both are associated with a high societal and economic burden. Treatment for major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder consists of pharmacological and psychological interventions. Three commonly used psychological interventions are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and supportive therapy. The objectives of this report were to assess the effectiveness and safety of these types of therapy for the treatment of adults with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder, to assess the cost-effectiveness of structured psychotherapy (CBT or interpersonal therapy), to calculate the budget impact of publicly funding structured psychotherapy, and to gain a greater understanding of the experiences of people with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder.

Methods

We performed a literature search on October 27, 2016, for systematic reviews that compared CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy with usual care, waitlist control, or pharmacotherapy in adult outpatients with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder. We developed an individual-level state-transition probabilistic model for a cohort of adult outpatients aged 18 to 75 years with a primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder to determine the cost-effectiveness of individual or group CBT (as a representative form of structured psychotherapy) versus usual care. We also estimated the 5-year budget impact of publicly funding structured psychotherapy in Ontario. Finally, we interviewed people with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder to better understand the impact of their condition on their daily lives and their experience with different treatment options, including psychotherapy.

Results

Interpersonal therapy compared with usual care reduced posttreatment major depressive disorder scores (standardized mean difference [SMD]: 0.24, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.47 to −0.02) and reduced relapse/recurrence in patients with major depressive disorder (relative risk [RR]: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.27–0.63). Supportive therapy compared with usual care improved major depressive disorder scores (SMD: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.45–0.72) and increased posttreatment recovery (odds ratio [OR]: 2.71, 95% CI: 1.19–6.16) in patients with major depressive disorder. CBT compared with usual care increased response (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.11–2.26) and recovery (OR: 3.42, 95% CI: 1.98–5.93) in patients with major depressive disorder and decreased relapse/recurrence (RR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.65–0.87]). For patients with generalized anxiety disorder, CBT improved symptoms posttreatment (SMD: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.67–0.93), improved clinical response posttreatment (RR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.55–0.74), and improved quality-of-life scores (SMD: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.06–0.82). There was a significant difference in posttreatment recovery (OR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.11–3.54) and mean major depressive disorder symptom scores (weighted mean difference: −3.07, 95% CI: −4.69 to −1.45) for patients who received individual versus group CBT. Details about the providers of psychotherapy were rarely reported in the systematic reviews we examined.

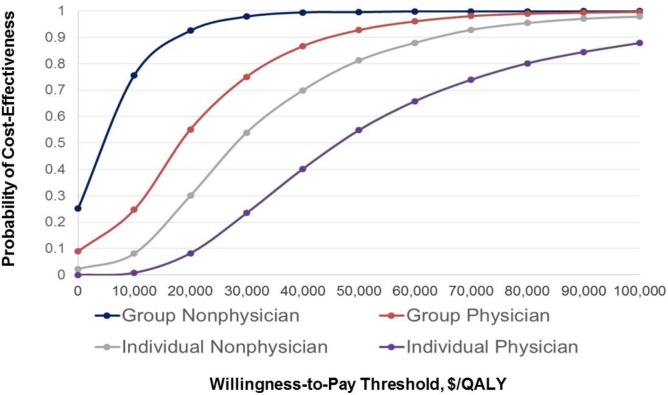

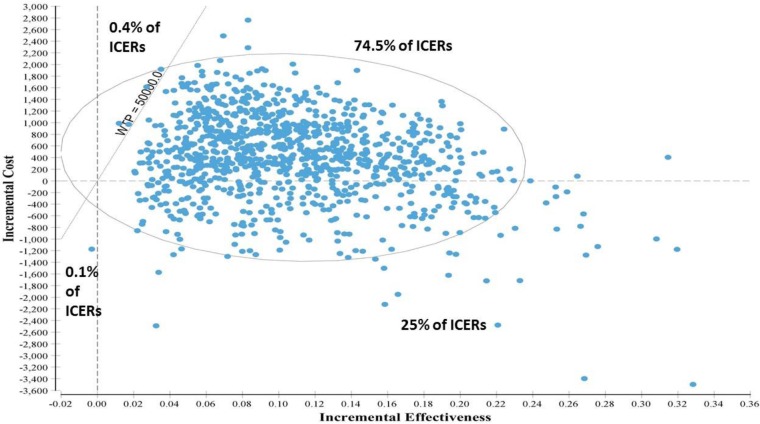

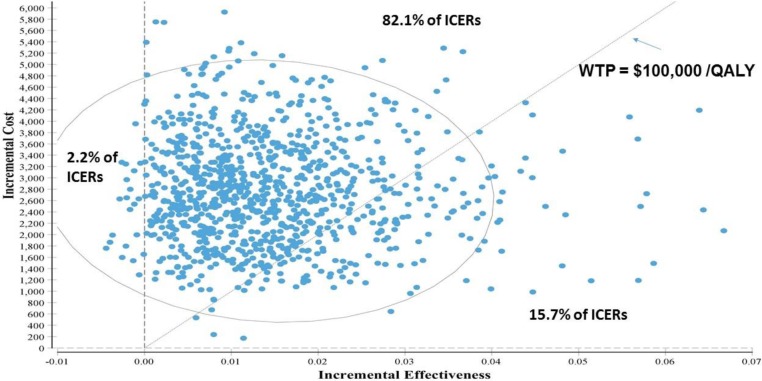

In the base case probabilistic cost–utility analysis, compared with usual care, both group and individual CBT were associated with increased survival: 0.11 quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) (95% credible interval [CrI]: 0.03–0.22) and 0.12 QALYs (95% CrI: 0.03–0.25), respectively.

Group CBT provided by nonphysicians was associated with the smallest increase in discounted costs: $401 (95% CrI: $1,177 to 1,665). Group CBT provided by physicians, individual CBT provided by nonphysicians, and individual CBT provided by physicians were associated with the incremental costs of $1,805 (95% CrI: 65–3,516), $3,168 (95% CrI: 889–5,624), and $5,311 (95% CrI: 2,539–8,938), respectively. The corresponding incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was lowest for group CBT provided by nonphysicians ($3,715/QALY gained) and highest for individual CBT provided by physicians ($43,443/QALY gained). In the analysis that ranked best strategies, individual CBT versus group CBT provided by nonphysicians yielded an ICER of $192,618 per QALY. The probability of group CBT provided by nonphysicians being cost-effective versus usual care was greater than 95% for all willingness-to-pay thresholds over $20,000 per QALY and was around 88% for individual CBT provided by physicians at a threshold of $100,000 per QALY.

We estimated that adding structured psychotherapy to usual care over the next 5 years would result in a net budget impact of $68 million to $529 million, depending on a range of factors. We also estimated that to provide structured psychotherapy to all adults with major depressive disorder (alone or combined with generalized anxiety disorder) in Ontario by 2021, an estimated 500 therapists would be needed to provide group therapy, and 2,934 therapists would be needed to provide individual therapy.

People with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder with whom we spoke reported finding psychotherapy effective, but they also reported experiencing a large number of barriers that prevented them from finding effective psychotherapy in a timely manner. Participants reported wanting more freedom to choose the type of psychotherapy they received.

Conclusions

Compared with usual care, treatment with CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy significantly reduces depression symptoms posttreatment. CBT significantly reduces anxiety symptoms posttreatment in patients with generalized anxiety disorder.

Compared with usual care, treatment with structured psychotherapy (CBT or interpersonal therapy) represents good value for money for adults with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder. The most affordable option is group structured psychotherapy provided by nonphysicians, with the selective use of individual structured psychotherapy provided by nonphysicians or physicians for those who would benefit most from it (i.e., patients who are not engaging well with or adhering to group therapy).

OBJECTIVE

This health technology assessment looked at the effectiveness, safety, cost-effectiveness, budget impact, and patient experiences of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and supportive therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder to determine whether these therapies should be publicly funded.

BACKGROUND

Health Condition

Major depressive disorder is the second largest health care problem worldwide in terms of illness-induced disability.1 The essential feature of major depressive disorder is the occurrence of one or more major depressive episodes. Major depressive episodes are defined as periods lasting at least 2 weeks characterized by depressed mood, most of the day, nearly every day, and/or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities.2 To receive a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, within the same 2-week period a person must experience 5 or more symptoms from the criteria for a major depressive episode as described in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).3

Generalized anxiety disorder is a chronic (constantly recurring) anxiety disorder characterized by persistent, excessive, and difficult-to-control worry that may be accompanied by several psychic (mental) symptoms and somatic (bodily) symptoms.4 It is associated with high rates of comorbidity (having more than one condition at a time), and 68% of people with generalized anxiety disorder report having at least one other psychiatric illness (usually depression, another anxiety disorder, or a substance use disorder).4

The current classification of depressive and anxiety disorders is based on the DSM-5 or the tenth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders.5

Clinical Need and Target Population

The lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder in Canada is 10.8%; annual and 1-month prevalence estimates are 4.0% and 1.3%, respectively.2 Depression affects occupational functioning both through absenteeism and through loss of productivity while attending work when unwell.2 While occupational impairment receives much attention, depression also negatively affect people's ability to perform personal activities, such as parenting and housekeeping. A study in the United States found that people with major depressive disorder were able to perform better at work than in their personal activities.6

Treatment for acute major depressive disorder (during the first 3 months after diagnosis) often consists of pharmacological interventions (medications including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants) and psychological interventions (talk therapies). The prescribing of antidepressant medications has increased over the last 20 years, mainly owing to the development of a new type of antidepressant medication called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, as well as other newer agents.7 While antidepressants continue to be the mainstay of treatment for major depressive disorder, adherence rates remain low in part because of patients' concerns about side effects and possible dependency. In addition, surveys have demonstrated patients' preference for psychological interventions over treatment with antidepressants.7 Therefore, psychological therapies can provide an alternative or additional intervention for major depressive disorder.7

Major depressive disorder is both chronic (lasting 3 months or more) and episodic (consisting of separate episodes) in nature. It consists of initial phases (i.e., the acute and continuation phases, each lasting approximately 3 months) and a maintenance phase (lasting approximately 6 to 24 months, with an average 9 to 12 months).2,8–10 The aim of treatment in the acute and continuation phases is the remission (reduction or elimination) of symptoms and the restoration of psychosocial functioning (a return to the level of psychological and social functioning experienced before the onset of major depressive disorder).2 The aim of treatment in the maintenance phase is to prevent symptoms from recurring.2

In Canada, the 1-year prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in the general population is about 1% to 3%, and the lifetime prevalence is about 6%.4 Patients with generalized anxiety disorder may experience multiple episodes of the disease over their lifetime, and these episodes may be associated with a multitude of disabilities affecting work, education, and social interactions.4

The primary treatment for generalized anxiety disorder consists of medications (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, anxiolytics, and other agents).4 Antidepressants are the first-line treatment (the first type of treatment tried) and have the additional benefit of treating ruminative worry (persistent negative thoughts) and any coexisting depressive symptoms.4 Benzodiazepines, which have a sedative and anti-anxiety effect, were used extensively in the past; however, owing to the potential for developing tolerance and dependence with prolonged use, most guidelines now recommend that for generalized anxiety disorder, benzodiazepines be prescribed for no longer than 2 to 4 weeks.4

As a result of patients' concerns about side effects, psychotherapy is a treatment option that may be considered either as an alternative or additional intervention for generalized anxiety disorder.11

Health Intervention Under Review

Three common types of psychotherapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and supportive therapy.12

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists defines structured psychotherapy as “the treatment of mental or emotional illness by using defined (often manualized) psychological techniques, pre-planned with clear goals and employed within a specific timeframe.”13 According to the College, patients must be seen by their treatment provider, either individually or in a small group, on at least a monthly basis.13 CBT and interpersonal therapy are considered structured psychotherapies, but supportive therapy is not.13

Cognitive behavioural therapy focuses on helping patients become aware of how certain negative automatic thoughts, attitudes, expectations, and beliefs contribute to feelings of sadness and anxiety.12 Patients learn how these thinking patterns, which may have developed in the past to deal with difficult or painful experiences, can be identified and changed to reduce unhappiness.12

Interpersonal therapy focuses on identifying and resolving problems in establishing and maintaining satisfying relationships.12 Such problems may include dealing with loss, life changes, conflicts, and increasing ease in social situations.12

Supportive therapy (also called nondirective supportive therapy) is typically an unstructured therapy that relies on the basic interpersonal skills of the therapist, such as reflection, empathic listening, and encouragement. It has been defined as a psychological treatment in which therapists do not engage in any therapeutic strategy other than active listening and offering support, focusing on patients' problems and concerns.14 It focuses more on current problems rather than long-term difficulties.12 The overall goal is to reduce patients' discomfort level and help them cope with their current circumstances.12,14

Ontario Context

In Ontario, the delivery of psychotherapy from a psychiatrist or other physician trained in psychotherapy is publicly funded. Services provided by other regulated (i.e., registered), trained health care professionals (e.g., nurses, occupational therapists, psychologists, psychotherapists, and social workers) may be free to patients if the services are offered in government-funded hospitals, clinics, or agencies.12 However, many free services have long wait lists. Other free services include employee assistance programs, community clinics, support groups, distress lines, and drop-in centres.

Therapy provided by registered psychologists or psychotherapists in private practice is not publicly funded. However, the fees may be covered by private insurance or workplace coverage, although such private or workplace plans may not cover the full amount or may provide coverage for only certain types of therapist.12

Status in the United States

In the United States, the Medicare program covers outpatient mental health services and visits with the following professionals15:

Psychiatrist or other physician

Clinical psychologist

Clinical social worker

Clinical nurse specialist

Nurse practitioner

Physician assistant

Medicare covers counselling or therapy only when delivered by a health care professional who accepts assignment, which is an agreement by a health care professional to (a) be paid directly by Medicare; (b) accept the payment amount that Medicare approves for the service; and (c) not bill the patient for more than the fee of the Medicare deductible and coinsurance.15

There are caveats around the specific amount a patient is required to pay for treatment depending on several factors, such as the following15:

Other insurance the patient may have

How much the health care professional charges

Whether the provider accepts assignment

The type of facility in which treatment is provided

The location where the patient receives treatment

Health care professionals may recommend a patient receive treatment more often than what Medicare will cover.15 Or, they may recommend services that Medicare does not cover. In such cases, the patient may have to pay some or all of the treatment costs.15

CLINICAL EVIDENCE

Research Questions

What are the effectiveness and safety of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy, and supportive therapy in improving outcomes for adult patients with major depressive disorder and adult patients with generalized anxiety disorder?

What are the effectiveness and safety of individual versus group therapy?

What are the effectiveness and safety of psychotherapy versus no treatment or waitlist control?

What are the effectiveness and safety of psychotherapy with and without pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy only?

What are the effectiveness and safety of psychotherapy provided by physician versus nonphysician providers?

Methods

Research questions are developed by Health Quality Ontario in consultation with experts, end users, and/or applicants in the topic area. Our methodological approaches align with Health Quality Ontario's Health Technology Assessments Methods and Process Guide.16

Literature Search

We performed a literature search on October 27, 2016, to retrieve studies published from January 1, 2000, until the search date. We used the Ovid interface to search the following databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Embase, Health Technology Assessment, MEDLINE, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED), and PsycINFO. We used the EBSCOhost interface to search the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

Search strategies were developed by medical librarians using controlled vocabulary (e.g., Medical Subject Headings) and relevant keywords. Methodological filters were used to limit retrieval to systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and health technology assessments. The final search strategy was peer-reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist.17 Database auto-alerts were created in CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO and monitored for the duration of the health technology assessment review.

We performed targeted grey literature searching of health technology assessment agency websites and PROSPERO systematic review registry. See Appendix 1 for the literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Literature Screening

A single reviewer reviewed the abstracts, and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, we obtained full-text articles. We also examined reference lists for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

Studies published between January 1, 2000, and October 27, 2016

Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials only

Studies on adult outpatients with major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder who received CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy

Studies that report a definition or diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder (i.e., DSM-3, DSM-4, DSM-5, or ICD-10 criteria or based on other validated diagnostic instruments)

Comparators of usual care, waitlist control, or pharmacotherapy

Exclusion Criteria

Animal and in vitro studies

Studies that are not systematic reviews

Studies on children or adolescents (≤ 18 years of age) or older people (≥ 65 years of age)

Studies that focus on postpartum depression, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, seasonal affective disorder, psychotic disorders, or drug or alcohol dependence-related depression

Studies that examine nontraditional CBT (e.g., mindfulness CBT), telephone-based CBT, computer-based CBT, or Internet-based CBT

Studies where relevant data are unable to be extracted (e.g., results for “psychotherapy” are reported without describing the specific type of psychotherapy, or results for “depressive disorders” or “anxiety disorders” are reported without specific breakdowns for major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder, respectively)

Outcomes of Interest

Remission of depression or anxiety symptoms

Prevention of relapse following successful acute treatment

Response to therapy (e.g., ≥ 50% reduction in symptoms from baseline)

Adverse events

Quality of life

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on study characteristics; risk-of-bias items; and population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and time (PICOT) criteria using a standardized data form. The form collected information about the following:

Source (i.e., citation information, contact details, and study type)

Methods (i.e., study design)

Outcomes (i.e., outcomes measured, number of participants for each outcome, outcome definition and source of information, unit of measurement, upper and lower limits [for scales], and time points at which outcomes were assessed)

Statistical Analysis

This review reports results only from systematic reviews. We did not perform an analysis of primary studies.

Quality of Evidence

We used A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews.18 See Appendix 2 for details of the AMSTAR analysis.

Expert Consultation

In December 2016, we sought expert consultation on the use of CBT, interpersonal therapy, and supportive therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Members of the consultation included health care professionals in the specialty areas of psychology, psychiatry, and family medicine. The role of the expert advisors was to help contextualize the evidence and provide advice on the use of CBT, interpersonal therapy, and supportive therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. However, the statements, conclusions, and views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the consulted experts.

Results

Literature Search

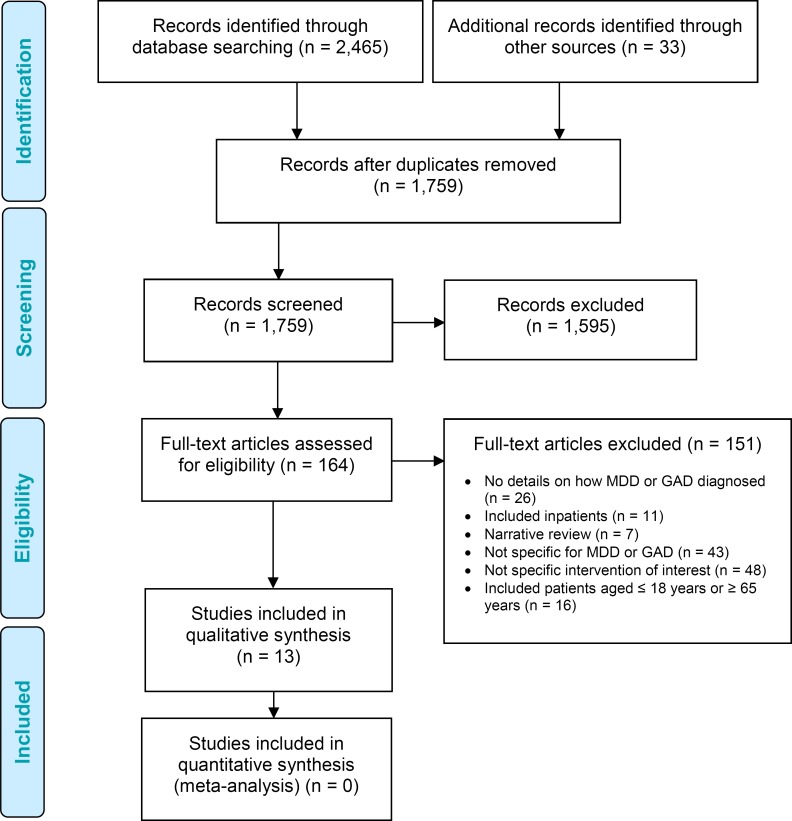

The database and grey literature searches yielded 1,759 citations published between January 1, 2000, and October 27, 2016 (after duplicates removed). We reviewed titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant articles and obtained the full texts of these articles for further assessment. Thirteen systematic reviews met the inclusion criteria. We hand-searched the reference lists of the included studies, and other sources, to identify any additional relevant studies.

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) for the clinical evidence review.

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Clinical Evidence Review.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.19

Abbreviations: GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Compared With Usual Care for Major Depressive Disorder

Depressive Symptoms, Treatment Response, and Remission

Three systematic reviews reported results for symptoms of major depressive disorder after patients received CBT compared with usual care.20–22

In 2016, Cuijpers et al systematically reviewed the effectiveness of CBT for the acute treatment of major depressive disorder compared with control (wait list, usual care, or pill placebo) (63 randomized controlled trials, number of patients not reported).20 Overall, CBT significantly reduced mean major depressive disorder symptom scores for patients who had undergone CBT compared with control (SMD: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.64–0.87]).20

Cuijpers et al reported that 11 of the 63 studies were rated high quality, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.20 Of note, the authors analyzed for publication bias and estimated that approximately 14% of major depressive disorder studies were missing from publication; thus, the pooled effect size dropped from an SMD of 0.75 to an SMD of 0.65 (95% CI: 0.53–0.78).20

No studies reviewed by Cuijpers et al reported on the providers of CBT.20

Linde et al conducted a meta-analysis to determine the effectiveness of psychotherapy compared with usual care or placebo in primary care patients with major depressive disorder.21 The authors conducted an analysis of 7 randomized controlled trials (N = 518) for face-to-face CBT. The meta-analysis included 5 studies23–27 that were also included in the systematic review by Cuijpers et al.20 The standardized mean difference for posttreatment major depressive disorder symptom scores compared with control was statistically significant, favouring CBT: −0.30 (95% CI: −0.48 to −0.13).

Linde et al also reported a statistically significant pooled estimate for response (defined as a ≥ 50% score reduction on a depression scale) favouring CBT and a statistically nonsignificant pooled estimate for remission (defined as a symptom score below a fixed threshold) for CBT compared with usual care (OR: 1.58, 95% CI: 1.11–2.26, and OR: 1.49, 95% CI: 0.90–2.46, respectively).21

The authors rated the overall quality of the trials in the systematic review as low, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias criteria.21 The reporting of intervention details for usual care and for co-interventions (e.g., pharmacotherapy) in the groups receiving psychotherapy was often insufficient.21

The providers of treatment in the included studies varied and included counsellors, nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, psychotherapists, and therapists.21

Churchill et al22 systematically reviewed psychotherapies for the treatment of major depressive disorder and performed an analysis for CBT compared with usual care. Of the 20 studies included in the analysis, 424,25,27,28 were also included in the more recent systematic review by Cuijpers et al.20 Overall, there was a significant difference in posttreatment recovery (12 studies, N = 654; OR: 3.42, 95% CI: 1.98–5.93).22 Posttreatment recovery was defined as patients no longer being deemed to have a clinically meaningful level of depression, as indicated by a score of less than 10 on the Beck Depression Inventory or less than 6 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. The authors also found a significant difference in mean major depressive disorder symptom scores for patients who received CBT versus usual care (20 studies, N = 748; SMD: −1.0, 95% CI: −1.35 to −0.64).22

Churchill et al also reported results for individual versus group CBT.22 Overall, there was a significant difference in posttreatment recovery (6 studies, N = 234; OR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.11–3.54) and mean major depressive disorder symptom scores (8 studies, N = 283; weighted mean difference [WMD]: −3.07, 95% CI: −4.69 to −1.45]) for patients who received individual versus group CBT.22

The authors rated the overall quality of evidence as low, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool, owing to low scores on internal validity and inadequate reporting of methodology.22

No studies reviewed by Churchill et al reported on the providers of CBT.22

Relapse

Three systematic reviews reported results for relapse of major depressive disorder after patients had received treatment with CBT versus usual care.29–31

Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al systematically reviewed the effectiveness of psychological interventions compared with usual care or antidepressant drugs in reducing relapse or recurrence rates of patients in remission.29 Usual care was defined as routine clinical management, assessment only, no treatment, or wait list. Relapse and recurrence were defined by the primary study investigators; examples include surpassing a threshold score on a depression scale and demonstrating a change in diagnostic depression status based on clinical assessment. The authors also conducted a subset analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials (N = 529) for CBT.29

CBT significantly reduced the risk of relapse or recurrence compared with usual care (RR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.65–0.87) but not compared with antidepressant drugs (RR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.61–1.02).29

The authors rated the overall quality of evidence as low, according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria, owing to varying definitions of remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence in the primary studies.29

No studies reviewed by Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al reported on the providers of CBT.29

Clarke et al conducted a meta-analysis to determine the effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions compared with control (defined as usual care, clinical management, or antidepressant drugs) in people who had recovered from major depressive disorder (defined as being in full or partial remission).30 The authors also conducted a subset analysis of nine randomized controlled trials (N = 853) for CBT. The systematic review included three randomized controlled trials32–34 also included in the meta-analysis by Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al.29

At 12 and 24 months, the risk of developing a new episode of major depressive disorder was significantly reduced in patients who had received CBT compared with control (RR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.64–0.89, and RR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.57–0.91, respectively.30

The authors rated the overall quality of evidence as low, based on the GRADE criteria.30

No studies reviewed by Clarke et al reported on the providers of CBT.30

Guidi et al31 systematically reviewed the effectiveness of CBT compared with usual care or clinical management in the treatment of people with major depressive disorder who had successfully responded to a previous course of treatment with antidepressant drugs. (The difference between usual care and clinical management was not described.) Effectiveness was assessed in terms of relapse or recurrence rates of major depressive disorder. All 13 studies (N = 1,410) reviewed by Guidi et al31 were also included in the reviews by Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al29 and/or Clarke et al.30 The overall pooled risk ratio for relapse or recurrence for CBT compared with usual care or clinical management was statistically significant, favouring CBT (0.78; 95% CI: 0.67–0.91).

The authors reported that the methodological quality of the studies included in their meta-analysis was high; however, they did not report their method of rating study quality.31

No studies reviewed by Guidi et al reported on the providers of CBT.31

Adverse Events

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Quality of Life

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy With and Without Pharmacotherapy Compared With Pharmacotherapy Only for Major Depressive Disorder

Depressive Symptoms, Treatment Response, and Remission

Three systematic reviews reported results for treatment response after patients received CBT and pharmacotherapy compared with pharmacotherapy only for the treatment of major depressive disorder.35–37

Karyotaki et al systematically reviewed the effectiveness (as measured by response rate) of combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy compared with psychotherapy only or pharmacotherapy only in both the acute and maintenance treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. The authors also conducted a subset analysis for CBT.35

For acute-phase treatment, there was no significant difference in response rate for combined CBT and pharmacotherapy compared with CBT only at up to 6 months postrandomization (5 comparisons, number of patients not reported; OR: 1.51, 95% CI: 0.79–2.86) and up to 1 year postrandomization (4 comparisons, number of patients not reported; OR: 1.48, 95% CI: 0.59–3.71).35 However, there was a significant difference in response rate when the combination of CBT and pharmacotherapy was compared with pharmacotherapy only at up to 6 months (6 comparisons, number of patients not reported; OR: 3.02, 95% CI: 1.74–5.25) and up to 1 year postrandomization (4 comparisons, number of patients not reported; OR: 3.37, 95% CI: 1.38–8.21).35

For maintenance-phase treatment, no data were available for combined CBT and pharmacotherapy versus CBT only.35 There was a significant difference in response rate when the combination of CBT and pharmacotherapy was compared with pharmacotherapy only at up to 6 months postrandomization (4 comparisons, number of patients not reported; OR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.19–2.70).35 No data were available for response rates at more than 1 year postrandomization.35

The authors rated the overall quality of evidence as low, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.35

No studies reviewed by Karyotaki et al reported on the providers of CBT.35

Amick et al meta-analyzed studies to determine the effectiveness (as measured by the rate of response and remission) of second-generation antidepressants (the most commonly prescribed class of antidepressants, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin– norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) only versus CBT only and second-generation antidepressants only versus a combination of second-generation antidepressants and CBT for the treatment of major depressive disorder.36 Response was defined as a decrease in depressive severity of equal to or greater than 50%, and remission was defined by the authors of the individual trials.36

For second-generation antidepressants only compared with CBT only, there were no significant differences in remission (3 trials; risk ratio: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.73–1.32), response (5 trials; risk ratio: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.77–1.07), or overall treatment discontinuation (4 trials; risk ratio: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.55–1.81).36

For second-generation antidepressants only compared with a combination of second-generation antidepressants and CBT, the authors found no significant differences for remission (1 trial; risk ratio: 1.06, 95% CI: 0.82–1.38); response (1 trial; risk ratio: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.85–1.26); or overall treatment discontinuation (1 trial; risk ratio: 0.77, 95% CI: 0.37–1.60).36

The authors rated the overall strength of evidence as low, based on methods guidance from the Evidence-Based Practice Centers Program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.36

The treatment providers in the studies reviewed by Amick et al varied in terms of provider type, training, and experience.36

Cuijpers et al systematically reviewed the effectiveness of acute-phase CBT without any subsequent continuation treatment compared with pharmacotherapy (that was either continued or discontinued) in patients with major depressive disorder.37 The primary outcome was the number of patients who responded to treatment and remained well (defined as treatment response maintained across 6 to 18 months of follow-up).37 Overall, the authors identified 9 studies (N = 506; for CBT, n = 271; for pharmacotherapy, n = 235).37

For acute-phase CBT (without continuation treatment) compared with acute-phase pharmacotherapy with continued pharmacotherapy during follow-up, there was no significant difference in 1-year outcomes (5 studies; OR: 1.62, 95% CI: 0.97–2.72).37

For acute-phase CBT (without continuation treatment) compared with acute-phase pharmacotherapy that was discontinued during follow-up, there was a significant difference in 1-year outcomes, favouring CBT (8 studies; OR: 2.61, 95% CI: 1.58–4.31).37

The authors rated the overall quality of evidence as high, according to the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.37

No studies reviewed by Cuijpers et al reported on the providers of CBT.37

Relapse

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Adverse Events

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Quality of Life

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Compared With Usual Care for Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Anxiety Symptoms, Treatment Response, and Remission

Three systematic reviews reported results for treatment response after patients received CBT compared with usual care for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder.11,20,38

In 2016, Cuijpers et al systematically reviewed the effectiveness of CBT (as measured by reduction in anxiety symptoms) compared with control (wait list, usual care, or pill placebo) for the acute treatment of patients with anxiety disorders.20 A subset analysis was conducted for generalized anxiety disorder (31 studies, number of patients not reported). Overall, mean generalized anxiety disorder symptom scores were significantly reduced by CBT compared with control (SMD: 0.80, 95% CI: 0.67–0.93).20

The authors rated 9 of the 31 studies as high quality, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.20 Of note, the authors analyzed for publication bias, and they estimated that about one-quarter of generalized anxiety disorder studies were missing. After adjusting for these missing studies, the effect size dropped from an SMD of 0.80 to an SMD of 0.59 (95% CI: 0.44–0.75). However, this result did not change the statistical significance of the finding.20

No studies reviewed by Cuijpers et al reported on the providers of CBT.20

In 2014, Cuijpers et al meta-analyzed studies to determine the effectiveness of psychotherapies versus control (wait list, usual care, or pill placebo) for people with generalized anxiety disorder.38 The authors also conducted a subset analysis for CBT (28 comparisons, number of patients not reported). We determined that there was overlap between the studies included in this 2014 analysis and those included in the systematic review by Cuijpers et al in 2016 (described above)20; however, the studies within the CBT subset comparison reported in the 2016 systematic review were unique to that publication.38 Overall, there was no significant difference in mean generalized anxiety disorder symptom scores posttreatment for people treated with CBT compared with control (SMD: 0.90, 95% CI: 0.75–1.05).38

The authors rated the overall quality of the studies included in the 2014 systematic review as low, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.38 The authors commented that the overall quality of the interventions also varied across studies (e.g., not all psychotherapy providers reported using a standard manual, and limited information was provided on treatment components, including those of CBT, and adherence to treatment manuals).38

The authors further stated that the literature on psychotherapy studies for generalized anxiety disorder differs markedly from that for major depressive disorder, in which the same standard treatment manual is used across many studies.38

The authors did not report publication bias for the subset analysis.

No studies reviewed by Cuijpers et al reported on the providers of CBT.38

In 2007, Hunot et al systematically reviewed the effectiveness of CBT compared with usual care or wait list for the treatment of patients with generalized anxiety disorder.11 Primary outcomes included clinical response (8 studies, N = 334) and reduction in generalized anxiety disorder symptoms (12 studies, N = 350) posttreatment.11 There was a significant difference in clinical response and reduction in generalized anxiety disorder symptoms, favouring CBT versus usual care or wait list (RR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.55–0.74, and SMD: −1.00, 95% CI: −1.24 to −0.77], respectively).11 Seven39–45 of the 12 studies included in the outcome of reduction in generalized anxiety disorder symptom response were also included in the meta-analysis by Cuijpers et al.20

The authors also conducted subset analyses for individual CBT (9 studies) and for group CBT (4 studies) compared with usual care or wait list.11 Patients in individual or group CBT achieved clinical response significantly more than patients in usual care or on wait list (RR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.51–0.76, and RR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.54–0.82, respectively).11 Similarly, there was a significant difference in generalized anxiety disorder symptoms, favouring CBT (individual CBT: SMD: −0.98, 95% CI: −1.32 to −0.65; group CBT: SMD: −1.02, 95% CI: −1.35 to −0.69]).11

Hunot et al reported an overall moderate risk of bias for the included studies, according to criteria set out in the Cochrane Handbook.11

The authors reported that the providers of treatment in the studies varied and were described as clinical psychologists; doctoral-, senior-, or advanced-level CBT therapists; “experienced therapists”; or “therapists.”11

Relapse

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Adverse Events

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Quality of Life

Hunot et al reported on posttreatment improvement in quality of life (3 studies, N = 112).11 The difference in quality-of-life mean scores between people who received CBT and those in the treatment-as-usual/waitlist group was significant, in favour of CBT (SMD: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.06–0.82).11

Interpersonal Therapy Compared With Usual Care for Major Depressive Disorder

Depressive Symptoms, Treatment Response, and Remission

Two systematic reviews reported results for a reduction in depressive symptoms after treatment with interpersonal therapy versus usual care.21,46

Jakobsen et al46 conducted a meta-analysis of 4 randomized controlled trials (N = 553) and reported a significant reduction in depression symptoms for patients with acute major depressive disorder treated with interpersonal therapy compared with usual care. This reduction was based on scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory (mean differences: −3.53 [95% CI: −4.91 to −2.16, P < .0001] and −3.09 [95% CI: −5.35 to −0.83, P = .007]). The authors also reported a significant reduction in the number of patients who did not experience remission (defined as a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score < 8) in the interpersonal therapy versus treatment-as-usual group (OR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.24–0.55).46

The authors reported that all trials in the systematic review had a high risk of bias, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias criteria.46

No studies reviewed by Jakobsen et al reported on the providers of interpersonal therapy, and the definition of usual care varied across the studies (e.g., standard care, clinical management).46

Linde et al conducted a meta-analysis to determine the effectiveness of psychotherapy versus usual care or placebo in primary care patients with major depressive disorder.21 The authors also conducted a meta-analysis of 2 randomized controlled trials (N = 305) for interpersonal therapy. One randomized controlled trial47 was also included in the meta-analysis by Jakobsen et al.46

The standardized mean difference for the posttreatment major depressive disorder scores of patients who had undergone interpersonal therapy compared with control was −0.24 (95% CI: −0.47 to −0.02),21 which indicates that interpersonal therapy significantly improved depression symptoms compared with control.

The authors also reported pooled estimates for response (defined as a depression scale score reduction of ≥ 50%) and remission (defined as a symptom score below a fixed threshold) (OR: 1.28 [95% CI: 0.80–2.05] and OR: 1.37 [95% CI: 0.81–2.34], respectively).21 These results indicate that there was no significant difference between interpersonal therapy and usual care in terms of response or remission.

The authors rated the overall quality of evidence as low, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias criteria.21

The providers of treatment in the studies reviewed by Linde et al varied and included counsellors, nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, psychotherapists, and therapists.21 (No distinction between “psychotherapist” and “therapist” was made.) The reporting of intervention details for usual care and co-interventions (e.g., pharmacotherapy) in the groups receiving psychological treatment was often insufficient.21

In 2001, Churchill et al22 conducted a systematic review of psychological treatments compared with usual care for the treatment of major depressive disorder. The authors also conducted a subset analysis of 1 randomized controlled trial47 (N = 185) for interpersonal therapy. Since this single trial was also included in the meta-analyses of Linde et al,21 Biesheuvel-Leliefeld et al,29 and Jakobsen et al,46 details of this study are not discussed here.

Relapse

Two systematic reviews reported results for relapse of major depressive disorder after patients received treatment with interpersonal therapy versus usual care.29,30

Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al systematically reviewed the effectiveness of psychological interventions compared with usual care or antidepressant drugs in reducing relapse or recurrence rates of patients in remission.29 Usual care was defined as routine clinical management, assessment only, no treatment, or wait list. Relapse and recurrence were defined by the primary study investigators; examples include surpassing a threshold score on a depression scale and demonstrating a change in diagnostic depression status based on clinical assessment. The authors also conducted a subset analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials (N = 142) for interpersonal therapy. The systematic review included 1 randomized controlled trial47 also included in the meta-analyses by Jakobsen et al46 and Linde et al.21

Interpersonal therapy significantly reduced the risk of relapse or recurrence compared with usual care (RR: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.27–0.63) but not compared with antidepressant drugs (RR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.50–1.38).29

The authors rated the overall quality of evidence for relapse as low, according to the GRADE criteria, owing to varying definitions of remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence in the primary studies.29

No studies reviewed by Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al reported on the providers of interpersonal therapy.29

Clarke et al conducted a meta-analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials (N = 342) for interpersonal therapy to determine its effectiveness compared with control (defined as usual care, clinical management, or antidepressant drugs) in patients who had recovered from major depressive disorder (defined as being in full or partial remission).30 One randomized controlled trial48 was included in the meta-analysis by Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al.29

At 12 months, the risk of developing a new episode of major depressive disorder was significantly reduced in patients who had received interpersonal therapy compared with control (RR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.65–0.95).30 At 24 months, there was no significant difference between patients who had received interpersonal therapy compared with control in terms of the risk of developing a new episode (RR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.81–1.05).30

The authors rated the overall quality of evidence for relapse as low, according to the GRADE criteria.30

No studies reviewed by Clarke et al reported on the providers of interpersonal therapy.30

Adverse Events

This outcome was rarely reported in the systematic reviews.

Jakobsen et al stated that 149 of the 4 studies included in their meta-analysis reported adverse events. This was a greater tendency for participants in the treatment-as-usual group to be hospitalized after the end of treatment, but this finding was not statistically significant.46

Quality of Life

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Supportive Therapy Compared With Usual Care for Major Depressive Disorder

Depressive Symptoms, Treatment Response, and Remission

We identified 2 systematic reviews that reported results for changes in depressive symptoms after patients had received supportive therapy versus usual care for the treatment of major depressive disorder.14,22

Cuijpers et al conducted a meta-analysis to determine the effectiveness of supportive therapy compared with control (usual care or wait list) (18 studies, N = 899) or pharmacotherapy (4 studies, N = 408) in patients with major depressive disorder.14

Compared with usual care or waitlist control, supportive therapy significantly improved symptoms of depression (SMD: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.45–0.72). However, the authors found no significant difference between supportive therapy and pharmacotherapy (SMD: −0.18, 95% CI: −0.59 to 0.23).14

The authors rated the overall quality of the evidence as low, according to the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.14

The providers of supportive therapy reported in the studies reviewed by Cuijpers et al were diverse and included nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, specialists in counselling, and trained nonspecialists.14

Churchill et al systematically reviewed psychotherapies for the treatment of major depressive disorder and performed an analysis for supportive therapy compared with usual care.22 Of the 4 studies included in this analysis,24,50–52 3 studies24,50,51 were also included in the 2016 systematic review by Cuijpers et al.14 Overall, there was a significant difference in posttreatment recovery (4 studies, N = 118; OR: 2.71, 95% CI: 1.19–6.16]).22 Posttreatment recovery was defined as patients no longer being deemed to have a clinically meaningful level of depression, as indicated by a score of less than 10 on the Beck Depression Inventory or less than 6 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. The authors also found a significant reduction in symptoms for patients who had received supportive therapy versus usual care (4 studies, N = 123; SMD: −0.42, 95% CI: −0.78 to −0.06]).22

The authors reported that the overall quality of evidence was low, based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool, owing to low scores on internal validity and inadequate reporting of methodology.22

No studies reviewed by Churchill et al reported on the providers of supportive therapy.22

Adverse Events

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

Quality of Life

This outcome was not reported in the systematic reviews.

A full summary of the study characteristics and results of all systematic reviews included in this health technology assessment can be found in Appendix 2, Table A2. A summary of the main results is presented in Tables 1a, 1b, and 1c.

Table 1a:

Summary of Results: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

| Indication | Results |

|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder | |

| Symptoms, Treatment Response, Remission |

CBT vs. control (usual care, clinical management, or wait list) Cuijpers et al20

Linde et al21(primary care patients)

Churchill et al22

|

|

ADM + CBT vs. CBT only (acute treatment) Karyotaki et al35

|

|

|

ADM + CBT vs. ADM only (acute treatment) Karyotaki et al35

|

|

|

ADM + CBT vs. ADM only (maintenance treatment) Karyotaki et al35

|

|

|

SGA vs. CBT Amick et al36

|

|

|

SGA only vs. SGA + CBT Amick et al36

Acute CBT (without continuation CBT) vs. acute ADM (with continued ADM) Cuijpers et al37

|

|

|

Acute CBT (without continuation CBT) vs. acute ADM (discontinued at follow-up) Cuijpers et al37

|

|

| Relapse/Recurrence |

CBT vs control (usual care, clinical management, or wait list) Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al29

Clarke et al30

Guidi et al31

|

| Adverse Events | Not reported |

| Quality of Life | Not reported |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | |

| Symptoms, Treatment Response, Remission |

Compared with control (usual care, clinical management, or wait list) Cuijpers et al20

Cuijpers et al53

Hunot et al11

|

| Relapse/Recurrence | Not reported |

| Adverse Events | Not reported |

| Quality of Life | Compared with control (usual care, clinical management, or wait list) |

| Hunot et al11 | |

| Improvement in quality-of-life score: SMD = 0.44 (95% CI: 0.06–0.82) | |

Abbreviations: ADM, antidepressant medication; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CI, confidence interval; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio; SGA, second-generation antidepressant; SMD, standardized mean difference; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Defined by Churchill et al as no longer having a clinically meaningful level of depression (as measured by a BDI score < 10 or an HDRS score < 6).22

Table 1b:

Summary of Results: Interpersonal Therapy

| Indication | Results |

|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder | |

| Symptoms, Treatment Response, Remission |

Compared with control (usual care, clinical management, or wait list) Jakobsen et al46

Linde et al21(primary care patients)

|

| Relapse/Recurrence |

Biescheuvel-Leliefeld et al29

Clarke et al30

|

| Adverse Events | Not reported |

| Quality of Life | Not reported |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | |

| Symptoms, Treatment Response, Remission | Not reported |

| Relapse/Recurrence | Not reported |

| Adverse Events | Not reported |

| Quality of Life | Not reported |

Abbreviations: ADM, antidepressant medication; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CI, confidence interval; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IPT, interpersonal therapy; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Table 1c:

Summary of Results: Supportive Therapy

| Indication | Results |

|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder | |

| Symptoms, Treatment Response, Remission |

Cuijpers et al14

Churchill et al22

|

| Relapse/Recurrence | Not reported |

| Adverse Events | Not reported |

| Quality of Life | Not reported |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | |

| Symptoms, Treatment Response, Remission | Not reported |

| Relapse/Recurrence | Not reported |

| Adverse Events | Not reported |

| Quality of Life | Not reported |

Abbreviations: BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CI, confidence interval; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Defined by Churchill et al as no longer having a clinically meaningful level of depression (as measured by a BDI score < 10 or an HDRS score < 6).22

Discussion

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Compared With Usual Care

Three meta-analyses of CBT for the treatment of major depressive disorder indicated that CBT significantly reduced depression symptoms posttreatment compared with usual care.20–22

Three meta-analyses reported results for posttreatment relapse of major depressive disorder following treatment with CBT versus usual care.29–31 Overall, the 3 reviews concluded that CBT significantly reduced the risk of relapse or recurrence compared with usual care.29–31

Two meta-analyses of CBT for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder indicated that CBT significantly reduced anxiety symptoms posttreatment compared with usual care.11,20

None of the systematic reviews reported on adverse events.

One systematic review of CBT for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder assessed quality of life.11 The difference in mean quality-of-life scores between patients who had received CBT and those who had received usual care was significant, in favour of CBT.11

The overall quality of the evidence within the systematic reviews was generally reported as low. Reasons for this include antidepressants used in control groups being variously described as “treatment as usual” and “clinical management”; varying definitions provided for recovery, recurrence, relapse, and remission; lack of blinding of patients and treatment providers; and several studies excluding from their analyses randomized patients who did not commence treatment or later dropped out.

Cuijpers et al performed a meta-analysis of CBT versus usual care with regard to symptom reduction.20 They evaluated the evidence for publication bias and estimated that approximately 14% of major depressive disorder studies and 25% of generalized anxiety disorder studies were missing from their meta-analysis; however, they reported that this did not change the statistical significance of their pooled summary estimates.20 Driessen et al investigated publication bias in the literature on psychological interventions for depression and concluded that the efficacy of psychological interventions in general has been overestimated in the published literature, as it has been for pharmacotherapy.54 The authors stated that both treatments are effective but not to the extent that the published literature would suggest.54 As a result, Driessen et al suggest that funding agencies and journals should archive both original protocols and raw data from studies to allow for the detection and correction of outcome-reporting bias.54

Cuijpers et al commented on the quality of CBT in generalized anxiety disorder studies, finding that not all psychotherapy providers reported using a standard manual and that limited information was provided on treatment components, including those of CBT, and adherence to treatment manuals.38 The authors further stated that the literature on psychotherapy studies for generalized anxiety disorder differs markedly from that for major depressive disorder, in which the same standard treatment manual is used across many studies.38

The systematic reviews rarely reported details about the providers of CBT; in those that did, there was variation in provider type.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy With and Without Pharmacotherapy Compared With Pharmacotherapy Only

For the acute treatment of major depressive disorder, Karyotaki et al reported no significant difference in response rates for combined CBT and antidepressants compared with CBT only at up to 6 months and up to 1 year postrandomization.35

Amick et al systematically reviewed second-generation antidepressants compared with CBT for the treatment of major depressive disorder and found no significant difference in response or remission rates.36

Cuijpers et al compared acute-phase CBT (without continuation treatment) with acute-phase pharmacotherapy (with pharmacotherapy continued during follow-up) in patients with major depressive disorder and found no significant difference in outcome (as measured by the number of patients who responded to treatment and remained well) at a 1-year follow-up.37 However, when acute-phase CBT (without continuation treatment) was compared with acute-phase pharmacotherapy that was discontinued during follow-up, there was a significant difference in 1-year outcomes, favouring CBT.37

The systematic reviews did not report on adverse events or quality of life.

The overall quality of the evidence within 2 systematic reviews was generally reported as low.35,36 However, Cuijpers et al considered the overall quality of the evidence they reviewed to be “relatively high” compared with the quality of studies on psychotherapy for adult depression in general.37

Details about treatment providers were rarely reported in these systematic reviews.

Interpersonal Therapy

Two meta-analyses of interpersonal therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder indicated that interpersonal therapy significantly reduced depression symptoms posttreatment compared with usual care.21,46

The overall quality of the evidence within the systematic reviews was consistently reported as low. Of note, the feasibility of providing high-quality evidence in psychological studies is difficult, and the issues affecting quality are not easily addressed within the context of randomized controlled trials.22 For example, individual therapist characteristics cannot be controlled for, nor can the nature of the therapeutic encounter be measured with absolute precision.22

The systematic reviews rarely reported on treatment providers.

We identified no systematic reviews of interpersonal therapy for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder that matched our inclusion criteria.

Supportive Therapy

Two meta-analyses of supportive therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder concluded that supportive therapy significantly reduced symptoms of major depressive disorder posttreatment compared with usual care. Cuijpers et al found no significant difference between supportive therapy and pharmacotherapy in reducing symptoms of depression in patients with major depressive disorder.14 Churchill et al found a significant difference in posttreatment recovery favouring supportive therapy versus usual care.22

Adverse events and quality of life were not reported in the systematic reviews.

As with interpersonal therapy, the overall quality of the evidence within the systematic reviews was consistently reported as low, based on similar reasons to those discussed for interpersonal therapy, as well as low scores on internal validity and inadequate reporting of methodology.22

The systematic reviews rarely reported on treatment providers.

We identified no systematic reviews of supportive therapy for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder that matched our inclusion criteria.

Limitations to This Systematic Review

The following limitations apply to our systematic review:

Primary studies were not included in this analysis; we included only systematic reviews.

Interventions were compared with usual care or pharmacotherapy. Psychological interventions were not directly compared with each other

We did not include systematic reviews on long-distance or computer/Internet-based psychotherapy

The patient population was restricted to adults; we excluded pediatric and geriatric populations

We considered only major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder; we did not examine other types of depression or anxiety

Conclusions

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Interpersonal Therapy, or Supportive Therapy Compared With Usual Care for Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Treatment with CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy reduces symptoms of major depressive disorder and increases response/recovery posttreatment

CBT and interpersonal therapy significantly reduce the risk of relapse/recurrence of major depressive disorder

Individual CBT significantly improves posttreatment recovery from major depressive disorder compared with group CBT

CBT significantly reduces symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder and increases response posttreatment

CBT significantly improves quality-of-life scores in people with generalized anxiety disorder

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy With and Without Pharmacotherapy Compared With Pharmacotherapy Only for Major Depressive Disorder

Combined therapy (CBT with pharmacotherapy) significantly improves treatment response compared with pharmacotherapy only

CBT significantly improves treatment response compared with pharmacotherapy only following termination of both acute interventions

Details About Psychotherapy Providers

Of the systematic reviews we examined, 3 reported on provider type; in these reviews, a diverse range of providers was described

ECONOMIC EVIDENCE

Research Questions

What is the cost-effectiveness of a psychological treatment (i.e., CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy) provided as the only therapy or combined with pharmacotherapy for the management of adults with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder?

What is the cost-effectiveness of different outpatient models of care for providing in-person psychological treatments in the management of adults with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder?

Methods

Literature Search

We performed an economic literature search on October 28, 2016, for studies published from January 1, 2000, until the search date. To retrieve relevant studies, we used the clinical search strategy with an economic filter.

Database auto-alerts were created in CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO and monitored for the duration of the health technology assessment review. We performed targeted grey literature searching of health technology assessment agency websites and clinical trial registries. See Clinical Evidence, Literature Search (p. 11), for further details on methods used.

Finally, we reviewed the reference lists of the included economic literature for any additional relevant studies not identified through the systematic search.

The literature search strategies, including all search terms, are described in Appendix 1.

Literature Screening

A single reviewer screened titles and abstracts, and, for those studies meeting the inclusion criteria, we obtained full-text articles. For the full-text citations that did not meet the inclusion criteria, we recorded reasons for exclusion.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language, individual-level economic evaluations conducted alongside randomized controlled trials (i.e., trial-based) or economic analyses based on decision analytic models (i.e., model-based)

Studies in adults with major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder indicated for psychotherapy

Studies comparing CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy with other nonpharmacologic therapies or no treatment (e.g., waitlist control)

Studies comparing different models of providing in-person CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy (e.g., group vs. individual therapy, physician vs. nonphysician provider)

Exclusion Criteria

Reviews (systematic and narrative), study protocols, guidelines, conference abstracts, commentaries, letters, and editorials

Economic evaluations of psychotherapy for the treatment of postnatal depression or comorbid depression (i.e., depression coexisting with chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, dementia, diabetes mellitus, or inflammatory bowel disease) or studies conducted in adolescent populations

Economic evaluations of psychotherapies provided via computer-based technologies such as computer programs or Internet-based applications

Economic evaluations comparing collaborative team or stepped-care models with usual care for the treatment of major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder

Economic studies in inpatient adults with treatment-resistant depression (secondary psychiatric care)

Feasibility studies exploring different models of care for the treatment of major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder that do not report economic outcomes

Noncomparative studies reporting the costs of psychotherapies

Cost-of-illness studies

Types of Participants

The population of interest was adults (aged 18 years and older) with a new diagnosis or recurrent episode of major depressive disorder and/or generalized anxiety disorder.

Types of Interventions

We compared the following interventions:

In-person (face-to-face) psychotherapy (CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy) versus usual care, pharmacotherapy only, or combined pharmacological and psychological therapy

Individual in-person (face-to-face) psychotherapy (CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy) versus group psychotherapy (CBT, interpersonal therapy, or supportive therapy)

Types of Outcomes Measures

We examined the following outcomes:

Incremental costs

Incremental effectiveness outcomes (e.g., incremental quality-adjusted life-years, disability-adjusted life-years)

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios

Incremental net benefit

Data Extraction

We extracted the following data from the included literature:

Source (i.e., name, location, year)

Population and comparator

Interventions

Outcomes (i.e., health outcomes, costs, cost-effectiveness)

Study Applicability and Methodological Quality

We determined the usefulness of each identified study for decision-making by applying a modified applicability checklist for economic evaluations that was originally developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom. The original checklist is used to inform development of clinical guidelines by NICE. We retained questions from the NICE checklist related to study applicability and modified the wording of the questions to remove references to guidelines and to make it Ontario specific. The results of the applicability checklist and our assessment of the methodological quality of the studies included in the economic literature review are presented in Appendices 4 and 5, respectively.

Results

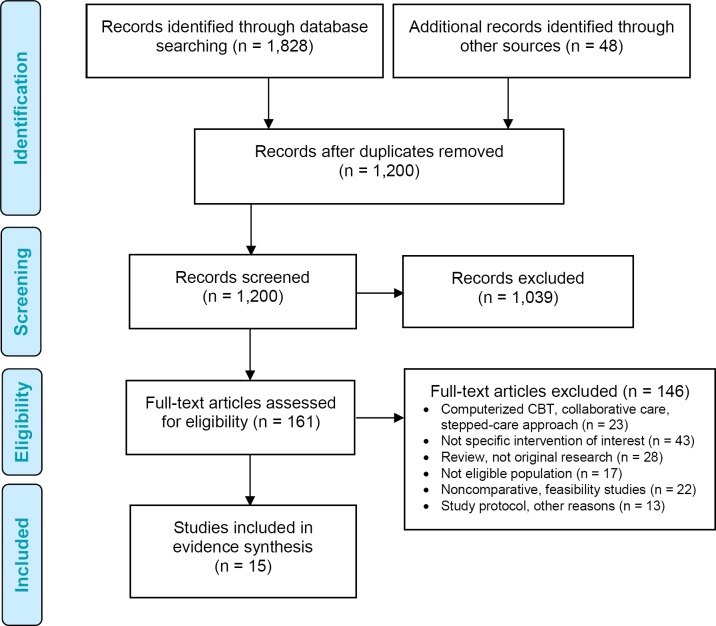

Literature Search

The database and grey literature searches yielded 1,200 citations published between January 1, 2000, and October 28, 2016 (with duplicates removed). We excluded a total of 1,039 articles based on information in the title and abstract. We then obtained the full texts of 161 potentially relevant articles for further assessment. A total of 15 studies met the inclusion criteria and were synthesized to establish the applicability of their findings to the Ontario context. Figure 2 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) for the economic evidence review.

Figure 2: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Economic Evidence Review.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.19

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.

Review of Included Economic Studies

Of the 15 eligible studies,55–69 14 examined the cost-effectiveness of CBT, 1 examined the cost-effectiveness of interpersonal therapy,58 and none examined the cost-effectiveness of supportive therapy. Nine studies were individual-level cost-effectiveness analyses conducted alongside randomized controlled trials; their sample sizes ranged from 93 to 469 participants.57–60,62,64,66–68 Six economic evaluations were model-based cost-effectiveness analyses.55,56,61,63,65,69 Only 1 model-based cost-effectiveness analysis examined the cost-effectiveness of CBT in patients with generalized anxiety disorder alone55; the rest included populations with major depressive disorder alone or both major depressive disorder and symptoms of anxiety. No studies stated whether patients were diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, but some patients were reported to have anxiety. This was not recorded in a systematic way across the studies.

Overall, CBT, provided as individual or group therapy, provided as the only therapy or in combination with pharmacotherapy, represents good value for money at different country-specific willingness-to-pay thresholds. The cost-effectiveness of interpersonal therapy, based on 1 study from the Netherlands,58 is uncertain.

In line with our two research questions, we next summarize, compare, and contrast study designs with respect to the type, perspective, and time horizon of analysis; study populations; comparative strategies; and study outcomes (i.e., effects or benefits and costs). We also describe the main cost-effectiveness findings. Tables 2a, 2b, and 2c summarize the characteristics and results of the included studies.

Table 2a:

Results of Economic Literature Review—Summary: Cost-Effectiveness of CBT for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder and/or Generalized Anxiety Disorder

| Name, Year, Location | Economic Analysis, Study Design, and Perspective | Population and Comparator | Interventions | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Costs | Cost-Effectiveness | ||||

| Wiles et al, 2016, United Kingdom68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Koeser et al, 2015, United Kingdom69 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hollinghurst et al, 2014, United Kingdom67; Wiles, 2014, United Kingdom (HTA report, duplicate publication)70 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kafali et al, 2014, Puerto Rico/United States66 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Prukkanone et al, 2012, Thailand65 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Holman et al, 2011, United Kingdom64 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sava et al, 2009, Romania62 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sado et al, 2009, Japan63 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Simon et al, 2006, United Kingdom61 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Revicki et al, 2005, United States60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Scott et al, 2003, United Kingdom59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory, second edition; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; CER, cost-effectiveness ratio; CoBalT, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in Primary Care; CrI, credible interval; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; ED, emergency department; GP, general practitioner; HDRS-17, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 17 items; HR, hazard ratio; HTA, health technology assessment; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; MDD, major depressive disorder; MDE, major depressive episode; NA, not applicable; NHS, National Health Service; NR, not reported; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PPS, Personal Public Service; REBT, rational emotive behaviour therapy; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; WTP, willingness-to-pay threshold.

This is the range reported; however, we believe there may have been a typographical error and that the correct range may be 160–300.

Table 2b:

Results of Economic Literature Review—Summary: Cost-Effectiveness of Interpersonal Therapy for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

| Name, Year, Location | Study Design and Perspective | Population and Comparator | Interventions | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Costs | Cost-Effectiveness | ||||

| Bosmans et al, 2007, Netherlands58 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; GP, general practitioner; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; IPT, interpersonal therapy; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; NR, not reported; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2c:

Results of Economic Literature Review—Summary: Cost-Effectiveness of Outpatient Models of Care for Providing In-Person CBT for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder and/or Generalized Anxiety Disorder

| Name, Year, Location | Study Design and Perspective | Population and Comparator | Interventions | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Costs | Cost-Effectiveness | ||||

| Brown et al, 2011, United Kingdom57 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vos et al, 2005, Australia56 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Heuzenroeder et al, 2004, Australia55 |

|

|

|

Total DALYs compared with current practice:

|

|

|

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; DALY, disability-adjusted life-year; GAD, general anxiety disorder; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; MDD, major depressive disorder; MDE, major depressive episode; NA, not applicable; NHS, National Health Service; NR, not reported; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; SD, standard deviation; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

The Cost-Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder and/or Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Study Design

Seven trial-based cost-effectiveness analyses (4 from the United Kingdom, 2 from the United States, and 1 from Romania)59,60,62,64,66–68 and 4 model-based cost-effectiveness analyses (2 from the United Kingdom, 1 from Thailand, and 1 from Japan)61,63,65,69 examined the cost-effectiveness of CBT (see Table 2a).

Perspective

Study perspective depended on the features of each country's health care system; thus, the U.S. studies were conducted from a health care payer's perspective, whereas the majority of the other studies were conducted from a societal perspective or included a societal perspective in a sensitivity analysis.

Time Horizon

The duration of follow-up (in trial-based cost-effectiveness analyses) or time horizon (in model-based cost-effectiveness analyses) was short in most studies, ranging from 4 to 24 months, thus not allowing enough time to account for the recurrent and chronic nature of the disorders.

Population

Studies included mixed populations consisting of people with newly diagnosed major depressive disorder and those experiencing recurrent episodes. Therefore, in the majority of the cost-effectiveness analyses we reviewed, the disorder was considered moderate or severe.

Comparators

Most studies compared CBT combined with pharmacotherapy to pharmacotherapy only (i.e., usual care). CBT was provided in the first 4 months of treatment (i.e., in the acute and continuation phases). The total number of in-person CBT sessions in the trial-based cost-effectiveness analyses ranged from 566 to 18,67 and sessions typically lasted 50 to 90 minutes. In the model-based studies, CBT was provided in 10 to 16 weekly sessions, each lasting between 50 and 60 minutes.

Outcomes: Effects and Costs

In all model-based61,63,65,69 and 3 trial-based economic analyses,64,67,68 the effectiveness of CBT versus usual care was expressed in adjusted life-year outcomes (i.e., quality-adjusted life-years [QALYs] or disability-adjusted life-years [DALYs]). The other trial-based cost-effectiveness analyses examined the benefit of CBT in terms of clinically relevant health outcomes such as mean changes in depression scale scores from baseline (i.e., symptom improvement),64,66 the number of relapses or recurrent episodes at the end of follow-up,59 and the number of depression-free days.60,62