ABSTRACT

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infects peripheral blood monocytes and triggers biological changes that promote viral dissemination and persistence. We have shown that HCMV induces a proinflammatory state in infected monocytes, resulting in enhanced monocyte motility and transendothelial migration, prolonged monocyte survival, and differentiation toward a long-lived M1-like macrophage phenotype. Our data indicate that HCMV triggers these changes, in the absence of de novo viral gene expression and replication, through engagement and activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and integrins on the surface of monocytes. We previously identified that HCMV induces the upregulation of multiple proinflammatory gene ontologies, with the interferon-associated gene ontology exhibiting the highest percentage of upregulated genes. However, the function of the HCMV-induced interferon (IFN)-stimulated genes (ISGs) in infected monocytes remained unclear. We now show that HCMV induces the enhanced expression and activation of a key ISG transcriptional regulator, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT1), via an IFN-independent but EGFR- and integrin-dependent signaling pathway. Furthermore, we identified a biphasic activation of STAT1 that likely promotes two distinct phases of STAT1-mediated transcriptional activity. Moreover, our data show that STAT1 is required for efficient early HCMV-induced enhanced monocyte motility and later for HCMV-induced monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and for the regulation of macrophage polarization, suggesting that STAT1 may serve as a molecular convergence point linking the biological changes that occur at early and later times postinfection. Taken together, our results suggest that HCMV reroutes the biphasic activation of a traditionally antiviral gene product through an EGFR- and integrin-dependent pathway in order to help promote the proviral activation and polarization of infected monocytes.

IMPORTANCE HCMV promotes multiple functional changes in infected monocytes that are required for viral spread and persistence, including their enhanced motility and differentiation/polarization toward a proinflammatory M1 macrophage. We now show that HCMV utilizes the traditionally IFN-associated gene product, STAT1, to promote these changes. Our data suggest that HCMV utilizes EGFR- and integrin-dependent (but IFN-independent) signaling pathways to induce STAT1 activation, which may allow the virus to specifically dictate the biological activity of STAT1 during infection. Our data indicate that HCMV utilizes two phases of STAT1 activation, which we argue molecularly links the biological changes that occur following initial binding to those that continue to occur days to weeks following infection. Furthermore, our findings may highlight a unique mechanism for how HCMV avoids the antiviral response during infection by hijacking the function of a critical component of the IFN response pathway.

KEYWORDS: HCMV, STAT1, macrophages, monocytes, receptor-ligand

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), which is known to infect from 60 to 100% of the human population depending on geographic location, establishes a lifelong infection of the host, with periods of latency and reactivation (1, 2). The biological outcome and severity of disease during HCMV infection are intimately linked to the immune status of the host. HCMV infection of healthy individuals is typically undiagnosed, due to relatively mild and ambiguous disease symptoms; however, HCMV has been linked to the development of multiple chronic inflammatory diseases (3), including various cardiovascular diseases (4–6) and some cancers (7), in otherwise healthy individuals. Furthermore, in immunocompromised patients, the virus is associated with severe morbidity and mortality (3, 8). For example, HCMV can cause a range of severe complications, including multiorgan failure, in transplant recipients, AIDS patients, and congenitally infected neonates (9).

The ability of HCMV to cause such a broad range of disease pathologies during infection results from the broad cellular tropism and the widespread dissemination of the virus during infection (3, 8). Multiple studies document that this viral spread is mediated predominately by infected peripheral blood monocytes. Specifically, HCMV is known to establish a cell-associated viremia (8, 10), occurring most commonly in circulating monocytes (10–13), and monocytes are known to be the primary infiltrating cell type within HCMV-infected tissues (11, 14). Peripheral blood monocytes are ideal candidates to serve as viral carriers for delivery of the virus to peripheral organ tissues because of their sentinel role in host immune surveillance, which allows them easy access to various organ systems (15, 16). In order to utilize infected monocytes to promote viral spread, however, HCMV must overcome some monocyte biological hurdles (17). For example, the virus must manipulate the normal short 1- to 3-day life span of monocytes following infection (18, 19). Furthermore, the virus must also deal with intrinsic cellular defenses designed to protect the infected cell from bacterial and viral infections (12, 15, 16). Lastly, the initial infection of monocytes by HCMV is nonproductive (20), requiring the virus to initiate the required biological changes in monocytes in the absence of newly synthesized viral gene products, which we have shown in our system are not produced until weeks following infection (12, 21; reviewed in reference 17).

We have shown that HCMV manipulates the biology of infected monocytes to overcome these obstacles, promoting multiple functional changes in the cells, which are critical for the effective spread of HCMV throughout the host and for the establishment of viral persistence (12, 21–27). For example, HCMV induces a “hyper” motility in infected monocytes, which would enhance the crawling of these monocytes along the vessel wall (12, 21, 22, 25, 26), an enhanced transendothelial migration, which would facilitate the exit of infected monocytes out of the bloodstream and into peripheral organ tissues (12, 26, 28, 29), a prolonged monocyte survival, which would provide the virus with a long-lived cellular host (12, 21, 30, 31), and a virally induced monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, which would provide a productive site for viral replication within these differentiated tissue macrophages (12, 24, 31–34). Taken together, these studies indicate that HCMV manipulates infected monocytes in order to utilize the select biological properties of the cells that are needed to enhance the spread of the virus and establish a lifelong infection.

In support, our recent global transcriptome analyses indicate in a molecular and mechanistic fashion that HCMV infection of monocytes induces an activated, proinflammatory monocyte phenotype through the upregulation of the gene ontologies associated with motility, migration, survival, and differentiation (32–35). These microarray analyses revealed that HCMV biases the polarization of infected monocytes toward an M1 proinflammatory macrophage also showing some M2 anti-inflammatory characteristics (31, 32, 34) and that the gene expression changes that occur in HCMV-infected monocytes result in a macrophage polarization phenotype that is distinct from that of macrophages polarized by lipopolysaccharide (LPS; to promote M1 polarization) or macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; to promote M2 polarization) (31).

These analyses also revealed that of the gene ontology groupings that we examined, the genes associated with the antiviral interferon (IFN) response pathway exhibited the highest proportion of genes that were upregulated by HCMV infection (34). Multiple studies have identified the upregulation of IFN-associated genes during HCMV infection of fibroblasts (36–39); however, upregulation of these genes appears to occur in an IFN-independent manner (36), suggesting that HCMV-induced interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) may be regulated in a nontraditional manner. Furthermore, IFN-like responses directed toward HCMV exhibit unique signaling requirements in various cell types. For example, ISG expression in infected human foreskin fibroblasts is dependent on interferon regulatory factor 3, but not activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) or STAT2 (40). In contrast, HCMV immediate early 1 gene (IE1)-induced ISG expression in human embryonic lung fibroblasts occurred in an activated STAT1-dependent but IFN-independent manner (41). Together, these data indicate a potential unique regulation of ISGs in HCMV-infected cells that may vary among infected cell types.

Traditionally, IFN response pathways are triggered in a virally infected cell following recognition of viral RNA or DNA by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (42). Activation of TLRs or other PRRs leads to the initiation of appropriate IFN signaling pathways, resulting in the production of IFNs, activation of downstream IFN signaling cascades, and the production of ISGs (43). Although there are reports that HCMV induces a classical interferon response following detection by cytoplasmic PRRs such as NOD2 (44) or cGAS/STING (45, 46), the induction of ISGs in HCMV-infected cells may also occur through an alternative mechanism, as the production of HCMV-induced ISGs can be stimulated by viral glycoproteins alone (37, 47–49). Further evidence for a distinct mechanism comes from studies showing that this induction occurs in a TLR-independent manner (50); however, the precise mechanism for how the upregulation of ISGs occurs during HCMV infection remains unclear.

Our laboratory has shown that HCMV utilizes the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and β1 and β3 integrins on the surface of monocytes as critical coreceptors for the viral entry process (21, 22, 51). Further, a number of our studies indicate that HCMV capitalizes on the signaling capacity of these surface receptors to alter monocyte biology in specific ways that promote a successful infection. For example, we have recently shown that HCMV-induced signaling resulting from viral binding to these receptors drives a unique nuclear translocation pattern for the virus following infection of monocytes compared to cells that are initially permissive for viral replication, such as fibroblasts and endothelial cells (52). Moreover, we have shown that HCMV-induced signaling through EGFR and β1 and β3 integrins is required for the HCMV-induced biological changes in infected monocytes described above, including their polarization toward an M1 proinflammatory cell type, and the upregulation of motility, survival, and differentiation (30, 32–34). Because these receptor/ligand interactions are critical for HCMV-induced changes in infected monocytes, we hypothesized that EGFR and/or integrin signaling plays a role in the upregulation of the HCMV-induced ISGs that we observed in our transcriptome analyses and that these ISGs play a role in the establishment of the long-lived proinflammatory monocyte/macrophage that supports productive infection (33, 34).

Based on our previous studies indicating that EGFR and integrin signaling are critical for changes that promote the progression of the viral life cycle, the upregulation of antiviral protein-associated ISGs through this pathway initially seemed counterintuitive. Studies of the specific effects of IFN-like responses on the HCMV viral life cycle have produced conflicting results. For example, it has been reported that IFN treatment does little to inhibit the viral life cycle (53, 54), while other reports indicate that IFNs are effective at the inhibition of HCMV replication (55, 56). To add greater complexity to the potentially diverse role for IFN responses in HCMV infection, IFN-γ, when combined with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), was shown to produce an HCMV replication-permissive macrophage that was resistant to future IFN-γ-induced cytokines (57). Further, both of the interferon-inducible (IFI) proteins IFI16 (58) and viperin (59, 60) have been shown to enhance HCMV gene expression and replication in fibroblasts. Thus, a potential proviral effect for IFN-like responses during HCMV infection is plausible, especially because it has been established that IFN-associated genes can play diverse roles in normal cellular homeostatic processes (such as in cellular survival, proliferation, and differentiation [61–63]), aside from their role in antiviral immunity.

To test our hypothesis, we investigated the requirement for EGFR and integrin signaling in the upregulation of HCMV-induced ISGs and the potential functional roles of select ISGs in infected monocytes. Our transcriptome analyses indicated that the majority of the HCMV-induced ISGs were regulated by EGFR and/or integrin signaling in infected monocytes and that the specific profile of ISGs that were upregulated differed from that seen in traditional IFN responses. Focusing in on potential regulators of these virus-induced ISGs, we identified that STAT1, a key transcription factor involved in the regulation of ISG production (43), was rapidly activated in infected monocytes and that this activation occurred via a nontraditional, IFN-independent activation cascade involving EGFR and integrins. Moreover, we discovered that HCMV-induced STAT1 helps direct motility, differentiation, and polarization of infected monocytes. We suggest that we have identified a proviral outcome for the activation of the traditionally antiviral player, STAT1, during HCMV infection of monocytes. Moreover, our data suggest that STAT1 may serve as one molecular convergence point linking the functional changes triggered by viral binding-induced signaling and the signaling that occurs following viral entry.

RESULTS

STAT1 is upregulated following HCMV infection of monocytes.

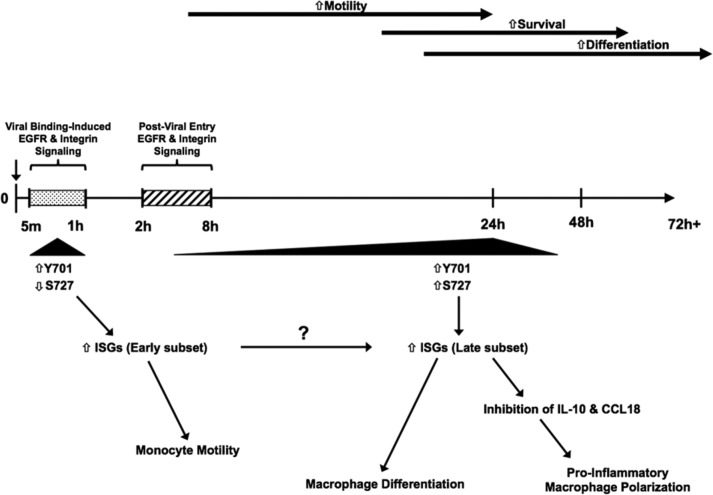

Our previous microarray analyses indicated that ISGs were upregulated during HCMV infection of monocytes at 24 hours postinfection (hpi) (GSE17948 [22] and GSE24238 [51]). We utilized Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software to identify transcription factors that could potentially serve as upstream regulators driving these gene expression changes. STAT1 and a number of interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) (Fig. 1A) were significantly upregulated in HCMV- versus mock-infected monocytes. We narrowed our focus to examine the mechanisms for the regulation of STAT1 during HCMV infection of monocytes because STAT1, which is well characterized as a key regulator of IFN-like responses and downstream ISG expression (64), is the most significantly upregulated of the transcription factors identified from our microarray analyses (Fig. 1A). To confirm the results of our microarray analysis, we performed reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and Western blot analyses to determine if STAT1 is upregulated following HCMV infection of monocytes. We observed an increase in steady-state STAT1 mRNA levels in HCMV-infected monocytes at 24 hpi compared to uninfected monocytes (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, Western blot analysis revealed that STAT1 protein was increased in monocytes at 24 hpi compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 1C). These data confirm that STAT1 mRNA and protein are upregulated during HCMV infection of monocytes.

FIG 1.

STAT1 is upregulated following HCMV infection of monocytes. (A) Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software was used to analyze our previous microarray data (22, 51) to determine the top upstream regulators of the distinct transcriptome seen in HCMV-infected monocytes. The top transcription factors identified by IPA are shown with the fold change in gene expression relative to uninfected monocytes, the direction of gene expression changes, and the calculated P value of overlap, a statistical analysis value based on Fisher's exact test [P < 0.01] that determines the likelihood of a given transcriptional upstream regulator by measuring the overlap between (i) gene expression changes in a particular data set and (ii) gene expression changes that are known to be regulated by that specific transcriptional regulator. (B and C) Monocytes were mock or HCMV infected for 24 h. RNA was harvested for RT-PCR utilizing primers specific for STAT1 or 18S RNA (B). Protein lysates were harvested for Western blot analysis utilizing antibodies specific for STAT1 or actin (C). Panels are representative of at least three individual experiments from separate healthy human donors.

STAT1 is activated during HCMV infection of monocytes.

Although STAT1 expression is increased in HCMV-infected monocytes, in order to have full biological activity, STAT1 must first be phosphorylated at its primary phosphorylation site, tyrosine residue 701 (Y701) (65–67). This phosphorylation event leads to the structural rearrangement of STAT1 homodimers, creating a conformational nuclear localization signal and promoting specific DNA binding (68–70). The binding of activated STAT1 dimers to their target DNA induces the transcriptional activity of STAT1 and its control of the expression of STAT1-dependent ISGs (71). Although phosphorylated STAT1 translocates to the nucleus within minutes of IFN stimulation, nuclear accumulation of activated STAT1 is a transient event, as STAT1 is actively exported from the nucleus and “recycled” following subsequent activation events (72). Newer data suggest that STAT1 activity can also be induced by phosphorylation at a secondary phosphorylation site, serine residue 727 (S727), which can enhance Y701 phosphorylation-mediated activity (67, 73–77) and regulate the transcription of Y701-independent ISGs (67, 73–76).

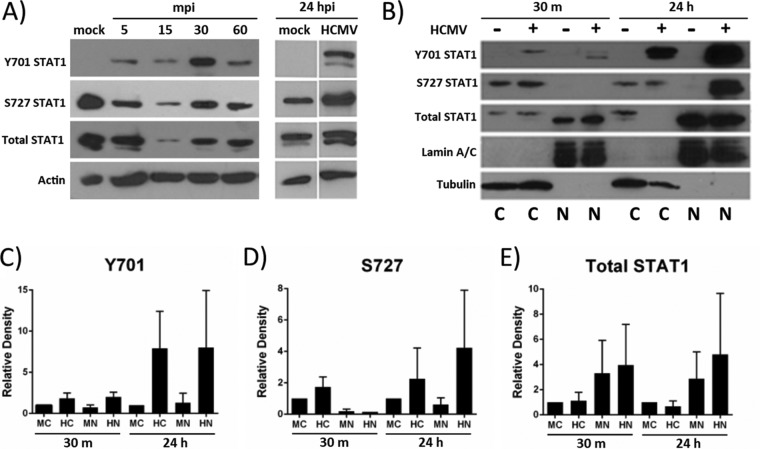

Western blot analysis of the phosphorylation status of STAT1 in monocytes over a time course of HCMV infection indicated that uninfected monocytes had low to undetectable levels of Y701 phosphorylated STAT1 (Fig. 2A). However, HCMV infection of monocytes rapidly phosphorylated STAT1 at Y701—within 5 min postinfection (mpi) (Fig. 2A)—a time at which newly synthesized IFNs are not yet made. Furthermore, the phosphorylation of STAT1 occurred in a biphasic manner, with early (30 mpi) and late (24 hpi) peaks of phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). STAT1 from uninfected monocytes was constitutively phosphorylated at S727 at both the early (30 mpi) and late (24 hpi) time points, and HCMV infection increased the phosphorylation of S727 at 24 hpi (but not at 30 mpi) (Fig. 2A). We noted a sharp decrease in total STAT1 (and a resulting decrease in Y701 and S727 phosphorylation) at 15 mpi; however, the profile of STAT1 phosphorylation followed a trend comparable to that of the other early time points (increased Y701 and decreased S727 phosphorylation compared to mock-infected cells) (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

STAT1 is activated by HCMV infection of monocytes. (A) Monocytes were mock infected or HCMV infected for the indicated times. Protein lysates were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting utilizing antibodies specific for STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 or S727, total STAT1, or actin. (B) Nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) extracts were collected and analyzed by Western blotting utilizing antibodies specific for STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 or S727, total STAT1, lamin A/C (a loading control for nuclear extracts), and tubulin (a loading control for cytoplasmic extracts). Panels are representative of at least three individual experiments from separate healthy human donors. (C to E) Densitometry analysis of Western blots was performed using ImageJ software to quantify the relative amounts of total STAT1 (E) or STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 (C) or S727 (D) for each sample relative to the amounts in the cytoplasmic mock-infected samples at each time point. Results are plotted as means ± SEM from 3 separate experiments. M, mock infected; H, HCMV infected; C, cytoplasmic fraction; N, nuclear fraction.

To determine whether STAT1 translocated to the nucleus at early or late phases of activation, we performed Western blot analyses of nuclear and cytoplasmic cellular extracts at 30 mpi and 24 hpi to detect pan-STAT1 or phosphorylated STAT1 (Y701 and S727) (Fig. 2B). Densitometry was performed on the Western blots from three separate experiments to quantitate the mean relative expression levels of total STAT1 (Fig. 2E) and STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 (Fig. 2C) or S727 (Fig. 2D). Our analyses revealed that STAT1 is present in the nucleus and cytoplasm of uninfected and HCMV-infected monocytes at both early and late time points (Fig. 2B). Consistent with data shown in Fig. 2A, mock-infected monocytes had nearly undetectable amounts of Y701-phosphorylated STAT1 at 30 mpi and 24 hpi (Fig. 2B). HCMV-infected monocytes, on the other hand, had an ∼2-fold increase (over mock-infected monocytes) in Y701-phosphorylated STAT1 at 30 mpi, and an ∼8-fold increase at 24 hpi in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions (Fig. 2B and C), indicating that STAT1 may be fully activated and able to regulate the transcriptional activity of ISGs in infected monocytes at early and late times postinfection. Furthermore, we identified the presence of S727-phosphorylated STAT1 in the cytoplasm of uninfected and HCMV-infected monocytes at both 30 mpi and 24 hpi, but the presence of nuclear S727-phosphorylated STAT1 was detected primarily in HCMV-infected monocytes at 24 hpi (Fig. 2B and D). Overall, these studies indicated that HCMV induces an early phase and a late phase of STAT1 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation in infected monocytes, where STAT1 is activated early via phosphorylation at Y701 and late via phosphorylation at both Y701 and S727. Given that S727- and Y701-phosphorylated STAT1 are known to differ to some degree in their targeting of ISGs (67, 73–76, 78), these data also suggest that HCMV-induced STAT1 may regulate the transcription of different subsets of STAT1-dependent ISGs at each time point.

STAT1 activation occurs in a nontraditional IFN-independent manner in HCMV-infected monocytes.

During typical antiviral responses, STAT1 is phosphorylated following the binding of IFN to IFN receptors (IFNRs) (71). However, the early phosphorylation (30 mpi) of STAT1 in HCMV-infected monocytes (Fig. 2A) occurs before de novo synthesis of IFNs can occur and involves the nuclear translocation of only Y701-phosphorylated STAT1, and not S727-phosphorylated STAT1 (Fig. 2B), suggesting that a potential IFN-independent activation cascade may be responsible for the early STAT1 activation seen in infected monocytes. Despite this seemingly atypical early activation of STAT1, HCMV-induced de novo cellular protein synthesis does occur prior to the late phase (24 hpi) of STAT1 activation in infected monocytes (Fig. 2A); thus, a traditional IFN-dependent pathway could still be responsible for the late activation of STAT1 during infection. We wanted to determine if STAT1 was activated in an IFN-independent manner in HCMV-infected monocytes and if the early and late stages of STAT1 activation were regulated differently.

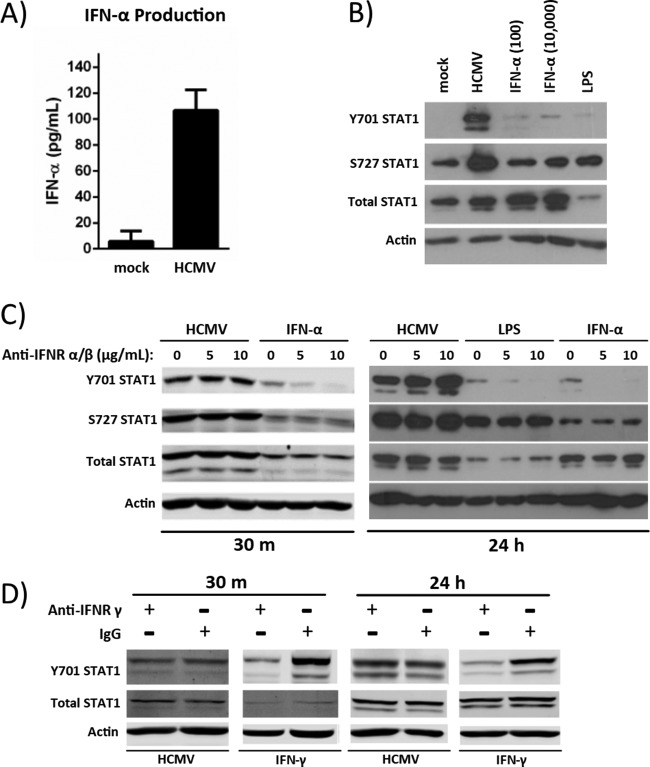

Our microarray data showed only a limited type I IFN gene expression, with IFN-α being the predominant IFN upregulated in HCMV-infected monocytes (GEO accession numbers GSE17948 [22] and GSE24238 [51]). These same data suggested a downregulation of IFN-γ receptor gene expression. In support, production of the type II IFN, IFN-γ, is associated predominantly with T cells and not with monocytes/macrophages (79). We therefore initially focused our studies on the potential role of IFN-α signaling in the HCMV-induced activation of STAT1 in monocytes. We first analyzed the production of IFN-α by HCMV-infected monocytes at 24 hpi by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We determined that a low level of IFN-α (∼107 pg/ml) was secreted by monocytes (2 million cells) following HCMV infection (Fig. 3A), which is dramatically less than that reported from monocytes treated with Poly(I·C) (3,980.7 pg/ml for 1 million cells [80]). We next compared STAT1 phosphorylation in HCMV-infected monocytes versus monocytes treated with low (100 pg/ml) or high (10,000 pg/ml) concentrations of IFN-α at 24 h (Fig. 3B). These studies indicated that neither the low dose of IFN-α, which was similar to the amount of IFN-α produced by HCMV-infected monocytes at 24 hpi, nor the high dose of IFN-α, which was approximately 100 times the amount of IFN-α produced by HCMV-infected monocytes at 24 hpi, induced the phosphorylation of STAT1 at Y701 or S727 like that seen in HCMV-infected monocytes (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, stimulation with LPS (10 μg/ml), which is known to induce the production of type I IFN in monocytes, did not induce the level of STAT1 phosphorylation or total STAT1 upregulation in monocytes that is seen following HCMV infection (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these data suggest that the phosphorylation of STAT1 at 24 hpi is likely regulated by a mechanism not dependent on IFN-α stimulation.

FIG 3.

STAT1 activation in infected monocytes occurs in an IFN-independent manner. (A) Two million monocytes were mock infected or HCMV infected for 24 h. Cellular supernatants were collected for quantification of IFN-α by ELISA. Results are plotted as the average concentration ± standard deviation for triplicate samples from 2 healthy donors. (B) Monocytes were mock infected or HCMV infected or treated with IFN-α (100 pg/ml or 10,000 pg/ml) or LPS (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Protein lysates were harvested, and Western blot analysis was performed to examine expression levels of Y701-phosphorylated, S727-phosphorylated, and total STAT1. Actin was used as a loading control. (C and D) Monocytes were pretreated with 0, 5, or 10 μg/ml of neutralizing antibody to IFNR α/β (C) or 10 μg/ml of neutralizing antibody to IFNR γ (D) for 1 h. Samples labeled as treated with 0 μg/ml of neutralizing antibody were instead treated with 10 μg/ml of matched isotype (IgG) control antibody. Pretreated monocytes were then infected with HCMV or treated with either 100 ng/ml of LPS, 10,000 pg/ml of IFN-α (C), or 10,000 pg/ml of IFN-γ (D) for 30 mpi or 24 hpi. Protein lysates were harvested at the indicated times, and Western blot analysis was performed utilizing antibodies specific for STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 or S727, total STAT1, and actin. Panels are representative of at least three individual experiments from separate healthy human donors.

To further examine if type I IFN signaling is required for the induction of STAT1 phosphorylation in infected monocytes, we utilized an IFN receptor α/β (IFNR α/β)-neutralizing antibody. These studies indicated that STAT1 phosphorylation in HCMV-infected monocytes occurs independently of type I IFN receptor signaling, as we saw no observable decrease in STAT1 Y701 or S727 phosphorylation in the presence of the IFNR α/β neutralizing antibody at either 30 mpi or 24 hpi (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, we found that the phosphorylation of STAT1 by HCMV occurs via a mechanism distinct from that seen with LPS or IFN-α treatment, because IFN-α-induced STAT1 phosphorylation (30 mpi) and both LPS- and IFN-α-induced STAT1 phosphorylation (24 hpi) at the primary Y701 phosphorylation site were reduced in the presence of neutralizing antibody to IFNR α/β (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these data indicate that although HCMV infection of monocytes induces the production of low levels of IFN-α during infection, the phosphorylation of STAT1 occurs in a type I IFN-independent manner distinct from STAT1 activation following LPS or IFN-α treatment of monocytes.

Although our microarray data showed no altered expression of IFN-γ in HCMV-infected monocytes and indicated a downregulation of the IFN-γ receptor (IFNR γ) in HCMV-infected versus mock-infected monocytes, we wanted to rule out the possibility that type II IFN signaling may play a role in the regulation of STAT1 in HCMV-infected monocytes. For this experiment, we used an IFNR γ-neutralizing antibody in combination with HCMV infection or IFN-γ treatment (Fig. 3D). We show only total STAT1 and STAT1 phosphorylated at the primary Y701 phosphorylation site (and not pS727 STAT1), as no apparent changes were seen in S727 phosphorylation after treatment with the IFNR γ-blocking antibodies in any of the experimental treatment groups, similar to the results seen with IFN-α treatment (Fig. 3C). We saw no observable decrease in HCMV-induced STAT1 expression or in STAT1 Y701 phosphorylation in the presence of IFNR γ-neutralizing antibodies compared to IgG control antibodies at either 30 mpi or 24 hpi, indicating that IFN-γ does not likely play a role in the expression and activation of STAT1 in HCMV-infected monocytes (Fig. 3D).

EGFR and/or integrin signaling is required for HCMV-induced ISG expression and for STAT1 activation.

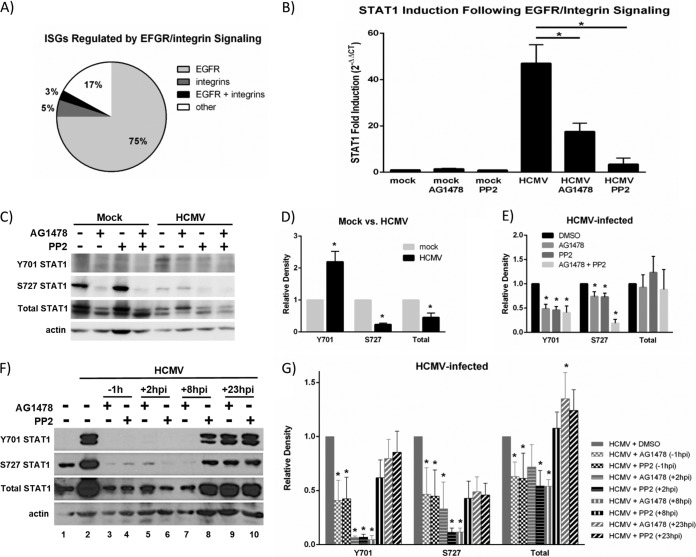

Our studies indicate that activation of STAT1 (and likely expression of downstream STAT1-dependent ISGs) occurs in an IFN-independent manner (Fig. 3); however, the mechanism by which these ISGs are stimulated in HCMV-infected monocytes has yet to be identified. Previous studies in fibroblasts have indicated that HCMV-induced ISG expression is due to the binding of HCMV glycoprotein B (gB) to an unidentified cellular receptor (37, 47, 49). HCMV gB has been shown to bind to multiple cellular receptors on various cell types, including EGFR (81, 82), integrins (82, 83), and TLR2 (84, 85). Because receptor-ligand interactions were shown to be required for HCMV-induced ISG expression in fibroblasts and because we showed that the binding and activation of EGFR and integrins by HCMV were required for viral entry and the induced gene expression and biological changes in infected monocytes (21, 22, 51), we investigated a potential role for EGFR and integrin signaling in the upregulation of ISGs during HCMV infection of monocytes. Using Genesifter software, we reanalyzed our previous transcriptome data identifying the HCMV-induced genes that were regulated by EGFR and/or integrins at 24 hpi (GSE24238 [51], GSE17948 [22]) to determine whether the HCMV-induced ISGs in monocytes were regulated by EGFR and/or integrins. We found that the upregulation of a majority of HCMV-induced ISGs was dependent on EGFR (75%), with a small contribution from integrin signaling alone (3%) or signaling through both receptors (5%) (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, we identified that the upregulation of some ISGs (17%) occurred in an EGFR- and integrin-independent manner, suggesting the existence of multiple ISG regulatory pathways in HCMV-infected monocytes (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

STAT1 expression and activation are dependent on EGFR and integrin signaling. (A) Our previous microarray data (22, 51) were analyzed to determine the role of EGFR or integrin signaling in the expression of HCMV-induced ISGs. The expression of individual ISGs that were upregulated (≥1.5-fold change increase versus mock infection) by HCMV infection was compared to their expression in the presence of EGFR (AG1478) and/or integrin (PP2) inhibitors during infection. ISGs whose expression was downregulated (≥1.5-fold decrease versus HCMV infection) in the presence of one or both inhibitors were considered to be regulated by EGFR and/or integrin signaling. The percentage of genes regulated by EGFR and/or integrins is represented. (B) Monocytes were pretreated with AG1478 or PP2 and then mock or HCMV infected. RNA was harvested for RT-qPCR utilizing primers specific for STAT1 or 18S. Results are plotted as means ± SEM of fold induction over mock treatment (2−ΔΔCT) from 3 separate experiments. Student's t tests were performed, and a P value of <0.05 (indicated by asterisks) was used as a measure of statistical significance between samples. (C) Monocytes were pretreated with AG1478 or PP2 and then mock or HCMV infected. Protein lysates were harvested at 30 mpi and used for Western blot analyses utilizing antibodies specific for STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 or S727, total STAT1, or actin. (D and E) Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software to quantify the expression levels of Y701-phosphorylated, S727-phosphorylated, or total STAT1 relative to the levels in mock-infected monocytes (D) or HCMV-infected monocytes treated with DMSO (E) after normalization to actin loading control. Results are plotted as means ± SEM from 3 separate experiments. Student's t tests were performed, and a P value of <0.05 (indicated by asterisks) was used as a measure of statistical significance between samples, compared to mock-infected (D) or HCMV-infected monocytes treated with DMSO (E). (F) Monocytes were pretreated with AG1478 or PP2 1 h prior to infection (−1 hpi) or infected and then treated with AG1478 or PP2 at +2 hpi, +8 hpi, or +23 hpi. Protein lysates were harvested at 24 hpi. Protein lysates were used for Western blot analyses utilizing antibodies specific for STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 or S727, total STAT1, or actin. (G) Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software to quantify the expression levels of Y701-phosphorylated, S727-phosphorylated, or total STAT1 relative to the levels in HCMV-infected monocytes treated with DMSO after normalization to actin loading control. Results are plotted as means ± SEM from 3 separate experiments. Student's t tests were performed, and a P value of <0.05 (indicated by asterisks) was used as a measure of statistical significance between samples, compared to HCMV-infected monocytes treated with DMSO.

Because STAT1 is known to play a critical role in the transcriptional regulation of ISGs, and because the upregulation of the majority of the ISGs identified in our transcriptome analyses was dependent on EGFR and/or integrin signaling, we postulated that the expression and activation of STAT1 during HCMV infection of monocytes may be dependent on EGFR and/or integrin signaling. STAT1 can be activated by tyrosine kinases downstream of activated growth factor receptors, including EGFR (64); however, a distinct role for integrin signaling in the activation of STAT1, to our knowledge, has not yet been established. By utilizing the pharmacological inhibitors AG1478 (an EGFR kinase inhibitor [22]) and PP2 (an Src inhibitor that inhibits HCMV-induced integrin signaling [51]), we determined that the upregulation of STAT1 mRNA at 24 hpi in infected monocytes (∼46-fold increase over mock) was dependent on both EGFR and integrin signaling; the upregulation of STAT1 mRNA was significantly diminished in the presence of these inhibitors (only ∼14-fold and ∼5-fold increase over mock, respectively) (Fig. 4B).

To begin to address a potential role for EGFR and integrin signaling in the phosphorylation of STAT1 during infection, we performed Western blot analyses of infected monocytes in the presence or absence of AG1478 and PP2 at 30 mpi (Fig. 4C) and 24 hpi (Fig. 4F, lanes 1 to 4). For each of these studies, we pretreated monocytes with either AG1478 or PP2 1 h prior to infection (−1 h in Fig. 4F) and then infected them with HCMV for 30 m (Fig. 4C) or 24 h (Fig. 4F, lanes 1 to 4) before harvesting cell lysates for Western blot analysis. Densitometry analyses were performed using ImageJ software to quantify the levels of STAT1 total protein and STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 or S727 across 3 separate experiments (Fig. 4D, E, and G). These studies indicated that in HCMV-infected monocytes, the phosphorylation of STAT1 at Y701 was increased at 30 mpi, while total STAT1 and S727-phsophorylated STAT1 were decreased at 30 mpi compared to mock-infected monocytes (Fig. 4C and D), consistent with results shown in Fig. 2A. Furthermore, at 30 mpi, the increased phosphorylation of STAT1 at Y701 and the low levels of phosphorylation of STAT1 at S727 were dependent on both EGFR and integrin signaling, because phosphorylation at these sites was significantly deceased when cells were pretreated with EGFR or integrin signaling inhibitors (Fig. 4C and E). At 24 hpi, the increased phosphorylation of STAT1 at Y701 and S727 also required both EGFR and integrin signaling, because phosphorylation at these sites was significantly diminished when monocytes were pretreated for 1 h prior to infection (−1 h, lanes 3 and 4) with EGFR or integrin signaling inhibitors (Fig. 4F and G). However, because pretreatment of monocytes with AG1478 and/or PP2 also inhibits efficient viral entry into monocytes (22, 51), we could not rule out the possibility that the EGFR- and integrin-dependent activation of STAT1 at 24 hpi observed with pretreatment of AG1478 or PP2 was entry dependent, rather than EGFR or integrin dependent. Therefore, we infected monocytes for 2 h, 8 h, or 23 h, allowing the EGFR- and integrin-dependent viral entry events (which we have shown occur by 1 hpi [22, 51, 86]) to proceed, before treating the infected monocytes with AG1478 or PP2 to inhibit EGFR or integrin signaling at the indicated times postinfection (+2 h, lanes 5 and 6; +8 h, lanes 7 and 8; +23 h, lanes 9 and 10) (Fig. 4F). These studies revealed that inhibition of EGFR or integrin signaling at 2 hpi (+2 h) and inhibition of EGFR signaling, but not integrin signaling, at 8 hpi (+8 h) abolished HCMV-induced STAT1 Y701 and S727 phosphorylation and diminished the upregulation of total STAT1 at 24 hpi (Fig. 4F and G), suggesting that the late activation and upregulation of STAT1 are dependent on both EGFR and integrin signaling that occurs after viral entry into monocytes. However, inhibition of EGFR and integrin signaling at 23 hpi (+23 h) had no effect on the phosphorylation or upregulation of STAT1 at 24 hpi (Fig. 4F and G), indicating that although EGFR and integrin signaling continues to fire hours after infection, the sustained phosphorylation of STAT1 at 24 hpi is not dependent on late EGFR and integrin signaling. Moreover, these studies suggest that EGFR and integrins not only signal at the cell surface during viral binding and entry into monocytes to induce the early phosphorylation of STAT1 at Y701 (Fig. 4C) but also continue to signal following viral entry (after 2 to 8 hpi and before 23 hpi) to induce the late activation of STAT1 at Y701 and S727 (Fig. 4F). This finding is consistent with our previous studies, where we show that HCMV-induced integrin signaling has prolonged effects on monocyte biology (30), and with unpublished microarray data, which demonstrate that HCMV-induced EGFR- and integrin-signaling alters monocyte transcription as late as 2 weeks postinfection (S. J. Cieply, D. Collins-McMillen, S. Jeng, E. V. Stevenson, S. McWeeney, U. Cvek, M. Trutschl, and A. D. Yurochko, unpublished data). The mechanisms of chronic EGFR/integrin signaling as well as the signaling link between the EGFR/Src kinases and phosphorylation of STAT1 are being explored in more detail as part of our ongoing studies in the lab.

HCMV induces distinct expression profiles of STAT1-associated ISGs at 4 hpi and 24 hpi.

Taken together, our data suggest that the biphasic activation of STAT1 (Fig. 2A and B) may represent two separate molecular processes that regulate different functional aspects in infected monocytes. First, viral binding to EGFR and integrins on the surface of monocytes triggers the early (30 mpi) phosphorylation of STAT1 at Y701, with a simultaneous decrease in STAT1 S727 phosphorylation (Fig. 4C and E). This event leads to the nuclear translocation of Y701-phosphorylated STAT1 (Fig. 2B), which would be available to bind DNA to regulate the transcription of early-expressed target genes. Following STAT1's nuclear translocation at 30 mpi (Fig. 2B) and probable subsequent transcription factor activity, Y701 phosphorylation decreases, returning to basal levels around 1 hpi (Fig. 2A), indicating that the EGFR- and integrin-dependent early activation of STAT1 at 30 mpi (that occurs during viral binding and entry) is a transient event. On the other hand, the late phosphorylation of STAT1 observed at 24 hpi is initiated between 2 to 8 hpi (Fig. 4F and G), which is downstream of the EGFR and integrin signaling that occurs during entry into monocytes (and after the early 30-mpi activation of STAT1). These data indicate that the early and late phases of activation of STAT1 during HCMV infection of monocytes are likely regulated by distinct mechanisms downstream of EGFR and integrin signaling.

Furthermore, our observation of the differential STAT1 phosphorylation profiles at 30 mpi (increased Y701 and decreased S727) and 24 hpi (increased Y701 and S727) (Fig. 2A) suggests that the early and late phases of STAT1 activation may regulate distinct biological changes. Phosphorylation of STAT1 at Y701 is known to regulate the dimerization, nuclear translocation, and DNA-binding activity of STAT1, which are required events for STAT1's transcriptional activity (67). Phosphorylation of STAT1 at S727 has been shown to enhance the transcriptional activity of STAT1 phosphorylated at Y701 and to be specifically required in combination with Y701 phosphorylation for the entirety of the cellular response to type I IFN and for antiviral immunity (78). Furthermore, phosphorylation of STAT1 at S727 has been shown to independently mediate STAT1's transcriptional activity (67, 74, 76, 77) and possibly the formation of coactivator complexes (77). Taken together, these data suggest that the early (30 mpi) and late (24 hpi) activation of STAT1 may regulate distinct transcriptional profiles in infected monocytes, which likely translates to the coordinated regulation of the different biological changes required for the infection of monocytes.

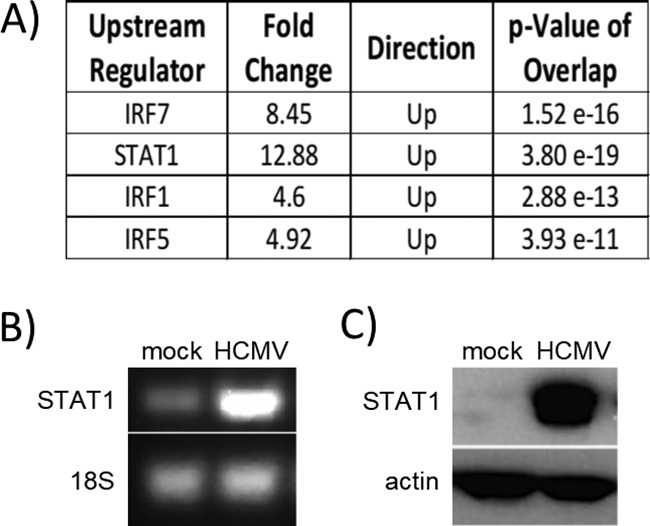

To begin to address whether the early and late phases of STAT1 activation may regulate different transcriptional profiles during infection, we utilized Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software to analyze our previous transcriptome arrays at 4 hpi (GSE11408 [34]) and 24 hpi (GSE17948 [22] and GSE24238 [51]). Briefly, we identified the genes that were upregulated or downregulated ≥1.5-fold (which we considered to be significantly upregulated or downregulated) in monocytes infected with HCMV for 4 h or 24 h (in comparison to mock-infected monocytes) using Genesifter. We then utilized IPA software to determine whether the genes identified as key molecules in the canonical STAT1 signaling pathway were regulated differently at 4 h and at 24 h. From these analyses, we generated a heat map showing the degree of upregulation (red) and downregulation (green) of STAT1 pathway-associated genes at 4 and 24 hpi (Fig. 5). We observed that the expression of ∼14.3% of genes associated with the STAT1 pathway was unchanged at 4 hpi and 24 hpi, the expression of ∼38% of genes associated with the STAT1 pathway was upregulated or downregulated to a similar degree at 4 hpi and 24 hpi, and the expression of ∼47.7% of the genes associated with the STAT1 pathway was differentially regulated at 4 hpi versus 24 hpi. Furthermore, we found that ∼6% of STAT1-associated genes were more upregulated at 4 hpi than at 24 hpi, while ∼35.7% of STAT1-associated genes were more highly upregulated at 24 hpi than at 4 hpi. Overall, these data support our hypothesis that the early and late activation of STAT1 in HCMV-infected monocytes regulates different transcriptional profiles during the course of infection.

FIG 5.

The expression pattern of ISGs associated with the STAT1 pathway at 4 hpi is different from that at 24 hpi. Our previous microarray analyses at 4 hpi (GSE11408 [34]) and 24 hpi (GSE17948 [22] and GSE24238 [51]) were analyzed by Genesifter software. The genes that were ≥1.5-fold upregulated or downregulated by infection compared to those in mock-infected monocytes at 4 hpi or 24 hpi were considered significantly up- or downregulated. (A) These genes were then analyzed with IPA software to identify the genes known to be associated with the canonical STAT1 signaling pathway. Results are represented as a heat map showing the degree of upregulation (red) or downregulation (green) of STAT1 pathway-associated genes at 4 and 24 hpi. (B) IPA software analysis was utilized to compare the gene expression changes at 4 hpi and 24 hpi to identify the genes that had altered gene expression changes at only 4 hpi but not 24 hpi (white; 973 genes), altered expression at only 24 hpi but not 4 hpi (dark gray; 1,182 genes), or altered expression at both 4 hpi and 24 hpi (light gray; 452 genes).

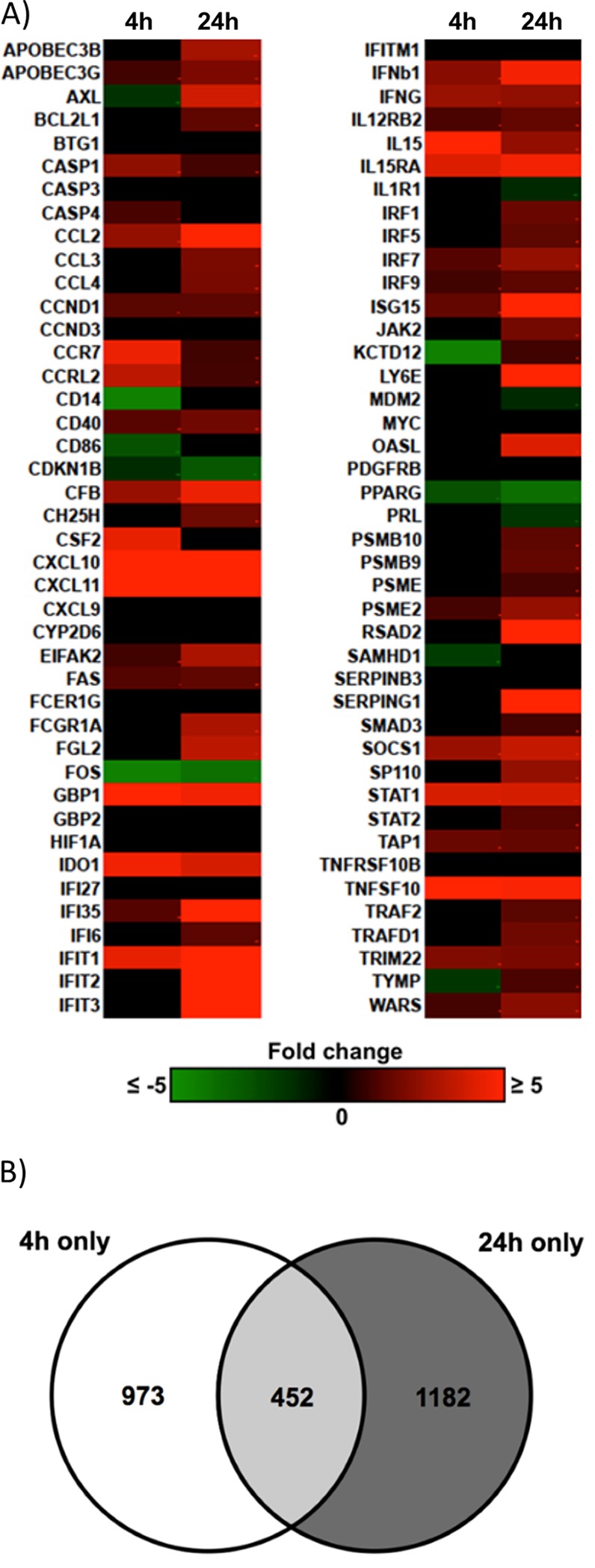

To determine the potential STAT1-regulated transcriptional profiles induced at 4 hpi and 24 hpi that may regulate different biological functions, we utilized IPA software to compare the cellular functional pathways that were upregulated or downregulated at 4 hpi, 24 hpi, or at both time points in infected monocytes. Of the genes that were significantly upregulated or downregulated (>1.5-fold change) by HCMV infection, 973 genes were significantly upregulated or downregulated at 4 hpi but not 24 hpi, 1,182 genes were significantly upregulated or downregulated at 24 hpi but not 4 hpi, and 452 genes were significantly upregulated or downregulated at both 4 hpi and 24 hpi (Fig. 5B). After comparing the overall activation scores of the genes grouped into these functional pathways, we generated a list of biological functions that were regulated by HCMV infection at either 4 hpi or 24 hpi. These analyses revealed a pattern of gene expression changes whereby the gene ontologies that were most differentially regulated (as indicated by the P value) at 4 hpi were those associated with cellular migration and motility (Table 1). Genes from these ontologies were uniformly significantly upregulated (as indicated by Z-scores above 1.97). In contrast, the pattern of gene expression changes that were more significantly regulated at 24 hpi resulted in altered regulation of cellular pathways most associated with cellular survival and apoptosis and cellular differentiation (Table 1). Although genes from these ontologies were significantly regulated in response to HCMV infection (as indicated by the P value), there was a nearly equal mix of upregulation and downregulation (as indicated by Z-scores closer to zero). Taken together, these data indicate that the gene expression changes initiated at 4 hpi versus 24 hpi appear to regulate different cellular functions, which could potentially be mediated, at least in part, by the differential activation (early and late) of STAT1.

TABLE 1.

Top functional changes associated with the HCMV-induced gene expression changes at 4 hpi and/or 24 hpia

Our previous microarray analyses at 4 hpi (GSE11408 [34]) and 24 hpi (GSE17948 [22] and GSE24238 [51]) were analyzed by Genesifter software. The genes that were ≥1.5-fold upregulated or downregulated by infection when compared to mock-infected monocytes at 4 hpi or 24 hpi were considered significantly up- or downregulated. From the significantly regulated genes, we identified the top cellular functional ontologies that were associated with the profile of HCMV-induced gene expression changes for each time point. The top functional changes for each time point are listed in order of the most significant P values for activation (a measure of how many genes associated with that ontology are significantly regulated). Functional ontology groups are also further analyzed by activation Z-score (a directional measure where a Z-score of greater than 1.97 indicates significant upregulation and a Z-score of less than −1.97 indicates significant downregulation). To aid in visualization of the larger regulatory trends, we have highlighted the specific gene ontology groups listed in the table to classify them as either cell motility (blue) or cell survival/differentiation (red).

STAT1 is required for HCMV-induced monocyte motility.

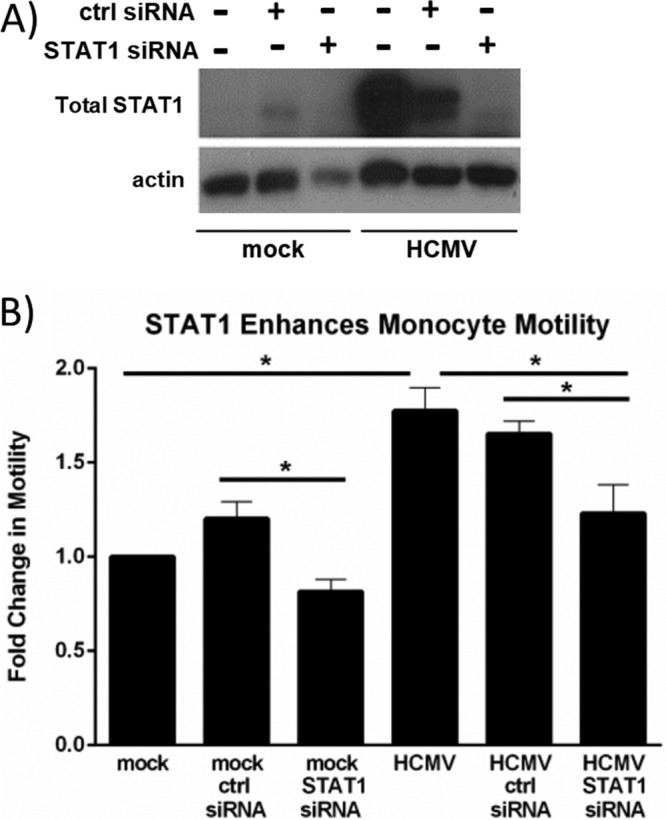

Our comparison of the functional pathways activated at 4 and 24 hpi suggested that the early transcriptional changes in HCMV-infected monocytes were predominantly associated with cellular activation and movement (Table 1). These findings are consistent with our model of HCMV infection of monocytes, in which we observe an induction of enhanced monocyte motility and migration following viral binding to EGFR and integrins on the surface of monocytes (22, 25, 26, 51). We wanted to investigate a potential role for STAT1 in HCMV-induced monocyte motility. Briefly, monocytes were transfected with STAT1-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) or nonspecific control siRNA for 24 h prior to mock or HCMV infection. Western blot analyses were performed to confirm a decrease in STAT1 expression (Fig. 6A). We utilized our monocyte motility assay (51, 87) to compare the relative motility of untransfected monocytes and monocytes transfected with control siRNA with that of monocytes transfected with STAT1-specific siRNA (Fig. 6B). Following treatment, monocytes were plated on colloidal gold-covered coverslips and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Images of individual cells were taken at a magnification of ×200, and the zone of clearing of the colloidal gold particles around individual monocytes was measured with Metamorphosis software. These measurements were used to determine the fold change in monocyte motility (compared to mock-infected, untransfected monocytes) (Fig. 6B). We observed an ∼1.8-fold increase in motility of HCMV-infected monocytes compared to uninfected monocytes. Motility was significantly reduced (P < 0.005; determined by Student's t test) when HCMV-infected monocytes were transfected with STAT1-specific siRNA but not when they were transfected with control siRNA, suggesting that STAT1 helps promote efficient motility of infected monocytes.

FIG 6.

STAT1 is required for HCMV-induced monocyte motility. (A and B) Monocytes were transfected with nonspecific control siRNA or STAT1-specific siRNA for 24 h and then mock or HCMV infected for 24 h. (A) Protein lysates were harvested at 24 hpi for Western blot analysis utilizing antibodies specific for total STAT1 or actin as a loading control. (B) At the time of infection, monocytes were plated on colloidal gold-coated coverslips (87) and incubated at 37°C. At 24 hpi, images of individual monocytes were taken at a magnification of ×200 under bright-field microscopy. Metamorphosis software was used to measure the zone of clearing in the colloidal gold around individual monocytes. The average area cleared by individual cells from each sample was used to determine the fold change in monocyte motility compared to mock-infected monocytes. Results are plotted as the mean fold changes (±SEM) from 3 individual experiments. Student's t tests were performed, and a P value of <0.05 (indicated by an asterisk) was used to determine statistical significance between samples.

We also observed a statistically significant (P = 0.049) decrease in the motility of uninfected monocytes transfected with STAT1-specific siRNA compared to uninfected monocytes transfected with control siRNA. However, transfection of these cells with a control siRNA resulted in a slight (yet statistically nonsignificant) increase in monocyte motility (1.2-fold change) over uninfected untransfected monocytes. There was also a statistically nonsignificant decrease in monocyte motility in uninfected monocytes transfected with STAT1-specific siRNA compared to that of uninfected, untransfected monocytes (0.8-fold change).

STAT1 is required for HCMV-induced monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization.

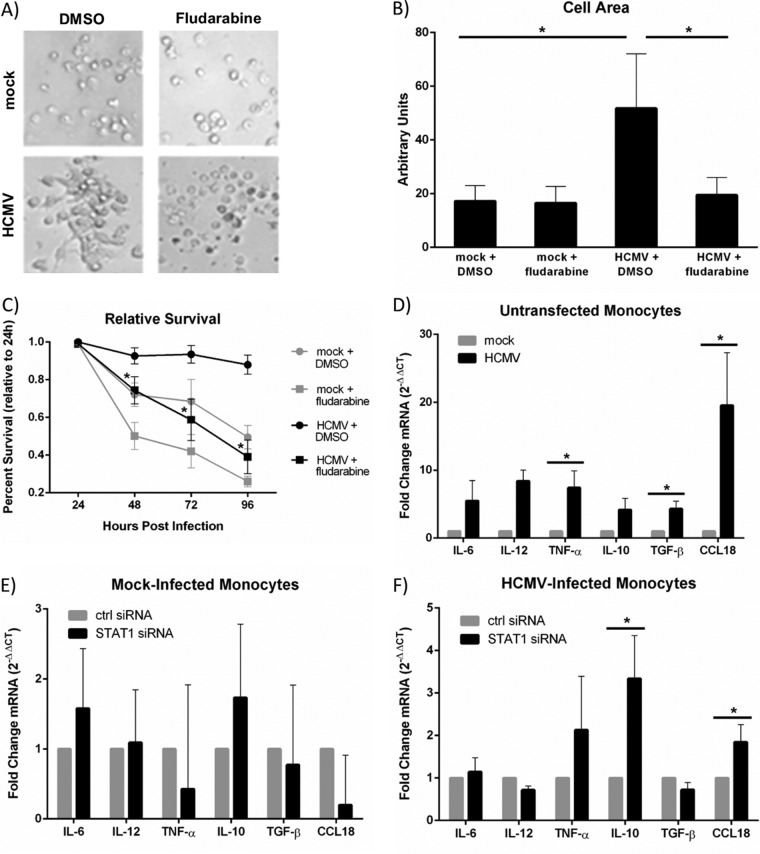

We previously showed that HCMV induces the differentiation of infected monocytes toward a proinflammatory macrophage phenotype (31, 32, 34), consistent with the altered regulation of genes associated with cellular maturation and differentiation in our transcriptome analysis at 24 hpi (Table 1). STAT1 has recently been implicated in the differentiation process of monocytes (61, 62, 88) and in the proinflammatory polarization of macrophages (89). To test a potential role for STAT1 in the differentiation of HCMV-infected monocytes, we first analyzed microscopy images of monocytes that were pretreated with fludarabine, a potent STAT1 inhibitor (90), or a dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solvent control and then mock infected or HCMV infected for 24 hpi. These analyses revealed that HCMV-infected monocytes displayed characteristic cellular morphological changes associated with monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, including cellular enlargement and elongation (12, 35), compared to their mock-infected counterparts at 24 hpi; however, in the absence of STAT1, the morphology of HCMV-infected monocytes resembled that of mock-infected monocytes (Fig. 7A). These qualitative observations were confirmed quantitatively by measurement of cellular areas of the different treatment groups (Fig. 7B). Together, these data suggest that STAT1 may be required for the overall differentiation of infected monocytes into long-lived macrophages. Because we previously showed that HCMV-infected monocytes undergoing monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation possess a survival advantage over their uninfected, nondifferentiating counterparts (12, 21, 30, 35; reviewed in reference 31), we next asked whether the presence of STAT1 affected the survival of monocytes during infection. We performed 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays to compare the survival rates of uninfected and HCMV-infected monocytes treated with fludarabine or a DMSO solvent control. We found that the viability of mock-infected monocytes gradually declined over the course of 4 days while the viability of HCMV-infected monocytes remained fairly stable (Fig. 7C). However, in the presence of fludarabine, HCMV-infected monocytes showed evidence of cell death similar to that seen in uninfected monocytes, suggesting that STAT1 is required for the enhanced survival of infected cells (Fig. 7C). We also observed a small decrease in the viability of mock-infected monocytes in the presence of fludarabine, suggesting that STAT1 may play a minor role in regulating the survival of uninfected monocytes and/or that the pharmacological inhibitor, fludarabine, may be slightly toxic to uninfected primary monocytes. When combined with our morphological analysis of HCMV-infected monocytes in the presence or absence of fludarabine, these data suggest that the prolonged survival of infected monocytes, which occurs during HCMV-induced monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, is dependent on the expression and activation of STAT1.

FIG 7.

STAT1 is required for HCMV-induced monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization. (A) Monocytes were pretreated with DMSO control or fludarabine (1 μM) for 1 h and then mock or HCMV infected. Monocytes were then added to fibronectin-coated plastic dishes and incubated at 37°C for 24 hpi. Images were taken at a magnification of ×200 with bright-field microscopy. (B) ImageJ software was used to measure the areas (in arbitrary units) of individual cells from the bright-field microscopy images. Results are plotted as means ± SEM. Student's t tests were performed, and a P value of <0.05 (indicated by asterisks) was used as a measure of statistical significance between samples. (C) Monocytes were pretreated with a DMSO solvent control or 1 μM fludarabine for 1 h. Monocytes were then mock or HCMV infected for 24 to 96 hpi. An MTT assay was performed each day in triplicate for each sample. Results are plotted as the mean percent survival ± SEM for each sample from 3 representative donors. Percent survival was calculated as the ratio of mean absorbance values for each time point to mean absorbance values for day zero. Student's t tests were performed, and a P value of <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance between samples. (D to F) Monocytes were transfected with STAT1-specific siRNA or nonspecific siRNA control (E, F) or left untransfected (D) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Monocytes were then mock or HCMV infected for 24 h. At 24 hpi, RNA was harvested and converted to cDNA. RT-qPCR was performed using primers specific for IL-6, IL-12, or TNF-α (M1-associated genes) or for IL-10, TGF-β, or CCL18 (M2-associated genes). 18S rRNA was used for normalization. Results are plotted as average fold changes (2−ΔΔCT) ± SEM for samples from 5 individual donors. Student's t tests were performed, and a P value of <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance between samples.

Our laboratory has shown that HCMV induces an M1-biased polarization phenotype during HCMV-induced monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation (31, 32, 34). Comparison of the expression of key M1-associated genes (interleukin-6 [IL-6], IL-12, and TNF-α) and M2-associated genes (IL-10, transformation growth factor beta [TGF-β], and CCL18) in mock-infected versus HCMV-infected monocytes at 24 hpi by quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) revealed that HCMV caused the upregulation of both M1- and M2-associated genes (Fig. 7D). Because STAT1 was previously shown to be critical for M1 macrophage polarization in response to LPS or IFN-γ (89), we next tested whether HCMV-induced STAT1 expression played a role in the macrophage polarization phenotype observed in HCMV-infected monocytes. Comparison of the expression of M1- and M2-associated genes in uninfected monocytes transfected with nonspecific control siRNA versus STAT1-specific siRNA revealed that STAT1 does not play a significant role in the basal expression of the M1- or M2-associated genes examined in naive monocytes (Fig. 7E). Surprisingly, comparison of the expression of M1-associated genes in HCMV-infected monocytes transfected with nonspecific control siRNA versus STAT1-specific siRNA revealed no significant role for STAT1 in the upregulation of the M1-associated genes tested (Fig. 7F). However, comparison of the expression of M2-associated genes in HCMV-infected monocytes transfected with nonspecific control siRNA versus STAT1-specific siRNA revealed that in the absence of STAT1, the expression of IL-10 and CCL18, two genes associated with M2 macrophage phenotypes, were significantly increased (Fig. 7F). We also have unpublished data showing that when LPS (M1), phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (M2), and HCMV treatments are compared, there are differences in M1/M2 cytokine expression: LPS and PMA treatment showed patterns of gene expression distinct from that seen following HCMV infection, consistent with the studies discussed above. The role of STAT1 signaling was complex with loss of STAT1 causing a downmodulation in some cases and upregulation in other cases. We argue that differences in STAT1 expression, patterns of phosphorylation, and regulation with other factors are in play in our system and that these events differ under different monocyte/macrophage stimuli. A more detailed experimentation into these complexities is under way in the laboratory. These data suggest that STAT1 controls select patterns of gene expression during HCMV infection, perhaps as a mechanism to skew the polarization of infected monocytes toward the appropriate M1/M2 macrophage phenotype that we have observed during infection (31–33).

DISCUSSION

Infected peripheral blood monocytes serve as “Trojan horses” to carry HCMV out of the bloodstream and into the surrounding organ tissues—a process critical for the dissemination of the virus following primary infection (3, 17, 31). We and others have shown that viral gene expression does not occur at detectable levels in infected monocytes until more than 2 weeks postinfection, when monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation enables viral replication and the production of viral progeny (12, 21, 91–93). Conflicting reports have shown low levels of viral gene expression in similar infection models (94, 95), although these gene expression levels do not appear to trigger the full replicative cycle. We have shown that during this period of quiescent infection, HCMV is able to trigger multiple proinflammatory changes in infected monocytes via ligand activation of EGFR and integrins during viral binding and that these changes promote viral dissemination and persistence (12, 22, 25, 26, 51). Specifically, HCMV drives the enhanced motility and transendothelial migration of infected monocytes, which promotes the movement of infected cells out of the bloodstream and into peripheral organ tissues (12, 25, 26, 51), while simultaneously prolonging the survival of infected monocytes and driving their differentiation and polarization toward a proinflammatory M1 macrophage, although with some M2 characteristics (12, 21, 30–32, 34). In this study, we show that HCMV induces the expression and activation of the traditionally antiviral protein, STAT1, through a nontraditional cascade involving EGFR and integrin signaling, in order to utilize the cell regulatory functions of STAT1 to promote the changes necessary for the spread and persistence of HCMV during infection of monocytes.

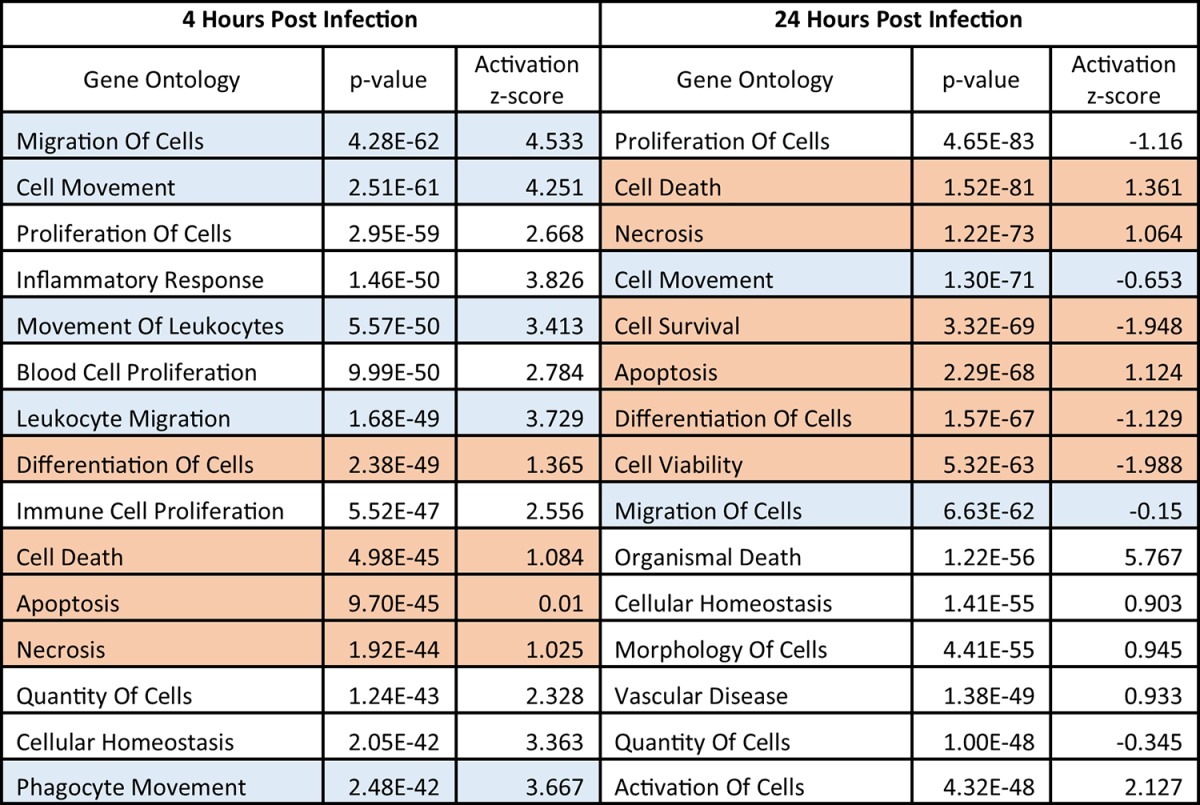

From our data, we have constructed a model depicting the HCMV-induced biphasic activation of STAT1 and its downstream functional consequences (Fig. 8). Following binding to EGFR and integrins during viral entry, STAT1 is rapidly phosphorylated at Y701 to promote the expression of a specific subset of STAT1-dependent ISGs. Early activation of STAT1 results in increased monocyte motility, which would drive transendothelial migration of infected cells into the surrounding tissues. HCMV continues to trigger extended signaling through EGFR and integrins following entry, and STAT1 undergoes a second peak of phosphorylation at 24 hpi, this time at Y701 and S727. The second activation of STAT1 promotes the transcription of a different subset of STAT1-dependent ISGs. This late transcriptional profile promotes monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and helps to shape the polarization of infected cells toward an M1-like macrophage by suppressing key M2-associated genes.

FIG 8.

Our model of STAT1's role in the regulation of gene expression and functional changes at early and later times postinfection in HCMV-infected monocytes. The binding of HCMV glycoproteins to EGFR and integrins on the surface of monocytes prior to infection initiates EGFR- and integrin-dependent signaling cascades that induce the rapid phosphorylation of STAT1 at Y701 and a decrease in the phosphorylation of STAT1 at S727. This phosphorylation at Y701 occurs within 5 mpi and peaks at ∼30 mpi, before decreasing and returning to basal levels by ∼1 hpi. Y701-phosphorylated STAT1 is translocated into the nucleus, where it can bind to DNA and promote the transcription of a subset of STAT1-dependent ISGs, some of which may play a role in the regulation of HCMV-induced enhanced monocyte motility. Following viral entry into monocytes, EGFR and integrin signaling continues to fire for some time, as EGFR and integrin signaling from around 2 to 8 hpi is required for the late phase of STAT1 activation (characterized by increases in STAT1 phosphorylation at Y701 and S727) at 24 hpi. The late phase of STAT1 activation induces nuclear translocation of both Y701-phosphorylated and S727-phosphorylated STAT1, allowing STAT1 to bind to DNA and induce the transcription of another subset of STAT1-dependent ISGs. The late activation of STAT1 is required for HCMV-induced monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and is associated with the inhibition of two M2-associated genes, encoding IL-10 and CCL18, presumably through repression by one or more STAT1-dependent gene(s), which helps to skew the polarization of infected monocytes toward a more M1-like phenotype. Overall, HCMV induces the activation of STAT1 in two distinct phases in order to harness the activity of this powerful transcriptional regulator to promote the changes required for viral spread and persistence.

Our transcriptome analyses indicated that HCMV-induced gene expression changes are different at 4 hpi and 24 hpi, with the early transcriptional changes (4 hpi) regulating cellular activation and cellular movement and the later transcriptional changes (24 hpi) regulating cellular survival and differentiation (Table 1). These distinct transcriptional profiles hint at a biphasic response to HCMV infection, whereby the cellular environment of an infected monocyte must shift from primary activation aimed at enhanced cellular motility and migration out of the bloodstream toward a dedicated cell survival and macrophage differentiation program to support viral replication and spread to organ tissues. Further, our new data show that STAT1 may play a role in bridging the transition from the early activated monocyte phenotype to the sustained maintenance of cellular differentiation that occurs later in infection. We propose that STAT1 may function as a regulator of cellular transcription in the infected monocyte, promoting distinct early and late transcription programs dependent on the phosphorylation/activation triggered by EGFR/integrin signaling.

The transcriptional changes that are unique at 4 hpi are mostly associated with the activation of cellular movement (Table 1), and our data suggest that STAT1 is required, at least in part, for HCMV-induced monocyte motility (Fig. 6B). Because we have shown that HCMV-induced monocyte motility begins as early as 6 hpi (12, 25), the STAT1-dependent transcriptional changes associated with enhanced monocyte motility likely occur downstream of the early (30 mpi) activation of STAT1. Therefore, we suggest that the transient, early phosphorylation of STAT1 may serve to induce the early activation of infected monocyte motility through the induction of a specific subset of STAT1-dependent ISGs. STAT1 has been shown to play either an inhibitory or an activating role in monocyte motility and migration, depending on the activating stimulus. For example, STAT1 was shown to inhibit monocyte migration in the context of IFN-γ (96, 97) but was shown to enhance the migration of HIV-infected monocytes through the blood-brain barrier in a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent manner (98–100). STAT1 may also play a role in the migration of other cell types, in addition to monocytes. For example, STAT1 was shown to be activated by EGFR and to be required for the motility of esophageal keratinocytes (101). STAT1 was also shown to be activated downstream of integrin-mediated focal adhesion kinase activation and to be required for the adhesion and migration of fibroblasts (102). Our data show that the early activation of STAT1 requires EGFR and integrin signaling (Fig. 4C) and that HCMV-induced motility is enhanced by EGFR (22), integrin (51), and STAT1 signaling (Fig. 6B). These data imply that the early activation of STAT1 may help link viral activation of EGFR and integrin signaling pathways with the downstream functional consequence of enhanced motility observed in infected monocytes.

The later, sustained activation of STAT1 through 24 hpi (Fig. 2A) suggests that STAT1 may also induce transcriptional changes beyond 4 hpi. Indeed, our transcriptome analyses suggested that the HCMV-induced expression of STAT1-associated ISGs was altered at 24 hpi compared to mock-infected monocytes and that the profile of STAT1-associated ISG expression was different from that seen at 4 hpi (Fig. 5). Specifically, we see high levels of regulation among genes associated with cellular survival/apoptosis and cellular differentiation. Compared to the strong upregulation of motility-associated genes (as indicated by Z-scores greater than 1.97) at 4 hpi, we see a mix of upregulation and downregulation of gene products associated with apoptosis and differentiation (as indicated by Z-scores that are closer to zero) at 24 hpi. This is not a surprising finding, given that cellular control of both apoptosis and differentiation requires a finely tuned balance of apoptotic versus antiapoptotic factors, as well as differentiation/polarization factors (e.g., those more associated with either an M1 or M2 macrophage phenotype). Functionally, our data suggest that STAT1 is required for the overall differentiation and prolonged survival of HCMV-infected monocytes (Fig. 7A to C). Furthermore, we now show that STAT1 may help to shape the HCMV-induced macrophage phenotype by inhibiting the overexpression of at least two M2-associated genes, IL-10 and CCL18 (Fig. 7F), which we suggest may allow the virus to promote a more M1-like phenotype. Interestingly, we found that STAT1 did not play a significant role in the expression of the common HCMV-induced M1-associated proinflammatory genes, IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α (Fig. 7F), despite the documented role of STAT1 in the expression of these M1-associated genes during IFN-γ or LPS treatment (89). These data suggest that the macrophage polarization-associated transcriptional activity of STAT1 in HCMV-infected monocytes is likely distinct from that of IFN-γ- or LPS-treated monocytes, and this may therefore provide a partial explanation for our previous findings that HCMV-infected monocytes possess a unique transcriptional profile with regard to M1/M2 polarization following monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation (31, 32, 34). In support of this notion, various macrophage-polarizing stimuli induce different profiles of STAT1 expression and phosphorylation at 24 h posttreatment. For example, HCMV induces robust STAT1 phosphorylation at Y701 and S727 at 24 hpi (Fig. 2A and B and 3B). LPS also induces an increase in Y701 and S727 phosphorylation of STAT1, although not to the extent of that seen in HCMV infection, and IFN-α induces only a slight increase in Y701 phosphorylation but not S727 phosphorylation (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and M-CSF (growth factors known to induce the polarization of monocytes toward an M1 and M2 macrophage phenotype, respectively) induce only a minimal S727 phosphorylation of STAT1 with no Y701 phosphorylation at 24 hpi. Because the phosphorylation of STAT1 in conjunction with the formation of distinct STAT dimers provides the basis for the specificity of STAT1's DNA binding and transcriptional activities, the data suggest that STAT1's transcriptional regulation of various polarization-associated genes may be different under different stimuli (i.e., HCMV, LPS, PMA, M-CSF, and GM-CSF).

Mechanistically, our data suggest that STAT1's potentially unique profile of downstream ISGs in HCMV-infected monocytes (compared to IFN or LPS stimulation) may be attributed to the nontraditional signaling cascade involved in the biphasic activation of STAT1 during infection. Although the activation of STAT1 is known to occur primarily downstream of IFN signaling (as is the case during IFN or LPS stimulation), our data indicate that the phosphorylation of STAT1 in HCMV-infected monocytes occurs independent of IFN signaling (Fig. 3) and instead occurs downstream of EGFR and integrin signaling at both the early (30 mpi) and late (24 hpi) phases of activation (Fig. 4C and F). Notably, our data indicate that the signaling from EGFR and integrins that triggers the early and late phases of STAT1 activation may be molecularly independent. Our data suggest that the early activation of STAT1 (at 30 mpi) is not sufficient for the late activation of STAT1 (at 24 hpi) (Fig. 4F), which supports independent functional roles for the early and late activation of STAT1. Moreover, these data indicate that even after viral entry, EGFR and integrin signaling continue to fire (either through sustained viral binding to these receptors or through some type of HCMV-induced feedback mechanism). This finding is consistent with our microarray data showing that EGFR- and integrin-dependent transcriptional changes in HCMV-infected monocytes/macrophages persist for at least 2 weeks postinfection (Cieply et al., unpublished). This chronic signaling through EGFR and integrins may provide a potential mechanism for the similar biphasic and chronic activation of other signaling molecules in HCMV-infected monocytes, such as Akt (25), and for our laboratory's data indicating a requirement for EGFR and/or integrin signaling in the expression of HCMV-induced antiapoptotic molecules between 24 and 96 hpi in infected monocytes (21, 30). We suggest that the activation of STAT1 might be critical for the overall persistence strategy of HCMV, particularly within infected monocytes.

Our data indicate that STAT1 serves a proviral function by promoting enhanced monocyte motility and helping to regulate differentiation toward a more M1-like macrophage. However, due to STAT1's well-established role in antiviral responses, the activation of STAT1 could potentially be a double-edged sword in that it promotes proviral monocyte biological changes but may also inhibit viral replication. This is illustrated in a study by Harwardt et al., in which the virus rewires STAT signaling in infected fibroblasts (103). In this study, HCMV IE1 binds to STAT3, depleting cytoplasmic stores of STAT3 that would become activated by JAK kinases following IFN signaling. Depletion of activated STAT3 leads to the activation of STAT1 by JAK kinases instead, effectively rerouting IL-6/STAT3 upstream signaling to IFN-γ/STAT1 downstream signaling. Although the low levels of immediate early (IE) gene expression observed by other groups (94, 95) leave open the possibility that a similar mechanism could contribute to the activation of STAT1 in infected monocytes, this would certainly not account for all of the STAT1 activation, as IE expression detected in these cells is much lower than that detected in fibroblasts. In our model, we see that primary infection of monocytes results in a 2-week period of quiescence during which IE (IE1, IE2, UL36, UL37, IE2-86) and L (gH) genes and proteins are not detectable by RT-PCR and immunofluorescent staining, respectively (12, 21). We suggest that HCMV regulates STAT1's phosphorylation (and thus, biological activity) primarily by utilizing an EGFR- and integrin-dependent activation cascade (Fig. 4C and E to G), rather than the traditional IFN-dependent pathway (Fig. 3) or the IE-induced rewiring of JAK/STAT signaling (103). Perhaps this unique regulation of STAT1 activation helps to overcome the hurdle of STAT1's potential antiviral activity while helping to regulate monocyte motility and differentiation.

A number of studies support the notion that STAT1 could play a dual role during HCMV infection of monocytes by promoting a proviral macrophage phenotype while also mediating antiviral immune evasion (57, 92, 104). In one model of HCMV latency/reactivation, the generation of replication-permissive macrophages requires that monocytes be treated with IFN-γ (a known activator of STAT1 signaling) from stimulated T cells (57, 104). In using this model, the authors discovered that stimulation of monocytes with IFN-γ to promote differentiation created a macrophage that is resistant to the antiviral effects of further IFN-γ treatment following infection with HCMV (57). We suggest that the observed IFN-γ-induced monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and, later, the conferred antiviral resistance in the authors' system may be dependent on the activation of STAT1. In support of this theory, a more recent study using GM-CSF-treated primary monocytes as a model for HCMV latency again demonstrated the ability of HCMV to induce a monocyte/macrophage phenotype that is resistant to the effects of exogenous IFN, as IFN-β- and IFN-γ-induced activation of STAT1 was inhibited in latently infected monocytes at 72 hpi (92). Although the activation of STAT1 within 24 hpi (as we have reported here) was not addressed in this study, when combined with our current studies and with the previous reports that IFN-γ pretreatment promotes a macrophage phenotype that is resistant to the antiviral effects of secondary treatment with IFN in HCMV-infected macrophages (57), these findings support that the initial activation of STAT1 within 24 hpi in target monocytes may allow HCMV to promote a monocyte/macrophage phenotype that not only later supports viral spread and persistence but also becomes resistant to the antiviral effects of IFN and potentially other stimulatory molecules.

We propose that the biphasic pattern of STAT1 phosphorylation (Y701 early; Y701 and S727 late) in HCMV-infected monocytes may serve as a mechanism for STAT1-mediated antiviral immune evasion. It has already been shown experimentally that phosphorylation of STAT1 at S727 is required to induce an antiviral state in response to type I IFN signaling (78). These findings are corroborated by clinical studies of human subjects diagnosed with Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease. These patients have an autosomal dominant mutation of STAT1 that abolishes (L706S [105]) or severely impairs (K637E and K673R [106]) Y701 phosphorylation, resulting in impaired function of STAT1 in response to mycobacterial infection. However, these patients were shown to have normal antiviral immune responses (105, 106) and normal S727 phosphorylation (105), suggesting that S727 phosphorylation may be critical for the regulation of antiviral responses, while Y701 phosphorylation may be critical for the proinflammatory activation associated with antibacterial responses. Therefore, by promoting the early nuclear translocation of STAT1 phosphorylated at only Y701 and not S727, HCMV may be able to quickly dictate the expression of key early ISGs that are required for proinflammatory monocyte activation, while avoiding antiviral immune responses. Our various transcriptomic studies support this selectivity in proinflammatory gene expression and the lack of a strong antiviral gene expression (22, 32–34, 51).

In summary, these studies reveal that HCMV regulates specific changes in cellular signaling and transcription in infected monocytes by controlling the activation of STAT1. By inducing two distinct phases of STAT1 activation, HCMV is able to utilize the transcriptional activity of STAT1 to promote the expression of select subsets of STAT-dependent ISGs, which promote a proinflammatory phenotype that is required for viral spread and persistence. Furthermore, our data indicate that HCMV can hijack the activity of an antiviral signaling protein through a unique activation cascade utilizing EGFR and integrin signaling to promote the proviral changes that are critical for viral success in infected hosts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HCMV culture and infection.

Human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts were infected at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1, with HCMV strain Towne/E (passage 40) and were cultured in 4% fetal bovine serum (FBS) Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Cellgro; Mediatech, Herndon, VA). HCMV Towne/E was purified by sucrose gradient purification and then resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Cellgro). Human peripheral blood monocytes were infected with HCMV Towne/E at an MOI of 5 for all experiments or treated with an equal volume of RPMI 1640 (Cellgro) for mock infection.

Human peripheral blood monocyte isolation.