ABSTRACT

Influenza viruses of the H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2 subtypes have caused previous pandemics. H2 influenza viruses represent a pandemic threat due to continued circulation in wild birds and limited immunity in the human population. In the event of a pandemic, antiviral agents are the mainstay for treatment, but broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) may be a viable alternative for short-term prophylaxis or treatment. The hemagglutinin stem binding bNAbs CR6261 and CR9114 have been shown to protect mice from severe disease following challenge with H1N1 and H5N1 and with H1N1, H3N2, and influenza B viruses, respectively. Early studies with CR6261 and CR9114 showed weak in vitro activity against human H2 influenza viruses, but the in vivo efficacy against H2 viruses is unknown. Therefore, we evaluated these antibodies against human- and animal-origin H2 viruses A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 (H2N2) (AA60) and A/swine/MO/4296424/06 (H2N3) (Sw06). In vitro, CR6261 neutralized both H2 viruses, while CR9114 only neutralized Sw06. To evaluate prophylactic efficacy, mice were given CR6261 or CR9114 and intranasally challenged 24 h later with lethal doses of AA60 or Sw06. Both antibodies reduced mortality, weight loss, airway inflammation, and pulmonary viral load. Using engineered bNAb variants, antibody-mediated cell cytotoxicity reporter assays, and Fcγ receptor-deficient (Fcer1g−/−) mice, we show that the in vivo efficacy of CR9114 against AA60 is mediated by Fcγ receptor-dependent mechanisms. Collectively, these findings demonstrate the in vivo efficacy of CR6261 and CR9114 against H2 viruses and emphasize the need for in vivo evaluation of bNAbs.

IMPORTANCE bNAbs represent a strategy to prevent or treat infection by a wide range of influenza viruses. The evaluation of these antibodies against H2 viruses is important because H2 viruses caused a pandemic in 1957 and could cross into humans again. We demonstrate that CR6261 and CR9114 are effective against infection with H2 viruses of both human and animal origin in mice, despite the finding that CR9114 did not display in vitro neutralizing activity against the human H2 virus. These findings emphasize the importance of in vivo evaluation and testing of bNAbs.

KEYWORDS: H2 influenza virus, broadly neutralizing antibodies, prophylaxis, in vivo evaluation, antibody function, influenza, influenza vaccines

INTRODUCTION

Influenza pandemics occur when an antigenically novel subtype from the avian reservoir or pigs is introduced and spreads in a susceptible human population. In the last century, H1N1, H2N2, and H3N2 influenza A viruses have caused pandemics. After becoming established in humans, pandemic viruses continue to circulate and cause annual/seasonal epidemics. H2N2 influenza viruses initiated a pandemic in 1957 and circulated for 11 years, causing an estimated 2 million deaths worldwide (1). In 1968, an H3N2 virus replaced H2N2 viruses and, as a result, individuals born after 1968 are susceptible to infection with H2 influenza viruses.

Influenza viruses of the H2 subtype continue to circulate in wild birds (2–6), and in 2006, an H2N3 virus (A/swine/MO/4296424/2006) was isolated from pigs displaying clinical illness (7). This virus caused disease in mice and pigs following intranasal inoculation (7–9), and characterization of several additional avian H2N2 viruses demonstrated that many isolates could replicate in mice and in human bronchial epithelial cells (9, 10). In contact transmission studies, both avian H2 and swine H2N3 viruses transmitted efficiently in ferrets, and sequence analysis indicated that these viruses rapidly acquire mutations in the hemagglutinin (HA) receptor-binding site (7, 11). As a result of the limited population immunity against H2 influenza and the continued circulation of H2 influenza viruses in animal reservoirs, this subtype has the potential to reemerge and initiate a pandemic.

The neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir and zanamivir are the first line of treatment for severe influenza; however, broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (bNAbs) may be a useful adjunct. Several bNAbs have been isolated from immortalized human B cells and phage display libraries (12–14). In particular, CR6261 was isolated from phage display libraries derived from seasonal influenza vaccinees. This antibody showed broad in vitro neutralizing activity against H1, H2, H5, H6, H8, and H9 influenza subtypes. However, within the H2 subtype, CR6261 showed reduced or limited neutralizing activity against human isolates compared to avian viruses (14). In prophylaxis studies in mice, CR6261 protected against death and weight loss following lethal H1N1 and H5N1 challenge (14). When administered as a therapy 4 days postinfection, CR6261 protected against lethal H1N1 challenge and enhanced survival (40% versus 0%) following H5N1 challenge (15). In subsequent studies in ferrets, CR6261 administered prophylactically or as a therapy 1 day postinfection protected against mortality and reduced weight loss, viral replication, and pulmonary pathology in H5N1-challenged animals (16).

To identify a bNAb capable of inhibiting both influenza A and B viruses, a comparable library was panned with recombinant influenza A and B HA proteins. This led to the identification of the bNAb CR9114 (13), which displayed binding to representative viruses from 14 influenza A subtypes and influenza B viruses but had reduced binding to human H2N2 viruses (13). In vitro CR9114 was only able to neutralize H1N1 and H3N2 viruses; however, in prophylaxis studies in mice, CR9114 protected against lethal challenge with H1N1, H3N2, and influenza B viruses (13). Subsequently, the crystal structures of CR6261 bound to H1 and H5 HA and CR9114 bound to H3, H5, and H7 HA were solved. These structures revealed that both antibodies bind the stem region of the HA molecule (13, 17).

Importantly, while CR6261 displayed reduced in vitro activity and CR9114 had limited binding to human H2 viruses, neither antibody has been evaluated for in vivo activity against H2 influenza viruses. Thus, we investigated the prophylactic efficacy and protective mechanisms in mice of CR6261 and CR9114 against A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 (H2N2) (designated AA60) and A/swine/MO/4296424/2006 (H2N3) (designated Sw06) as representative human- and animal-origin H2 viruses.

RESULTS

CR6261 and CR9114 protect against lethal H2 influenza disease despite discrepancies in in vitro neutralization capacity.

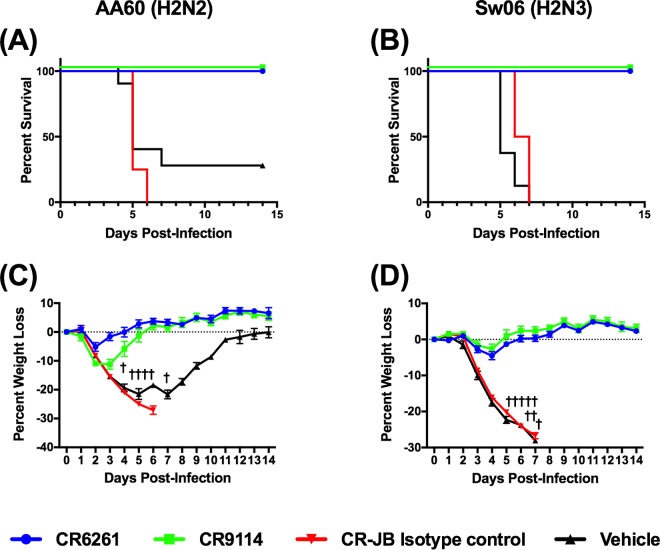

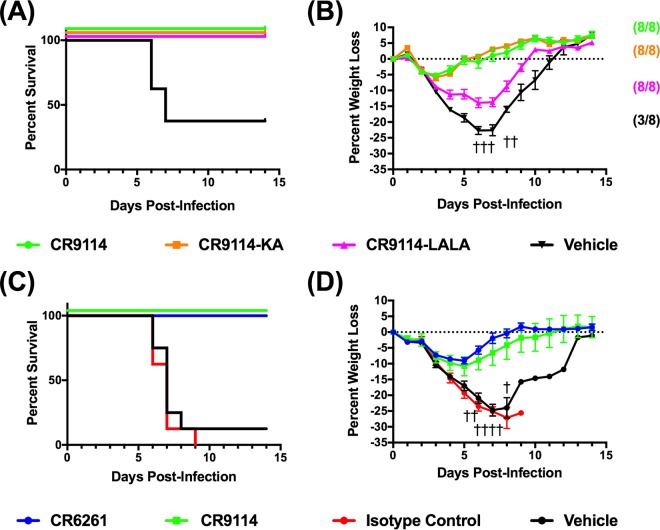

Based on early studies that showed reduced in vitro activity and/or binding of CR6261 and CR9114 against H2 influenza viruses (13, 14), we performed microneutralization assays with antibodies against both AA60 and Sw06 (Table 1). CR6261 neutralized AA60 and Sw06, while CR9114 neutralized Sw06 but not AA60 (limit of the assay, 500 μg/ml). To determine if the in vitro neutralizing activity of CR6261 and CR9114 was indicative of in vivo efficacy, we performed prophylaxis studies in BALB/c mice. We initially evaluated both antibodies and CR-JB, an isotype control directed toward the rabies virus glycoprotein, at a high dose of 15 mg/kg of body weight. Mice were administered the antibodies via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection and challenged 24 h later with 25 median mouse lethal doses (MLD50) of AA60 or Sw06 virus. As shown in Fig. 1A and B, all of the mice treated with CR6261 and CR9114 survived both AA60 and Sw06 virus challenge and exhibited transient weight loss with recovery by day 6 postinfection (Fig. 1C and D). In contrast, all mice treated with the isotype control or with the vehicle (antibody dilution buffer) lost weight, and all of the isotype control-treated mice succumbed to infection or reached clinical endpoint (>25% weight loss) and were euthanized by day 7 postinfection. Of the vehicle-treated mice, 6 of 8 and 8 of 8 mice challenged with AA60 and Sw06, respectively, either succumbed to infection or reached clinical endpoint by day 7 postinfection.

TABLE 1.

Evaluation of CR6261 and CR9114 in neutralization assays against H2 influenza viruses

| Antibody | Concn required for neutralization (μg/ml) of: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant A/Ann Arbor/6/60 (H2N2)a | A/swine/MO/4296424/06 (H2N3) | |

| CR6261 | 39.4 | 176.8 |

| CR9114 | >500 | 49.6 |

| KA-CR9114 | >500 | 31.25 |

| LALA-CR9114 | >500 | 31.25 |

>500 denotes that we did not detect neutralizing activity.

FIG 1.

Prophylactic efficacy of high-dose CR6261 and CR9114 against H2 influenza virus challenge in BALB/c mice. To determine if bNAbs protected against H2 influenza virus challenge, BALB/c mice (n = 8/group) were administered CR6261, CR9114, or CR-JB (isotype control) at a dose of 15 mg/kg, or vehicle (antibody dilution buffer), and were challenged with 25 MLD50 of A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 (H2N2) or A/swine/MO/42964624/2006 (H2N3). (A and B) Percent survival (A) and percent weight loss (C) (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) after A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 (H2N2) challenge. (B and D) Percent survival (B) and percent weight loss (D) (mean ± SEM) after A/swine/MO/42964624/2006 (H2N3) challenge. Daggers represent a vehicle-treated mouse that succumbed to infection or that reached endpoint.

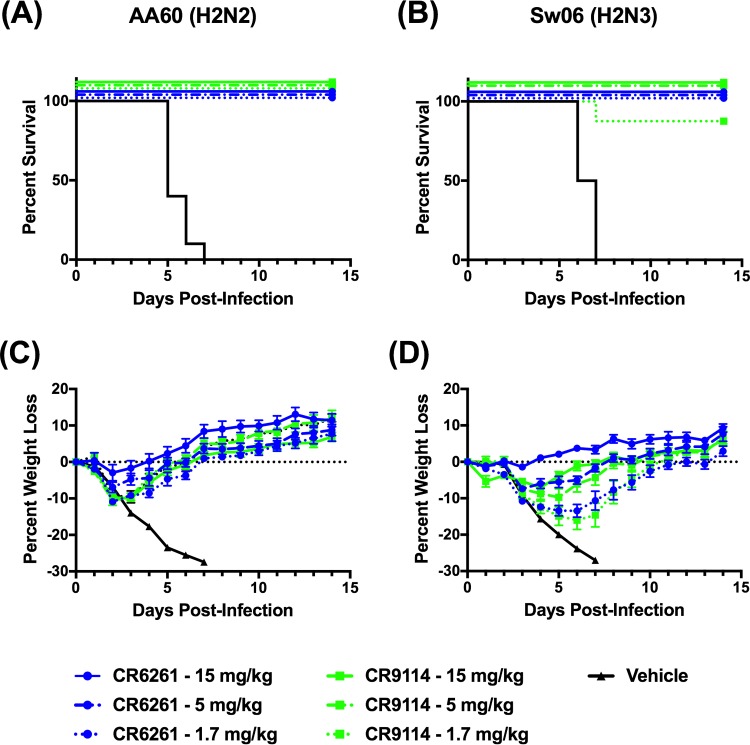

Based on these results, we performed dose-response studies to evaluate the protection conferred by lower doses of CR6261 and CR9114. Thus, mice were prophylactically administered 1.7, 5, or 15 mg/kg of CR6261 or CR9114 and were challenged with both viruses. For these studies, we omitted the isotype control, as it failed to induce protection at a dose of 15 mg/kg. Shown in Fig. 2A and C are the survival and weight loss results for mice challenged with AA60. All mice treated with the vehicle control lost weight rapidly and succumbed to infection or reached endpoint by day 7. In antibody-treated mice at all doses of CR6261 and CR9114, all mice survived challenge and the percent weight loss decreased with increasing antibody dose (Fig. 2C). These results were unexpected because we had anticipated reduced protection in CR9114-treated mice due to its lack of in vitro neutralizing activity against AA60. In the context of Sw06 challenge (Fig. 2B and D), all vehicle control animals lost weight and reached clinical endpoint by day 7. Mice treated with either bNAb were protected against mortality at doses of 5 and 15 mg/kg. At the lowest dose of 1.7 mg/kg, CR6261 prevented mortality and a single animal treated with CR9114 succumbed to infection. As observed following AA60 challenge, there was a reduction in weight loss with increasing antibody dose (Fig. 2D). Collectively, these findings indicate that prophylaxis with CR6261 and CR9114 protected mice against lethal H2 influenza virus challenge irrespective of the in vitro neutralizing activity of the antibodies.

FIG 2.

Prophylactic efficacy of decreasing doses of CR6261 and CR9114 against H2 influenza virus challenge in BALB/c mice. To evaluate efficacy over a range of antibody doses, BALB/c mice were administered CR6261 or CR9114 at doses of 0, 1.7, 5, and 15 mg/kg and were challenged with 25 MLD50 of H2 influenza viruses. (A and C) Percent survival (A) and percent weight loss (C) (mean ± SEM) after A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 (H2N2) challenge. (B and D) Percent survival (B) and percent weight loss (D) (mean ± SEM) after A/swine/MO/42964624/2006 (H2N3) challenge. Eight to 10 animals were used in each group, and animals were monitored for 14 days after virus challenge.

Prophylaxis with CR6261 or CR9114 decreased viral load, altered antigen distribution, and reduced the severity of airway inflammation.

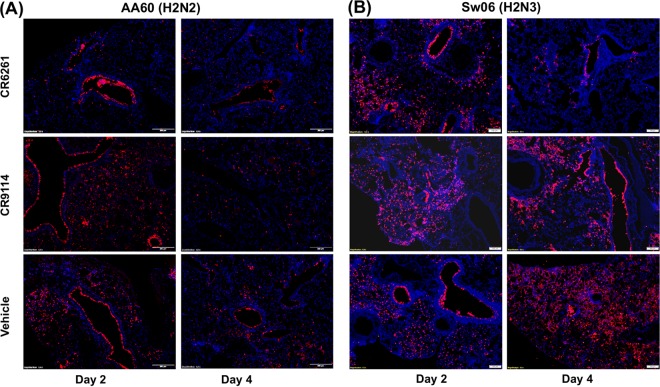

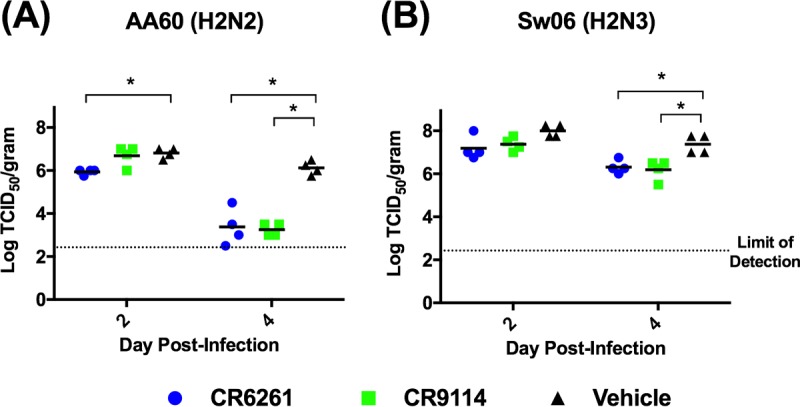

We next evaluated whether prophylaxis with CR6261 or CR9114 altered viral load, antigen distribution, and airway inflammation in the lungs. Mice were given 0 or 5 mg/kg of either bNAb i.p. and challenged 24 h later with AA60 or Sw06. As shown in Fig. 3A, on day 4 after AA60 challenge, prophylaxis with CR6261 or CR9114 significantly reduced pulmonary viral load by ∼100-fold, and on day 2 viral load was also significantly decreased in the CR6261 group. In the context of Sw06 challenge (Fig. 3B), neither bNAb reduced viral load on day 2. On day 4, both bNAbs significantly reduced viral titers; however, this reduction in titer was less than that observed in the AA60 challenge. To examine antigen distribution in the lungs, we performed immunohistochemical staining for viral HA protein. As shown in Fig. 4, the vehicle-treated animals challenged with AA60 or Sw06 had antigen staining in the airways and in the alveolar interstitium on both days 2 and 4. For AA60 challenge (Fig. 4A), prophylaxis with CR6261 altered antigen distribution, with viral antigen staining limited to the airways on both days, while CR9114 treatment did not alter antigen distribution. After Sw06 challenge (Fig. 4B), mice given CR6261 had antigen distribution similar to that of the vehicle-treated animals on day 2, but on day 4 viral antigen was largely limited to airways. For prophylaxis with CR9114, on day 2 antigen distribution was similar to that of vehicle-treated animals, while on day 4 antigen staining was more focally diffuse and often found in regions closer to the airways.

FIG 3.

Pulmonary viral load following CR6261 and CR9114 prophylaxis and H2 influenza virus challenge in mice. (A and B) BALB/c mice (n = 4 per time point) were given CR6261 or CR9114 (5 mg/kg) and then challenged 24 h later with 25 MLD50 of either A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 (H2N2) (A) or A/swine/MO/42964624/2006 (H2N3) (B). A vehicle (0 mg/kg) control was also included and challenged. On days 2 and 4 p.i., lung tissue homogenates were prepared and titrated on MDCK cells. Black bars indicate mean titers, while symbols represent titers for individual animals. An asterisk denotes significant difference from the vehicle control (P < 0.05).

FIG 4.

Pulmonary viral antigen staining following CR6261 and CR9114 prophylaxis and H2 influenza virus challenge in mice. Shown are representative immunohistochemical images of viral antigen staining of lung sections from days 2 and 4 postinfection in mice treated with 5 mg/kg of CR6261 or CR9114 and challenged with AA60 (A) or Sw06 (B). Images in the top and middle rows are from CR6261- and CR9114-treated mice, respectively, and those in the lower row are from vehicle-treated mice. Images were taken at ×10 magnification.

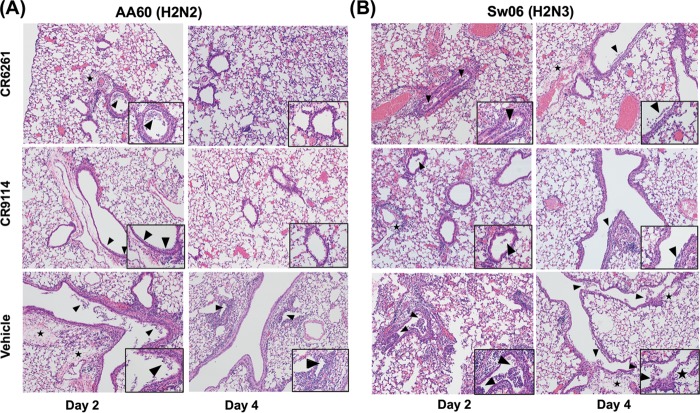

To evaluate the effect of antibody prophylaxis on airway inflammation, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained lung sections from bNAb- and vehicle-treated mice were compared. As shown in Fig. 5, all infected animals developed necrotizing bronchiolitis with some degree of perivascular edema; however, prophylaxis with CR6261 or CR9114 reduced the severity of disease. Following AA60 challenge (Fig. 5A), both antibodies reduced the degree of bronchiolar epithelial cell damage and necrosis on both days 2 and 4 and also reduced the extent of perivascular edema and inflammation. In the Sw06-challenged animals (Fig. 5B), the effect of antibody prophylaxis was less pronounced on day 2; only CR9114-treated animals showed reduced epithelial cell damage and necrosis and reduced perivascular inflammation relative to vehicle-treated mice. On day 4, both CR6261 and CR9114 similarly reduced the extent of edema and the amount of necrotic luminal debris (insets). Taken together, these findings indicate that both antibodies enhanced viral clearance and reduced airway inflammation and damage, and this was associated with recovery from weight loss and increased survival.

FIG 5.

Airway inflammation following CR6261 and CR9114 prophylaxis and H2 influenza virus challenge in mice. Shown are representative images of H&E-stained lung sections from days 2 and 4 postinfection in mice treated with 5 mg/kg of CR6261 or CR9114 and challenged with AA60 (A) or Sw06 (B). Images in top and middle rows are from CR6261- and CR9114-treated mice, respectively, and those in the lower row are from vehicle-treated mice. Images were taken at ×10 magnification, with inset images taken at ×40 showing the amount of necrotic debris. Arrows denote necrotic cellular debris or perivascular cuffing (inflammation), and a star denotes perivascular edema.

In vivo efficacy of CR9114 against AA60 is mediated by Fcγ receptor-dependent mechanisms.

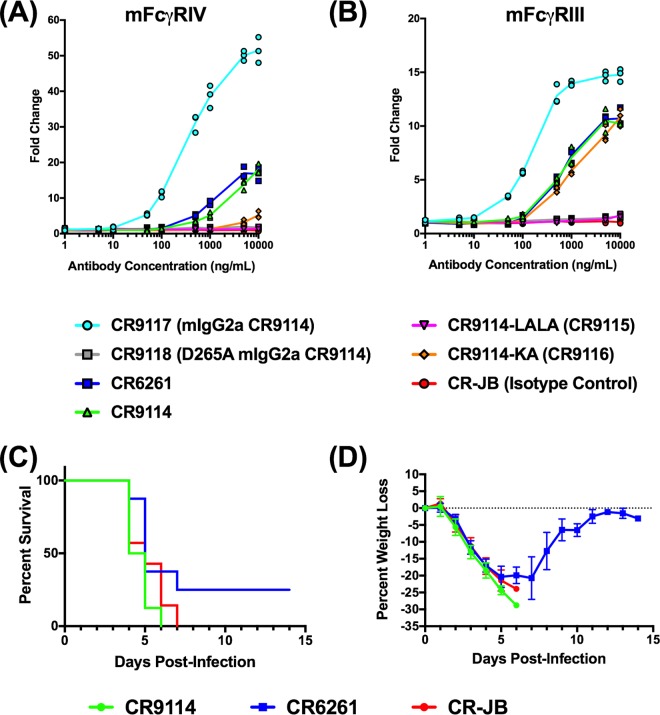

To further explore the mechanism of in vivo protection in the absence of in vitro neutralization of AA60 by CR9114, we performed studies with engineered variants of CR9114. Specifically, we evaluated CR9114 K322A (designated CR9114-KA or CR9116) and CR9114 L234A and L235A (CR9114-LALA or CR9115) (12, 18). Importantly, the KA mutation has been shown to reduce complement binding, while the LALA mutations reduce complement binding and Fcγ receptor (FcγR) binding in human and monkey cells (18). To verify that these antibodies lacked the ability to neutralize AA60 in vitro, we initially performed microneutralization assays against both AA60 and Sw06 (Table 1). As with CR9114, both CR9114-KA and CR9114-LALA were able to neutralize Sw06 but did not neutralize AA60. To examine the potential in vivo mechanism of CR9114, BALB/c mice were given CR9114, CR9114-KA, and CR9114-LALA i.p. at a dose of 1.7 mg/kg and challenged 24 h later with 25 MLD50 of AA60. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, all antibody-treated mice survived challenge, while less than 40% of vehicle-treated animals survived. However, weight loss in the CR9114- and CR9114-KA-treated groups was minimal, while the CR9114-LALA-treated mice showed greater and prolonged weight loss of 12 to 15%, with recovery starting on day 8. These findings suggest that FcγR-dependent mechanisms contributed to the in vivo efficacy of CR9114 against AA60 challenge.

FIG 6.

Efficacy of engineered variants of CR9114 in BALB/c mice and CR9114 in DBA mice against AA60 challenge. (A and B) BALB/c mice (n = 8 to 10) were administered CR9114, CR9114-KA, or CR9114-LALA i.p. at a dose of 1.7 mg/kg and challenged 24 h later with 25 MLD50 of AA60. Shown are percent survival (A) and percent weight loss (B) (mean ± SEM), with the proportion of animals that survived challenge indicated in brackets. A dagger represents a vehicle-treated mouse that succumbed to infection or that reached endpoint. (C and D) DBA mice were administered CR6261, CR9114, CR-JB (isotype control), or vehicle (antibody dilution buffer) and challenged 24 h later with 25 MLD50 of AA60. Shown are percent survival (C) and percent weight loss (D) (mean ± SEM).

As both CR9114-KA and CR9114-LALA reduce complement binding, we sought to verify that complement did not contribute to protection in vivo. Thus, we performed prophylaxis studies in complement-deficient DBA mice, which are highly sensitive to influenza challenge due to a deficiency in complement (C′5) of the complement pathway (19, 20). DBA mice were treated with 1.7 mg/kg of CR9114, CR6261, or CR-JB (isotype control) or vehicle and challenged with 25 MLD50 of AA60. All DBA mice treated with CR-JB or vehicle rapidly lost weight and succumbed to infection (Fig. 6C and D) with the exception of a single vehicle-treated mouse that recovered, while all of the mice treated with CR9114 or CR6261 survived challenge and exhibited a transient weight loss. These findings demonstrate that the protection mediated by CR6261 and CR9114 was not dependent on the complement pathway.

We next explored the role of FcγR-dependent mechanisms in protection against AA60 challenge. To verify that CR6261 and CR9114, which are human IgG1 antibodies, could utilize murine FcγRs and that the LALA mutations reduced binding to murine FcγRs, we performed antibody-mediated cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) reporter bioassays. Initially we used a murine FcγRIV reporter cell line because the murine FcγRIV receptor is the ortholog of human FcγRIII. Human FcγRIII is expressed on natural killer cells, and these cells mediate the classical ADCC pathway. In these assays, we compared the LALA and KA variants of CR9114, also designated CR9115 and CR9116, respectively, to CR9114, CR6261, CR9117 (mouse IgG2a variant of CR9114, included because mouse IgG2a is the ortholog of human IgG1), CR9118 (mouse IgG2a variant of CR9114 with D265A that abrogates Fc receptor binding), and CR-JB (human IgG1 isotype control). As shown in Fig. 7A, CR9117 induced the highest level of mFcγRIV activation, consistent with the high affinity of mouse IgG2a for this FcγR, while CR9118 induced minimal activation. CR9114 and CR6261 exhibited intermediate and comparable activation that was substantially reduced relative to that of CR9117. CR9114-KA was also capable of activating mFcγRIV, although the level of activation was low, with only a 5-fold increase above background at the highest antibody concentration. CR9114-LALA did not induce expression of the reporter gene above background, indicating that it was not able to activate or bind mouse FcγRIV.

FIG 7.

Evaluation of engineered variants of CR9114 in ADCC reporter assays and bNAb in Fcer1g−/− mice against AA60 challenge. (A and B) ADCC reporter assays for mouse FcγRIV (A) and FcγRIII (B). CR6261, CR9114, and several engineered variants, including CR9114-LALA (CR9115), CR9114-KA (CR9116), CR9117 (mouse IgG2a CR9114), CR9118 (mouse IgG2a CR9114 with the mutation D265A, which abrogates Fc receptor binding), and CR-JB (human IgG1 isotype control), were evaluated in the assays. ADCC assays were performed twice in triplicate, and the results of a representative assay are displayed. To further evaluate the role of FcγR in vivo, Fcer1g−/− mice were administered 1.7 mg/kg of CR9114, CR6261, or CR-JB and challenged 24 h later with 25 MLD50 of AA60. Shown are percent survival (C) and percent weight loss (D) (n = 8/group) (mean ± SEM).

As these findings, particularly with CR9114-KA, did not explain the discrepancies in weight loss between AA60-challenged CR9114-KA- and CR9114-LALA-treated mice (Fig. 6A and B), we next evaluated the same panel of antibodies in a murine FcγRIII reporter assay. In mice, FcγRIII is the only FcγR expressed on NK cells, and it is also expressed on polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes, which are capable of mediating ADCC (21). The overall magnitude of activation was lower for mFcγRIII than mFcγRIV (Fig. 7B; note the scale). There was a maximal change of 15-fold with CR9117, while levels for CR9114 and CR6261 were 10- to 12-fold above background. CR9116 (CR9114-KA) had activation comparable to that of CR9114, while CR9115 (CR9114-LALA) did not induce expression of the reporter gene above background. Because these findings were consistent with the in vivo prophylaxis data, we proceeded to evaluate CR9114 and CR6261 in Fcer1g−/− mice. Mice express four Fcγ receptors, named FcγRI to FcγRIV. Importantly, Fcer1g−/− mice lack FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV, but they express the inhibitory receptor FcγRII (22, 23). We treated Fcer1g−/− mice with 1.7 mg/ml of CR9114, CR6261, or CR-JB (isotype control) and challenged them with 25 MLD50 of AA60. Following virus challenge, all of the CR9114- and isotype control-treated mice rapidly lost weight and succumbed to infection by day 7 (Fig. 7C and D). All of the CR6261-treated mice lost weight rapidly; however, 2 of 8 animals recovered from weight loss and survived. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the in vivo protection conferred by CR9114 and CR6261 against AA60 challenge was mediated by FcγR interactions.

DISCUSSION

Broadly neutralizing Abs against influenza will be most useful if they are effective against viruses of all subtypes with pandemic potential. H2 viruses pose a pandemic threat because they have previously initiated a pandemic and continue to circulate in wild birds. Therefore, we investigated the efficacy of the HA stem bNAbs CR6261 and CR9114 against representative human and animal H2 influenza viruses. In vitro, CR6261 was able to neutralize both AA60, a human H2 virus, and Sw06, an animal H2 virus, while CR9114 displayed neutralizing activity only against Sw06. In contrast, at all doses tested (1.7 to 15 mg/kg) in vivo, both antibodies reduced weight loss and provided protection against mortality after AA60 and Sw06 challenge. With increasing doses of antibody, there was a corresponding decrease in weight loss. With 5 mg/kg of CR6261 or CR9114, there was a significant decrease in pulmonary viral load on day 4 postinfection and reduced airway inflammation, indicative of enhanced viral clearance.

Our findings are consistent with studies evaluating CR6261 and CR9114 against other influenza subtypes, where doses of 5 mg/kg or higher conferred protection against lethal challenge (13, 15). In agreement with studies on CR6261 prophylaxis followed by H5N1 challenge (14), we also observed a decrease in the extent of airway inflammation. Furthermore, as indicated by viral antigen staining, prophylaxis with CR6261 also limited the spread of the H2 viruses from the airways into the lung parenchyma consistent with studies on neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (24). As the greatest utility of bNAbs during a pandemic would be the ability to administer effective therapy or prophylaxis without specific knowledge of the viral subtype, our results show that CR6261 and CR9114 would be effective against H2 viruses in addition to other influenza subtypes.

Our findings further emphasize the importance of in vivo efficacy testing of bNAbs, because in vitro studies suggested that CR6261 and CR9114 had reduced neutralizing activity against H2 influenza viruses. As other components of the immune system may mediate protection, we used a strategy analogous to that of previous studies (12) and evaluated engineered mutants of CR9114 to gain insight into the mechanism of protection in vivo. Specifically, we compared the efficacy of CR9114 to those of CR9114-KA (CR9116) and CR9114-LALA (CR9115), which encode mutations previously shown to reduce complement binding and both complement and FcγR binding (12), respectively, in human and primate cells. Following AA60 challenge, we found that CR9114- and CR9114-KA-treated mice exhibited similar weight loss, while CR9114-LALA-treated mice showed substantially greater and prolonged weight loss (Fig. 6A and B). We further verified that activation of the complement pathway did not contribute to in vivo protection by showing that CR9114 and CR6261 were able to protect complement (C′5)-deficient DBA mice against AA60 and Sw06 challenge.

As CR9114 is a human IgG1 antibody, we next demonstrated CR9114 could utilize mouse FcγRs and that the LALA mutations abrogated binding by performing ADCC reporter assays using mouse FcγRIV- and FcγRIII-expressing cell lines. Human IgG1 was previously shown to bind to all four classes (i.e., FcγRI to FcγRIIV) of mouse FcγRs (21), and comparison of the level of activation of CR9118 (mIgG2a CR9114) to CR9114 in the FcγRIV and FcγRIII assays (Fig. 7A and B) shows that the magnitude of the response induced by CR9118 was ∼2- to 4-fold greater than that for CR9114. This is consistent with previous studies comparing matched human IgG1 and mouse IgG2a variants of a human monoclonal antibody targeting epidermal growth factor (21). Furthermore, comparison of the level of activation induced by CR9118 showed that this antibody induced 3- to 4-fold higher levels of FcγRIV activation relative to FcγRIII (Fig. 7A and B). In both assays, CR9114 and CR6261 also induced activation of the FcγRs at ∼20- and 10-fold changes above background levels for FcγRIV and FcγRIII, respectively. However, there were more pronounced differences in the level of activation of FcγRIV and FcγRIII by CR9114-KA and CR9114-LALA. CR9114-LALA failed to induce FcγR activation of both receptors, indicating that the LALA mutations abrogated FcγR binding. In contrast, CR9114-KA induced minimal activation of FcγRIV, but its activation of FcγRIII was equivalent to that of CR9114, indicating that the protective efficacy of CR9114-KA is mediated by FcγRIII binding.

Importantly, as FcγR-induced antibody-mediated cell cytotoxicity (ADCC) and antibody-mediated cell phagocytosis (ADCP) are effector mechanisms of bNAbs (22, 23, 25, 26) and our experiments with CR9114-LALA suggested that reduced FcγR binding resulted in enhanced morbidity, we performed additional studies in Fcer1g−/− mice, which lack FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV. CR9114 prophylaxis did not reduce mortality or weight loss in these mice, demonstrating that activating FcγR interactions is critical for protection (Fig. 7C and D). Furthermore, when CR6261, which exhibits in vitro neutralizing activity, was evaluated in parallel, mice exhibited substantial mortality and weight loss, indicating that the same mechanisms contribute to the efficacy of this antibody. These findings are consistent with the lack of protection of the bNAb FI6 in Fcer1g−/− mice challenged with H1N1 (i.e., PR8) virus (23) and with a more recent report showing that both neutralizing and nonneutralizing HA antibodies require FcγR interactions to mediate protection against challenge with the pandemic H1N1 virus in mice (26).

In summary, both CR6261 and CR9114 were able to prevent mortality from lethal H2 influenza virus challenge despite the observation that CR9114 showed reduced in vitro neutralizing activity relative to CR6261 against a human-origin H2 virus. CR9114 conferred in vivo protection that was mediated by FcγR-dependent mechanisms. Our findings demonstrate the importance of in vivo studies to demonstrate the efficacy of HA stem-binding antibodies. In the event of an H2 outbreak caused by previously circulating human H2N2 viruses or currently circulating animal influenza viruses, the administration of these antibodies could be a promising adjunct to antiviral therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

A/swine/MO/4296424/2006 (H2N3) was provided by Adolfo García-Sastre, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, and Juergen Richt, ARS-USDA, Ames, IA. A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 (H2N2) is a recombinant wild-type virus provided by MedImmune, Gaithersburg, MD. Both viruses were propagated in 9- to 11-day-old embryonated hen's eggs and were titrated on Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Virus titers were expressed as median tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50).

Monoclonal antibodies and neutralization assays.

The bNAbs CR6261, CR9114, CR9114-KA (CR9116), CR9114-LALA (CR9115), CR9117 (mouse IgG2a variant of CR9114), CR9118 (mouse IgG2a variant of CR9114 with D265A), and CR-JB (human IgG1 isotype control) were provided by the Crucell Vaccine Institute, Leiden, The Netherlands. Antibodies were diluted in vehicle buffer (20 mM sodium acetate, 75 mM NaCl, 5% sucrose, 0.01% Tween 80, pH 5.5) for administration to mice. Microneutralization assays were performed using dilutions of bNAbs (initial concentration, 10 mg/ml) as previously described against both AA60 and Sw06 (9). Briefly, 2-fold serial dilutions (starting concentration of 10 mg/ml) of each antibody were incubated with 100 TCID50 of AA60 or Sw06 virus for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the antibody-virus mixture was overlaid on MDCK cells in quadruplicate and incubated for 4 days at 37°C. At this time, cytopathic effect (CPE) was scored and neutralizing antibody titers were defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum that completely neutralized infectivity, as indicated by the absence of viral CPE.

Mouse prophylaxis studies.

For prophylaxis studies, 6-week-old female BALB/c, DBA/2, and Fcer1g−/− BALB/c mice were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). Mice were given bNAbs via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection at doses between 0 (vehicle buffer) and 15 mg/kg depending on experimental design. Twenty-four hours later, mice were anesthetized with 3% inhalational isoflurane and inoculated intranasally (i.n.) with 25 median mouse lethal doses (MLD50) of either AA60 or Sw06. For studies with KA and LALA variants of CR9114 or utilizing DBA and Fcer1g−/− mice, bNAbs were administered at a dose of 1.7 mg/kg and mice were similarly challenged 24 h later with AA60. Animals were weighed daily, and mice showing weight loss of 25% or greater were euthanized. To assess the effects on viral replication and pulmonary inflammation, BALB/c mice were given 5 mg/kg of either CR9114 or CR6261 i.p. and challenged 24 h later with AA60 or Sw06 i.n. On days 2 and 4 postinfection, lung tissues were collected; the left lung lobe was flash frozen for viral titration, and the right lobe was inflated and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. All experiments were conducted in biosafety level 3 enhanced laboratories at the National Institutes of Health, and all animal studies were approved by the NIH Animal Care and Use Committee.

Pathology and immunohistochemistry.

Formalin-fixed lung samples were embedded in paraffin, serially sectioned at 5-μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemistry, slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and then steamed in a DIVA Decloaker RTU (Biocare) for antigen retrieval. After a protein blocking step, slides were incubated with rabbit anti-influenza A virus nucleoprotein (GeneTex) at 1:200 dilution for 1 h at room temperature in a humidifying chamber. Detection was carried out with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories) and streptavidin conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (Life Technologies). Slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Subsequently, for all analyses lung sections were reviewed by a veterinary pathologist.

mFcγRIII and mFcγRIV ADCC reporter bioassays.

ADCC reporter assay kits were provided by Promega (Madison, WI) and were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, with modifications for use with adherent cells. A549 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in 10% FBS–RPMI medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in T75 flasks to a density of 90 to 100%. Subsequently, the cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 with AA60 A/Ann Arbor/6/1960 (H2N2) in Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with l-(tosylamido-2-phenyl) ethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (1 mg/ml) (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ). Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C and then detached from the flask with TrypLE (Invitrogen). The cells were resuspended in 10% FBS-RPMI, washed twice, and counted using a hemacytometer. Infected cells were seeded in opaque 96-well plates at a density of 25,000 cells per well in ADCC assay buffer and incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 1/2-log dilutions of antibodies, starting at a concentration of 104 ng/ml. Murine FcγRIII or FcγRIV ADCC effector cells were rapidly thawed and diluted in ADCC assay buffer, and 75,000 cells per well were added to the influenza virus-infected cells and incubated for 6 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The effector cells contain a luciferase gene under the control of an NFAT-response element (NFAT-RE). During the incubation, binding of antibodies to influenza antigens on the target cells and binding of the Fc region of the antibody to FcγR on the effector cells leads to expression of NFAT. NFAT then binds to the NFAT-RE, which induces expression of luciferase. After incubation, the cells were equilibrated to ambient temperature and incubated with Bio-Glo reagent for 8 min. Luminescence was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader (SpectraMax i3 multimode plate reader; Molecular Devices), and the results were expressed as fold change above background (0 ng/ml antibody control).

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v6 (La Jolla, California), with a P value of <0.05 considered significant. Lung titers were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U-test comparing titers of bNAb-treated mice to vehicle control-treated animals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH and NIAID.

W.K., R.M., J.G., and G.J. are employees of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Schonberger LB, Arden NH, Cox NJ, Fukuda K. 1998. Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution. J Infect Dis 178:53–60. doi: 10.1086/515616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joseph U, Linster M, Suzuki Y, Krauss S, Halpin RA, Vijaykrishna D, Fabrizio TP, Bestebroer TM, Maurer-Stroh S, Webby RJ, Wentworth DE, Fouchier RA, Bahl J, Smith GJ, CEIRS H2N2 Working Group . 2015. Adaptation of pandemic H2N2 influenza A viruses in humans. J Virol 89:2442–2447. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02590-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li XD, Zou SM, Zhang Y, Bai T, Gao RB, Zhang X, Wu J, Shu YL. 2014. A novel reassortant H2N3 influenza virus isolated from China. Biomed Environ Sci 27:240–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma MJ, Yang XX, Qian YH, Zhao SY, Hua S, Wang TC, Chen SH, Ma GY, Sang XY, Liu LN, Wu AP, Jiang TJ, Gao YW, Gray GC, Zhao T, Ling X, Wang JL, Lu B, Qian J, Cao WC. 2014. Characterization of a novel reassortant influenza A virus (H2N2) from a domestic duck in Eastern China. Sci Rep 4:7588. doi: 10.1038/srep07588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasick J, Pedersen J, Hernandez MS. 2012. Avian influenza in North America, 2009-2011. Avian Dis 56:845–848. doi: 10.1637/10206-041512-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng X, Wu H, Jin C, Yao H, Lu X, Cheng L, Wu N. 2014. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of H2N7 avian influenza viruses isolated from domestic ducks in Zhejiang Province, Eastern China, 2013. Virus Genes 48:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma W, Vincent AL, Gramer MR, Brockwell CB, Lager KM, Janke BH, Gauger PC, Patnayak DP, Webby RJ, Richt JA. 2007. Identification of H2N3 influenza A viruses from swine in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:20949–20954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710286104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Cheng X, Torres-Velez F, Orandle M, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2014. Evaluation of three live attenuated H2 pandemic influenza vaccine candidates in mice and ferrets. J Virol 88:2867–2876. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01829-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen GL, Lamirande EW, Yang CF, Jin H, Kemble G, Subbarao K. 2010. Evaluation of replication and cross-reactive antibody responses of H2 subtype influenza viruses in mice and ferrets. J Virol 84:7695–7702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00511-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones JC, Baranovich T, Marathe BM, Danner AF, Seiler JP, Franks J, Govorkova EA, Krauss S, Webster RG. 2014. Risk assessment of H2N2 influenza viruses from the avian reservoir. J Virol 88:1175–1188. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02526-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pappas C, Yang H, Carney PJ, Pearce MB, Katz JM, Stevens J, Tumpey TM. 2015. Assessment of transmission, pathogenesis and adaptation of H2 subtype influenza viruses in ferrets. Virology 477:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corti D, Suguitan AL Jr, Pinna D, Silacci C, Fernandez-Rodriguez BM, Vanzetta F, Santos C, Luke CJ, Torres-Velez FJ, Temperton NJ, Weiss RA, Sallusto F, Subbarao K, Lanzavecchia A. 2010. Heterosubtypic neutralizing antibodies are produced by individuals immunized with a seasonal influenza vaccine. J Clin Investig 120:1663–1673. doi: 10.1172/JCI41902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreyfus C, Laursen NS, Kwaks T, Zuijdgeest D, Khayat R, Ekiert DC, Lee JH, Metlagel Z, Bujny MV, Jongeneelen M, van der Vlugt R, Lamrani M, Korse HJ, Geelen E, Sahin O, Sieuwerts M, Brakenhoff JP, Vogels R, Li OT, Poon LL, Peiris M, Koudstaal W, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Goudsmit J, Friesen RH. 2012. Highly conserved protective epitopes on influenza B viruses. Science 337:1343–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1222908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Throsby M, van den Brink E, Jongeneelen M, Poon LL, Alard P, Cornelissen L, Bakker A, Cox F, van Deventer E, Guan Y, Cinatl J, ter Meulen J, Lasters I, Carsetti R, Peiris M, de Kruif J, Goudsmit J. 2008. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLoS One 3:e3942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koudstaal W, Koldijk MH, Brakenhoff JP, Cornelissen LA, Weverling GJ, Friesen RH, Goudsmit J. 2009. Pre- and postexposure use of human monoclonal antibody against H5N1 and H1N1 influenza virus in mice: viable alternative to oseltamivir. J Infect Dis 200:1870–1873. doi: 10.1086/648378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friesen RH, Koudstaal W, Koldijk MH, Weverling GJ, Brakenhoff JP, Lenting PJ, Stittelaar KJ, Osterhaus AD, Kompier R, Goudsmit J. 2010. New class of monoclonal antibodies against severe influenza: prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy in ferrets. PLoS One 5:e9106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Elsliger MA, Friesen RH, Jongeneelen M, Throsby M, Goudsmit J, Wilson IA. 2009. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science 324:246–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1171491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hessell AJ, Hangartner L, Hunter M, Havenith CE, Beurskens FJ, Bakker JM, Lanigan CM, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Parren PW, Marx PA, Burton DR. 2007. Fc receptor but not complement binding is important in antibody protection against HIV. Nature 449:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature06106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boon AC, deBeauchamp J, Hollmann A, Luke J, Kotb M, Rowe S, Finkelstein D, Neale G, Lu L, Williams RW, Webby RJ. 2009. Host genetic variation affects resistance to infection with a highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza A virus in mice. J Virol 83:10417–10426. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00514-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nilsson UR, Muller-Eberhard HJ. 1967. Deficiency of the fifth component of complement in mice with an inherited complement defect. J Exp Med 125:1–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.125.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overdijk MB, Verploegen S, Ortiz Buijsse A, Vink T, Leusen JH, Bleeker WK, Parren PW. 2012. Crosstalk between human IgG isotypes and murine effector cells. J Immunol 189:3430–3438. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takai T, Li M, Sylvestre D, Clynes R, Ravetch JV. 1994. FcR gamma chain deletion results in pleiotrophic effector cell defects. Cell 76:519–529. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV. 2014. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcgammaR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 20:143–151. doi: 10.1038/nm.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons CP, Bernasconi NL, Suguitan AL, Mills K, Ward JM, Chau NV, Hien TT, Sallusto F, Ha Do Q, Farrar J, de Jong MD, Lanzavecchia A, Subbarao K. 2007. Prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of human monoclonal antibodies against H5N1 influenza. PLoS Med 4:e178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandenburg B, Koudstaal W, Goudsmit J, Klaren V, Tang C, Bujny MV, Korse HJ, Kwaks T, Otterstrom JJ, Juraszek J, van Oijen AM, Vogels R, Friesen RH. 2013. Mechanisms of hemagglutinin targeted influenza virus neutralization. PLoS One 8:e80034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DiLillo DJ, Palese P, Wilson PC, Ravetch JV. 2016. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J Clin Investig 126:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI84428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]