ABSTRACT

Potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd) is a circular, single-stranded, noncoding RNA plant pathogen that is a useful model for studying the processing of noncoding RNA in eukaryotes. Infective PSTVd circles are replicated via an asymmetric rolling circle mechanism to form linear multimeric RNAs. An endonuclease cleaves these into monomers, and a ligase seals these into mature circles. All eukaryotes may have such enzymes for processing noncoding RNA. As a test, we investigated the processing of three PSTVd RNA constructs in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Of these, only one form, a construct that adopts a previously described tetraloop-containing conformation (TL), produces circles. TL has 16 nucleotides of the 3′ end duplicated at the 5′ end and a 3′ end produced by self-cleavage of a delta ribozyme. The other two constructs, an exact monomer flanked by ribozymes and a trihelix-forming RNA with requisite 5′ and 3′ duplications, do not produce circles. The TL circles contain nonnative nucleotides resulting from the 3′ end created by the ribozyme and the 5′ end created from an endolytic cleavage by yeast at a site distinct from where potato enzymes cut these RNAs. RNAs from all three transcripts are cleaved in places not on path for circle formation, likely representing RNA decay. We propose that these constructs fold into distinct RNA structures that interact differently with host cell RNA metabolism enzymes, resulting in various susceptibilities to degradation versus processing. We conclude that PSTVd RNA is opportunistic and may use different processing pathways in different hosts.

IMPORTANCE In higher eukaryotes, the majority of transcribed RNAs do not encode proteins. These noncoding RNAs are responsible for mRNA regulation, control of the expression of regulatory microRNAs, sensing of changes in the environment by use of riboswitches (RNAs that change shape in response to environmental signals), catalysis, and more roles that are still being uncovered. Some of these functions may be remnants from the RNA world and, as such, would be part of the evolutionary past of all forms of modern life. Viroids are noncoding RNAs that can cause disease in plants. Since they encode no proteins, they depend on their own RNA and on host proteins for replication and pathogenicity. It is likely that viroids hijack critical host RNA pathways for processing the host's own noncoding RNA. These pathways are still unknown. Elucidating these pathways should reveal new biological functions of noncoding RNA.

KEYWORDS: RNA conformation, RNA processing, host functions, mRNA degradation, noncoding RNA, viroids

INTRODUCTION

Viroids are subviral, circular, single-stranded RNA replicons that infect many different species of plants. They are small (240 to 600 nucleotides [nt]), lack a protein coat, and are highly structured, and there is no evidence of any viroid translation product (1–4). Due to this lack of a translation product, viroid replication and pathogenesis depend on the RNA itself, host factors, and the host enzymatic machinery (5). Additionally, viroids have high rates of in vivo mutation compared to other nucleic acid-based pathogens (6, 7). These attributes make viroids enticing models for studying RNA structure-function relationships.

The 34 known viroid species are categorized into two families: Pospiviroidae and Avsunviroidae. Members of the Avsunviroidae family exist as minus- and plus-strand RNAs in infected tissue. They replicate via symmetric rolling circles in chloroplasts by using the nuclear encoded polymerase (NEP) (8, 9). Production of monomeric (mon) linear RNAs relies on self-cleavage by hammerhead ribozymes encoded in the plus- and minus-strand viroid RNAs. A host ligase is presumed to circularize the viroids (10–13).

The replication of viroids within the Pospiviroidae family differs from that of viroids of the Avsunviroidae family in several main aspects: (i) their plus strand dominates the cells; (ii) they are replicated through an asymmetric rolling circle mechanism in the nucleus, using host RNA polymerase II (Pol II); and (iii) they do not contain a ribozyme sequence for self-cleavage (14–18) and therefore rely on a host nuclease. Specifically, plus-strand circular RNAs enter the nucleus and are transcribed by Pol II into linear minus-strand multimeric RNAs, serving as templates for Pol II to create the plus-strand multimeric linear RNAs. The plus-strand multimers are then cleaved and ligated into plus-sense viroid circles (19–21).

Potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd), the representative viroid of the Pospiviroidae family, adopts an unbranched, highly base-paired, rod-like conformation (22) (Fig. 1) that has five domains: terminal left domain, pathogenicity-modulating domain, central conserved region (CCR), variable domain, and terminal right domain (23). The CCR is a region of high homology among members of the Pospiviroidae family, and it was found that linear RNA transcripts with short terminal duplications (8 to 11 nucleotides) in this region were highly infectious (24–29). Thermal denaturation studies indicated that the native secondary structure of PSTVd is disrupted upon exiting Pol II and that the CCR folds into a stable hairpin (HP1); this hairpin may be involved in the processing of oligomeric plus-sense PSTVd to mature circles (30). Diener (31) proposed that two HP1 motifs can align oligomers into a position for cleavage/ligation by forming a thermodynamically stable, highly base-paired structure termed the “trihelix” (triH) (Fig. 1C) (32–34). In addition, it was shown that PSTVd RNAs that contain CCR duplications can fold into a number of metastable conformations (35, 36).

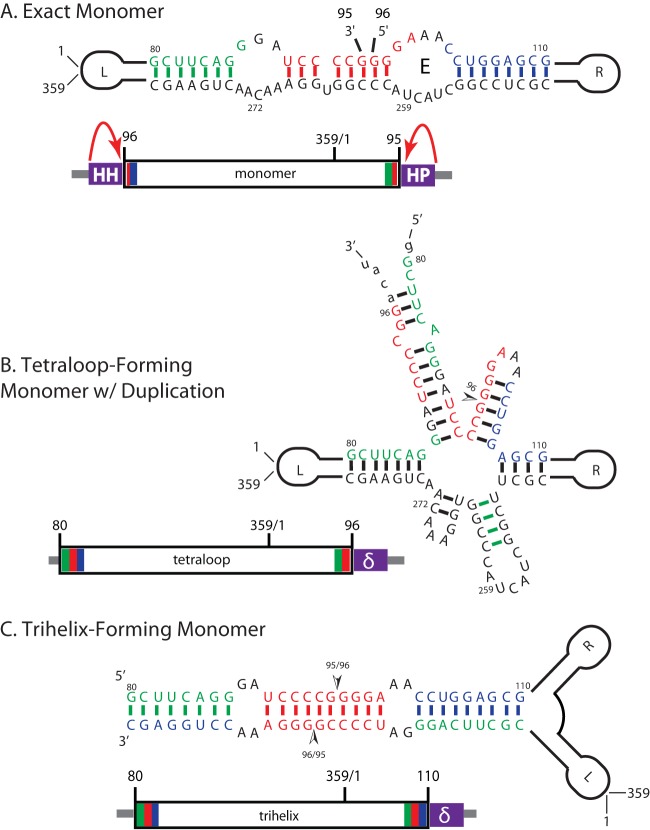

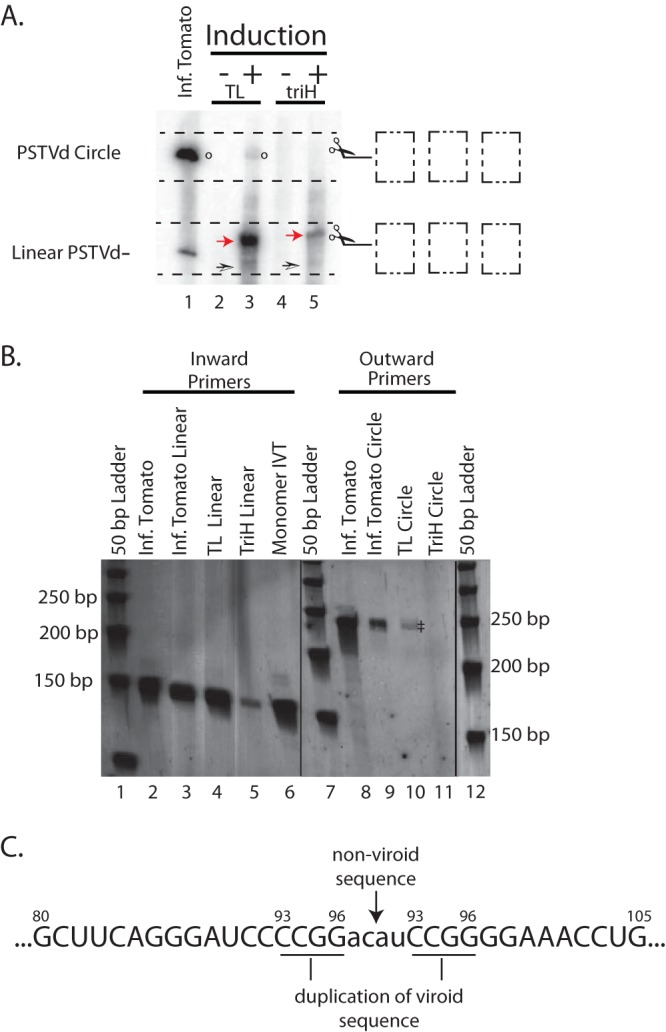

FIG 1.

In vivo constructs and corresponding structural motifs used to express PSTVd in yeast. The left and right arms of PSTVd are indicated schematically, while the nucleotides of the CCR upper and lower strands are given explicitly. Nucleotides shown in green (nt 80 to 87), red (nt 90 to 99), and blue (nt 102 to 110) are part of the upper CCR (UCCR), which is duplicated to a different extent in each construct. (A) Monomer construct. The construct is flanked by 5′ hammerhead (HH) and 3′ hairpin (HP) ribozymes, which cleave at the curved arrows. Upon ligation, the construct should fold into the wild-type extended rod containing a loop E motif. (B) GNRA tetraloop (TL) construct. 3′ duplication of UCCR nucleotides 80 to 96 (green) allows formation of a metastable structure in which nucleotides 93 to 106 form a stem capped by the tetraloop; this stem contains the position 95/96 processing cleavage site (arrowhead). This construct contains a 3′ delta ribozyme (δ). (C) Trihelix-forming monomeric (triH) construct. The triH RNA has the same 5′ end as the TL RNA; its 3′ end duplicates nucleotides 80 to 110 (green, red, and blue). The two complete copies of the UCCR hybridize to form the trihelix (top), which has two potential position 95/96 cleavage sites (arrowheads).

Multiple structural studies soon followed to elucidate the exact structural elements required for viroid processing. Using transcript processing in potato nuclear extracts, a PSTVd RNA containing a 17-nt duplication of the CCR was found that converts into wild-type circles. Processing required that this transcript adopt one specific fold of the four possible secondary structures. Access to each secondary structure was controlled by temperature, ionic strength, and structure-directing cRNA oligonucleotides. Interestingly, one structure had the trihelix, which encompasses the proposed cleavage site (Fig. 1C), but it was not processed into a mature viroid circle (36). The only structure to be cleaved and ligated was the “extended middle” structure. Additional work using UV cross-linking, chemical mapping, temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TGGE), and thermodynamic calculations showed that the CCR of the “extended middle” structure folds into a GNRA tetraloop (Fig. 1B). After cleavage, the tetraloop region switches into the extended rod conformation, containing a loop E motif that dictates ligation (37, 38).

In contrast to the tetraloop model, an in vivo study of transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana by Gas et al. suggested that cleavage is controlled by the trihelix structure (39). They proposed that kissing loop interactions by HP1 structures in sequential arrangement on a dimeric RNA or on different monomers initiate the formation of the trihelix. Specifically, they introduced mutations in the citrus exocortis viroid (CEVd; Pospiviroidae family) that are expected to abolish the formation of the GNRA tetraloop. These mutations had no adverse effect on cleavage. They also observed that not all members of the Pospiviroidae family are capable of forming GNRA tetraloop motifs within the CCR. All these factors led them to conclude that the trihelix is the substrate for cleavage in vivo in all members of the Pospiviroidae family (20). Both the trihelix and tetraloop models postulate that formation of a loop E motif promotes ligation in members of the Pospiviroid genus.

The structural debate is further complicated by results from additional experiments on members of the Pospiviroidae family whose CCR may adopt an alternate form of the tetraloop. Thus, multiple options exist by which the CCR rearranges to allow cleavage and ligation (40). Lastly, work using PSTVd-infected Nicotiana benthamiana showed that mutations that disrupt HP1, the sequence that forms the trihelix, have a strong effect on viroid trafficking but little effect on replication (41, 42).

To further understand the structural requirements for PSTVd processing, we used the nonconventional host Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model system, as this host has become a convenient molecular biological tool (43, 44) for studying RNA processing and replication in vivo. Specifically, yeast contains the cellular machinery to replicate several plus-strand RNA viruses (45, 46) and was recently shown to support replication of avocado sunblotch viroid (ASBVd; Avsunviroidae family) (47). Here we report that PSTVd RNAs under the control of a galactose-regulated expression vector can be processed effectively. This system allowed us to investigate the structural requirements for viroid cleavage and ligation in yeast. We created DNA constructs that produce three RNA transcripts of exactly or slightly larger than monomeric length designed to preferably adopt (i) an exact monomer with an unbranched rod-like structure, (ii) an extended CCR that forms a tetraloop-containing conformation (TL), and (iii) a complete duplication of the CCR upper strand (UCCR) that folds into the trihelix (triH). When these were tested for processing in vivo, the only construct that was cleaved and ligated into mature circular progeny was the TL-forming construct. Consistent with thermodynamic data, these subtle changes in the extent of duplication have strong effects on the processing of these RNAs. In this yeast system, only the tetraloop-containing construct is processed to circles; the other constructs fold into structures that are not efficiently recognized by the processing enzymes and instead are targeted for degradation. The evidence of PSTVd processing in a nonplant system is further testament to viroids utilizing fundamental RNA biology that all organisms share.

RESULTS

Proper cleavage of a longer-than-unit-length viroid RNA in plants depends upon the length and border sequence of the duplications around the monomer (36–39). Furthermore, efficient ligation requires compatibility of the ends generated by the RNA endonuclease and the ligase that joins them (48, 49), and a structural context that puts the ends in close proximity and paired with cRNA.

We created the following three PSTVd RNA constructs representing the major conformations recognized in previous studies: (i) an exact monomer (mon), which should ligate to form the mature rod-like RNA (Fig. 1A) even if yeast has no appropriate endonucleases; (ii) a monomer with duplications (tetraloop [TL]), containing a 3′ 17-nt duplication in the upper central conserved region (UCCR), which should fold into the metastable tetraloop (Fig. 1B); and (iii) a trihelix (triH) with the full 30-nt UCCR duplication (i.e., the TL 5′ end and 13 more nucleotides added to the 3′ end), which is the sequence required for adopting the complete trihelix structure (Fig. 1C). This construct differs from the “trihelix” used before, which lacked one of the helical segments (36).

Construction of PSTVd-yeast expression systems.

The PSTVd sequences were cloned into a yeast expression vector under the control of the GAL1 promoter and transformed into yeast strain YPH500 for growth and expression under galactose induction conditions. All three RNAs will be transcribed by RNA Pol II and are expected to be 5′ capped. The plasmid for transcription of the PSTVd monomer has a DNA cassette containing the 359 viroid nucleotides flanked by sequences for the hammerhead and hairpin ribozymes at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. The resulting PSTVd monomer starts at base 96 and continues via base 359/1 to base 95, the same as the RNA that is ligated into a circle in plants (Fig. 1A). The other two constructs (TL and triH) contain a single ribozyme, the delta ribozyme, 3′ to the viroid sequences. These two constructs have duplications at the 5′ (pre-nt 96) and 3′ (post-nt 95) ends, as described above and shown in Fig. 1. All ribozymes self-cleave to generate 5′-hydroxyl (monomer only) and 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate termini. We refer to RNAs that have had ribozymes cleaved but no other cleavage as primary transcripts.

RT-PCR indicates expression and PSTVd processing.

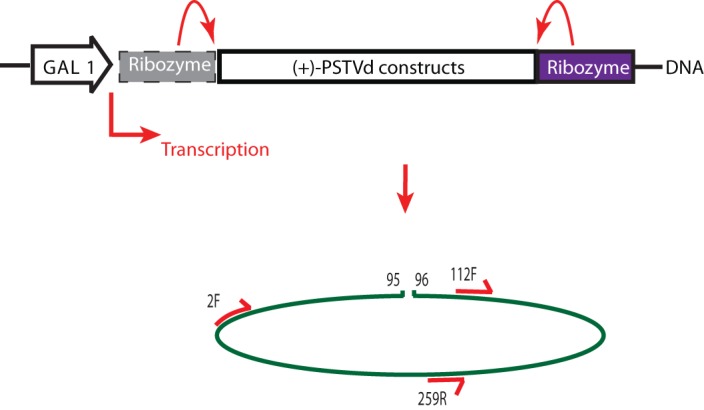

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was employed to confirm the expression of plus-strand viroid-specific RNA in total RNA preparations from cells and to detect the possible presence of PSTVd circles that would result from processing of linear precursors. This RT-PCR scheme is shown in Fig. 2. The inward primer set, 112F and 259R (see Fig. 1 for numbering), should always yield a PCR product of 148 bp, as long as there is plus-sense PSTVd RNA present with an intact right half. RNAs transcribed from all three constructs will be templates for synthesis of this fragment. The outward primer set, 2F and 259R, will yield an amplification product only when ligation unites the two halves of the UCCR. Thus, only circular RNA products will give rise to a 240-bp DNA fragment with the outward primers.

FIG 2.

Transcription of constructs in yeast and corresponding ligation-monitoring RT-PCR scheme. Once the PSTVd RNA is transformed into yeast, galactose induces its transcription. Upon induction and transcription, the RNA will fold into the structures seen in Fig. 1 for processing and ligation within the UCCR; the example shown here is the exact monomer transcript open at the 95/96 site. For analysis, the RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed, and then PCR amplified using primers 112F and 259R (inward) to screen for all plus-sense PSTVd or primers 2F and 259R (outward) across the UCCR region to screen specifically for processed circles. The gray box represents the hammerhead ribozyme, which undergoes self-cleavage in the monomer construct. All constructs contain a 3′ ribozyme; only the exact monomer construct contains the 5′ ribozyme.

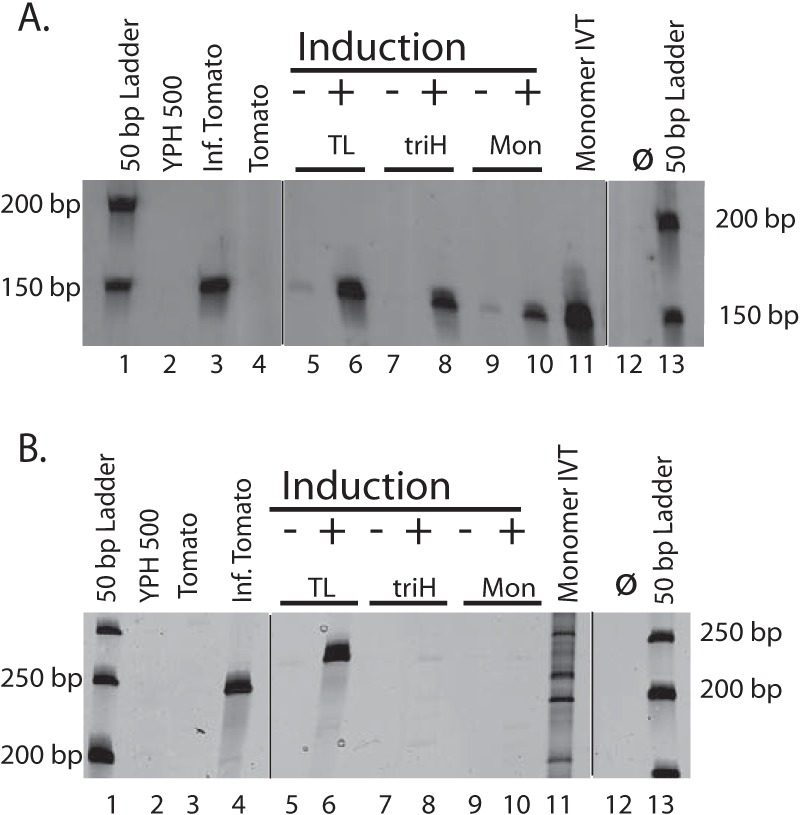

Figure 3 shows the results of RT-PCR detection of plus-sense PSTVd expression in yeast. Galactose induced transcription in YPH500 strains containing the TL (+), triH (+), and mon (+) constructs, as evidenced by the presence of the expected 148-bp product from the inward primer set (Fig. 3A, lanes 6, 8, and 10).

FIG 3.

Detection of plus-sense PSTVd and PSTVd circles in total RNA from induced yeast by use of RT-PCR. (A) RT-PCR with the inward primer set 112F/259R revealed that all PSTVd RNAs tested produced a 148-bp DNA fragment. Lanes: 2, empty yeast strain; 3, PSTVd-infected tomato; 4, healthy tomato; 5 to 10, RNAs from yeast strain YPH500 transformed with plasmids containing the PSTVd constructs listed in Fig. 1. The positive control was an in vitro transcript of a PSTVd monomer (lane 11), and lane 12 contains a transcript-free RT-PCR control. RNAs were extracted from yeast grown in galactose-containing induction medium (+) or noninducing dextrose medium (−). The molecular size markers are from a 50-bp DNA ladder. (B) RT-PCR with the outward primer set 2F/259R revealed the presence of circular PSTVd RNA as a 240-bp (tomato) or 248-bp (yeast) DNA duplex. The lane order is the same as in panel A, with the exception of the infected and healthy tomato samples. The different migration behaviors of the marker bands in lanes 1 and 13 are due to an electrophoretic “smile.” Black lines indicate deleted lanes; all lanes in one panel were run in the same gel.

Circle/multimer detection using the outward primer set gave rise to the expected 240-bp band for the infected tomato plant (Fig. 3B, lane 4). Of the three constructs, only TL (lane 6) yielded a similar band. This band migrated slightly more slowly, indicating a size slightly larger than 240 bp. Importantly, expression of the triH construct did not direct the formation of a 240-bp fragment in this assay (lane 8), even though the inward primer pair demonstrated strong expression of the precursor plus-strand triH RNA (Fig. 3A, lane 8).

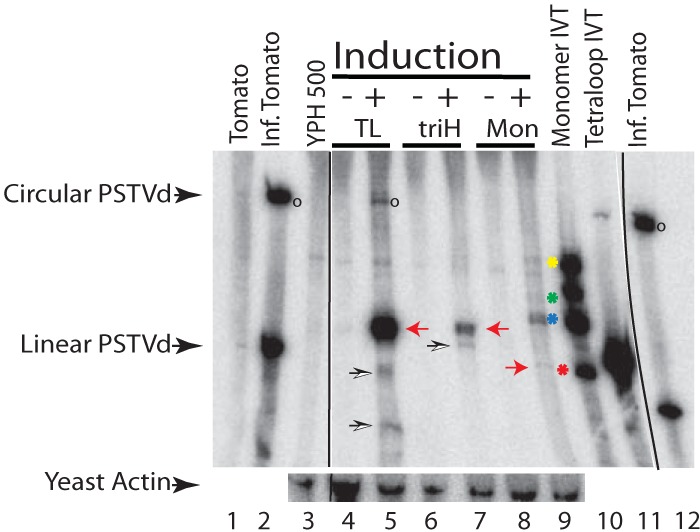

Northern blot detection of PSTVd primary transcripts, degradation products, and circles.

Expression of TL (+), triH (+), and mon (+) was confirmed by Northern blotting (Fig. 4). Total RNAs isolated from yeast cells containing the expression plasmids and grown under inducing (+) or noninducing (−) conditions were separated by electrophoresis, transferred to a membrane, and probed using a radiolabeled minus-sense full-length viroid RNA. As expected, PSTVd-derived RNA species for all three constructs could be detected only after induction (Fig. 4, lanes 5, 7, and 9). RNAs from PSTVd-infected tomato plants provided both linear and circular migration standards (lanes 1, 2, and 12). The monomer in vitro transcript (IVT) (lane 10) shows four bands. From top to bottom, these are the primary transcript with both ribozymes still attached (547 nt), two intermediate products in which either only the hairpin or only the hammerhead ribozyme has been cleaved (482 and 424 nt, respectively), and the proper monomer released by cleavage of both ribozymes (359 nt). The corresponding double-ribozyme in vivo construct yielded only a weak monomer band, indicating low-efficiency cleavage of the two ribozymes (lane 9). The most prominent RNA band in this lane results from cleavage by the hammerhead ribozyme but not the hairpin ribozyme cleavage. Both the TL and triH RNA in vivo constructs displayed an RNA band in the range of linear molecules slightly larger than the unit-length linear molecule (lanes 5 and 7, red arrowheads), in good agreement with the expected size with the UCCR duplication and matching the size of the in vitro transcript (lane 11). Multiple repeats of this Northern blot assay clearly and consistently displayed that the TL construct had the highest level of RNA accumulation in vivo of all constructs tested. For both the TL (+) and triH (+) conditions, there are signs of smaller RNAs below the primary transcripts. For example, the TL construct consistently yielded at least one shorter RNA species (lane 5, open arrowheads) that closely migrates with the exact linear monomeric RNA (lanes 2, 10, and 12). Numerous Northern blots indicate that this band is slightly smaller than an exact linear monomer.

FIG 4.

Northern blot analysis of total RNA from yeast expressing PSTVd. Total RNAs from healthy tomato (lane 1), infected tomato (lane 2), empty YPH500 (lane 3), and YPH500 transformed with the indicated constructs (lanes 4 to 9) were separated in a 5% PAA gel and blotted onto a positively charged nylon membrane. Induction conditions were provided by use of dextrose (−) and galactose (+) media. In vitro transcripts corresponding to the mon and TL constructs were used as positive controls (lanes 10 and 11). The ribozymes of the monomer IVT (lane 10) (see Fig. 1A) did not cleave to completion, resulting in four bands: HH-PSTVd-HP (547 nt; yellow asterisk), PSTVd-HP (482 nt; green asterisk), HH-PSTVd (424 nt; blue asterisk), and linear PSTVd (359 nt; red asterisk). The blot was probed with an α-32P-labeled minus-sense PSTVd transcript. Linear and circular PSTVd RNAs are marked. For a loading control, the yeast actin gene (1,537 nt) was probed in a second hybridization. Actin migrates above circular PSTVd. Red arrows for lanes 5 and 7 indicate primary transcripts from the in vivo transcripts prior to any yeast cleavage/ligation events (in vivo) for TL and triH. An open circle denotes circular products resulting from processing of the TL construct in vivo (lane 5). A red arrow for lane 9 marks the linear monomer-length band of the monomer. Black lines indicate deleted lanes; all lanes in one panel were run in the same gel.

Gel extraction of linear and circular PSTVd, followed by RT-PCR and sequence analysis.

In the previous experiments, Northern blots and RT-PCR amplifications were performed on separate RNA preparations. Figure 5 directly confirms that the circles observed in Northern blots were responsible for the 240-bp RT product amplified across the circle junction. Total RNAs from induced and uninduced cells containing plasmids with the TL or triH expression cassette were separated in a 5% polyacrylamide (PAA) denaturing gel in duplicate. One duplicate was subjected to Northern blotting using minus-sense PSTVd RNA as a probe (Fig. 5A). The other was stained with ethidium bromide, enabling gel regions corresponding to standard linear and circular RNA species from infected tomato to be cut out (Fig. 5A, dashed lines). RNAs extracted from these bands were used as the substrates for RT-PCR; each sample was tested with both inward- and outward-facing primer pairs.

FIG 5.

RT-PCR of gel-excised linear and circular PSTVd RNAs, Northern blot confirmation, and sequence data. A denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gel with duplication of five lanes was run and cut in half. (A) The left half was used for a Northern blot. Lane 1, positive control (infected tomato); lanes 2 and 3, yeast total RNA from the TL construct; lanes 4 and 5, yeast total RNA from the triH construct. Red arrows indicate primary transcripts, open arrows indicate cleavage products of viroid RNA, and circles designate circular PSTVd products. (B) Regions indicated by scissors and dashed boxes in panel A were excised from the right half of the gel, and the RNAs were extracted and used as templates for RT-PCR. For lanes 2 to 6, we used the inward primer set 112F/259R to reveal plus-sense PSTVd; for lanes 8 to 11, we used the outward primer set 2F/259R to reveal circular PSTVd RNA. Lanes 2, 6, and 8 are positive controls from RT-PCRs with RNAs that were not gel extracted; lanes 3 and 9 show gel-extracted linear/circular RNAs from infected tomato. The template RNAs for lanes 4 and 10 and lanes 5 and 11 were the extracted linear/circular bands from induced TL and triH RNAs, respectively, from the gel in panel A. Black lines indicate deleted lanes; all lanes in one panel were run in the same gel. (C) Sequence results for gel-extracted circles from TL in yeast. The lowercase letters represent a nonviroid vector sequence, and the bars indicate duplications of the viroid sequence.

The results are presented in Fig. 5A. As before, the Northern blot showed linear, longer-than-unit-length RNAs in both the induced TL and triH samples. A band comigrating with PSTVd circular RNA from infected tomato is seen only in the induced TL lane (Fig. 5A, lane 3), not in the induced triH lane (lane 5). RT-PCR analysis with the inward primer set gave rise to the 148-bp band from RNAs extracted from both the TL and triH RNA linear regions, as expected. Importantly, outward RT-PCR with RNAs extracted from the area of expected circular species resulted in a 240-bp-like product for the TL RNA (Fig. 5B, lane 10, double dagger) and positive controls only, not for the triH RNA (lane 11).

The DNA product obtained through RT-PCR and shown in Fig. 5B, lane 10, was sequenced using the primers for outward PCR to confirm circularization of the RNA template. Unexpectedly, this revealed that eight additional nucleotides had been inserted at the ligation junction, corresponding to a 4-nt duplication of the PSTVd sequence (nt 93 to 96) and four vector-derived nucleotides (ACAU) located directly upstream, 5′ of the delta ribozyme cleavage site (Fig. 5C). The same sequence was observed in three independent analyses of yeast circular RNAs. The sequence of events best able to explain this outcome is a yeast endonuclease-driven cleavage of the 5′ end, between nucleotides 92 and 93, and a 3′ cleavage at the expected location upstream of the delta ribozyme, followed by ligation of the two heterogeneous ends, as described in more detail in Discussion.

Based on this model, we would expect to find a linear, 367-nt RNA with nucleotide 93 at its 5′ end. Other, longer intermediates may be possible. The Northern blots (e.g., Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 7, and Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 5) show possible candidate bands (open arrowheads) for TL and triH constructs expressed in vivo. These putative intermediates do not appear on every blot. However, in every case where we have seen them and mapped their size, they were not consistent with an exact monomer, with or without the eight-base insert indicated by the circle sequence.

Mapping of 5′ cleavage sites by primer extension.

Primer extension is a more precise method for mapping 5′ ends of linear RNA molecules. Initial experiments could not even reproducibly detect the primary transcript in different total RNA preparations, prompting us to search for ways to enrich and possibly stabilize the transcript and its processing intermediates. Two different approaches were explored. For the first, Semancik and Szychowski (50) showed that PSTVd RNA can be enriched using 50 mM Mn2+. This precipitates single-stranded RNAs of >∼300 nt but does not precipitate PSTVd RNA. For the second, knocking down RNases in vivo might stabilize intermediates. RAT1 is an essential nuclear 5′-to-3′ exoribonuclease gene. Cells with a nonlethal allele, RAT1-107, display reduced RNA degradation (51). Levels of linear transcripts from our various PSTVd cassettes, as well as circles from the TL construct, were elevated in a strain with this allele (Fig. 6). With the combination of Mn2+ precipitation and the RAT1-107 mutation in YPH500, primary and putative processed RNAs were reproducibly observed in primer extension assays. Figure 7 presents an autoradiogram of a primer extension assay, with a major band at the −3 position when the TL construct was induced (lane 7, red arrow), indicating the transcription start within the GAL1 promoter. The triH construct should produce the same band, as its 5′ end is equivalent to that of the TL construct, yet this band was not detected despite the use of both RAT1-107 and Mn2+ precipitation (lane 5). This result is in agreement with the Northern blots, in which the TL construct always produced more primary transcript than that seen with the triH construct.

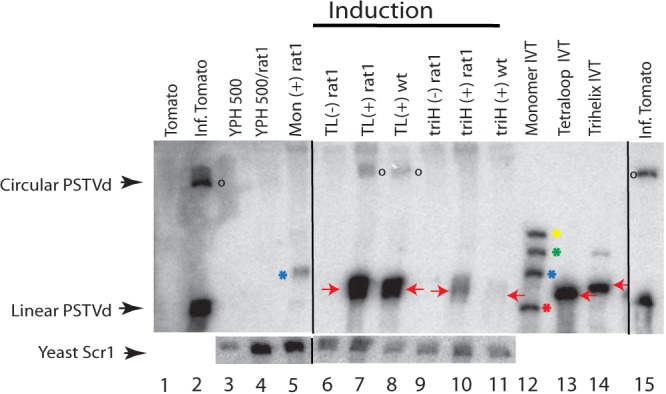

FIG 6.

Northern blot analysis of total RNAs from PSTVd-infected wild-type and RAT1 mutant YPH500 yeast strains. Total RNA controls included healthy tomato (lane 1), infected tomato (lane 2), empty YPH500 (lane 3), and the plasmid-free RAT1 strain (lane 4). Lane 5, galactose induction (+) of the RAT1 strain transformed with the monomer construct; lanes 6 and 7, RAT1 strain transformed with the TL construct under dextrose (−) and galactose (+) induction conditions; lanes 9 and 10, RAT1 strain transformed with the triH construct under dextrose (−) and galactose (+) induction conditions; lanes 8 and 11, YPH500 strain with galactose induction of the TL and triH transformants. In vitro transcripts corresponding to each in vivo construct were used as positive loading controls (lanes 12 to 14). The ribozymes of the monomer IVT (lane 12) (see Fig. 1A) did not cleave to completion, resulting in four bands: HH-PSTVd-HP (547 nt; yellow asterisk), PSTVd-HP (482 nt; green asterisk), HH-PSTVd (424 nt; blue asterisk), and linear PSTVd (359 nt; red asterisk). The blot was probed with an α-32P-labeled minus-sense PSTVd transcript. Linear and circular PSTVd RNAs are marked. For a loading control, the yeast Scr1 gene (522 nt) was probed in a second hybridization. Red arrows indicate primary transcripts from the in vitro transcripts or prior to any yeast cleavage/ligation events (in vivo), blue asterisks show HH-PSTVd RNA, and open circles denote circular products resulting from processing of the TL construct in vivo (lanes 7 and 8). Black lines indicate deleted lanes; all lanes were run in the same gel.

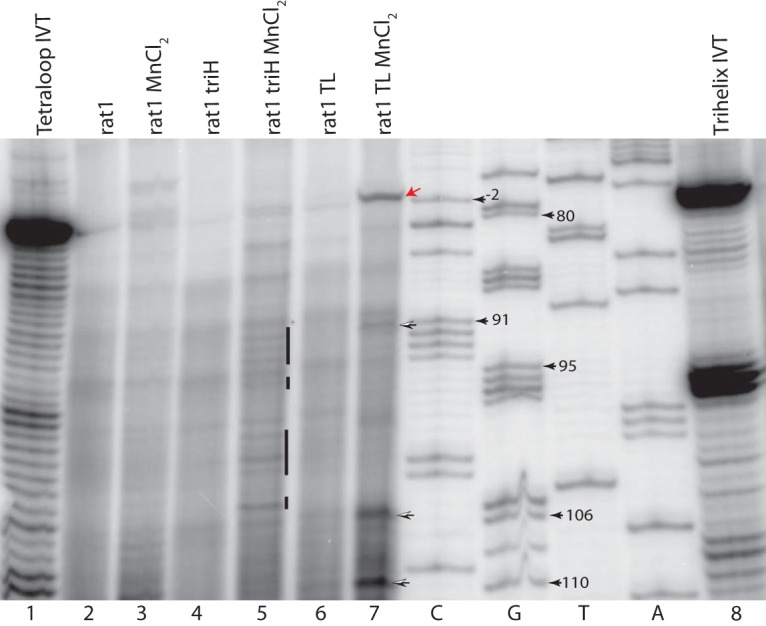

FIG 7.

Determination of RNA 5′ ends for viroid species detectable in vivo. Total RNA was prepared from a yeast RAT1-107 mutant expressing the PSTVd TL and triH constructs. Untreated (25 μg) and MnCl2-treated (12.5 μg) RNAs were then analyzed by primer extension. In vitro transcripts (0.5 pmol) of TL and triH (lanes 1 and 8) were used as controls. The 5′ ends of both in vitro transcripts are identical, and transcription starts at position G80. Lanes 2 and 3, RNAs from plasmid-free RAT1-107 mutant, without and with MnCl2 treatment; lanes 4 and 5, RNAs from triH-transformed RAT1-107 mutant, without and with MnCl2 treatment; lanes 6 and 7, RNAs from TL-transformed RAT1-107 mutant, without and with MnCl2 treatment. Position −2C (red arrow) marks the yeast transcription start site in constructs harboring a GAL1 promoter. Position G80 marks the first PSTVd base. Open arrows indicate additional 5′ ends/degradation products detectable in the MnCl2-enriched TL RNA (lane 7). The bars in lane 5 indicate the high level of additional 5′ ends/degradation products seen in the triH variant compared to those in the TL variant.

The TL primary transcript lane does show processing of the primary transcript, with major bands at positions 110 and 106 and a minor band at position 91. None of these is consistent with the circle sequence, which indicates cleavage at position 92/93, or with the cleavage at position 95/96 seen in plants (38, 39). If the 3′ ends of the RNAs with cleavage after position 106 or 110 were the expected cleavage site of the delta ribozyme, these bands would be consistent with the nearly monomer-sized bands that appeared with TL and triH primary constructs (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 7). Possible processed bands are also seen for the Mn2+-precipitated RNAs from the trihelix construct. These are lighter, more numerous, and at positions distinct from those seen for the TL RNA (Fig. 7, lane 5, vertical bars). These lanes should be compared to the control lane (lane 3) with YPH500 RAT1-107 strain Mn2+-precipitated RNA without plasmid. All of these shorter-than-primary-transcript bands may have arisen from multiple 5′ ends created during the degradation or other processing of the triH transcript. This indicates that all of our primary transcripts face degradation in yeast and that any change in sequence, whether full duplication or the addition of just a few bases, changes the degradation pattern significantly.

DISCUSSION

As molecular parasites, viroids require essential host functions for their replication. All viroids require a host RNA-directed RNA polymerase to generate multimeric RNA replication intermediates of minus and plus polarity as well as a host ligase to yield the final circular progeny. In between, the multimeric RNA must be cleaved. Avsunviroidae encode their own ribozymes, while Pospiviroidae rely on a host endonuclease. If, as speculated, viroids originated in the RNA world (52), one might expect versions of RNA replication and maturation activities that support viroid replication in all kingdoms of life. Currently, viroids are known to occur natively only in plants, while a close relative, hepatitis delta virus, a satellite RNA to hepatitis B virus, is found in animals. However, viroid replication has been introduced into nonconventional host plants, such as Nicotiana and Arabidopsis (19, 53), through adaptive changes or transgenic constructs. Beyond plants, the Maurel and Torchet labs recently showed that ASBVd can be propagated in the nonconventional hosts S. cerevisiae and the cyanobacterium Nostoc, supporting the notion that both eukaryotes and bacteria support viroid replication (47, 54). Here we investigate the expression and processing of PSTVd RNA transcripts in yeast. The ability to observe processing in yeast would allow one to utilize the toolbox of yeast molecular biology to study this pathway.

In contrast to ASBVd, which has plus- and minus-strand ribozymes, for PSTVd (a Pospiviroidae) to be processed in yeast, it must find an endonuclease equivalent to that used in conventional plant hosts. We also sought to address the structural requirements for processing in yeast versus host and nonconventional host plants. Thus, we designed constructs that only fold into distinct RNA conformations in vivo.

RNA construct strategy.

From prior TGGE analysis of in vitro transcripts, it was clear that small differences in both the number of nucleotides duplicated between the 5′ and 3′ ends of larger-than-unit-length PSTVd and the rate of folding greatly influence the structures available to the CCR of the viroid (35, 36). Our analysis centered on three constructs. First, we chose the tetraloop-forming, larger-than-monomer RNA (TL) known to be active in potato nuclear extracts. Second, we looked at a perfect linear monomer RNA (mon) generated by two flanking ribozymes in order to interrogate yeast's ability to ligate RNA should proper precursor cleavage fail. Lastly, we designed a new, larger-than-monomer RNA that folds into a trihelical element (triH) that adds important dimensions to the previous processing approaches. In contrast to the RNAs used by Steger et al. (35) and Baumstark et al. (36, 37), this transcript has a full duplication of the UCCR and thus forms a perfect trihelix element. TGGE analysis indicated that the trihelix is thermodynamically most favored; it can form during or after transcription as well as after thermodynamic pretreatments under equilibrium conditions (data not shown). Furthermore, the trihelix does not present the multiple combinations and permutations of structural elements that are available to two complete repeats, as with the dimer of CEVd used by Gas et al. (55). Lastly, we did not rely on a mechanism for trihelix formation that depends on refolding of hairpin 1 elements through kissing loop interactions as postulated by Gas et al. (39, 48).

Expression and stability of RNAs from constructs in yeast.

All of our constructs showed various degrees of expression, but only the TL construct actively formed circles. Northern blots showed that the 390-nt triH primary transcript was much less prevalent than the TL primary transcript. The mon construct produced only a trace amount of 359-nt exact monomers released from the two ribozymes. The monomer band with an uncleaved 5′ hammerhead ribozyme was more prominent, indicating a stabilizing effect of this 5′-capped Pol II end (Fig. 4). However, this band was still much weaker than that for the TL primary transcript.

Shorter, viroid-specific RNA species were also detected in cells expressing the TL or triH construct, but none was of a size expected for processing into unit-length molecules (Fig. 4). Primer extension confirmed that the 5′ ends of these RNAs varied (Fig. 7), consistent with them being degradation products rather than specific viroid processing products. This is in line with results by Delan-Forino et al. (47), who determined that successful processing of ASBVd plus-strand RNA into circles is paralleled by degradation via the yeast RNA surveillance pathway. Competition between processing and degradation is not unique to yeast: recent studies have shown the presence of subgenomic RNA species in PSTVd-infected tobacco, tomato, and eggplant, which may be degradation products created by developmentally regulated endonucleases (49). These subgenomic fragments vary considerably in concentration from one host to another.

Four factors influence the balance between degradation and processing of viroid RNAs in yeast and other systems. (i) An endonuclease(s) recognizes specific structural motifs. (ii) The chemical nature of the endonuclease-produced ends must be compatible with the ligase. (iii) These ends must be presented in a suitable orientation to the ligase, for example, base paired to a continuous complementary strand. (iv) Finally, there must be a thermodynamically feasible pathway to these structures via transient, kinetically favored refolding of nascent RNA. We propose that a fast-forming intermediate is recognized by the endonuclease, which upon cleavage refolds to a lower-free-energy structure recognized by the ligase. The endonuclease substrate folds only when specific end duplications are present, making multimeric viroid RNA a riboswitch sensitive to the context and transcriptional age of the RNA. In the following sections, these factors are discussed in more detail.

Viroid RNAs as endonuclease substrates.

Both longer-than-unit-length transcripts, the triH and TL RNAs, fold so as to be recognized by endonucleases, as indicated by distinct shorter RNA species on Northern blots. The cut triH species were larger than monomeric length, implying either that they would require further cleavage to yield mature circles, which did not form, or that they were already degradation products, similar to the subgenomic PSTVd RNAs observed by Minoia et al. (49). The shorter fragments derived from TL cannot be in the productive processing pathway, as they were shorter than monomeric length. The TL RNA did, however, produce circles in yeast, but these were of aberrant length (367 nt): they contained four nonviroid, vector-derived nucleotides and a four-nucleotide viroid duplication (Fig. 8). Interestingly, no precise linear intermediate could be detected by primer extension (Fig. 7). We conclude that these intermediates are extremely short-lived in yeast: they are either converted to circles immediately or degraded rapidly.

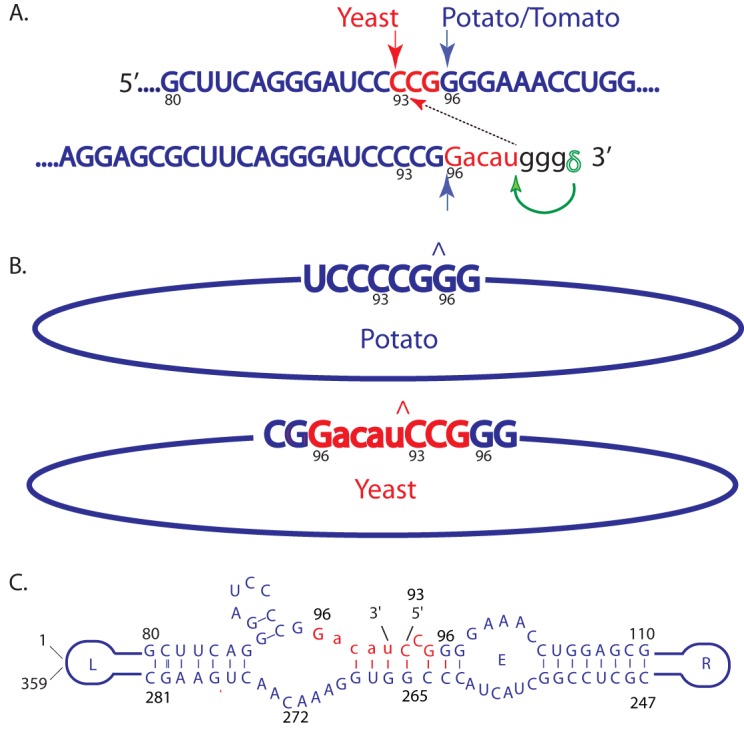

FIG 8.

Cleavage and ligation sites for PSTVd in yeast expressing the TL construct. Letter coloring and upper/lowercase indicate the same nucleotides throughout. The lowercase red letters are vector nucleotides added during plasmid construction. (A) Sequences of the 5′ and 3′ ends of TL transcribed in yeast. Uppercase blue and red letters are wild-type PSTVd sequences. The blue arrows (95/96) indicate the known cleavage sites of PSTVd processed in potato or tomato. The downward-facing red arrow (92/93) indicates the 5′ cleavage site of processing in yeast. The lowercase black letters are the 5′ end of the delta ribozyme. The green arrow indicates cleavage by the delta ribozyme. The dotted line with the red arrow marks the site for ligation in yeast. (B) Sequences of ligation junctions in potato and yeast. A caret (∧) marks the ligation site. Sequences shown were determined by RT-PCR with gel-extracted RNA circles from yeast and tomato. The proposed ligation scheme results in an additional 8 nt in yeast (red). (C) Ligation substrate in yeast. The marked 3′ and 5′ ends are ligated to form the yeast circle. The additional 8 nt (red) comprise nt 96, the four vector nucleotides, and nt 93 to 95.

Circles were not produced by the triH construct. If the same position 92/93 cleavage site were used in the triH construct, both strands would need to be cleaved within the double-stranded trihelix to produce a four-base 5′ overhang. This intermediate would have to refold in order to be ligated into circles. The lack of a detectable productive intermediate for this construct cannot be explained by rapid ligation of the ends, as no circles were observed. Thus, we conclude that yeast has an endonuclease that recognizes and cleaves a structure specific to TL RNA but that this endonuclease does not recognize and cleave triH RNA at the same location.

Nature of the endonuclease.

Cleavage site recognition by an endonuclease typically relies on RNA secondary and tertiary structures rather than the exact sequence (56). Early in vitro processing studies by Tsagris and coworkers showed that the fungal endonuclease RNase T1 cleaved and ligated greater-than-unit-length PSTVd into circles (57, 58) by utilizing single-stranded guanines embedded in a specific structural context (35). The work of Gas et al. (39, 48) provided evidence implicating dicer-like RNase III as the endonuclease that processes CEVd in Arabidopsis thaliana to generate 5′-phosphate and 3′-OH termini.

RNase III endonucleases are involved in rRNA, snRNA, and snoRNA processing, mRNA maturation, RNA silencing, and transcriptome surveillance (59, 60). They typically recognize and interact with their RNAs in a sequence-nonspecific manner and may rely on additional protein components in a complex to create specificity (61). Such protein factors may be responsible for recognition changes from one host to another. In yeast, the sole RNase III enzyme is the Rnt1 protein, which prefers substrates with a variety of RNA hairpins capped by small loops over long RNA double strands (62–64). The GAAA tetraloop within the TL RNA element (Fig. 1) does not conform to the most preferred AAGU or NGNN tetraloop substrates of Rnt1p, and the 92/93 cleavage site is closer to the capping loop than the expected 12 to 14 nt (65). However, the new site is farther from the loop than the site utilized in potato, and this site is at the bottom of the stem predicted by RNA folding programs (36). Given its wide range of targets in RNA metabolism, it cannot be ruled out that Rnt1p is responsible for generating the 5′ cleavage in the TL RNA at position 92/93 that leads to processing into circles. The lack of productive processing products for the triH RNA expressed in yeast (Fig. 3, 4, and 7) implies that the imperfectly double-stranded trihelix is not a substrate for Saccharomyces Rnt1p. Suppression of degradation in a RAT1-107 background led to increased accumulation of linear products for both the TL and triH constructs, but this still did not result in circle production in the case of the trihelix RNA (Fig. 6).

Nature of the ligase.

RNA endonucleases produce ends with either a 3′-OH and a 5′-phosphate or a 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH. Various RNA ligases can utilize either pair of ends. RNA ligases that directly link a 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate and a 5′-OH are found only in archaea and vertebrates. However, yeast and plant tRNA ligases accept 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate and 5′-OH termini, which they convert to 3′-OH and a 5′-phosphate with the help of a distinct 2′-phosphatase (66, 67).

Investigators using different viroids and different hosts see different endonuclease-ligase pairings. Nohales et al. (68) have shown that, in tomato, DNA ligase 1 is redirected to act on PSTVd RNA with 3′-OH and 5′-phosphate ends. They also demonstrated that chloroplast tRNA ligase circularizes each of the four Avsunviroidae RNAs with 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate and 5′-OH termini and that tobacco infected by both eggplant latent viroid (ELVd) and PSTVd stops circularizing ELVd RNA only when its chloroplast tRNA ligase is inhibited (13). Notably, the position of the nick in the double-stranded RNA substrate strongly affects the efficiency of the ligation for both DNA ligase 1 and tRNA ligase (13, 68). CEVd RNA transgenically expressed in Arabidopsis thaliana is processed via cleavage at position 95/96 to give 5′-phosphate and 3′-OH termini (48). However, the same work showed that monomeric linear CEVd isolated from the host Gynura plant had 5′-OH and 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate termini. Finally, Feldstein et al. (19) expressed an exact minus-strand PSTVd monomer with 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate and 5′-OH ends at position 91/92 in Nicotiana benthamiana. This RNA was infectious and gave rise to minus-strand unit-length circles, presumably sealed by a tRNA ligase rather than the DNA ligase proposed for natural PSTVd infection (68).

We observed that yeast processes PSTVd TL RNA into circles. The sequence indicates that the end produced by the delta ribozyme, a 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate, condenses with the end produced by the endonuclease cutting at position 92/93. The simplest explanation is that a tRNA ligase-like enzyme does the ligation; however, the cyclic phosphate could be removed to enable ligation to a 5′-phosphate by a redirected DNA ligase. Why does the monomer RNA released from the double-ribozyme cassette, which contains the exact same end groups, not ligate? This may be an example of the ligase being able to act only at specific locations, which do not include position 95/96. On the other hand, if the host endonuclease creates a 5′-phosphate, the 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate would first have to be hydrolyzed. Low efficiency of this step would contribute to the relatively small amounts of circles produced in our yeast system. In this scenario, the monomer produced by the ribozymes might not be a ligation substrate because the 2′-3′-cyclic phosphate hydrolysis or 5′-OH phosphorylation does not occur for G95/G96 ends or is too slow to compete with degradation. Support for competition with degradation is provided by our observation that the fully cleaved monomer RNA in vivo has a lower concentration than the intermediate with the 5′ ribozyme still attached, in contrast to similar concentrations observed for in vitro transcription (Fig. 4, lanes 9 and 10).

In this regard, ligation of the TL construct can be interpreted as utilization of an “end of convenience” provided by the delta ribozyme. Figure 8C presents a particular pairing of the upper and lower CCRs of the proposed linear TL processing intermediate, containing the two four-nucleotide additions, that would provide a reasonable substrate for an RNA ligase. In this case, the 3′ vector-derived nucleotides are base paired next to the 5′ C93 resulting from yeast endonuclease cleavage. Importantly, this arrangement keeps the upper and lower strands of loop E in register, so it can still contribute to a stable conformation required for ligation. With the current constructs, whether an exact monomer with open ends between C92 and C93 and no extra sequence would be ligated similarly to the TL RNA or degraded as in the case of the monomer with a G95/G96 nick remains unresolved.

The incorporation of extra sequence into aberrant circles is not unique to the TL construct expressed in yeast. Metastable in vitro transcripts of TL RNA incubated in potato nuclear extracts also showed larger-than-unit-length circles, with an efficiency comparable to that for the production of correct, 359-nt viroid circles (37). These circles contained a duplication of 16 viroid nucleotides as the result of a premature conformational switch.

Conclusions.

Our results from PSTVd expression studies with the nonconventional host S. cerevisiae continue to expand our understanding of how viroids have adapted and thrived in a variety of natural and nontraditional hosts. Viroids have shown a unique plasticity to present themselves as substrates for the cell's promiscuous RNA metabolism and to replicate where they encounter the appropriate types of RNA polymerase, endonuclease, and DNA or tRNA ligase. All viroids have to overcome the challenge of evading RNA degradation, as they must rely on endonucleases for productive processing that are possibly part of the very same decay pathways they need to avoid. At the same time, the products of these degradation pathways may be utilized to act as viroid-specific small RNAs (vsRNA) to subvert the plant defense systems via transcriptional and posttranscriptional gene silencing (7, 69).

The evolutionary success of viroids appears to be a variation of two strategies: (i) offering recognition elements, such as hairpins and other local structures, that direct the appropriate nuclease to a preferred location; and (ii) applying RNA refolding between cleavage and ligation steps such that kinetically formed metastable intermediates rearrange to thermodynamically stable end products that are no longer efficient substrates for further cleavage or degradation. From one host cell to another, a particular structure that contributes productively toward generation of circular progeny in one host may not find a favorable use in a different host and thus be channeled toward degradation instead of productive processing. The precise sequence of most suitable structures for both cleavage and subsequent ligation and the type of host enzymes involved in their recognition may vary from system to system. The fact that this has been demonstrated for a growing number of viroids and hosts, such as Arabidopsis, tobacco, potato, eggplant, cyanobacteria, and yeast, underscores the underlying power and adaptability of the viroid RNA replication strategy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, cell growth, and transformation.

The yeast strain YPH500 (MATα URA3-52 LYS2-801 ADE2-101 TRP1-Δ63 HIS3-Δ LEU2-Δ1) was used throughout the study. Yeast cultures were grown at 30°C in synthetic media containing either 2% glucose or 2% galactose for suppression or stimulation of the promoter. Tryptophan was not added to the media for plasmid maintenance. Transformations were carried out using a Frozen-EZ yeast transformation II kit from Zymo Research. A RAT1 mutant strain was also used in this study. The plasmid for creation of the RAT1-107 allele (A661E) was a gift from Eric Phizicky (51). The RAT1-107 gene along with a URA3 fragment of plasmid was digested with AatII and BamHI, run in an agarose gel, and excised. The excised fragment was transformed into YPH500. Colonies that grew on uracil dropout medium were screened for RAT1-107 by PCR and confirmed by sequencing.

Oligonucleotides and plasmids for yeast in vivo expression and in vitro transcripts.

Oligonucleotides were obtained from Invitrogen and are listed in Table 1. The PSTVd sequence used was that for the intermediate strain; its numbering follows that of Gross et al. (22). Each yeast construct had a plasmid used to make a PCR template for in vitro transcripts (IVTs) and a plasmid for expression of the PSTVd RNA in yeast. Plasmids are listed in Table 2. Plasmid TBO110 contains the TL PSTVd construct and has been described previously (36). Plasmid pTBO112 was made in the same manner, except that it contains the triH PSTVd sequences shown in Fig. 1C. IVT PSTVd RNAs and probes for Northern blotting were made by PCR amplifying templates by use of the primers and plasmids indicated in Table 3. The template for RNA pTB112 was cut with EcoRI prior to T7 transcription.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotidea | Sequence (5′–3′)b |

|---|---|

| 112F | ACTGGCAAAAAGGACGGTGGGGA |

| 259R | GTAGCCGAAGCGACAGCGCAAAGG |

| 2F | CCTGTGGTTCACACCTGACCTCC |

| MB1R | TCGGCCGCTGGGCACTCC |

| ActF | GGTATTCTCACCAACTGGGACG |

| M13 F | GTAAAACGACGGCCAG |

| M13 R | CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC |

| T7 prom F | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATA |

| TB110 down R | AATTCCGGGGATCCCTGAAGCGCTCC |

| T7 prom F | GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATA |

| TB112 down R | GCCACCTGACGTCTAAGAAACC |

| T7ActR | GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCGACGTAACATACTTTTTCCTGATGT |

| SCR1F | TGGCCGAGGAACAAATCCTT |

| T7ScR1R | GTAATACGACTCACTATAGTTAAACCGCCGAAGCGATCA |

| T7 PSTVd dim F | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGTACGTACTG |

| PSTVd dim R | GGGACAGAGGTCCTCAG |

Forward primers (names ending in “F”) have the same sequence as the transcribed RNA.

Italicized letters indicate the introduced T7 promoter sequence.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Constructa | RNA | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| p13/119 | Monomer IVT | This work | |

| pB3RQ39 | PGAL1-BMV-RNA3-δ | BMV-RNA3 | 70 |

| pCR2.1_TOPO.4 | HH-95/96 monomer-HP | Monomer | 19 |

| pTB110 | Parent pRH701 | TL IVT | 36 |

| pTB112 | PSTVd trihelix | triH IVT | This work |

| pTBO_mon | PGAL1-HH-PSTVd monomer-HP | TBO_Mon | This work |

| pTBO_TL | PGAL1-PSTVd tetraloop-δ | TBO_TL | This work |

| pTBO_triH | PGAL1-PSTVd trihelix-δ | TBO_triH | This work |

| pIC115 | RAT1-107::URA3 | RAT1-107::URA3 | 48 |

PGAL1, full GAL1 promoter; δ, delta ribozyme; HH, hammerhead ribozyme; HP, hairpin ribozyme.

TABLE 3.

Templates for IVT PSTVd RNAs and riboprobes

| RNA | Template | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| TL IVT | pTB110 | T7 prom F | TB110 down R |

| triH IVT | pTB112 | T7 prom F | TB112 down R |

| Monomer IVT | p13/119 | M13 F | M13 R |

| (−)-sense PSTVd riboprobe | p13/121 | M13 F | M13 R |

| (−)-sense actin | YPH500 genome | ActF | T7ActR |

| (−)-sense SCR1 | YPH500 genome | SCR1F | T7ScR1R |

The PSTVd yeast expression constructs were all cloned into the yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle plasmid pB3RQ39 (TRP1 CEN4 GAL1 promoter), which expresses brome mosaic virus (BMV) RNA (46, 70). The BMV sequence was excised using restriction enzymes SnaB1 and PshA1 and replaced with PSTVd sequences such that each sequence was under the control of the GAL1 promoter and followed by the hepatitis delta virus ribozyme. This allows galactose to induce the RNA, and ribozyme cleavage creates a precise 3′ end after the PSTVd sequence (46). Insertion of the tetraloop sequence from pTB110 (36) and the trihelix sequence from pTB112 gave pTBO_TL and pTBO_triH, respectively. For the monomer, the exact position 95/96-opened monomer flanked by the 5′ hammerhead ribozyme and a 3′ hairpin ribozyme was subcloned from pCR2.1-TOPO.4 (19) into pB3RQ39 so as to replace both BMV and the delta ribozyme to create plasmid pTBO_mon. The sequences of the three PSTVd constructs with flanking ribozymes are given in Supplemental file S1 in the supplemental material.

RNA extraction.

Yeast containing the appropriate plasmid was grown in selective medium to an optical density (OD) of 0.6 to 1.0. Total RNA was extracted from cells at 10 OD/ml by using the hot phenol extraction method (71).

RT-PCR for detection of plus-sense PSTVd and PSTVd circles.

One-microgram aliquots of total RNA were treated with DNase I (Invitrogen). The RNA was then phenol-chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated. Three nanograms of DNase-treated total RNA was subject to reverse transcription (Superscript III; Invitrogen), using 20 pmol of primer 259R in 10 μl of reaction mixture (Table 1). One-tenth of the product was used for PCR amplification. The amplifications were carried out in 12.5 μl of 2× Go Taq (Promega) with 25 pmol (each) of the following primers: 259R/112F for plus-sense PSTVd and 259R/2F for circles. The following program was run on an Eppendorf thermocycler: 5 min at 95°C and 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 40 s at 64°C, and 60 s at 72°C, followed by 5 min at 72°C and a hold at 4°C. Amplification products were separated in a 5% polyacrylamide (PAA)-8 M urea gel and visualized by silver staining (72).

Gel purification of linear and circular PSTVd.

A total of 5 μg RNA was run in a 5% denaturing PAA gel along with RNAs from infected tomato to provide migration markers for linear and circular plus-sense PSTVd RNAs. RNAs corresponding to linear and circular molecules were cut from the gel, and the RNAs were eluted by soaking the excised bands in gel elution buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% SDS). The samples were then frozen, thawed, and incubated with shaking overnight at 4°C. The supernatant was then removed, and another aliquot of gel elution buffer was added and the mixture allowed to shake for 2 h. The combined supernatants were phenol-chloroform extracted and then precipitated with ethanol. The extracted RNAs were then subjected to RT-PCR for detection of plus-sense PSTVd and PSTVd circles. After 5% PAA gel detection and confirmation, the RT-PCR products were cleaned by use of a Promega PCR clean-up kit. The resulting DNA was sent to the Yale Sequencing Center for final sequencing. The primers used for sequencing of the ligation junction were 2F and 259R (Table 1).

RNA detection by Northern blotting.

Total RNAs (5 μg) were separated in a 5% PAA-8 M urea gel and semidry electroblotted to a Hybond N+ membrane (GE Healthcare). The membranes were incubated in UltraHyb solution (Ambion) overnight at 65°C with the appropriate riboprobe and then washed with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.1% SDS. Four 65°C washes were performed (2 for 10 min each and 2 for 20 min each). The membranes were imaged using phosphorimager screens and measured with a Storm 840 phosphorimager (GE Healthcare). IVT PSTVd controls and riboprobes for detection of PSTVd, actin, and SCR1 (73) were generated as described in Table 3. Radioactive labeling was performed with [α-32P]UTP or [α-32P]CTP (PerkinElmer).

Manganese chloride treatment of total yeast RNA to enrich small RNAs.

For enrichment of viroid linear intermediates, total RNAs from yeast were treated with MnCl2 according to the method of Semancik and Szychowski (50). RNA solutions (100 ng/μl) were treated with 50 mM MnCl2 in 0.1× Tris-EDTA (TE). After incubation at 4°C, the solution was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant containing the small RNA fraction was then ethanol precipitated.

Primer extension.

Oligonucleotide M1BR (Table 1) binds plus-strand PSTVd at positions 150 to 133. The primer was 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by use of T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen). Approximately 106 cpm of this primer was annealed to 25 μg of total RNA from yeast, 12.5 μg of manganese-treated RNA from yeast, and 0.5 pmol of viroid in vitro transcript. The extension was conducted using 100 U of reverse transcriptase (Superscript III; Invitrogen). After extension for 90 min at 52°C, the reaction was stopped and the products were ethanol precipitated. A DNA sequencing ladder was generated using primer M1BR and a PCR fragment encompassing the PSTVd sequence from the plasmid harboring the trihelix sequence. The ladder was formed using a Sequitherm cycle sequencing kit (Epicentre Technologies). The products from the primer extension assay and the ladder were separated in 8% (19:1) PAA-8 M urea sequencing gels.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

R. Salvo provided valuable assistance with the primer extension experiments. Rose Hammond provided PSTVd-infected and healthy petunia RNA samples.

D.F. was supported by Campbell Soup Company's tuition reimbursement program. The Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry at the University of the Sciences funded this project.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01078-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diener TO. 1972. Viroids. Adv Virus Res 17:295–313. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60754-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diener TO. 1974. Viroids: the smallest known agents of infectious disease. Annu Rev Microbiol 28:23–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.28.100174.000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsagris EM, Martinez de Alba AE, Gozmanova M, Kalantidis K. 2008. Viroids. Cell Microbiol 10:2168–2179. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flores R, Minoia S, Carbonell A, Gisel A, Delgado S, Lopez-Carrasco A, Navarro B, Di Serio F. 2015. Viroids, the simplest RNA replicons: how they manipulate their hosts for being propagated and how their hosts react for containing the infection. Virus Res 209:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owens RA, Hammond RW. 2009. Viroid pathogenicity: one process, many faces. Viruses 1:298–316. doi: 10.3390/v1020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gago S, Elena SF, Flores R, Sanjuan R. 2009. Extremely high mutation rate of a hammerhead viroid. Science 323:1308. doi: 10.1126/science.1169202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding B. 2010. Viroids: self-replicating, mobile, and fast-evolving noncoding regulatory RNAs. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 1:362–375. doi: 10.1002/wrna.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro JA, Vera A, Flores R. 2000. A chloroplastic RNA polymerase resistant to tagetitoxin is involved in replication of avocado sunblotch viroid. Virology 268:218–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores R, Serra P, Minoia S, Di Serio F, Navarro B. 2012. Viroids: from genotype to phenotype just relying on RNA sequence and structural motifs. Front Microbiol 3:217. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchins CJ, Rathjen PD, Forster AC, Symons RH. 1986. Self-cleavage of plus and minus RNA transcripts of avocado sunblotch viroid. Nucleic Acids Res 14:3627–3640. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.9.3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daros JA, Marcos JF, Hernandez C, Flores R. 1994. Replication of avocado sunblotch viroid: evidence for a symmetric pathway with two rolling circles and hammerhead ribozyme processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:12813–12817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flores R, Daros JA, Hernandez C. 2000. Avsunviroidae family: viroids containing hammerhead ribozymes. Adv Virus Res 55:271–323. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(00)55006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nohales MA, Molina-Serrano D, Flores R, Daros JA. 2012. Involvement of the chloroplastic isoform of tRNA ligase in the replication of viroids belonging to the family Avsunviroidae. J Virol 86:8269–8276. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00629-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owens RA. 2007. Potato spindle tuber viroid: the simplicity paradox resolved? Mol Plant Pathol 8:549–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman TC, Nagel L, Rappold W, Klotz G, Riesner D. 1984. Viroid replication: equilibrium association constant and comparative activity measurements for the viroid-polymerase interaction. Nucleic Acids Res 12:6231–6246. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.15.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolonko N, Bannach O, Aschermann K, Hu KH, Moors M, Schmitz M, Steger G, Riesner D. 2006. Transcription of potato spindle tuber viroid by RNA polymerase II starts in the left terminal loop. Virology 347:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Branch AD, Benenfeld BJ, Robertson HD. 1988. Evidence for a single rolling circle in the replication of potato spindle tuber viroid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85:9128–9132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsagris M, Tabler M, Sanger HL. 1987. Oligomeric potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTV) RNA does not process autocatalytically under conditions where other RNAs do. Virology 157:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldstein PA, Hu Y, Owens RA. 1998. Precisely full length, circularizable, complementary RNA: an infectious form of potato spindle tuber viroid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:6560–6565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flores R, Gas ME, Molina-Serrano D, Nohales MA, Carbonell A, Gago S, De la Pena M, Daros JA. 2009. Viroid replication: rolling-circles, enzymes and ribozymes. Viruses 1:317–334. doi: 10.3390/v1020317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Branch AD, Robertson HD. 1984. A replication cycle for viroids and other small infectious RNA's. Science 223:450–455. doi: 10.1126/science.6197756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross HJ, Domdey H, Lossow C, Jank P, Raba M, Alberty H, Sanger HL. 1978. Nucleotide sequence and secondary structure of potato spindle tuber viroid. Nature 273:203–208. doi: 10.1038/273203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keese P, Symons RH. 1985. Domains in viroids: evidence of intermolecular RNA rearrangements and their contribution to viroid evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82:4582–4586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabler M, Sanger HL. 1984. Cloned single- and double-stranded DNA copies of potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTV) RNA and co-inoculated subgenomic DNA fragments are infectious. EMBO J 3:3055–3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishikawa M, Meshi T, Ohno T, Okada Y, Sano T, Ueda I, Shikata E. 1984. A revised replication cycle for viroids: the role of longer than unit length RNA in viroid replication. Mol Gen Genet 196:421–428. doi: 10.1007/BF00436189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meshi T, Ishikawa M, Ohno T, Okada Y, Sano T, Ueda I, Shikata E. 1984. Double-stranded cDNAs of hop stunt viroid are infectious. J Biochem 95:1521–1524. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabler M, Sanger HL. 1985. Infectivity studies on different potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTV) RNAs synthesized in vitro with the SP6 transcription system. EMBO J 4:2191–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Candresse T, Diener TO, Owens RA. 1990. The role of the viroid central conserved region in cDNA infectivity. Virology 175:232–237. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rakowski AG, Symons RH. 1994. Infectivity of linear monomeric transcripts of citrus exocortis viroid: terminal sequence requirements for processing. Virology 203:328–335. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henco K, Sanger HL, Riesner D. 1979. Fine structure melting of viroids as studied by kinetic methods. Nucleic Acids Res 6:3041–3059. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.9.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diener TO. 1986. Viroid processing: a model involving the central conserved region and hairpin I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83:58–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visvader JE, Forster AC, Symons RH. 1985. Infectivity and in vitro mutagenesis of monomeric cDNA clones of citrus exocortis viroid indicates the site of processing of viroid precursors. Nucleic Acids Res 13:5843–5856. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.16.5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steger G, Tabler M, Bruggemann W, Colpan M, Klotz G, Sanger HL, Riesner D. 1986. Structure of viroid replicative intermediates: physico-chemical studies on SP6 transcripts of cloned oligomeric potato spindle tuber viroid. Nucleic Acids Res 14:9613–9630. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.24.9613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gast FU, Kempe D, Sanger HL. 1998. The dimerization domain of potato spindle tuber viroid, a possible hallmark for infectious RNA. Biochemistry 37:14098–14107. doi: 10.1021/bi980830d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steger G, Baumstark T, Morchen M, Tabler M, Tsagris M, Sanger HL, Riesner D. 1992. Structural requirements for viroid processing by RNase T1. J Mol Biol 227:719–737. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90220-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumstark T, Riesner D. 1995. Only one of four possible secondary structures of the central conserved region of potato spindle tuber viroid is a substrate for processing in a potato nuclear extract. Nucleic Acids Res 23:4246–4254. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumstark T, Schroder AR, Riesner D. 1997. Viroid processing: switch from cleavage to ligation is driven by a change from a tetraloop to a loop E conformation. EMBO J 16:599–610. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrader O, Baumstark T, Riesner D. 2003. A mini-RNA containing the tetraloop, wobble-pair and loop E motifs of the central conserved region of potato spindle tuber viroid is processed into a minicircle. Nucleic Acids Res 31:988–998. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gas ME, Hernandez C, Flores R, Daros JA. 2007. Processing of nuclear viroids in vivo: an interplay between RNA conformations. PLoS Pathog 3:e182. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Owens RA, Baumstark T. 2007. Structural differences within the loop E motif imply alternative mechanisms of viroid processing. RNA 13:824–834. doi: 10.1261/rna.452307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong X, Archual AJ, Amin AA, Ding B. 2008. A genomic map of viroid RNA motifs critical for replication and systemic trafficking. Plant Cell 20:35–47. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding B. 2009. The biology of viroid-host interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol 47:105–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Botstein D, Fink GR. 1988. Yeast: an experimental organism for modern biology. Science 240:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.3287619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnston JR. 1994. Molecular genetics of yeast: a practical approach. IRL Press at Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia-Ruiz H, Ahlquist P. 2006. Inducible yeast system for viral RNA recombination reveals requirement for an RNA replication signal on both parental RNAs. J Virol 80:8316–8328. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01790-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quadt R, Ishikawa M, Janda M, Ahlquist P. 1995. Formation of brome mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in yeast requires coexpression of viral proteins and viral RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:4892–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delan-Forino C, Maurel MC, Torchet C. 2011. Replication of avocado sunblotch viroid in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Virol 85:3229–3238. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01320-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gas ME, Molina-Serrano D, Hernandez C, Flores R, Daros JA. 2008. Monomeric linear RNA of citrus exocortis viroid resulting from processing in vivo has 5′-phosphomonoester and 3′-hydroxyl termini: implications for the RNase and RNA ligase involved in replication. J Virol 82:10321–10325. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01229-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minoia S, Navarro B, Delgado S, Di Serio F, Flores R. 2015. Viroid RNA turnover: characterization of the subgenomic RNAs of potato spindle tuber viroid accumulating in infected tissues provides insights into decay pathways operating in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res 43:2313–2325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Semancik JS, Szychowski J. 1983. Enhanced detection of viroid-RNA after selective divalent cation fractionation. Anal Biochem 135:275–279. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90683-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chernyakov I, Whipple JM, Kotelawala L, Grayhack EJ, Phizicky EM. 2008. Degradation of several hypomodified mature tRNA species in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is mediated by Met22 and the 5′-3′ exonucleases Rat1 and Xrn1. Genes Dev 22:1369–1380. doi: 10.1101/gad.1654308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diener TO. 2016. Viroids: “living fossils” of primordial RNAs? Biol Direct 11:15. doi: 10.1186/s13062-016-0116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daros JA, Flores R. 2004. Arabidopsis thaliana has the enzymatic machinery for replicating representative viroid species of the family Pospiviroidae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:6792–6797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401090101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Latifi A, Bernard C, da Silva L, Andéol Y, Elleuch A, Risoul V, Vergne J, Maurel C. 2016. Replication of avocado sunblotch viroid in the cyanobacterium Nostoc sp. PCC 7120. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 7:341. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hecker R, Wang ZM, Steger G, Riesner D. 1988. Analysis of RNA structures by temperature-gradient gel electrophoresis: viroid replication and processing. Gene 72:59–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90128-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glow D, Nowacka M, Skowronek KJ, Bujnicki JM. 2016. Sequence-specific endoribonucleases. Postepy Biochem 62:303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsagris M, Tabler M, Sanger HL. 1991. Ribonuclease T1 generates circular RNA molecules from viroid-specific RNA transcripts by cleavage and intramolecular ligation. Nucleic Acids Res 19:1605–1612. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.7.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tabler M, Tzortzakaki S, Tsagris M. 1992. Processing of linear longer-than-unit-length potato spindle tuber viroid RNAs into infectious monomeric circular molecules by a G-specific endoribonuclease. Virology 190:746–753. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conrad C, Rauhut R. 2002. Ribonuclease III: new sense from nuisance. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 34:116–129. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gagnon J, Lavoie M, Catala M, Malenfant F, Elela SA. 2015. Transcriptome wide annotation of eukaryotic RNase III reactivity and degradation signals. PLoS Genet 11:e1005000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.MacRae IJ, Zhou K, Doudna JA. 2007. Structural determinants of RNA recognition and cleavage by Dicer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14:934–940. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chanfreau G, Buckle M, Jacquier A. 2000. Recognition of a conserved class of RNA tetraloops by Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase III. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:3142–3147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagel R, Ares M. 2000. Substrate recognition by a eukaryotic RNase III: the double-stranded RNA-binding domain of Rnt1p selectively binds RNA containing a 5′-AGNN-3′ tetraloop. RNA 6:1142–1156. doi: 10.1017/S1355838200000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lamontagne B, Elela SA. 2004. Evaluation of the RNA determinants for bacterial and yeast RNase III binding and cleavage. J Biol Chem 279:2231–2241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Hartman E, Roy K, Chanfreau G, Feigon J. 2011. Structure of a yeast RNase III dsRBD complex with a noncanonical RNA substrate provides new insights into binding specificity of dsRBDs. Structure 19:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Popow J, Schleiffer A, Martinez J. 2012. Diversity and roles of (t)RNA ligases. Cell Mol Life Sci 69:2657–2670. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0944-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abelson J, Trotta CR, Li H. 1998. tRNA splicing. J Biol Chem 273:12685–12688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nohales MA, Flores R, Daros JA. 2012. Viroid RNA redirects host DNA ligase 1 to act as an RNA ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:13805–13810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206187109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hammann C, Steger G. 2012. Viroid-specific small RNA in plant disease. RNA Biol 9:809–819. doi: 10.4161/rna.19810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ishikawa M, Janda M, Krol MA, Ahlquist P. 1997. In vivo DNA expression of functional brome mosaic virus RNA replicons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Virol 71:7781–7790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Köhrer K, Domdey H. 1991. Preparation of high molecular weight RNA. Methods Enzymol 194:398–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94030-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chevallet M, Luche S, Rabilloud T. 2006. Silver staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Nat Protoc 1:1852–1858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maderazo AB, Belk JP, He F, Jacobson A. 2003. Nonsense-containing mRNAs that accumulate in the absence of a functional nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway are destabilized rapidly upon its restitution. Mol Cell Biol 23:842–851. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.842-851.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.