Abstract

Background

The extent of metabolic and lipid changes in first-episode psychosis (FEP) is unclear.

Aims

To investigate whether individuals with FEP and no or minimal antipsychotic exposure show lipid and adipocytokine abnormalities compared with healthy controls.

Method

We conducted a meta-analysis of studies examining lipid and adipocytokine parameters in individuals with FEP and no or minimal antipsychotic exposure v. a healthy control group. Studies reported fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides and leptin levels.

Results

Of 2070 citations retrieved, 20 case-control studies met inclusion criteria including 1167 patients and 1184 controls. Total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels were significantly decreased in patients v. controls, corresponding to an absolute reduction of 0.26 mmol/L and 0.15 mmol/L respectively. Triglyceride levels were significantly increased in the patient group, corresponding to an absolute increase of 0.08 mmol/L. However, HDL cholesterol and leptin levels were not altered in patients v. controls.

Conclusions

Total and LDL cholesterol levels are reduced in FEP, indicating that hypercholesterolaemia in patients with chronic disorder is secondary and potentially modifiable. In contrast, triglycerides are elevated in FEP. Hypertriglyceridaemia is a feature of type 2 diabetes mellitus, therefore this finding adds to the evidence for glucose dysregulation in this cohort. These findings support early intervention targeting nutrition, physical activity and appropriate antipsychotic prescription.

Individuals with schizophrenia die 15–20 years earlier than the general population, with 60% or more of this premature mortality due to physical illness, predominantly cardiovascular disease.1–6 The metabolic syndrome describes a cluster of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including dyslipidaemia, hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance/type 2 diabetes mellitus and central obesity.7–12 A recent meta-analysis demonstrated across 93 studies that a third of people with schizophrenia have metabolic syndrome, with rates as high as 69% in those with chronic illness.13 The odds ratio (OR) of metabolic syndrome in chronic schizophrenia compared with the general population is 2.35 (95% CI 1.68–2.39).14 Chronic schizophrenia is associated with lipid disorder, specifically reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with population controls (OR = 2.35, 95% CI 1.78–3.10) and raised triglyceride levels (OR = 2.73, 95% CI 1.95–3.83).14 Although antipsychotic treatment could contribute to this, several studies have found evidence for alterations in lipids at illness onset,15–20 suggesting that alterations might be intrinsic to schizophrenia. Perry et al recently conducted a meta-analysis examining glucose dysregulation in patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) and in subgroup analyses explored differences in lipid parameters between FEP and healthy control groups.21 However, their meta-analysis did not systematically search for studies examining lipid parameters, so key studies may have been missed. Moreover, sensitivity analyses examining parameters known to affect dyslipidaemia were not performed. Furthermore, their meta-analysis did not consider adipocytokines in FEP. In view of this we set out to investigate whether alterations in lipid and adipocytokine parameters are evident in individuals at the onset of psychotic illness, with no or minimal antipsychotic exposure.

Method

A systematic review was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (online supplement DS1).22,23 Two reviewers (T.P. and K.B.) independently searched Medline (from 1946 to 14 December 2016), EMBASE (from 1947 to 2016, week 50) and PsycINFO (from 1806 to December 2016, week 1). These databases were selected because they comprehensively cover psychiatric and medical journals likely to publish studies on this topic, and are consistent with previous meta-analyses in the field focusing on metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular disease risk factors in psychotic illness.24–26 The following keywords were used: (‘schizophrenia’ OR ‘schizo-affective’ OR ‘psychosis’) AND (‘early’ OR ‘first episode’ OR ‘risk’ OR ‘prodrome’) AND (‘metabolic’ OR ‘lipid’ OR ‘cholesterol’ OR ‘HDL’ OR ‘LDL’ OR ‘lipoprotein’ OR ‘triglyceride’ OR ‘adiponectin’ OR ‘ghrelin’ OR ‘leptin’ OR ‘resistin’ OR ‘chemerin’ OR ‘omentin’ OR ‘apelin’ or ‘adipocytokine’ OR ‘adipokine’). This was complemented by hand-searching of meta-analyses and review articles, which are listed in online supplement DS1, together with an a priori protocol. Inclusion criteria were:

a DSM or ICD diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia spectrum or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified or an at-risk mental state for psychosis according to research criteria;27,28

a first episode of illness, defined as either first treatment contact (in-patient or out-patient) or duration of illness up to 5 years following illness onset;29

less than 2 weeks of antipsychotic treatment;

a healthy control group;

lipid profile assessment including one or more of the following measures: total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, adiponectin, ghrelin, leptin, resistin, chemerin, omentin or apelin. Both fasting and non-fasting values were accepted, although all studies included in the analysis recorded fasting parameters.

Further information regarding rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in online supplement DS1. Studies in any language were considered. No restriction was made with regard to study design. Exclusion criteria were:

study not reporting absolute values (i.e. studies that only provided data regarding the dichotomous presence or absence of raised lipid parameters as defined by diagnostic criteria);7–10

sample including patients with multiple episodes of schizophrenia;

chronic antipsychotic treatment (more than 2 weeks' lifetime exposure);

substance- or medication-induced psychotic disorder;

physical comorbidity that might affect lipid homeostasis (e.g. familial hypercholesterolaemia, thyroid dysfunction, nephrotic syndrome);

absence of measures in a healthy control group.

Data extraction

Screening based on title and abstract was performed independently by two authors (T.P. and K.B.). Where full texts, abstracts or group estimate data were not available, authors were contacted and articles or data requested. We allowed 4 weeks for authors to respond, with repeat contact attempts made after 2 weeks. Data extraction was performed independently (by T.P. and K.B.) and any disagreements resolved by rechecking original articles. Data were extracted according to the following model: author, year of publication, country, type of publication (i.e. prospective, cross-sectional, case–control, retrospective), matching criteria for patients and controls (confirmed by review of study methodology, or by confirmation of non-significance between mean parameter levels of patient and control groups); whether or not patient groups were antipsychotic-naïve (and if not, duration of treatment); and mean (with standard deviation) measure of lipid or adipocytokine parameter in patient and control groups. Where there were multiple publications for the same data-set, data were extracted from the study with the largest data-set. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.30

Statistical analysis

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3.0 was used in all analyses. A two-tailed P value less than 0.05 was deemed significant. A random effects model was used in all analyses owing to an expectation of heterogeneity of data across studies.23 Standardised mean differences in lipid parameters and adipocytokine levels between patient and control cohorts were used as the effect size, using Hedges' adjusted g and 95% confidence intervals. The direction of the effect size was positive if participants with schizophrenia demonstrated higher values of lipid parameters compared with controls. Where significant differences in lipid parameters were demonstrated, absolute differences were also calculated to allow clinical interpretation. Mean differences were calculated using SI units (mmol/L), which for certain studies required conversion from conventional units (mg/dL). To do so we used standardised conversion factors.31 Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using Cochran's Q.32 Inconsistency across studies was assessed with the I2 statistic,33 with a value below 25% deemed to have low heterogeneity, 25–75% medium heterogeneity and above 75% high heterogeneity. Publication bias and selective reporting were assessed using Egger's test of the intercept,34 although this was not calculated when fewer than ten studies were analysed, as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration, and represented diagrammatically with funnel plots, again as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.35

The most common cause of dyslipidaemia is secondary to obesity and high fat intake, particularly saturated fat.36 Age, gender and ethnicity are also recognised to influence lipid parameters.37 To address whether differences in body mass index (BMI), dietary intake, age, gender and ethnicity between patient and control groups influenced results, separate sensitivity analyses examining groups matched for these factors were performed. Matching was confirmed either by review of study method or by calculation of no significant difference between mean parameters in patient and control groups. To investigate further the influence of difference in BMI between patient and control groups on lipid parameter effect size, random effects meta-regression analyses were performed, regressing lipid parameter effect size on difference in BMI between patient and control groups. Meta-regression was not performed when fewer than ten studies were analysed, as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.35 To ensure that findings were not secondary to physical illness in one or both cohorts, sensitivity analyses were performed after removing studies that failed to document whether participants were excluded on the basis of poor physical health.

Results

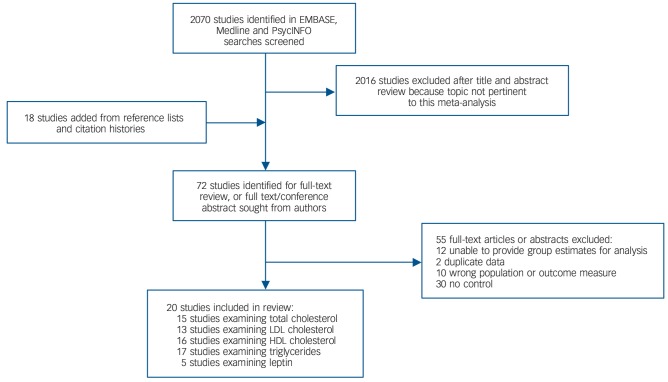

Of 2070 citations retrieved, 20 case-control studies met inclusion criteria.15–20,38–51 The search process is shown in Fig. 1 and the studies finally selected are summarised in Table 1. The overall sample comprised 1167 patients and 1184 controls. The mean age of patients was 27.9 years. Of the 1167 patients, 746 (63.9%) were antipsychotic-naïve whereas 421 (36.1%) had received antipsychotic medication for up to 14 days. There was no study of people with an at-risk mental state. The online data supplement details the raw data for analyses (Tables DS1–8); further information regarding cohort characteristics is given in Table DS9. Forest plots for HDL cholesterol and leptin, funnel plots and scatter plots for the individual lipid parameters are shown in Figs DS1–11.

Fig. 1.

Search process. HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Table 1.

Studies meeting inclusion criteria examining lipid and adipocytokine parameters in first-episode schizophrenia and related disorders

| Setting | Patients n |

DSM diagnoses | Patient age, years: mean (s.d.) |

Control group n |

Lipid parameters |

Antipsychotic status |

Patient BMI, kg/m2: mean (s.d) |

Matching | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al (2016)15 | China | 172 | Schizophrenia | 28.7 (9.9) | 31 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | All naïve | 21.8 (3.8) | BMI, age, ethnicity, gender, smoking |

| Petrikis et al (2015)38 | Greece | 40 | Schizophrenia, schizophreniform, brief psychotic episode |

32.5 (9.8) | 40 | TC, HDL, TG | All naïve | 22.9 (3.7) | BMI, age, gender, smoking |

| Srihari et al (2013)51 | USA | 76 | Schizophrenia, schizophreniform, brief psychotic episode |

22.4 (4.8) | 156 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | 14 days' antipsychotic use |

25.0 (4.0) | Age, gender, ethnicity |

| Enez Darcin et al (2015)39 | Turkey | 40 | Schizophrenia | 34.6 (1.1) | 70 | HDL, TG | All naïve | 24.3 (7.4) | BMI, age, smoking |

| Dasgupta et al (2010)40 | India | 30 | Schizophrenia | 32.5 (10.5) | 25 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | All naïve | 21.0 (3.1) | BMI, age, ethnicity, diet, gender |

| Arranz et al (2004)41 | Spain | 50 | Schizophrenia | 25.2 (0.6) | 50 | Leptin | All naïve | 22.2 (2.1) | BMI, gender |

| Ryan et al (2003)18 | UK/Ireland | 26 | Schizophrenia | 33.6 (13.5) | 26 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | All naïve | 24.5 (3.6) | BMI, age, gender, smoking, diet, exercise |

| Basoglu et al2010)42 | Turkey | 27 | Schizophrenia | 21.2 (0.8) | 22 | LDL, HDL, TG, leptin | All naïve | 22.0 (2.2) | Age, gender, smoking, BMI |

| Kirkpatrick et al (2010)43 | Spain | 87 | Schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, psychosis NOS |

27.1 (5.3) | 92 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | <7 days' antipsychotic use |

22.3 (3.8) | Age, gender, smoking, BMI |

| Spelman et al (2007)44 | Ireland | 38 | Schizophrenia | 25.2 (5.6) | 38 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG, leptin | All naïve | 22.8 (3.1) | Age, gender, smoking ethnicity |

| Wang et al (2007)45 | Taiwan | 16 | Schizophrenia | 25.2 (4.9) | 16 | Leptin | All naïve | 22.3 (3.9) | Age, gender, BMI |

| Saddichha et al (2008)19 | India | 99 | Schizophrenia | 26.0 (5.5) | 51 | HDL, TG | All naïve | NS | Age, gender, diet, exercise |

| Sengupta et al (2008)46 | Canada | 38 | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder | 25.4 (5.6) | 36 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | <10 days' antipsychotic use |

22.8 (3.2) | BMI, age, gender, ethnicity |

| Venkatasubramanian et al (2010)47 | India | 38 | Schizophrenia | 32.2 (7.6) | 38 | TC, TG, leptin | All naïve | 20.0 (3.1) | BMI, age, gender, socio-economic status |

| Chen et al (2016)16 | China | 60 | Schizophrenia | 28.2 (10) | 28 | TC, TG | <14 days' antipsychotic use |

21.9(3.8) | BMI, age, gender, smoking |

| Wu et al (2013)48 | China | 70 | Schizophrenia | 24.5 (7) | 44 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | All naïve | 19.6 (2.5) | BMI, age, gender, ethnicity |

| Verma et al (2009)17 | Singapore | 160 | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder, affective psychosis, psychosis NOS, other psychotic disorders |

30.0 (6.5) | 200 | TC, LDL, HDL | <3 days' total antipsychotic use |

21.2 (3.7) | Age, gender, ethnicity |

| Misiak et al (2016)20 | Poland | 24 | Schizophrenia | 26.8 (2.9) | 146 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | All naïve | 23.0 (2.9) | Age, gender, BMI |

| Sarandol et al (2015)50 | Turkey | 26 | At 6 months a DSM diagnosis of schizophrenia/bipolar affective disorder was made |

25.6 (7.0) | 25 | TC, LDL, HDL, TG | All naïve | 22.0 (3.3) | Age, gender, BMI, smoking |

| Kavzoglu et al (2013)49 | Turkey | 50 | Schizophrenia | 30.1 (7.5) | 50 | TC, HDL, LDL, TG | All naïve | NS | Age, gender, BMI, smoking |

BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NOS, not otherwise specifed. TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

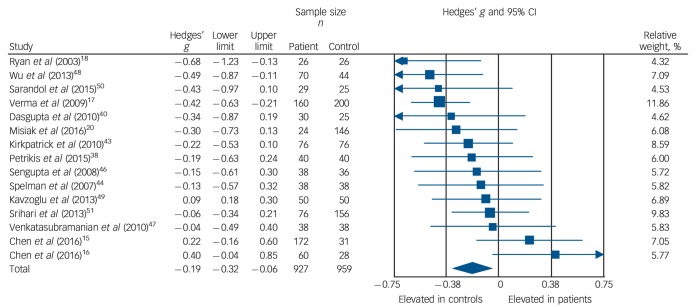

Total cholesterol

Total cholesterol concentration was analysed using data for 15 studies, comprising 927 patients and 959 controls.15–18,20,38,40,43,44,46–51 Total cholesterol levels were significantly decreased in patients compared with controls: g = −0.19, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.06; P = 0.005 (Fig. 2). This corresponds to an absolute decrease in total cholesterol of 0.26 mmol/L. There was significant between-sample heterogeneity, with an I2 of 42% (Q = 24.2, P = 0.04). Findings of Egger's test (P = 0.54) suggested that publication bias was not significant, and visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested symmetry (online Fig. DS3). After restricting analyses to 12 BMI-matched studies,15,16,18,20,38,40,43,46–50 total cholesterol concentration remained significantly decreased in patients (n = 813) compared with controls (n = 765); g = −0.21, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.06; P < 0.01. Meta-regression of effect size for total cholesterol on absolute difference in BMI between patient and control groups (scatter plot shown in online Fig. DS8) revealed that BMI difference between the two cohorts was not a significant moderator of the total cholesterol effect size (β = 0.05, 95% CI −0.30 to 0.40; P = 0.76). There were insufficient studies to perform a sensitivity analysis where groups were matched for dietary intake. After restricting analyses to seven studies matched for ethnicity,15,17,18,40,44,46,51 there was no longer a significant difference in total cholesterol between patients (n = 540) and controls (n = 512): g = −0.21, 95% CI −0.42 to 0.00; P = 0.05. After exclusion of two studies in which participants were not specifically documented as being physically healthy,17,51 total cholesterol concentration remained significantly decreased in patients (n = 691) and controls (n = 603): g = −0.17, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.02; P = 0.02. All studies involved in the total cholesterol analysis were matched for age and gender and therefore these sensitivity analyses were not required.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing total cholesterol concentration in patients with first-episode psychosis and controls. There was a significant reduction in total cholesterol concentration in patients (Hedges' g = −0.19, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.06; P = 0.005).

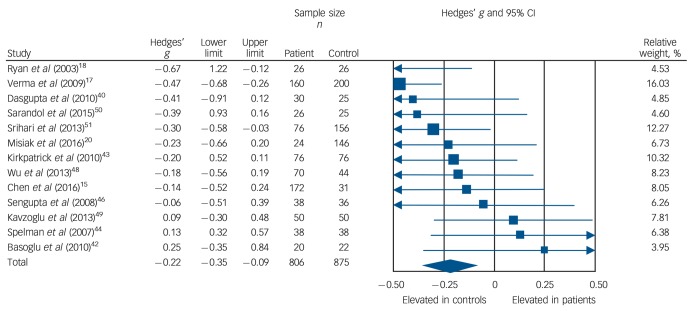

LDL cholesterol

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration was analysed using data from 13 studies, comprising 806 patients and 875 controls.15,17,18,20,40,42–44,46,48–51 Concentration was significantly decreased in patients compared with controls: g = −0.22, 95% CI −0.35 to −0.09; P = 0.001 (Fig. 3). This corresponds to an absolute decrease in LDL cholesterol of 0.15 mmol/L. There was no statistically significant between-sample heterogeneity (I2 = 29%; Q = 16.8, P = 0.16). Findings of Egger's test (P = 0.13) suggested that publication bias was not significant, and visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested symmetry (online Fig. DS4). Restricting analyses to ten BMI-matched studies demonstrated that LDL cholesterol remained significantly decreased in patients (n = 532) compared with controls (n = 481): g = −0.18, 95% CI −0.31 to −0.04; P = 0.012.15,18,20,40,42,43,46,48–50 Meta-regression of effect size for LDL cholesterol on absolute difference in BMI between patient and control groups (scatter plot shown in online Fig. DS9) revealed that BMI difference between the two cohorts was not a significant moderator of the LDL cholesterol effect size (β = −0.15, 95% CI −0.49 to 0.18; P = 0.38). There were insufficient studies to perform a sensitivity analysis where groups were matched for dietary intake. After restricting analyses to seven studies matched for ethnicity,15,17,18,40,44,46,51 we found LDL cholesterol remained significantly decreased in patients (n = 540) compared with controls (n = 512): g = −0.29, 95% CI −0.46 to −0.11; P < 0.01. After exclusion of two studies in which participants were not specifically documented as being physically healthy,17,51 LDL cholesterol remained significantly decreased in patients (n = 570) compared with controls (n = 519): g = −0.15, 95% CI −0.28 to −0.02; P = 0.03. All studies involved in the LDL cholesterol analysis were matched for age and gender, so these sensitivity analyses were not required.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol concentration in patients with first-episode psychosis and controls. There was a significant reduction in LDL cholesterol concentration in patients (Hedges' g = −0.22, 95% CI −0.35 to −0.09; P = 0.001).

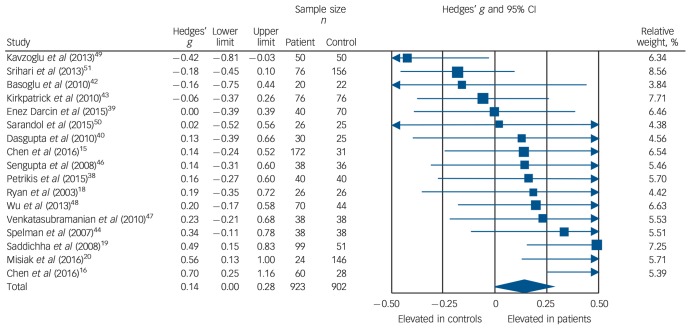

Triglycerides

Triglyceride concentration was analysed using data from 17 studies, comprising 923 patients and 902 controls.15,16,18–20,38–40,42–44,46–51 Concentration was significantly elevated in patients compared with controls: g = 0.14, 95% CI 0.00–0.28; P < 0.05 (Fig. 4). This corresponds to an absolute increase in triglyceride levels of 0.08 mmol/L. There was significant between-sample heterogeneity (I2 = 48%; Q = 30.6, P = 0.02). Findings of Egger's test (P = 0.28) suggested that publication bias was not significant, and visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested symmetry. After restricting analyses to 14 BMI-matched studies there was no longer a significant difference in triglyceride concentrations between patients (n = 710) and controls (n = 657): g = 0.13, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.27; P = 0.09.15,16,18,20,38–40,42,43,46–50 Meta-regression of effect size for triglycerides on absolute difference in BMI between patient and control groups (online Fig. DS10) revealed that BMI difference between the two cohorts was a significant moderator of the triglyceride effect size (β = 0.29, 95% CI 0.04–0.53; P = 0.024). After restricting analyses to three studies matched for dietary intake,18,19,40 triglyceride concentration remained significantly elevated in patients (n = 155) compared with controls (n = 102): g = 0.34, 95% CI 0.09–0.59; P < 0.01. Exclusion of one study that failed to match for gender revealed that triglyceride concentration remained significantly elevated in patients (n = 883) compared with controls (n = 832): g = 0.15, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.30; P < 0.05.39 After restricting analyses to six studies matched for ethnicity,15,18,40,44,46,51 there was no longer a significant difference in total cholesterol concentration between patients (n = 380) and controls (n = 312): g = 0.06, 95% CI −0.12 to 0.22; P = 0.49. After exclusion of one study in which participants were not specifically documented as being physically healthy,51 triglyceride concentration remained elevated in patients (n = 847) compared with controls (n = 746): g = 0.17, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.31; P = 0.02. All studies involved in the triglyceride analysis were matched for age so this sensitivity analysis was not required.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing triglyceride concentration in patients with first-episode psychosis and controls. There was an elevation in triglyceride concentration in patients (Hedges' g = 0.14, 95% CI 0.00–0.28; P < 0.05).

HDL cholesterol

High-density lipoprotein concentration was analysed using data from 16 studies, comprising 985 patients and 1036 controls.15,17–20,38–40,42–44,46,48–51 Concentrations were not altered in patients compared with controls: g = −0.19, 95% CI −0.39 to 0.02; P = 0.07 (online Fig. DS1). There was statistically significant between-sample heterogeneity (I2 = 77%; Q = 66.2, P < 0.01). Findings of Egger's test (P = 0.67) suggested that publication bias was not significant, and visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested symmetry – although we noted a single outlying study with a large standard error,42 probably the consequence of a small sample size. After analyses were restricted to 12 BMI-matched studies,15,18,20,38–40,42,43,46,48–50 no significant difference remained in HDL cholesterol concentration between patients (n = 612) and controls (n = 591): g = −0.23, 95% CI −0.53 to 0.06; P = 0.12. Meta-regression of effect size for HDL cholesterol on difference in BMI between patient and control groups (scatter plot shown in online Fig. DS11) revealed that BMI difference between the two cohorts was not a significant moderator of the HDL cholesterol effect size (β = −0.10, 95% CI −0.85 to 0.65; P = 0.79). After restricting analyses to three studies matched for dietary intake,18,19,40 no significant difference remained in HDL cholesterol concentration between patients (n = 155) and controls (n = 102): g = −0.04, 95% CI −0.28 to 0.782; P = 0.78. Exclusion of one study that failed to match for gender revealed that HDL cholesterol remained unaltered between patients (n = 945) and controls (n = 966): g = −0.16, 95% CI −0.37 to 0.05; P = 0.12.39 After restricting analyses to seven studies matched for ethnicity,15,17,18,40,44,46,51 no significant difference remained in HDL concentration between patients (n = 540) and controls (n = 512): g = −0.09, 95% CI −0.22 to 0.04; P = 0.16. After exclusion of two studies in which participants were not specifically documented as being physically healthy,17,51 HDL cholesterol levels remained unaltered between patients (n = 749) and controls (n = 680): g = −0.21, 95% CI −0.46 to 0.04; P = 0.10. All studies involved in HDL cholesterol analysis were matched for age so this sensitivity analysis was not performed.

Leptin

Leptin concentration in patients and controls was analysed using data from five studies, comprising 162 patients and 164 controls.41,42,44,45,47 Leptin concentration was not altered in patients compared with controls: g = 0.05, 95% CI −0.31 to 0.42; P = 0.78 (online Fig. DS2). Between-sample heterogeneity was medium (I2 = 59%; Q = 12.3, P = 0.03). Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested asymmetry, although this interpretation should be taken with caution in the context of the small number of studies, and the single study driving asymmetry exhibiting a large standard error,45 probably the consequence of small sample size (n = 7). Egger's test of the intercept was not possible owing to the small number of studies. After restricting analyses to BMI-matched studies,41,42,45,47 there remained no significant difference in leptin concentration between patients (n = 124) and controls (n = 126): g = −0.07, 95% CI −0.32 to 0.17; P = 0.56. All studies involved in leptin analysis matched for age so this sensitivity analysis was not required. Exclusion of one study that failed to match for age revealed that leptin concentration remained unaltered between patients (n = 112) and controls (n = 114): g = 0.14, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.63; P = 0.57.41 There were insufficient studies to perform sensitivity analyses where groups were matched for dietary intake or ethnicity.

Discussion

The main findings of this meta-analysis are that first-episode psychosis is associated with decreased total and LDL cholesterol levels but increased triglyceride levels compared with healthy control groups, with no difference in HDL cholesterol or leptin levels. The absolute difference in lipid parameters demonstrated in FEP compared with controls was a decrease in total cholesterol of 0.26 mmol/L (upper limit for total cholesterol levels in adults 5.00 mmol/L),52 a decrease in LDL cholesterol of 0.15 mmol/L (upper limit for LDL cholesterol levels in adults 3.00 mmol/L),52 and an increase in triglycerides of 0.08 mmol/L (upper limit for triglyceride levels in adults 1.70 mmol/L).52 Data from studies focusing on the efficacy of statin therapy in individuals at low risk of cardiovascular disease demonstrate that an absolute reduction in LDL cholesterol of 1 mmol/L is associated with a relative risk reduction of major vascular events of 21%,53 so a reduction in LDL cholesterol of 0.15 mmol/L seen in FEP may be associated with an approximate 3% risk reduction in cardiovascular disease. Total and LDL cholesterol findings remained significant in the sensitivity analyses, except for the one for ethnicity, where total cholesterol difference was no longer significant. Specifically, total and LDL cholesterol findings remained significant in BMI-matched analyses, and meta-regression revealed that BMI difference between the two cohorts was not a significant moderator for either finding. The triglyceride findings were no longer significant in sensitivity analyses that matched for BMI and ethnicity, and meta-regression revealed that BMI difference between the two cohorts was a significant moderator. Leptin concentrations were not altered in patients relative to controls, although this result should be interpreted with caution owing to the small sample size used in this analysis.

Our findings extend the meta-analysis by Perry et al,21 by using a larger sample (2351 participants compared with 1137 in Perry's paper) and including additional lipidomic measures and sensitivity analyses. Our finding of reduced total cholesterol is consistent with their finding, but in addition we show a significant reduction in LDL cholesterol and increase in triglyceride levels, which Perry et al did not find, potentially because of lack of power in their study. Our findings contrast with evidence of elevated total and LDL cholesterol in chronic schizophrenia.14 Our findings also contrast with recent evidence of broader metabolic dysfunction in FEP, specifically glucose dysregulation.21,25,54 However, our demonstration of raised triglyceride concentrations in FEP is compatible with the notion of FEP being associated with impairments in glucose homeostasis, with hypertriglyceridaemia recognised as accompanying development of type 2 diabetes mellitus.55 Indeed, in apparently healthy men aged 26–45 years the hazard ratio for developing type 2 diabetes in those with high triglyceride levels (1.85–3.38 mmol/L) compared with low triglyceride levels (0.34–0.75 mmol/L) is 2.11.56

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this analysis include the focus on patients with FEP and minimal or no antipsychotic exposure, thus limiting the duration of secondary illness-related factors that may result in dyslipidaemia. Nevertheless, population studies and meta-analyses have previously demonstrated that individuals with FEP already have poorer dietary habits, decreased physical activity and an increased likelihood of smoking compared with age-matched controls.57–60 In line with clinical practice,29 our definition of FEP included patients with several years of illness, and duration of untreated psychosis was not documented in all studies; thus there were insufficient studies to perform meta-regression analyses examining the impact of illness duration. Therefore, some patients might already have been exposed to lifestyle risk factors for some time. However, prolonged duration of poor lifestyle habits would not be expected to result in the total and LDL cholesterol reductions we observed. Similarly, the limitation that a third of the analysed patient cohort had been prescribed up to 14 days of antipsychotic medication might be expected to be associated with increased total and LDL cholesterol levels. This suggests that the reductions in cholesterol levels observed might be larger when the impact of poor lifestyle habits and medication are controlled for. Matching for diet was performed in only three studies,18,19,40 and a sensitivity analysis examining dietary impact could be performed only for triglycerides (which maintained significance for raised triglyceride levels in patients compared with controls). Similarly, only two studies matched for the amount of regular exercise taken by participants.18,19 High fat intake and obesity are the most common causes of dyslipidaemia.36 Exercise is associated with reduced lipid levels, potentially through enhancing skeletal muscle lipid metabolism preferentially over glycogen.61 We cannot therefore exclude dietary or exercise differences as contributing to our findings, although poor lifestyle factors would be expected to oppose the effects we observed, not inflate them. Moreover, overmatching of patients and controls for lifestyle factors could result in samples poorly representative of populations. Data from large-scale, population-based studies and registries have established that plasma lipids and lipoproteins change modestly 1–6 h following habitual food intake (compared with fasting levels, non-fasting triglyceride levels increase by up to 0.3 mmol/L and non-fasting total and LDL cholesterol levels decrease by up to 0.2 mmol/L, probably owing to haemodilution due to fluid intake with a meal).62 In view of this we extracted study information regarding duration of fasting (online Table DS10). Sensitivity analyses excluding studies with unclear fasting duration showed that the findings of reduced total and LDL cholesterol levels in FEP compared with controls remained significant,16,19,41,43,45,50 and also confirmed the findings of no significant difference in HDL cholesterol or leptin levels between patients and controls. However, triglyceride levels were no longer elevated in patients compared with controls (results in online supplement DS1). Notwithstanding these analyses, we cannot exclude the possibility that the patients were less compliant with the fast. This warrants further investigation in future studies.

Another potential limitation of the meta-analysis is the inclusion of participants who might not have been representative of FEP and control populations in general. However, all studies included in the meta-analysis used DSM-IV criteria for selection of patients, and all studies were deemed to be adequate for case selection as part of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale quality assessment (online Table DS10). We can therefore be confident that the sampled patient group was adequately representative of the patient population. However, we note that eight studies used hospital and university staff or relatives of staff as controls;17,18,38,39,41,46,48,50 these individuals may be poorly representative of the socioeconomic background of population controls. However, higher socioeconomic status is associated with reduced cardiovascular risk, for example total cholesterol is inversely associated with educational level.63 This would therefore not explain our findings of reduced total and LDL cholesterol in FEP. Four studies failed to detail how controls were recruited;16,20,47,49 however, sensitivity analyses excluding these four studies did not alter results (online supplement DS1).

Sensitivity analyses that matched for ethnicity resulted in a loss of significance for both total cholesterol and triglyceride findings, which may point to ethnic differences between patients and controls contributing to results. Moreover, a BMI-matched sensitivity analysis for triglycerides resulted in loss of significance for the finding of raised triglycerides in FEP, and meta-regression revealed that BMI difference between patient and control groups was a significant moderator of the triglyceride effect size. Obesity is a major cause of dyslipidaemia and lipid levels are directly related to BMI.36 Thus, group differences in BMI could have contributed to observed triglyceride differences, although overall patient groups had lower BMI levels compared with controls (average difference 0.39 kg/m2). However, BMI-matched sensitivity analyses for total and LDL cholesterol remained significant, and meta-regression demonstrated that BMI difference between the two groups did not moderate observed effect sizes. Moreover, poor lifestyle habits in the patient cohort would be expected to increase total and LDL cholesterol levels, thus are unlikely to explain the reduction in cholesterol parameters we observed.

Although participants in the meta-analysis were described as physically healthy with no illness that would affect lipid parameters, only seven studies referred to the use of over-the-counter medication as a specific exclusion criterion,18,38–41,43,44 and only six studies defined psychotropic use other than antipsychotics as an exclusion criterion;16,40–43,47 see online Table DS9. Thus, the potential use of psychiatric medication other than antipsychotics that might increase lipid parameters, such as mood stabilisers,57 or lipid-lowering medication is a potential confounding factor for some of the studies that we were unable to account for fully. However, evidence in chronic schizophrenia indicates that patients are less likely to receive lipid-lowering drugs than the general population,64 so this is unlikely to account for the reductions we see. Although no study included in our analysis specifically excluded participants based on a historical diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, all but two studies included statements that described participants as physically healthy (Table DS9).17,65 Like the process of BMI-matching patients and controls, this preferential selection of physically healthy participants may have excluded participants truly representative of the patient (and control) cohort, with overmatching of groups.

Our database search strategy was complemented by hand-searching, which identified additional studies that were included in the final analysis. This could indicate that there are other studies missed by the database search; however, as we hand-searched the reference lists of the studies included and additional review articles, any missing articles have eluded the field in general.

We observed relatively high heterogeneity in some of our analyses, notably of triglycerides. The use of plasma or serum sampling for lipid parameters, which has been reported to result in a 3–5% variation in cholesterol measures,66,67 and differences in sample inclusion criteria may account for some of this heterogeneity. In addition, six studies failed to document the model or brand of analyser used (online Table DS10), thereby precluding confirmation of interassay reliability.19,39,43,44,46,51 Nevertheless, the random effects model we used is robust to heterogeneity and subgroup analyses explored potential sources of heterogeneity. It is important to note that because most studies in our analysis selected patients who were physically healthy, and matched for a number of risk factors for dyslipidaemia such as BMI, our findings should not be extended to patients with these risk factors. By the same token, our meta-analysis should not be extended to draw conclusions on rates of categorical diagnoses of dyslipidaemia in FEP. The data in our analyses are cross-sectional and future longitudinal research is required to disentangle the relationships we observed and the potential role of modifiable factors.

Future directions

Although the effect sizes observed in our meta-analysis are modest, they are striking in the context of the opposite findings in patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Our findings indicate that psychotic disorders are not associated with an intrinsic elevation in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol or reduction in HDL cholesterol, and indicate that patients have favourable profiles of these lipids early in their illness. Our results contrast with the findings of meta-analyses in patients with chronic disorder, which, in comparison with the general population, show increased risk of the metabolic syndrome and hypercholesterolaemia.14 Taken together with these, our findings suggest that the increased risk of hypercholesterolaemia in psychotic illness is a consequence of potentially modifiable factors associated with chronic psychotic illness. Whether lower cholesterol in FEP is indicative of inherent cardiometabolic differences between FEP and controls, as suggested by recent meta-analytic evidence of glucose dysregulation in early psychosis,21,54,68 remains to be determined. Recent Genome Wide Association Study evidence has demonstrated pleiotropic enrichment between genetic polymorphisms associated with both schizophrenia and cardiovascular disease, and lipid disorder69 This could suggest there are common molecular pathways underlying both psychosis and metabolic dysregulation.70 Adipocytokine disturbances are one possibility: there is robust evidence of immune dysregulation in antipsychotic-naïve FEP, with elevated peripheral cytokines that include the adipocytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).71 Interleukin-6 has been demonstrated to reduce lipid levels in animal models.72 Active, untreated rheumatoid arthritis, which is associated with elevated IL-6 and TNF-α levels, is associated with decreased total and LDL cholesterol levels,73 and these increase with IL-6 and TNF-α monoclonal blockade.74 Thus, by extension, inflammation could be a mechanism underlying the lipid alterations we found. There were insufficient data for us to test the hypothesis of broader adipocytokine dysregulation in FEP further, and our leptin analysis demonstrated no difference between patients and controls. Further preclinical and clinical studies are required to probe this potential association.

A message for clinicians is that the secondary, potentially modifiable risk factors should be considered and addressed from onset of illness before dyslipidaemia has developed. Potential modifiable factors associated with schizophrenia include poor nutrition,75 sedentary behaviour,76 alcohol and substance misuse,77 poorer access to healthcare,78 and long-term antipsychotic treatment.11,79 Among these, antipsychotics – especially the newer antipsychotics – are well recognised as potentially modifiable risk factors for metabolic dysfunction.80–82 The mechanisms by which antipsychotics contribute to lipid disorder remain poorly understood, but may result from weight gain secondary to activity at 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) 5-HT2 and 5-HT1 receptors, leading to increased dietary fat intake.83,84 It is recognised that individuals with FEP and a relatively lower BMI tend to gain weight rapidly when treated with an antipsychotic associated with a high weight gain potential.85 Longitudinal studies examining changes in lipids from the at-risk mental state and over the course of the first episode and first few years of illness would be useful to determine what underlies the transition from low cholesterol and LDL levels to elevated levels. Such research should consider the relative role of modifiable risk factors such as nutrition, physical activity and antipsychotic medication on lipid changes. We also demonstrated the paucity of studies examining adipocytokine parameters in early schizophrenia. This indicates that more research is required to examine the potential mechanisms underlying the lipid profile we have identified in this meta-analysis.

Our finding of increased triglyceride concentrations in FEP is consistent with meta-analytic evidence of raised triglyceride levels in patients with chronic illness compared with the general population.14 Elevated triglyceride levels are considered a marker of insulin resistance, and predict risk for impaired fasting glucose concentration.56 As such, triglycerides are used in diabetes risk prediction models.86–88 The proposed mechanism sees insulin resistance at the level of the adipocyte associated with increased intracellular hydrolysis of triglycerides and release of fatty acids into the circulation.89 This induces hepatic production and release of very low-density lipoproteins, which results in hypertriglyceridaemia.89 Thus, raised triglyceride concentrations in FEP may reflect early glucose dysregulation and insulin resistance, consistent with recent meta-analyses indicating that patients with FEP show altered glucose homeostasis.21,25,54 Given that they are indicators of early glucoregulatory dysfunction, triglycerides could be a focus for early intervention to prevent the development of diabetes in schizophrenia.

Implications

Our data suggest that total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein levels are reduced early in the course of schizophrenia, indicating that the hypercholesterolaemia seen in chronic disorder is secondary and potentially modifiable. In contrast, our finding of elevated triglyceride levels early in the course of schizophrenia is a metabolic indicator of an increased risk of diabetes. In terms of translation to the clinical domain, these findings suggest that prevention of dyslipidaemia and diabetes needs to be prioritised from onset of psychosis, with the adoption of early lifestyle interventions and careful antipsychotic prescribing which considers both benefits and risks.90

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Venkatasubramanian of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuroscience, Bengaluru, India, Dr Vivek Phutane of the Yale University School of Medicine and Connecticut Mental Health Center, USA, and Dr Blazej Misiak of the Wroclaw Medical University, Poland, for providing additional data.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

O.D.H. has received investigator-initiated research funding from and/or participated in advisory/ speaker meetings organised by Astra-Zeneca, Autifony, BMS, Eli Lilly, Heptares, Janssen, Lundbeck, Lyden-Delta, Otsuka, Servier, Sunovion, Rand and Roche.

Funding

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council, the Maudsley Charity, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

References

- 1. Beary M, Hodgson R, Wildgust HJ. A critical review of major mortality risk factors for all-cause mortality in first-episode schizophrenia: clinical and research implications. J Psychopharmacol 2012; 26: 52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 2013; 170: 324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoang U, Goldacre MJ, Stewart R. Avoidable mortality in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in England. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2013; 127: 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2014; 10: 425–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, Inskip H. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 196: 116–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Osby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm county, Sweden. Schizophr Res 2000; 45: 21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive Summary of the Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001; 285: 2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grundy SM, Cieeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute scientific statement. Circulation 2005; 112: 2735–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J, IDF Epidemiology Task Force consensus Group The metabolic syndrome – a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005; 366: 1059–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1: Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. WHO, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malhotra N, Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Kulhara P. Metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia. Indian J Psychol Med 2013; 35: 227–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papanastasiou E. The prevalence and mechanisms of metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia: a review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol 2013; 3: 33–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, De Hert M, Wampers M, Ward PB, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2015; 14: 339–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vancampfort D, Wampers M, Mitchell AJ, Correll CU, De Herdt A, Probst M, et al. A meta-analysis of cardio-metabolic abnormalities in drug naive, first-episode and multi-episode patients with schizophrenia versus general population controls. World Psychiatry 2013; 12: 240–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen DC, Du XD, Yin GZ, Yang KB, Nie Y, Wang N, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia: relationships with clinical phenotypes and cognitive deficits. Psychol Med 2016; 46: 3219–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen S, Broqueres-You D, Yang G, Wang Z, Li Y, Yang F, et al. Male sex may be associated with higher metabolic risk in first-episode schizophrenia patients: a preliminary study. Asian J Psychiatr 2016; 21: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Verma SK, Subramaniam M, Liew A, Poon LY. Metabolic risk factors in drug-naive patients with first-episode psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70: 997–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ryan MC, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired fasting glucose tolerance in first-episode, drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saddichha S, Manjunatha N, Ameen S, Akhtar S. Metabolic syndrome in first episode schizophrenia – a randomized double-blind controlled, short-term prospective study. Schizophr Res 2008; 101: 266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Misiak B, Laczmanski L, Sloka NK, Szmida E, Piotrowski P, Loska O, et al. Metabolic dysregulation in first-episode schizophrenia patients with respect to genetic variation in one-carbon metabolism. Psychiatry Res 2016; 238: 607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perry BI, McIntosh G, Weich S, Singh S, Rees K. The association between first-episode psychosis and abnormal glycaemic control: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3: 1049–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: 1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000; 283: 2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gurillo P, Jauhar S, Murray RM, MacCabe JH. Does tobacco use cause psychosis? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2015; 2: 718–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, Donocik JG, Jauhar S, Howes OD. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74: 261–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, De Herdt A, Yu W, De Hert M. Is the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities increased in early schizophrenia? A comparative meta-analysis of first episode, untreated and treated patients. Schizophr Bull 2013; 39: 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, Stein K, Driesen N, Corcoran CM, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q 1999; 70: 273–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell'Olio M, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2005; 39: 964–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Breitborde NJ, Srihari VH, Woods SW. Review of the operational definition for first-episode psychosis. Early interv Psychiatry 2009; 3: 259–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010; 25: 603–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kratz A, Lewandrowski KB. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital, weekly clinicopathological exercises. Normal reference laboratory values. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1063–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bowden J, Tierney JF, Copas AJ, Burdett S. Quantifying, displaying and accounting for heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of RCTs using standard and generalised Q statistics. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011; 11: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Egger M, Zellweger-Zahner T, Schneider M, Junker C, Lengeler C, Antes G. Language bias in randomised controlled trials published in English and German. Lancet 1997; 350: 326–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of interventions. Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Durrington P. Dyslipidaemia. Lancet 2003; 362: 717–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 131: e29–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Petrikis P, Tigas S, Tzallas AT, Papadopoulos I, Skapinakis P, Mavreas V. Parameters of glucose and lipid metabolism at the fasted state in drug-naive first-episode patients with psychosis: evidence for insulin resistance. Psychiatry Res 2015; 229: 901–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Enez Darcin A, Yalcin Cavus S, Dilbaz N, Kaya H, Dogan E. Metabolic syndrome in drug-naive and drug-free patients with schizophrenia and in their siblings. Schizophr Res 2015; 166: 201–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dasgupta A, Singh OP, Rout JK, Saha T, Mandal S. Insulin resistance and metabolic profile in antipsychotic naive schizophrenia patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2010; 34: 1202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Arranz B, Rosel P, Ramirez N, Duenas R, Fernandez P, Sanchez JM, et al. Insulin resistance and increased leptin concentrations in noncompliant schizophrenia patients but not in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65: 1335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Basoglu C, Oner O, Gunes C, Semiz UB, Ates AM, Algul A, et al. Plasma orexin A, ghrelin, cholecystokinin, visfatin, leptin and agouti-related protein levels during 6-week olanzapine treatment in first-episode male patients with psychosis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2010; 25: 165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kirkpatrick B, Garcia-Rizo C, Tang K, Fernandez-Egea E, Bernardo M. Cholesterol and triglycerides in antipsychotic-naive patients with nonaffective psychosis. Psychiatry Res 2010; 178: 559–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spelman LM, Walsh PI, Sharifi N, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired glucose tolerance in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Diabet Med 2007; 24: 481–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang HC, Yang YK, Chen PS, Lee IH, Yeh TL, Lu RB. Increased plasma leptin in antipsychotic-naive females with schizophrenia, but not in males. Neuropsychobioiogy 2007; 56: 213–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sengupta S, Parrilla-Escobar MA, Klink R, Fathalli F, Ying Kin N, stip E, et al. Are metabolic indices different between drug-naive first-episode psychosis patients and healthy controls? Schizophr Res 2008; 102: 329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Venkatasubramanian G, Chittiprol S, Neelakantachar N, Shetty TK, Gangadhar BN. A longitudinal study on the impact of antipsychotic treatment on serum leptin in schizophrenia. Clin Neuropharmacol 2010; 33: 288–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu X, Huang Z, Wu R, Zhong Z, Wei Q, Wang H, et al. The comparison of glycometabolism parameters and lipid profiles between drug-naive, first-episode schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophr Res 2013; 150: 157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kavzoglu SO, Hariri AG. Intracellular Adhesion Molecule (ICAM-1), Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule (VCAM-1) and E-selectin levels in first episode schizophrenic patients. Klin Psikofarmakol B 2013; 23: 205–14. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sarandol A, Sarandol E, Acikgoz HE, Eker SS, Akkaya C, Dirican M. First-episode psychosis is associated with oxidative stress: effects of short-term antipsychotic treatment. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2015; 69: 699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Srihari VH, Phutane VH, Ozkan B, Chwastiak L, Ratliff JC, Woods SW, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenia: defining a critical period for prevention. Schizophr Res 2013; 146: 64–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, et al. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). The Fifth Joint Task Force of the European society of Cardiology and Other societies on cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1635–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaboration, Mihaylova B Emberson J Blackwell L Keech A Simes J et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2012; 380: 581–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Greenhalgh AM, Gonzalez-Bianco L, Garcia-Rizo C, Fernandez-Egea E, Miller B, Arroyo MB, et al. Meta-analysis of glucose tolerance, insulin, and insulin resistance in antipsychotic-naive patients with nonaffective psychosis. Schizophr Res 2017; 179: 57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lin SX, Berlin I, Younge R, Jin Z, Sibley CT, Schreiner P, et al. Does elevated plasma triglyceride level independently predict impaired fasting glucose?: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 342–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tirosh A, Shai I, Bitzur R, Kochba I, Tekes-Manova D, Israeli E, et al. Changes in triglyceride levels over time and risk of type 2 diabetes in young men. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 2032–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stubbs B, Firth J, Berry A, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Gaughran F, et al. How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. schizophr Res 2016; 176: 431–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Juutinen J, Hakko H, Meyer-Rochow VB, Rasanen P, Timonen M, Study-70 Research Group Body mass index (BMI) of drug-naive psychotic adolescents based on a population of adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Eur Psychiatry 2008; 23: 521–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Koivukangas J, Tammelin T, Kaakinen M, Maki P, Moilanen I, Taanila A, et al. Physical activity and fitness in adolescents at risk for psychosis within the Northern Finland 1986 Birth Cohort. Schizophr Res 2010; 116: 152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Myles N, Newall H, Compton MT, Curtis J, Nielssen O, Large M. The age at onset of psychosis and tobacco use: a systematic meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012; 47: 1243–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Earnest CP, Artero EG, Sui X, Lee DC, Church TS, Blair SN. Maximal estimated cardiorespiratory fitness, cardiometabolic risk factors, and metabolic syndrome in the aerobics center longitudinal study. Mayo Clin Proc 2013; 88: 259–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Langsted A, Freiberg JJ, Nordestgaard BG. Fasting and nonfasting lipid levels: influence of normal food intake on lipids, lipoproteins, apolipoproteins, and cardiovascular risk prediction. Circulation 2008; 118: 2047–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Benetou V, Chloptsios Y, Zavitsanos X, Karalis D, Naska A, Trichopoulou A. Total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol in relation to socioeconomic status in a sample of 11,645 Greek adults: the EPIC study in Greece. European Prospective investigation into Nutrition and Cancer, scand J Public Health 2000; 28: 260–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, McEvoy JP, Davis SM, Stroup TS, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res 2006; 86: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Phutane VH, Tek C, Chwastiak L, Ratliff JC, Ozyuksel B, Woods SW, et al. Cardiovascular risk in a first-episode psychosis sample: a ‘critical period’ for prevention? Schizophr Res 2011; 127: 257–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations in serum/plasma pairs. Clin Chem 1977; 23: 60–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cloey T, Bachorik PS, Becker D, Finney C, Lowry D, Sigmund W. Reevaluation of serum-plasma differences in total cholesterol concentration. JAMA 1990; 263: 2788–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, Donocik JG, Jauhar S, Howes OD. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74: 261–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Andreassen OA, Djurovic S, Thompson WK, Schork AJ, Kendler KS, O'Donovan MC, et al. Improved detection of common variants associated with schizophrenia by leveraging pleiotropy with cardiovascular-disease risk factors. Am J Hum Genet 2013; 92: 197–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Liu Y, Li Z, Zhang M, Deng Y, Yi Z, Shi T. Exploring the pathogenetic association between schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus diseases based on pathway analysis. BMC Med Genomics 2013; 6 (suppl 1): S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Upthegrove R, Manzanares-Teson N, Barnes NM. Cytokine function in medication-naive first episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 2014; 155: 101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Katsume A, Saito H, Yamada Y, Yorozu K, Ueda O, Akamatsu K, et al. Anti-interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor antibody suppresses Castleman's disease like symptoms emerged in IL-6 transgenic mice. Cytokine 2002; 20: 304–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Fitz-Gibbon PD, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Total cholesterol and LDL levels decrease before rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69: 1310–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody – a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 1761–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dipasquale S, Pariante CM, Dazzan P, Aguglia E, McGuire P, Mondelli V. The dietary pattern of patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res 2013; 47: 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stubbs B, Gardner-Sood P, Smith S, Ismail K, Greenwood K, Farmer R, et al. Sedentary behaviour is associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in people with psychosis. Schizophr Res 2015; 168: 461–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Koola MM, McMahon RP, Wehring HJ, Liu F, Mackowick KM, Warren KR, et al. Alcohol and cannabis use and mortality in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. J Psychiatr Res 2012; 46: 987–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kurdyak P, Vigod S, Calzavara A, Wodchis WP. High mortality and low access to care following incident acute myocardial infarction in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2012; 142: 52–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Galling B, Roldan A, Nielsen RE, Nielsen J, Gerhard T, Carbon M, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in youth exposed to antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73: 247–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, Yu W, Correll CU. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011; 8: 114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Heal DJ, Gosden J, Jackson HC, Cheetham SC, Smith SL. Metabolic consequences of antipsychotic therapy: preclinical and clinical perspectives on diabetes, diabetic ketoacidosis, and obesity. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2012; 212: 135–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Howes OD, Bhatnagar A, Gaughran FP, Amiel SA, Murray RM, Pilowsky LS. A prospective study of impairment in glucose control caused by clozapine without changes in insulin resistance. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 361–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Reynolds GP, Zhang ZJ, Zhang XB. Association of antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain with a 5-HT2C receptor gene polymorphism. Lancet 2002; 359: 2086–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kim SF, Huang AS, Snowman AM, Teuscher C, Snyder SH. From the Cover: Antipsychotic drug-induced weight gain mediated by histamine H1 receptor-linked activation of hypothalamic AMP-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 3456–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kinon BJ, Kaiser CJ, Ahmed S, Rotelli MD, Kollack-Walker S. Association between early and rapid weight gain and change in weight over one year of olanzapine therapy in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 25: 255–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Stern MP, Fatehi P, Williams K, Haffner SM. Predicting future cardiovascular disease: do we need the oral glucose tolerance test? Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 1851–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wilson PW, Meigs JB, Sullivan L, Fox CS, Nathan DM, D'Agostino RB. Prediction of incident diabetes mellitus in middle-aged adults: the Framingham Offspring study. Arch intern Med 2007; 167: 1068–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Bang H, Pankow JS, Ballantyne CM, Golden SH, et al. Identifying individuals at high risk for diabetes: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 2013–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ginsberg HN. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin invest 2000; 106: 453–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Cooper SJ, Reynolds GP, Barnes T, England E, Haddad PM, et al. BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol 2016; 30: 717–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]