Abstract

Previous research has evaluated antibody responses toward an influenza virus vaccine in the context of deficiencies for vitamins A and D (VAD+VDD). Results showed that antibodies and antibody-forming cells in the respiratory tract were reduced in VAD+VDD mice. However, effectors were recovered when oral supplements of vitamins A + D were delivered at the time of vaccination. Here we address the question of how vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell responses are affected by deficiencies for vitamins A + D. VAD+VDD and control mice were vaccinated with an intranasal, cold-adapted influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 vaccine, with or without oral supplements of vitamins A + D. Results showed that the percentages of vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell and total CD4+ T cell responses were low among lymphocytes in the airways of VAD+VDD animals compared to controls. The CD103 membrane marker, a protein that binds e-cadherin (expressed on respiratory tract epithelial cells), was unusually high on virus-specific T cells in VAD+VDD mice compared to controls. Interestingly, when T cells specific for the PA224–233/Db epitope were compared with T cells specific for the NP366–374/Db epitope, the former population was more strongly positive for CD103. Preliminary experiments revealed normal or above-normal percentages for vaccine-induced T cells in airways when VAD+VDD animals were supplemented with vitamins A + D at the time of vaccination and on days 3 and 7 after vaccination. Our results suggest that close attention should be paid to levels of vitamins A and D among vaccine recipients in the clinical arena, as low vitamin levels may render individuals poorly responsive to vaccines.

Keywords: : vitamin deficiency, vaccine-induced T cells, influenza virus, bronchoalveolar lavage, vitamins A and D

Introduction

Vitamins A and D each influence a plethora of immune functions (25). Their receptors (e.g., RAR-RXR for vitamin A and VDR-RXR for vitamin D) can serve as signaling molecules, but are best known for their functions as transcription factors. Receptors for vitamins A and D each bind canonical sequence motifs within mammalian DNA, usually comprising two closely situated 6-nucleotide ½ sites. However, interactions between receptors and their DNA targets can be promiscuous. Motifs need not be exact, and ½ sites are in some cases separated by long distances. Cross-regulation between vitamin A and vitamin D receptors (and other related nuclear hormone receptors such as the thyroid hormone receptor) is common and can be either synergistic or competitive depending on the nuclear environment of the responding cell (4–6,15,20–23,25).

Previous studies showed that when mice were vitamin A deficient and vitamin D deficient (VAD+VDD), they exhibited impaired antibody responses toward an influenza virus vaccine. When these VAD+VDD mice were supplemented with vitamins A + D at the time of vaccination, their responses were improved (33). Here we describe an evaluation of T cell responses after intranasal influenza virus vaccination in the context of VAD+VDD, with or without vitamin supplementation.

Materials and Methods

Animal model

Animal care practices followed the Association for Assessment and Accreditation for Laboratory Animal Care guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To establish VAD+VDD mice, pregnant female C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice (days 4–5 gestation) from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) were placed on a characterized diet (Cat#TD.10616; Harlan Laboratories, Madison, WI) in filter-top cages in a Biosafety Level 2+ containment area. Control mice received the base diet, but with vitamin A palmitate added at 15 IU/g and vitamin D added at 1.5 IU/g (Harlan TD.10764). Cages of VAD+VDD animals were placed in dedicated cubicles with light emitting diode bulbs as the source of light to avoid UV-B irradiation. Pregnant females were maintained on diets throughout their pregnancies, and weaned pups were maintained on diets throughout maturation and experimentation. To confirm vitamin deficiencies, sera were spot checked as described previously (33).

Adult mice >6 weeks were used for experimentation. All experiments were repeated to ensure reproducibility, unless stated otherwise. Mice were anesthetized with avertin and administered 30 μL of a cold-adapted derivative of A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8, kindly provided by Dr. J. McCullers) by the intranasal route (18,19). The virus had been amplified in hens' eggs at 33°C. Vaccine was at a concentration of 1.25 × 109 EID50/mL. Groups of vaccinated, VAD+VDD mice received no vitamin supplement or a vitamin supplement comprising 600 IU retinyl palmitate (Nutrisorb A; Interplexus, Inc., Kent, WA) and/or 40 IU vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol, Pure encapsulations, Sudbury, MA). Dosing was by oral gavage on days 0, 3, and 7 relative to vaccination. Ten days after vaccination, mice were tested for virus-specific T cells in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids, nasal tissues, or lungs. In one experiment, splenocytes were examined from naive animals.

Cell collection, staining, and T cell analyses by flow cytometry

Mice were sacrificed on day 10 after vaccination and BAL was collected by inserting catheters into trachea and washing three times with 1 mL PBS. Nasal tissues were prepared by discarding skin, lower jaws, soft palates, muscles, cheek bones, and incisors from heads. Remaining nasal tissues were digested with collagenase and cells were purified on percoll gradients as described previously (28). Lungs were also digested with collagenase, and gradient purified. Spleens were prepared from naive animals by cell separation and straining through a 70 μM cell strainer; red blood cells were lysed with Red Cell Lysis Buffer (Stem Cell). MHC class I tetramers were generated by folding peptides with heavy and light chains as described previously (1,8,26). Staining of cells with tetramer reagents (PE or APC conjugated) was for 1 h at room temperature. Additional staining was for 15–20 min on ice in microtiter plates with antibodies, including anti-CD8 (Cat#551162, PerCP Cy5.5 conjugate; BD Biosciences, previously named BD Pharmingen), anti-CD4 (Cat#17-0041-83, APC conjugate, eBioscience or Cat# 553730, PE conjugate; BD Pharmingen), anti-CD103 (Cat#557494, FITC conjugate; BD Biosciences), anti-CD11a (Cat# 553340, FITC-conjugate; BD Biosciences), anti-CD3 (Cat#553066, APC conjugate; BD Biosciences), and anti-CD44 (Cat#559250, APC conjugate or Cat#553141, PE conjugate; BD Biosciences). Washes were with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 1% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 0.01 g/L sodium azide. Splenocytes were resuspended in 100 μL 1:1,000 7AAD (Invitrogen) in PBS after staining, so that dead cells could be excluded from flow cytometric analyses. Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur or an LSR Fortessa X-20 (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using Flowjo Software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR) or FCS Express 6.0 Software. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism Software using unpaired t tests to evaluate cellular frequencies from individually tested mice. For the purpose of statistical analyses of CD103Hi cell percentages among NP366–374/Db-specific and PA224–233/Db-specific T cells populations, samples with fewer than 100 evaluable, tetramer-positive cells were excluded.

Results and Discussion

Vaccine-specific T cell responses in the airways of VAD+VDD mice

Experiments were designed to examine virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses in the lower airway after intranasal vaccination of vitamin-deficient mice with a cold-adapted PR8-based influenza virus vaccine. To conduct this study, we focused on immunodominant responses to NP366–374/Db and PA224–233/Db epitopes (10). Cells responsive to these epitopes are present in the BAL on day 10 after vaccination in wild-type mice, and are easily identified by tetramer staining. We conducted four separate experiments. In two cases, samples were pooled from each test group before analyses, and in two cases, each mouse sample was tested individually.

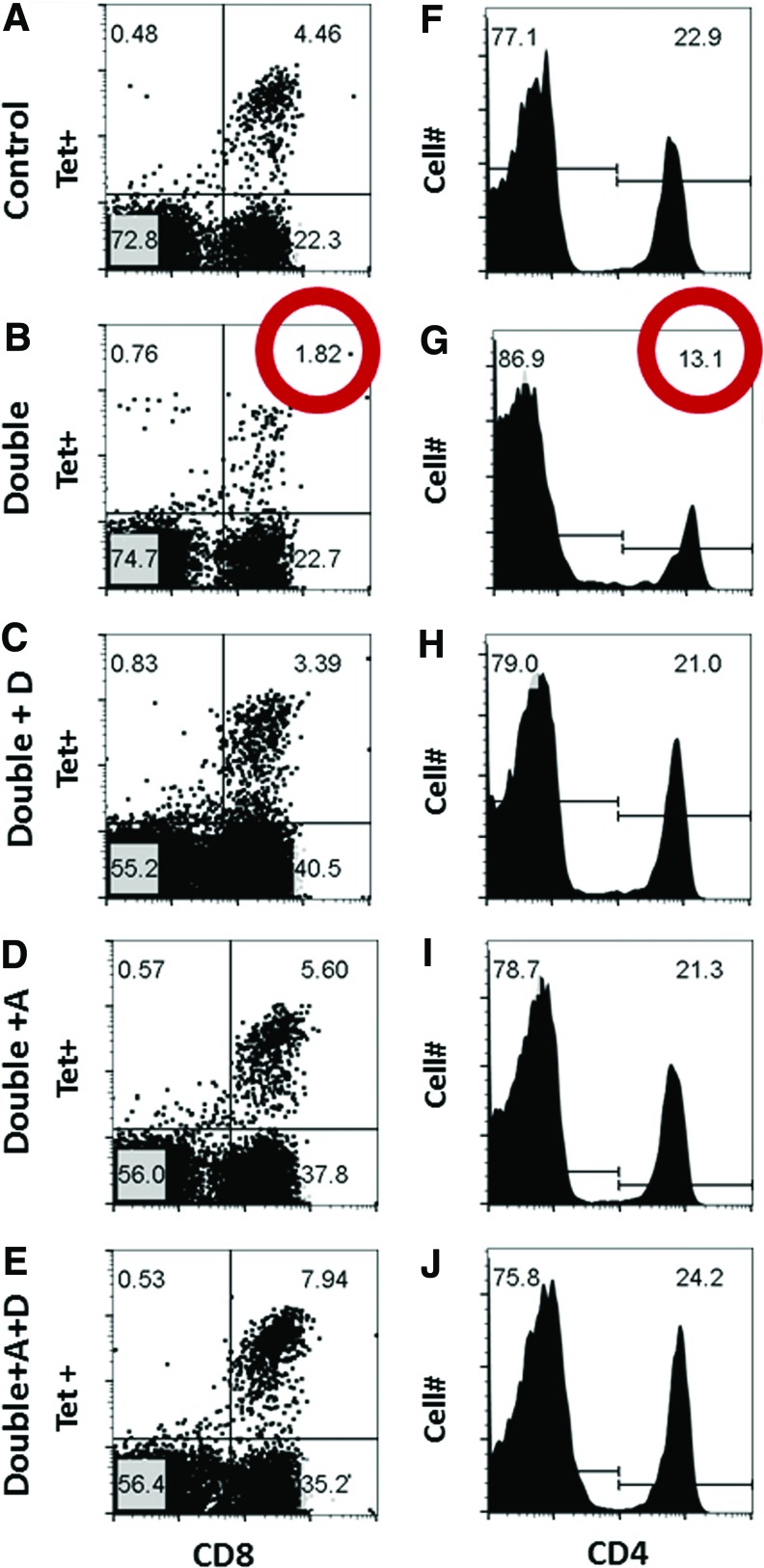

Results from flow cytometry analyses from one of the pooled experiments are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 (panels A and B) illustrates profiles of lymphocyte-gated cells, stained for CD8 and for the tetramer NP366–374/Db. We found that in mice deficient for vitamins A and D (“Double”), the percentages of CD8+ NP366–374/Db Tet+ cells among lymphocytes were lower than in controls. Reductions were observed in all four experiments, and when samples from individual mice were compared, statistically significant differences were observed between groups (Fig. 2A). When CD8+ NP366–374/Db Tet+ cells were examined as a percentage of the CD8+ population, significant differences between VAD+VDD and control mice were again identified (p = 0.003, data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Vaccine-specific T cell responses among VAD+VDD and control mice. Flow cytometry profiles (A–J) are shown for an experiment in which BAL samples were pooled within groups of mice after mice received a cold-adapted influenza virus vaccine. Day 10, lymphocyte-gated (based on FSC, SSC) BAL profiles are shown for control mice (Top row), VAD+VDD mice (second row, “Double”), VAD+VDD mice given a vitamin D supplement (third row, “Double + D”), VAD+VDD mice given a vitamin A supplement (fourth row, “Double + A”), or VAD+VDD mice given a supplement of vitamins A + D (fifth row, “Double + A+D”). In the left column, NP366–374/Db Tet+ staining is shown on the y axis and CD8+ staining is shown on the x axis. In the right column, a histogram is shown for CD4 staining. As demonstrated, VAD+VDD animals exhibited low percentages of CD8+ NP366–374/Db Tet+ and CD4+ cells compared with control animals among lymphocytes (red circles), but responses matched or exceeded normal levels when animals were supplemented with vitamins A+D. In this experiment, there were five mice per group, and samples were mixed within each group before assay. Total cell counts based on flow cytometry were 2.5 × 106 and 3.1 × 106 for VAD+VDD and control animals, respectively. BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/vim

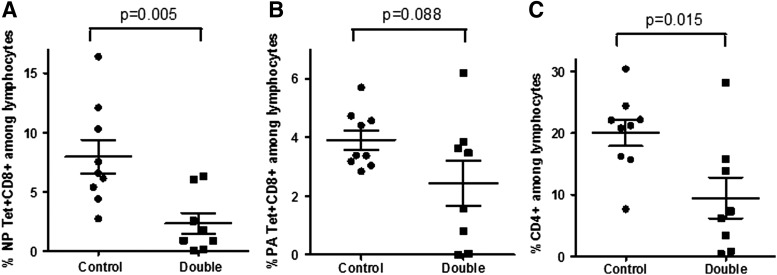

FIG. 2.

Reduced virus-specific CD8+ and CD4+ cell frequencies among airway lymphocytes in vaccinated VAD+VDD animals. Individual animals were tested in two separate experiments. Results for these combined experiments are shown to demonstrate differences between VAD+VDD animals and control animals for the percentages of NP366–374/Db Tet+ CD8+ cells (A), the percentages of PA224–233/Db Tet+ CD8+ cells (B), and the percentages of CD4+ cells (C) among airway lymphocytes in the control and VAD+VDD (“Double”) groups.

There were also trends toward reductions in all four experiments in the percentages of lymphocytes that were positive for CD8+ and PA224–233/Db Tet+. In this case, when results from individual animals were compared, the percentages of CD8+ PA224–233/Db Tet+ cells among lymphocytes did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2B, p = 0.088), but percentages of CD8+PA224–233/Db Tet+ among CD8+ cells were significantly lower in VAD+VDD mice than in controls (p = 0.016, data not shown). In addition to CD8+Tet+ cells, the total CD4+ T cells populations was reduced in VAD+VDD mice in all four experiments (Fig. 1F, G), and statistically significant differences were observed between groups when individual mice were compared (Fig. 2C, p = 0.015).

When samples from each group were combined for testing within an experiment, we were able to evaluate additional groups in which VAD+VDD mice were supplemented with one or both vitamins on days 0, 3, and 7 relative to vaccination (Fig. 1C–E, H–J). In each of these two preliminary experiments, we found that when VAD+VDD mice were vitamin supplemented, CD8+Tet+ and CD4+ T cell percentages improved to meet or exceed normal levels.

Adhesion/activation marker phenotypes among responding virus-specific T cells in VAD+VDD and control mice

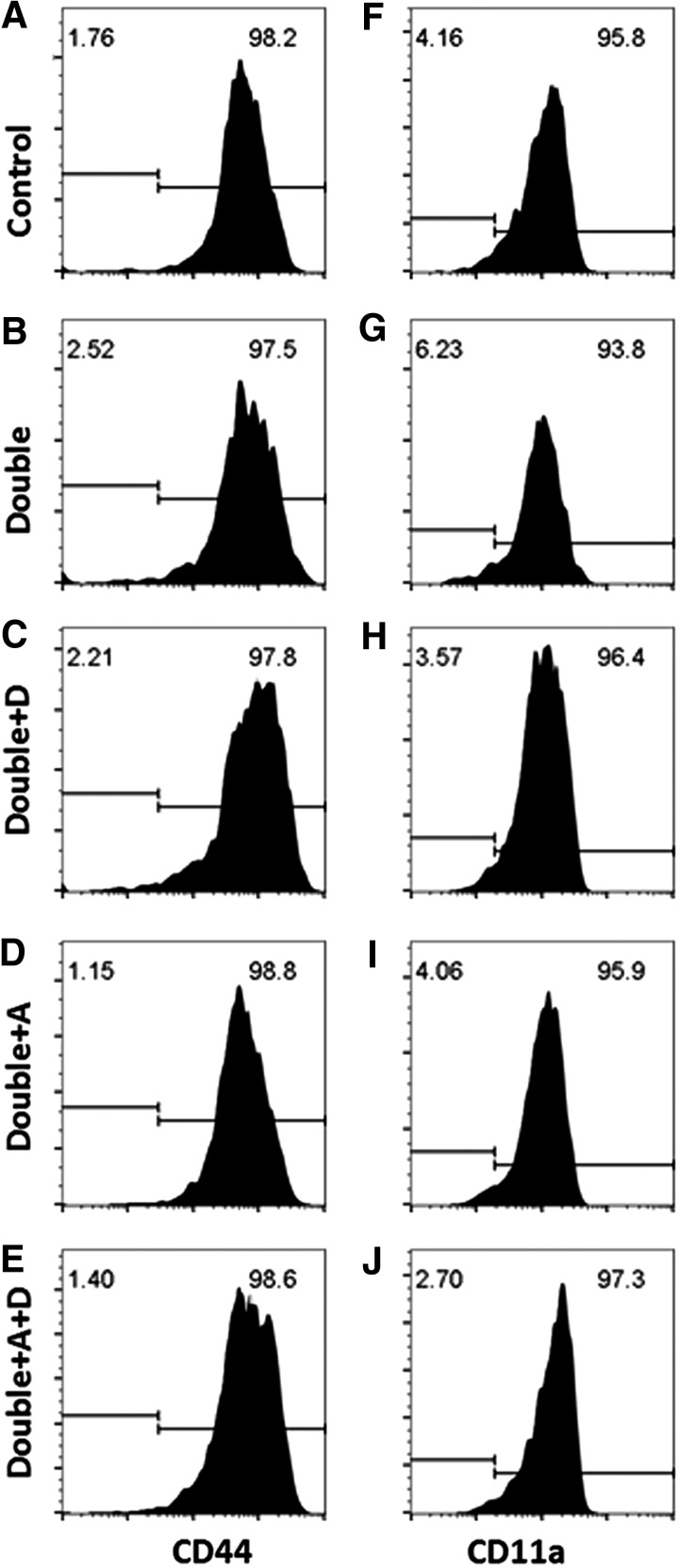

CD8+ T cells in VAD+VDD mice were tested for the expression of activation and adhesion membrane markers, including CD44, CD11a, and CD103. Results for CD44, a marker for activation, are shown in Figure 3A–E. This marker was positive on all CD8+ cells. No discernible differences were observed between cells from VAD+VDD and control animals. CD11a results are shown in Figure 3F–J. This molecule was evaluated because it pairs with CD18 to form heterodimeric LFA-1, which can support extravasation of T cells into lower respiratory tract tissues by adherence to ICAM-1 on endothelial cells (9,11,13,14). Blockade of CD11a prevents retention of cells in the lung (34). We found that all CD8+ cells in VAD+VDD animals were positive for CD11a. There was a modest reduction in median CD11a staining among CD8+ cells in VAD+VDD mice compared with controls, but the significance of these differences was not proven in our study.

FIG. 3.

CD44+ and CD11a+ cell frequencies among CD8+ cells in VAD+VDD and control mice. The phenotypes of CD8+ cells are shown with respect to membrane markers CD44 and CD11a. (A–E) illustrate the frequencies of CD44+ cells among CD8+ cells and (F–J) illustrate the frequencies of CD11a+ cells among CD8+ cells.

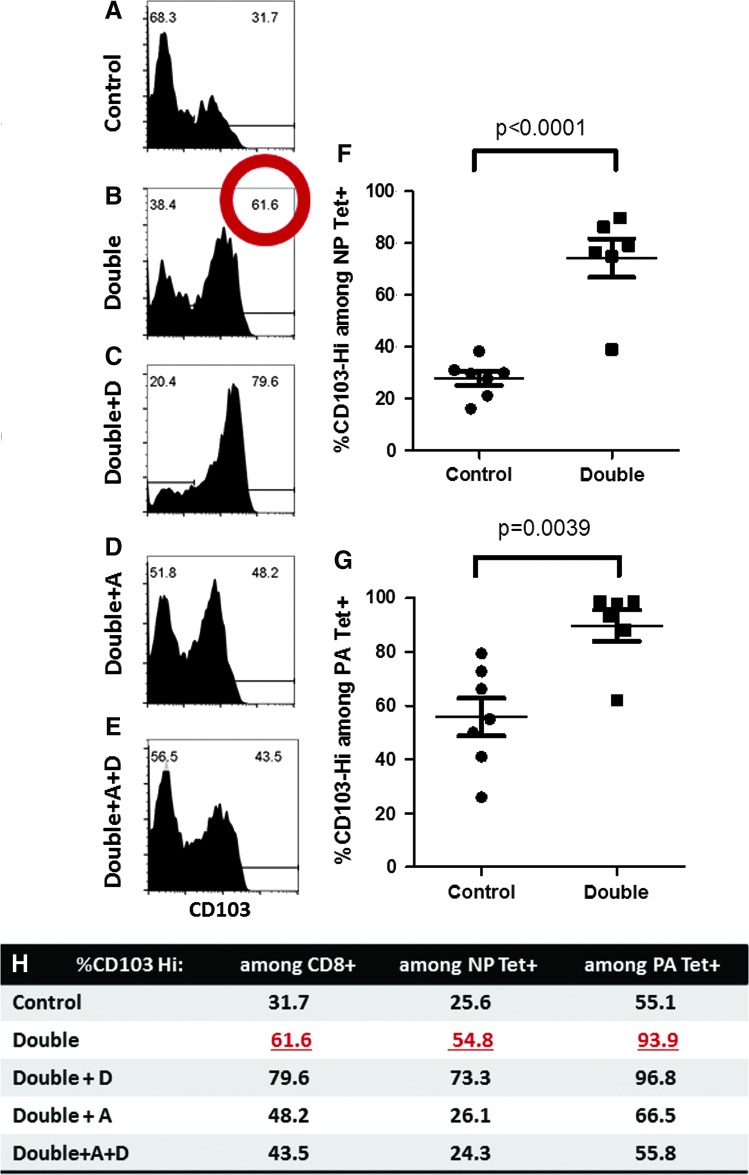

Most striking were differences in CD103 expression among CD8+ cells in VAD+VDD mice compared with controls (Fig. 4A, B). CD103 was evaluated because it binds e-cadherin, a molecule on epithelial/stromal cells in skin, kidney, the respiratory tract, and the digestive tract [and on certain inflammatory dendritic cells (7,12,16,17,24,25,28,30)]. In four of four experiments, the frequencies of CD103Hi cells among CD8+ cells increased in VAD+VDD animals compared with controls.

FIG. 4.

CD103Hi cell frequencies among CD8+ cells in VAD+VDD and control animals. The percentages of CD103Hi cells among CD8+ cells are shown (A–E). Also shown are percentages for individual mice, comparing CD103Hi cells among CD8+ cells bound by the NP366–374/Db tetramer (F) or the PA224–233/Db tetramer (G) in VAD+VDD mice compared with controls. In (H) are shown percentages for CD103Hi cells among CD8+ cells (second column), among NP366–374/Db Tet+ cells (third column), or among PA224–233/Db Tet+ cells (fourth column) in an experiment with five different mouse groups. Percentages of CD103Hi cells among CD8+ cells in VAD+VDD mice were higher than in control mice in each of four experiments (see red circle in panel B, and panel F for examples), and dropped in each of two experiments when animals were supplemented with vitamins A+D (E). CD103Hi percentages were also higher among PA224–233/Db-specific cells than among NP366–374/Db-specific cells in each of four experiments. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/vim

When results from experiments with individual mice were examined, statistically significant differences were observed between VAD+VDD and control groups for frequencies of CD103Hi cells among NP366–374/Db-specific CD8+ cells (Fig. 4F, p < 0.0001) and among PA224–233/Db-specific CD8+ cells (Fig. 4G, p = 0.0039). Of interest, the percentages of CD103Hi cells were significantly greater in PA224–233/Db-specific CD8+ cells than in NP366–374/Db-specific CD8+ cells (p = 0.003 for control animals). In a single, preliminary experiment, the frequencies of CD103Hi cells were examined among total CD4+ T cells in the BAL, and found to be significantly higher in VAD+VDD mice than in controls (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/vim). Exaggerated expression of CD103 was previously observed by us among CD8+ T cells in VAD mice (29) and by others among dendritic cells in the gut (25). In previous experiments in VAD animals, the high CD103 expression paralleled poor recruitment of CD8+ T cells into target tissues (25,28).

The differences in CD103 expression among cells responsive to NP366–374/Db and PA224–233/Db are reminiscent of previous experiments that showed disparate properties for the two T cells populations, a likely consequence of T cell receptor avidity and variant display of NP366–374/Db and PA224–233/Db epitopes by antigen-presenting cells at early and late stages after infection (2,10,35). Previous research showed that NP366–374/Db-specific cells were more prominent in lower respiratory tract tissues after a second exposure to influenza virus, whereas PA224–233/Db-specific cells were relatively rare. Further experimentation is now warranted to determine whether/how antigen might influence CD103 expression and whether/how the exaggerated expression of CD103 might inhibit recruitment of PA224–233/Db-specific cells into the airway upon T cell reactivation.

To evaluate virus-specific T cells in other locations, we tested NP366–374/Db-specific cells in lungs and nasal tissues on day 10 after cold-adapted influenza virus vaccination. Results of this single, preliminary experiment are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. As demonstrated, the NP366–374/Db-specific cells were slightly (not significantly) reduced in lung tissues and were significantly reduced in nasal tissues in VAD+VDD mice compared with controls (Supplementary Fig. S2A, B). The high frequencies of CD103Hi cells among NP366–374/Db-specific cells were preserved in parenchymal tissues, similar to the BAL (Supplementary Fig. S2C, D).

One further preliminary, single study evaluated splenic cells from naive VAD+VDD and control mice. The percentages of T cells (CD3+ cells) among lymphocytes were only slightly (not significantly) lower in VAD+VDD mouse splenocytes than in controls (Supplementary Fig. S3A), but the frequencies of CD103Hi cells among CD3+ T cells in VAD+VDD animals were significantly higher than in controls (Supplementary Fig. S3B). Included in this T cell population were CD3+, CD103Hi, CD44+ cells that were present in VAD+VDD animals, but rare in controls (Supplementary Fig. S3C).

A separate analysis of CD44+ cells among CD3+ cells, or CD11a+ cells among CD3+ cells, demonstrated no significant differences between animal groups (data not shown). In total, results revealed an abnormality of T cells populations in VAD+VDD animals, affecting both mucosal and peripheral tissues, in the presence or absence of vaccination.

The increase in frequency of CD103Hi cells among CD8+ cells in the BAL of VAD+VDD animals was reduced in two of two experiments when VAD+VDD animals were supplemented with vitamins A or A + D (Fig. 4D, E, H), suggesting that the CD103 upregulation was dependent on the VAD phenotype. This was the case for both NP366–374/Db-specific and PA224–233/Db-specific CD8+ cells.

Overall conclusions

Data show that VAD+VDD animals exhibit low percentages of virus-specific CD8+ T cells among respiratory lymphocytes after vaccination with a cold-adapted influenza virus vaccine. Cells that reached the airway exhibited abnormally high CD103 membrane protein expression, more prominent among PA224–233/Db-specific cells than among NP366–374/Db-specific cells.

Given our previous and current findings that (1) normal animals respond to respiratory viral antigens by recruitment of CD8+ T cells with cytotoxic function to the respiratory tract (28), (2) T cells are poorly recruited to the airway in VAD or VAD+VDD animals in response to viral antigens (29), and (3) vitamin-deficient (VAD) mice clear virus and viral antigens more slowly than controls (27), we suggest that important virus-specific T cell effector functions are compromised in the context of vitamin deficiency. Fortunately, in each of the two preliminary experiments in which VAD+VDD mice were supplemented with vitamins A + D on days 0, 3, and 7 relative to vaccination, improvements in virus-specific T cell frequencies and corrections of the CD103Hi phenotypes were observed.

We consider that our T cell [and antibody (33)] results may help to explain disappointing immune responses observed in recent clinical influenza vaccine programs. In a previous study with the FluMist influenza virus vaccine, the seroconversion/seroresponse among all study participants toward A/H1 N1 or A/H3 N2 was <10% (3). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently withdrew its recommendation for the use of live attenuated influenza virus vaccines (31). Given that vitamin deficiencies and insufficiencies are now frequent in both developed and developing countries (20), we encourage clinical vaccine developers to monitor vitamins routinely among vaccine recipients. Perhaps the partnering of influenza virus vaccination with vitamin supplementation programs could improve vaccine-induced immune responses and overall health, as has been observed in WHO-sponsored vitamin supplementation programs in the developing world (32).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by NIH NIAID R01 AI088729, NCI P30-CA21769, and ALSAC.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Altman JD, Moss PA, Goulder PJ, et al. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 1996;274:94–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballesteros-Tato A, Leon B, Lee BO, et al. Epitope-specific regulation of memory programming by differential duration of antigen presentation to influenza-specific CD8(+) T cells. Immunity 2014;41:127–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block SL, Falloon J, Hirschfield JA, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a quadrivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:745–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenberg M, Connolly DM, and Freedberg IM. Regulation of keratin gene expression: the role of the nuclear receptors for retinoic acid, thyroid hormone, and vitamin D3. J Invest Dermatol 1992;98:42S–49S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botling J, Oberg F, Torma H, et al. Vitamin D3- and retinoic acid-induced monocytic differentiation: interactions between the endogenous vitamin D3 receptor, retinoic acid receptors, and retinoid X receptors in U-937 cells. Cell Growth Differ 1996;7:1239–1249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlberg C. Mechanisms of nuclear signalling by vitamin D3. Interplay with retinoid and thyroid hormone signalling. Eur J Biochem 1995;231:517–527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey KA, Fraser KA, Schenkel JM, et al. Antigen-independent differentiation and maintenance of effector-like resident memory T cells in tissues. J Immunol 2012;188:4866–4875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole GA, Hogg TL, and Woodland DL. The MHC class I-restricted T cell response to Sendai virus infection in C57BL/6 mice: a single immunodominant epitope elicits an extremely diverse repertoire of T cells. Int Immunol 1994;6:1767–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Constantin G, Majeed M, Giagulli C, et al. Chemokines trigger immediate beta2 integrin affinity and mobility changes: differential regulation and roles in lymphocyte arrest under flow. Immunity 2000;13:759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowe SR, Turner SJ, Miller SC, et al. Differential antigen presentation regulates the changing patterns of CD8+ T cell immunodominance in primary and secondary influenza virus infections. J Exp Med 2003;198:399–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon AE, Mandac JB, Martin PJ, et al. Adherence of adoptively transferred alloreactive Th1 cells in lung: partial dependence on LFA-1 and ICAM-1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000;279:L583–L591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogan A, Wang ZD, and Spencer J. E-cadherin expression in intestinal epithelium. J Clin Pathol 1995;48:143–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dustin ML, and Springer TA. T-cell receptor cross-linking transiently stimulates adhesiveness through LFA-1. Nature 1989;341:619–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ely KH, Cookenham T, Roberts AD, et al. Memory T cells populations in the lung airways are maintained by continual recruitment. J Immunol 2006;176:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans RM, and Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors, RXR, and the big bang. Cell 2014;157:255–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heath WR, and Carbone FR. The skin-resident and migratory immune system in steady state and memory: innate lymphocytes, dendritic cells and T cells. Nat Immunol 2013;14:978–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann M, and Pircher H. E-cadherin promotes accumulation of a unique memory CD8 T-cell population in murine salivary glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:16741–16746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huber VC, Thomas PG, and McCullers JA. A multi-valent vaccine approach that elicits broad immunity within an influenza subtype. Vaccine 2009;27:1192–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin H, Zhou H, Lu B, et al. Imparting temperature sensitivity and attenuation in ferrets to A/Puerto Rico/8/34 influenza virus by transferring the genetic signature for temperature sensitivity from cold-adapted A/Ann Arbor/6/60. J Virol 2004;78:995–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones BG, Oshansky CM, Bajracharya R, et al. Retinol binding protein and vitamin D associations with serum antibody isotypes, serum influenza virus-specific neutralizing activities and airway cytokine profiles. Clin Exp Immunol 2016;183:239–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. Retinoid X receptor interacts with nuclear receptors in retinoic acid, thyroid hormone and vitamin D3 signalling. Nature 1992;355:446–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koszewski NJ, Herberth J, and Malluche HH. Retinoic acid receptor gamma 2 interactions with vitamin D response elements. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;120:200–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krasowski MD, Ni A, Hagey LR, et al. Evolution of promiscuous nuclear hormone receptors: LXR, FXR, VDR, PXR, and CAR. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2011;334:39–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackay LK, Rahimpour A, Ma JZ, et al. The developmental pathway for CD103(+)CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat Immunol 2013;14:1294–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mora JR, Iwata M, and von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:685–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Suresh M, et al. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 1998;8:177–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penkert RR, Surman SL, Jones BG, et al. Vitamin A deficient mice exhibit increased viral antigens and enhanced cytokine/chemokine production in nasal tissues following respiratory virus infection despite the presence of FoxP3+ T cells. Int Immunol 2016;28:139–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudraraju R, Surman S, Jones B, et al. Phenotypes and functions of persistent Sendai virus-induced antibody forming cells and CD8+ T cells in diffuse nasal-associated lymphoid tissue typify lymphocyte responses of the gut. Virology 2011;410:429–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudraraju R, Surman SL, Jones BG, et al. Reduced frequencies and heightened CD103 expression among virus-induced CD8(+) T cells in the respiratory tract airways of vitamin A-deficient mice. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012;19:757–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddiqui KR, Laffont S, and Powrie F. E-cadherin marks a subset of inflammatory dendritic cells that promote T cell-mediated colitis. Immunity 2010;32:557–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Small PA, Jr., and Cronin BJ. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' controversial recommendation against the use of live attenuated influenza vaccine is based on a biased study design that ignores secondary protection. Vaccine 2017;35:1110–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sommer A. Vitamin A, infectious disease, and childhood mortality: a 2 cent solution? J Infect Dis 1993;167:1003–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Surman SL, Penkert RR, Jones BG, et al. Vitamin supplementation at the time of immunization with cold-adapted influenza virus vaccine corrects poor antibody responses in mice deficient for vitamins A and D. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2016;23:219–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thatte J, Dabak V, Williams MB, et al. LFA-1 is required for retention of effector CD8 T cells in mouse lungs. Blood 2003;101:4916–4922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valkenburg SA, Gras S, Guillonneau C, et al. Protective efficacy of cross-reactive CD8+ T cells recognising mutant viral epitopes depends on peptide-MHC-I structural interactions and T cell activation threshold. PLoS Pathog 2010;6:e1001039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.