Abstract

Where does cancer come from? Although the cell-of-origin is difficult to pinpoint, cancer clones harbor information about their clonal ancestries. In an effort to find cells before they evolve into a life-threatening cancer, physicians currently diagnose premalignant diseases at frequencies that substantially exceed those of clinical cancers. Cancer risk prediction relies on our ability to distinguish between which premalignant features will lead to cancer mortality and which are characteristic of inconsequential disease. Here, we review the evolution of cancer from premalignant disease, and discuss the concept that even phenotypically normal cell progenies inherently gain more malignant potential with age. We describe the hurdles of prognosticating cancer risk in premalignant disease by making reference to the underlying continuous and multivariate natures of genotypes and phenotypes and the particular challenge inherent in defining a cell lineage as “cancerized.”

Tissues diagnosed as cancerous, precancerous, and normal can share genetic abnormalities and phenotypic traits. Efforts to characterize premalignancy more precisely are important for cancer detection, prevention, and therapy.

As the second-leading cause of death worldwide after cardiovascular disease, cancer claimed >14 million lives in 2012 (Torre et al. 2015). This number is expected to increase over the next few decades as a result of the aging human population and increasing prevalence of cancer risk factors worldwide. Although this statistic is alarming from a public health perspective, we must initially pose the question, “what exactly constitutes a cancer case?” With advancement of basic biological understanding, the definition of cancer itself has continued to evolve over the past 2000 years. In fact, even current established hallmarks of malignancy (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011) continue to be revised and reveal the complexity involved in distinguishing between cancerous and noncancerous tissue. In a literal sense, global regions may differ in clinical definitions of the morphological threshold between a preinvasive carcinoma in situ and an invasive tumor (terms defined in detail below), and even within an individual hospital two pathologists may disagree whether a diagnosis of dysplasia versus malignancy should be applied to a particular biopsy specimen. The ability to identify a precancerous state has a major influence on our understanding of cancer prevalence and hence our aims for cancer detection, prevention, and therapy.

Underlying these ambiguities is the fact that cancer progression is a stochastic process that occurs through somatic evolution (Nordling 1953; Nowell 1976; Vogelstein and Kinzler 2004; Merlo et al. 2006; Yates and Campbell 2012). How is the initial cancer cell initiated? From early development until death, normal dividing cells within the body act as asexual, quasi-organisms subject to evolutionary pressure from microenvironmental constraints. Because of imperfect DNA replication and carcinogen exposure, somatic genomic abnormalities (SGAs; such as point mutations and copy number alterations, and epigenetic changes) accumulate and some may confer a fitness advantage, such as increased reproductive rate. Advantageous alterations, often known as “drivers,” will be clonally selected. Within a selected clone, subsequent driver mutations may be acquired, leading to subclonal expansions and branched lineages from the genotype of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of the clone.

This microevolutionary process of Darwinian natural selection on the timescale of the human lifetime can produce genetically diverse clonal populations, tumors with complex clonal architectures and heterogeneous tissue microenvironments (Michor et al. 2003; Merlo et al. 2006; Graham and McDonald 2010; Baker et al. 2013; Greaves 2015). Eventual neoplasms also show marked heterogeneity in their cellular morphology and clonal architecture (Greaves and Maley 2012). Consequently, although there are definitive clinical phenotypes identified through the natural history of a disease (e.g., the adenoma–carcinoma paradigm in colorectal cancer [CRC] progression), there, in fact, exists a “continuum” of cell types, both genetically and phenotypically speaking, throughout all stages of carcinogenesis.

A main focus of this work will be the relationship between genotype and phenotype, including the impact of defining disease progression based on histology (e.g., the Barrett’s metaplasia–dysplasia–cancer sequence) versus genetic composition (e.g., the sequential or otherwise acquisition of genetic changes). The “closeness to cancer” is typically categorized by histology, as most epidemiological studies aim to assess cancer risk in a group of people with a particular disease stratified by clinical stage of neoplastic progression, such as comparing cancer development risk in Barrett’s esophagus (BE) patients without dysplasia versus patients with high-grade dysplasia (HGD). There are many defined premalignant, or precancerous, diseases that confer a higher risk of cancer progression versus that of a nonaffected individual (Table 1) (Fitzgerald 2010).

Table 1.

Types of precancerous conditions

| Cancer | Premalignant | Preinvasive | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esophagus | Barrett’s esophagus (BE) | High-grade dysplasia (HGD) | Kaz et al. 2015 |

| Colorectum | Ulcerative colitis (UC) Crohn’s disease | Adenoma High-grade dysplasia | Yashiro 2014, 2015; Jawad et al. 2011; Galandiuk et al. 2012 |

| Breast | Proliferative disease HELU | ADH/ALH FEA Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) | Coradini and Oriana 2014; Aulmann et al. 2009; Cole et al. 2010; Hartmann et al. 2015; Pinder 2010; Virnig et al. 2010 |

| Pancreas | PanIN1 | Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) | Hruban and Fukushima 2007 |

| Prostate | Proliferative inflammatory atrophy? | Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) | Kryvenko et al. 2012; Bostwick and Cheng 2012 |

| Cervix | ASC (atypical squamous cells)/LSIL (low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions) | HSIL/CIN3 | Burd 2003; Barron et al. 2014 |

| Bladder | Intestinal metaplasia Papillary urothelial hyperplasia | Bladder carcinoma in situ Noninvasive papillary carcinoma | Gordetsky and Epstein 2015 Lopez-Beltran et al. 2013 |

| Stomach | Intestinal metaplasia (IM) of the stomach | High-grade dysplasia | Yakirevich and Resnick 2013 |

| Skin | Xeroderma pigmentosum Porokeratosis Melanocytic hyperplasia Dysplastic nevus | Bowen’s disease Actinic keratosis (AK) Lentigo maligna | Smoller 2006; Shain et al. 2015 |

| Lung | Squamous metaplasia Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia | Squamous carcinoma in situ (CIS) | Wistuba 2005; Mori et al. 2001 |

| Mouth | Oral premalignant lesions (OPML): leukoplakia, erythroplakia, lichen planus | Oral epithelial dysplasia, CIS | Reibel 2003 |

| Anus | HPV infection/ ASC-US (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance) | Anal intraepithelial lesions (AIL) | Echenique and Phillips 2011 |

| Kidney | Von Hippel Lindau | Renal intraepithelial lesions (RIL) | Poppel et al. 2000 |

| Ovary | SCOUT Secretory cell outgrowth (serous) | Serous tubular intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) | Kurman and Shih 2010 |

In this review, we will question exactly what constitutes premalignant disease. From the view of multistage theory (Moolgavkar 1978), does in fact every malignancy originate from a premalignant cell progeny that could theoretically be detected by a perfectly sensitive screen? Biologically, is a first malignant cell ever born de novo, that is, it inherits no SGAs known to increase cancer risk nor has a phenotypically premalignant ancestor cell? And most important, can we reduce cancer mortality by identifying certain premalignant changes early?

To address the first questions, we know that (usually) cancer arises monoclonally from a cell lineage that acquired multiple mutations in cancer-associated genes such as tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) and oncogenes (Michor et al. 2004, Vogelstein et al. 2013) and/or numerous epigenetic alterations (Feinberg et al. 2016). As an example, Knudson (1971) famously showed that retinoblastoma in children was caused by two rate-limiting events, the biallelic inactivation of TSG RB1. If a child inherits a single inactivated allele, this event translates to a single “hit” or initiating event. Next, the inactivation of this TSG initiates clonal expansion of mutated cells because it permits unsuppressed cell proliferation, the sine qua non of carcinogenesis (Moolgavkar and Knudson 1981). However, covert premalignant lesions already exist in relatively high percentages in infants—1% of all newborns were found to have cells with acute lymphoblastic leukemia mutation and histopathologically identifiable precursor lesions, 100 times the corresponding clinical cancer rates (Mori et al. 2002). Notably, such early genetic events have been found in monozygotic twins who share the same premalignant clones in utero (Greaves et al. 2003). Thus, there is evidence that even childhood cancers that require few mutations for a malignant phenotype are initiated from a premalignant clone, and even normal fetal development produces silent, genetically diverse premalignant lesions. Further, regardless of stochastic clone fate, cell lineage-tracing experiments suggest that clonal diversity generated by neutral drift of actively self-renewing stem cells may be a universal pattern in all stem cell compartments necessary to achieve homeostasis (Klein and Simons 2011; Blanpain and Simons 2013). This is found strikingly in aging populations, with 10% of adults over age 65 having multiple somatic mutations in their blood cells, frequently in three genes that have been previously implicated in hematologic cancers (Genovese et al. 2014).

Here, we discuss the controversies surrounding the semantics of premalignant disease and review some main aspects of premalignant evolution such as accumulation of driver mutations, influence of tissue architecture, tissue aging, and roles of the microenvironment. Lastly, we examine some important implications in disease prognostication and patient management.

WHAT IS PREMALIGNANCY?

The term “premalignant” describes a condition that may (or is likely to) become cancer (National Cancer Institute 2016). In practice, the meaning of this term may differ between geneticist, pathologist, physician, and politician. For the purposes of this review, we will refer to “premalignant” conditions as all clinically diagnosed morphological lesions known to be a precursor to a certain malignancy and thus they increase an individual’s risk of developing cancer. We note that it may be the case that not all morphological changes that are associated with an overall increase in cancer risk are themselves premalignant; some benign abnormal lesions will never progress to a neoplasm with time. Alternatively, progression to a neoplasm is also not a prerequisite for a lesion to be termed premalignant—in fact, most premalignant lesions remain benign throughout the lifetime of a host individual, as evidenced by their current higher diagnosed frequencies than that of their associated neoplasms. The term “precancer” used in this article encompasses “premalignant” tissues including metaplasia like BE and also the (presumptively named) “preinvasive” neoplastic lesions including dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. Preinvasive lesions are neoplasms that have neither developed the ability to penetrate deeper layers of epithelium nor acquired the propensity to metastasize and grow in other parts of the body (again, we note later that it may be that some so-called preinvasive lesions will never invade). We provide examples with references of such precancerous conditions for the most common epithelial cancers in Table 1. The extensiveness of this list highlights the high prevalence of cancer precursors being diagnosed in current medical practice and prompts the hypothesis that in fact every epithelial cancer arises from a potentially detectable precancerous condition.

It is interesting to note that there has been considerable controversy within the medical community about whether some lesions such as carcinoma in situ should be classified as cancer or precancer, especially in regard to particular cancer sites (Esserman et al. 2014; Greaves 2014). Notably, the incidence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast has dramatically increased as a result of increased mammography screening in the past three decades, currently constituting 20% to 25% of all screen-detected breast cancers in the United States in women ages 40 to 64 (Virnig et al. 2010). Thus, mammography has often been heralded as a true success story for the goal of screening: to detect precancerous or early cancer lesions to intervene with treatment before invasive cancer (potentially) develops. However, cancer screening can bring harms along with benefits. A recent observational study of >100,000 women in the United States diagnosed with DCIS found that cancer-specific mortality was only 3.3% (95% CI, 3.0%–3.6%) at 20 years (Narod et al. 2015). In fact, <1% of the patients in this 20-year study by Narod and colleagues died from breast cancer. We note that all patients in this study received some kind of intervention (mostly, surgery and less often radiation therapy) and so the true “unperturbed” natural history of DCIS left in situ remains unknown (and indeed this is a common issue across tissues). Nevertheless, in response to this study, numerous dichotomizing editorials have been written, some proposing the reconsideration of unnecessary, aggressive therapy for DCIS and even the reassessment of whether the goal of breast cancer screening should be to detect these clustered amorphous calcifications (Esserman and Yau 2015). Others are reluctant to support allegations of overdiagnosis (precancers detected at screening that would not have otherwise become clinically apparent or cause death) and/or overtreatment that may lead to decreased screening efforts for such a prominent women's health issue (Recht et al. 2016). This is supported by a UK meta-analysis of breast cancer screening trials that concluded that screening recommendations are more beneficial than harmful; the findings predict that for every single breast cancer death averted, about three overdiagnosed cases would be treated (Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening 2012). These studies shed light on the oftentimes political and psychological aspects of using a term that literally translates to “cancer in place” versus “premalignant,” and perhaps motivate the adoption of an even less loaded term such as “abnormal” that does not necessarily imply a relationship to cancer at all. Consequently, a recent U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) working group on cancer screening suggested that even the term “cancer” should be reserved for describing “lesions with a reasonable likelihood of lethal progression if left untreated” (Esserman et al. 2013), although the issue remains contentious.

Precancerous phenotypes, including those provided in Table 1, are diagnosed based on the morphological features of a tissue. However, these can be further subdivided into tissue-specific phenotypic groups at smaller scales, the range of which resides in a hypothetical, infinite space known as “phenotype space.” Additionally, the advancement of genomic analysis technology has enabled extensive analyses of the “genotype space” of tissues, defined by the complex patterns of DNA mutations and chromosomal alterations observed in premalignant cells. The ultimate goal of modern genetics is to understand how genotype relates to phenotype (Botstein and Risch 2003; Benfey and Mitchell-Olds 2008; Rockman 2008). In mathematical terms, the genotype–phenotype (G-P) map is surjective (for each phenotype there exists at least one genotype that maps to that point in phenotype space) but it is not one-to-one; the notion of a “genetic blueprint” of precancerous and associated cancerous tissues is inadequate, because research continues to show that the relationship between the two spaces is complex (Pigliucci 2010; Nuzhdin et al. 2012). For instance, many genetic alterations may be evolutionarily neutral, and thus have no consequence for the phenotype at all, or certain phenotypic traits may only be “expressed” in certain microenvironmental contexts.

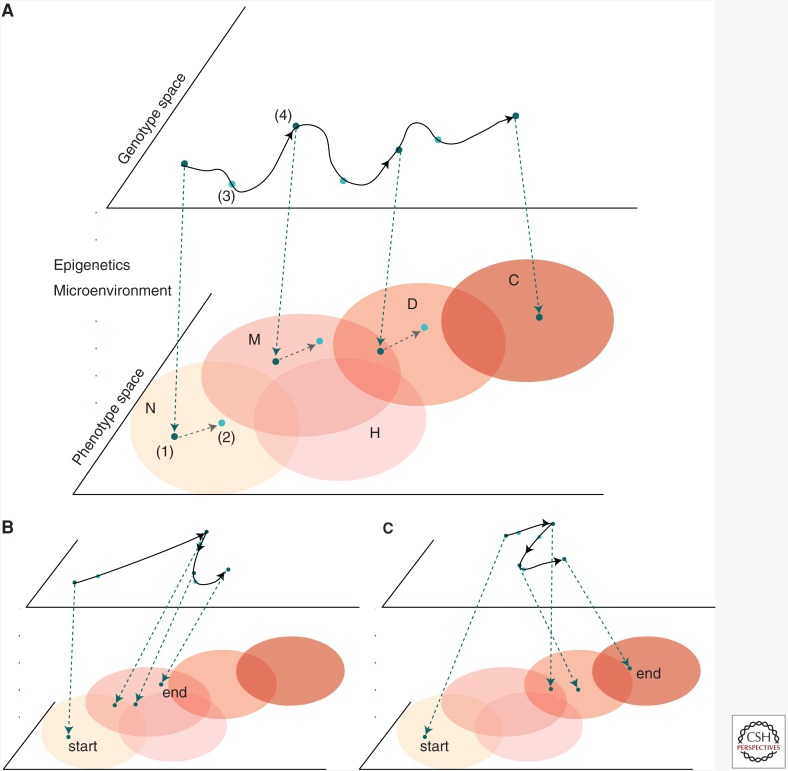

In Figure 1, we provide an example of an evolutionary trajectory of an individual’s genotype mapping to a canonical paradigm of tissue progression (such as seen in BE) through normal, metaplastic, dysplastic, and finally cancer regions in phenotypic space. The outline of the process is: random mutation occurs on the genotype level, pleiotropic effects of such a variant on the phenotype are determined by the G-P map, and finally the phenotype interacts with the environment, and indeed may be modulated by the microenvironment (Houle et al. 2010; Chandler et al. 2013). Natural selection will tend to cause the clonal expansion of the most fit phenotypes in the current microenvironmental context. Analyzing the properties of evolutionary pressures influencing regulatory networks and associated phenotypes helps us to learn the causal relationships captured by the G-P map (Chanock et al. 2007; Gagneur et al. 2013). The overlapping areas in phenotypic space qualitatively illustrate the issue of ambiguity in categorizing phenotypes during neoplastic progression. Thus, although a diagnosis in the clinic is chosen from a handful of pathological stages, the underlying multivariate natures of genotypes and phenotypes means that such classifications are in fact continuous and fluid. This continuity perhaps explains some of the evident challenges in reliably identifying particular premalignant states, such as a low-grade dysplasia (LGD) in BE (Kerkhof et al. 2007; Curvers et al. 2010).

Figure 1.

Trajectory of premalignant evolution via the genotype–phenotype (G-P) map. The G-P map traces the evolutionary path of cells in the two infinite spaces of genotype and phenotype. (A) Time points are specified to illustrate the progression through phenotype space (pink regions denote regions of similar phenotype) from normal to precancerous to cancer, driven by changes in genotype. Movement through the spaces is caused by: (1) the projection of the genotype through epigenetic and microenvironmental “filters” accounted for in the G-P map that produces a phenotype from a genotype; (2) the action of natural selection in the phenotype space, influencing-variation generated in genotype space that moves the population to points of higher (contextual) fitness; (3) genotype of fit parents is preserved deterministically; (4) somatic mutation and/or other genetic event(s) moves average point in genotype space. We highlight the overlap in defined phenotypic regions—at one time point during progression to cancer, this cell population could be classified as either metaplastic or dysplastic histologically. (B) A second example of a stochastic trajectory that jumps as a result of a punctuated event in genotype space, such as whole-genome doubling, without discernable phenotypic change. (C) Small changes in genotype space may also lead to large changes in phenotype space possibly caused by rare variants having large phenotypic effects, epistatic effects between accumulated mutations, and/or other epigenetic or microenvironmental effects. For example, a TP53 inactivating mutation may occur in morphologically normal tissue, but not be selected until subsequent events (e.g., genome doubling) occurs. N, normal tissue; M, metaplasia; H, hyperplasia; D, dysplasia; C, cancer.

ROLE OF DRIVER ALTERATIONS IN PREMALIGNANT EVOLUTION

Although pathological assessment of the presence or absence of premalignant phenotypes remains the gold standard for cancer risk, somatic mutations that naturally occur throughout a human lifetime may also reveal information about the progress toward cancer long before a phenotype such as dysplasia manifests in a tissue (see Fig. 1). During neoplastic evolution, we typically differentiate between “driver” mutations, defined to be those that confer growth or survival advantages to cells that will be positively selected during the evolution of a cell lineage (presumably only when the mutant cells find themselves in the correct microenvironment), and “neutral,” or “hitchhiker,” mutations that passively accumulate in cell progenies (Calabrese et al. 2004; Stratton et al. 2009; Greaves 2015). Generally, lesions with driver mutations are associated with clonal expansion and are found more frequently in premalignant and malignant lesions than is expected from the normal background mutation rate (Maley et al. 2004, Lawrence et al. 2014). However, the exact role(s) of driver mutations in premalignant evolution remains elusive, even with the vast amounts of genetic and epigenetic information on cell lineages being generated through increasingly high-throughput, cost-effective genome-wide assays (Metzker 2010). This is partly because of the fact that, beyond the identification of selected mutations in premalignant tissues, such as APC biallelic inactivation in colorectal adenomas (Shibata et al. 1997), TP53 inactivation in BE (Barrett et al. 1999), and BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in premalignant breast and ovarian tissues (Welsch and King 2001; Antoniou et al. 2003), the influence that these mutations have on carcinogenesis is both context and stage-specific. As a recent example, Weaver and colleagues (2014) found that even common mutations in SMAD4 and TP53 in BE were not strictly pathological grade-specific, thus decreasing their prognostic power as an unequivocal driver for neoplastic progression. Moreover, rather than relying on a single key driver mutation as necessary for premalignant initiation, there is evidence that premalignant lesions accumulate a “full house” of driver mutations before a first malignant cell is born and then subsequent subclonal expansions within a tumor occur neutrally (Sottoriva et al. 2015; Williams et al. 2016).

Genetic diversity itself may act as a proxy for cancer development risk, regardless whether or not the collection of mutations assayed is purely advantageous and cancer-promoting, because the degree of genetic heterogeneity correlates with the probability that the population will contain (or perhaps generate) a “well-adapted” clone capable of initiating tumor growth. Clonal diversity is highly prognostic in the premalignant condition BE (Maley et al. 2006), and, surprisingly, in the example of BE may remain at relatively constant levels for a number of years (Martinez et al. 2016). The potential utility of clonal diversity as a prognostic measure across disease types was underlined by a recent pancancer study (Andor et al. 2016).

Is the term “driver” useful when thinking about carcinogenesis in premalignant disease? Many so-called driver alterations are also found in normal and premalignant tissues, occasionally at even higher frequencies than found in corresponding malignancies (Kato et al. 2016). As a recent example, Martincorena and colleagues found putative driver mutations in 18% to 32% of normal, sun-exposed skin cells at a density of ∼140 driver mutations per square centimeter (Martincorena et al. 2015). Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are also found to have putative driver mutations in nondysplastic tissue, with mutations in TP53 TSG being detected commonly in patients who subsequently develop cancer (Leedham et al. 2009; Galandiuk et al. 2012). How can such large numbers of cancer-causing mutations maintain benign phenotypes? One possibility could be that early driver mutations may not greatly increase a clone’s malignant potential without additional genetic events. Bass and colleagues found TP53 mutation to be an early event in esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) tumorigenesis, as it was found in concomitant nondysplastic BE tissue (Stachler et al. 2015). The investigators suggest, however, that the early acquisition of this founder TSG mutation alone in nondysplastic BE will most likely never progress to EAC unless cells also undergo whole-genome doubling as a catastrophic chromosomal event.

A second, perhaps more important feature is that the fitness advantage bestowed by driver mutations is inherently context-specific, such that a particular mutation will only be beneficial to the cell within the correct microenvironment. TP53 mutation in the intestine is a good example of context-dependent fitness: in an inducible mouse model, TP53-mutant clones only had a fitness advantage in a chronic inflammatory setting, whereas in normal epithelium they were subject to neutral drift (Vermeulen et al. 2013). Consequently, simply “counting” driver mutations is likely to be an inadequate way to understand premalignant disease; attention must also be paid to the evolution of a tumor-promoting or at least tumor-permissive microenvironment in tandem with the evolution of tumor cells themselves.

Expanding on this perspective, many traditional models of carcinogenesis, wherein selected driver mutations gradually accumulate and increase cancer risk, may actually conflate multiple distinct mechanisms for malignant transformation. There is often undue significance for subsequent cancer risk attributed to mutation of the pretumor cells themselves. Two examples of these anomalies to traditional carcinogenesis models are illustrated in Figure 1B, wherein a stochastic jump in genotype space to an abnormality such as whole-genome doubling results in evolutionary stasis in metaplastic phenotype, and Figure 1C, wherein a relatively unchanged genotype progresses from normal to cancer phenotype, perhaps because of extrinsic factors (e.g., changes to the microenvironmental or immune landscape) and/or epigenetic alterations.

Herein lies our main question—what constitutes a premalignant cell? Most cells harboring so-called driver mutations that are common in premalignant disease will never evolve to manifest an invasive malignant phenotype. Is premalignancy then a disease unto itself, regardless of its connection to cancer? Some premalignant diseases require surgery to alleviate symptoms that is irrespective of possible future cancer, such as colectomy for patients suffering from severe colitis symptoms. On the other hand, patients with colorectal adenomas that persist in prolonged evolutionary stasis are also considered at risk for CRC but evidence suggests that patients could often live out their lives with these benign premalignant lesions that never progress (Hofstad et al. 1996).

As evidenced in the previous section, the entire human body, from birth until death, fosters mutations that could lead to cancer if other factors conspire jointly to bring about a cancer phenotype in a tissue. Therefore, our current definition of “premalignant” as “the presence of abnormal tissue that is currently considered a cancer precursor and is associated with an increased cancer risk” is terribly unspecific because arguably all the renewing cells in our body undergo somatic evolution that lead to cancer—in a sense the entire body is therefore premalignant! We need a diagnosis of “premalignancy” to identify cells that are “more at risk” (or particularly at risk) of producing a cancer cell as we age, therefore we require a narrower definition of premalignancy based on an assemblage of factors (when mutations occurred, in what permissive microenvironment, and in tandem with what epi[genetic] alterations and phenotype) to enable effective prognostication (and clinical utility).

QUANTIFYING THE PACE AND PATTERN OF EVOLUTION

The debate continues whether premalignant clonal populations most often evolve gradually through a sequence of genetic alterations and waves of subsequent expansions that reach fixation in a tissue, or rather if they remain relatively unchanged for long periods of time then suffer rare, yet “catastrophic,” genetic events that cause large leaps toward malignancy. There is increasing evidence supporting the latter pathway, known as punctuated equilibrium (Cross et al. 2016). This process allows numerous intermixed subclones to coevolve covertly before rare clonal expansions occur owing to punctuated events such as phenotype change driven by epistatic interaction following the acquisition of a “full house” of genetic alterations or high-impact individual mutations, or possibly by large-scale rearrangements of the genome such as chromothripsis or whole-genome doubling (Stephens et al. 2011; Greaves 2015; Reid and Paulson 2015; Sottoriva et al. 2015; Williams et al. 2016). For practical purposes, how can we detect the likelihood of such “catastrophic” events in vivo during premalignant evolution? How much information about future cancer progression is predetermined early enough in preneoplastic progression to be useful clinically? Most current phylogenetic analyses that infer clonal patterns and relationships using phylogenetic theory rely on measurements at a single time point, and thus typically cannot resolve missing pieces of information such as the temporal order of early events that have already become clonal, nor detect ancestral clones that went extinct (the evolutionary “dead ends”). However, serial and spatially extensive sampling in longitudinal analyses (Li et al. 2014; Martinez et al. 2016; Siegmund and Shibata 2016) will continue to provide better insight into premalignant evolutionary trajectories with the goal of predicting the occurrence, pace, and prognosis of a future malignancy.

These temporal aspects of evolutionary events during carcinogenesis are also linked with the biological aging of human tissues (Finkel et al. 2007). By analyzing subclones within a neoplasm, one can build a “molecular clock” that considers genetic changes to occur at a constant rate; each new epi(genetic) mutation constitutes another “tick” of the clock, thus tracking biological age (Alexandrov et al. 2015). Molecular clocks have been constructed using methylation data to infer rates of clonal expansion and determine clonality in aging colonic adenomas (Yatabe et al. 2001; Graham et al. 2011; Humphries et al. 2013) and by tracing lineages of mitochondrial DNA mutated clones in prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) (Gaisa et al. 2011). Also, studies of both CpG island hypermethylation (Issa et al. 2001) and telomere shortening (Risques et al. 2008) in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) suggest that this premalignant condition exhibits accelerated or premature tissue aging during CRC progression. For asymptomatic premalignant conditions such as BE, constructing a molecular clock from DNA methylation data allows the quantification of epigenetic drift and thus the statistical inference of hidden clinical time points such as BE onset age (Curtius et al. 2016). Because chronological age is recognized as one of the strongest predictors of cancer risk, renewed attention has been given to exploring the roles of biological tissue age and cellular senescence in premalignant and neoplastic progression (Campisi 2013).

The mosaic patterns of genetically and epigenetically diverse clonal populations in premalignant tissues evolve in space as well as time (Tycko 2003; Leedham et al. 2008; Guo et al. 2015). How do these clones and subclones physically expand in a tissue? Tissue architecture constrains evolution by limiting the ability of mutant clones to expand, and so influences (lengthens) the waiting time to cancer (Martens et al. 2011). As provided in Table 1, premalignant epithelial clones expand within squamous tissue, such as epidermal, cervical, squamous oral, and esophagael mucosa by basal replacement of neighboring stem cells (Clayton et al. 2007; Klein et al. 2010; Doupé et al. 2012; Alcolea et al. 2014) or within glandular tissue via a process of crypt bifurcation termed crypt fission, such as that which occurs in intestinal metaplasia (IM) of the stomach and Barrett's esophagus (Greaves et al. 2006; McDonald et al. 2008; Nicholson et al. 2012). In these two different epithelia, clonal expansion involves different levels of selection: in squamous epithelium selection is acting at the level of individual cells, whereas in glands selection acts on the meta-population of the glands themselves. In squamous lesions, it is reasonable to believe that cells that are best able to adhere to the basement membrane will have increased survival and this phenotype will be positively selected. For glands, it is uncertain whether the ability to force crypt fission or the ability to survive environmental insult (such as acid/peptic digestion in the stomach) is the trait under selection (McDonald et al. 2015a). As in many ecological systems, there is likely an evolutionary trade-off occurring during phenotype selection—for example, increased proliferative potential at the expense of decreased offspring survival.

Architectural constraints during expansions affect both the size and types of premalignant clones that are positively selected for in a neoplasm. Clones compete for space in a complex process termed “clonal interference” (Garcia et al. 1999; Baker et al. 2013; Streichan et al. 2014; Greaves 2015). Because of minimal information on mutational event timing and spatial pervasiveness in past studies based on single time points (Maley et al. 2004), it is uncertain if mutant clone “sweeps to fixation” occur as a defining feature of premalignant disease. A recent “Big Bang” model of cancer formation illustrates the importance of timing of mutations during evolution as the determinant of a subclone’s pervasiveness in a neoplasm and the relatively rare opportunities for clonal sweeps to occur if at all (Sottoriva et al. 2015). Understanding the scales of units of selection, such as the time to fixation within stem cell niches within colonic and BE crypts, and the rate at which crypts divide, reveal important genetypic–phenotypic relationships in premalignant disease that constrain somatic evolution (Baker et al. 2014; McDonald et al. 2015a,b). From a clinical standpoint, measuring these physical scales of clonal architecture may help us to predict how many covert lesions are currently being missed during screening caused by imperfect tissue sampling (Reid et al. 2000; Whiting et al. 2002; Tschanz 2005), thus impacting our current interpretations of premalignant versus malignant prevalence that is currently estimated from epidemiological studies, and impacts our prognostication ability (Curtius et al. 2015; Dhawan et al. 2016).

MICROENVIRONMENT WITHIN PREMALIGNANT DISEASE

Tissue architecture and the premalignant microenvironment have a complex interrelationship, which plays a crucial role during natural selection and carcinogenesis. Microenvironmental changes such as fibroblast activation and modulation of the immune microenvironment (de Visser et al. 2006; Grivennikov et al. 2010; Elinav et al. 2013) may alter the fitness effects of (epi)genetic changes being introduced in lesions burdened with both driver and passenger mutations (Mbeunkui and Johann 2009). Microenvironmental pressures on tumor cell evolution can be both promoting (e.g., through the availability of growth factors or predation of inhibitory normal cells) and constraining (e.g., through preventing invasion by construction of an extracellular matrix). The microenvironment also regulates self-renewal in the epithelium (Davis et al. 2015). With respect to the genotype–phenotype map shown in Figure 1, microenvironmental factors act as natural selection pressures on phenotypes (arrow to point 2) that then (because of genetic mutation or phenotypic plasticity) explore the adaptive landscape such that genotypes of future generations reflect the phenotype that successfully surmounted any microenvironmental challenge that may be present (point 3). From this theoretical perspective, Gatenby and Gillies (2008) proposed a model to identify six such barriers, including hypoxia and acidosis in dysplastic epithelium, caused by the microenvironment that must be overcome throughout all stages of carcinogenesis. It is not simply a serendipitous match that a premalignant tissue is found in a particular ecosystem—clonal adaptation can only occur as a result of the current selective microenvironment.

Furthermore, premalignant microenvironments are not closed systems. Extrinsic environmental and lifestyle factors, such as exposure to cigarette carcinogens, dietary habits, and infections, can have a profound effect on the tissue ecosystem and dramatically influence carcinogenesis. For example, human papillomavirus (HPV) high-risk strains cause most cervical intraepithelial preinvasive lesions (Barron et al. 2014) and Helibacter pylori infection aids in the initiation of IM of the stomach (Yakirevich and Resnick 2013). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, which likely modulates the inflammatory microenvironment, was shown to reduce risk of progression to EAC in patients with BE by slowing clonal evolution via reducing the acquisition rate of somatic genetic alterations (Kostadinov et al. 2013). Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) increases the risk of BE progression to EAC, which is interestingly inversely related to EAC risk attributed to H. pylori infection (Anderson et al. 2008). Mathematical modeling of EAC progression suggests that age-dependent GERD symptoms can affect not only BE incidence but also proliferation rates of HGD during progression to EAC (Hazelton et al. 2015).

Recently, a study showed that the histological changes associated with GERD in esophageal tissue might be explained by a delayed inflammatory response prompted by secretion of cytokine proteins rather than immediate caustic injury caused by acid exposure (Dunbar et al. 2016). Immune cells of course play an important role in the premalignant microenvironment too. In patients with UC and Crohn’s disease, collectively called IBD, intestinal inflammation causes extensive ulceration from altered interactions between resident microbes and the bowel mucosa (Xavier and Podolsky 2007). IBD patients are at higher risk of CRC, and the severity of inflammation is an independent predictor of cancer risk (Rutter et al. 2004). As a final example, consistent changes in stromal gene expression and inflammatory pathways in precursor microenvironments have been found to co-occur across a variety of different gastrointestinal cancers (Saadi et al. 2010).

From an (epi)genetic standpoint, the preconditioning for cancer progression in a large area of tissue that resulted from a colonization of cells with a selected mutation, also known as “field cancerization,” may in fact be a common feature in epithelial carcinogenesis (Garcia et al. 1999; Baker et al. 2013). In both cancer progressors and nonprogressors, large, stable clones have been found that consist of cells with loss of heterozygosity (LOH) for chromosomes 9p and 17p in BE (Buas et al. 2014; Li et al. 2014) and those with distinct CpG island methylation signatures in colorectal adenomas (Luo et al. 2014.). As mentioned previously, a field effect caused by early common mutations in TP53 have also been found in BE segments (Stachler et al. 2015), and similarly in patients with UC (Leedham et al. 2009; Galandiuk et al. 2012) and lung cancer patients (Franklin et al. 1997; de Bruin et al. 2014; Pipinikas et al. 2014). Overall, the concept of monoclonal displacement of normal tissue in such a pervasive sense provokes important clinical questions whether antitumor treatments must aim to eliminate the entire clonal field of preneoplastic cells to prevent recurrence.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PROGNOSTICATION AND PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Characterizations and diagnoses of premalignant lesions have profound effects on cancer incidence and patient care. In particular, there has been an intensive effort to discover prognostic “biomarkers,” defined as measured attributes of a lesion that are associated with increased cancer risk, to aid in patient management (particularly to prevent overdiagnosis of cancer risk). Conventional pathologic grading/staging that describes tissue morphology remains the most common biomarker, and epidemiological studies provide estimates of annual subsequent cancer risk found among a patient population diagnosed with a certain premalignant state (see Table 1). These estimates can be low for early, mostly indolent premalignancies like nondysplastic BE (0.25% annual progression to adenocarcinoma) and typically increase for later stages, such as HGD within BE (∼6% annual progression) (Spechler 2013). However, for many premalignant phenotypes, there is large variability in published estimates of associated cancer risk, such as the range of 0.15% to 80% for annual risk of squamous carcinoma of the skin in patients with actinic keratosis (AK), caused by factors like interobserver variability, sampling bias, and patient cohort differences (Greaves 2014). In particular, interobserver variability is an issue for nearly every premalignant diagnosis and may differ at different stages of premalignancy (Fischer et al. 2004; Odze 2006; Leja et al. 2013; van den Einden et al. 2013; Osmond et al. 2014). For example, in a study by U.S. pathologists on BE, interobserver agreement was substantial for HGD and cancer (kappa agreement score, κ = 0.65), but was only fair (κ = 0.32) and then slight (κ = 0.15) for LGD and indefinite for dysplasia, respectively (Montgomery 2005). These results highlight the continuous nature of phenotype diagnoses, from normal appearing cells to slightly abnormal to more distinguishable neoplasms, and the difficulty in precisely identifying the “overlapping” features of phenotype space (Fig. 1) even by expert pathologists.

Because of the heterogeneous estimates of typically low rates involved in precancerous evolution, it is difficult to formulate effective surveillance schedules, that is, screen intervals for premalignant patients to have a checkup examination, which are simultaneously cost-effective, which avoid overdiagnosis/overtreatment, and that catch consequential lesions early. Most current guidelines suffer from ad hoc predictions based on mean progression rates seen in specific patient study cohorts that do not account for interindividual heterogeneity. Nonetheless, the primary goal of cancer screening has been to use this information to our advantage: if we look for and find cancer-risk signatures early in patients, we can reduce cancer mortality by performing an intervention, thus reducing the probability of malignancy arising in the future.

For precancers with long latent periods before cancer initiates, such as adenomas in the colon and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), screening and subsequent interventions are very effective and have substantially decreased colon and cervical cancer incidences (Barken et al. 2012; Zauber et al. 2012). In current public health policy, a more or less “one-size-fits-all” approach using population average risk estimates has been used in natural history Markov models to assess optimal screening ages and intervals to help inform screening guidelines (Winawer et al. 2006; de Koning et al. 2014). Additionally, other mathematical models for optimizing screening schedules take a more evolutionary approach by incorporating stochastic premalignant and malignant clonal expansions explicitly (Jeon et al. 2008; Hanin and Pavlova 2013; Curtius et al. 2015; Kroep et al. 2017). Although case-control studies aim to identify “who” benefits most from treatment during a set surveillance screen schedule, the goal of this modeling is to predict “when” and at what intervals should premalignant patients return to the clinic during follow-up. This relies on determining when (detectable) precursor lesions develop as we age and how long they dwell in a certain detectable disease state. Mathematical modeling of the stochastic evolutionary process can help to derive and to optimize the timing of clinical screens so that the probability is maximal that an individual is screened within a certain “window of opportunity” for intervention when early cancer development may be observed. By using the available estimates collected from epidemiological studies with long-term patient follow-up, in silico approaches aid in screening design and can perform useful cost-effectiveness analyses to compare proposed screening and intervention strategies.

In other cases, fast-growing premalignancies will be missed by screening (“underdiagnosis”) whereas patients found with slow-growing, or indolent, precursors undergo screening that suffers from length time bias (“overdiagnosis”) and thus will likely continue with costly surveillance programs until death by another cause (Esserman et al. 2013; Reid and Paulson 2015). In the case of breast cancer, a microsimulation model found that annual cost of mammographies in the United States to detect DCIS lesions and early cancers could be reduced by $8 billion, twice the annual budget of the NCI in 2014, if screening was performed biannually (as the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force now suggests) rather than annually (O’Donoghue et al. 2014). The balancing act between benefits and harms of screening can be difficult for a charged issue such as breast cancer screening, and is only complicated with the fact that issues of cost are less likely to be discussed between a physician and patient (Fox et al. 2012). Specifically, nearly all patients diagnosed with DCIS during a screen will undergo surgery followed by radiotherapy. Although a subset of 20% to 50% of those patients will progress to invasive breast cancer if left untreated (Cowell et al. 2013), the remaining patients will foster solely preinvasive phenotypes for their lifetimes. Thus, current medical recommendations seek to achieve a balance of cancer risk averted with compromised quality of life (e.g., owing to treatment costs and associated morbidities). Beyond screening for frank premalignant lesion existence, the long-term aim of cancer prevention is to “risk stratify” patients, that is, to accurately identify each patient as having low or high probability of progression to cancer—and at present the identification of premalignant phenotypes is the sole measure of risk. As per previous sections, we note that the definition of premalignant disease itself feeds into the debate of the goal of risk stratification—if all human cells are evolving to be more cancerized by the accumulation of somatic genetic alterations as we age, we are all part of the “at risk” population and thus further care must be taken in defining the premalignant prerequisites of having a consequential disease before administering certain treatments.

Beyond conventional pathologic staging, increasingly significant risk stratification is made possible based on additional morphological detail, such as premalignant lesion shape in colitis patients (Choi et al. 2015) and size (Anaparthy et al. 2013), and further still with the addition of genetic, epigenetic, and copy number markers correlated with malignant progression. A review by Kinzler and colleagues provides examples of recent studies that show the ability of genomic profiling to provide insight into premalignancy and application to cancer prevention (Kinzler et al. 2016). The idea that traditional markers such as dysplasia alone are sufficient to predict patient-specific risk is gradually becoming antiquated (Reid et al. 2010). Even a single genetic biomarker’s predictive power suffers from interobserver variability, as seen in a retrospective study of invasive breast cancers for precursor human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) amplification (Mamoon et al. 2014), and overdiagnosis, as was seen in the example that ubiquitous TP53 mutations are found in healthy skin yet few people will ever develop melanoma or basal cell carcinoma (Martincorena et al. 2015). Thus, satisfactory risk stratification may require a panel of biomarkers for each cancer type, and also further for each microenvironmental context and host-dependent setting, in order to increase sensitivity and specificity in determining which premalignancies are most probable to initiate malignancy. However, we again encounter the problem of correctly identifying the genotype–phenotype map (Fig. 1). Once patient-specific phenotypic, genotypic, microenvironmental, and clinical details are gathered at a screening time-point, we must predict the most probable future trajectory toward malignant phenotypes. How do we quantify if a patient’s phenotype and concurrent genotype determined at a screen is “approaching” a malignant phenotype?

As discussed in previous sections, tissue composition at all stages of carcinogenesis is extremely heterogeneous so one major limitation in current screening practice is sampling bias, and thus important premalignant clones may be missed. In effort to reconcile this problem, the analysis of tissue from multiple biopsies taken in a systematic way for use in both histology (Reid et al. 2000) and genetic analyses (Siegmund and Shibata 2016) helps in properly diagnosing pathologic grade and distinguishing between public (clonal) and private (subclonal) genetic mutations used in phylogenetic analyses. Furthermore, as discussed above, biomarkers based on quantifying the evolutionary process itself, such as measures of genetic diversity (Maley et al. 2006), may have pan-tissue prognostic value and be robust to spatial sampling (Dhawan et al. 2016).

In future designs of case-control studies, it seems likely that the most useful biomarker panel to assess patient-specific risk will be one that not only identifies worrisome phenotypes but also quantifies timescales and features of apparent premalignant evolution. Although we all accrue some cancer risk factors in our lifetime, three out of four of us will die of causes other than cancer. Thus, perhaps, the goal of risk stratification should be to identify patients with premalignant cells that are most quickly becoming closer to producing cancerous cells. This will require the analysis of an assemblage of patient-specific factors known to substantially increase cancer risk (e.g., genetic signatures including diversity, abnormal phenotypes, enabling microenvironments, biological rates of aging from molecular clocks) from, ideally, multiple serial time-points with adequate sampling to capture temporal and pervasive features. Additionally, the creation of observational registries regarding those patients who have indolent precancerous lesions (the “controls”) would benefit other patients with low-malignant potential to know more about the evolutionary dynamics of their disease (time-period for risk and type of cancer that may develop) to make informed decisions about treatment, including active surveillance strategies (Esserman et al. 2014). Readily available information produced by these studies for both doctor and patient can help to better identify high-malignant potential lesions (“cases”) while still combatting overdiagnosis by decreasing the number of surveillance screens and/or treatments undertaken by low-risk individuals (“controls”).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

How can we characterize premalignancy more precisely to understand the evolutionary process of carcinogenesis? As has been successfully completed for cancerous tumor types, an enticing initiative is to create a “Precancer Genome Atlas” (PCGA) by incorporating effort from multiple institutions worldwide to characterize the molecular alterations in premalignant lesions but importantly also the corresponding changes in the microenvironment and critically also the cellular phenotypes associated with progression to cancer (Campbell et al. 2016). As informative as the PCGA may be for precancer characterization, we have herein discussed the evidence that there is an abundance of gray areas in genotype and phenotype spaces; tissues diagnosed as cancerous, precancerous, and normal can share both genetic abnormalities and phenotypic traits. Because of the fact that cross-sectional studies of genetic alterations assayed at a single time point are insufficient to reliably infer important clonal evolution events over time, it will take concerted effort to understand the context-specific nature of cancer progression and the intricacies of the genotype–phenotype map by means of crucial longitudinal studies in the future. Thus, key issues in the evolution of cancer from premalignant disease include (1) determining temporal pattern of mutation accumulation in ostensibly normal tissue and premalignant disease, (2) teasing apart the role of microenvironment as an independent or concomitant driver of disease evolution, and (3) characterizing the host-specific attributes in general, including germline genetic history, immune system activity, microbiome, and other microenvironmental factors. Clearly, solutions to these would have tremendous value clinically as a basis for a prognostic test to evaluate cancer risk.

Do we all in fact develop precancerous clones as we age? Our current understanding of evolution suggests this is probable, as evidenced by a large autopsy study that found that as many as 15% of men with a “normal” prostate-specific antigen level (the placebo group) had prostate cancer (Thompson et al. 2004). If premalignant clones are indeed ubiquitous, perhaps the sheer mention of having “precancer” often causes undue fear followed by overly aggressive treatment of patients in current medical practice. Ultimately, multidisciplinary effort across pathology, imaging, surgical, computational biology, genetics, and medical communities has the ability to broaden and deepen our understanding of premalignant evolution and to ultimately reduce cancer mortality by more effectively managing patients identified as having premalignant disease. From an evolutionary standpoint, our current definition of what constitutes a premalignant cell (phenotype, [epi]genotype, and/or microenvironmental factors that incur cancer risk) must be revamped to be of greater clinical value because all cells in the body are increasingly becoming “closer to cancer” as we age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful for funding from the Barts and the London Charity and Cancer Research UK.

Footnotes

Editors: Charles Swanton, Alberto Bardelli, Kornelia Polyak, Sohrab Shah, and Trevor A. Graham

Additional Perspectives on Cancer Evolution available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Alcolea MP, Greulich P, Wabik A, Frede J, Simons BD, Jones PH. 2014. Differentiation imbalance in single oesophageal progenitor cells causes clonal immortalization and field change. Nat Cell Biol 16: 615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov LB, Jones PH, Wedge DC, Sale JE, Campbell PJ, Nik-Zainal S, Stratton MR. 2015. Clock-like mutational processes in human somatic cells. Nat Genet 47: 1402–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaparthy R, Gaddam S, Kanakadandi V, Alsop BR, Gupta N, Higbee AD, Wani SB, Singh M, Rastogi A, Bansal A, et al. 2013. Association between length of Barrett’s esophagus and risk of high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma in patients without dysplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11: 1430–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA, Murphy SJ, Johnston BT, Watson RG, Ferguson HR, Bamford KB, Ghazy A, McCarron P, McGuigan J, Reynolds JV, et al. 2008. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric atrophy and the stages of the oesophageal inflammation, metaplasia, adenocarcinoma sequence: Results from the FINBAR case-control study. Gut 57: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andor N, Graham TA, Jansen M, Xia LC, Aktipis CA, Petritsch C, Ji HP, Maley CC. 2016. Pan-cancer analysis of the extent and consequences of intratumor heterogeneity. Nature 22: 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, Loman N, Olsson H, Johannsson O, Borg Å, et al. 2003. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: A combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Gen 72: 1117–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulmann S, Elsawaf Z, Penzel R, Schirmacher P, Sinn HP. 2009. Invasive tubular carcinoma of the breast frequently is clonally related to flat epithelial atypia and low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Surg Pathol 33: 1646–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AM, Graham TA, Wright NA. 2013. Pre-tumour clones, periodic selection and clonal interference in the origin and progression of gastrointestinal cancer: Potential for biomarker development. J Pathol 229: 502–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AM, Cereser B, Melton S, Fletcher AG, Rodriguez-Justo M, Tadrous PJ, Humphries A, Elia G, McDonald SAC, Wright NA, et al. 2014. Quantification of crypt and stem cell evolution in the normal and neoplastic human colon. Cell Rep 8: 940–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barken SS, Rebolj M, Andersen ES, Lynge E. 2012. Frequency of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia treatment in a well-screened population. Int J Cancer 130: 2438–4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett MT, Sanchez CA, Prevo LJ, Wong DJ, Galipeau PC, Paulson TG, Rabinovitch PS, Reid BJ. 1999. Evolution of neoplastic cell lineages in Barrett oesophagus. Nature Gen 22: 106–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron S, Li Z, Austin RM, Zhao C. 2014. Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion/cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL-H) is a unique category of cytologic abnormality associated with distinctive HPV and histopathologic CIN 2+ detection rates. Am J Clin Pathol 141: 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfey PN, Mitchell-Olds T. 2008. From genotype to phenotype: Systems biology meets natural variation. Science 320: 495–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Simons BD. 2013. Unravelling stem cell dynamics by lineage tracing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 14: 489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick DG, Cheng L. 2012. Precursors of prostate cancer. Histopathology 60: 4–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botstein D, Risch N. 2003. Discovering genotypes underlying human phenotypes: Past successes for Mendelian disease, future approaches for complex disease. Nature Gen 33: 228–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buas MF, Levine DM, Makar KW, Utsugi H, Onstad L, Li X, Galipeau PC, Shaheen NJ, Hardie LJ, Romero Y, et al. 2014. Integrative post-genome-wide association analysis of CDKN2A and TP53 SNPs and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis 35: 2740–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd EM. 2003. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev 16: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese P, Tavaré S, Shibata D. 2004. Pretumor progression: Clonal evolution of human stem cell populations. Am J Pathol 164: 1337–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Mazzilli SA, Reid ME, Dhillon SS, Platero S, Beane J, Spira AE. 2016. The case for a pre-cancer genome atlas (PCGA). Cancer Prev Res 9: 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. 2013. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol 75: 685–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler CH, Chari S, Dworkin I. 2013. Does your gene need a background check? How genetic background impacts the analysis of mutations, genes, and evolution. Trends Genet 29: 358–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanock SJ, Manolio T, Boehnke M, Boerwinkle E, Hunter DJ, Thomas G, Hirschhorn JN, Abecasis G, Altshuler D, Bailey-Wilson JE, et al. 2007. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature 447: 655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi CH, Ignjatovic-Wilson A, Askari A, Lee GH, Warusavitarne J, Moorghen M, Thomas-Gibson S, Saunders BP, Rutter MD, Graham TA, et al. 2015. Low-grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis: Risk factors for developing high-grade dysplasia or colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 110: 1461–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton E, Doupé DP, Klein AM, Winton DJ, Simons BD, Jones PH. 2007. A single type of progenitor cell maintains normal epidermis. Nature 446: 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole K, Tabemero M, Anderson KS. 2010. Biologic characteristics of premalignant breast disease. Cancer Biomark 9: 177–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coradini D, Oriana S. 2014. Breast cancer precursors: Perturbations of mammary epithelial cell Identity as a response to abnormal signaling from stromal compartment. Cancer Cell Microenvir 1: e239. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell CF, Weigelt B, Sakr RA, Ng CK, Hicks J, King TA, Reis-Filho JS. 2013. Progression from ductal carcinoma in situ to invasive breast cancer: Revisited. Mol Oncol 7: 859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross W, Graham TA, Wright NA. 2016. New paradigms in clonal evolution: Punctuated equilibrium in cancer. J Pathol 240: 126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtius K, Hazelton W, Jeon J, Luebeck E. 2015. A multiscale model evaluates screening for neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. PLoS Comput Biol 11: e1004272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtius K, Wong C, Hazelton WD, Kaz AM, Chak A, Willis JE, Grady WM, Luebeck EG. 2016. A molecular clock infers heterogeneous tissue age among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. PLoS Comput Biol 12: e1004914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curvers WL, Ten Kate FJ, Krishnadath KK, Visser M, Elzer B, Baak LC, Bohmer C, Mallant-Hent RC, Van Oijen A, Naber AH, et al. 2010. Low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: Overdiagnosed and underestimated. Am J Gastroenterol 105: 1523–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H, Irshad S, Bansal M, Rafferty H, Boitsova T, Bardella C, Jaeger E, Lewis A, Freeman-Mills L, Giner FC, et al. 2015. Aberrant epithelial GREM1 expression initiates colonic tumorigenesis from cells outside the stem cell niche. Nat Med 21: 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin EC, McGranahan N, Mitter R, Salm M, Wedge DC, Ytes L, Jamal-Hanjani M, Shafi S, Murugaesu N, Rowan AJ, et al. 2014. Spatial and temporal diversity in genomic instability processes defines lung cancer evolution. Science 346: 251–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, Ten Haaf K, Munshi VN, Jeon J, Erdogan SA, Kong CY, Han SS, van Rosmalen J, et al. 2014. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: A comparative modeling study for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 160: 311–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. 2006. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 6: 24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan A, Graham TA, Fletcher AG. 2016. A computational modeling approach for deriving biomarkers to predict cancer risk in premalignant disease. Cancer Prev Res 9: 283–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupé DP, Alcolea MP, Roshan A, Zhang G, Klein AM, Simons BD, Jones PH. 2012. A single progenitor population switches behavior to maintain and repair esophageal epithelium. Science 337: 1091–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar KB, Agoston AT, Odze RD, Huo X, Pham TH, Cipher DJ, Castell DO, Genta RM, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. 2016. Association of acute gastroesophageal reflux disease with esophageal histologic changes. JAMA 315: 2104–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echenique I, Phillips BR. 2011. Anal warts and anal intradermal neoplasia. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 24: 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav E, Nowarski R, Thaiss CA, Hu B, Jin C, Flavell RA. 2013. Inflammation-induced cancer: Crosstalk between tumours, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer 13: 759–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman L, Yau C. 2015. Rethinking the standard for ductal carcinoma in situ treatment. JAMA Oncol 1: 881–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman LJ, Thompson IM Jr, Reid B. 2013. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: An opportunity for improvement. J Am Med Assoc 310: 797–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B, Nelson P, Ransohoff DF, Welch HG, Hwang S, Berry DA, Kinzler KW, Black WC, et al. 2014. Addressing overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: A prescription for change. Lancet Oncol 15: e234–e242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, Koldobskiy MA, Göndör A. 2016. Epigenetic modulators, modifiers, and mediators in cancer aetiology and progression. Nat Rev Genet 17: 284–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T, Serrano M, Blasco MA. 2007. The common biology of cancer and ageing. Nature 448: 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DJ, Epstein JB, Morton TH, Schwartz SM. 2004. Interobserver reliability in the histopathologic diagnosis of oral pre-malignant and malignant lesions. J Oral Pathol Med 33: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald RC. 2010. Pre-invasive disease: Pathogenesis and clinical management. Springer Science & Business Media, London. [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Gross CP. 2012. Older patient experiences in the mammography decision-making process. Arch Intern Med 172: 62–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin WA, Gazdar AF, Haney J, Wistuba II, La Rosa FG, Kennedy T, Ritchey DM, Miller YE. 1997. Widely dispersed p53 mutation in respiratory epithelium. A novel mechanism for field carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest 100: 2133–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagneur J, Stegle O, Zhu C, Jakob P, Tekkedil MM, Aiyar RS, Schuon AK, Pe’er D, Steinmetz LM. 2013. Genotype-environment interactions reveal causal pathways that mediate genetic effects on phenotype. PLoS Genet 9: e1003803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaisa NT, Graham TA, McDonald SA, Poulsom R, Heidenreich A, Jakse G, Knuechel R, Wright NA. 2011. Clonal architecture of human prostatic epithelium in benign and malignant conditions. J Pathol 225: 172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galandiuk S, Rodriguez-Justo M, Jeffery R, Nicholson AM, Cheng Y, Oukrif D, Elia G, Leedham SJ, McDonald SA, Wright NA, Graham TA. 2012. Field cancerization in the intestinal epithelium of patients with Crohn’s ileocolitis. Gastroenterology 142: 855–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia SB, Park HS, Novelli M, Wright NA. 1999. Field cancerization, clonality, and epithelial stem cells: The spread of mutated clones in epithelial sheets. J Pathol 187: 61–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. 2008. A microenvironmental model of carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, Lindberg J, Rose SA, Bakhoum SF, Chambert K, Mick E, Neale BM, Fromer M, et al. 2014. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. New Engl J Med 371: 2477–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordetsky J, Epstein JI. 2015. Intestinal metaplasia of the bladder with dysplasia: A risk factor for carcinoma? Histopathology 67: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TA, McDonald SAC. 2010. Genetic diversity during the development of Barrett’s oesophagus-associated adenocarcinoma: How, when and why? Biochem Soc Trans 38: 374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TA, Humphries A, Sanders T, Rodriguez-Justo M, Tadrous PJ, Preston SL, Novelli MR, Leedham SJ, McDonald SAC, Wright NA. 2011. Use of methylation patterns to determine expansion of stem cell clones in human colon tissue. Gastroenterology 140: 1241–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves M. 2014. Does everyone develop covert cancer? Nat Rev Cancer 14: 209–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves M. 2015. Evolutionary determinants of cancer. Cancer Discovery 5: 806–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves M, Maley CC. 2012. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature 481: 306–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves MF, Maia AT, Wiemels JL, Ford AM. 2003. Leukemia in twins: Lessons in natural history. Blood 102: 2321–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves LC, Preston SL, Tadrous PJ, Taylor RW, Barron MJ, Oukrif D, Leedham SJ, Deheragoda M, Sasieni P, Novelli MR, et al. 2006. Mitochondrial DNA mutations are established in human colonic stem cells, and mutated clones expand by crypt fission. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 714–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. 2010. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140: 883–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Zhou J, Huang A, Li J, Yan M, Zhu Z, Zhao X, Gu J, Liu B, Shao Z. 2015. Spatially defined microsatellite analysis reveals extensive genetic mosaicism and clonal complexity in intestinal metaplastic glands. Int J Cancer 126: 2973–2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144: 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanin L, Pavlova L. 2013. Optimal screening schedules for prevention of metastatic cancer. Stat Med 32: 206–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann LC, Degnim AC, Santen RJ, Dupont WD, Ghosh K. 2015. Atypical hyperplasia of the breast—Risk assessment and management options. N Engl J Med 372: 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazelton WD, Curtius K, Inadomi JM, Vaughan TL, Meza R, Rubenstein JH, Hur C, Luebeck EG. 2015. The role of gastroesophageal reflux and other factors during progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidem Biomar 24: 1012–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstad B, Vatn MH, Andersen SN, Huitfeldt HS, Rognum T, Larsen S, Osnes M. 1996. Growth of colorectal polyps: Redetection and evaluation of unresected polyps for a period of three years. Gut 39: 449–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle D, Govindaraju DR, Omholt S. 2010. Phenomics: The next challenge. Nat Rev Genet 11: 855–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruban RH, Fukushima N. 2007. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Update on the surgical pathology of carcinomas of ductal origin and PanINs. Modern Pathol 20: S61–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries A, Ceresar B, Gay LJ, Miller DSJ, Das B, Gutteridge A, Elia G, Nye E, Jeffery R, Poulsom R, et al. 2013. Lineage tracing reveals multipotent stem cells maintain human adenomas and the pattern of clonal expansion in tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: E2490–E2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. 2012. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: An independent review. Lancet 380: 1778–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JPJ, Ahuja N, Toyota M, Bronner MP, Brentnall TA. 2001. Accelerated age-related CpG island methylation in ulcerative colitis. Cancer Res 61: 3573–3577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawad N, Direkze N, Leedham SJ. 2011. Inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res 185: 99–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon J, Meza R, Moolgavkar SH, Luebeck EG. 2008. Evaluation of screening strategies for pre-malignant lesions using a biomathematical approach. Math Biosci 213: 56–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Lippman SM, Flaherty KT, Kurzrock R. 2016. The conundrum of genetic “drivers” in benign conditions. J Natl Cancer I 108: djw036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaz AM, Grady WM, Stachler MD, Bass AJ. 2015. Genetic and epigenetic alterations in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 44: 473–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhof M, Van Dekken H, Steyerberg EW, Meijer GA, Mulder AH, De Bruïne A, Driessen A, Ten Kate FJ, Kusters JG, Kuipers EJ, et al. 2007. Grading of dysplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus: Substantial interobserver variation between general and gastrointestinal pathologists. Histopathology 50: 920–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler TW, Spira A, Garber JE, Szabo E, Lee JJ, Dong Z, Dannenberg AJ, Hait WN, Blackburn E, Davidson NE, et al. 2016. Transforming cancer prevention through precision medicine and immune-oncology. Cancer Prev Res 9: 2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AM, Simons BD. 2011. Universal patterns of stem cell fate in cycling adult tissues. Development 138: 3103–3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AM, Brash DE, Jones PH, Simons BD. 2010. Stochastic fate of p53-mutant epidermal progenitor cells is tilted toward proliferation by UV B during preneoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson AG. 1971. Mutation and cancer: Statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci 68: 820–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostadinov RL, Kuhner MK, Li X, Sanchez CA, Galipeau PC, Paulson TG, Sather CL, Srivastava A, Odze RD, Blount PL, et al. 2013. NSAIDs modulate clonal evolution in Barrett’s esophagus. PLoS Genet 9: e1003553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroep S, Heberle CR, Curtius K, Kong CY, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Ali A, Wolf WA, Shaheen NJ, Spechler SJ, Rubenstein JH, et al. 2017. Impact of radiofrequency ablation treatment of Barrett’s Esophagus on eosphageal adenocarcinoma: A comparative modeling analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryvenko ON, Jankowski M, Chitale DA, Tang D, Rundle A, Trudeau S, Rybicki BA. 2012. Inflammation and preneoplastic lesions in benign prostate as risk factors for prostate cancer. Modern Pathol 25: 1023–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurman RJ, Shih IM. 2010. The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer––A proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol 34: 433–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Mermel CH, Robinson JT, Garraway LA, Golub TR, Meyerson M, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Getz G. 2014. Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature 505: 495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leedham SJ, Preston SL, McDonald SA, Elia G, Bhandari P, Poller D, Harrison R, Novelli MR, Jankowski JA, Wright NA. 2008. Individual crypt genetic heterogeneity and the origin of metaplastic glandular epithelium in human Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 57: 1041–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leedham SJ, Graham TA, Oukrif D, McDonald SA, Rodriguez-Justo M, Harrison RF, Shepherd NA, Novelli MR, Jankowski JA, Wright NA. 2009. Clonality, founder mutations, and field cancerization in human ulcerative colitis-associated neoplasia. Gastroenterology 136: 542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leja M, Funka K, Janciauskas D, Putnins V, Ruskule A, Kikuste I, Kojalo U, Tolmanis I, Misins J, Purmalis K, et al. 2013. Interobserver variation in assessment of gastric premalignant lesions: Higher agreement for intestinal metaplasia than for atrophy. Eur J Gastroen Hepat 25: 694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Galipeau PC, Paulson TG, Sanchez CA, Arnaudo J, Liu K, Sather CL, Kostadinov RL, Odze RD, Kuhner MK, et al. 2014. Temporal and spatial evolution of somatic chromosomal alterations: A case-cohort study of Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Prev Res 7: 114–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Beltran A, Montironi R, Vidal A, Scarpelli M, Cheng L. 2013. Urothelial dysplasia of the bladder: Diagnostic features and clinical significance. Anal Quant Cytopathol Histpathol 35: 121–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Wong CJ, Kaz AM, Dzieciatkowski S, Carter KT, Morris SM, Wang J, Willis JE, Makar KW, Ulrich CM, et al. 2014. Differences in DNA methylation signatures reveal multiple pathways of progression from adenoma to colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 147: 418–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maley CC, Galipeau PC, Li X, Sanchez CA, Paulson TG, Reid BJ. 2004. Selectively advantageous mutations and hitchhikers in neoplasms p16 lesions are selected in Barrett’s Esophagus. Cancer Res 64: 3414–3427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maley CC, Galipeau PC, Finley JC, Wongsurawat VJ, Li X, Sanchez CA, Paulson TG, Blount PL, Risques RA, Rabinovitch PS, et al. 2006. Genetic clonal diversity predicts progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet 38: 468–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamoon N, Syed FN, Mushtaq S, Nasir H, Ahmad IN. 2014. Interobserver variability in HER-2/neu reporting on immunohistochemistry in breast carcinomas. J Pak Med Assoc 64: 151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens EA, Kostadinov R, Maley CC, Hallatschek O. 2011. Spatial structure increases the waiting time for cancer. New J Phys 13: 115014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martincorena I, Roshan A, Gerstung M, Ellis P, Van Loo P, McLaren S, Wedge DC, Fullam A, Alexandrov LB, Tubio JM, et al. 2015. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science 348: 880–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez P, Timmer MR, Lau CT, Calpe S, Sancho-Serra MDC, Straub D, Baker A, Meijer SL, ten Kate FJW, Mallant-Hent RC, et al. 2016. Longitudinal single cell analysis reveals evolutionary stasis and predetermined malignant potential in non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus. Nature Comm 7: 12158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbeunkui F, Johann DJ Jr. 2009. Cancer and the tumor microenvironment: A review of an essential relationship. Cancer Chemoth Pharm 63: 571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SA, Greaves LC, Gutierrez–Gonzalez L, Rodriguez–Justo M, Deheragoda M, Leedham SJ, Taylor RW, Lee CY, Preston SL, Lovell M, et al. 2008. Mechanisms of field cancerization in the human stomach: The expansion and spread of mutated gastric stem cells. Gastroenterology 134: 500–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]