This study assesses the association of dissemination of an educational document about the lack of efficacy of docusate with docusate administration and whether changes in docusate administration were associated with changes in the administration of comparable laxatives.

Key Points

Question

How is docusate administration affected when clinicians are presented with a message to discontinue its use?

Findings

This quasi-experimental pre-post study among Alberta Health Services facilities in Alberta, Canada, found a 54.9% relative reduction in docusate administration at 18 months after intervention, with no significant change in select comparable laxative administration.

Meaning

A concise message, with a clear call to action, can significantly decrease the clinician administration of a medication that has limited efficacy.

Abstract

Importance

A clear message and call to action can affect the use of a medication with limited efficacy.

Objectives

To assess the association of the dissemination of an educational document about the lack of efficacy of docusate with docusate administration and whether changing docusate administration was associated with a change in administration of comparable laxatives.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this quasi-experimental, pre-post study of all acute care and continuing care facilities serviced by Alberta Health Services in Alberta, Canada, an interrupted time series analysis was performed to examine the association of an educational communication tool with docusate administration from June 1, 2014, through May 31, 2016.

Interventions

A Drugs & Therapeutics Backgrounder was disseminated to all pharmacists in December 2014. Backgrounders are academic detailing tools to assist pharmacists in supporting drug stewardship and are supplemented by online, interactive webinars.

Main Outcomes and Measures

This study examined whether a decrease in docusate administration across the organization occurred after release of the backgrounder. Messaging in the backgrounder stated that, unless clinically necessary, docusate should not be replaced by another medication. This study assessed whether that message was accepted by measuring administration of comparable laxatives. Study medication administration is reported as defined daily doses (DDDs) per 1000 inpatient-days (PDs). Rates were compared for the 6 months before the intervention and 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after intervention.

Results

Among the 111 acute care facilities (8500 beds) and 24 000 long-term care beds of the Alberta Health Services, predicted docusate administration decreased from preintervention (474 DDDs/1000 PDs) to 3 months (321 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 304-465 DDDs/1000 PDs), 6 months (296 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 277-456 DDDs/1000 PDs), 12 months (251 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 207-499 DDDs/1000 PDs), and 18 months (214 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 148-536 DDDs/1000 PDs). Administration of the comparable laxatives did not statistically significantly change (preintervention: 627 DDDs/1000 PDs; 18 months after intervention: 702 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 295-694 DDDs/1000 PDs; P = .13).

Conclusions and Relevance

A communication document supported by live presentations was associated with decreased administration of docusate up to 6 months, with a leveling of the association after 1 year. Significant systemic change can be achieved without extensive and complex interventions if the evidence and messaging are aligned.

Introduction

Preventing and/or treating constipation in patients is a common concern for clinicians. Up to 43% of inpatients experience constipation within the first 3 days of hospital admission. Constipation increases discomfort and may lead to abdominal cramping and straining on defecation that ultimately affect quality of life.

Docusate is an over-the-counter medication classified as a stool softener that is primarily used to prevent constipation and is commonly prescribed in the community and hospital settings. Docusate acts as an emollient and surfactant to emulsify stool and is marketed to aid in the passage of hardened stool.

The efficacy of docusate in the prevention of constipation has been questioned in several studies and review articles, including a systematic review that concluded that docusate appears to be no more effective than placebo. Docusate did not lessen symptoms associated with constipation (ie, abdominal cramps) or affect the perceptions associated with completeness of or difficulties with stool evacuation. Although the quality of studies is generally poor and the patients studied were not generalizable to all patients with constipation, it can be concluded that docusate is not beneficial in the prevention of constipation.

In general, laxatives (and especially docusate) are inexpensive to purchase. However, because of their volume of administration, the systemwide indirect costs are substantial, involving pharmacy procurement and distribution, nursing administration, and patient pill burden. Lee et al found that, in their facility, docusate accounted for 64% of total laxative administration, and 50% of patients were discharged with prescriptions for the medication, extending pill burden and costs into the community.

Continued administration of docusate despite its documented lack of efficacy is driven by several factors, including inexpensive individual procurement costs, historical and long-standing administration, apathy toward intervening on a perceived innocuous substance, ongoing inclusion in textbooks and guidelines, and potential complexity in changing practice. Initial discussions with stakeholders in our organization indicated the need for a straightforward approach that would not administratively burden frontline staff. As a result, a phased approach to reducing docusate administration was used, beginning with broad education.

Alberta Health Services (AHS) Pharmacy Services regularly publishes Drugs & Therapeutics Backgrounders, which are academic detailing tools that briefly summarize evidence about the safety, efficacy, and sustainability of medications. Pharmacists use these to supplement therapeutic conversations with prescribers. In December 2014, Stool Softeners: WHY Are They Still Used? was published. It describes the evidence for lack of efficacy of docusate and includes a clear call to action that docusate use can be discontinued safely and, unless clinically necessary, not be replaced with another medication. Pharmacists are not directed to use the backgrounder in a specific manner but encouraged to use the information in interactions with prescribers, nurses, and patients to avoid or discontinue the use of docusate. The backgrounder was supported by 2 interactive webinars in which the author provided context and answered any questions from the audience. We hypothesized that a straightforward, multimodal communication process with messaging and a call to action would reduce the amount of docusate dispensed and would not result in subsequent increases in the administration of comparable laxative medications.

Methods

We conducted an uncontrolled pre-post study in AHS. Alberta is a Canadian province with 4.2 million individuals, and all Albertans are provided publicly funded health coverage through the Canada Health Act. Alberta Health Services and its affiliated organizations are responsible for health care delivery at 106 acute care hospitals, 5 psychiatric facilities, and 24 000 continuing care beds, which were included in this study. We used Alberta Innovates’ Project Ethics Community Consensus Initiative ethics guidelines for quality improvement and evaluation projects to guide this study. The Project Ethics Community Consensus Initiative Ethics Screening Tool assessed the ethical risk of this quality improvement initiative to be minimal risk, and review by a research ethics board was not deemed to be necessary.

The primary objective was to determine the association of the backgrounder with the administration of docusate in inpatients and nursing home residents for a period of 18 months after the intervention. As a secondary objective, we assessed whether there was an association of the change in docusate administration with the administration of comparable laxative medications with mechanisms of action that improve the pliability of stool. Stimulant laxatives (eg, senna, bisacodyl) were excluded because their mechanism of action differs greatly from that of the study medications.

Quantities of study medications (docusate, polyethylene glycol 3350, lactulose, magnesium hydroxide, and psyllium) dispensed to inpatients and nursing home residents each month were obtained from pharmacy dispensing systems used in AHS (MediTech, Medical Information Technology Inc, BDM, BDM IT Solutions Inc, Centricity, and HE Healthcare) from June 1, 2014, through May 31, 2016. These data were converted to defined daily doses (DDDs) and standardized for bed use by dividing by 1000 inpatient-days (PDs) (Table 1). Docusate expenditures were obtained from AHS Pharmacy Services Procurement and Inventory.

Table 1. Defined Daily Dose (DDD) Conversions for Study Medications.

| Medication | DDD |

|---|---|

| Docusate calciuma | 360mg |

| Docusate sodiuma | 150mg |

| Lactulosea | 6.7g |

| Magnesium hydroxidea | 3g |

| Polyethylene glycol 3350 powderb | 17g |

| Psylliumb | 7g |

According to the World Health Organization.

According to the Canadian Pharmacists Association.

Changes in DDDs per 1000 PDs for docusate and the composite of comparable laxatives during the baseline period were compared by interrupted time series analysis to rates at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months after the intervention. SPSS statistical software, version 19 (IBM Inc) was used for autoregressive integrated moving average analysis and applied interrupted time series techniques described by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group.Autoregressive integrated moving average analysis was used to calculate P values, with a 1-sided significance level of P < .05.

Results

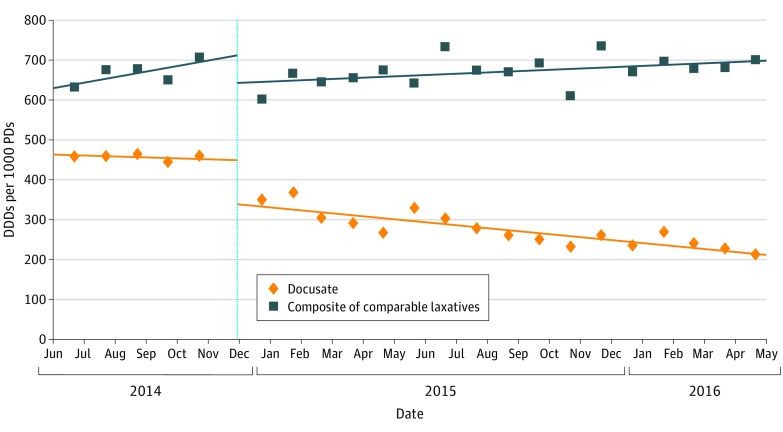

In the 6 months before backgrounder dissemination, the administration of docusate was stable at 474 DDDs/1000 PDs and the administration of the composite of comparable laxatives was stable at 627 DDDs/1000 PDs (Figure and Table 2). After the intervention, predicted docusate administration decreased to 321 DDDs/1000 PDs (95% CI, 304-465 DDDs/1000 PDs) at 3 months, 296 DDDs/1000 PDs (95% CI, 277-456 DDDs/1000 PDs) at 6 months, 251 DDDs/1000 PDs (95% CI, 207-499 DDDs/1000 PDs) at 12 months, and 215 DDDs/1000 PDs (95% CI, 148-536 DDDs/1000 PDs) at 18 months (Table 2). Total docusate DDDs dispensed decreased by approximately 50 000 per month from the predissemination period to the 18 months after dissemination. The composite of comparable laxative medications dipensed did not statistically significantly change from the baseline (627 DDDs/1000 PDs) to the postintervention period, with 95% CIs at all observation points not contained below unity (3 months: 646 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 483-639 DDDs/1000 PDs; P = .06; 6 months: 656 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 460-645 DDDs/1000 PDs; P = .07; 12 months: 710 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 371-671 DDDs/1000 PDs; P = .11; 18 months: 702 DDDs/1000 PDs; 95% CI, 295-694 DDDs/1000 PDs; P = .13) (Table 2).

Figure. Define Daily Doses (DDDs) of Docusate and Comparable Laxative Medications Dispensed per 1000 Inpatient-days (PDs).

Table 2. Administration of Docusate and Composite of Alternative Medications.

| Drug, Time Point | Actual Administration, DDDs/1000 PDs | Predicted Administration, DDDs/1000 PDs (95% CI) | Predicted Relative Change From Baseline, % | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docusate | ||||

| Before dissemination | 458 | 474 (462-482) | NA | .60 |

| 3 mo | 304 | 321 (304-465) | −21.8 | .02 |

| 6 mo | 328 | 296 (277-456) | −37.5 | .01 |

| 12 mo | 259 | 251 (207-499) | −47.0 | .06 |

| 18 mo | 212 | 215 (148-536) | −54.9 | .12 |

| Composite of Alternative Medications | ||||

| Before dissemination | 660 | 627 (612-632) | NA | .23 |

| 3 mo | 645 | 646 (483-639) | 3.0 | .06 |

| 6 mo | 641 | 656 (460-645) | 4.6 | .07 |

| 12 mo | 734 | 710 (371-671) | 13.2 | .11 |

| 18 mo | 699 | 702 (295-694) | 12.0 | .13 |

Abbreviations: DDDs, defined daily doses; NA, not applicable; PD, inpatient-days.

Discussion

Administration of docusate for constipation prevention is not supported by published evidence, although it remains a considerable driver of health care resource use. The blended communication method that we used conveyed the backgrounder messages effectively and was associated with a decrease in docusate administration by more than half in the 18 months after dissemination of the backgrounder and the webinar sessions.

Observations at 3 and 6 months exceeded the threshold established for downward trends greater than in the baseline period. Although the 95% CIs at 12 and 18 months were not contained below unity, this would indicate a flattening of the rate of decrease. Slowing of the rate of decrease is expected during an extended follow-up period, when no further reminders are provided.

The composite of comparable laxative medications did not change correspondingly, with 95% CIs crossing zero at all study intervals. This finding indicates that docusate was not being replaced with more expensive alternatives.

Pharmacoeconomic analysis was not an objective of this study but warrants discussion. Annual docusate purchases were approximately $100 000 before the intervention and $30 000 at the conclusion, representing a small fraction of AHS’s total drug budget. Lee et al used an estimate of 45 seconds as the time required for a nurse to administer a dose of medication. At the conclusion of the study period, approximately 50 000 fewer docusate DDDs (75 000 × 100-mg doses) were dispensed across the organization per month than at the beginning of the study, which would equal approximately 940 hours of nursing time. We acknowledge that shifting workload in this manner does not result in monetary savings for the organization, but it cumulatively improves time efficiency, which benefits patient care.

Limitations

Because of the limitation of the current pharmacy dispensing systems, we could not account for wasted and expired medication or administration for other indications. We also could not rule out the effect of external influences on pharmacists and prescriber's perceptions about docusate administration.

Conclusions

A straightforward communication tool supported by live question-and-answer sessions was associated with decreased docusate administration across our organization. This study was an important first step in the eventual removal of docusate from the formulary, which is anticipated to occur in 2017. Furthermore, this type of intervention could be generalized to reduce the administration of other high-use, low-value medications if the evidence and messages align.

References

- 1.Noiesen E, Trosborg I, Bager L, Herning M, Lyngby C, Konradsen H. Constipation: prevalence and incidence among medical patients acutely admitted to hospital with a medical condition. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(15-16):2295-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tack J, Müller-Lissner S, Stanghellini V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation: a European perspective. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23(8):697-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dynamed. Docusate Monograph. http://www.dynamed.com. Accessed July 17, 2015.

- 4.Castle SC, Cantrell M, Israel DS, Samuelson MJ. Constipation prevention: empiric use of stool softeners questioned. Geriatrics. 1991;46(11):84-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramkumar D, Rao SSC, Ph D. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):936-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hurdon V, Viola R, Schroder C. How useful is docusate in patients at risk for constipation? A systematic review of the evidence in the chronically ill. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(2):130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health Dioctyl Sulfosuccinate or Docusate (Calcium or Sodium) for the Prevention or Management of Constipation: A Review of the Clinical Effectiveness. CADTH Rapid Response Reports. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee TC, McDonald EG, Bonnici A, Tamblyn R. Pattern of inpatient laxative use: waste not, want not. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1216-1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasay D. Stool Softeners: WHY Are They Still Used? Drugs and Therapeutics Backgrounder 2014. http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/pharm/if-hp-pharm-docusate-delisting-backgrounder.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2015.

- 10.Government of Canada Canada Health Act [Loi canadienne sur la santé]. 1984, c 6, s 1.

- 11.Alberta Health Services - Who We Are. http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/about/about.aspx. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- 12.Health Research Ethics Board of Alberta A Project Ethics Community Consensus Initiative (ARECCI) Ethics Guidelines for Quality Improvement and Evaluation Projects. http://www.aihealthsolutions.ca/arecci/guidelines/. Accessed July 17, 2015.

- 13.Health Research Ethics Board of Alberta A Project Ethics Community Consensus Initiative (ARECCI) Screening Tool. http://www.aihealthsolutions.ca/arecci/screening/. Accessed July 17, 2015.

- 14.World Health Organization Define Daily Dose: Definition and General Considerations. https://www.whocc.no/ddd/definition_and_general_considera/. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- 15.Canadian Pharmacists Association Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties (CPS). https://www.pharmacists.ca/products-services/compendium-of-pharmaceuticals-and-specialties/. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- 16.Ramsay CR, Matowe L, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19(4):613-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flodgren G, Oddgard-Jensen J. Interrupted time series (ITS) analyses. PLoS One. 2013;13(April):1-13. [Google Scholar]