This study examines the association of higher patient cost sharing with mental health care use and downstream effects, such as involuntary commitment and acute mental health care use.

Key Points

Questions

Does higher patient cost sharing for mental health care reduce use and, if so, increase downstream costs to the patient or society?

Findings

This study of 1 448 541 treatment records in the Netherlands found that a national reform that increased cost sharing led to reduced use of mental health care for severe and mild disorders, especially in low-income neighborhoods. Overall, this reduced use created net savings, but for patients with psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder, the reform was associated with costly increases in involuntary commitment and acute mental health care.

Meaning

Higher cost sharing for seriously ill patients could create substantial downstream costs.

Abstract

Importance

A higher out-of-pocket price for mental health care may lead not only to cost savings but also to negative downstream consequences.

Objective

To examine the association of higher patient cost sharing with mental health care use and downstream effects, such as involuntary commitment and acute mental health care use.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This difference-in-differences study compared changes in mental health care use by adults, who experienced an increase in cost sharing, with changes in youths, who did not experience the increase and thus formed a control group. The study examined all 2 780 558 treatment records opened from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2012, by 110 organizations that provide specialist mental health care in the Netherlands. Data analysis was performed from January 18, 2016, to May 9, 2017.

Exposures

On January 1, 2012, the Dutch national government increased the out-of-pocket price of mental health services for adults by up to €200 (US$226) per year for outpatient treatment and €150 (US$169) per month for inpatient treatment.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The number of treatment records opened each day in regular specialist mental health care, involuntary commitment, and acute mental health care, and annual specialist mental health care spending.

Results

This study included 1 448 541 treatment records opened from 2010 to 2012 (mean [SD] age, 41.4 [16.7] years; 712 999 men and 735 542 women). The number of regular mental health care records opened for adults decreased abruptly and persistently by 13.4% (95% CI, −16.0% to −10.8%; P < .001) per day when cost sharing was increased in 2012. The decrease was substantial and significant for severe and mild disorders and larger in low-income than in high-income neighborhoods. Simultaneously, in 2012, daily record openings increased for involuntary commitment by 96.8% (95% CI, 87.7%-105.9%; P < .001) and for acute mental health care by 25.1% (95% CI, 20.8%-29.4%; P < .001). In contrast to our findings for adults, the use of regular care among youths increased slightly and the use of involuntary commitment and acute care decreased slightly after the reform. Overall, the cost-sharing reform was associated with estimated savings of €13.4 million (US$15.1 million). However, for adults with psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder, the additional costs of involuntary commitment and acute mental health care exceeded savings by €25.5 million (US$28.8 million).

Conclusions and Relevance

Higher cost sharing for seriously ill and low-income patients could discourage treatment of vulnerable populations and create substantial downstream costs.

Introduction

Patient cost sharing lowers health care spending because individuals tend to use fewer health services when they are required to pay a portion of the cost compared with full insurance. It has been argued in the health insurance literature that, if demand for certain health services is highly responsive to price changes, patients do not derive high value from those services. Because the demand for mental health services is highly responsive to price changes, some researchers have argued that there is an efficiency rationale for higher cost sharing for mental health care.

However, empirical work suggests that patients subject to cost sharing reduce their use of not only low-value but also high-value care. For certain illnesses, higher cost sharing may lead to undesirable consequences, potentially with downstream costs that more than offset the policy’s savings. For the patient, these broadly defined costs could include worse health from forgone treatment and the disutility of using downstream services relative to regular services. For society, these costs could include the greater expense of providing downstream services to patients in worse health. The literature raises several questions. Does the negative association between higher cost sharing and the use of mental health care vary based on observable patient characteristics? Is the reduced use of mental health care associated with an increase in downstream costs to the patient or society? If so, should cost sharing for certain patients be lower than for others?

We investigated these questions using a quasi-experimental study design in the Netherlands, where mandatory cost sharing for specialist mental health (including substance use) services was increased and a unique data set of treatment records for 87% of all specialist mental health patients from 2010 to 2012 was available. Our study assessed whether, after the reform, fewer adult patients received outpatient or inpatient treatment by income and major diagnosis category, including the seriously ill, who may benefit greatly from treatment. Because youths did not face the cost-sharing reform, they formed a natural unaffected control group to examine the influence of the cost-sharing reform on adult use of mental health services. Next, we investigated whether the reform was associated with greater involuntary commitment or acute mental health care use among adults and whether the resulting costs were outweighed by the savings from reduced regular care for each of the major diagnosis categories.

Methods

Setting

The Netherlands has a long history of universal health insurance with comprehensive coverage, low out-of-pocket expenditures, and premium subsidies for low-income individuals. Before 2012, the single health care–wide annual deductible, which applied to total costs summed across all types of specialist health care, had not been more than €170 (US$192). However, to combat increasing mental health care costs, the Dutch national government increased the out-of-pocket price for outpatient and inpatient specialist mental health care effective January 1, 2012. For outpatient care, adult patients were required to pay €100 (US$113) out of pocket to open a treatment record and an additional €100 (US$113) if they received a total of more than 100 minutes of care during that treatment record. For inpatient care, adult patients were required to pay a monthly co-pay of €150 (US$169). We therefore examined whether a higher out-of-pocket price for mental health care led to savings and negative downstream consequences. The data were deidentified before we obtained them, and the project was determined not human subjects research by Harvard's institutional review board. For these reasons, ethics approval was not required for this study.

A mental health treatment record worked as follows. The physician opened a treatment record when the patient started treatment, and a single treatment record covered all of the patient’s care for up to 365 days after the date that the record was opened. However, all treatment records automatically closed after 365 days; to continue treatment, a patient then had to open a new treatment record. Consequently, patients were affected by the postreform out-of-pocket prices if and only if their treatment record was opened in 2012.

The reform applied to all adults irrespective of their income but did not apply to youths (those 17 years or younger on the date when a treatment record was opened), did not affect the out-of-pocket price for medication or primary care, and did not apply to involuntary commitment or acute mental health care. Involuntary commitment occurred when a civil court of justice committed unwilling patients who presented a threat to themselves or others in accordance with the Law on Special Admissions in Psychiatric Hospitals. Acute mental health care, which was on a voluntary basis and could last no more than 28 days, was care offered only to individuals who required immediate treatment because they posed a threat to themselves or caused a public nuisance. Because the commitment procedure was involuntary and acute care could only last a short duration, involuntary commitment and acute care were unlikely to be substitutes for individuals who wanted to circumvent the postreform increase in the out-of-pocket price of regular care. See eMethods in the Supplement for additional institutional details.

Measure of Use and Data Source

The cost-sharing reform primarily affected an individual’s decision to open a treatment record as opposed to how much treatment to seek during a treatment record. Therefore, we measured mental health care use by the number of treatment records that were opened each day. Our data consisted of all individual-level, administrative mental health treatment records from all 110 member organizations of the Dutch association for mental health service providers (GGZ-NL) from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2012. Data analysis was performed from January 18, 2016, to May 9, 2017. Members of GGZ-NL treated 87% of all specialist mental health records in the Netherlands during the observation period. The remaining 13% of records had a relatively low degree of complexity and were treated by small organizations. For each treatment record, we observed the following: patient sex and year of birth, the start and end date of the record, the type of treatment, whether the patient received any acute mental health care during the record, one DSM-IV–based primary diagnosis code, the number of inpatient and outpatient treatment minutes, and the 4-digit postal code of the patient’s residence.

Study Population

We separated adults, those who turned 19 years or older in the year that they opened a treatment record and were thus affected by the reform, from youths, those who turned 15 through 17 years old and thus formed a control group that was unaffected by the reform. We observed year of birth rather than the exact date of birth; thus, we measured a patient’s age by subtracting the patient’s birth year from the year when the patient’s treatment record was opened. We could not determine whether individuals aged 18 years according to our measure were in fact 18 years of age (ie, affected by the reform if they started treatment in 2012) or 17 years of age (ie, youths unaffected by the reform) on the date when their treatment record was opened. For this reason, we excluded individuals aged 18 years from the analysis (eMethods in the Supplement). We also excluded those whom we measured as 14 years or younger to make our youth sample more comparable to the adult sample. For adults and youths, we created 3 mutually exclusive samples: a regular treatment sample, a sample with the involuntary commitment records, and a sample with the acute treatment records (eMethods in the Supplement).

From the recorded primary diagnosis, we classified each treatment record into 1 of 9 major diagnosis categories (eMethods and eTable 1 in the Supplement). This classification allowed us to compare our results for disorders that are considered to be on average more severe, such as psychotic disorder, personality disorder, or bipolar disorder, with those considered to be on average less severe, such as anxiety disorder or depressive disorder. To assign each patient to an income decile, we linked the postal code of a patient’s residence to the mean household income in 2012 for that postal code and the number of inhabitants in 2011 for that postal code (eMethods in the Supplement). To calculate costs for each record, we used the national tariff schedule for mental health insurance claims and an estimate for the additional procedural costs per record for involuntary commitment (eMethods in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

We used ordinary least squares regression models to estimate the association of the cost-sharing reform with mental health care use, involuntary commitment, and acute care. For each sample, our units of observation were the calendar days from January 1, 2010, through December 31, 2012. The dependent variable was the number of treatment records opened that day as a fraction of the mean number of treatment records opened per day in 2011. The independent variable of interest was an indicator for openings in 2012, and its coefficient measured the percentage change in daily openings between 2011 and 2012. This model controlled for openings in 2010, day of the week, and day of the year (eMethods in the Supplement). To investigate whether factors other than the reform were responsible for changes in use, we estimated a difference-in-differences model on the pooled sample of regular treatment records opened for adults and youths. This model contained interactions between all covariates from the baseline model and an indicator variable for being in the adult rather than the youth sample (eMethods in the Supplement).

For our figures, we obtained residuals from regressions that controlled for day of the week, day of the year, and holidays to separate structural changes from seasonal patterns. After adding the mean daily openings in 2011 to these residuals, we plotted these mean-shifted residuals to show detrended daily openings across the 3 years (eMethods in the Supplement). We calculated P values using a 2-sided t test. Because we tested multiple hypotheses, P < .002 was considered to be statistically significant at the 5% level. Analyses were performed using R software, version 3.3.1 (R Foundation).

Results

Characteristics of Treatment Records

This study included 1 448 541 treatment records of adults and youths opened from 2010 to 2012 (mean [SD] age, 41.4 [16.7] years; 712 999 men and 735 542 women). Table 1 provides the annual number of treatment records opened for the adult sample in regular care and a comparison of those records by observed characteristics (additional discussion of these characteristics is available in eResults in the Supplement). The raw growth rate of 3.9% from 2010 to 2011 was consistent with the mean annual growth rate of 5.6% in treatment between 2004 and 2010. By contrast, the raw decrease of 14.8% from 2011 to 2012 departed significantly from the prior annual trends (eFigure in the Supplement).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Regular Treatment Sample and Sizes for the Involuntary Commitment and Acute Care Samplesa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Treatment Records | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Total No. of regular treatment records | 435 290 | 452 165 | 393 667 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 210 507 (48.4) | 216 193 (47.8) | 191 729 (48.7) |

| Female | 224 783 (51.6) | 235 972 (52.2) | 201 938 (51.3) |

| Age group, y | |||

| 19-24 | 52 397 (12.0) | 53 944 (11.9) | 47 587 (12.1) |

| 25-34 | 92 382 (21.2) | 96 073 (21.2) | 83 401 (21.2) |

| 35-44 | 101 517 (23.3) | 103 419 (22.9) | 88 908 (22.6) |

| 45-54 | 93 454 (21.5) | 97 790 (21.6) | 84 663 (21.5) |

| 55-64 | 52 690 (12.1) | 55 266 (12.2) | 48 731 (12.4) |

| ≥65 | 42 850 (9.8) | 45 673 (10.1) | 40 377 (10.3) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Depressive disorder | 83 770 (19.2) | 89 853 (19.9) | 77 729 (19.7) |

| Substance-related disorder | 61 737 (14.2) | 58 857 (13.0) | 52 625 (13.4) |

| Anxiety disorder | 56 598 (13.0) | 60 151 (13.3) | 52 484 (13.3) |

| Psychotic disorder | 51 218 (11.8) | 54 122 (12.0) | 49 139 (12.5) |

| Personality disorder | 51 103 (11.7) | 55 934 (12.4) | 52 025 (13.2) |

| Missing | 45 841 (10.5) | 39 460 (8.7) | 26 110 (6.6) |

| Disorder first diagnosed in childhood | 32 646 (7.5) | 38 638 (8.5) | 34 582 (8.8) |

| Miscellaneous disorder | 31 062 (7.1) | 32 019 (7.1) | 27 093 (6.9) |

| Bipolar disorder | 21 315 (4.9) | 23 131 (5.1) | 21 880 (5.6) |

| Total time of treatment record, min | |||

| ≤500 | 163 649 (37.6) | 157 223 (34.8) | 113 384 (28.8) |

| 501-1500 | 137 363 (31.6) | 146 549 (32.4) | 131 282 (33.3) |

| 1501-2500 | 56 067 (12.9) | 63 255 (14.0) | 61 905 (15.7) |

| >2500 | 78 211 (18.0) | 85 138 (18.8) | 87 096 (22.1) |

| Other treatment records | |||

| Involuntary commitment | 921 | 1092 | 2156 |

| Acute treatment | 20 041 | 19 922 | 24 988 |

All samples contain only adults.

In addition, Table 1 provides the total annual number of treatment records opened for involuntary civil commitment and for acute care in the adult sample. Of the patients who were committed involuntarily, 63.7% were diagnosed with psychotic disorder and 12.6% with bipolar disorder. The median duration of an acute treatment record was 5 days (interquartile range, 2-17 days), and 64.2% of patients who received acute care had treatment records with a missing primary diagnosis (providers were not required to report a diagnosis on treatment records for acute care).

In contrast to our findings for adults, the use of regular care among youths increased slightly and the use of involuntary commitment and acute care decreased slightly after the reform (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Use and Downstream Effects

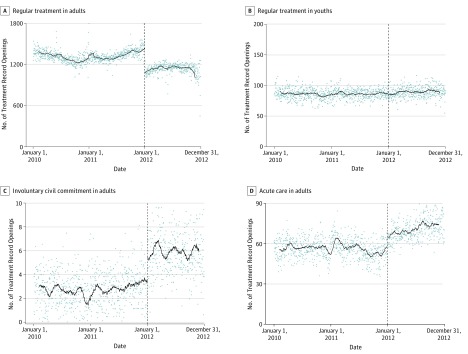

Conditional on covariates, the number of daily openings of regular treatment records among adults decreased persistently by 13.4% (95% CI, −16.0% to −10.8%; P < .001) when the cost-sharing reform was introduced on January 1, 2012 (Figure 1A, Table 2, and eTable 3 in the Supplement). In contrast, the number of daily openings of regular treatment records in the control group of unaffected youths increased slightly (Figure 1B and eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Our difference-in-differences model, which included adults and youths, yielded an estimate of −15.4% (95% CI, −18.5% to −12.3%; P < .001). This finding of reduced use remained significant when we accounted for the possibility that individuals may have anticipated the reform (eResults in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Daily Openings of Treatment Records by Sample, 2010-2012.

Daily openings of records represented by the mean-shifted residuals of daily openings of records on day-of-the-week, day-of-the-year, and holiday indicator variables. Fitted line is constructed as the moving mean of the previous 35 days for 2010 through 2011 and as the moving mean of the subsequent 35 days for 2012.

Table 2. Mental Health Care Use, Downstream Effects, and Heterogeneity Among Adultsa.

| Variable | Daily Openings in 2011, Mean (SD) | Change Between 2011 and 2012 (95% CI), %b | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of care | |||

| Regular | 1238.8 (588.3) | −13.4 (−16.0 to −10.8) | <.001 |

| Commitment | 3.0 (2.5) | 96.8 (87.7 to 105.9) | <.001 |

| Acute | 54.6 (15.0) | 25.1 (20.8 to 29.4) | <.001 |

| Regular treatment by income decile | |||

| 1st | 216.8 (94.0) | −16.3 (−19.0 to −13.5) | <.001 |

| 2nd | 183.2 (87.3) | −14.7 (−17.5 to −11.9) | <.001 |

| 3rd | 149.7 (70.7) | −13.7 (−16.3 to −11.1) | <.001 |

| 4th | 123.7 (62.3) | −12.6 (−15.1 to −10.0) | <.001 |

| 5th | 112.3 (57.8) | −13.8 (−16.5 to −11.1) | <.001 |

| 6th | 98.0 (52.8) | −11.7 (−14.5 to −8.9) | <.001 |

| 7th | 93.6 (46.8) | −12.1 (−14.4 to −9.9) | <.001 |

| 8th | 85.8 (48.6) | −11.4 (−14.6 to −8.2) | <.001 |

| 9th | 83.8 (44.5) | −10.2 (−13.2 to −7.2) | <.001 |

| 10th | 80.2 (41.7) | −11.3 (−14.6 to −8.1) | <.001 |

| Regular treatment by diagnosis | |||

| Depressive disorder | 246.2 (116.4) | −13.8 (−17.1 to −10.4) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 164.8 (75.4) | −13.1 (−16.2 to −10.0) | <.001 |

| Substance-related disorder | 161.3 (78.4) | −10.8 (−13.2 to −8.4) | <.001 |

| Personality disorder | 153.2 (74.5) | −7.4 (−10.2 to −4.6) | <.001 |

| Psychotic disorder | 148.3 (29.8) | −10.6 (−14.5 to −6.7) | <.001 |

| Missing | 108.1 (69.6) | −33.9 (−36.7 to −31.1) | <.001 |

| Disorder first diagnosed in childhood | 105.9 (47.6) | −10.8 (−13.3 to −8.2) | <.001 |

| Miscellaneous disorder | 87.7 (41.6) | −15.5 (−18.2 to −12.9) | <.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 63.4 (59.5) | −6.5 (−10.3 to −2.7) | <.001 |

Ordinary least squares regression of daily openings of treatment records divided by mean daily openings in 2011 on year, day-of-the-week, and day-of-the-year indicator variables. All samples contain only adults.

Estimated coefficient on the indicator for the year 2012. Coefficients on the indicators for 2010, day of the year, and day of the week not shown.

The number of daily records opened for adults increased by 96.8% (95% CI, 87.7%-105.9%; P < .001) for involuntary commitment and by 25.1% (95% CI, 20.8%-29.4%; P < .001) for acute care (Figure 1C and D and Table 2). The difference-in-differences estimates were similar: 96.7% (95% CI, 54.5%-138.9%; P < .001) for involuntary commitment and 29.6% (95% CI, 20.4%-38.9%; P < .001) for acute care.

Heterogeneity by Neighborhood Income and Major Diagnosis

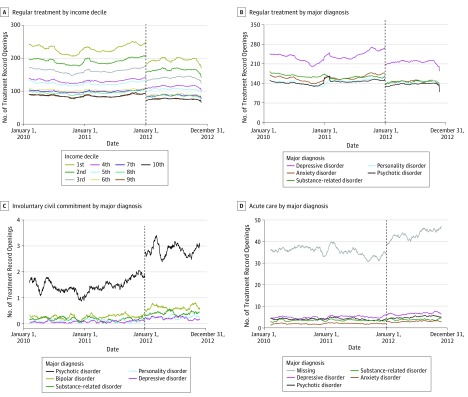

Figure 2A shows the overlaid residual plots for each of the 10 income deciles. Before the reform, treatment rates in the poorest decile had been 2.7 times higher than those in the richest decile. The reduction in the demand for treatment was significantly greater in poorer neighborhoods than in richer neighborhoods (Table 2 and eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Heterogeneity in Daily Openings of Treatment Records by Sample in Adults, 2010-2012.

Daily openings of records represented by the mean-shifted residuals of daily openings of records on day-of-the-week, day-of-the-year, and holiday indicator variables. Fitted line is constructed as the moving mean of the previous 35 days for 2010 through 2011 and as the moving mean of the subsequent 35 days for 2012. A, Fitted lines for each of the 10 income decimals. B-D, Fitted lines for the 5 largest major diagnosis categories for that sample.

Figure 2B shows the overlaid residual plots for the 5 major diagnoses with the greatest number of treatment records. Overall, the demand response was statistically significant for all major diagnosis categories (Table 2 and eTable 7 in the Supplement). The number of records opened each day for patients with psychotic disorder decreased by 10.6% (95% CI, −14.5% to −6.7%; P < .001), which was not much smaller than the estimated effect for patients with depressive disorder (−13.8%; 95% CI, −17.1% to −10.4%; P < .001) or anxiety disorder (−13.1%; 95% CI, −16.2% to −10.0%; P < .001).

Figure 2C shows that the increase in involuntary commitment after the reform was driven primarily by patients diagnosed with psychotic disorder and, to a lesser extent, by patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Figure 2D shows that the increase in acute care after the reform was driven by patients whose diagnoses were recorded as missing.

Costs vs Savings

Table 3 gives the estimated changes in mental health care spending after the reform by diagnosis. For adults, the annual number of regular treatment records decreased by 58 498, which generated total savings of €70.4 million (US$79.4 million). Meanwhile, involuntary commitment increased by 1064 and acute care increased by 5066, which generated total costs of €57.0 million (US$64.3 million). Consequently, the reform saved an estimated €13.4 million (US$15.1 million) more than it cost. Net savings were largest for depressive disorder at €15.3 million (US$17.3 million) and anxiety disorder at €9.8 million (US$11.1 million). However, net savings were negative for psychotic disorder at −€19.5 million (−US$22.0 million) and bipolar disorder at −€6.0 million (−US$6.8 million).

Table 3. Change in Net Treatment Costs for Specialist Mental Health Care After Cost-Sharing Reform.

| Diagnosis Group | Change in Regular Care Costs, € (US$) | Change in Acute and Commitment Costs, € (US$) | Change in Total Costs, € (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychotic disorder | −12 123 339 (−13 669 705) | 31 640 099 (35 675 883) | 19 516 760 (22 006 178) |

| Bipolar disorder | −1 424 480 (−1 606 176) | 7 414 818 (8 360 599) | 5 990 338 (6 754 423) |

| Personality disorder | −3 491 561 (−3 936 919) | 3 283 414 (3 702 223) | −208 147 (−234 697) |

| Missing | −2 135 140 (−2 407 484) | 1 214 963 (1 369 935) | −920 177 (−1 037 549) |

| Disorder first diagnosed in childhood | −3 877 689 (−4 372 299) | 2 161 148 (2 436 809) | −1 716 541 (−1 935 491) |

| Substance-related disorder | −10 366 451 (−11 688 721) | 4 943 812 (5 574 409) | −5 422 639 (−6 114 311) |

| Miscellaneous disorder | −6 708 884 (−7 564 621) | 1 221 542 (1 377 353) | −5 487 342 (−6 187 268) |

| Anxiety disorder | −10 959 769 (−12 357 719) | 1 113 139 (1 255 123) | −9 846 630 (−11 102 596) |

| Depressive disorder | −19 356 555 (−21 825 539) | 4 054 172 (4 571 293) | −15 302 383 (−17 254 246) |

| Total | −70 443 868 (−79 429 183) | 57 047 107 (64 323 627) | −13 396 761 (−15 105 556) |

Discussion

After 8 years of increases, the number of mental health treatment records opened by adults in the Netherlands decreased when cost sharing for mental health care increased in 2012. The size of this decrease was significant for severe and mild disorders and larger in low-income than in high-income neighborhoods. Simultaneously, among adults, involuntary commitment almost doubled and acute mental health care increased by 25% between 2011 and 2012. On aggregate, the reform was associated with estimated net savings in treatment costs of €13.4 million (US$15.1 million). However, for individuals with psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder, the additional costs for involuntary commitment and acute care exceeded savings by €25.5 million (US$28.8 million) because of fewer patients in regular care.

Our study is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate the influence of a patient cost-sharing reform for specialist mental health care only and to evaluate the consequences for patients across an entire country. Our empirical strategy is comparable to recent evaluations of cost-sharing reforms in Massachusetts and California and of the increase in the deductible of health insurance plans offered by a large US employer to its employees. Our research design has several advantages. First, our setting provided variation in mental health insurance coverage that was plausibly unrelated to other factors. Second, our estimates were based on observed behavior in response to a real-world policy change. Third, our data allowed us to obtain statistically precise estimates for heterogeneous effects based on patient characteristics of downstream costs as measured by types of treatment.

Our findings contribute to the health care literature and are relevant for policy makers. Because of the large increase in involuntary commitment and acute mental health care, it appears that at least some patients stopped regular treatment even though it was of high value. Optimal policy requires designing a system that incentivizes patients to use services for which the clinical and nonclinical benefits exceed monetary and nonmonetary costs and to forgo services for which the benefits do not justify the cost. Our results do not rule out that higher cost sharing incentivized certain individuals to reduce low-value care. However, the downstream costs that we observed for patients with psychotic disorder and bipolar disorder are an example of how cost sharing can increase rather than decrease total spending for certain populations.

Although the institutional context in the United States differs substantially from that in the Netherlands, where out-of-pocket maximums are lower on average, these results can inform the current US cost-sharing debate. The United States has seen an increase in the number of insured individuals after the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, as well as a reduction in the coverage gap between mental health care and other health services since the 1980s in large part because of parity legislation. However, average cost sharing for health services has increased among those with private health insurance. Furthermore, public policy seems to be headed toward less rather than more coverage. Our study suggests that reducing coverage for mental health care can lower mental health care costs overall but may have negative unintended consequences for the seriously ill.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, other factors could have influenced the use of mental health care at the time of the reform. However, we found no macroeconomic shocks, demographic shifts, or policy changes around January 1, 2012, that could explain the abrupt and persistent decrease in use in 2012. To control for any remaining factors, we relied on our difference-in-differences model, which used a sample of youths to construct counterfactual trends, and the results were consistent with the baseline estimates. Second, we could not link treatment records for individuals across time to identify the characteristics of those individuals who discontinued treatment after the reform. Third, we were unable to investigate whether, after the reform, patients substituted away from regular treatment and toward treatment by a primary care physician or by medication, although evidence from aggregate data on primary care use suggests that patients did not substitute toward primary care after the reform (eDiscussion in the Supplement). Fourth, we could not link treatment records to additional individual outcomes, and therefore were unable to assess the downstream costs of the policy on other medical costs or on other sectors of the economy in which the burden of untreated illness may be significant, such as the labor market and the criminal justice system.

Conclusions

Using data from the Netherlands, we examined the association of a national cost-sharing reform with mental health care use and downstream costs. A higher out-of-pocket price was associated with reduced use of mental health care, which generated aggregate savings but also increased costly use of involuntary commitment and acute care, particularly among individuals with psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder.

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eResults. Supplement Results

eFigure. Growth Rates Between 2004 and 2012

eTable 1. Diagnosis Codes

eTable 2. Characteristics of the Regular Treatment Sample and Sizes for the Involuntary Commitment and Acute Care Samples Among Youths

eTable 3. Absolute Mental Health Care Use, Downstream Effects, and Heterogeneity Among Adults

eTable 4. Mental Health Care Use, Downstream Effects, and Heterogeneity Among Youths

eTable 5. Absolute Mental Health Care Use, Downstream Effects, and Heterogeneity Among Youths

eTable 6. Differences of Coefficients by Income Decile

eTable 7. Differences of Coefficients by Diagnosis

eDiscussion. Supplemental Discussion

eReferences

References

- 1.Arrow KJ. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Econ Rev. 1963;53(2):941-973. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zweifel P, Manning WG. Moral hazard and consumer incentives in health care In: Culyer A, Newhouse J, eds. Handbook of Health Economics. Vol 1 Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Science BV; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutler DM, Zeckhauser RJ. The anatomy of health insurance In: Culyer A, Newhouse J, eds. Handbook of Health Economics. Vol 1 Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Science BV; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeckhauser R. Medical insurance: a case study of the tradeoff between risk spreading and appropriate incentives. J Econ Theory. 1970;2(1):10-26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank RG, McGuire TG. Economics and mental health In: Culyer A, Newhouse J, eds. Handbook of Health Economics. Vol 1 Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Science BV; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brot-Goldberg ZC, Chandra A, Handel BR, Kolstad JT. What Does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; October 2015. NBER working paper series working paper 21632.

- 7.Newhouse JP; The Insurance Experiment Group . Free for All? Lessons From the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baicker K, Goldman D. Patient cost-sharing and healthcare spending growth. J Econ Perspect. 2011;25(2):47-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. Patient cost-sharing and hospitalization offsets in the elderly. Am Econ Rev. 2010;100(1):193-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kreyenbuhl J, Nossel IR, Dixon LB. Disengagement from mental health treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strategies for facilitating connections to care: a review of the literature. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(4):696-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van de Ven WP, Schut FT. Universal mandatory health insurance in the Netherlands: a model for the United States? Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):771-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Bank Group World Development Indicators 2012. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Erf S, Boonzaaijer G, Heida JP. Acute geestelijke gezondheidszorg: knelpunten en verbetervoorstellen in de keten. The Hague: Strategies in Regulated Markets; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek Gemiddeld besteedbaar huishoudinkomen naar postcodegebied, 2012. http://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/maatwerk/2015/38/gemiddeld-besteedbaar-huishoudinkomen-naar-postcodegebied-2012. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- 15.Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek Bevolking en huishoudens; viercijferige postcode, 1 januari 2011. http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?VW=T&DM=SLNL&PA=81310NED&LA-NL. Accessed May 11, 2016.

- 16.Dutch Healthcare Authority Tariefbeschikking DBC GGZ 2012 TB/CU-5061-01. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Dutch Healthcare Authority; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trimbos Instituut Nulmeting monitor Wet Verplichte GGZ. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Trimbos Instituut; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM. Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J Econ Lit. 2009;47(1):5-86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Dijk S, Knispel A, Nuijen J. GGZ in Tabellen 2009. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Trimbos-instituut; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutch Healthcare Authority Marktscan en beleidsbrief Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg. Utrecht, the Netherlands: GGZ; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. Patient cost sharing in low income populations. Am Econ Rev. 2010;100(5):303-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. The impact of patient cost-sharing on low-income populations: evidence from Massachusetts. J Health Econ. 2014;33:57-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mark TL, Yee T, Levit KR, Camacho-Cook J, Cutler E, Carroll CD. Insurance financing increased for mental health conditions but not for substance use disorders, 1986–2014. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(6):958-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank RG. Realizing the promise of parity legislation for mental health. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(2):117-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, Damico A, Whitmore H, Foster G. Health benefits in 2016: family premiums rose modestly, and offer rates remained stable. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(10):1908-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wharam JF, Ross-Degnan D, Rosenthal MB. The ACA and high-deductible insurance—strategies for sharpening a blunt instrument. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1481-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goetzel RZ, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S. The health and productivity cost burden of the “top 10” physical and mental health conditions affecting six large U.S. employers in 1999. J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(1):5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eResults. Supplement Results

eFigure. Growth Rates Between 2004 and 2012

eTable 1. Diagnosis Codes

eTable 2. Characteristics of the Regular Treatment Sample and Sizes for the Involuntary Commitment and Acute Care Samples Among Youths

eTable 3. Absolute Mental Health Care Use, Downstream Effects, and Heterogeneity Among Adults

eTable 4. Mental Health Care Use, Downstream Effects, and Heterogeneity Among Youths

eTable 5. Absolute Mental Health Care Use, Downstream Effects, and Heterogeneity Among Youths

eTable 6. Differences of Coefficients by Income Decile

eTable 7. Differences of Coefficients by Diagnosis

eDiscussion. Supplemental Discussion

eReferences