This study examines simultaneous new benzodiazepine and antidepressant use among adults with depression, antidepressant treatment length by simultaneous new use status, subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in those taking both an antidepressant and a benzodiazepine, and determinants of simultaneous new use and long-term benzodiazepine use.

Key Points

Questions

When adults with depression begin antidepressant therapy, how often do they simultaneously begin benzodiazepine therapy, does antidepressant treatment length differ in patients with simultaneous new use of an antidepressant and benzodiazepine, and how often does beginning use of the medications together result in long-term benzodiazepine use?

Finding

In this cohort study of 765 130 adults who started taking an antidepressant, 81 020 also started taking a benzodiazepine the same day, with the proportion of patients with simultaneous new antidepressant and benzodiazepine use increasing from 6.1% in 2001 to 12.5% in 2012 (then plateauing through 2014). No clinically meaningful difference in antidepressant treatment continuation by simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use was found, and 12.3% of patients who began treatment with both these agents had long-term (6-month) benzodiazepine use.

Meaning

The decision to prescribe a benzodiazepine when a patient begins antidepressant therapy requires careful consideration of potential benefits and harms.

Abstract

Importance

Benzodiazepines have been prescribed for short periods to patients with depression who are beginning antidepressant therapy to improve depressive symptoms more quickly, mitigate concomitant anxiety, and improve antidepressant treatment continuation. However, benzodiazepine therapy is associated with risks, including dependency, which may take only a few weeks to develop.

Objectives

To examine trends in simultaneous benzodiazepine and antidepressant new use among adults with depression initiating an antidepressant, assess antidepressant treatment length by simultaneous new use status, estimate subsequent long-term benzodiazepine use in those with simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use, and identify determinants of simultaneous new use and long-term benzodiazepine use.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study using a US commercial claims database included commercially insured adults (aged 18-64 years) from January 1, 2001, through December 31, 2014, with a recent depression diagnosis who began antidepressant therapy but had not used antidepressants or benzodiazepines in the prior year.

Exposures

Simultaneous new use, defined as a new benzodiazepine prescription dispensed on the same day as a new antidepressant prescription.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The proportion of antidepressant initiators with simultaneous new use and continuing antidepressant treatment for 6 months and the proportion of simultaneous new users receiving long-term (6-months) benzodiazepine therapy.

Results

Of the 765 130 adults (median age, 39 years; interquartile range, 29-49 years; 507 451 women [66.3%]) who initiated antidepressant treatment, 81 020 (10.6%) also initiated benzodiazepine treatment. The mean annual increase in the proportion simultaneously starting use of both agents from 2001 to 2014 was 0.49% (95% CI, 0.47%-0.51%), increasing from 6.1% (95% CI, 5.5%-6.6%) in 2001 to 12.5% (95% CI, 12.3%-12.7%) in 2012 and stabilizing through 2014 (11.3%; 95% CI, 11.1%-11.5%). Similar findings were apparent by age group and physician type. Antidepressant treatment length was similar in simultaneous new users and non–simultaneous new users. Among simultaneous new users, 12.3% (95% CI, 12.0%-12.5%) exhibited long-term benzodiazepine use (64.0% discontinued taking benzodiazepines after the initial fill). Determinants of long-term benzodiazepine use after simultaneous new use were longer initial benzodiazepine days’ supply, first prescription for a long-acting benzodiazepine, and recent prescription opioid fills.

Conclusions and Relevance

One-tenth of antidepressant initiators with depression simultaneously initiated benzodiazepine therapy. No meaningful difference in antidepressant treatment at 6 months was observed by simultaneous new use status. Because of the risks associated with benzodiazepines, simultaneous new use at antidepressant initiation and the benzodiazepine regimen itself require careful consideration.

Introduction

When patients with depression begin antidepressant therapy, sometimes a benzodiazepine is added to the therapy to mitigate the anxiety and insomnia that occur with depression, reduce depression severity more quickly, and improve antidepressant persistence. Because benzodiazepine dependency may develop quickly, practice guidelines recommend only short-term benzodiazepine use. For example, the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence depression guideline cautions against using a benzodiazepine for more than 2 weeks when prescribed to patients also taking antidepressants, noting further that it remains unclear whether starting benzodiazepine therapy at antidepressant therapy initiation produces desirable effects in efficacy or tolerability.

Despite cautions and concerns, benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed during antidepressant treatment; 10% to 57% of antidepressant users receive benzodiazepines or other anxiolytics at some time during antidepressant treatment. Less is known about the specific practice of simultaneously beginning benzodiazepine therapy with antidepressant therapy. The largest US study used Veterans Health Administration data and found that 7.6% of adults with depression who initiated antidepressant treatment in 2007 also initiated benzodiazepine treatment on the same day; 14.1% continued benzodiazepine treatment for 1 year. Patients who simultaneously started use of these drugs were more likely to have anxiety and to visit a psychiatrist.

Comparable statistics for privately insured adults in the United States, who comprise 64% of all US adults aged 18 to 64 years in 2012, have not been published, to our knowledge. To address current research gaps in US commercially insured adults, we describe (1) how frequently antidepressant initiators simultaneously start benzodiazepine therapy, (2) changes in simultaneous new use over time, and (3) the proportion of simultaneous new users who become long-term benzodiazepine users. In addition, we assessed whether antidepressant treatment length varies between simultaneous new users and non–simultaneous new users and identify determinants of simultaneous new use and long-term benzodiazepine use.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We used Truven’s MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. The database includes claims for inpatient and outpatient diagnoses, procedure codes, and records for reimbursed, dispensed prescriptions for privately insured individuals. The study population consisted of adults aged 18 to 64 years with a recent depression diagnosis who initiated antidepressant treatment from January 1, 2001, through December 31, 2014. Included adults had no record of a benzodiazepine or antidepressant prescription in the year before antidepressant treatment initiation. All antidepressant types were included (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, bupropion, tricyclic antidepressants, and others). Benzodiazepines included alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clorazepate dipotassium, diazepam, oxazepam, lorazepam, clobazam, flurazepam, estazolam, triazolam, temazepam, midazolam, quazepam, and clonazepam. Similar to the meta-analysis on randomized clinical trials of benzodiazepine and antidepressant therapy compared with antidepressant therapy alone, we did not include drugs with similar properties, such as z drugs (eg, zolpidem). Depression was defined as a recorded inpatient or outpatient diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes 296.20-296.25, 296.30-296.35, 300.4x, 311.x, 309.28, 309.0-309.1) in the 30 days before or on the date of antidepressant treatment initiation to capture patients initiating use of the antidepressant for depression. The index depression diagnosis was defined as the diagnosis on the day of or before antidepressant treatment initiation. Patients were required to have continuous insurance enrollment in the year before antidepressant treatment initiation. Patients with a recorded diagnosis of substance abuse, personality disorder, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia in the year before antidepressant treatment initiation were excluded. This study was exempted from review by the University of North Carolina’s Institutional Review Board; therefore, no informed consent was required.

Simultaneous New Use

Simultaneous new use was defined as a record of a dispensed benzodiazepine prescription on the date of antidepressant treatment initiation. All patients were previously naive to treatment with antidepressants and benzodiazepines. Sensitivity analyses defined simultaneous new use as a benzodiazepine dispensed up to 30 days after antidepressant treatment initiation.

Antidepressant Treatment Length

Antidepressant treatment length was defined as the number of days from antidepressant treatment initiation to discontinuation. After the date of antidepressant treatment initiation, the days’ supply was added to a 30-day grace period to allow for gaps in treatment between fills. If no subsequent prescription was dispensed in the previous prescription’s days’ supply plus the grace period, the patient was considered to have discontinued treatment at the end of that period. We highlight antidepressant treatment continuation at 6 months because guidelines recommend 6 or more months of treatment in adults with depression but also report results up to 2 years.

Long-term Use of Benzodiazepine

Applying a commonly used definition, we defined long-term benzodiazepine use as 6 months (180 days) of continuous benzodiazepine use after simultaneous new use with antidepressant treatment. We estimated benzodiazepine treatment length using a 30-day grace period; sensitivity analyses varied the grace period from a more restrictive (10 days) to a less restrictive definition (60 days). We also counted the number of benzodiazepine prescription fills before discontinuation of use.

Patient and Prescribing Characteristics

Patient and prescribing characteristics were based on the presence of diagnostic and procedure codes and dispensed prescriptions in the year before antidepressant initiation. These characteristics included age, sex, psychiatric comorbidities (specific consideration to anxiety disorders), treated self-harm, nonpsychiatric comorbidities (included individually and not part of an index), health care use (often used as a proxy for health-seeking behavior and overall health), and region. We also included year of antidepressant treatment initiation, initial antidepressant class, and a marker for recorded psychotherapy sessions (Current Procedural Terminology psychotherapy codes) in the 30 days before antidepressant treatment initiation. Although we lack direct measures of baseline depression severity, for the index depression diagnosis we included the specific depression diagnosis, whether the index episode was diagnosed in the hospital or as an outpatient, and the physician specialty associated with the diagnosis. Because benzodiazepines have been associated with fractures and the potential harms of concurrent benzodiazepine and opioid use, we included indicators for recent opioid prescriptions, prior injuries, and fall or fracture risk factors.

We characterized the initial benzodiazepine prescription in terms of days’ supply and quantity of pills dispensed, pills per day prescribed (quantity divided by days’ supply), whether the agent was long-acting (clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, flurazepam, or quazepam), and whether the dose per day (prescription strength × pills per day) was above, below, or at the modal dose. Modal dose per day was determined by the mode dose for each benzodiazepine agent. For patients with more than 1 benzodiazepine agent (0.9%) dispensed at treatment initiation or more than 1 prescription for the same agent (0.5%), we summed initial days’ supply, quantity, and pills per day values.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the proportion of simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine users among all antidepressant initiators by year, stratified by age group and physician type. We estimated the mean annual increase and 95% CIs in the proportion of simultaneous new users, assuming a linear trend. Figures depicting trends were internally standardized by region, age, and sex. We used weighted survival curves to estimate antidepressant continuation by simultaneous new use status with censoring at insurance disenrollment and the end of the study period. For weighted analyses, we used stabilized-inverse probability of treatment weights with patient characteristics likely to be associated with simultaneous new use and antidepressant treatment continuation entered into the propensity score model. Among simultaneous new users, we described characteristics of the initial benzodiazepine prescription regimen overall and stratified by the physician specialty of the index depression diagnosis and estimated the survival function of continued benzodiazepine use, censoring at insurance disenrollment and the end of the study period.

We used Poisson regression with robust variance estimation to estimate crude risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs and multivariable RRs to identify factors independently associated with (1) simultaneous new use and (2) long-term benzodiazepine use. Because of the exploratory nature of the analysis, we included all the aforementioned patient and prescribing characteristics in the models. We then removed characteristics independently associated with less than 5% increased or decreased likelihood of (1) simultaneous new use or (2) long-term use from the full model. The C statistics for each full model are reported. Factors associated with long-term benzodiazepine use were evaluated in simultaneous new users with 6 months of follow-up.

Results

Of the 765 130 adults (median age, 39 years; interquartile range, 29-49 years; 507 451 women [66.3%]) who started antidepressant therapy, 81 020 (10.6%) simultaneously started benzodiazepine therapy. Of adults with a recent anxiety or sleep disorder diagnosis, 20.2% were simultaneous new users compared with 8.4% without comorbid anxiety or sleep disorder.

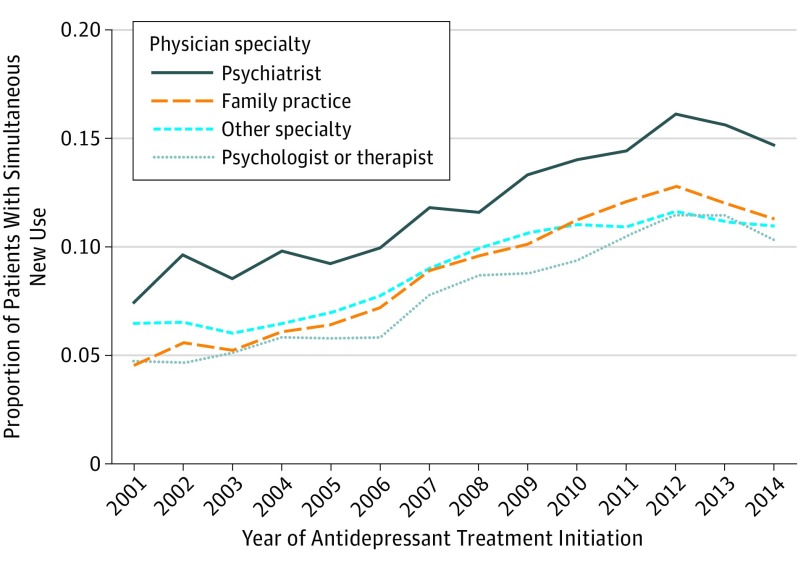

Trends in Simultaneous New Use

The proportion of simultaneous new users increased from 6.1% of antidepressant initiators in 2001 to a peak of 12.5% in 2012. The mean annual increase in the proportion of simultaneous new users was 0.49% (95% CI, 0.47%-0.51%). This trend held although with different baseline frequencies when stratified by physician type and age. A higher proportion of patients diagnosed with depression by psychiatrists were simultaneous new users (2001, 8.7%; 2012, 16.1%) compared with other physician types (eg, family practice: 2001, 5.0%; 2012, 12.8%) (Figure 1). The highest mean annual change occurred among patients aged 25 to 34 years (0.70%; 95% CI, 0.65%-0.75%) and the lowest among those 18 to 24 (0.40%) and 50 to 64 (0.36%) years of age (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Proportion of Patients With Simultaneous New Use of an Antidepressant and a Benzodiazepine by Specialty of Physician Providing the Index Diagnosis of Depression.

Internally standardized (reference year, 2012) by age group, sex, and region; patients with unknown region and physician specialty were excluded (remaining n = 687 170).

Determinants of Benzodiazepine and Antidepressant Simultaneous New Use

Having a recent anxiety diagnosis was the strongest determinant of simultaneous new use of a benzodiazepine (Table 1 and eTable 1 in the Supplement). Specifically, 24.1% of patients with a recent unspecified anxiety diagnosis (multivariable RR [RR], 2.58; 95% CI, 2.54-2.62) and 39.1% with a recent panic disorder diagnosis (RR, 2.67; 95% CI, 2.58-2.76) had simultaneous benzodiazepine and antidepressant new use. Simultaneous new use was more common among patients with recent insomnia or sleep disturbance diagnoses (RR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.28-1.34) and less common among those who received recent psychotherapy (RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.81-0.85) or had a history of self-harm (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.59-0.92).

Table 1. Characteristics of Simultaneous Antidepressant and Benzodiazepine New Users and Non–Simultaneous Antidepressant New Users With Depression and Factors Associated With Simultaneous New Usea.

| Variable | Non–Simultaneous New Usersb (n = 684 110) |

Simultaneous New Usersb (n = 81 020) |

Simultaneous New Use | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous New Users, % (95% CI) | Crude RR | Multivariable RRc (95% CI) | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 231 600 (33.9) | 26 079 (32.2) | 10.1 (10.0-10.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 452 510 (66.1) | 54 941 (67.8) | 10.8 (10.7-10.9) | 1.07 | 1.09 (1.08-1.11) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 39 (29-49) | 39 (30-49) | NA | NA | NA |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 18-24 | 120 403 (17.6) | 10 140 (12.5) | 7.8 (7.6-7.9) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 25-34 | 144 620 (21.1) | 19 358 (23.9) | 11.8 (11.6-12.0) | 1.52 | 1.59 (1.56-1.63) |

| 35-49 | 249 217 (36.4) | 32 715 (40.4) | 11.6 (11.5-11.7) | 1.49 | 1.68 (1.64-1.71) |

| 50-64 | 169 870 (24.8) | 18 807 (23.2) | 10.0 (9.8-10.1) | 1.28 | 1.55 (1.51-1.59) |

| Initial antidepressant class | |||||

| SSRI | 474 001 (69.3) | 64 460 (79.6) | 12.0 (11.9-12.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| SNRI | 65 935 (9.6) | 5554 (6.9) | 7.8 (7.6-8.0) | 0.65 | 0.69 (0.67-0.70) |

| Bupropion | 86 725 (12.7) | 5667 (7.0) | 6.1 (6.0-6.3) | 0.51 | 0.57 (0.56-0.59) |

| Other | 57 449 (8.4) | 5339 (6.6) | 8.5 (8.3-8.7) | 0.71 | 0.65 (0.63-0.67) |

| Depression diagnosis (index diagnosis)d | |||||

| Not otherwise specified | 339 912 (49.7) | 32 443 (40.0) | 8.7 (8.6-8.8) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Major depressive disorder | 178 503 (26.1) | 23 466 (29.0) | 11.6 (11.5-11.8) | 1.33 | 1.40 (1.38-1.43) |

| Other | 165 695 (24.2) | 25 111 (31.0) | 13.2 (13.0-13.3) | 1.51 | 1.75 (1.72-1.78) |

| Inpatient index depression diagnosis | 13 144 (1.9) | 2398 (3.0) | 15.4 (14.9-16.0) | 1.47 | 1.34 (1.29-1.40) |

| Nonrecent depression diagnosis | 161 261 (23.6) | 13 328 (16.5) | 7.6 (7.5-7.8) | 0.67 | 0.71 (0.69-0.72) |

| Specialty of physician who provided index depression diagnosis | |||||

| Family practice | 229 862 (33.6) | 27 350 (33.8) | 10.6 (10.5-10.8) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Psychiatry | 86 879 (12.7) | 13 398 (16.5) | 13.4 (13.2-13.6) | 1.26 | 1.32 (1.29-1.35) |

| Psychologist or therapist | 70 953 (10.4) | 6673 (8.2) | 8.6 (8.4-8.8) | 0.81 | 0.85 (0.83-0.88) |

| Other specialty | 234 533 (34.3) | 26 513 (32.7) | 10.2 (10.0-10.3) | 0.96 | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) |

| Unknown or multiple physicians | 61 883 (9.0) | 7086 (8.7) | 10.3 (10.0-10.5) | 0.97 | 0.93 (0.91-0.96) |

| Anxiety disorder diagnosis, recent | |||||

| Unspecified anxiety | 52 389 (7.7) | 16 651 (20.6) | 24.1 (23.8-24.4) | 2.61 | 2.58 (2.54-2.62) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 21 350 (3.1) | 5705 (7.0) | 21.1 (20.6-21.6) | 2.07 | 1.90 (1.85-1.95) |

| Panic disorder | 4471 (0.7) | 2870 (3.5) | 39.1 (38.0-40.2) | 3.79 | 2.67 (2.58-2.76) |

| PTSD | 4819 (0.7) | 783 (1.0) | 14.0 (13.1-14.9) | 1.32 | 1.14 (1.05-1.22) |

| OCD, phobic disorder, or other anxiety | 5910 (0.9) | 1465 (1.8) | 19.9 (19.0-20.8) | 1.89 | 1.47 (1.40-1.55) |

| Insomnia or sleep disturbance diagnosis, recent | 39 006 (5.7) | 6618 (8.2) | 14.5 (14.2-14.8) | 1.40 | 1.31 (1.28-1.34) |

| ADHD | 20 452 (3.0) | 1329 (1.6) | 6.1 (5.8-6.4) | 0.57 | 0.63 (0.59-0.66) |

| Acute reaction to stress | 9030 (1.3) | 1936 (2.4) | 17.7 (17.0-18.4) | 1.68 | 1.43 (1.37-1.49) |

| Treated self-harm | 861 (0.1) | 83 (0.1) | 8.8 (7.1-10.8) | 0.83 | 0.74 (0.59-0.92) |

| Psychotherapy, recent | |||||

| None recorded | 529 351 (77.4) | 64 845 (80.0) | 10.9 (10.8-11.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| ≥1 Session | 154 759 (22.6) | 16 175 (20.0) | 9.5 (9.3-9.6) | 0.87 | 0.83 (0.81-0.85) |

| Epilepsy or recurrent seizures | 3458 (0.5) | 321 (0.4) | 8.5 (7.6-9.4) | 0.80 | 0.80 (0.72-0.89) |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RR, risk ratio; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Characteristics were defined using inpatient and outpatient International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnostic codes; Current Procedural Terminology, fourth edition, procedure codes; and outpatient dispensed prescriptions. A full list of characteristics is given in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Recent refers to measures within the 30 days before antidepressant treatment initiation (nonrecent: 31-365 days before treatment initiation).

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Multivariable RRs are adjusted for all the variables in eTable 1 in the Supplement and include the following: additional psychiatric comorbidities (adjustment disorder, nonrecent anxiety diagnosis, or other episodic mood disorder), fall or fracture risk factures (fracture, bone mineral density scan, osteoporosis, cataracts or glaucoma, or visual loss or disturbance), poisoning, nonpsychiatric comorbidities (cardiac disorders, chronic kidney disease, osteoarthritis and allied disorders, Crohn disease or gastroenteritis, diabetes, fatigue, hearing problem, hypertension, hypothyroidism, overweight or obese, or urinary incontinence), health care use measures (outpatient visits, inpatient admission, or medication use), region, and year of treatment initiation. The full model resulted in a C statistic of 0.697.

For index depression diagnosis, other includes adults diagnosed with dysthymic disorder, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, or prolonged depressive reaction; not otherwise specified includes adults without a specific diagnosis.

In sensitivity analyses using the 30-day definition of simultaneous new use, 13.6% of antidepressant initiators were simultaneous new users. The trend from 2001 to 2014 remained, peaking at 15.7% in 2012. Strong determinants of simultaneous new use in primary analyses remained strong, with only slight alterations in their magnitude of association.

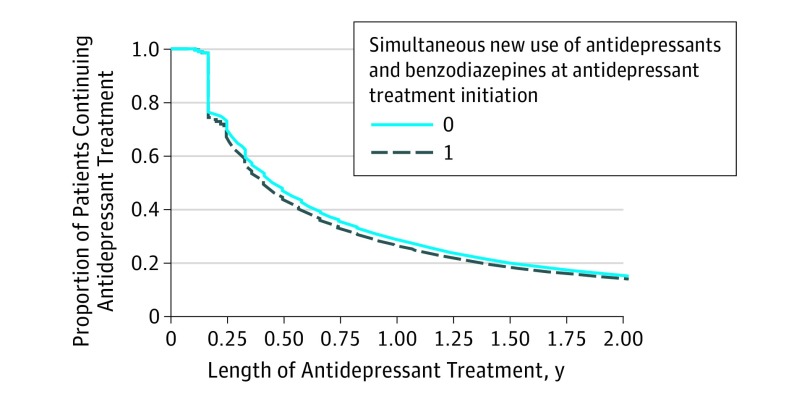

Antidepressant Treatment Length

A total of 67.3% of simultaneous new users and 70.3% of non–simultaneous new users continued antidepressant treatment at 3 months; 44.3% of simultaneous new users and 47.1% of non–simultaneous new users continued to take antidepressants at 6 months. After propensity score weighting, crude imbalances between simultaneous new users and non–simultaneous new users were mitigated, but results at 6 months were unchanged (non–simultaneous new users, 47.1%; simultaneous new users, 43.9%) (Figure 2). Continued antidepressant use at 6 months was similar in the subset of adults with major depressive disorder (n = 201 969; non–simultaneous new users, 48.1%; simultaneous new users, 45.6%).

Figure 2. Antidepressant Treatment Length in Simultaneous New Users and Non–Simultaneous New Users of an Antidepressant and a Benzodiazepine.

For adjusted analyses, we used stabilized-inverse probability of treatment weights. Variables entered into the propensity score model (collected in the year before antidepressant initiation) include sex, age, antidepressant type, specific depression diagnosis, inpatient depression diagnosis, physician type, treated self-harm event, psychotherapy use, psychiatric comorbidities with markers for anxiety disorders, and markers of health care use (outpatient visits and medication count). In the unweighted cohort, 24.1% of simultaneous new users and 22.5% of non–simultaneous new users had less than 6 months of insurance enrollment after antidepressant initiation.

Benzodiazepine Prescription Details

Most benzodiazepine users had an initial prescription for alprazolam (43.9%), lorazepam (26.3%), or clonazepam (21.8%). A total of 13.5% received a short benzodiazepine days’ supply (1-7 days) at the start of treatment, with variation by physician specialty (psychiatry, 6.7%; family practice, 15.1%). A total of 26.1% of simultaneous new users received more than 50 benzodiazepine pills at the start of treatment, an indication of prescribing more than 1 pill per day. We present full benzodiazepine prescription details overall and by physician in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Long-term Benzodiazepine Use

A total of 12.3% (95% CI, 12.0%-12.5%) of simultaneous new users received long-term benzodiazepine treatment, with 5.7% (95% CI, 5.5%-5.9%) continuing benzodiazepine therapy for 1 year. Of simultaneous new users, 6.2% under the shortened (10 days) and 22.0% under the lengthened (60 days) grace periods were defined as long-term users. The proportion of simultaneous new users becoming long-term users remained fairly stable from 2001 to 2014 (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Among simultaneous new users with 6 months or more of insurance enrollment after the start of treatment (61 482 [75.9%]), 64.0% did not refill their initial benzodiazepine prescription, and 14.8% had 4 or more refills before treatment discontinuation (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of Benzodiazepine Fills Among Simultaneous New Users of an Antidepressant and a Benzodiazepine by Grace Period Used to Define Benzodiazepine Treatment Discontinuationa.

| Benzodiazepine Fills Before Treatment Discontinuation | No. (%) of Patients (n = 61 482)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analysis: 30-d Grace Period | Sensitivity Analyses | ||

| 10-d Grace Period | 60-d Grace Period | ||

| 1 (no refill) | 39 369 (64.0) | 46 477 (75.6) | 35 189 (57.2) |

| 2 | 9237 (15.0) | 7057 (11.5) | 9696 (15.8) |

| 3 | 3796 (6.2) | 2656 (4.3) | 4300 (7.0) |

| ≥4 | 9080 (14.8) | 5292 (8.6) | 12 297 (20.0) |

Grace period indicates the number of days without medication between fills that is allowed before a patient was known to have discontinued benzodiazepine therapy.

Restricted to simultaneous new users with 6 months of follow-up (n = 61 482).

When simultaneously considering long-term benzodiazepine use and antidepressant treatment continuation in adults with 6-month follow-up, 34.9% continued antidepressant treatment and discontinued benzodiazepine treatment 6 months after the start of treatment, 8.3% continued both antidepressant and benzodiazepine treatment, 54.4% discontinued both antidepressant and benzodiazepine treatment, and 2.4% continued benzodiazepine treatment and discontinued antidepressant treatment.

The likelihood of becoming a long-term benzodiazepine user varied by patient and prescription characteristics (Table 3 and eTable 3 in the Supplement). Patients with an initial days’ supply of 8 to 15 days (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.30-1.64), 22 to 35 days (RR, 2.91; 95% CI, 2.54-3.33), and more than 35 days (RR, 4.90; 95% CI, 4.15-5.79; prevalence, 2%) were more likely to become long-term users than were patients with 1 to 7 days’ supply. Older adults (50-64 vs 18-24 years of age; RR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.17-1.38), patients initiating a long-acting benzodiazepine (RR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.22-1.34), and patients diagnosed with depression by a psychiatrist vs family practitioner (RR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.27-1.47) were more likely to become long-term users. Prior poisoning (RR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.01-1.64) and a recent opioid prescription (RR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.39-1.61) at baseline were also associated with an increased likelihood of becoming a long-term user.

Table 3. Long-term Benzodiazepine Use Among Simultaneous New Users by Baseline Patient Characteristic and Initial Prescription Detailsa.

| Variable | Non–Long-term Benzodiazepine Usersb (n = 54 900) |

Long-term Benzodiazepine Usersb (n = 6582) |

Long-term Benzodiazepine Use, RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Multivariablec | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 17 091 (31.1) | 2610 (39.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 37 809 (68.9) | 3972 (60.3) | 0.72 | 0.78 (0.74-0.81) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 39 (31-49) | 42 (32-51) | NA | NA |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 18-24 | 6806 (12.4) | 706 (10.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 25-34 | 12 740 (23.2) | 1270 (19.3) | 0.96 | 1.00 (0.92-1.09) |

| 35-49 | 22 642 (41.2) | 2753 (41.8) | 1.15 | 1.15 (1.07-1.25) |

| 50-64 | 12 712 (23.2) | 1853 (28.2) | 1.35 | 1.27 (1.17-1.38) |

| Depression diagnosis (index diagnosis)d | ||||

| Not otherwise specified | 22 134 (40.3) | 2203 (33.5) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Major depressive disorder | 15 411 (28.1) | 2744 (41.7) | 1.67 | 1.19 (1.12-1.26) |

| Other | 17 355 (31.6) | 1635 (24.8) | 0.95 | 0.95 (0.90-1.01) |

| Specialty of physician who provided index depression diagnosis | ||||

| Family practice | 18 655 (34.0) | 1675 (25.4) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Psychiatry | 8661 (15.8) | 1884 (28.6) | 2.17 | 1.37 (1.27-1.47) |

| Other specialty | 18 185 (33.1) | 1968 (29.9) | 1.19 | 1.08 (1.02-1.15) |

| Psychologist, therapist | 4826 (8.8) | 524 (8.0) | 1.19 | 1.03 (0.94-1.14) |

| Unknown or multiple physicians | 4573 (8.3) | 531 (8.1) | 1.26 | 1.08 (0.98-1.18) |

| Short- vs long-acting benzodiazepine | ||||

| Short or intermediate acting | 41 820 (76.2) | 4283 (65.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Long actinge | 13 080 (23.8) | 2299 (34.9) | 1.61 | 1.28 (1.22-1.34) |

| Benzodiazepine index days’ supply,e d | 15 (10-30) | 30 (15-30) | ||

| 1-7 | 7948 (14.5) | 373 (5.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 8-21 | 24 154 (44.0) | 1790 (27.2) | 1.54 | 1.46 (1.30-1.64) |

| 22-35 | 22 041 (40.1) | 4103 (62.3) | 3.50 | 2.91 (2.54-3.33) |

| >35 | 756 (1.4) | 316 (4.8) | 6.58 | 4.90 (4.15-5.79) |

| Initial benzodiazepine quantity dispensed,e pills | 30 (30-50) | 30 (30-60) | ||

| 1-24 | 13 171 (24.0) | 767 (11.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 25-50 | 28 306 (51.6) | 3252 (49.4) | 1.87 | 1.18 (1.08-1.29) |

| >50 | 13 422 (24.4) | 2563 (38.9) | 2.91 | 1.14 (1.01-1.27) |

| Anxiety disorder diagnosis, recent | ||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3443 (6.3) | 529 (8.0) | 1.27 | 1.16 (1.07-1.25) |

| Panic disorder | 1735 (3.2) | 249 (3.8) | 1.18 | 1.15 (1.02-1.29) |

| PTSD | 496 (0.9) | 75 (1.1) | 1.23 | 1.08 (0.83-1.39) |

| OCD, phobic disorder, or other anxiety | 893 (1.6) | 171 (2.6) | 1.51 | 1.27 (1.10-1.45) |

| Nonrecent insomnia or sleep disturbance diagnosis | 1939 (3.5) | 329 (5.0) | 1.37 | 1.23 (1.11-1.37) |

| Acute reaction to stress | 1307 (2.4) | 102 (1.5) | 0.67 | 0.76 (0.63-0.92) |

| Outpatient problem-oriented visits | ||||

| 0-1 | 10 592 (19.3) | 1548 (23.5) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 2-6 | 32 327 (58.9) | 3531 (53.6) | 0.77 | 0.86 (0.81-0.92) |

| >6 | 11 981 (21.8) | 1503 (22.8) | 0.87 | 0.83 (0.76-0.90) |

| Opioid prescription, recent | 3723 (6.8) | 773 (11.7) | 1.69 | 1.50 (1.39-1.61) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RR, risk ratio.

Characteristics were defined using inpatient and outpatient International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnostic codes; Current Procedural Terminology, fourth edition, procedure codes; and outpatient dispensed prescriptions. A full list of characteristics is given in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Multivariable RRs are adjusted for all the variables in eTable 3 in the Supplement and include, in addition to the variables in Table 3, the following: antidepressant class, inpatient depression diagnosis, benzodiazepine dose per day, psychiatric comorbidities (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, adjustment disorder, or other episodic mood disorder), treated self-harm, nonrecent anxiety diagnosis, recent insomnia or sleep disturbance diagnosis, fall or fracture risk factures (fracture, fall injury, cataracts or glaucoma, or visual loss or disturbance), poisoning, nonpsychiatric comorbidities (cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease, osteoarthritis and allied disorders, Crohn disease or gastroenteritis, hearing problem, overweight or obese, or urinary incontinence), health care use measures (inpatient admission, medication use), region, and year of treatment start. One person was excluded from multivariable analyses who started taking a benzodiazepine in solution form. The full model resulted in a C statistic of 0.700.

For index depression diagnosis, other includes adults diagnosed with dysthymic disorder, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, or prolonged depressive reaction; not otherwise specified includes adults without a specific diagnosis; and recent refers to measures within 30 days before antidepressant treatment initiation.

Days’ supply and quantity values of 0 or less were set to the median value (30), days’ supply values greater than 99 were truncated to 100, and quantity values greater than 200 were truncated to 200 (2% of all prescriptions). For patients with multiple agents (0.9%), if one agent was long acting, patients were classified as initiating treatment with a long-acting agent.

Discussion

A total of 10.6% of commercially insured adults who started taking an antidepressant after a depression diagnosis simultaneously initiated benzodiazepine therapy, increasing from 6.1% in 2001 and peaking at 12.5% in 2012. We observed no clinically meaningful difference in antidepressant treatment length between simultaneous new users and non–simultaneous new users. Overall, 12.3% of simultaneous new users became long-term benzodiazepine users, an outcome more common among patients with an initial prescription for a longer benzodiazepine days' supply or long-acting benzodiazepine and recent prescription opioid fills.

Our prevalence estimates for simultaneous new use are similar to those reported in the other US population–based study that examines this question in a cohort of veterans with depression. Whether the increase in simultaneous new use of benzodiazepines that we observed is related to the general increase in benzodiazepine use in the US population is unclear. Perhaps the 2001 Cochrane publication (and the 2009 update) played a role because it summarized evidence on combined antidepressant and benzodiazepine use and reported increased short-term response and decreased dropout attributable to adverse effects for patients randomized to combined therapy vs an antidepressant alone (although only 1 trial lasted >8 weeks). Another potential factor is increased recognition of co-occurring anxiety in patients with depression. The plateau that we observed in simultaneous new use might be related to increased caution in prescribing benzodiazepines that may have followed publications that enumerated the potential harms of benzodiazepines when used concurrently with opioids. In addition, changes in the use of drugs used for similar indications but distinct from benzodiazepines (ie, z drugs) might have influenced observed trends in simultaneous new use of benzodiazepines.

Although the trends from 2001 to 2014 were observed across all physician types, adults diagnosed with depression by a psychiatrist were more likely to simultaneously begin new use of an antidepressant and a benzodiazepine than were adults diagnosed by other physicians. The difference between physician type might be related to psychiatrists’ increased familiarity with benzodiazepines, treatment preferences, and training; the severity of their patient’s depression or comorbid anxiety; or the possibility that patients diagnosed by psychologists are more likely to receive prescriptions from another physician because of prescribing restrictions. On the basis of proxies for depression severity available in our data, simultaneous new use may well be more common for patients with more severe depression. Because we lack direct depression severity measures, this remains speculative.

Observational studies have reported increased continuation of antidepressant therapy in patients with benzodiazepine use, similar to findings from the Cochrane review. A study of patients taking antidepressants with prior benzodiazepine use (but not specifically simultaneous new use) reported improved antidepressant therapy continuation at 1 month but without significant differences thereafter. A study in veterans found that simultaneous new users were more likely to have adequate acute-phase antidepressant treatment (first 90 days) compared with patients who started use of an antidepressant without a benzodiazepine. Although we cannot measure early discontinuation of antidepressant treatment during a prescription period because we rely on dispensed prescriptions and the exact time of discontinuation after the dispensing of the last prescription is unknown, antidepressant treatment continuation was similar in simultaneous new users and non–simultaneous new users.

When prescribed carefully in appropriate patients, benzodiazepines are considered to be useful medications. Still, the decision to simultaneously initiate benzodiazepine therapy at antidepressant therapy initiation and the preference for short-term treatment are influenced by concerns about benzodiazepines, including dependency, emergency department visits, and increased risk of fractures, motor vehicle crashes, and overdose. Although most benzodiazepine use among our population was in line with recommendations for short-term use, 12.3% of simultaneous new users became long-term benzodiazepine users (22.0% when allowing for more sporadic benzodiazepine use). In the Veterans Health Administration study, 14.1% of 3320 simultaneous new users continued benzodiazepine treatment for 1 year, more than twice our estimate of 5.7%. Almost one-third of long-term benzodiazepine users in our study had an index depression diagnosis from a psychiatrist, similar to findings of another US study (adults aged 18-64 years) in which 20% to 33% of all long-term benzodiazepine users received at least 1 benzodiazepine prescription from a psychiatrist. More emphasis on short-term use may be needed for some patients, including patients treated by non–mental health specialists.

In our study, strong determinants of long-term benzodiazepine use included potentially modifiable characteristics of the initial regimen (eg, days’ supply of the initial benzodiazepine prescription and use of long-acting agents). Future studies should focus on better understanding how days’ supply and long-acting agents contribute to prolonged benzodiazepine use. Although we did not look at whether opioid use was continued after simultaneous antidepressant and benzodiazepine new use, the association between a recent baseline opioid prescription and long-term benzodiazepine use is particularly concerning because of the known risks of concurrent use of these substances and their pharmacologic interactions.

Limitations

Some limitations should be considered. Our estimates are based on dispensed prescriptions, and we cannot account for patients who were prescribed but did not fill the benzodiazepine prescription and patients who did not actually take the dispensed medications. However, irrespective of whether the medication was taken, our results focus on the clinically relevant questions surrounding coprescribing. We used the most restrictive definition of simultaneous new use in primary analyses (prescriptions filled on the same day) and, therefore, may have underestimated clinically relevant simultaneous new use. However, trends and determinants were consistent under the more liberal definition. We restricted our study to patients who started antidepressant treatment, but some could have been treated with antidepressants in the more remote past; it is possible that prior treatment experiences not captured influenced simultaneous new use decisions. Additional unknown details surrounding benzodiazepine prescriptions include whether they were prescribed as needed and how many refills were allowed. Parameter estimates from our multivariable models of simultaneous new use and long-term benzodiazepine use should not be interpreted causally. In addition, our observation of no meaningful difference in antidepressant treatment length by simultaneous new use could be attributable to unmeasured confounding (eg, depression severity), misclassification, or chance.

Because we required at least a year of continuous coverage in the same health insurance plan, we could have induced a selection bias. It is possible, albeit unlikely, that those who did not meet these requirements differ in their benzodiazepine use patterns from those who we studied. Other factors that influence the generalizability include our decision to exclude patients with recorded baseline substance abuse and select psychiatric comorbidities. In addition, trends present in our data could be influenced by the underlying insurance plans that contribute to MarketScan, which varied from 2001 to 2014. Last, we cannot be certain that the antidepressant treatment was initiated for depression because of the many indications for antidepressants or that the antidepressant prescriber also prescribed the benzodiazepine. However, although MarketScan data cannot identify the physician associated with dispensed prescriptions, preliminary results in a validation study reveal that the physician who diagnosed the index depression is a good proxy for the physician of the initial antidepressant prescription and that most simultaneous new users received both prescriptions from the same physician (G.A.B., unpublished data, May 1, 2017).

Conclusions

Between 2001 and 2014, 10.6% of commercially insured adults with depression who started taking an antidepressant simultaneously started benzodiazepine therapy, with approximately twice the proportion simultaneous starting benzodiazepine treatment by the end of the study period. No clinically meaningful difference was observed in antidepressant treatment continuation in simultaneous new users compared with non–simultaneous new users. Because of the risks associated with benzodiazepines and the potentially modifiable factors associated with long-term use among simultaneous new users, the decision to simultaneously initiate benzodiazepine therapy at antidepressant therapy initiation and the benzodiazepine regimen require careful consideration of potential benefits and harms.

eFigure 1. Proportion of Simultaneous New Users of an Antidepressant and a Benzodiazepine by Age at Antidepressant Treatment Initiation

eFigure 2. Proportion of Antidepressant and Benzodiazepine Simultaneous New Users Who Became Long-term Benzodiazepine Users

eTable 1. Characteristics of Simultaneous Antidepressant and Benzodiazepine New Users and Non-Simultaneous Antidepressant New Users With Depression and Factors Associated With Simultaneous New Use

eTable 2. Details of the Initial Benzodiazepine Prescription Among Antidepressant and Benzodiazepine Simultaneous New Users: Overall and by Selected Physicians

eTable 3. Long-term Benzodiazepine Use Among Simultaneous New Users by Baseline Patient Characteristics and Initial Prescription Details (Full List of Characteristics)

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furukawa TA, Streiner DL, Young LT, Kinoshita Y. Antidepressant plus benzodiazepine for major depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;2(2):CD001026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith WT, Londborg PD, Glaudin V, Painter JR; Summit Research Network . Is extended clonazepam cotherapy of fluoxetine effective for outpatients with major depression? J Affect Disord. 2002;70(3):251-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youssef NA, Rich CL. Does acute treatment with sedatives/hypnotics for anxiety in depressed patients affect suicide risk? a literature review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20(3):157-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin DS, Aitchison K, Bateson A, et al. . Benzodiazepines: risks and benefits: a reconsideration. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(11):967-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lader M. History of benzodiazepine dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1991;8(1-2):53-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson JR. Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines in America and Europe. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(suppl E1):e04. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition). Leicester, England: British Psychological Society; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subramaniam M, He VY, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Chong SA. Prevalence of and factors related to the use of antidepressants and benzodiazepines: results from the Singapore Mental Health Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawada N, Uchida H, Suzuki T, et al. . Persistence and compliance to antidepressant treatment in patients with depression: a chart review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demyttenaere K, Bonnewyn A, Bruffaerts R, et al. . Clinical factors influencing the prescription of antidepressants and benzodiazepines: results from the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders (ESEMeD). J Affect Disord. 2008;110(1-2):84-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caughey GE, Roughead EE, Shakib S, McDermott RA, Vitry AI, Gilbert AL. Comorbidity of chronic disease and potential treatment conflicts in older people dispensed antidepressants. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):488-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardarsdottir H, Egberts AC, van Dijk L, Sturkenboom MC, Heerdink ER. An algorithm to identify antidepressant users with a diagnosis of depression from prescription data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(1):7-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, Sredl K. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(12):1128-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu CS, Shau WY, Chan HY, Lai MS. Persistence of antidepressant treatment for depressive disorder in Taiwan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbing-Karahagopian V, Souverein PC, Korevaar JC, et al. . Concomitant medication use and its implications on the hazard pattern in pharmacoepidemiological studies: example of antidepressants, benzodiazepines and fracture risk. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health. 2015;12(3):e11273. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neutel CI. The epidemiology of long-term benzodiazepine use. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17(3):189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dijk KN, de Vries CS, ter Huurne K, van den Berg PB, Brouwers JR, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Concomitant prescribing of benzodiazepines during antidepressant therapy in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(10):1049-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeiffer PN, Ganoczy D, Zivin K, Valenstein M. Benzodiazepines and adequacy of initial antidepressant treatment for depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(3):360-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen RA, Martinez ME Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/releases.htm. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- 21.Kurko TA, Saastamoinen LK, Tähkäpää S, et al. . Long-term use of benzodiazepines: definitions, prevalence and usage patterns—a systematic review of register-based studies. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(8):1037-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolton JM, Metge C, Lix L, Prior H, Sareen J, Leslie WD. Fracture risk from psychotropic medications: a population-based analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(4):384-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, neuroleptics and the risk of fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(6):807-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS. Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: case-cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD. Polydrug abuse: a review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1-2):8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorevski E, Bian B, Kelton CM, Martin Boone JE, Guo JJ. Utilization, spending, and price trends for benzodiazepines in the US Medicaid program: 1991-2009. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(4):503-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, Starrels JL. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996–2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kao MC, Zheng P, Mackey S Trends in benzodiazepine prescription and co-prescription with opioids in the United States, 2002–2009. Paper presented at: 2014 AAPM Annual Meeting; July 24, 2014; Austin, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Depp CA, Mojtabai R. Continuing vs new prescriptions for sedative-hypnotic medications: United States, 2005-2012. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):2019-2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [published correction appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(7):709]. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, McDermut W. Major depressive disorder and axis I diagnostic comorbidity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(3):187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen LH, Hedegaard H, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics: United States, 1999–2011. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(166):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegler A, Tuazon E, Bradley O’Brien D, Paone D. Unintentional opioid overdose deaths in New York City, 2005-2010: a place-based approach to reduce risk. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):569-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salzman C. The APA Task Force report on benzodiazepine dependence, toxicity, and abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(2):151-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration The DAWN Report: Benzodiazepines in Combination with Opioid Pain Relievers or Alcohol: Greater Risk of More Serious ED Visit Outcomes. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takkouche B, Montes-Martínez A, Gill SS, Etminan M. Psychotropic medications and the risk of fracture: a meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2007;30(2):171-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbone F, McMahon AD, Davey PG, et al. . Association of road-traffic accidents with benzodiazepine use. Lancet. 1998;352(9137):1331-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited: will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106(12):2086-2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westreich D, Greenland S. The table 2 fallacy: presenting and interpreting confounder and modifier coefficients. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(4):292-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong J, Motulsky A, Eguale T, Buckeridge DL, Abrahamowicz M, Tamblyn R. Treatment indications for antidepressants prescribed in primary care in Quebec, Canada, 2006-2015. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2230-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Proportion of Simultaneous New Users of an Antidepressant and a Benzodiazepine by Age at Antidepressant Treatment Initiation

eFigure 2. Proportion of Antidepressant and Benzodiazepine Simultaneous New Users Who Became Long-term Benzodiazepine Users

eTable 1. Characteristics of Simultaneous Antidepressant and Benzodiazepine New Users and Non-Simultaneous Antidepressant New Users With Depression and Factors Associated With Simultaneous New Use

eTable 2. Details of the Initial Benzodiazepine Prescription Among Antidepressant and Benzodiazepine Simultaneous New Users: Overall and by Selected Physicians

eTable 3. Long-term Benzodiazepine Use Among Simultaneous New Users by Baseline Patient Characteristics and Initial Prescription Details (Full List of Characteristics)