Key Points

Questions

Can urinary testing of prostate cancer–associated RNA (PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG) improve detection of aggressive prostate cancer (Gleason score, ≥7), and how would such testing affect health care costs?

Findings

In this prospective diagnostic study of 1077 men, urinary RNA parameters that significantly improved specificity for predicting prostate cancer were identified in the developmental cohort and improvement of specificity for predicting aggressive cancer (33% vs 17%) was confirmed in a validation cohort. Potential health care cost savings were shown by modeling the effect of urinary PCA3 and TMPRSS22:ERG testing.

Meaning

Urinary testing for TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 can avert unnecessary biopsy with consequent potential health care cost savings.

Abstract

Importance

Potential survival benefits from treating aggressive (Gleason score, ≥7) early-stage prostate cancer are undermined by harms from unnecessary prostate biopsy and overdiagnosis of indolent disease.

Objective

To evaluate the a priori primary hypothesis that combined measurement of PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG (T2:ERG) RNA in the urine after digital rectal examination would improve specificity over measurement of prostate-specific antigen alone for detecting cancer with Gleason score of 7 or higher. As a secondary objective, to evaluate the potential effect of such urine RNA testing on health care costs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective, multicenter diagnostic evaluation and validation in academic and community-based ambulatory urology clinics. Participants were a referred sample of men presenting for first-time prostate biopsy without preexisting prostate cancer: 516 eligible participants from among 748 prospective cohort participants in the developmental cohort and 561 eligible participants from 928 in the validation cohort.

Interventions/Exposures

Urinary PCA3 and T2:ERG RNA measurement before prostate biopsy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Presence of prostate cancer having Gleason score of 7 or higher on prostate biopsy. Pathology testing was blinded to urine assay results. In the developmental cohort, a multiplex decision algorithm was constructed using urine RNA assays to optimize specificity while maintaining 95% sensitivity for predicting aggressive prostate cancer at initial biopsy. Findings were validated in a separate multicenter cohort via prespecified analysis, blinded per prospective-specimen-collection, retrospective-blinded-evaluation (PRoBE) criteria. Cost effects of the urinary testing strategy were evaluated by modeling observed biopsy results and previously reported treatment outcomes.

Results

Among the 516 men in the developmental cohort (mean age, 62 years; range, 33-85 years) combining testing of urinary T2:ERG and PCA3 at thresholds that preserved 95% sensitivity for detecting aggressive prostate cancer improved specificity from 18% to 39%. Among the 561 men in the validation cohort (mean age, 62 years; range, 27-86 years), analysis confirmed improvement in specificity (from 17% to 33%; lower bound of 1-sided 95% CI, 0.73%; prespecified 1-sided P = .04), while high sensitivity (93%) was preserved for aggressive prostate cancer detection. Forty-two percent of unnecessary prostate biopsies would have been averted by using the urine assay results to select men for biopsy. Cost analysis suggested that this urinary testing algorithm to restrict prostate biopsy has greater potential cost-benefit in younger men.

Conclusions and Relevance

Combined urinary testing for T2:ERG and PCA3 can avert unnecessary biopsy while retaining robust sensitivity for detecting aggressive prostate cancer with consequent potential health care cost savings.

This study evaluates the potential of urinary testing for TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 RNA to improve detection of aggressive prostate cancer and reduce health care costs.

Introduction

Ample evidence has shown survival benefits associated with treatment of intermediate- and high-risk, early-stage prostate cancer. Low specificity of tests for serum levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA), however, has limited its utility for prostate cancer screening. Strategies are needed for detecting cancers with more aggressive features (Gleason score, ≥7) to enable survival benefits from treatment while limiting unnecessary biopsies and overdetection of indolent disease.

Gene expression alterations in prostate cancer representing an opportunity to refine early detection include overexpression of PCA3, a noncoding RNA, and aberrant TMPRSS2:ERG (T2:ERG) expression, which results from a prostate cancer–specific chromosomal rearrangement on chromosome 21 that juxtaposes the 5′ untranslated region of TMPRSS2 to the ERG oncogene. In contrast, PSA is expressed in normal and cancerous prostate cells alike, limiting its specificity for cancer.

Following development of clinical assays for detecting PCA3 and T2:ERG in urine, we sought to determine whether measuring these prostatic RNAs could improve specificity for detecting aggressive prostate cancer. We assembled a prospective multicenter cohort to develop a method of combining PCA3 and T2:ERG urine assay results via an “either-or” logic for a decision algorithm to select men for initial biopsy, and then we validated this decision algorithm in a separate, multicenter cohort via prespecified analysis blinded per prospective-specimen-collection, retrospective-blinded-evaluation (PRoBE) criteria. We then evaluated effects of such multiplex urine testing on costs of prostate cancer early detection.

Methods

Participants

The developmental cohort consisted of prospectively enrolled participants at 4 urology groups affiliated with 3 academic medical centers (Dana Farber Harvard Cancer Center; Cornell University; and University of Michigan) comprising a National Cancer Institute Early Detection Research Network (NCI-EDRN) Clinical Validation Center (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Eligibility was restricted to men planning to undergo first-time prostate biopsy, who signed informed consent (approved by the respective institutional review board) and provided post-urinary specimens after digital rectal examination (DRE) but before biopsy. Exclusion criteria were previously diagnosed prostate cancer, prior prostate biopsy, previous prostatectomy, other cancer diagnosis, or inability to provide post-DRE urine sample.

The validation cohort consisted of participants in the NCI-EDRN’s Urinary PCA3 Evaluation Trial that enrolled men prior to prostate biopsy at 11 sites with eligibility as previously described. Additional eligibility criteria for the validation cohort analysis in the present study included completion of prostate biopsy, availability of biorepository sample to assay urinary T2:ERG expression, and no prior prostate biopsy (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The protocol proscribed routine clinical transrectal ultrasonogram–guided prostate biopsy; 87% of participants had 12 biopsy cores sampled.

Urine Assay

First-catch urine was collected after DRE, admixed with RNA stabilization buffer, and frozen to −80°C within 4 hours of collection. Developmental cohort specimens were transported to the CLIA laboratory (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments) at University of Michigan for transcription-mediated amplification quantitative T2:ERG and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Progensa PCA3 assay (Hologic Inc). Urine specimen collection was performed similarly in the multicenter validation cohort, and T2:ERG and PCA3 assays were performed by the EDRN Biomarker Reference Laboratory at Johns Hopkins. A random sample subset was independently analyzed at Hologic Inc as a quality control. Assay laboratories were blinded to prostate biopsy results.

Analysis

For both cohorts, the a priori primary end point was presence vs absence of aggressive prostate cancer (Gleason score, ≥7) on biopsy, where absence included both indolent (Gleason score, ≤6) and no (negative biopsy findings) cancers. Assignment of Gleason score was by local clinical pathology evaluation; a randomly selected subset of the validation cohort had undergone quality review of the cancer diagnosis by a central pathologist.

A clinical decision algorithm to restrict prostate biopsy was derived from the developmental cohort (n = 516), locked-down, and sensitivity and specificity were then evaluated in the validation cohort (n = 561). In the developmental cohort, we used an “OR” rule; ie, the test result was considered positive if 1 of the 3 biomarkers (serum PSA, T2:ERG, or PCA3) was above its normal threshold. This multiplex decision rule and the cutoff points for PSA, T2-ERG, and PCA3 were determined by a grid search to maximize specificity for the combined group of indolent and no cancers, while setting its sensitivity at 95% or higher for aggressive cancers. Optimal thresholds of urinary T2:ERG and PCA3 scores were rounded to integers (T2:ERG score, >8; PCA3 score, >20). The final threshold for serum PSA of greater than 10 ng/mL incorporated evidence supporting treatment of cancer with PSA higher than 10 ng/mL even though in the developmental cohort, all patients with PSA higher than 10 ng/mL had either a T2:ERG score higher than 8 or a PCA3 score higher than 20.

After the multiplex decision algorithm was locked down, validation cohort data were accessed to posit the primary hypothesis of whether the predefined decision algorithm would improve specificity for detecting prostate cancer with a Gleason score of 7 or higher and to estimate sensitivity of this decision rule. To test whether the multiplex decision rule has superior specificity to PSA alone, the decision rule from the training set was locked down and evaluated on the validation set. A total of 10 000 bootstrap samples were generated to obtain the variance and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference of the specificities between the 2 decision rules on the validation set. For each bootstrap sample, sensitivity and specificity were calculated by the prespecified, locked-down decision rule, then again by PSA alone, and the difference in specificities (multiplex decision algorithm minus PSA alone) were calculated. The variance of this difference and its 95% CI were obtained from the 10 000 bootstrap differences. The null hypothesis of no superiority of the multiplex decision ruler over PSA alone would be rejected at a 1-sided α = .05 if the lowest fifth percentile of 10 000 differences was greater than 0.

We note that the power attained with the available sample size using either the empirical receiver operating curve (ROC) for PSA and a kernel-based ROC for PSA is 83.5% and 85.0%, respectively for detecting significant differences in specificities (eAppendix, A in the Supplement).

As detailed and supported in the eAppendix, B in the Supplement, post hoc significant association was observed between results of the urinary PCA3-T2:ERG assay and the dichotomized PSA test (<10 ng/mL or >10 ng/mL) in the developmental cohort (Fisher exact test P = .01) but not in the validation cohort (P = .09).

Cost Analysis

A decision analytic model was developed to compare the multiplex decision algorithm using serum PSA and urinary markers vs standard care among patients with positive PSA screens under 3 scenarios: (1) no biopsies prompted by abnormal PSA (ie, strict adherence to US Protective Services Task Force [USPSTF] recommendations), (2) biopsy based on abnormal PSA or DRE findings, and (3) biopsy restricted by the multiplex urinary marker decision algorithm. We modeled a 1-time test with the multiplex urinary marker decision algorithm. We did not consider repeated screening or testing. We projected the number of biopsies, the number of patients diagnosed with metastatic cancer, and lifetime health care costs under each strategy. Projecting quality-adjusted life-years is left for future work.

The first scenario represents care men would receive under USPSTF prostate cancer screening guidelines, which recommend against PSA screening. In this setting, physicians would not know if a patient had an abnormal PSA level nor if a patient had asymptomatic, early-stage prostate cancer in the first place, and prostate cancer care would be limited to treatment of advanced, symptomatic disease. The second scenario corresponds to common practice prior to the release of the current USPSTF recommendation—ie, biopsy based on abnormal PSA or DRE findings, as in our developmental cohort, consistent with National Comprehensive Care Network guidelines. We assumed that men who undergo biopsy receive effective care to prevent disease progression. In the third scenario, patients found to have elevated serum PSA levels undergo biopsy based on testing positive on either T2:ERG or PCA3 or registering a serum PSA level higher than 10 ng/mL. The model considers how incorporating PCA3 and T2:ERG into the diagnostic pathway affects the decision to undergo biopsy and treatment.

We obtained parameter values for sensitivity and specificity from the developmental cohort and tumor progression rates and cost estimates from the literature. Estimates of the costs incurred by patients diagnosed with cancer represent lifetime, stage-specific, prostate cancer–related costs based on an analysis of Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with prostate cancer between 1991 and 2002, regardless of treatment approach. These estimates represent costs to the Medicare program and reflect treatment patterns and cure rates for beneficiaries diagnosed during this period. We assumed that the cost of a biopsy, inclusive of biopsy-related complications, is $2300. We use enzalutamide as a stand-in for treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), and sensitivity analysis estimated the impact on costs if varying percentages of men received systemic therapy for CRPC. The cost of enzalutamide was based on the Medicare reimbursement rate and the median duration of treatment in the drug’s phase 3 trial. Because the cost of a commercially available T2:ERG and PCA3 test has not yet been established, we did not include this cost in our analysis. We discounted costs for late-stage disease by 3% per year, assuming that they occur 5 years in the future. We assumed all other costs are incurred in a short timeframe (ie, less than a year). All costs are stated in 2013 dollars (additional model details are provided in eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Results

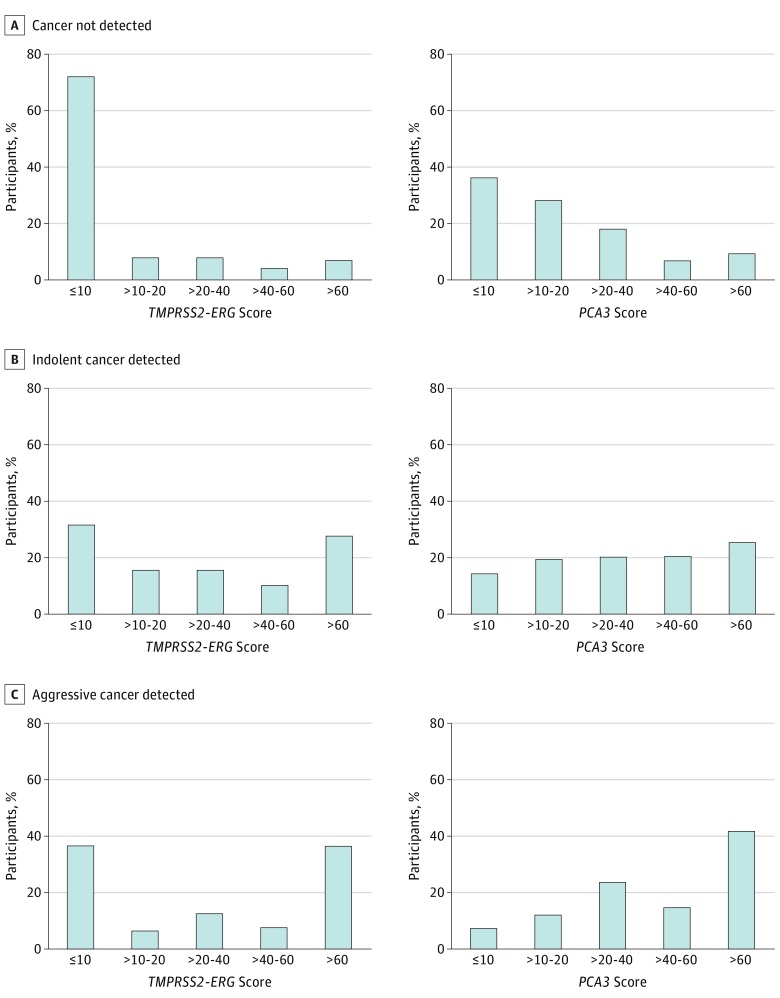

A total of 516 participants met inclusion criteria (ie, men presenting for first-time prostate biopsy) in the EDRN Clinical Validation Center, and these make up the developmental cohort (Table 1; eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Clinical factors associated with aggressive prostate cancer (Gleason score, ≥7) included older age (P < .001) and abnormal or suspect findings on DRE (P = .03). Urine T2:ERG and PCA3 scores of greater than 60 were each significantly associated with aggressive prostate cancer (P < .001 for both; see the Figure).

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants in 516 Patients in the Developmental Cohort.

| Participant Characteristica | Diagnosis Based on Prostate Biopsy, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Cancer | Indolent Cancer (Gleason Score ≤6) | Aggressive Cancer (Gleason Score ≥7) | Total | |

| Total, No. (%) | 262 (50.8) | 98 (18.99) | 156 (30.23) | 516 (100) |

| Age, mean (range), y | 60 (33-79) | 62 (47-84) | 64 (43-85)b,c,d | 62 (33-85) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 210 (80.46) | 82 (83.67) | 126 (80.77) | 418 (81.2) |

| Black | 24 (9.2) | 8 (8.16) | 20 (12.82) | 52 (10.1) |

| Asian | 14 (5.36) | 3 (3.06) | 1 (0.64) | 18 (3.5) |

| Other | 13 (4.98) | 5 (5.10) | 9 (5.77) | 27 (5.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino ethnicity | ||||

| Yes | 12 (4.58) | 4 (4.08) | 6 (3.85) | 22 (4.3) |

| Smoking status, ever smoked | 113 (63.48) | 42 (59.15) | 72 (60.5) | 227 (61.7) |

| Family history of prostate cancer | 62 (23.75) | 25 (25.51) | 32 (20.78) | 119 (23.2) |

| DRE results | ||||

| Normal | 67 (25.57) | 18 (18.37) | 42 (27.10) | 127 (24.7) |

| Enlarged/benign | 163 (62.21) | 68 (69.39) | 74 (47.74) | 305 (59.2) |

| Abnormal/suspect | 30 (11.45) | 12 (12.24) | 38 (24.52)b,c,d | 80 (15.5) |

| Prebiopsy serum PSA, median (range), ng/mL | 4.5 (0.3-22.2) | 5.0 (0.8-25.6) | 5.6 (1.1-460.4)b,c,d | 4.8 (0.3-460.4) |

| Prebiopsy urinary PCA3 score, median (range) | 14.2 (0.3-158.1) | 36.6 (2.1-174.9) | 47.5 (2.3-313.5)b,c,d | 24.6 (0.3-313.5) |

| Prebiopsy urinary TMPRSS2:ERG score, median (range) | 1.7 (0-1467.1) | 21.8 (0-919.5) | 32.0 (0-6031.6)b,c | 7.4 (0-6031.6) |

Abbreviations: DRE, digital rectal examination; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Continuous variables evaluated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test, categorical variables by Fisher exact or Freeman-Halton test.

Significant difference for Gleason ≥7 vs no cancer.

Significant difference for Gleason ≥7 vs no cancer and indolent combined (no aggressive prostate cancer).

Significant difference for Gleason ≥7 vs Gleason ≤6 cancer.

Figure. Distribution of Urinary TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 RNA Assay Results in 516 Patients in the Developmental Cohort by Tissue Diagnosis.

Because T2:ERG gene fusion expression occurs in a subset of prostate cancers, our primary hypothesis posited that combining urine T2:ERG with PCA3 assay in “either-or” multiplex combinatorial logic would improve the specificity of predicting aggressive (Gleason score, ≥7) prostate cancer. Urine T2:ERG testing showed limited utility when optimized for higher than 95% sensitivity, as expected, given that T2:ERG gene fusions are only present in about half of prostate cancers (Figure and Table 2). Assays for PSA and PCA3 yielded specificities of 18% and 17%, respectively, at 95% sensitivity for aggressive prostate cancer (Table 2). Combining urinary T2:ERG with PCA3 testing improved specificity of predicting aggressive prostate cancer to 39% (at optimized cut points of a T2:ERG score of 7.6 and a PCA3 score of 19.1; Table 2). In this cohort, every patient with a PSA level higher than 10 ng/mL had either a T2:ERG score greater than 7.6 or a PCA3 score greater than 19.1.

Table 2. Combining Urinary TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 Measurement to Improve Specificity of Predicting Aggressive Prostate Cancer (Gleason Score ≥7).

| Diagnostic Biomarkera | Developmental Cohort (n = 516) |

PPV, % (95% CI) (Observed Prevalence, 26.38%) |

NPV, % (95% CI) (Observed Prevalence, 26.38%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥95% Sensitivity Threshold | Gleason ≥7 Sensitivity, % (95% CI) (n = 156) |

No Cancer or Gleason ≤6 Specificity, % (95% CI) (n = 360) |

|||

| PSA | 3.0 | 96.2 (93.2-99.2) | 18.1 (14.1-22.1) | 29.6 (28.4-30.8) | 93.0 (85.4-96.8) |

| PCA3 | 6.3 | 95.5 (92.2-98.7) | 16.9 (13.0-20.8) | 29.2 (28.0-30.4) | 91.3 (83.1-95.7) |

| TMPRSS2:ERGb | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSA or TMPRSS2:ERG | 3.1; 289 | 95.5 (92.2-98.7) | 20.0 (15.9-24.1) | 29.3 (28.7-31.3) | 92.5 (85.4-96.3) |

| PSA or PCA3 | 4.2; 21.2 | 95.5 (92.2-98.7) | 23.6 (19.2-27.9) | 30.9 (29.5-32.4) | 93.6 (87.4-96.9) |

| PCA3 or TMPRSS2:ERGc | 19.1; 7.6 | 95.5 (92.2-98.7) | 39.4 (34.3-44.4) | 36.1 (34.0-38.2) | 96.1 (92.1-98.1) |

| PSA or PCA3 or TMPRSS2:ERG | 10; 19.1; 7.6 | 95.5 (92.2-98.7) | 39.4 (34.3-44.4) | 36.1 (34.0-38.2) | 96.1 (92.1-98.1) |

Abbreviations: NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

PSA is reported in nanograms per milliliter; both TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 are reported as scores.

Because the TMPRSS2:ERG mutation is absent in many cancers, sensitivity above 95% for urinary TMPRSS2:ERG as a stand-alone predictive biomarker is possible only if no cases are excluded based on urinary TMPRSS2:ERG value alone; more than 5% of cases had a TMPRSS2:ERG score of 0.

Including PSA level higher than 10 ng/mL as an a priori trigger did not improve performance of the “TMPRSS2:ERG or PCA3” dual biomarker model in the developmental cohort because we found that all cases of PSA level above 10 ng/mL already exceeded the positive thresholds of urinary PCA3 (score >19.1) or TMPRSS2:ERG (score >7.6).

We next sought to validate whether combining urinary T2:ERG and PCA3 measurement improves specificity of predicting aggressive prostate cancer via analysis of a separate 561-patient multicenter validation cohort assayed at an independent laboratory (eTable 1 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Based on developmental cohort results, thresholds of T2:ERG score greater than 8, PCA3 score greater than 20, or serum PSA level greater than 10 ng/mL as a positive test result were prespecified for the validation analysis. The validation analysis confirmed that overexpression of either urine T2:ERG or PCA3 or PSA level higher than 10 ng/mL improved prediction of aggressive prostate cancer by increasing specificity from 17% to 33% compared with serum PSA level alone while attaining high sensitivity (Table 3) (difference in specificities, 17%; lower 95% CI boundary, 0.73%; P = .04). Post hoc analysis using a method of kernel estimators, we found 2-sided P = .01 and 1-tailed P = .007 (detailed in eAppendix, C in the Supplement). In exploratory analysis, we evaluated the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) calculator for high-grade disease in this validation cohort, then used logistic regression to add PCA3 and T2:ERG and evaluated differences in consequent areas under the curve (AUCs) by the Delong test. The PCPT model AUC was 0.74 (95% CI, 0.70-0.79), whereas for PCPT plus T2:ERG and PCA3, the AUC was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.77-0.85) (P < .001). At 95% sensitivity, the specificity for PCPT in predicting prostate cancer with a Gleason score of 7 or higher was 31%; it was 37% for PCPT combined with PCA3 and T2:ERG measurement.

Table 3. Validation of Multiplex Algorithm Including Urinary TMPRSS2:ERG, PCA3, and Serum PSA Level Higher Than 10 ng/mL to Improve Specificity of Predicting Aggressive Prostate Cancer (Gleason Score ≥7).

| Diagnostic Biomarkera | Validation Cohort (n = 561) |

PPV, % (95% CI) (Observed Prevalence, 26.38%) |

NPV, % (95% CI) (Observed Prevalence, 26.38%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold Value | Gleason ≥7 Sensitivity, % (95% CI) (n = 148) |

No Cancer or Gleason ≤6 Specificity, % (95% CI) (n = 413) |

|||

| PSA | 3 | 91.2 (86.6-95.8) | 16.7 (13.1-20.3) | 28.2 (28.9-29.5) | 84.1 (75.1-90.3) |

| PCA3 | 7 | 96.6 (93.7-99.5) | 18.4 (14.7-22.1) | 29.8 (28.6-30.9) | 93.8 (86.2-97.3) |

| TMPRSS2:ERG | 0b | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSA or TMPRSS2:ERG | 4; 289 | 85.8 (80.2-91.4) | 34.1 (29.5-38.7) | 31.8 (29.3-33.9) | 87.0 (81.5-91.1) |

| PSA or PCA3 | 5; 22 | 90.5 (85.8-95.2) | 32.2 (27.7-36.7) | 32.5 (30.5-34.2) | 90.4 (84.9-94.1) |

| PCA3 or TMPRSS2:ERG | 20; 8 | 90.5 (85.8-95.2) | 35.4 (30.8-40.0) | 33.4 (31.5-35.4) | 91.2 (86.1-94.6) |

| PSA or PCA3 or TMPRSS2:ERGc | 10; 20; 8 | 92.6 (88.4-96.8) | 33.4 (28.8-37.9) | 33.2 (31.4-35.1) | 92.6 (87.5-95.8) |

Abbreviations: NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

PSA is reported in nanograms per milliliter; both TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 are reported as scores.

Threshold set as TMPRSS2:ERG score of 0 or higher to include cases in which TMPRSS2:ERG score is 0.

The rule combining PSA ≥ 10 ng/mL, PCA3 score ≥ 20, and TMPRSS2:ERG score ≥ 8 was prespecified as the primary decision algorithm to be tested by the validation analyses per prospective-specimen-collection, retrospective-blinded-evaluation (PRoBE) criteria. Observed specificity and sensitivity for the individual markers or dual combinations at these threshold values are shown for completeness and to provide context for interpretation of the 3-biomarker rule. When PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG were analyzed as continuous variables in the logistic regression model (separately from clinical decision-targeting “OR” combinatorial logic that was the focus of validating the prespecified thresholds following PRoBE design), receiver operating curve plots of the individual biomarkers’ accuracy in predicting prostate cancer with Gleason score of 7 or higher showed the following area under the curve values: PSA, 0.67; PCA3, 0.71; and TMPRSS2:ERG, 0.66. The corresponding area under the curve value for multivariable logistic regression combining PCA3 and TMPRSS2:ERG was 0.75, while the area under the curve value for combining PCA3, TMPRSS2:ERG, and PSA was 0.77,

Restricting biopsy to participants with positive urinary findings of T2:ERG or PCA3 or PSA level higher than 10 ng/mL in the validation cohort would have avoided 42% of unnecessary biopsies (true negative, 124 of 297 biopsies in men with no cancer found on biopsy) and would have avoided overdetection of 12% of indolent cancers (true negative, 14 of 116 biopsies in men having a Gleason score of ≤6). Overall, 33% of “excessive” prostate biopsies would be avoided by the multiplex decision algorithm (true negative, 138 of 413 biopsies in men having no cancer or prostate cancer with a Gleason score of ≤6). Among participants with Gleason scores of 7 or higher, only 7% would be missed under the combined thresholds (false negative, 11 of 148) compared with 21% (false negative, 31 of 148) when using a PCA3 threshold greater than 20 alone.

To gauge the potential cost impact of using of PCA3 and T2:ERG urine testing vs standard care, we modeled the costs of incorporating PCA3 and T2:ERG into the clinical pathway of decision to perform prostate biopsy and consequent prostate cancer care (Table 4 and eFigure 3 in the Supplement). The costs associated with prostate cancer detection by urinary T2:ERG and PCA3 testing (among men with abnormal PSA or DRE findings), which include costs of biopsy and of treating men with early-stage disease, exceed the costs associated with no PSA-prompted biopsies (per UTPSTF recommendations), which include only the costs of treating late-stage disease among men whose tumors progress. The difference varies with age and with the use of second-line systemic therapy for patients with castration-resistant, metastatic disease. Conversely, in comparison with biopsy of all men with abnormal PSA screening results, restricting biopsy using urinary T2:ERG and PCA3 testing yielded cost savings in the range of $1200 to $2100 per patient.

Table 4. Effect of Urinary TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 Testing on Lifetime Cost of Care Among Men With Abnormal Prostate Cancer Screening Resultsa.

| Age, y | Intervention for CRPC, %b | Lifetime Cost of Prostate Cancer Detection Test by Diagnostic Strategy, $c | Cost Differential per Patient for TMPRSS2:ERG or PCA3 Urine Test vs Current Care Standards, $d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USPSTFe | Biopsy Prompted by Abnormal PSA or DRE | PSA/DRE Prompted Biopsy Restricted by PCA3 and T2: ERG | TMPRSS2:ERG + PCA3 + PSA vs USPSTFe | TMPRSS2:ERG + PCA3 + PSA vs Biopsy Prompted by PSA/DRE Alone | ||

| 55-64 | 20 | 12 332 | 26 173 | 24 261 | +11 929 | −1912 |

| 80 | 23 111 | 26 173 | 24 936 | +1825 | −1237 | |

| 65-74 | 20 | 8282 | 26 173 | 24 067 | +15 785 | −2106 |

| 80 | 15 521 | 26 173 | 24 572 | +9051 | −1601 | |

Abbreviations: CRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; DRE, digital rectal examination; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Men being considered for prostate biopsy owing to abnormal PSA or DRE findings.

Interventions for late-stage cancer refer to contemporary, secondary androgen-targeting therapy (eg, enzalutamide).

Costs represent per-patient lifetime costs relative to matched noncancer controls.

Positive value (plus sign) designates greater cost for decision algorithm using the TMPRSS2:ERG + PCA3 urine test; negative value (minus sign) designates lower cost.

USPSTF, US Protective Services Task Force recommendations (ie, no PSA or DRE evaluation and no biopsy).

Discussion

A pivotal flaw in relying on serum PSA to select men for prostate biopsy is low specificity for detecting aggressive prostate cancer at PSA levels having sufficient sensitivity. Herein, we developed and validated a decision algorithm that uses urinary testing for 2 prostate cancer–associated RNA markers, T2:ERG and PCA3, to improve the specificity for detecting aggressive prostate cancer among men with elevated PSA or abnormal DRE findings. The validated “either/or” algorithm, where biopsy is prompted by high expression of either urinary RNA marker, would reduce excess biopsy while preserving detection of aggressive prostate cancers (Gleason score, ≥7).

The T2:ERG gene fusion is present in two-thirds of prostate cancers and is consequently suitable for combination with other biomarkers in decision algorithms. Even though the presence of T2:ERG is not associated with prostate cancer aggressiveness, prior studies have shown association between urine T2:ERG score and total ERG-positive tumor burden, indirectly reflecting tumor aggressiveness. Accordingly, we observed association between urinary T2:ERG score and presence of cancer having a Gleason of 7 or higher (Figure). However, a low T2:ERG score does not exclude the possibility of aggressive cancer (since one-third of prostate cancers lack the mutation), and so T2:ERG testing would be more effective if combined with other markers.

It has been shown that PCA3 is a noncoding RNA expressed at higher levels in men with prostate cancer than in those with normal prostate. The Progensa PCA3 assay has been FDA approved to help identify men who do not require a repeat biopsy. Use of PCA3 testing can improve predictive accuracy for cancer on initial biopsy; however, at high sensitivity, PCA3 specificity as a stand-alone test is limited (Table 2). Optimizing the potential for urinary PCA3 testing to improve selecting men for initial prostate biopsy may hinge on combining PCA3 with other biomarkers, such as T2:ERG.

We constructed a clinical algorithm combining T2:ERG with PCA3 via either-or combinatorial logic. To accommodate the survival benefit of treating prostate cancers in patients having serum PSA levels greater than 10 ng/mL, this PSA threshold was also incorporated in the predictive models a priori. Our findings confirm the hypothesis that combining T2:ERG, PCA3, and PSA measurement would reduce unnecessary prostate biopsy and overdiagnosis while preserving detection of aggressive cancers. These findings extend those of earlier studies of preclinical reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction assays evaluating T2:ERG and PCA3 in cellular fraction of post-DRE urine. Our group’s prior report, which used an earlier version of the T2:ERG assay and the corresponding “MIPS” test, did not discern the specific clinical scenario of decision about who should undergo initial prostate biopsy and did not evaluate assay thresholds to optimize specificity at high sensitivity for prostate cancer with a Gleason score of 7 or higher.

Cost analysis suggested that, relative to having all men with abnormal PSA levels undergo biopsy, urine PCA3 and T2:ERG testing to select biopsy candidates could reduce cost of prostate cancer detection and consequent care. Relative to USPSTF recommendations (where men would undergo neither PSA testing nor consequent biopsy), urine RNA testing to select men for biopsy would reduce treatment costs for advanced disease, but these were offset by costs of biopsies and care for early-stage prostate cancer.

Limitations

We did not evaluate repeat testing, so our study does not inform the relationship of negative results with cancer detection during subsequent screens. We did not directly evaluate the impact of detection on patients’ length and quality of life. Cost estimates did not include the cost of PCA3 and T2:ERG testing (which does not yet have a designated federal payment rate). These considerations indicate a basis for future studies to examine more recent treatment cost data, the impact of detection on costs for unrelated conditions, repeat screening, and quality-adjusted life years.

Generalizability of the decision algorithm described herein has limitations. The multiplex urinary RNA algorithm was developed and validated in cohorts of men presenting for initial prostate biopsy owing to elevated PSA or abnormal DRE findings, and therefore represents a strategy to refine biopsy decisions after PSA screening rather than replacing PSA testing. In addition, biopsy as primary indicator of cancer aggressiveness is limited by ascertainment bias because a subset of patients may harbor cancer with a Gleason score of 7 or higher missed on biopsy. However, biopsy is the most definitive available prostate cancer diagnostic test. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided biopsy represents an opportunity to reduce ascertainment error due to false-negative biopsy but was not a care standard when our study began, and consensus is still lacking as to MRI role with initial biopsy. Although blood tests such as the Prostate Health Index and 4K Score have been developed to complement total PSA testing, these were not included in our evaluation, and these may be advantageous over the urine test described in this study by not requiring a DRE. Combining urine RNA testing with novel PSA isoform or combination kallikrein tests represents an opportunity for further study.

Conclusions

Nevertheless, our results indicate that urinary PCA3 and T2:ERG testing can improve specificity of predicting aggressive prostate cancer beyond either serum PSA level or either urinary marker alone. Use of these tests to select men for initial biopsy after elevated PSA or abnormal DRE findings showed that 42% of men would have been safely excluded from undergoing unnecessary prostate biopsy, while high sensitivity for aggressive cancer was retained. These findings suggest that urinary RNA testing can mitigate harms of prostate screening while retaining the benefits of identifying aggressive cancers suitable for treatment.

eTable 1. Subject Characteristics in the NCI-EDRN Urinary PC3 Evaluation Trial Validation Cohort

eFigure 1. STARD Study Flow Diagram for Developmental cohort

eFigure 2. STARD Study Flow Diagram for Validation Cohort

eFigure 3. Cost analysis and model assumption details

eAppendix.

References

- 1.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(10):932-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolla M, Gonzalez D, Warde P, et al. Improved survival in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy and goserelin. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(5):295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Amico AV, Manola J, Loffredo M, Renshaw AA, DellaCroce A, Kantoff PW. 6-month androgen suppression plus radiation therapy vs radiation therapy alone for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(7):821-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widmark A, Klepp O, Solberg A, et al. ; Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study 7; Swedish Association for Urological Oncology 3 . Endocrine treatment, with or without radiotherapy, in locally advanced prostate cancer (SPCG-7/SFUO-3): an open randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9660):301-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL III, et al. ; PLCO Project Team . Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1310-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. ; ERSPC Investigators . Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1320-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, et al. ; Prostate Cancer Intervention versus Observation Trial (PIVOT) Study Group . Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(3):203-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bussemakers MJ, van Bokhoven A, Verhaegh GW, et al. DD3: a new prostate-specific gene, highly overexpressed in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59(23):5975-5979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hessels D, Klein Gunnewiek JM, van Oort I, et al. DD3(PCA3)-based molecular urine analysis for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2003;44(1):8-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks LS, Fradet Y, Deras IL, et al. PCA3 molecular urine assay for prostate cancer in men undergoing repeat biopsy. Urology. 2007;69(3):532-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gittelman MC, Hertzman B, Bailen J, et al. PCA3 molecular urine test as a predictor of repeat prostate biopsy outcome in men with previous negative biopsies: a prospective multicenter clinical study. J Urol. 2013;190(1):64-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei JT, Feng Z, Partin AW, et al. Can urinary PCA3 supplement PSA in the early detection of prostate cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4066-4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310(5748):644-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narod SA, Seth A, Nam R. Fusion in the ETS gene family and prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(6):847-851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomlins SA, Aubin SM, Siddiqui J, et al. Urine TMPRSS2:ERG fusion transcript stratifies prostate cancer risk in men with elevated serum PSA. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(94):94ra72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pepe MS, Feng Z, Janes H, Bossuyt PM, Potter JD. Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: standards for study design. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(20):1432-1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephan C, Jung K, Semjonow A, et al. Comparative assessment of urinary prostate cancer antigen 3 and TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion with the serum [-2]proprostate-specific antigen-based prostate health index for detection of prostate cancer. Clin Chem. 2013;59(1):280-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(2):120-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll PR, Parsons JK, Andriole G, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Early Detection: Version 2.2017. [published online February 21, 2017, by National Comprehensive Cancer Network Inc]. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2017.

- 20.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2005;293(17):2095-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stokes ME, Ishak J, Proskorovsky I, Black LK, Huang Y. Lifetime economic burden of prostate cancer. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma X, Wang R, Long JB, et al. The cost implications of prostate cancer screening in the Medicare population. Cancer. 2014;120(1):96-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard DH, Bach PB, Berndt ER, Conti R. Pricing in the market for anticancer drugs. J Econ Perspect. 2015;29(1):139-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(8):529-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettersson A, Graff RE, Bauer SR, et al. The TMPRSS2:ERG rearrangement, ERG expression, and prostate cancer outcomes: a cohort study and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(9):1497-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young A, Palanisamy N, Siddiqui J, et al. Correlation of urine TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 to ERG+ and total prostate cancer burden. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138(5):685-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornu JN, Cancel-Tassin G, Egrot C, Gaffory C, Haab F, Cussenot O. Urine TMPRSS2:ERG fusion transcript integrated with PCA3 score, genotyping, and biological features are correlated to the results of prostatic biopsies in men at risk of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2013;73(3):242-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Poppel H, Haese A, Graefen M, et al. The relationship between Prostate CAncer gene 3 (PCA3) and prostate cancer significance. BJU Int. 2012;109(3):360-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auprich M, Chun FK, Ward JF, et al. Critical assessment of preoperative urinary prostate cancer antigen 3 on the accuracy of prostate cancer staging. Eur Urol. 2011;59(1):96-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chevli KK, Duff M, Walter P, et al. Urinary PCA3 as a predictor of prostate cancer in a cohort of 3,073 men undergoing initial prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2014;191(6):1743-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de la Taille A, Irani J, Graefen M, et al. Clinical evaluation of the PCA3 assay in guiding initial biopsy decisions. J Urol. 2011;185(6):2119-2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deras IL, Aubin SM, Blase A, et al. PCA3: a molecular urine assay for predicting prostate biopsy outcome. J Urol. 2008;179(4):1587-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips R. Prostate cancer: Improving early detection—can PCA3 do more? Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12(1):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hessels D, Smit FP, Verhaegh GW, Witjes JA, Cornel EB, Schalken JA. Detection of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts and prostate cancer antigen 3 in urinary sediments may improve diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(17):5103-5108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salami SS, Schmidt F, Laxman B, et al. Combining urinary detection of TMPRSS2:ERG and PCA3 with serum PSA to predict diagnosis of prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(5):566-571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leyten GH, Hessels D, Jannink SA, et al. Prospective multicentre evaluation of PCA3 and TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions as diagnostic and prognostic urinary biomarkers for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(3):534-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siddiqui MM, Rais-Bahrami S, Turkbey B, et al. Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. JAMA. 2015;313(4):390-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Catalona WJ, Partin AW, Sanda MG, et al. A multicenter study of [-2]pro-prostate specific antigen combined with prostate specific antigen and free prostate specific antigen for prostate cancer detection in the 2.0 to 10.0 ng/ml prostate specific antigen range. J Urol. 2011;185(5):1650-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vickers A, Cronin A, Roobol M, et al. Reducing unnecessary biopsy during prostate cancer screening using a four-kallikrein panel: an independent replication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2493-2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parekh DJ, Punnen S, Sjoberg DD, et al. A multi-institutional prospective trial in the USA confirms that the 4Kscore accurately identifies men with high-grade prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68(3):464-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Subject Characteristics in the NCI-EDRN Urinary PC3 Evaluation Trial Validation Cohort

eFigure 1. STARD Study Flow Diagram for Developmental cohort

eFigure 2. STARD Study Flow Diagram for Validation Cohort

eFigure 3. Cost analysis and model assumption details

eAppendix.