Key Points

Question

Do recent immigrant patients experience different end-of-life care than long-standing resident patients?

Findings

In this cohort study that included 967 013 patients, recent immigrant patients were more likely to be in the intensive care unit when they died and were more likely to receive invasive procedures in the last 6 months of life including hospital admission, intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, dialysis, or percutaneous feeding tube placement. These outcomes varied most significantly according to region of origin rather than socioeconomic position, language ability on arrival, or education level on arrival.

Meaning

Among decedents in Ontario, Canada, recent immigrants were significantly more likely to receive aggressive care and to die in an intensive care unit compared with other residents. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms behind this association.

Abstract

Importance

People who immigrate face unique health literacy, communication, and system navigation challenges, and they may have diverse preferences that influence end-of-life care.

Objective

To examine end-of-life care provided to immigrants to Canada in the last 6 months of their life.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study (April 1, 2004, to March 31, 2015) included 967 013 decedents in Ontario, Canada, using validated linkages between health and immigration databases to identify immigrant (since 1985) and long-standing resident cohorts.

Exposures

All decedents who immigrated to Canada between 1985 and 2015 were classified as recent immigrants, with subgroup analyses assessing the association of time since immigration, and region of birth, with end-of-life care.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Location of death and intensity of care received in the last 6 months of life. Analysis included modified Poisson regression with generalized estimating equations, adjusting for age, sex, socioeconomic position, causes of death, urban and rural residence, and preexisting comorbidities.

Results

Among 967 013 decedents of whom 47 514 (5%) immigrated since 1985, sex, socioeconomic status, urban (vs rural) residence, and causes of death were similar, while long-standing residents were older than immigrant decedents (median [interquartile range] age, 75 [58-84] vs 80 [68-87] years). Recent immigrant decedents were overall more likely to die in intensive care (15.6% vs 10.0%; difference, 5.6%; 95% CI, 5.2%-5.9%) after adjusting for differences in age, sex, income, geography, and cause of death (relative risk, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.27-1.32). In their last 6 months of life, recent immigrant decedents experienced more intensive care admissions (24.9% vs 19.2%; difference, 5.7%; 95% CI, 5.3%-6.1%), hospital admissions (72.1% vs 68.2%; difference, 3.9%; 95% CI, 3.5%-4.3%), mechanical ventilation (21.5% vs 13.6%; difference, 7.9%; 95% CI, 7.5%-8.3%), dialysis (5.5% vs 3.4%; difference, 2.1%; 95% CI, 1.9%-2.3%), percutaneous feeding tube placement (5.5% vs 3.0%; difference, 2.5%; 95% CI, 2.3%-2.8%), and tracheostomy (2.3% vs 1.1%; difference, 1.2%; 95% CI, 1.1%-1.4%). Relative risk of dying in intensive care for recent immigrants compared with long-standing residents varied according to recent immigrant region of birth from 0.84 (95% CI, 0.74-0.95) among those born in Northern and Western Europe to 1.96 (95% CI, 1.89-2.05) among those born in South Asia.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among decedents in Ontario, Canada, recent immigrants were significantly more likely to receive aggressive care and to die in an intensive care unit compared with other residents. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms behind this association.

This population-based cohort study characterizes the intensity of care and locations of death of immigrants in the last 6 months of their life in Ontario, Canada.

Introduction

Optimal end-of-life care combines best medical therapy and symptom control in accordance with patient wishes. Many patients receive aggressive in-hospital end-of-life care despite a preference for dying in a familiar setting, free from invasive technology. This discrepancy has many contributors, including inadequate advance care planning, suboptimal communication between health care professionals and patients or their families, poor health literacy, uncertainty about imminence of death, and unavailability of nonintensive end-of-life or palliative care resources.

Canada has high rates of immigration relative to many high-income nations, which in turn leads to a diversity of geographic, cultural, and racial/ethnic backgrounds among its residents. In 2011 (midway through this study), Ontario, Canada, had a population of 12 851 821, of whom 3 611 365 (29%) were born in other countries and 501 060 (4%) arrived in Canada between 2006 and 2011. Immigrants often face challenges in communication, health literacy, and navigation of the health care system. Although immigrants are on average healthier than age-matched Canadians when they arrive in Canada, they subsequently experience excess morbidity and mortality from chronic medical and psychiatric conditions.

Preliminary evidence suggests that some immigrants may face cultural and logistical challenges in end-of-life care due to decreased health literacy or language ability, different modes of family-based decision-making and filial responsibility, and decreased access to care due to insufficient financial and social resources. Some immigrants may have different end-of-life care preferences than many long-standing residents. To our knowledge, there are no comprehensive large-scale quantitative studies of end-of-life care in recent immigrant populations. This population-based analysis was conducted to describe end-of-life care delivered to recently immigrated compared with long-standing resident decedents, including magnitude of and factors associated with differences in end-of-life care.

Methods

Study Setting and Oversight

The study was approved by the research ethics board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre including a waiver for individual patient consent because the data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

Identification of Decedents (Study Participants)

All individuals (recent immigrants and long-standing residents) who died in Ontario between April 1, 2004, and March 31, 2015, were identified. Individuals with fewer than 6 months of enrollment in the provincial health care plan were excluded. Data on individuals who received care in Ontario but died in another country or province were not available. Patients with some missing baseline data were included in unadjusted analyses but not in adjusted analyses requiring a missing variable.

Recent immigrants were identified within the data set through previously validated combined probabilistic and deterministic linkage of the list of deceased individuals to the registry of landed immigrants maintained by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Deterministic linkage occurs when 1 or more identifiers (eg, health card number and name) are identical, while probabilistic linkage uses probability scores to identify linkages among records where deterministic linkages were not possible. Recent immigrants were defined as those granted permanent residency or citizenship status in Canada between 1985 and 2015 (the years available in the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada data) and created subgroups according to duration since immigration. All other residents were defined as long-standing residents. Other research has reserved the term recent for immigrants arriving within shorter timeframes, but this broader definition sought to include all available data and acknowledge that some members of the long-standing resident cohort may also be immigrants but have lived in Canada for more than 30 years. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada data also included information obtained at the time of immigration application on immigration class (economic, family, refugee, and other), education level, language ability, and country of birth. Information on the level of health literacy, religion, and specific cultural practices was not available.

Identification of Health Care Use Prior to Death

A combination of health administrative databases linked at the individual level were used to describe health care service use at the population level in Ontario. These included the Registered Persons Database containing vital statistics on all persons issued a Provincial Health Card, the Ontario Health Insurance Plan containing data on all professional services and procedures resulting in charges to the health care system, the Office of the Registrar General for Deaths, the Discharge Abstract Database containing detailed patient-level information including resources used and procedures performed for all inpatients, and the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System for similar data among ambulatory hospital admissions and emergency department presentations. Although these databases do not include care provided at community health centers (frequented by some recent immigrants, but overall reaching less than 1% of the population), the databases contain comprehensive coverage of care provided in hospitals.

Characteristics of Patients

Patient characteristics and demographics are reported including age, sex, socioeconomic position based on postal code census data, and place of residence at time of death. Data are reported on intensive care admissions, chronic conditions including the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Deyo modification), hospitalizations, procedures, and emergency department visits during the final 24 months of life, with emphasis on the final 6 months. The database does not contain specific information on do-not-resuscitate orders, advanced care planning, or overall goals of care but captures the consequences of these decisions with respect to health care delivery.

Outcomes

The primary outcome described end-of-life care according to location of death: intensive care unit, acute care hospital, long-term care facility (or nursing home), and other (including hospice or home). The results are described in terms of relative risk (RR), which in this case refers to the ratio of proportions of recent immigrant compared with long-standing resident decedents that experienced a given outcome. Secondary outcomes assessed whether a patient experienced intensive or invasive interventions in the last 6 months of life including hospital admission, intensive care admission, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, percutaneous gastric/gastrojejunal tube, or tracheostomy. Other secondary outcomes included emergency department, hospital, and intensive care use in the last 6 months of life.

Subgroup Analyses

Prespecified subgroup analyses were performed according to patient demographics (age, sex, urban or rural place of residence, and socioeconomic position), comorbidity (specific diagnostic categories and Charlson Comorbidity Index), and recent immigrant characteristics (immigration class, language ability on arrival, education level on arrival, time since immigration, and region of birth) (eTable 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Recent immigrant and long-standing resident end-of-life care was compared using χ2 testing for categorical outcomes (location of death and proportion receiving invasive interventions) and rates (emergency department presentation, hospital admission, and intensive care admission), Mann-Whitney tests for comparisons of median duration of stay (hospital and intensive care admissions) and number of episodes (hospital and intensive care admissions and emergency department visits), and t tests for comparisons of mean duration (hospital and intensive care unit admissions).

Separate modified Poisson regression analyses of location of death (intensive care unit, acute care hospital, long-term care facility, or other including home) were conducted among recent immigrants compared with long-standing resident decedents to estimate RRs. We also performed separate modified Poisson regression analyses of type of invasive care received in the last 6 months including hospital admission, intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, percutaneous feeding tube placement, and tracheostomy. All analyses adjusted for potential confounders of age, sex, income quintile, urban-rural residence, and cause of death. To account for the correlation of outcomes among patients residing within the same geographic area, the analysis implemented generalized estimating equations using an exchangeable correlation structure, clustering by postal code. Recent immigrants were separately analyzed according to region of birth, years in Ontario, language ability on arrival, education level on arrival, and immigration class while adjusting for the same covariates as above. Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered significant but were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Analyses were performed with SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 (SAS Institute) and R 3.2.2 software (R Foundation). Details of the analysis protocol, regional definitions, causes of death, and further analyses assessing robustness across multiple fixed intervals preceding death can be found in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 967 013 decedents were analyzed, of whom 47 514 (5%) immigrated since 1985. Recent immigrant decedents originated from diverse global regions (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The median age at death was 79 years, with ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, and dementia being the most common causes of death. Compared with long-standing resident decedents, recent immigrant decedents tended to be younger and more likely to live in an urban area and of lower socioeconomic position (Table 1). The median duration in Canada for recent immigrants was 16 years.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Deceased Patients (N = 967 013)a.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Standardized Difference of Means | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-standing Residents (n = 919 499) |

Recent Immigrants (n = 47 514) |

||

| Age at death, y | |||

| Median (IQR) | 80 (68-87) | 75 (58-84) | 0.33 |

| ≤40 | 25 731 (3) | 3250 (7) | 0.19 |

| 41-60 | 109 851 (12) | 10 169 (21) | 0.26 |

| 61-80 | 346 016 (38) | 17 267 (36) | 0.03 |

| ≥81 | 437 901 (48) | 16 828 (35) | 0.25 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 461 318 (50) | 23 217 (49) | 0.03 |

| Male | 458 181 (50) | 24 297 (51) | 0.03 |

| Income quintileb | |||

| First (lowest) | 212 052 (23) | 14 373 (30) | 0.16 |

| Second | 191 583 (21) | 10 878 (23) | 0.05 |

| Third | 174 606 (19) | 9029 (19) | <0.01 |

| Fourth | 170 366 (19) | 7692 (16) | 0.06 |

| Fifth (highest) | 165 708 (18) | 5435 (12) | 0.19 |

| Metropolitan influence zonec | |||

| None (least urban) | 116 641 (13) | 742 (2) | 0.44 |

| Weak | 290 846 (32) | 5148 (11) | 0.53 |

| Moderate | 179 758 (20) | 4151 (9) | 0.31 |

| Strong (most urban) | 332 142 (36) | 37 462 (79) | 0.96 |

| Cause of deathd | |||

| Ischemic heart disease | 124 796 (14) | 5089 (11) | 0.09 |

| Cancer of lung and bronchus | 58 043 (6) | 2314 (5) | 0.06 |

| Dementia and Alzheimer disease | 53 053 (6) | 1628 (3) | 0.11 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 47 599 (5) | 2596 (6) | 0.01 |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 31 778 (4) | 730 (2) | 0.12 |

| Cancer of colon, rectum, or anus | 27 878 (3) | 1323 (3) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 24 516 (3) | 1245 (3) | <0.01 |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 22 737 (3) | 1061 (2) | 0.02 |

| Cancer of lymph, blood and related | 21 853 (2) | 1333 (3) | 0.03 |

| Cancer of breast | 16 886 (2) | 1171 (3) | 0.04 |

| Others | 490 360 (53) | 29 024 (61) | 0.16 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | |||

| ≤2 | 383 790 (42) | 17 773 (37) | 0.1 |

| 3-4 | 170 153 (19) | 8623 (18) | 0.01 |

| ≥5 | 270 605 (29) | 16 477 (35) | 0.12 |

| Missinge | 94 951 (10) | 4641 (10) | |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

This Table shows the baseline characteristics for each cohort in absolute number and percentage form. As a consequence of large sample sizes, all differences are significant by χ2 testing. The standardized difference of means is included as a more appropriate test of difference between subgroups with large sample sizes. Standardized differences show the ratio of the difference in means and SDs. Values less than 0.1 are generally considered to reflect negligible differences between subgroups.

Defined by postal code average income.

Describes the extent to which an area is urbanized, with “strong” being the most urbanized.

Selected from most common; additional information available in eTable 11 in the Supplement, which includes 67 categories of causes of death ordered by prevalence.

No admissions in final 24 months of life.

End-of-Life Care

Of the 967 013 decedents, 434 783 (45%) died in the hospital including 99 680 (10%) who died in intensive care. Compared with long-standing resident decedents, a higher proportion of recent immigrant decedents died in intensive care (15.6% vs 10.0%; difference, 5.6%; 95% CI, 5.2%-5.9%) (Table 2). This increase persisted after adjusting for differences in age, sex, income, geography, and cause of death (Table 3) (adjusted RR of dying in intensive care comparing recent immigrant with long-standing resident decedents: 1.30; 95% CI, 1.27-1.32; Table 2).

Table 2. Location of Death and Care Received in the Final 6 Months of Lifea.

| Variable | Long-standing Residents (n = 919 499) |

Recent Immigrants (n = 47 514) |

Absolute Difference in Percentage Points (95% CI) | Unadjusted Relative Risk (95% CI) | Adjusted Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of death, No. (%) | |||||

| ICU | 92 270 (10) | 7410 (16) | 5.6 (5.2 to 5.9) | 1.55 (1.52 to 1.59) | 1.30 (1.27 to 1.32) |

| Acute care hospital (not ICU) | 317 830 (35) | 17 273 (36) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.2) | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.06) | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.09) |

| Long-term care facility | 73 628 (8) | 3608 (8) | –0.4 (–0.2 to –0.6) | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.98) | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.95) |

| Other (including home) | 435 771 (47) | 19 223 (41) | –6.9 (–6.5 to –7.4) | 0.85 (0.84 to 0.86) | 0.89 (0.88 to 0.90) |

| Care received in final 6 mo, No. (%) | |||||

| Hospital admission | 626 739 (68) | 34 261 (72) | 3.9 (3.5 to 4.3) | 1.06 (1.05 to 1.06) | 1.04 (1.04 to 1.06) |

| ICU admission | 176 417 (19) | 11 840 (25) | 5.7 (5.3 to 6.1) | 1.30 (1.28 to 1.32) | 1.16 (1.15 to 1.19) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 125 246 (14) | 10 227 (22) | 7.9 (7.5 to 8.3) | 1.60 (1.54 to 1.66) | 1.28 (1.25 to 1.30) |

| Dialysis | 31 639 (3) | 2615 (6) | 2.1 (1.9 to 2.3) | 1.58 (1.55 to 1.61) | 1.39 (1.33 to 1.45) |

| Percutaneous feeding tube | 27 438 (3) | 2627 (6) | 2.5 (2.3 to 2.8) | 1.85 (1.78 to 1.93) | 1.51 (1.45 to 1.59) |

| Tracheostomy | 9978 (1) | 1091 (2) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | 2.12 (1.99 to 2.25) | 1.61 (1.51 to 1.72) |

| Care episodes in final 6 mo, median (IQR)b | |||||

| Hospital admission length, dc | 6 (0-19) | 7 (0-22) | |||

| Hospital admissions, No.c | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | |||

| ICU admission length, dc | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | |||

| ICU admissions, No.c | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | |||

| Emergency department visits, No.d | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Each relative risk calculated in binary fashion, eg, death in ICU compared with death in all other locations. Exposure variables in modified Poisson regression analyses: age, sex, income quintile, urbanization of place of living, date of death, and cause of death (categories: cancer, cardiovascular, sepsis, and other). This table shows the outcome data in absolute and percentage form, with unadjusted relative risk and adjusted relative risk based on modified Poisson regression showing the magnitude and significance of any differences. Positive absolute percentage differences indicate increased percentage of recent immigrants as compared with long-standing residents.

Care episode data show the median and interquartile range for the number of emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and ICU admissions per decedent, as well as the median and interquartile range of the duration of hospital and ICU admission per decedent.

Between-group comparison, P < .001.

Between-group comparison, P = .15.

Table 3. Modified Poisson Regression for Relative Risk of Each Location of Death (N = 967 013)a.

| Variable | Intensive Care (n = 99 680) |

Hospital (Non-ICU) (n = 335 103) |

Long-term Care (77 236) |

Other (454 994) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Decedents (%) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | No. of Decedents (%) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | No. of Decedents (%) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | No. of Decedents (%) | Adjusted RR (95%) | |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| ≤40 | 4977 (5) | 1 [Reference] | 4049 (1) | 1 [Reference] | 584 (1) | 1 [Reference] | 19 371 (4) | 1 [Reference] |

| 41-60 | 18 487 (19) | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) | 33 995 (10) | 1.95 (1.90-2.02) | 7789 (10) | 2.69 (2.48-2.93) | 59 749 (13) | 0.76 (0.75-0.77) |

| 61-80 | 49 283 (49) | 0.90 (0.87-0.92) | 135 734 (41) | 2.61 (2.54-2.69) | 32 532 (42) | 3.83 (3.53-4.16) | 145 734 (32) | 0.60 (0.60-0.61) |

| ≥81 | 26 933 (27) | 0.34 (0.33-0.35) | 161 325 (48) | 2.67 (2.59-2.76) | 36 331 (47) | 4.22 (3.87-4.60) | 230 140 (51) | 0.72 (0.71-0.73) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 56 243 (56) | 1 [Reference] | 165 059 (49) | 1 [Reference] | 39 039 (51) | 1 [Reference] | 237 000 (52) | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 43 437 (44) | 1.10 (1.08-1.11) | 170 044 (51) | 1.06 (1.05-1.06) | 38 197 (49) | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | 217 994 (48) | 0.93 (0.93-0.94) |

| Income quintile | ||||||||

| First (lowest) | 24 250 (24) | 1 [Reference] | 78 807 (24) | 1 [Reference] | 17 997 (23) | 1 [Reference] | 105 371 (23) | 1 [Reference] |

| Second | 21 722 (22) | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) | 72 911 (22) | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | 17 019 (22) | 1.02 (0.95-1.08) | 90 809 (20) | 0.98 (0.95-1.00) |

| Third | 18 723 (19) | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 64 277 (19) | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | 14 481 (19) | 0.95 (0.90-1.00) | 86 154 (19) | 1.02 (0.99-1.04) |

| Fourth | 17 820 (18) | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | 60 914 (18) | 0.96 (0.94-0.99) | 13 858 (18) | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) | 85 466 (19) | 1.04 (1.02-1.07) |

| Fifth (highest) | 16 647 (17) | 1.00 (0.96-1.03) | 56 619 (17) | 0.93 (0.90-0.95) | 13 391 (17) | 0.92 (0.87-0.97) | 84 486 (19) | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) |

| Metropolitan influence zoneb | ||||||||

| None (least urban) | 10 222 (10) | 1 [Reference] | 42 582 (13) | 1 [Reference] | 7550 (10) | 1 [Reference] | 57 029 (13) | 1 [Reference] |

| Weak | 28 675 (29) | 1.11 (1.06-1.16) | 99 393 (30) | 0.92 (0.90-0.95) | 26 521 (34) | 1.39 (1.31-1.48) | 141 405 (31) | 0.99 (0.95-1.02) |

| Moderate | 17 967 (18) | 1.13 (1.08-1.19) | 58 512 (17) | 0.87 (0.84-0.90) | 10 256 (13) | 0.86 (0.79-0.92) | 97 174 (21) | 1.10 (1.06-1.13) |

| Strong (most urban) | 42 806 (43) | 1.30 (1.25-1.35) | 134 580 (40) | 0.99 (0.97-0.78) | 32 901 (43) | 1.38 (1.30-1.46) | 159 317 (35) | 0.90 (0.88-0.93) |

| Cause of deathc | ||||||||

| Other | 52 341 (53) | 1 [Reference] | 149 791 (45) | 1 [Reference] | 31 053 (40) | 1 [Reference] | 228 138 (50) | 1 [Reference] |

| Cancer | 10 833 (11) | 0.36 (0.35-0.37) | 97 956 (29) | 1.32 (1.30-1.33) | 33 481 (43) | 2.31 (2.26-2.36) | 81 148 (18) | 0.77 (0.77-0.78) |

| Cardiovascular | 28 453 (29) | 1.13 (1.11-1.14) | 68 602 (20) | 0.82 (0.81-0.83) | 11 109 (14) | 0.66 (0.65-0.68) | 134 205 (29) | 1.15 (1.14-1.16) |

| Sepsis | 8053 (8) | 2.06 (2.02-2.10) | 18 754 (6) | 1.38 (1.36-1.39) | 1593 (2) | 0.56 (0.53-0.59) | 11 503 (3) | 0.59 (0.58-0.60) |

| Date of death (per year between 2004 and 2015) | 1.001 (0.999-1.003) |

0.988 (0.988-0.989) |

1.01 (1.01-1.02) | 1.001 (1.006-1.007) |

||||

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; RR, relative risk.

This Table shows the adjusted relative risks of dying in intensive care associated with each row variable estimated by modified Poisson regression with generalized estimating equations incorporating postal code geographic data as well as immigration status (see Table 2) and each variable in the rows of the table.

Describes the extent to which an area is urbanized, with “strong” being the most urbanized.

Diagnostic categories defined in eTable 11 in the Supplement, according to clinically relevant subsets of causes of death.

In their last 6 months of life, recent immigrant decedents experienced more intensive care admissions (24.9% vs 19.2%; difference, 5.7%; 95% CI, 5.3%-6.1%), hospital admissions (72.1% vs 68.2%; difference, 3.9%; 95% CI, 3.5%-4.3%), mechanical ventilation (21.5% vs 13.6%; difference, 7.9%; 95% CI, 7.5%-8.3%), dialysis (5.5% vs 3.4%; difference, 2.1%; 95% CI, 1.9%-2.3%), percutaneous feeding tube placement (5.5% vs 3.0%; difference, 2.5%; 95% CI, 2.3%-2.8%), and tracheostomy (2.3% vs 1.1%; difference, 1.2%; 95% CI, 1.1%-1.4%) , even after adjusting for potential confounders (Table 2 and eTable 4 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). These increases persisted across various fixed intervals preceding death (1 month, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Subgroup Analyses

Our finding that recent immigrant decedents were more likely to die in intensive care was consistent across diverse subgroups including older age at death, sex, socioeconomic status, place of residence, and Charlson Comorbidity Index score (Figure 1). The association persisted across different conditions including colorectal cancer (RR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.02-1.57), diabetes (RR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.74-2.28), cerebrovascular disease (RR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.98-2.28), and dementia (RR, 3.69; 95% CI, 2.66-5.13).

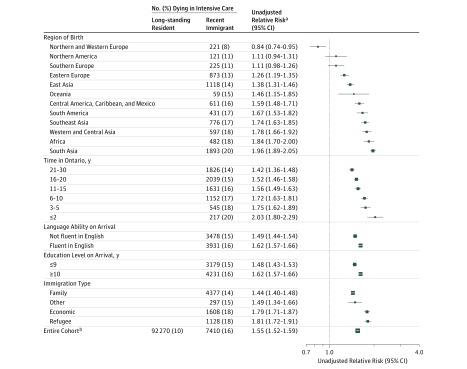

Figure 1. Proportion of Decedents Dying in Intensive Carea.

Forest plot depicting the ratio of the proportions of decedents dying in intensive care units comparing recent immigrant with long-standing resident cohorts (relative risk). Relative risks greater than 1 correspond to an increased relative risk of recent immigrant compared with long-standing resident decedents being in the intensive care unit at death. The size of each square is proportional to the precision of the relative risk estimate.

aThe denominator for each row is the total number of decedents in each cohort in each subgroup by row, ie, the denominator for each cell in the corresponding cell in Table 1.

bDenotes the extent to which an area is urbanized, with “strong” being the most urbanized.

The RR of death in intensive care comparing recent immigrant and long-standing resident decedents was highest among patients older than 80 years, female patients, and patients with a lower comorbidity index (Figure 1). There was substantial variation in end-of-life care according to region of birth and time since immigration (Figure 2). The RR of dying in intensive care (using the overall long-standing resident risk of dying in intensive care as baseline) ranged from 0.84 (95% CI, 0.74-0.95) among decedents born in northern and western Europe to 1.78 (95% CI, 1.66-1.92) among decedents born in western and central Asia, 1.84 (95% CI, 1.70-2.00) among decedents born in Africa, and 1.96 (95% CI, 1.89-2.05) among decedents born in South Asia (eFigure 2 in Supplement). After adjustment for age and other covariates in the recent immigrant population, the increased RR of dying in intensive care persisted among recent immigrant decedents from East Asia, Central America and Mexico, South America, Africa, western and central Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. All other regions, including Northern and Western Europe, did not show statistically significant differences from Northern America (eTable 6 in Supplement). Differences were associated with time in Canada, with an RR of dying in intensive care of 1.42 (95% CI, 1.36-1.48) among those who immigrated 21 to 30 years before death and an RR of 2.03 (95% CI, 1.80-2.29) seen in those who immigrated fewer than 2 years before death. In adjusted analyses, the increased RR of dying in intensive care seen among recent immigrant decedents who immigrated 2 or fewer years before death remained statistically significant relative to recent immigrant decedents who immigrated more than 10 years before death, but the differences between those who immigrated 2 or fewer years before death and those who immigrated between 3 and 10 years before death were no longer statistically significant (eTable 6 in the Supplement). There were no significant differences in the adjusted analysis according to immigration class, language ability on arrival, socioeconomic position, or education level on arrival.

Figure 2. Proportion of Decedents Dying in Intensive Care: Recent Immigrant Characteristicsa.

Forest plot analogous to Figure 1 depicting the ratio of the proportions of decedents dying in intensive care units comparing recent immigrant with long-standing resident cohorts (relative risk). In contrast to Figure 1, this figure focuses on subgroups defined only among the recent immigrant cohort including region of origin, language ability on arrival, education level on arrival, immigration class, and time since immigration. The proportion of recent immigrant decedents dying in intensive care within each subgroup is compared with the proportion of long-standing resident decedents dying in intensive care (92 270 of 919 499 [10%]), and so a relative risk greater than 1 corresponds to an increased relative risk of recent immigrant compared with long-standing resident decedents being in the intensive care unit at death. Note that percentages are based on the size of each subgroup by row, not based on the overall analytic sample size for recent immigrant decedents of 47 514. The size of each square is proportional to the precision of the relative risk estimate.

aThe denominator data for the percentages are the total numbers of recent immigrant decedents in each subgroup, ie, the corresponding cells in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Sensitivity Analyses

The primary analysis does not include recent immigrant decedents who left Ontario before death. However, for the 95% CI of our estimate for proportion of recent immigrant decedents dying in intensive care to overlap with the corresponding quantity among long-standing residents, 26 329 recent immigrants (36%) would have had to leave Ontario and then die outside of an intensive care unit (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement).

A total of 14 758 decedents were excluded owing to fewer than 6 months of health care enrollment, of whom 458 (3%) were recent immigrants. The prevalence of missing data was highest in the Charlson Comorbidity Index score data because of a subset of patients who were never hospitalized, but otherwise the proportion of missing data was small (eTable 7 in Supplement).

Other sensitivity analyses assessed the difference between recent immigrants identified through deterministic as opposed to probabilistic matching. Of the 47 514 recent immigrant decedents identified, 37 046 (78%) were identified with deterministic linking and 10 468 (22%) were identified with probabilistic linking (eTable 8 in the Supplement). The 2 cohorts of recent immigrants were similar with respect to baseline characteristics, unadjusted primary analysis, and adjusted secondary analyses (eTables 3, 9, 10, and 11 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Among decedents in Ontario, recent immigrants were significantly more likely to receive aggressive care and to die in an intensive care unit than long-standing residents. In the last 6 months of life, recent immigrant decedents were more likely to experience intensive care unit admission, hospital admission, mechanical ventilation, dialysis, percutaneous feeding tube placement, and tracheostomy. These increased rates of aggressive care varied substantially according to region of birth, attenuated with time in Canada, and were not explained by differences in age, sex, cause of death, comorbidity, or socioeconomic position.

This study is a large-scale population-level quantitative analysis of end-of-life care provided to patients who have recently immigrated, using comprehensive data on hospital care as a consequence of universal health insurance. The data show extensive global region variation, with recent immigrants from Northern and Western Europe experiencing less-aggressive end-of-life care than long-standing residents, while those from Africa, South Asia, or Southeast Asia experienced the most-aggressive end-of-life care relative to long-standing residents. Qualitative research conducted in multiple cultural settings corroborates the finding that differences in end-of-life care provided to recent immigrants may be associated with region of origin. Within Europe and Asia, variations in the rate of organ-supporting care at the end of life are significantly associated with both region and the culture or religion of patients and physicians. The results agree with quantitative research conducted in racial/ethnic minority groups in the United States. The differences in end-of-life care delivery may also attenuate with time since immigration, consistent with other research describing acculturation and end-of-life care.

The variation in end-of-life care based on region of birth has multiple potential explanations, including patient preferences, cultural differences, clinician behavior, end-of-life care decision processes, or differences in service accessibility. If recent immigrants live in social and geographic communities relating to their region of birth, this could lead to differential palliative care service availability for certain groups. Clinicians may conduct end-of-life care discussions in different ways, or less commonly, based on conscious or subconscious cultural, geographic, or religious perceptions of end-of-life care practices. Variation seen across diagnostic categories suggests the possibility of residual confounding due to clustering of disease processes and immigration status, although the associations with more-aggressive care persist after adjustment for category of cause of death. Many recent immigrant patients and families may be more familiar with clinician-directed or family and community–based models of medical decision-making, leading to different outcomes in an environment where patient preferences or shared patient-clinician decision-making guide end-of-life care decisions. The findings in this study might also be explained by differences in health literacy or language ability that could promote more aggressive end-of-life care through delayed clinical presentations, incomplete understanding of medical situations, or even decreased trust of health care professionals. However, the findings did not appear to be explained by English proficiency, level of education, socioeconomic position, nor place of residence at time of death.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The most important limitation is that the recent immigrant and long-standing resident cohorts differed significantly in terms of age, socioeconomic status, and geography, which leaves the possibility of residual confounding. However, comprehensive coverage of all hospital care for every Canadian resident reduces confounding due to economic barriers that may exist to a greater extent in some other jurisdictions and with adjustment of these and other baseline characteristics, the potential for residual confounding should be greatly reduced. Another limitation is that different diseases have different terminal time courses, while the design analyzed fixed intervals preceding death; therefore, some aspects of end-of-life care may have been missed or some care prior to end of life may have been included. Health administrative databases are also limited in terms of risk adjustment by disease severity; however, decedent analyses involve inherent severity adjustment through selection of patients who have died. Although data were captured on all decedents in Ontario, no data were available about recent immigrants who returned to their country of origin to die; however, these populations are likely very small (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). There were no analyses of hospital length of stay prior to intensive care unit admission. There were no data on or analyses of marital status, language ability for long-standing residents (or language ability more recently than arrival for recent immigrants), education level for long-standing residents, or goals of care and preferences for any patients or families.

Conclusions

Among decedents in Ontario, recent immigrants were significantly more likely to receive aggressive care and to die in an intensive care unit compared with other residents. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms behind this association.

eAppendix 1. eMethods.

eAppendix 2. Sensitivity Analysis of Recent Immigrant Decedents Who Leave Ontario Before Death.

eTable 1. Variables Included in the Analysis.

eTable 2. Immigration, Refugees. and Citizenship Canada Data and Variables.

eTable 3. Baseline Recent Immigrant Characteristics.

eTable 4. Modified Poisson Regression – Care Provided During Final 6 Months of Life.

eTable 5. Multinomial Logistic Regression by Location of Death.

eTable 6. Modified Poisson Regression – Recent Immigrant Location of Death.

eTable 7. Missing Data.

eTable 8. Location of Death and Care Received in the Final Six Months of Life Comparing Deterministic and Probabilistic Matching.

eTable 9. Baseline Characteristics of Deceased Recent Immigrant Patients (N=47,514) by Matching Type.

eTable 10. Trajectories to Intensive Care.

eTable 11. Causes of Death.

eFigure 1. Care Received During Final 1, 6, 12, and 24 Months of Life.

eFigure 2. Relative Risk of Dying in Intensive Care by Region of Origin.

Section Editor: Derek C. Angus, MD, MPH, Associate Editor, JAMA (angusdc@upmc.edu).

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO definition of palliative care. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 2.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. ; Canadian Researchers End-of-Life Network(CARENET) . What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006;174(5):627-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, et al. ; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network (CARENET) . Defining priorities for improving end-of-life care in Canada. CMAJ. 2010;182(16):E747-E752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, Fowler RA. Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(5):1174-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Central Intelligence Agency The World Factbook: country comparison: net migration rate. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2112rank.html. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 6.Statistics Canada Population and dwelling count highlight tables, 2011 census. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table-Tableau.cfm?LANG=Eng&T=101&S=50&O=A. Published January 7, 2016. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 7.Fuller-Thomson E, Noack AM, George U. Health decline among recent immigrants to Canada: findings from a nationally-representative longitudinal survey. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(4):273-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanmartin C, Ross N. Experiencing difficulties accessing first-contact health services in Canada: Canadians without regular doctors and recent immigrants have difficulties accessing first-contact healthcare services: reports of difficulties in accessing care vary by age, sex and region. Healthc Policy. 2006;1(2):103-119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tu JV, Chu A, Rezai MR, et al. The Incidence of Major Cardiovascular Events in Immigrants to Ontario, Canada: the CANHEART Immigrant Study [published online August 31, 2015]. Circulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lackan NA, Eschbach K, Stimpson JP, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Ethnic differences in hospital place of death among older adults in California. Med Care. 2009;47:138-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosma H, Apland L, Kazanjian A. Cultural conceptualizations of hospice palliative care: more similarities than differences. Palliat Med. 2010;24(5):510-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Johnson KS, Curtis LH, Setoguchi S. Racial differences in hospice use and patterns of care after enrollment in hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2012;163(6):987-993.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz-Oliver DM, Talamantes M, Sanchez-Reilly S. What evidence is available on end-of-life (EOL) care and Latino elders? a literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(1):87-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanchate A, Kronman AC, Young-Xu Y, Ash AS, Emanuel E. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life costs: why do minorities cost more than whites? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):493-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AK, Sudore RL, Pérez-Stable EJ. Palliative care for Latino patients and their families: whenever we prayed, she wept. JAMA. 2009;301(10):1047-1057, E1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu M, Lebenbaum M, Lam K, et al. Describing the linkages of the immigration, refugees and citizenship Canada permanent resident data and vital statistics death registry to Ontario’s administrative health database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: A Validation Study. Toronto, ON, Canada: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization ICD-10 version: 2016. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en. Accessed March 21, 2016.

- 19.Glazier RH, Zagorski BM, Rayner J. Comparison of Primary Care Models in Ontario by Demographics, Case Mix and Emergency Department Use, 2008/09 to 2009/10. Toronto, ON, Canada: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2012: 41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yelland LN, Salter AB, Ryan P. Performance of the modified Poisson regression approach for estimating relative risks from clustered prospective data. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(8):984-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adames HY, Chavez-Dueñas NY, Fuentes MA, Salas SP, Perez-Chavez JG. Integration of Latino/a cultural values into palliative health care: a culture centered model. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(2):149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebrahim S, Bance S, Bowman KW. Sikh perspectives towards death and end-of-life care. J Palliat Care. 2011;27(2):170-174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobbs D, Park NS, Jang Y, Meng H. Awareness and completion of advance directives in older Korean-American adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):565-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrido MM, Harrington ST, Prigerson HG. End-of-life treatment preferences: a key to reducing ethnic/racial disparities in advance care planning? Cancer. 2014;120(24):3981-3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higginson IJ, Gomes B, Calanzani N, et al. ; Project PRISMA . Priorities for treatment, care and information if faced with serious illness: a comparative population-based survey in seven European countries. Palliat Med. 2014;28(2):101-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, et al. ; Ethicus Study Group . End-of-life practices in European intensive care units: the Ethicus Study. JAMA. 2003;290(6):790-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, et al. ; ACME Study Investigators and the Asian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group . Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in intensive care units in Asia. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):363-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moss KO, Williams IC. End-of-life preferences in Afro-Caribbean older adults: a systematic literature review. Omega (Westport). 2014;69(3):271-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma RK, Khosla N, Tulsky JA, Carrese JA. Traditional expectations versus US realities: first- and second-generation Asian Indian perspectives on end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(3):311-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright AA, Stieglitz H, Kupersztoch YM, et al. United states acculturation and cancer patients’ end-of-life care. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonnalagadda S, Lin JJ, Nelson JE, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in beliefs about lung cancer care. Chest. 2012;142(5):1251-1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1533-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, et al. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):754-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White DB, Ernecoff N, Buddadhumaruk P, et al. Prevalence of and factors related to discordance about prognosis between physicians and surrogate decision makers of critically ill patients. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2086-2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS. Geographic variation in health care and the problem of measuring racial disparities. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48(1)(suppl):S42-S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bach PB, Schrag D, Begg CB. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: a study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA. 2004;292(22):2765-2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. eMethods.

eAppendix 2. Sensitivity Analysis of Recent Immigrant Decedents Who Leave Ontario Before Death.

eTable 1. Variables Included in the Analysis.

eTable 2. Immigration, Refugees. and Citizenship Canada Data and Variables.

eTable 3. Baseline Recent Immigrant Characteristics.

eTable 4. Modified Poisson Regression – Care Provided During Final 6 Months of Life.

eTable 5. Multinomial Logistic Regression by Location of Death.

eTable 6. Modified Poisson Regression – Recent Immigrant Location of Death.

eTable 7. Missing Data.

eTable 8. Location of Death and Care Received in the Final Six Months of Life Comparing Deterministic and Probabilistic Matching.

eTable 9. Baseline Characteristics of Deceased Recent Immigrant Patients (N=47,514) by Matching Type.

eTable 10. Trajectories to Intensive Care.

eTable 11. Causes of Death.

eFigure 1. Care Received During Final 1, 6, 12, and 24 Months of Life.

eFigure 2. Relative Risk of Dying in Intensive Care by Region of Origin.