Key Points

Question

Is human immunodeficiency virus preexposure prophylaxis safe and feasible to use for adolescent men who sex with men?

Findings

In this study, preexposure prophylaxis was found to be safe and well-tolerated, but adherence to the daily pill waned. Rates of sexually transmitted infections were high and human immunodeficiency virus infections occurred among those with poor adherence.

Meaning

Adolescent men who have sex with men who are at risk of contracting the human immunodeficiency virus should be offered access to preexposure prophylaxis with appropriate behavioral support to maintain adherence.

Abstract

Importance

Adolescents represent a key population for implementing preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) interventions worldwide, yet tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) for PrEP is only licensed for adults.

Objective

To examine the safety of and adherence to PrEP along with changes in sexual risk behavior among adolescent men who have sex with men (MSM).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions 113 (Project PrEPare) was a PrEP demonstration project that evaluated the safety, tolerability, and acceptability of TDF/FTC and patterns of use, rates of adherence, and patterns of sexual risk behavior among healthy young MSM aged 15 to 17 years. Participants were recruited from adolescent medicine clinics and their community partners in 6 US cities, had negative test results for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) but were at high risk for acquiring an infection, and were willing to participate in a behavioral intervention and accept TDF/FTC as PrEP.

Exposures

All participants completed an individualized evidence-based behavioral intervention and were provided with daily TDF/FTC as PrEP for 48 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main objectives were to: (1) provide additional safety data regarding TDF/FTC use among young MSM who had negative test results for HIV; (2) examine the acceptability, patterns of use, rates of adherence, and measured levels of tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots; and (3) examine patterns of risk behavior when young MSM were provided with a behavioral intervention in conjunction with open-label TDF/FTC.

Results

Among 2864 individuals screened (from August 2013 to September 2014), 260 were eligible and 78 were enrolled (mean [SD] age, 16.5 [0.73] years), of whom 2 (3%) were Asian/Pacific Islander, 23 (29%) were black/African American, 11 (14%) were white, 16 (21%) were white Hispanic, and 26 (33%) were other/mixed race/ethnicity. Over 48 weeks of PrEP use, 23 sexually transmitted infections were diagnosed in 12 participants. The HIV seroconversion rate was 6.4 (95% CI: 1.3-18.7) per 100 person-years. Tenofovir diphosphate levels consistent with a high degree of anti-HIV protection (>700 fmol/punch) were found in 42 (54%), 37 (47%), 38 (49%), 22 (28%), 13 (17%), and 17 (22%) participants at weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48, respectively.

Conclusions and Relevance

Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions 113 enrolled a diverse sample of adolescent MSM at risk for HIV who consented to study participation. Approximately half achieved protective drug levels during the monthly visits, but adherence decreased with quarterly visits. Youth may need additional contact with clinical staff members to maintain high adherence.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01769456

The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions 113 clinical trial examines the safety of administering preexposure prophylaxis to adolescent men who sex with men.

Introduction

In July 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) based on 3 studies that demonstrated efficacy for preventing HIV. Since then, several open-label clinical trials and demonstration projects have supported the effectiveness of administering daily oral PrEP to prevent HIV. None of these clinical trials included adolescent participants younger than 18 years, precluding regulatory agencies from considering the approval of TDF/FTC use for minors. Thus, a critical gap in approved prevention products exists for adolescents, a population that is highly vulnerable to HIV worldwide.

According to the World Health Organization, AIDS is the leading cause of death among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa and the second leading cause for adolescents worldwide. In 2015, there were an estimated 1.8 million adolescents aged 10 to 19 years who were living with HIV, and an adolescent aged 10 to 19 years was infected with HIV every 2 minutes. In the United States, adolescents and young adults aged 13 to 24 years made up 22% of all new infections in 2014, and 80% of those infections were among young men who have sex with men (YMSM).

To expand regulatory approvals and inform PrEP implementation efforts for young people, we designed Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions113 (ATN 113) as an open-label demonstration project and phase 2 safety study for adolescent MSM age 15 to 17 years in the United States.

Methods

Study Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited in person and online through clinical sites that were affiliated with ATN. Eligible participants were aged 15 to 17 years, born male, and had negative test results for HIV as determined by a blood-based antibody assay and an HIV RNA assay at the screening visit. An additional requirement, based on similar criteria from the Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative open-label trial, was self-reported risk for HIV acquisition via any of the following in the last 6 months: condomless anal intercourse with a male partner with an HIV infection or unknown HIV status, anal intercourse with at least 3 male partners, exchange sex, or sexually transmitted infection (STI). We excluded participants who had an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 75 mL/min using the bedside calculation by Schwartz and colleagues, and we also excluded those with a reactive hepatitis B surface antigen, a history of bone fractures, confirmed baseline hypophosphatemia, proteinuria or glycosuria, and liver function and hematology abnormalities that were grade 3 or more.

Eligible participants received 1 individual behavioral risk reduction session using Personalized Cognitive Counseling before the PrEP medication initiation. Study visits were conducted at baseline and monthly for 3 months, then quarterly through week 48. Participants received a comprehensive HIV prevention package that included regular HIV testing, sexual health and adherence promotion using Integrated Next Step Counseling, STI testing, and safety assessments at all visits. At each study visit, participants also completed behavioral assessments via an audio computer-assisted self-interview, received condoms, and were given the study drug.

The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at all participating sites (Supplement 1). Adolescents were allowed to consent to study participation without parental consent and all participants provided written informed consent before undergoing any study procedures. A description of the process to allow adolescent consent has been described elsewhere. Participants were provided compensation for each study visit as determined by each site (range, $50-$75).

Measures

PrEP Acceptability

Assessments of acceptability were conducted at the 12- and 48-week visits using a questionnaire previously used with youth (eg, “How much did you like or not like taking a pill every day?”). Beliefs about PrEP were assessed using questions adapted from the Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative open-label extension study to explore how PrEP may influence the health of participants, condom use, and sexual behavior, as well as reasons that participants would choose not to take PrEP (eg, “If I took PrEP, I would worry it was hurting my health”).

Adherence

The AIDS Clinical Trials Group Adherence Follow-up Questionnaire was adapted to examine the possible reasons for missing PrEP doses and how often doses were missed for those reasons over the past month. Preexposure prophylaxis medication levels were assessed on dried blood spots collected at each visit to quantify intracellular tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP) and emtricitabine triphosphate (FTC-TP) concentrations in red blood cells. Results were translated into the dosing categories that were previously used in PrEP randomized clinical trials with adult MSM. Dosing categories included a below lower limit of quantitation, a lower limit of quantitation to 349 fmol per punch (fewer than 2 tablets per week), 350 to 699 fmol per punch (2-3 tablets per week), and 700 or more fmol per punch (4 or more tablets per week).

Sexual Behavior

A self-report questionnaire was used to assess each participant’s general sexual history, as well as detailed sexual behavior with last partner. Participants were tested for syphilis at baseline and week 48, and as clinically indicated at other visits. Rectal swabs for nucleic acid amplification testing for gonorrhea (GC) and chlamydia (CT) were collected and assayed at baseline, 24 weeks, 48 weeks, and as clinically indicated at other visits. Urine-based nucleic acid amplification testing for GC and CT occurred at every visit. An STI was considered present based on a positive test result for urethral or rectal GC or CT or serologic evidence of syphilis (adjudicated based on current and prior rapid plasma reagin titers and history).

Data and Safety Monitoring

The investigative team monitored the study for clinical adverse events and abnormal laboratory values using the ATN Table for Grading Severity of Adolescent Adverse Events (October 2006–March 2011). Renal safety was monitored by measuring serum creatinine, dipstick urine protein, and glucose levels at each study visit. Bone mineral density (BMD) levels were measured by dual-energy radiography absorptiometry in the hip, spine, and total body at baseline, 24 weeks, and 48 weeks. An external data and safety monitoring board reviewed study safety data at 6-month intervals while the trial was being conducted and uniformly recommended that the study be completed.

Statistical Analysis

The demographic and risk characteristics of the study population at baseline were examined using simple descriptive statistics. Categorical-scaled variables were described using frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were examined in terms of medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Some exploratory analyses were conducted. For example, bivariable relationships between study outcomes and characteristics of interest were examined using the Fisher exact test for categorical characteristics and the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous characteristics when based on comparisons between independent groups. The McNemar test was used when comparing binary measures between time points among participants or using a generalized estimating equations approach for repeated measures to account for correlations among participants; an exchangeable (compound symmetry) correlation structure was assumed. The nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to assess changes in continuous measures between time points among participants.

Cumulative STI incidence rates (and 95% CIs) were estimated separately for the 0- to 24- and 24- to 48-week period using a repeated-measures Poisson regression model; an unstructured correlation was specified in the models. In addition to yielding model-based estimates of the STI incidence rates, this approach also provided a statistical assessment that compared the rates between the study periods. Statistical significance was set at P = .05. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

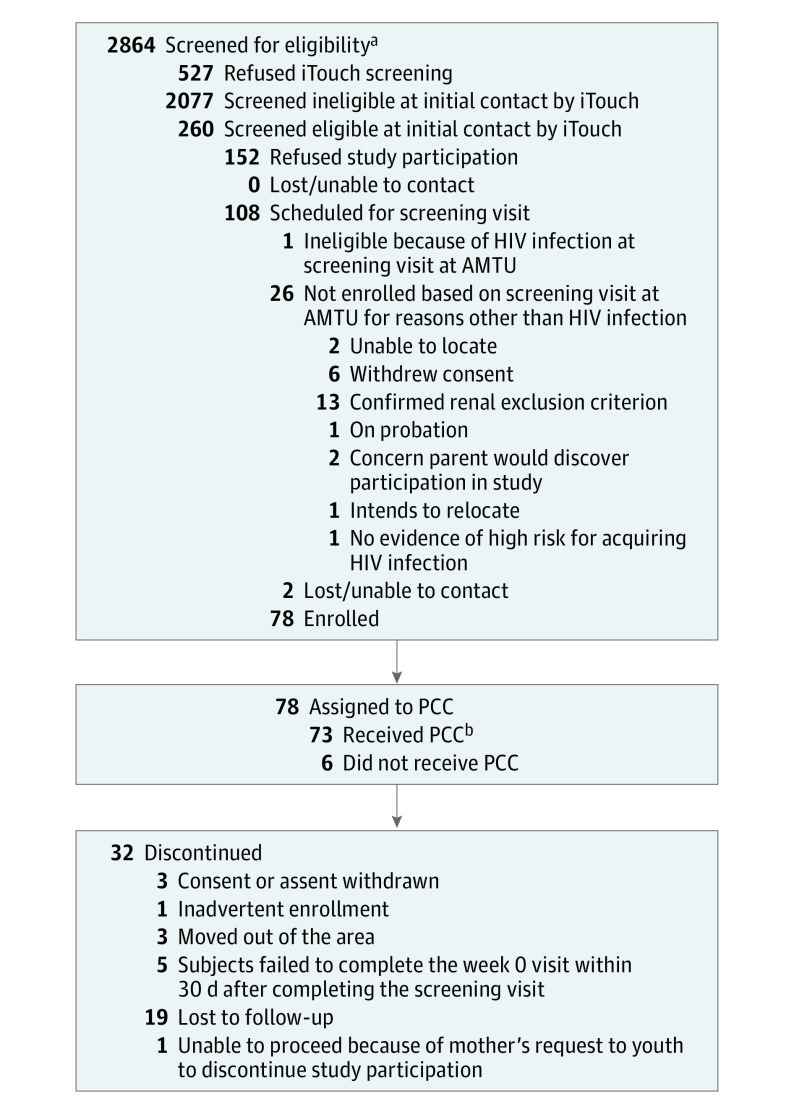

Between August 2013 and September 2014, 78 participants enrolled in the study (Figure 1). Their mean (SD) age was 16.5 (0.73) years, and 23 (29%) self-identified as black/African American, 16 (21%) as white Hispanic, and 26 (33%) as other/mixed race/ethnicity. Most identified as gay (n = 45, 58%) or bisexual (n = 22, 28%). Most (n = 69, 88%) lived with their families and were currently in school (n = 67, 86%). In the month before baseline, 49 participants (67%) reported that they drank alcohol and 47 (64%) reported smoking marijuana. Twelve participants (15%) had been expelled from their homes because of their sexual orientation at some point, and 13 (17%) reported having exchanged sex for money. Twenty-four participants (60%) reported having condomless receptive anal intercourse with their last sexual partner, and 12 (15%) had a prevalent STI at study entry (Table 1).

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Flow Diagram.

Patient progress through enrollment, follow-up, and analysis. HIV indicates human immunodeficiency virus; AMTU, adolescent medicine trial unit; PCC, personalized cognitive counseling.

aSome screening data were lost at 1 site and are not included.

bThe received PPC category represents the number of participants who received the PCC intervention.

Table 1. Demographics.

| Demographic/Risk Characteristic | No. (%) | P Valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 78) |

Completed Study (n = 47) |

Lost to Follow-up (n = 31)a |

||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 16.5 (0.73) | 17.0 (0.73) | 17.2 (0.69) | .36 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (6) | .16 |

| Black/African American | 23 (29) | 15 (32) | 8 (26) | |

| White | 11 (14) | 4 (9) | 7 (23) | |

| White Hispanic | 16 (21) | 10 (21) | 6 (19) | |

| Other/mixed race/ethnicity | 26 (33) | 18 (38) | 8 (26) | |

| How do you identify (sexual orientation)? | ||||

| Straight | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 | .22 |

| Gay | 45 (58) | 25 (53) | 20 (65) | |

| Queer | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Bisexual | 22 (28) | 15 (32) | 7 (23) | |

| Trade | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Questioning | 5 (6) | 1 (2) | 4 (13) | |

| Down low | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 | |

| Are you currently attending school? | ||||

| Yes | 56 (72) | 34 (72) | 22 (71) | .94 |

| No, I have graduated | 6 (8) | 3 (6) | 3 (10) | |

| Yes, but I am on summer/winter/spring break | 11 (14) | 7 (15) | 4 (13) | |

| What is the highest grade you have completed in school? | ||||

| Eighth grade or less | 3 (4) | 3 (6) | 0 | .70 |

| More than eighth grade but did not complete high school | 58 (74) | 34 (72) | 24 (77) | |

| GED | 3 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | |

| High school diploma | 11 (14) | 6 (13) | 5 (16.1) | |

| Some college | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Don't know | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| Refused to answer | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Where are you currently living or staying most of the time? | ||||

| Your own house or apartment | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | .32 |

| At your parent(s) house or apartment | 62 (79) | 39 (83) | 23 (74) | |

| At another family member’s house or apartment | 7 (9) | 5 (11) | 2 (6) | |

| At someone else’s house or apartment | 4 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (10) | |

| Foster home or group home | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| In a rooming, boarding, halfway house, or shelter/welfare hotel | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Have you ever been kicked out or asked to leave the place where you were living by a parent or legal guardian either because you were sexually attracted to/because you were having sex with other males? | ||||

| Yes | 12 (15) | 7 (15) | 5 (16) | <.99 |

| Refused | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Have you ever been paid for sex in your lifetime? | ||||

| Yes | 13 (17) | 10 (21) | 3 (10) | .23 |

| Have you ever exchanged sex for a place to stay? | ||||

| Yes | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | <.99 |

| High-risk sex acts for men with menc | ||||

| Yes | 52 (87) | 34 (89) | 18 (82) | .45 |

| Unprotected receptive anal sex with partnerd | .30 | |||

| Yes | 24 (60) | 15 (54) | 9 (75) | |

| In the past month, how often have you drunk alcohol? | ||||

| Never | 24 (33) | 14 (32) | 10 (34) | .74 |

| Once or twice | 40 (55) | 25 (57) | 15 (52) | |

| Every week | 8 (11) | 5 (11) | 3 (10) | |

| Every day or almost every day | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | |

| In the past month, how often have you got drunk off of alcohol? | ||||

| Never | 16 (33) | 9 (30) | 7 (37) | .88 |

| Once or twice | 31 (63) | 20 (67) | 11 (58) | |

| Every week | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | |

| In the past month, how often have you smoked marijuana? | ||||

| Never | 27 (36) | 17 (38) | 10 (34) | .47 |

| Once or twice | 26 (35) | 15 (33) | 11 (38) | |

| Every week | 7 (9) | 6 (13) | 1 (3) | |

| Every day or almost every day | 14 (19) | 7 (16) | 7 (39) | |

| Tanner stage | ||||

| 3 | 2 (2) | NA | ||

| 4 | 20 (26) | |||

| 5 | 56 (72) | |||

Abbreviations: ACASI, audio computer-assisted self-interview; GED, general educational development; NA, not applicable.

Lost to follow-up during the course of the study; included in analyses up to point of loss.

P values obtained from the Fisher exact test for categorical measures and the nonparametric Wilcoxon 2-sample test for continuous measures.

Coded as yes if provided value greater than 0 when asked how many male partners they had unprotected oral or anal sex with within the last month in the Risk Behavior and Disinhibition section of the ACASI Interview.

Coded as yes if value greater than 0 obtained based on difference in responses to questions asking about the number of times in the last month they had receptive anal sex with their last partner minus the number of times in the last month they had receptive anal sex with their partner in which their partner used a condom.

Five participants failed to complete the week 0 visit within 30 days of screening and were prematurely discontinued from the study. Seventy-two participants (92%) began daily oral TDF/FTC and 46 (64%) of these completed 48 weeks of follow-up. Reasons for noncompletion are shown in Figure 1. Eight participants remained in study follow-up but chose to discontinue TDF/FTC.

Safety

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine was well tolerated overall and there were no confirmed laboratory abnormalities assessed as related to the study product. One participant permanently discontinued TDF/FTC because of grade 3 weight loss, which was assessed as possibly related to the study product. There were no renal events, elevations in serum creatinine levels, or bone fractures. Reasons for grade 3 or higher adverse events regardless of relations to the study product are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Adverse Event Grading.

| Diagnosis | Grade of Events | Total AE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| AEs Related to Study Drugs | ||||||

| Total participants who experienced events | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Unintentional weight loss | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 |

| Total events | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 |

| AEs Not Related to Study Drugs | ||||||

| Total participants who experienced events | NA | NA | 7 | 2 | NA | 7 |

| Appendicitis | NA | NA | NA | 1 | NA | 1 |

| Cellulitis of finger | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| ≥10% Weight loss from baseline | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| Unintentional weight loss | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| Hypokalemia | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| Left arm pain | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| Seizure | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| Depression | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | 1 |

| Suicidal ideation | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | NA | 2 |

| Total events | NA | NA | 8 | 2 | NA | 10 |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; NA, not applicable.

Dual-energy radiography absorptiometry scanning was performed in 75 participants. The mean baseline BMD was in the normal range for age, based on z scores (standard deviations adjusted for race/ethnicity and age and median −0.1, −0.1, and −0.2 in the spine, hip, and total body, respectively). At 48 weeks, results were available for 43 participants, for whom there were statistically significant increases from baseline in BMD in the spine (median 2.6%; IQR, 0.0-4.6; P < .001), hip (1.2%; IQR, −0.9 to 4.3; P = .02), and total body (0.7%; IQR, −0.2 to 2.6; P < .001). z Scores in the hip and spine did not change significantly from baseline to 48 weeks, but the total body BMD z score decreased (−0.20; IQR, −0.3 to 0.0; P < .001). Exploratory subgroup analyses revealed no statistically significant differences in change in BMD between participants with 48-week dried blood spot TFV-DP levels commensurate with 4 or more doses per week (>700 fmol/punch; n = 10), when compared with changes in those with levels associated with fewer than 2 doses per week (<350 fmol/punch; n = 24), or those with no evidence of recent dosing (below lower limit of quantification; n = 17).

Sexual Behavior

At baseline, study participants reported a median of 1.0 (IQR, 1-3) male sexual partners in the past month. Numbers of sexual partners and condomless sex acts did not change significantly over time (eTable in the Supplement 2). Before PrEP initiation, 19 prevalent STIs were diagnosed in 14 participants (5 rectal GC, 8 rectal CT, 4 urine CT, and 2 syphilis). Over 48 weeks of PrEP use, 23 STIs were diagnosed in 12 participants (6 rectal GC, 8 rectal CT, 5 urine CT, 3 urine GC, and 1 syphilis). Sexually transmitted infection incidence rates that were estimated based on a Poisson regression model were higher in the first 24 weeks of the study (18.1/100 person-years; 95% CI, 9.7-34.0) compared with weeks 24 to 48 of the study (9.4/100 person-years; 95% CI, 3.4-25.6), but not significantly so (rate ratio, 1.93; 95% CI, 0.62-5.96; P = .25).

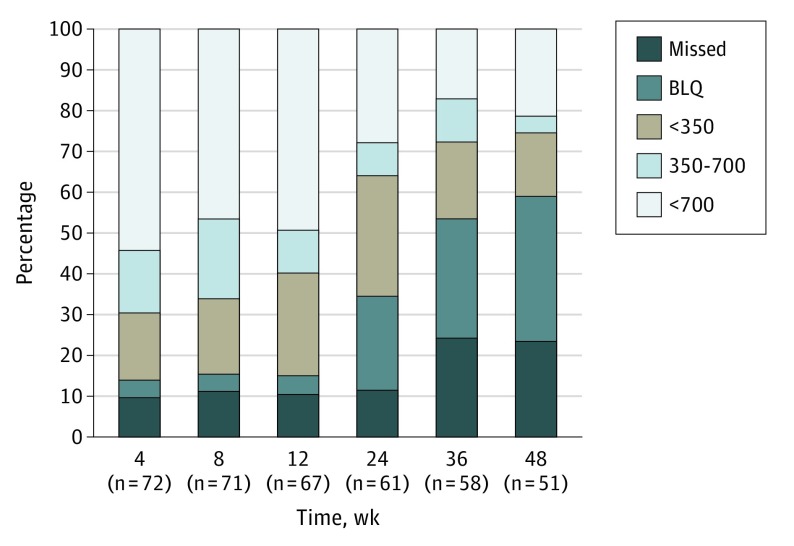

Adherence

Adherence as measured by TFV-DP is depicted in Figure 2. Most participants had detectable drug levels throughout the study period, with more than 95% of participants having detectable levels over the first 12 weeks of treatment with declining levels thereafter. Among the 72 participants who were prescribed PrEP at the 0-week visit and who continued to participate in the study, levels of TFV-DP that were associated with high levels of protection against rectal HIV exposure (ie, consistent with taking a mean of 4 pills or more per week [>700 fmol/punch]) were found in 42 (54%), 37 (47%), 38 (49%), 22 (28%), 13 (17%), and 17 (22%) participants at weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48, respectively. Based on generalized estimating equations modeling, there were no statistically significant associations between condomless sex or condomless receptive anal intercourse with last partner and TFV-DP levels over time (P > .40, data not shown).

Figure 2. Adherence via Tenofovir Diphosphate in Dried Blood Spots.

BLQ indicates below the lower limit of quantitation.

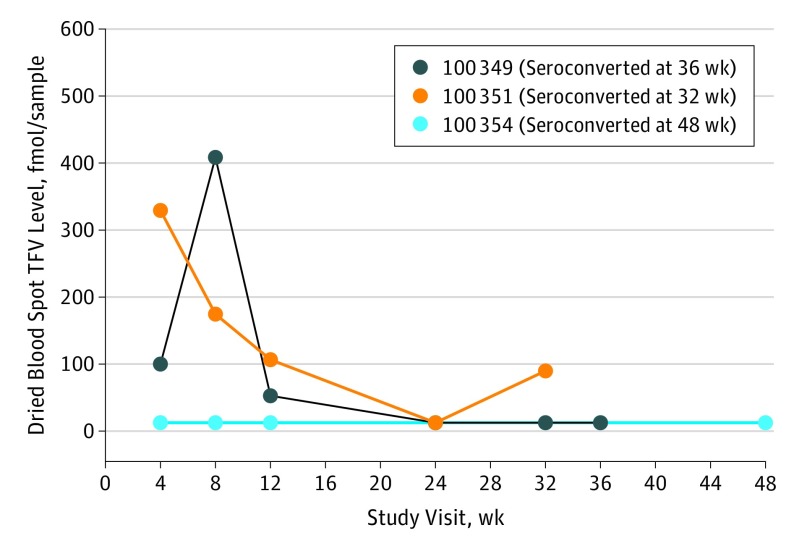

Three participants acquired an HIV infection during study follow-up: 1 each at 32, 36, and 48 weeks for an annualized HIV incidence of 6.4 (95% CI, 1.3-18.7) infections per 100 person-years. Tenofovir diphosphate levels for seroconverters are shown in Figure 3 and are all consistent with taking fewer than a mean of 2 doses per week at the likely time of HIV acquisition. No genotypic mutations conferring resistance to tenofovir or emtricitabine were detected by consensus sequencing at the time of diagnosis.

Figure 3. Tenofovir Diphosphate Levels Among Seroconverters.

TFV indicates tenofovir diphosphate.

Compared with participants with protective levels of TFV-DP, those without protective levels were more likely to endorse the statement “I worry others will see me taking pills and think I am HIV-positive” (baseline, 4 participants [22.2%]; week 48, 5 participants [29.4%]; P = .03). The most commonly reported reasons for missing doses of the study medication were being away from home (n = 105, 32%), being too busy (n = 91, 28%), forgetting (n = 85, 26%), and changes in routine (n = 61, 18%). Participants could contribute more than once to the reporting of each reason. The acceptability of the pill size and pill taste decreased from 12 weeks to 48 weeks (“Liked a lot” range, 6 [10.2%] to 3 [7.1%]; P = .06; and “Liked a lot” range, 3 [5.0%] to 1 [2.4%]; P = .002; respectively), coincident with declines in biomarkers of adherence.

Discussion

To our knowledge, ATN 113 is the first study on the safety and implementation of PrEP among adolescent MSM. This study demonstrates that adolescents who are at risk for HIV and therefore likely to benefit from PrEP can be enrolled in a biomedical HIV prevention clinical trial. A major challenge of this study was to ensure safe and unfettered access for at-risk minors to provide consent for their own participation in a clinical trial and to contribute crucial data for licensure.

Acceptability ratings of PrEP, the overall study, and the study components were high. Preexposure prophylaxis was well tolerated by participants with no documented discontinuations because of adverse effects and no confirmed abnormal laboratory results. Peak bone mass, which is a potent predictor of fractures in later life is typically not achieved until late adolescence or early adulthood, so we expected to see overall increases in BMD among young men aged 15 to 17 years. On the other hand, the slight but statistically significant decline in total body BMD z score suggests that growth may have been less than would be predicted among this age group. The apparent lack of a strong association of change in BMD with magnitude of TFV exposure (week 48 dried blood spot TFV-DP levels) differs from results seen among adult MSM who use PrEP. However, we would caution that the relatively small sample size, coupled with the competing forces of bone growth and TDF-associated bone loss, make it difficult to draw conclusions about the effects of TDF on bone density levels in this age group. Further study, including follow-up measurements of changes in BMD after discontinuation of PrEP, is warranted to fully assess the potential risks and benefits of using TDF/FTC PrEP in this vulnerable population.

The incidence of STIs decreased among participants, but the HIV incidence rate was high compared with other open-label clinical trials in the United States and almost twice the rate found in the companion ATN 110 study that enrolled MSM who were aged 18 to 22 years. Those who had seroconversion had very low levels of drugs detected, if any, at the time of seroconversion. These results continue to strengthen and support the conclusion of the data that PrEP works when taken according to the prescribed dose.

Challenges with adherence to medication are commonplace among adolescents, regardless of whether it is adherence to a treatment or prevention regimen. Nonadherence among youth is often a reflection of both the biological and behavioral transitions that occur during this developmental time, including increased autonomy from parents/caregivers, increased importance of peers and corresponding vulnerability to peer influence and stigma, and an undeveloped cognitive capacity for organization and planning. Furthermore, low perceived HIV risk has been associated with low adherence in prevention clinical trials. Thus, it is not surprising that a proportion of adolescents in this study were unable to adhere with enough frequency to confer high levels of HIV protection. However, most participants were able to take at least 2 doses per week as estimated by TFV-DP levels, indicating that they were attempting to adhere to the regimen, albeit with less frequency than prescribed. Of critical importance will be the development and testing of long-acting PrEP agents for HIV prevention among adolescents that would likely reduce (although not eliminate) the adherence issues that are associated with daily pills.

A noticeable trend in the adherence data from this study, also seen in ATN 110, is the striking drop in TFV-DP levels once participants began the quarterly visit schedule. We have suggested that an augmented visit schedule, or at least the option of additional visits, might be most appropriate for youth. Indeed, this approach would be consistent with the US contraceptive practice recommendations, which already recognize that adolescents are a special population who might benefit from more frequent follow-up than adults. Additional developmentally appropriate methods of sustaining PrEP engagement and adherence include more frequent interactions via mobile technology for medication reminders or supportive check-ins, adherence support through clubs or groups, peer buddies, and other youth-focused methods of service delivery.

In addition to addressing the individual-level barriers to adherence, more work is needed to address community-level barriers, such as the stigma and homophobia associated with PrEP. A Kaiser Foundation survey found that 84% of youth aged 15 to 24 years reported recognizing stigma around HIV in the United States and other studies have found that black MSM were more likely than other MSM to report experiencing PrEP-related stigma, as well as sexuality-related stigma. Anticipatory stigma from sexual partners has also been reported as a barrier to PrEP use. These multifaceted experiences with stigma ultimately limit access to PrEP for those who may benefit from it the most.

To our knowledge, ATN 113 is the first adolescent-specific PrEP clinical trial to be completed, but it will certainly not be the last, and there is much work to do. We need to better understand the barriers to adherence and develop more effective ways to enhance adherence for youth who are clinically prescribed PrEP. More research is needed to explore PrEP knowledge, the accuracy of risk perception, stigmas, and access problems among adolescents, as well as clinician competence.

For youth who are vulnerable to HIV infection, biomedical tools need to be leveraged and integrated with behavioral interventions. While it may be challenging to enroll youth into biomedical clinical trials, if youth are not enrolled then they cannot benefit from the regulatory approval of these life-saving tools. Conversely, if they are simply used off-label without the support of contextual and biomedical data from such trials, then the safest and most appropriate manner in which to use these tools in youth will remain unclear and barriers to access could become insurmountable.

Limitations

This study has several limitations to be considered when interpreting the results. The small sample size of the study, along with lack of participation from some ATN sites, may limit the generalizability of the findings as representative of adolescent MSM in other geographic areas or sociodemographic categories. In addition, while rectal swabs and urine were collected for STI testing in this study, we did not conduct pharyngeal testing and samples were only routinely collected at baseline, 24 weeks, and 48 weeks. This sampling strategy may ultimately have underestimated the rates of STIs among this sample. Finally, the time and resources that were needed to conduct this study were substantial and may limit the ability to replicate these findings in future clinical trials.

Conclusions

The high incidence rates of HIV and STIs among YMSM, along with the lack of any significant safety signals from this study, strongly support the need for an adolescent PrEP indication for TDF/FTC. The waning adherence, especially with quarterly visits, demonstrates that more time, attention, and resources may need to be allocated to adolescents who are seeking prevention services. Developmentally appropriate visit schedules within adolescent-friendly service facilities will be important additions to PrEP implementation programs.

Trial Protocol

eTable. Sexual Risk Behaviors by Study Visit—Median and Interquartile Range

References

- 1.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. ; iPrEx Study Team . Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. ; Partners PrEP Study Team . Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. ; TDF2 Study Group . Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. ; iPrEx study team . Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. . Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. . Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(1):75-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare CB, et al. . Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in a large integrated health care system: adherence, renal safety, and discontinuation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):540-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Health for the World’s Adolescents: A Second Chance in the Second Decade. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS Global AIDS update. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/Global-AIDS-update-2016. Accessed January 27, 2017.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV among youth fact sheet. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/age/youth/cdc-hiv-youth.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2017.

- 11.Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, et al. . New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(3):629-637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dilley JW, Woods WJ, Loeb L, et al. . Brief cognitive counseling with HIV testing to reduce sexual risk among men who have sex with men: results from a randomized controlled trial using paraprofessional counselors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(5):569-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chianese C, Amico KR, Mayer K, et al. . Integrated next step counseling for sexual health promotion and medication adherence for individuals using pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(S1):A159. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.5329.abstract [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilbert AL, Knopf AS, Fortenberry JD, Kapogiannis BG, Hosek S, Zimet GD. Adolescent self-consent for biomedical human immunodeficiency virus prevention research. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(1):113-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knopf AS, Gilbert AL, Zimet GD, et al. . Moral conflict and competing duties in the initiation of a biomedical HIV prevention trial with minor adolescents [published online October 21, 2016]. AJOB Empir Bioeth. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2016.1251506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosek SG, Siberry G, Bell M, et al. ; Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV Interventions . Project PrEPare (ATN 082): the acceptability and feasibility of an HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trial with young men who have sex with men (YMSM). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):447-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chesney MA, Morin M, Sherr L. Adherence to HIV antiretroviral medicine. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1599-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Zheng JH, Rower JE, et al. . Tenofovir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir diphosphate in dried blood spots for determining recent and cumulative drug exposure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(2):384-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon CM, Zemel BS, Wren TA, et al. . The determinants of peak bone mass. J Pediatr. 2017;180:261-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zemel BS, Kalkwarf HJ, Gilsanz V, et al. . Revised reference curves for bone mineral content and areal bone mineral density according to age and sex for black and non-black children: results of the bone mineral density in childhood study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(10):3160-3169. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulligan K, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, et al. ; Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative Study Team . Effects of emtricitabine/tenofovir on bone mineral density in HIV-negative persons in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):572-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosek SG, Rudy B, Landovitz R, et al. ; Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) for HIVAIDS Interventions . An HIV preexposure prophylaxis demonstration project and safety study for young MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):21-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson KA, Baeten JM, Mugo NR, Bekker LG, Celum CL, Heffron R. Tenofovir-based oral PrEP prevents HIV infection among women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. . US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(RR-4):1-66. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6504a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosek S, Celum C, Wilson CM, Kapogiannis B, Delany-Moretlwe S, Bekker LG. Preventing HIV among adolescents with oral PrEP: observations and challenges in the United States and South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(7)(suppl 6):21107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaiser Family Foundation National survey of teens and young adults on HIV/AIDS. http://www.kff.org/hivaids/poll-finding/national-survey-of-teens-and-young-adults/. Accessed January 27, 2017.

- 27.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Golub SA. Enhancing PrEP access for black and Latino men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(5):547-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Philbin MM, Parker CM, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Garcia J, Hirsch JS. The promise of pre-exposure prophylaxis for black men who have sex with men: an ecological approach to attitudes, beliefs, and barriers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(6):282-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biello KB, Oldenburg CE, Mitty JA, et al. . The “safe sex” conundrum: anticipated stigma from sexual partners as a barrier to PrEP use among substance using MSM engaging in transactional sex. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):300-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable. Sexual Risk Behaviors by Study Visit—Median and Interquartile Range