Key Points

Question

What is the cost-effectiveness of the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor evolocumab in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease?

Findings

In this study, a Markov cohort state-transition model determined that adding evolocumab at current list price to patients receiving standard background therapy was estimated to cost $268 637 per quality-adjusted life-year gained. Sensitivity and scenario analyses demonstrated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios ranging from $100 193 to $488 642 per quality-adjusted life-year.

Meaning

To achieve a threshold of $150 000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of at least 70 mg/dL and an annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years, an annual net price of $9669 or a higher risk population would need to be treated.

Abstract

Importance

The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor evolocumab has been demonstrated to reduce the composite of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. To our knowledge, long-term cost-effectiveness of this therapy has not been evaluated using clinical trial efficacy data.

Objective

To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of evolocumab in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease when added to standard background therapy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A Markov cohort state-transition model was used, integrating US population-specific demographics, risk factors, background therapy, and event rates along with trial-based event risk reduction. Costs, including price of drug, utilities, and transitional probabilities, were included from published sources.

Exposures

Addition of evolocumab to standard background therapy including statins.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Cardiovascular events including myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke and cardiovascular death, quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), and net value-based price.

Results

In the base case, using US clinical practice patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of at least 70 mg/dL (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259) and an annual events rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years, evolocumab was associated with increased cost and improved QALY: incremental cost, $105 398; incremental QALY, 0.39, with an ICER of $268 637 per QALY gained ($165 689 with discounted price of $10 311 based on mean rebate of 29% for branded pharmaceuticals). Sensitivity and scenario analyses demonstrated ICERs ranging from $100 193 to $488 642 per QALY, with ICER of $413 579 per QALY for trial patient characteristics and event rate of 4.2 per 100 patient-years ($270 192 with discounted price of $10 311) and $483 800 if no cardiovascular mortality reduction emerges. Evolocumab treatment exceeded $150 000 per QALY in most scenarios but would meet this threshold at an annual net price of $9669 ($6780 for the trial participants) or with the discounted net price of $10 311 in patients with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels of at least 80 mg/dL.

Conclusions and Relevance

At its current list price of $14 523, the addition of evolocumab to standard background therapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease exceeds generally accepted cost-effectiveness thresholds. To achieve an ICER of $150 000 per QALY, the annual net price would need to be substantially lower ($9669 for US clinical practice and $6780 for trial participants), or a higher-risk population would need to be treated.

This study evaluates the cost-effectiveness of evolocumab in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease when added to standard background therapy.

Introduction

Despite major advances in the treatment of patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), substantial risk of recurrent cardiac events, stroke events, and cardiovascular death remains as well as high disease burden affecting quality of life and costs.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 Lowering low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels with certain therapies, including statins, reduces cardiovascular events.8,9 Yet, many patients with established ASCVD need further LDL cholesterol lowering and remain at substantial risk for cardiovascular events despite optimal statin therapy.1,4,9 In the past 5 years, monoclonal antibodies that inhibit proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) have demonstrated marked LDL cholesterol level lowering. Evolocumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against PCSK9, lowers LDL cholesterol by approximately 60%.10,11,12,13 The evolocumab cardiovascular outcomes trial, Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk (FOURIER),14 demonstrated that the addition of evolocumab to standard background therapy, including moderate- to high-intensity statin therapy, reduced incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with established ASCVD.

Cost-effectiveness of new therapies is important as health care costs rise, and accurate information about value and potential tradeoffs among therapies is essential. Several analyses have assessed the potential economic value of PCSK9 inhibitors in patient populations with varied risk levels,7,15,16,17,18 extrapolating cardiovascular event reduction rate ratios per 38.67 mg/dL of LDL cholesterol reduction observed in the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaboration (CTTC) meta-analyses of statin trials (to convert LDL cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259).8,19,20 To our knowledge, the FOURIER results provide the first opportunity to assess cost-effectiveness of evolocumab for the reduction of subsequent cardiovascular events in an ASCVD population using specific PCSK9 inhibition trial-based efficacy data.

In this study, a Markov cohort state-transition model was used to assess the cost-effectiveness of evolocumab when added to standard background therapy in clinical practice patients with established ASCVD from a societal and US health plan perspective to help better identify the patient populations and value-based price where the use of evolocumab treatment would provide value.

Methods

Model Structure

A Markov cohort state-transition model was used, considering the US societal perspective and assuming lifetime horizon to capture the lifetime progression of ASCVD in adults. A similar model to that used previously to estimate cost-effectiveness and value-based price range of evolocumab using LDL cholesterol–lowering data from the statin trials and cardiovascular event reduction from CTTC meta-analyses7,17 was used. The model (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) was used to predict subsequent cardiovascular events and cardiovascular- or noncardiovascular-related mortality as a function of age, sex, LDL cholesterol level, and cardiovascular event history. The model transition-states were adapted to match those analyzed in FOURIER.14 The model comprises mutually exclusive health states that include ASCVD, 2 acute event states (myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke for a 1-year duration), and postevent health states and their combination that are introduced to enable the model to account for event recurrence. In addition, distinctions are made between cardiovascular and noncardiovascular death. Revascularization is included as a procedure and not as a separate health state because it is assumed that it does not affect cardiovascular event risk or quality of life.

Patient Population

A representative clinical practice-based population with established ASCVD was modeled to embody the US patient population. Patients were selected from the US population–weighted National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys based on individuals 18 years or older (mean age, 66 years) with a recorded atherosclerotic cardiovascular condition and LDL cholesterol level of at least 70 mg/dL (mean, 104 mg/dL) while receiving statin therapy (Table 1). Written informed consent was obtained from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey participants. The survey was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics ethics review board.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Patient Population in the FOURIER Trial and US Population From NHANES.

| Characteristic | FOURIER Trial | NHANES | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL | LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 63 (9) | 66 (11) | 64 (12) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 20 795 (75) | 4 942 898 (61) | 1 983 383 (59) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |||

| White | 23 426 (85) | 6 395 502 (78) | 2 483 397 (74) |

| Black or African American | 699 (2) | 659 089 (8) | 378 565 (11) |

| Asian or other | 3439 (12) | 1 109 929 (14) | 483 231 (14) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, No. (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 22 040 (80) | 6 082 104 (74) | 2 576 980 (77) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9333 (34) | 2 102 232 (26) | 913 607 (27) |

| Current cigarette use | 7770 (28) | 2 083 283 (26) | 682 855 (20) |

| History of vascular disease, No. (%)a | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 22 356 (71) | 4 233 427 (52) | 1 481 045 (44) |

| Ischemic stroke | 5330 (17) | 2 793 056 (34) | 909 851 (27) |

| Other ASCVD | 3640 (12) | 1 138 038 (14) | 954 297 (29) |

| Ezetimibe use, No. (%) | 1393 (5) | 571 044 (7) | 178 285 (5) |

| Lipid parameters at parent study baseline | |||

| LDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 97 (28) | 104 (28) | 130 (27) |

| LDL-C 70-99 mg/dL, No. (%) | 15 586 (57) | 4 819 328 (59) | 0 |

| LDL-C ≥100 mg/dL, No. (%) | 9943 (36) | 3 345 193 (41) | 3 345 193 (100) |

| HDL-C, mean (SD), mg/dL | 46 (13) | 50 (12) | 48 (11) |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dL | 149 (70) | 138 (74) | 164 (85) |

Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; FOURIER, Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

SI conversion factor: To convert cholesterol levels to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113.

Percentage split in the history of vascular disease is calculated using the total number of previous events, rather than the total number of study participants, as is used for the other characteristics.

The Truven MarketScan database, a large-scale database of claims for commercially insured patients and patients with Medicare Supplemental insurance, was used to estimate contemporary cardiovascular event rates for US patients with ASCVD.15 However, cardiovascular-related death data were not complete in MarketScan. Cardiovascular mortality rates were estimated by combining multiple National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys death files (2004-2012) and National Vital Statistics Report 2012.15 Rates were adjusted by baseline LDL cholesterol levels and age and previous event history.21 Ten-year and lifetime event rates for this population are shown in eTable 1 in the Supplement. These rates reflect multiple events. For reference, the annual cardiovascular event rate (nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death) was 6.4 per 100 patient-years in this US practice-based population, whereas in participants in the FOURIER trial placebo plus standard background therapy arm, the event rate (including multiple events) was 4.2 per 100 patient-years (eTable 2 in the Supplement).14 The noncardiovascular mortality rate was assumed to be that of the general US population.22

Intervention Effects and Model Assumptions

Hazard ratios were based on landmark analysis of the individual end points in FOURIER of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal ischemic stroke, and coronary revascularization, with respective risk reductions of 21%, 26%, and 16% in the first year and 36%, 25%, and 28% beyond year 1 (Table 2), as previously published.14 Cardiovascular event rate ratios per 38.67 mg/dL of LDL cholesterol reduction were derived from the hazard ratios and the LDL cholesterol reduction reported in the trial (53.36 mg/dL) and then applied in the model (Table 2). In FOURIER, cardiovascular mortality reduction was not observed within the first 3 years of follow-up. In the base case, risk reduction for cardiovascular mortality was set at 0% for the first 5 years and then estimated to proportionally match the cardiovascular mortality event reduction in the CTTC meta-analysis8 for overall or more vs less intensive statin therapy when appropriate thereafter (risk reduction 9.5% per 38.67 mg/dL LDL cholesterol reduction) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The 5-year delay before the emergence of cardiovascular mortality reduction was selected in the base case to be consistent with findings from contemporary greater-intensity LDL cholesterol–lowering clinical outcome trials in which cardiovascular mortality reduction was not observed in the first 5 years.9,27,28 Consistent with the safety profile reported in FOURIER, among patients receiving evolocumab, 2.1% were assumed to develop mild injection site reactions over 2 years, resulting in a small quality-of-life decrement (Table 2). Evolocumab therapy persistence rates over time were based on those observed in FOURIER during the first 3 years of follow-up and then kept steady. Within-trial persistence and adherence effects on efficacy were already reflected in the intention-to-treat hazard ratios reported in FOURIER during the first 3 years and modeled as not further varying.

Table 2. Key Inputs in the Model.

| Input | Value (95% CI) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Event rate per 100 patient-years, clinical practice population | ||

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 2.3 (2.2-2.4) | US Claims Data, NHANES, NVS15 |

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke | 2.1 (2.0-2.2) | |

| Cardiovascular-related death | 2.0 (1.9-2.1) | |

| Coronary revascularizationa | 3.3 (3.1-3.4) | |

| Event rate per 100 patient-years, trial population | ||

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 2.5 (2.2-2.7) | FOURIER14 |

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | |

| Cardiovascular-related death | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | |

| Coronary revascularizationa | 3.9 (3.6-4.3) | |

| Intervention effect, hazard ratiob | ||

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction, 1 y/beyond 1 y | 0.79 (0.67-0.93)/0.64 (0.54-0.76) | FOURIER14 |

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke, 1 y/beyond 1 y | 0.74 (0.55-1.00)/0.75 (0.58-0.98) | |

| Coronary revascularization,a 1 y/beyond 1 y | 0.84 (0.74-0.96)/0.72 (0.63-0.82) | |

| Intervention effect, rate ratio per 38.67 mg/dL LDL-C reduction | ||

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction, 1 y/beyond 1 y | 0.84 (0.75-0.95)/0.72 (0.64-0.82) | FOURIER, CTTC (2010)8,14 |

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke, 1 y/beyond 1 y | 0.80 (0.65-1.00)/0.81 (0.67-0.99) | |

| Coronary revascularization,a 1 y/beyond 1 y | 0.88 (0.80-0.97)/0.79 (0.72-0.87) | |

| Cardiovascular-related death, up to y 5/beyond 5 y | NAc/0.90 (0.85-0.95) | |

| Direct cost, $ | ||

| Other ASCVD | 8501 (7870-9132) | US Claims Data23,24 |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction, year 1/beyond 1 y | 52 084 (50 659-53 510)/8501 (7870-9132) | |

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke, year 1/beyond 1 y | 46 207 (44 063-48 351)/8816 (7573-10 058) | |

| Cardiovascular-related death | 76 537 (75 405-77 669) | |

| Coronary revascularizationa | 59 384 (58 463-60 306) | |

| Indirect cost, $ | ||

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction | 57 936 (56 351-59 522) | AHA Cardiovascular Disease Burden Report25 |

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke | 37 465 (35 727-39 204) | |

| Utilityd | ||

| Established ASCVD | 0.824 (0.800-0.848) | Time Tradeoff Study26 |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction, 1 y/beyond 1 y | 0.672 (0.625-0.719)/0.824 (0.800-0.848) | |

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke, 1 y/beyond 1 y | 0.327 (0.264-0.390)/0.524 (0.472-0.576) | |

| Injection site reaction, disutility | 0.0003 | |

| Discontinuation, % | 15 over 3 y | FOURIER14 |

Abbreviations: AHA, American Heart Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CTTC, Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaboration; FOURIER, Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys; NVS, Novartis, LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Coronary revascularization was defined as percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft.

Hazard ratios are converted to rate ratios per 38.67 mg/dL using: rate ratio per 38.67 mg/dL = exp(LN[hazard ratio]/[53.36/38.67]) or equivalently: rate ratio per 38.67 mg/dL = hazard ratio^(1/[53.36/38.67]), where 53.36 is the LDL-C reduction in mg/dL observed in FOURIER.

No reduction in cardiovascular mortality in first 5 years assumed in the base case.

In utilities, 0 represents death, and 1 represents perfect health.

Costs and Utilities

Direct medical costs associated with cardiovascular events were obtained through US claims data23,24 and adjusted for inflation to January 2017 using the Consumer Price Index.29 Indirect cost estimates were obtained from the 2017 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association report on cardiovascular disease burden by applying reported ratios of direct and indirect costs.25 Noncardiovascular death events were assumed to incur no costs and not vary by treatment allocation. Medication cost of evolocumab in the base case was based on the current wholesale acquisition cost for evolocumab, $14 523 (list price). Additional analyses were performed based on the estimated mean annual net cost of $10 311 (list price minus an average rebate of 29% for branded pharmaceuticals).30 The average of Red Book prices and the market share of generic simvastatin and atorvastatin were used for standard therapy ($68) and ezetimibe ($2780).31 Additional analyses used ezetimibe priced similarly to generic statin therapy ($68). Utility estimates for cardiovascular health states were based on results of a time tradeoff study.26

Base-Case Cost-effectiveness Analysis

The lifetime cost and quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) accrued under the 2 treatment options, evolocumab added to standard background therapy (moderate- to high-intensity statin with or without ezetimibe) vs standard background therapy alone, were projected through simulation. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated as the incremental cost per QALY gained. The analysis considered a cost-effectiveness threshold of $150 000 per QALY gained in the base case, aligned with the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association statement on cost/value methods for intermediate vs low value,32 recommendations from the World Health Organization,33 and contemporary literature.34 The annual net value–based price to achieve an ICER of $150 000 per QALY gained was calculated. A range of willingness-to-pay thresholds were also considered.34,35 Additional model outcomes included the probabilistic mean and 95% credible intervals for the net value–based price. The QALY and costs were discounted at an annual rate of 3.0%, consistent with the Second US Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine recommendation.35

Sensitivity and Scenario Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to reflect uncertainty in model inputs and to assess robustness of model outcomes. In the deterministic sensitivity analyses, model parameter values (Table 2) were varied individually through plausible ranges (eg, 95% confidence intervals). Probabilistic sensitivity analyses examined the combined effect of parameter uncertainty on the model results. A sensitivity analysis was performed using the FOURIER patient population characteristics and cardiovascular event rates analyses. We also analyzed in the clinical practice population analyses where the background cardiovascular event rates were 25% and 50% higher or lower of those in US clinical practice. As a sensitivity analysis, a range of cardiovascular mortality effect sizes were applied to assess the effect on overall results (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Additional sensitivity analyses included extreme cases where all hazard ratios were increased or decreased simultaneously by 1 SE.

A range of scenario analyses were considered including modeling a 3-year, 7-year, or infinite delay of treatment effect on cardiovascular mortality; modeling treatment effect on myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality based on the corresponding key secondary end point from FOURIER; and modeling cost-effectiveness confined to patients with ASCVD with baseline LDL cholesterol levels of at least 100 mg/dL (mean, 130 mg/dL). A scenario analysis was performed where the risk ratios derived from the FOURIER key secondary end point did not vary from year 1 and subsequent years. In addition, scenario analyses with ezetimibe priced similarly to generic statin therapy ($68), where all patients with ASCVD were treated with ezetimibe and statin therapy and where only the US payer perspective was considered (no indirect costs) were performed. We also analyzed what LDL cholesterol treatment initiation threshold for the population would yield an ICER of $150 000 per QALY gained at current list price and current net drug price (value-based LDL-cholesterol treatment initiation threshold). Furthermore, we determined the annual event rate thresholds where the current list price and net price of evolocumab would yield an ICER of $150 000.

The model was developed using Microsoft Excel 2013, version 14.0 (Microsoft). The Impact Inventory Template and the Reporting Checklist for Cost-effectiveness Analyses from the Second Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine35 are in eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement.

Results

In the base case using a US clinical practice patient population, the LDL cholesterol level was at least 70 mg/dL (mean, 104 mg/dL) and the cardiovascular event rate was 6.4 per 100 patient-years with standard background therapy. In this base case, mean lifetime costs would be $234 877 per patient treated with standard therapy and $340 275 per patient treated with evolocumab added to standard background therapy, with incremental costs of $105 398 (Table 3; eTable 6 in the Supplement). The lifetime QALY was 7.23 with standard background therapy and 7.62 with evolocumab, with a difference in health effects of 0.39 QALY. Compared with standard background therapy alone, use of evolocumab at its current list price ($14 523) results in an ICER of $268 637 per QALY gained (Table 3). If, instead, a net price of evolocumab reflecting a 29% discount was used ($10 311), the ICER would be $165 689 per QALY. To achieve a value threshold of $150 000 per QALY gained, a value-based net price of $9669 annually would be required (Table 3). The net value-based prices at ICERs of $50 000, $100 000, $150 000, $200 000, and $250 000 per QALY would be $5578, $7623, $9669, $11 715, and $13 760 per year, respectively. For the FOURIER trial participants, the ICER would be $413 579 per QALY, and the net value-based price would be $6780 (Table 3). Net value-based prices at ICERs of $50 000, $100 000, $150 000, $200 000, and $250 000 per QALY would be $3843, $5312, $6780, $8249, and $9718 per year, respectively.

Table 3. Total Costs, QALY, and ICER.

| Base Case and Sensitivity Analyses | Cost, $ | QALY | ICER, $ | VBP, $a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Incremental | Total | Incremental | |||

| Base case, full list price, US clinical practice | ||||||

| Standard therapy alone | 234 877 | NA | 7.23 | NA | NA | NA |

| Evolocumab added to standard therapy | 340 275 | 105 398 | 7.62 | 0.39 | 268 637 | 9669 |

| Discounted net price, US clinical practice | ||||||

| Standard therapy alone | 234 877 | NA | 7.23 | NA | NA | NA |

| Evolocumab added to standard therapy | 299 884 | 65 007 | 7.62 | 0.39 | 165 689 | 9669 |

| Full list price, FOURIER trial participants | ||||||

| Standard therapy alone | 228 015 | NA | 9.59 | NA | NA | NA |

| Evolocumab added to standard therapy | 367 833 | 139 817 | 9.93 | 0.34 | 413 579 | 6780 |

| Discounted net price, FOURIER trial participants | ||||||

| Standard therapy alone | 228 015 | NA | 9.59 | NA | NA | NA |

| Evolocumab added to standard therapy | 319 358 | 91 343 | 9.93 | 0.34 | 270 192 | 6780 |

Abbreviations: FOURIER, Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; NA, not applicable; QALY, quality-adjusted life-years; VBP, value-based price.

Value-based price is net annual price to achieve an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $150 000 per quality-adjusted life-years.

Sensitivity Analyses

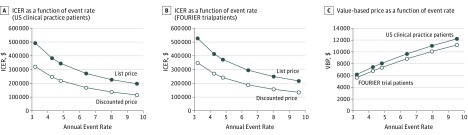

When we varied the background cardiovascular event rates for the US clinical practice population by 25% and 50% higher or lower, the ICER ranged from $194 551 to $488 642 per QALY, and the net value-based price ranged from $12 218 to $6164 (Table 4 and Figure). Testing the treatment benefit for cardiovascular mortality beginning after 5 years of follow-up across risk reductions ranging from 14.0% to 6.4% per 38.67 mg/dL LDL cholesterol yielded an ICER range from $225 575 to $313 163 per QALY and a net value-based price range from $10 773 to $8872 (Table 4). Deterministic sensitivity analyses are presented in eFigure 2 in the Supplement. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses at list price revealed a mean ICER of $275 124 per QALY and a mean net value-based price of $9565, with 95% of values between $6313 and $12 418. The probabilistic mean and 95% credible intervals of the net value-based prices are shown in eFigure 3 in the Supplement.

Table 4. Sensitivity and Scenario Analyses.

| Scenario | Base-Case Assumption | Scenario Assumption | ICER, $ | VBP, $a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| List Price | Discounted Net Price | ||||

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | A reduction of 6.4% in CV mortality per 38.67 mg/dL LDL-C reduction | 313 163 | 191 539 | 8872 |

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | A reduction of 14.0% in CV mortality per 38.67 mg/dL LDL-C reduction | 225 575 | 140 688 | 10 773 |

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | 3-y delay in CV mortality benefit | 245 066 | 151 983 | 10 221 |

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | 7-y delay in CV mortality benefit | 293 720 | 180 258 | 9188 |

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | No CV mortality benefit | 483 800 | 290 601 | 7246 |

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | Key secondary end point in FOURIER | 160 934 | 106 567 | 13 676 |

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | Individual end point for nonfatal MI and nonfatal IS with benefit the same in all years | 286 577 | 182 226 | 9010 |

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | All HRs varied 1 SE lower simultaneously | 193 260 | 114 202 | 12 218 |

| Intervention effect | Individual end point for nonfatal MI, nonfatal IS, and RV from FOURIER; benefit less in first year and greater in second year and beyond; 5-year delay in CV mortality benefit | All HRs varied 1 SE higher simultaneously | 429 364 | 275 893 | 6856 |

| Price of ezetimibe, $ | Net price, 2780 | Net price, 68 | 268 441 | 165 493 | 9677 |

| Ezetimibe use in all patients | Ezetimibe use in 7% | All patients treated with statin and ezetimibe as background therapy | 271 313 | 168 365 | 9560 |

| Annual event rates from FOURIER | Annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years | Annual event rate of 4.2 per 100 patient-years | 413 579 | 270 192 | 6780 |

| Annual event rates 25% lower US practice | Annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years | Annual event rate of 4.8 per 100 patient-years | 341 974 | 216 762 | 8065 |

| Annual event rates 25% higher US practice | Annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years | Annual event rate of 8.0 per 100 patient-years | 224 401 | 134 510 | 11 037 |

| Annual event rates 50% lower US practice | Annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years | Annual event rate of 3.2 per 100 patient-years | 488 642 | 318 010 | 6164 |

| Annual event rates 50% higher US practice | Annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years | Annual event rate of 9.6 per 100 patient-years | 194 551 | 113 142 | 12 218 |

| Perspective | Societal | Payer (exclude indirect cost) | 304 392 | 201 444 | 8206 |

| LDL-C threshold, mg/dL | LDL-C ≥70 | LDL-C ≥100 (mean, 130) | 172 194 | 100 193 | 13 225 |

| Annual event rate threshold | Annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years | Annual event rate to be cost-effective at current list price, 13.5 per 100 patient-years | 150 000 | 80 210 | 14 523 |

| Annual event rate threshold | Annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years | Annual event rate to be cost-effective at current list price 7.1 per 100 patient-years | 246 303 | 150 000 | 10 311 |

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; FOURIER, Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk; HR, hazard ratio; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; IS, ischemic stroke; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI, myocardial infarction; RV, coronary revascularization; VBP, value-based price.

SI conversion factor: To convert LDL-C to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259.

Value-based price is net annual price to achieve an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $150 000 per quality-adjusted life-years.

Figure. Incremental Cost-effectiveness Ratios and Value-Based Pricing by Annual Cardiovascular Event Rates.

A, Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) values for a range of annual cardiovascular event rates per 100 patient-years using full list price ($14 523 per year) and discounted net price ($10 311 per year) for evolocumab for the US clinical practice population. Annual cardiovascular event rate per 100 patient-years integrates multiple events into the rates (patients may experience more than 1 event). B, ICER values for a range of annual cardiovascular event rates per 100 patient-years using full list price ($14 523 per year) and discounted net price ($10 311 per year) for evolocumab for the FOURIER trial population. C, Value-based prices (VBPs) at range of annual cardiovascular event rates per 100 patient-years for the US clinical practice population and for the FOURIER trial participants.

Scenario Analyses

We tested various assumptions of the treatment benefit (Table 4). A 3-year time before cardiovascular mortality benefits emerge yielded an ICER of $245 066 and a value-based net price of $10 221 per year. A 7-year delay in the cardiovascular mortality treatment benefit yielded an ICER of $293 720 per QALY, and a net value-based price of $9188 per year. In the case of no lifetime cardiovascular mortality reduction, the ICER was $483 800 per QALY, and the net value-based price was $7246. This reflects the improvements in the rate of subsequent events, health state utilities (the quality of the life-years), and cardiovascular disease events and procedures costs by reducing nonfatal events, even in the absence of direct survival benefit. Additional scenarios are shown in Table 4. If all patients were receiving ezetimibe and statin therapy, then the ICER was $271 313. When only the US payer perspective was integrated into the model, then the ICER was $304 392 per QALY, and the net value-based price was $8206. At current list price, the LDL cholesterol treatment initiation threshold for patients with ASCVD that would yield an ICER of $150 000 per QALY was calculated to be at least 119 mg/dL (at this threshold, mean LDL cholesterol level for the ASCVD population is 144 mg/dL) and at the discounted price at least 80 mg/dL (at this threshold, mean LDL cholesterol level for the ASCVD population is 110 mg/dL). The annual event rate for the ASCVD population that would yield an ICER of $150 000 per QALY was calculated to be 13.5 per 100 patient-years at list price and 7.1 per 100 patient-years at the discounted price.

Discussion

In this study, a model based on the clinical risk reduction demonstrated in FOURIER and extrapolated over lifetime was used to investigate the economic value of evolocumab in a US clinical practice–based population of patients with established ASCVD. This evaluation has found that evolocumab at its current list price of $14 523, when added to standard background therapy, including statins, in patients with established ASCVD with a background event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years had an ICER of $268 637. This ICER exceeds the threshold established by the World Health Organization for cost-effectiveness and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association threshold for intermediate vs low value.32,33 The ICER would be substantially higher if cardiovascular mortality benefits with evolocumab were not to emerge or if the cardiovascular event rates were similar to those in FOURIER. Evolocumab therapy could meet the threshold of $150 000 per QALY with an annual value-based price of $9669 for a population with an event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years. This evaluation provides insights as to the economic implications of evolocumab therapy if applied to eligible patients with ASCVD in US clinical practice.

Sensitivity and scenario analyses resulted in ICERs that, with few exceptions, exceeded the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association intermediate value and World Health Organization cost-effectiveness thresholds. However, a value-based net annual price of $9669 would yield an ICER of $150 000 per QALY in an ASCVD clinical practice population.32,33 The treatment effect on cardiovascular mortality in the base case is supported by data from mendelian randomization analyses demonstrating virtually identical lower odds of coronary heart disease mortality in patients with lifelong genetically mediated lower LDL cholesterol levels either from variants in 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase or in PCSK9.36 In the scenario that no cardiovascular mortality benefit was to emerge, the ICER would be $483 800 per QALY gained, substantially exceeding current intermediate value and cost-effectiveness thresholds. The base case reflects the characteristics and event rates of patients with ASCVD in US clinical practice. If the characteristics and event rates are similar to those in FOURIER, treatment with evolocumab would lead to an ICER of $413 579 and a value-based net annual price of $6780.

Despite significantly higher medication costs, the incremental reduction in cardiovascular events, corresponding reductions in hospitalizations, and revascularizations resulting from the addition of evolocumab therapy drives the ICER. In patients with established ASCVD who, with other currently available lipid-modifying therapies including maximally tolerated statins, require additional LDL cholesterol lowering, adding evolocumab could facilitate improved clinical outcomes for a considerable proportion of patients.15,16 Substantial population health improvements and further progress toward reduction in noncommunicable diseases could result.15 However, with an ICER of $268 637 per QALY with the current list price, there are legitimate concerns regarding the appropriate allocation of health care resources along with challenges in coverage and access to this therapy, despite demonstration of clinical event reduction in FOURIER. Adopting a net value-based price of $9669 annually would be 1 potential strategy that could affect the value proposition and willingness to pay. Targeting a subset of patients with ASCVD who are at particularly high risk for events based on clinical factors, formal risk scores, or use of a higher LDL cholesterol treatment initiation threshold for the addition of evolocumab therapy would be alternative approaches to improve value and limit expenditures.16 At an LDL cholesterol treatment initiation threshold of at least 100 mg/dL, evolocumab therapy would be cost-effective with an ICER of $100 193 per QALY for a US clinical practice ASCVD population, with an event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years, but only at a net price of $10 311.

This study provides, to our knowledge, the first cost-effectiveness data on evolocumab integrating the results of FOURIER. Prior cost-effectiveness analyses of PCSK9 inhibition have been published based on the projected benefits of LDL cholesterol lowering on clinical events, with variable findings.15,16,17 A prior analysis using a similar model from a US payer perspective suggested therapy at list price was cost-effective for patients with established ASCVD and LDL cholesterol levels of 100 mg/dL or higher.17 In contrast, a study using the Coronary Heart Disease Policy model from a US payer/health system perspective concluded that PCSK9 inhibition was not cost-effective.16 Several methodological differences may account for the discrepancies in these prior modeling studies and the Coronary Heart Disease Policy model may underestimate event risk overall.37,38 The policy model did not consider indirect costs.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The results should be interpreted within the context of the data inputs and modeling assumptions used. Clinical outcomes data from FOURIER were limited to a median follow-up of 26 months, yet model predictions are based on the assumption that clinical benefits extend beyond the period with direct follow-up. If the clinical benefits differ from those modeled in this study, particularly in regards to the magnitude and timing of cardiovascular mortality reductions, the cost-effectiveness findings could be affected by overestimating or underestimating the cost-effectiveness of evolocumab therapy. Cost-effectiveness estimates could also be altered if significant adverse events materialize beyond 3 to 4 years of observation to date.39 If the levels of persistence with and adherence to evolocumab therapy differ from those in FOURIER, costs and clinical effectiveness may be affected. This economic evaluation included indirect costs to apply the US societal perspective, as is preferred,32 but detailed data on indirect costs for each conditional state are limited. This analysis is only applicable to US patients with established ASCVD and is not generalizable to primary prevention patients, other populations at lower cardiovascular event risk, or patients outside the United States.

Conclusions

At its current list price of $14 523, the addition of evolocumab to standard background therapy in patients with ASCVD provides a treatment option that exceeds generally accepted cost-effectiveness thresholds. To achieve an ICER of $150 000 per QALY gained in a US clinical practice ASCVD population with an annual event rate of 6.4 per 100 patient-years, a price reduction with a net annual price of $9669 or with an annual net price of $10 311 targeting treatment in patients with LDL cholesterol levels of 80 mg/dL or higher would be needed. For the FOURIER trial participants, with an annual event rate of 4.2 per 100 patient-years, a net annual price of $6780 would be necessary. These findings highlight the need for a comprehensive disease management approach for ASCVD that includes vigorous lifestyle changes, assiduous adherence to all guideline-directed therapies, and judicious use of new, more costly therapies.

eTable 1. Population Event Rates per 100 Patients from US Clinical Practice Population (Standard Background Therapy vs. Evolocumab plus Standard Background Therapy)

eTable 2. Population Event Rates per 100 Patients from FOURIER Trial Population (Standard Background Therapy vs. Evolocumab plus Standard Background Therapy)

eTable 3. Derivation of Model Inputs for Cardiovascular Death

eTable 4. Impact Inventory for Cost-effectiveness Analysis

eTable 5. Reporting Checklist for Cost-effectiveness Analysis

eTable 6. Derivation of Incremental Costs, Life-Years, and QALY Gained using the Base-Model Assumptions

eFigure 1. Markov Cohort-State Transition Model Diagram

eFigure 2. Markov Cohort-State Transition Model Diagram Tornado Diagram Based on Deterministic Sensitivity Analyses.

eFigure 3. Value-Based Price Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis (Mean and 95% Credible Intervals)

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. ; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis KL, Meyers J, Zhao Z, McCollam PL, Murakami M. High-risk atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in a real-world employed Japanese population: prevalence, cardiovascular event rates, and costs. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22(12):1287-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henk HJ, Paoli CJ, Gandra SR. A retrospective study to examine healthcare costs related to cardiovascular events in individuals with hyperlipidemia. Adv Ther. 2015;32(11):1104-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jernberg T, Hasvold P, Henriksson M, Hjelm H, Thuresson M, Janzon M. Cardiovascular risk in post-myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real world data demonstrate the importance of a long-term perspective. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(19):1163-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Punekar RS, Fox KM, Richhariya A, et al. Burden of first and recurrent cardiovascular events among patients with hyperlipidemia. Clin Cardiol. 2015;38(8):483-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hallberg S, Gandra SR, Fox KM, et al. Healthcare costs associated with cardiovascular events in patients with hyperlipidemia or prior cardiovascular events: estimates from Swedish population-based register data. Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17(5):591-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toth PP, Danese M, Villa G, et al. Estimated burden of cardiovascular disease and value-based price range for evolocumab in a high-risk, secondary-prevention population in the US payer context. J Med Econ. 2017;20(6):555-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. ; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. ; IMPROVE-IT Investigators . Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387-2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blom DJ, Hala T, Bolognese M, et al. ; DESCARTES Investigators . A 52-week placebo-controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1809-1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson JG, Nedergaard BS, Rogers WJ, et al. ; LAPLACE-2 Investigators . Effect of evolocumab or ezetimibe added to moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy on LDL-C lowering in patients with hypercholesterolemia: the LAPLACE-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1870-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raal FJ, Stein EA, Dufour R, et al. ; RUTHERFORD-2 Investigators . PCSK9 inhibition with evolocumab (AMG 145) in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (RUTHERFORD-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9965):331-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al. ; Open-Label Study of Long-Term Evaluation against LDL Cholesterol (OSLER) Investigators . Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(16):1500-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. ; FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators . Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jena AB, Blumenthal DM, Stevens W, Chou JW, Ton TG, Goldman DP. Value of improved lipid control in patients at high risk for adverse cardiac events. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(6):e199-e207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazi DS, Moran AE, Coxson PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2016;316(7):743-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandra SR, Villa G, Fonarow GC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of LDL-C lowering with evolocumab in patients with high cardiovascular risk in the United States. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(6):313-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arrieta A, Page TF, Veledar E, Nasir K. Economic evaluation of PCSK9 inhibitors in reducing cardiovascular risk from health system and private payer perspectives. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. ; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators . The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):581-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fulcher J, O’Connell R, Voysey M, et al. ; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration . Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;385(9976):1397-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson PW, D’Agostino R Sr, Bhatt DL, et al. ; REACH Registry . An international model to predict recurrent cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2012;125(7):695-703.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias E. United States life tables, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(7):1-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonafede MM, Johnson BH, Richhariya A, Gandra SR. Medical costs associated with cardiovascular events among high-risk patients with hyperlipidemia. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:337-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox KM, Wang L, Gandra SR, Quek RG, Li L, Baser O. Clinical and economic burden associated with cardiovascular events among patients with hyperlipidemia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Heart Association Cardiovascular disease: a costly burden for America. Projections through 2035. http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_491543.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- 26.Matza LS, Stewart KD, Gandra SR, et al. Acute and chronic impact of cardiovascular events on health state utilities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen TR, Faergeman O, Kastelein JJ, et al. ; Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering (IDEAL) Study Group . High-dose atorvastatin vs usual-dose simvastatin for secondary prevention after myocardial infarction: the IDEAL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(19):2437-2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armitage J, Bowman L, Wallendszus K, et al. ; Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in Cholesterol and Homocysteine (SEARCH) Collaborative Group . Intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol with 80 mg versus 20 mg simvastatin daily in 12,064 survivors of myocardial infarction: a double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1658-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer price index. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed May 9, 2017.

- 30.Credit Suisse Global equity research major pharmaceuticals: global pharma. https://research-doc.credit-suisse.com/docView?language=ENG&format=PDF&source_id=csplusresearchcp&document_id=1047911451&serialid=hfXhzuK6sK6xRrBsMZzLqZ96QTl7v2YM0kkwWJRGRVU=. Published 2015. Accessed April 15, 2017.

- 31.Pandya A, Sy S, Cho S, Weinstein MC, Gaziano TA. Cost-effectiveness of 10-year risk thresholds for initiation of statin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2015;314(2):142-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson JL, Heidenreich PA, Barnett PG, et al. ACC/AHA statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(21):2304-2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organisation Cost effectiveness and strategic planning (WHO-CHOICE). http://www.who.int/choice/cost-effectiveness/en/. Accessed March 30, 2017.

- 34.Neumann PJ, Cohen JT, Weinstein MC. Updating cost-effectiveness: the curious resilience of the $50,000-per-QALY threshold. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):796-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ference BA, Robinson JG, Brook RD, et al. Variation in PCSK9 and HMGCR and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2144-2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinstein MC, Coxson PG, Williams LW, Pass TM, Stason WB, Goldman L. Forecasting coronary heart disease incidence, mortality, and cost: the Coronary Heart Disease Policy Model. Am J Public Health. 1987;77(11):1417-1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones DS, Greene JA. The contributions of prevention and treatment to the decline in cardiovascular mortality: lessons from a forty-year debate. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(10):2250-2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koren MJ, Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, et al. Long-term low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering efficacy, persistence, and safety of evolocumab in treatment of hypercholesterolemia: results up to 4 years from the open-label OSLER-1 extension study. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(6):598-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Population Event Rates per 100 Patients from US Clinical Practice Population (Standard Background Therapy vs. Evolocumab plus Standard Background Therapy)

eTable 2. Population Event Rates per 100 Patients from FOURIER Trial Population (Standard Background Therapy vs. Evolocumab plus Standard Background Therapy)

eTable 3. Derivation of Model Inputs for Cardiovascular Death

eTable 4. Impact Inventory for Cost-effectiveness Analysis

eTable 5. Reporting Checklist for Cost-effectiveness Analysis

eTable 6. Derivation of Incremental Costs, Life-Years, and QALY Gained using the Base-Model Assumptions

eFigure 1. Markov Cohort-State Transition Model Diagram

eFigure 2. Markov Cohort-State Transition Model Diagram Tornado Diagram Based on Deterministic Sensitivity Analyses.

eFigure 3. Value-Based Price Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis (Mean and 95% Credible Intervals)