This cluster randomized clinical trial examines whether a modified Hospital Elder Life Program reduces incident delirium and length of stay in older patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

Key Points

Question

Does a modified Hospital Elder Life Program reduce incident delirium and hospital length of stay in patients undergoing abdominal surgery?

Findings

In this cluster randomized clinical trial of 377 older patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery, postoperative delirium occurred in fewer patients in the intervention group than in the control group. Hospital length of stay was also significantly shorter in the intervention group.

Meaning

The modified Hospital Elder Life Program strongly may benefit older patients undergoing abdominal surgery, with significant reduction of delirium incidence and hospital length of stay.

Abstract

Importance

Older patients undergoing abdominal surgery commonly experience preventable delirium, which extends their hospital length of stay (LOS).

Objective

To examine whether a modified Hospital Elder Life Program (mHELP) reduces incident delirium and LOS in older patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

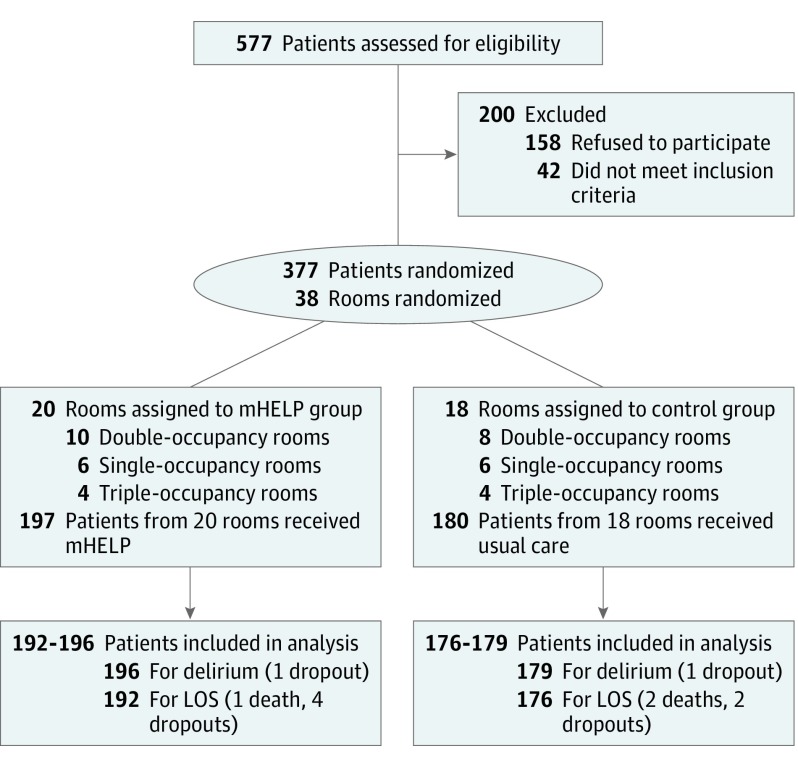

This cluster randomized clinical trial of 577 eligible patients enrolled 377 older patients (≥65 years of age) undergoing gastrectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and colectomy at a 2000-bed urban medical center in Taipei, Taiwan, from August 1, 2009, through October 31, 2012. Consecutive older patients scheduled for elective abdominal surgery with expected LOS longer than 6 days were enrolled, with a recruitment rate of 65.3%. Participants were cluster randomized by room to receive the mHELP or usual care.

Interventions

The intervention (implemented by an mHELP nurse) consisted of 3 protocols administered daily: orienting communication, oral and nutritional assistance, and early mobilization. Intervention group participants received all 3 mHELP protocols postoperatively, in addition to usual care, as soon as they arrived in the inpatient ward and until hospital discharge. Adherence to protocols was tracked daily.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Presence of delirium was assessed daily by 2 trained nurses who were masked to intervention status by using the Confusion Assessment Method. Data on LOS were abstracted from the medical record.

Results

Of 577 eligible patients, 377 (65.3%) were enrolled and randomly assigned to the mHELP (n = 197; mean [SD] age, 74.3 [5.8] years; 111 [56.4%] male) or control (n = 180; mean [SD] age, 74.8 [6.0] years; 103 [57.2%] male) group. Postoperative delirium occurred in 13 of 196 (6.6%) mHELP participants vs 27 of 179 (15.1%) control individuals, representing a relative risk of 0.44 in the mHELP group (95% CI, 0.23–0.83; P = .008). Intervention group participants received the mHELP for a median of 7 days (interquartile range, 6–10 days) and had a shorter median LOS (12.0 days) than control participants (14.0 days) (P = .04).

Conclusions and Relevance

For older patients undergoing abdominal surgery who received the mHELP, the odds of delirium were reduced by 56% and LOS was reduced by 2 days. Our findings support using the mHELP to advance postoperative care for older patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01045330.

Introduction

Patients undergoing abdominal surgery often develop delirium, which greatly influences their postoperative course of clinical recovery and length of hospital stay (LOS). Delirium affects 13% to 50% of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, and the health care costs attributable to delirium are more than $164 billion per year in the United States. Older surgical patients (≥65 years of age) have a particularly high risk for developing delirium, with detrimental effects on their recovery. Delirium has been associated with alterations in cholinergic activity, inflammatory processes induced by neural signaling, and excessive depth of anesthesia and sedation. Delirium may also be precipitated by factors such as infection, malnutrition, electrolyte and fluid imbalances, anemia, and social isolation. Nevertheless, 30% to 40% of cases of delirium are preventable; thus, implementing effective interventions to prevent incident delirium and reduce LOS is a clinical priority.

We hypothesized that delirium and LOS would be reduced by protocols such as orienting communication (ie, orientation and engaged conversation), oral and nutritional assistance (ie, brushing teeth, oral-facial exercise, and postoperative dietary education), and early mobilization. These protocols, initially developed in 2008, were modified from the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), which is cost-effective and has been disseminated widely. Our unique innovation was to select 3 core protocols and allow them to be delivered during daily care by trained nursing staff for feasibility and scalability. For this cluster randomized clinical trial (RCT), we evaluated the effects of the modified Hospital Elder Life Program (mHELP) on delirium incidence and LOS in a sample of older patients (≥65 years of age) undergoing major elective abdominal surgery, primarily for resection of malignant tumors. As a subgroup analysis, effects were stratified by type of abdominal surgery.

Methods

Although cluster randomization is less efficient than individual randomization because outcomes can be correlated between clusters (often reflected as the intraclass correlation [ICC]), this design minimizes contamination among participants in different groups by ensuring that all participants in one room belong to the same group. Physicians and hospital staff (surgeons, residents, and nurses) at the study site were aware of a pending nursing intervention study but were masked to study hypothesis, group allocation, and specific protocols of mHELP. Moreover, outcome assessors were masked to group assignment, and room assignments were rerandomized every 20 patients to minimize potential unmasking of the randomization scheme. The trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1. This cluster RCT was approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee at the National Taiwan University Hospital and registered at clinicaltrials.gov.

Patient Selection

Consecutive older patients (≥65 years of age) admitted to two 36-bed gastrointestinal wards of a 2000-bed urban medical center in Taipei, Taiwan, were screened for enrollment from August 1, 2009, through October 31, 2012. Patients were enrolled if they met 2 criteria: scheduled for elective abdominal surgery and expected LOS longer than 6 days. Participants were cluster randomized to groups with an allocation ratio of 1:1 based on a computer-generated list. Cluster randomization by room was necessary because most patient units in Taiwan are double- or triple-occupancy rooms, threatening cross-contamination if patients were individually randomized. This randomization approach was facilitated by both gastrointestinal wards having the same layout: 6 single-occupancy rooms (3 each randomly assigned to the control and mHELP groups), 9 double-occupancy rooms (4 randomly assigned to the control group and 5 to the mHELP group), and 4 triple-occupancy rooms (2 randomly assigned to each group) (Figure 1). Participants in the 38 rooms formed 318 clusters during the 3-year study period. Written informed consent was obtained for every participant in the study, and all study data were deidentified.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Study Diagram.

LOS indicates length of stay; mHELP, modified Hospital Elder Life Program.

Intervention and Usual Care

The intervention (mHELP) was implemented by a trained mHELP nurse (registered nurse who had 2 years of medical-surgical experience and who was trained on site for 1 month before the intervention start) who did not assess any outcomes. The intervention consisted of the daily hospital-based mHELP comprising 3 core nursing protocols: orienting communication, oral and nutritional assistance, and early mobilization (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 2). In addition to usual perioperative care (eAppendix 2 in Supplement 2), participants received all 3 mHELP protocols postoperatively as soon as they arrived in the inpatient ward, immediately after interim intensive care stays, and until hospital discharge. All protocols were tracked daily with adherence rated on a Likert-type scale from 0 (no adherence) to 3 (full implementation and adherence).

Usual care consisted of standard hospital care provided by surgeons, residents, nurses, and physical therapists (as needed) in the general surgery wards. All participants were encouraged to ambulate and did so as tolerated. The mHELP nurses did not provide services to participants assigned to the control group. However, the same attending physicians provided care to participants in the mHELP and control groups.

Study Data

Two outcome assessors specially trained for delirium assessment collected outcome data from Monday through Saturday. Presence of delirium was assessed by the Confusion Assessment Method based on a brief daily cognitive screen and interview to rate 4 core delirium symptoms. Participants were considered to have delirium if they had the first (acute onset and fluctuating course) and second (inattention) core symptoms and the third (altered consciousness) or fourth (disorganized thinking) symptom. The Confusion Assessment Method is a widely used, standardized method for identifying delirium that has a sensitivity of 94% (95% CI, 91%-97%) and a specificity of 89% (95% CI, 85%-94%) compared with clinical expert ratings and an interrater reliability of 0.70 to 1.00. Changes in mental status were also solicited from family members or nurses. The outcome assessors did not communicate with the mHELP nurses and were masked to participants’ intervention status.

Patient characteristics obtained from in-person interviews included age, sex, and educational level. Baseline clinical factors included presurgical Charlson comorbidity index (higher scores indicate greater mortality risk), presurgical cognitive status measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (score range, 0-30; 30 indicates no impairment), functional status measured using the Barthel Index (score range, 0-100; 100 indicates total independence), nutritional status measured using the Mini-Nutritional Assessment (score range, 0-30; 30 indicates normal status), and depressive status measured using the Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form (score range, 0-15; 15 indicates depression). Other clinical data abstracted from medical records included diagnosis (gastric cancer, pancreatic or periampullary cancer, colorectal cancer, or other), malignant tumor (yes/no), tumor stage (0 to IV), type of surgery (total or subtotal gastrectomy; right hemicolectomy; left hemicolectomy, lower anterior resection, or anterior resection; pancreaticoduodenectomy; or other), duration of surgery (minutes), laparoscopic surgery (yes/no), intensive care unit (ICU) admission (yes/no), and length of ICU stay (days). The LOS data were abstracted from the medical record at discharge.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach. All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc) and R software, version 3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Sample characteristics were compared by treatment group at baseline. Data were reported as number (percentage), mean (SD), or median (interquartile range [IQR]) when not normally distributed.

An important feature of cluster RCTs is the extent of within-cluster correlation for end points. The ICC, defined as the ratio of between-cluster variance to total variance, refers to the proportion of variance attributed to the cluster level. The ICC and its 95% CI were calculated for each outcome using the ICCest function in the R software ICC, which adopted the variance components from a 1-way analysis of variance for the calculation. Of note, all ICCs for each outcome (eAppendix 3 in Supplement 2) were not significantly different from 0 and some were even less than 0, suggesting that the true ICCs are small and adjustment for cluster effect is not indicated. We thus analyzed treatment effects using standard statistical methods not accounting for within-cluster correlation. Kaplan-Meier analysis and the log-rank test were further used to compare the cumulative incidence of delirium, defined as the probability that delirium would develop during hospitalization, between study groups. All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and P < .05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. To correct for multiple comparisons, the significance of the intervention effect for each of the 5 surgical types was assessed at Bonferroni-corrected P = .01 (0.05/5).

Results

Of 577 eligible patients, 377 (65.3%) were enrolled and randomly assigned to the mHELP (n = 197; mean [SD] age, 74.3 [5.8] years; 111 [56.4%] male) or control (n = 180; mean [SD] age, 74.8 [6.0] years; 103 [57.2%] male) group (Figure 1 and Table 1). The mHELP and control groups did not differ significantly in terms of any baseline characteristics, including presurgical cognitive status or other functional measures. The primary indication for surgery was malignant tumor (178 [90.4%] for the mHELP group vs 165 [91.7%] for the control group; P = .64).

Table 1. Participants’ Baseline Characteristics by Groupa .

| Characteristic | mHELP (n = 197) |

Control (n = 180) |

P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 74.3 (5.8) | 74.8 (6.0) | .38 |

| Male sex | 111 (56.4) | 103 (57.2) | .95c |

| Educational level | |||

| Illiterate | 25 (12.7) | 29 (16.1) | .54c |

| Elementary or middle school | 90 (45.7) | 84 (46.7) | |

| High school and above | 82 (41.6) | 67 (37.2) | |

| Presurgical Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.9) | 1.5 (1.7) | .83 |

| Presurgical Charlson comorbidity index | |||

| 0 | 67 (34.0) | 59 (32.8) | .55c |

| 1 | 49 (24.9) | 51 (28.3) | |

| ≥2 | 81 (41.1) | 70 (38.9) | |

| Presurgical scores, mean (SD) | |||

| Cognitive MMSEd | 27.0 (3.8) | 26.8 (3.1) | .61 |

| Functional BIe | 97.1 (10.1) | 97.7 (6.2) | .50 |

| Nutritional MNAf | 24.7 (3.7) | 24.5 (3.9) | .70 |

| Depressive GDSg | 2.5 (2.6) | 2.7 (2.8) | .49 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Gastric cancer | 39 (19.8) | 41 (22.8) | .78c |

| Pancreatic or periampullary cancer | 28 (14.2) | 24 (13.3) | |

| Colorectal cancer | 111 (56.4) | 102 (56.7) | |

| Otherh | 19 (9.6) | 13 (7.2) | |

| Malignant tumor | 178 (90.4) | 165 (91.7) | .64c |

| Tumor stagei | |||

| 0 | 2 (1.1) | 6 (3.6) | .24c |

| I | 45 (25.3) | 52 (31.5) | |

| II | 54 (30.3) | 35 (21.2) | |

| III | 49 (27.5) | 51 (30.9) | |

| IV | 28 (15.7) | 21 (12.7) | |

| Type of surgeryj | |||

| Total or subtotal gastrectomy | 43 (21.9) | 43 (24.0) | .52c |

| Right hemicolectomy | 32 (16.3) | 32 (17.9) | |

| Left hemicolectomy, LAR, or AR | 67 (34.2) | 67 (37.4) | |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 25 (12.8) | 21 (11.7) | |

| Otherk | 29 (14.8) | 16 (8.9) | |

| Duration of surgery, median (IQR), min | 195 (105) | 213 (98) | .10 |

| Laparoscopy | 84 (42.6) | 93 (51.6) | .10c |

| ICU admission after surgery | 100 (50.8) | 98 (54.4) | .47c |

| Length of ICU stay, mean (SD), d | 2.8 (6.5) | 2.4 (3.8) | .58 |

Abbreviations: AR, anterior resection; BI, Barthel Index; GDS, 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; LAR, lower anterior resection; mHELP, modified Hospital Elder Life Program; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA, Mini-Nutritional Assessment.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of study participants unless otherwise indicated.

Significance was determined by Mann-Whitney test unless otherwise indicated.

Significance determined by χ2 test.

Scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better cognitive status.

Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better independence in activities of daily living.

Scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better nutritional status.

Scores range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms.

Diagnoses included splenic tumor, mesothelioma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, pseudomyxoma peritonei duodenum tumor, distal common bile duct tumor, pancreatic tumor, colon poly, and fistula.

n = 178 for the mHELP group and 165 for the control group.

n = 196 for the mHELP group and 179 for the control group.

Open splenectomy, transverse colon partial resection, Hartmann procedure with adhesiolysis and bladder lithotripsy, abdominoperineal resection, or laparoscopic debulking surgery.

Intervention Adherence

Participants and family caregivers reported positive perceptions of the mHELP protocols. The median start time of the intervention protocols was postoperative day 1 (IQR, 1-3 days), with 120 of 196 participants (61.2%) starting by postoperative day 1 and 173 participants (88.3%) receiving mHELP components no later than postoperative day 3. The reason for the delay in the remaining 23 participants (11.7%) receiving mHELP components later than postoperative day 3 was that their ICU stay was prolonged beyond 3 days. Nevertheless, overall adherence to the protocols was good; 166 participants (84.3%) had mean scores of 2 or higher (range, 0-3), indicating moderately good adherence. Mean adherence scores for orienting communication and early mobilization were slightly higher than for oral and nutritional assistance (2.6 and 2.5 vs 2.3). In total, participants in the mHELP group received a median of 7 days (IQR, 6-10 days) of the mHELP protocols, and the mean (SD) time spent with each participant per session was 34.1 (16.0) minutes (median, 30 minutes; IQR, 25-40 minutes). No adverse events or unintended effects were reported as intervention related in the mHELP group.

Effects on Delirium

During hospitalization, 40 cases (10.6%) of incident delirium occurred in both groups. In the group that received mHELP, delirium developed in 13 cases (6.6%), whereas the control group had 27 cases (15.1%) (Table 2). These differences were statistically significant with a relative risk of 0.44 for delirium (95% CI, 0.23-0.83; P = .008), demonstrating a risk reduction of 56%. In absolute terms, the number of cases needed to treat to prevent 1 case of delirium was 11.8. The mHELP also had significant effects for cumulative incidence of delirium (χ2 = 5.87, P = .02) (Figure 2). Stratified by surgical type, participants who underwent total or subtotal gastrectomy and received mHELP had reduced delirium (1 [2.3%] in the mHELP group vs 8 [18.6%] in the control group; P = .03).

Table 2. Delirium and Length of Hospital Stay Outcomes.

| Characteristic | mHELP | Control | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium, No./total No. (%)b | 13/196 (6.6) | 27/179 (15.1) | .008c |

| Total or subtotal gastrectomy | 1/43 (2.3) | 8/43 (18.6) | .03d |

| Right hemicolectomy | 1/32 (3.1) | 2/32 (6.3) | >.99d |

| Left hemicolectomy, LAR, or AR | 6/67 (9.0) | 10/67 (14.9) | .43d |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 2/25 (8.0) | 6/21 (28.6) | .12d |

| Otherd | 3/29 (10.3) | 1/16 (6.3) | >.99d |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), de | 12.0 (6) | 14.0 (9) | .04 |

| Total or subtotal gastrectomy | 12.0 (5) | 18.0 (17) | <.001 |

| Right hemicolectomy | 12.0 (4) | 13.0 (5.5) | .12 |

| Left hemicolectomy, LAR, or AR | 12.0 (6) | 12.0 (5) | .79 |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 16.0 (12) | 25.5 (25) | .28 |

| Otherf | 12.0 (15) | 13.5 (7.5) | .95 |

Abbreviations: AR, anterior resection; IQR, interquartile range; LAR, lower anterior resection; mHELP, modified Hospital Elder Life Program.

Significance was determined by Mann-Whitney test unless indicated otherwise. Significance of the intervention effect for each of the 5 surgical types was assessed at the Bonferroni-corrected P value of .01 (0.05/5).

n = 196 for the mHELP group and 179 for the control group.

Significance determined by χ2 test.

Significance determined by Fisher exact test.

n = 192 for the mHELP group and 176 for the control group.

Procedures such as open splenectomy, transverse colon partial resection, Hartmann procedure with adhesiolysis and bladder lithotripsy, abdominoperineal resection, and laparoscopic debulking surgery.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of Delirium by Group.

The cumulative incidence of delirium was defined as the probability of the development of delirium during hospitalization. Data on patients were censored at the time of discharge or death. The difference between the groups was significant (χ2 = 5.87; P = .02 by the log-rank test). Because of the smaller sample sizes, the figure does not extend beyond 18 days. mHELP indicates modified Hospital Elder Life Program.

Effects on LOS

The mHELP and control groups differed significantly in median LOS (12.0 vs 14.0 days; P = .04) (Table 2). Stratified by surgical type, participants who underwent total or subtotal gastrectomy had significantly shorter LOS (12.0 vs 18.0 days; P < .001) with mHELP. Delayed implementation of mHELP components in 23 participants (11.7%) was attributable to a prolonged ICU stay of 3 days or longer. In this mHELP subgroup, delirium incidence was lower than that in the control subgroup (4 of 23 [17.4%] vs 6 of 20 [30.0%]), a difference that did not reach significance (P = .47). Moreover, LOS did not differ significantly between these subgroups (21.0 vs 21.0 days; P = .80).

Discussion

The mHELP strongly benefitted older patients undergoing abdominal surgery for resection of malignant tumor, with significant reduction of delirium incidence by 56% and hospital LOS by 2 days. As shown in Figure 2, development of delirium is not only delayed but also reduced for patients who received mHELP. Stratified by surgical type, patients who underwent gastrectomy benefited more from mHELP, with a 6-day shorter LOS than in the control group (12.0 vs 18.0 days; P < .001). This subgroup also experienced a trend toward reduced delirium incidence. The mechanism for this greater benefit in patients undergoing gastrectomy is unclear, requiring further research to understand factors that may magnify or attenuate the mHELP effects and to define the effect of mHELP in various surgical procedures.

Consistent with our RCT findings, a 14-study meta-analysis found that multicomponent, nonpharmacologic interventions including at least 2 to 6 components (ie, cognition, mobilization, hydration, hearing, vision, and sleep-wake cycle) in 4 randomized or matched trials (mostly medical inpatients; one focusing on surgical patients) effectively reduced incident delirium by 44% with a trend toward reducing LOS. The mHELP targets similar components (orienting communication, oral and nutritional assistance, and early mobilization) with a unique extension to brushing teeth and oral-facial exercise to improve dry mouth and swallowing efficacy, thus facilitating oral intake. We postulated that increasing older patients’ attention to and engagement with the postoperative recovery environment, increasing their swallowing efficacy and nutritional and fluid repletion, and augmenting physical activity would prevent delirium and reduce LOS. Future research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms of the intervention effect; possible research areas include neuropsychological measures, such as executive functioning and attention; physiology of swallowing efficacy; nutritional and fluid parameters; or inflammatory markers.

We note that other delirium prevention approaches for older hospitalized adults have included proactive geriatric consultation, training family members, sustained education, and single-component interventions, such as bright light, music therapy, and use of software to detect medications that may cause delirium. Not all studies included surgical patients or documented efficacy in reducing delirium incidence. An important issue noted by researchers in most of these studies was that assuring adherence to the interventions was a key factor for success and was not always achievable across settings.

Indeed, the 3 mHELP protocols might seem commonsensical, yet the key to their effectiveness may lie in their consistent daily application. In this study, we had a full-time–equivalent trained mHELP nurse to consistently deliver all 3 protocols to 196 patients, spending approximately 30 minutes with each patient daily. Thus, with an additional 30 minutes of nursing time per older patient, mHELP reduced delirium by 56% and shortened LOS by 2 days, which will greatly reduce medical costs. By extrapolation, older patients in the United States had 7.96 million surgical hospital stays in 2012, with a mean cost of $11 600 per stay. Thus, mHELP could have prevented approximately 674 576 cases of delirium in the surgical service in 2012, resulting in a Medicare cost savings of approximately $10 000 per case or $6.7 billion for the year. By cutting 2 days from LOS (of 14 days in controls; a 14% reduction), implementation of mHELP could have saved $1624 per hospital stay or $12.9 billion per year in Medicare costs for the hospital stay.

Limitations

Several caveats about this study are worthy of comment. First, we did not adjust for the cluster effect because of very small ICCs, indicating weak between-cluster correlations for each outcome. To gain efficiency, future trials may use individual randomization instead of cluster randomization. Second, with a sample size of 377, post hoc analysis indicated that our study was powered at 81% for delirium and 80% for LOS to detect group differences as a whole but was underpowered for subgroup analyses by surgical type. Third, 9 of 377 participants (2.4% attrition rate, including 3 deaths and 6 dropouts) had missing outcome values, which might have biased the study findings. However, this bias was likely minimized by attrition rates not differing significantly between the intervention and control groups (2.5% vs 2.2%). Fourth, participants from both groups received care from the same surgeons and nurses; that is, some participants in the control group may have received mHELP components through crossover (contamination) effects. However, the effect of this contamination would have underestimated the mHELP effects. Fifth, we did not collect data on postoperative complications, which are important risk factors for delirium and might have also been affected by mHELP and contributed to the study findings. Sixth, our trial was conducted without an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program that involved epidural or regional anesthesia, minimally invasive techniques, fluid and pain management, and aggressive postoperative rehabilitation. Although this omission may limit generalizability to centers using ERAS, mHELP may still present important advantages. For medical centers unable to initiate a full ERAS program, mHELP may be considered to be a useful starting point to advance care for vulnerable older patients. Moreover, for centers with ERAS already implemented, mHELP provides feasible, structured, postoperative care protocols that target cognition, nutrition, and ambulation to augment the ERAS program and enhance recovery.

Conclusions

Delirium, which is recognized as the most common surgical complication in older patients, has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospital stays, higher medical costs, and greater likelihood of institutionalization. Older patients undergoing major abdominal surgery for resection of malignant tumor had markedly reduced rates of incident delirium and shorter LOS when they received mHELP, which included 3 nurse-administered protocols: orienting communication, oral and nutritional assistance, and early mobilization. The key to the effectiveness of the 3 mHELP components is their consistent and daily application, with high adherence rates. Medical centers that want to advance postoperative care for older patients might consider mHELP as a highly effective starting point for delirium prevention.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix 1. Modified Hospital Elder Life Program (mHELP) Standardized Protocols

eAppendix 2. Usual Perioperative Care at the Studied Site

eAppendix 3. Intraclass Correlations (ICCs) for Continuous Outcome End Points

References

- 1.Rudolph JL, Marcantonio ER. Postoperative delirium: acute change with long-term implications. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(5):1202-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Bree SH, Vlug MS, Bemelman WA, et al. Faster recovery of gastrointestinal transit after laparoscopy and fast-track care in patients undergoing colonic surgery. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(3):872-880.e1, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augestad KM, Delaney CP. Postoperative ileus: impact of pharmacological treatment, laparoscopic surgery and enhanced recovery pathways. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(17):2067-2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911-922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leslie DL, Inouye SK. The importance of delirium: economic and societal costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S241-S243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gleason LJ, Schmitt EM, Kosar CM, et al. Effect of delirium and other major complications on outcomes after elective surgery in older adults. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(12):1134-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavallari M, Hshieh TT, Guttmann CR, et al. ; SAGES Study Group . Brain atrophy and white-matter hyperintensities are not significantly associated with incidence and severity of postoperative delirium in older persons without dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(6):2122-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverstein JH. Cognition, anesthesia, and surgery. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2014;52(4):42-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young J, Inouye SK. Delirium in older people. BMJ. 2007;334(7598):842-846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholz AF, Oldroyd C, McCarthy K, Quinn TJ, Hewitt J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for postoperative delirium among older patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2016;103(2):e21-e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CC, Saczynski J, Inouye SK. The modified Hospital Elder Life Program: adapting a complex intervention for feasibility and scalability in a surgical setting. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(5):16-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CC, Lin MT, Tien YW, Yen CJ, Huang GH, Inouye SK. Modified Hospital Elder Life Program: effects on abdominal surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(2):245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CC, Chen CN, Lai IR, Huang GH, Saczynski JS, Inouye SK. Effects of a modified Hospital Elder Life Program on frailty in individuals undergoing major elective abdominal surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(2):261-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inouye SK, Baker DI, Fugal P, Bradley EH; HELP Dissemination Project . Dissemination of the Hospital Elder Life Program: implementation, adaptation, and successes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1492-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin FH, Neal K, Fenlon K, Hassan S, Inouye SK. Sustainability and scalability of the Hospital Elder Life Program at a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(2):359-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hshieh TT, Yue J, Oh E, et al. Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):512-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell MJ. Challenges of cluster randomized trials. J Comp Eff Res. 2014;3(3):271-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method: a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823-830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rofes L, Arreola V, Romea M, et al. Pathophysiology of oropharyngeal dysphagia in the frail elderly. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(8):851-858, e230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: the Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev. 1996;54(1, pt 2)(suppl 2):S59-S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Ath P, Katona P, Mullan E, Evans S, Katona C. Screening, detection and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders, I: the acceptability and performance of the 15 item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15) and the development of short versions. Fam Pract. 1994;11(3):260-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcantonio ER. Postoperative delirium: a 76-year-old woman with delirium following surgery. JAMA. 2012;308(1):73-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald JH. Handbook of Biological Statistics. 3rd ed Baltimore, MD: Sparky House Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y, Lee CF, Cheung YB. Analyzing binary outcome data with small clusters: a simulation study. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2014;43(7):1771-1782. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng CM, Chiu MJ, Wang JH, et al. Cognitive stimulation during hospitalization improves global cognition of older Taiwanese undergoing elective total knee and hip replacement surgery. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(6):1322-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim P, Morris OJ, Nolan G, Moore S, Draganic B, Smith SR. Sham feeding with chewing gum after elective colorectal resectional surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2013;257(6):1016-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ertek S, Cicero A. Impact of physical activity on inflammation: effects on cardiovascular disease risk and other inflammatory conditions. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8(5):794-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dainese R, Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Influence of body posture on intestinal transit of gas. Gut. 2003;52(7):971-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenbloom-Brunton DA, Henneman EA, Inouye SK. Feasibility of family participation in a delirium prevention program for hospitalized older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2010;36(9):22-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez FT, Tobar C, Beddings CI, Vallejo G, Fuentes P. Preventing delirium in an acute hospital using a non-pharmacological intervention. Age Ageing. 2012;41(5):629-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lundström M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, et al. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(3):178-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabet N, Hudson S, Sweeney V, et al. An educational intervention can prevent delirium on acute medical wards. Age Ageing. 2005;34(2):152-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milisen K, Foreman MD, Abraham IL, et al. A nurse-led interdisciplinary intervention program for delirium in elderly hip-fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):523-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abraha I, Trotta F, Rimland JM, et al. Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions to prevent and treat delirium in older patients: a systematic overview. The SENATOR project ONTOP Series. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0123090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young J, Cheater F, Collinson M, et al. Prevention of delirium (POD) for older people in hospital: study protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility trial. Trials. 2015;16:340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greysen SR. Delirium and the “know-do” gap in acute care for elders. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):521-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss A, Elixhauser A Overview of hospital stays in the Unites States, 2012. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2016.

- 44.Leslie DL, Zhang Y, Bogardus ST, Holford TR, Leo-Summers LS, Inouye SK. Consequences of preventing delirium in hospitalized older adults on nursing home costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):405-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicholson A, Lowe MC, Parker J, Lewis SR, Alderson P, Smith AF. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery programmes in surgical patients. Br J Surg. 2014;101(3):172-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults Postoperative delirium in older adults: best practice statement from the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220(2):136-48.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix 1. Modified Hospital Elder Life Program (mHELP) Standardized Protocols

eAppendix 2. Usual Perioperative Care at the Studied Site

eAppendix 3. Intraclass Correlations (ICCs) for Continuous Outcome End Points