This randomized clinical trial evaluates YAG laser vitreolysis vs sham laser for symptomatic Weiss ring floaters from posterior vitreous detachment.

Key Points

Question

Is YAG laser vitreolysis safe and effective in treating patients with symptomatic vitreous floaters in the context of a posterior vitreous detachment?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 52 patients randomized to receive YAG laser vitreolysis vs sham laser vitreolysis, the YAG laser group reported greater improvement in symptoms than the sham group. No clinically relevant adverse events were identified.

Meaning

These results suggest that YAG laser vitreolysis can improve visual symptoms associated with symptomatic vitreous floaters, but larger studies with longer durations are needed to validate these findings and expand the ability to identify adverse events.

Abstract

Importance

Vitreous floaters are common and can worsen visual quality. YAG vitreolysis is an untested treatment for floaters.

Objective

To evaluate YAG laser vitreolysis vs sham vitreolysis for symptomatic Weiss ring floaters from posterior vitreous detachment.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This single-center, masked, sham-controlled randomized clinical trial was performed from March 25, 2015, to August 3, 2016, in 52 eyes of 52 patients (36 cases and 16 controls) treated at a private ophthalmology practice.

Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned to YAG laser vitreolysis or sham YAG (control).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary 6-month outcomes were subjective change measured from 0% to 100% using a 10-point visual disturbance score, a 5-level qualitative scale, and National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire 25 (NEI VFQ-25). Secondary outcomes included objective change assessed by masked grading of color fundus photography and Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study best-corrected visual acuity.

Results

Fifty-two patients (52 eyes; 17 men and 35 women; 51 white and 1 Asian) with symptomatic Weiss rings were enrolled in the study (mean [SD] age, 61.4 [8.0] years for the YAG laser group and 61.1 [6.6] years for the sham group). The YAG laser group reported greater symptomatic improvement (54%) than controls (9%) (difference, 45%; 95% CI, 25%-64%; P < .001). In the YAG laser group, the 10-point visual disturbance score improved by 3.2 vs 0.1 in the sham group (difference, −3.0; 95% CI, −4.3 to −1.7; P < .001). A total of 19 patients (53%) in the YAG laser group reported significantly or completely improved symptoms vs 0 individuals in the sham group (difference, 53%; 95% CI, 36%-69%, P < .001). Compared with sham, NEI VFQ-25 revealed improved general vision (difference, 16.3; 95% CI, 0.9-31.7; P = .04), peripheral vision (difference, 11.6; 95% CI, 0.8-22.4; P = .04), role difficulties (difference, 17.3; 95% CI, 8.0-26.6; P < .001), and dependency (difference, 5.6; 95% CI, 0.5-10.8; P = .03) among the YAG laser group. Best-corrected visual acuity changed by −0.2 letters in the YAG laser group and by −0.6 letters in sham group (difference, 0.4; 95% CI, −6.5 to 5.3; P = .94). No differences in adverse events between groups were identified.

Conclusions and Relevance

YAG laser vitreolysis subjectively improved Weiss ring–related symptoms and objectively improved Weiss ring appearance. Greater confidence in these outcomes may result from larger confirmatory studies of longer duration.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov NCT02897583

Introduction

Floaters become more prevalent with age because of degenerative vitreous changes that occur throughout life. In youth, hyaluronan keeps collagen fibrils separated in the vitreous cavity and thus maintains transparency of the vitreous. However, with time, hyaluronan dissociates from collagen, causing cross-linking and aggregation of collagen with fibrous structures that scatter light—a process known as vitreous liquefaction.

Clinically, a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is often marked by a degree of fibroglial tissue known as a Weiss ring that is free floating over the optic nerve. A PVD allows the vitreous body to move when the head or eye moves, and thus, the Weiss ring and vitreous opacities cast shadows onto the retina that are perceived as floaters.

A PVD is present in approximately 65% of patients reaching the age of 65 years. Although most patients grow accustomed to the visual disturbance associated with Weiss rings and other floaters, many find them bothersome. Floaters can reduce contrast sensitivity and quality of life.

Three management options exist for symptomatic floaters: patient education and observation, pars plana vitrectomy with a 1-incision Intrector (in which a 1-incision, limited core vitrectomy is performed while visualizing through an indirect ophthalmoscope; Insight Instruments) or a standard 3-port vitrector, and YAG vitreolysis.

Existing literature assessing the effect of YAG laser on the properties of rabbit vitreous has suggested that pathologic disruption may occur with laser application in the middle or posterior vitreous. There are limited published studies on the effect of YAG vitreolysis for treating symptomatic floaters in humans. Small, uncontrolled cases series assessing YAG vitreolyisis report some symptomatic success and suggest a good safety profile. No prospective, sham-controlled trials have been performed, to our knowledge. This is particularly important because of the subjective nature of floater-related visual disturbance and the potential of placebo effect confounding the efficacy of treatment. Research by Karickhoff showed the most robust outcomes when treating Weiss rings. Therefore, the current study evaluated YAG vitreolysis in patients with symptomatic Weiss rings.

Methods

Participants

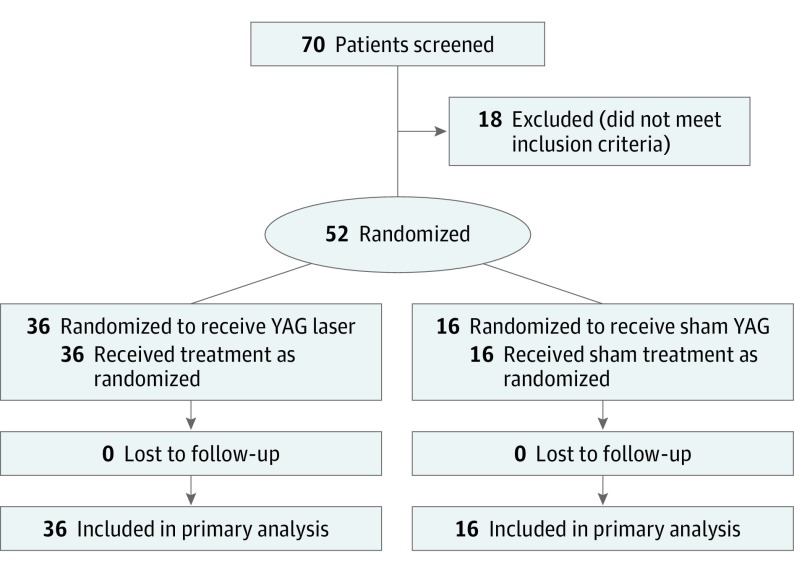

This single-center, masked, sham-controlled randomized clinical trial included 52 patients (35 women and 17 men) at Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston, Boston, Massachusetts, from March 25, 2015, through August 3, 2016. All were patients of the practice with a primary symptom of symptomatic floaters. No patients were billed for participation in the study. Of the 52 participants, 36 were randomly assigned to unilateral treatment with YAG laser vitreolysis, and 16 were assigned to sham YAG vitreolysis (control). All were followed up for 6 months. In all cases, one eye (the eye with the most patient-determined floater-related symptoms) was treated, and the other eye was observed. Patients were assigned to YAG and sham groups in a 2:1 ratio to maximize the number of treated patients and obtain more robust efficacy and safety data for YAG vitreolysis (Figure 1). All patients provided written informed consent before participating in the study, and all data were deidentified. The study was conducted in adherence to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the methods and execution were consistent with the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. Study approval was obtained from the Sterling Institutional Review Board, Atlanta, Georgia. The trial protocol can be found in the Supplement 1.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

A priori sample calculations assumed a modest improvement in symptoms of 30% in the YAG group compared with 10% in the sham group, yielding a sample of 75 patients with an SD of 25%, α of .05, and power of 0.9. A planned interim analysis on January 20, 2016, showed a statistically significant difference among the 13 patients who had completed the study. Thus, the decision was made to schedule no further screening visits beyond those already scheduled, resulting in 52 enrolled patients.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: symptomatic Weiss ring floater secondary to PVD; floater symptom duration of at least 6 months; PVD documented on clinical examination, optical coherence tomography, and B-scan (all performed by the same examiner [one of us, C.P.S.]; if complete PVD was not visible for all 3 modalities, the patient was excluded); a self-rated visual disturbance of at least 4 on a 0- to 10-point scale, with 0 indicating no symptoms and 10 indicating debilitating symptoms; symptomatic Weiss ring (PVD) located at least 3 mm from the retina and 5 mm from the posterior lens capsule of the crystalline lens, as measured on B-scan (patients with pseudophakia had no minimum required distance from the intraocular lens) to maximize safety; ability to undergo YAG laser procedure; and acceptance of associated risks.

Exclusion criteria were Snellen best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) worse than 20/50 in the nonstudy eye; history of retinal tear, retinal detachment, uveitis, diabetic retinopathy, macular edema, retinal vein occlusion, or aphakia in the study eye; and history of glaucoma or high intraocular pressure, defined as a history of glaucoma surgery or currently taking 2 or more topical glaucoma medications in the study eye.

All patients were followed up for 6 months, with clinical examinations performed at postoperative week 1, month 1, month 3, and month 6. The primary outcomes measured at 6 months included subjective percentage of improvement (from 0% to 100%), 10-point visual disturbance score as described by Singh, 5-level qualitative scale described by Delaney et al, and the National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire 25 (NEI VFQ-25). Of these, the NEI VFQ-25 was the only validated self-reporting method. Secondary outcomes included objective change based on masked grading of color wide-angle fundus photography, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) BCVA, and adverse events.

Preoperative Evaluation and Randomization

Before treatment, all patients completed a nonvalidated baseline questionnaire, which asked the following: (1) How long have you had symptomatic floaters? (2) Do you have symptomatic floaters in the right, left, or both eyes? (3) Which eye is more symptomatic: right or left or both equally symptomatic? (4) How many floaters do you have in the more symptomatic eye (or the study eye if both eyes were equally affected)? (5) What activity is most inconvenienced by floater presence? (6) Rate your visual disturbance by floaters on a 0- to 10-point scale, with 0 indicating no symptoms and 10 indicating debilitating symptoms.

Patient age, sex, and lens status were recorded. The ETDRS BCVA was determined preoperatively along with a B-scan. Spectralis optical coherence tomography and infrared photography (Heidelberg Engineering), color photography (Optos plc), and slitlamp and indirect ophthalmoscope examination with scleral depression were conducted at baseline. Status of preexisting macular pathologic findings was not recorded. The same study coordinator administered the NEI VFQ-25 at baseline (and again at month 6) for all patients.

Surgical Procedure

One of us (C.P.S.) performed all the surgical procedures. YAG vitreolysis was performed using the Ultra Q Reflex laser (Ellex Medical). A maximum energy per pulse of 7 mJ was used, as described by Tsai et al. The energy was initially set at 3 mJ and titrated to an appropriate level at which the surgeon observed plasma formation with the creation of gas bubbles. After intraocular pressure was measured, the pupil of the study eye was dilated with phenylephrine, 2.5%, and tropicamide, 1%. Proparacaine was given, and an Ocular Karickhoff 21 mm Vitreous Lens with goniosol was applied before YAG laser administration. The number of laser shots given per patient was at the discretion of the treating physician, but in all cases, laser application ceased after vaporization of the Weiss ring and all other visually significant floaters. Patients received only 1 laser treatment session to prevent unmasking of controls.

Participants in the sham group underwent similar treatment; they were fitted with a sham lens that had a lens filter glued to the surface to prevent YAG energy from passing through the lens. The YAG laser energy was at its lowest setting of 0.3 mJ. Patients were not asked to which group they believed they were randomized.

Postoperative Assessment

No topical therapy was given postoperatively. Intraocular pressure was measured at 30 minutes postoperatively. At postoperative week 1, month 1, and month 3, all patients underwent repeated assessment with non-BCVA slitlamp and indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression of study eye and applanation tonometry. At postoperative month 6, all patients completed the NEI VFQ-25 and a questionnaire to assess their floater symptoms with the following questions: (1) Rate your visual disturbance by floaters on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no symptoms and 10 indicating debilitating symptoms; (2) Quantify your postoperative improvement as a percentage; and (3) How would you describe your floaters today compared with right before the laser procedure ([a] floaters are worse, [b] floaters are the same, [c] some improvement but still floaters of moderate inconvenience, [d] significant improvement with floaters only of slight inconvenience, or [e] complete resolution of floaters)?

The ETDRS BCVA, color photography, optical coherence tomography, infrared photography, and slitlamp and indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression of the study eye and applanation tonometry were performed again at postoperative month 6. One of us (J.S.H.) graded the masked wide-angle photographs for the presence of floaters by using the same 5-level qualitative scale used by patients to self-report their postoperative symptoms compared with baseline. One of us (J.S.H.) used the following percentages to quantify the level of improvement: worse, less than 0%; same, 0%; partial success, 30% to 50%; significant success, 50% to 70%; and complete success, 100%.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous outcome variables were compared between treatment groups with a 2-sample t test and within treatment groups using a paired t test (Excel, Microsoft Corporation). The 5-level qualitative scale was analyzed as the proportion reporting significant or complete resolution using a 2-sample test of proportion (Stata version 12.1, StataCorp). P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Fifty-two patients (52 eyes; 17 men and 35 women; 51 white and 1 Asian) with symptomatic Weiss rings were enrolled; all were followed up for 6 months. The mean (SD) age of participants was 61.4 (8.0) years in the YAG group and 61.1 (6.6) years in the sham group (age range, 34-77 years; median age, 62 years). The 36 eyes treated with YAG laser vitreolysis (69% phakic) received a mean of 218 laser shots with a mean power of 1316 mJ. Mean duration of symptomatic floaters was 6.7 years (range, 0.5-63.0 years; median, 2.0 years) in the YAG group and 5.0 years (range, 0.5-30.0 years; median, 3 years) in the sham group.

Improvement

The YAG group reported significantly greater improvement in self-reported floater-related visual disturbance (54%) compared with sham controls (9%) (difference, 45%; 95% CI, 25%-64%; P < .001) (eFigure in Supplement 2). There was no appreciable learning curve effect with YAG vitreolysis; the first 10 patients reported similar improvements as the last 10 patients (54% vs 55%; P = .93).

Visual Disturbance Score on a 10-Point Scale

The YAG group had greater improvement in the visual disturbance score (improvement, 3.2) than did the sham group (improvement, 0.13) (difference, −3.0; 95% CI, −4.3 to −1.7; P < .001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Ten-Point Visual Disturbance Scores at Baseline vs 6 Months for the YAG and Sham Groups.

| Variable | YAG Group | Sham Group | Difference Between YAG and Sham Groups at 6 mo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 mo | Baseline | 6 mo | ||

| Mean (SD) [95% CI] | 6.4 (1.6) [5.9 to 6.9] | 3.3 (2.5) [2.5 to 4.0] | 6.4 (1.9) [5.5 to 7.3] | 6.3 (1.5) [5.4 to 7.1] | −3.0 [−4.3 to −1.7]a |

| Median (range) | 7.0 (4.0 to 10.0) | 3.0 (0 to 7.0) | 6.0 (4.0 to 10.0) | 7.0 (3.0 to 8.0) | NA |

| First quartile | 5.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 5.8 | NA |

| Second quartile | 7.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | NA |

| Third quartile | 7.3 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

P < .001.

Symptoms on a 5-Level Qualitative Scale

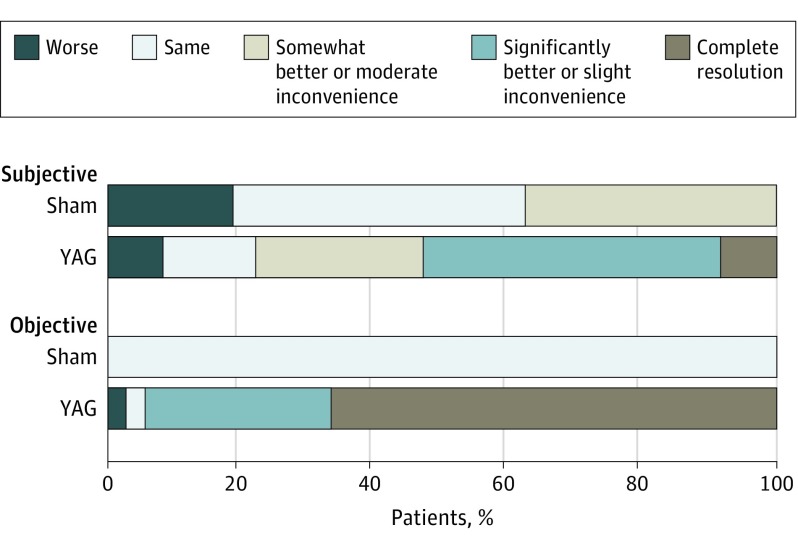

Figure 2 shows that 19 of 36 patients (53%) in the YAG group reported their symptoms as significantly or completely better after treatment vs 0 in the sham group (difference, 53%; 95% CI, 36%-69%; P < .001).

Figure 2. Subjective vs Objective Grading of Floater Resolution at 6 Months Using a 5-Level Qualitative Scale .

NEI VFQ-25 Scores

Table 2 shows that the YAG group reported significantly better general vision (69.4 vs 53.1; difference, 16.3; 95% CI, 0.9-31.7; P = .04) and peripheral vision (94.4 vs 82.8; difference, 11.6; 95% CI, 0.8-22.4; P = .04) and fewer role difficulties (93.1 vs 75.8; difference, 17.3; 95% CI, 8.0-26.6; P < .001) and dependency on others (98.8 vs 93.2; difference, 5.6; 95% CI, 0.4-10.8; P = .03) than did sham controls at 6 months.

Table 2. National Eye Institute Visual Functioning Questionnaire 25 Results at Baseline and 6 Months for the YAG and Sham Groups.

| Scale | YAG Group | Sham Group | Difference Between YAG and Sham Groups at 6 mo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 mo | P Value vs Baseline | Baseline | 6 mo | P Value vs Baseline | Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |

| General vision | 72.9 | 69.4 | .20 | 60.9 | 53.1 | .02 | 16.3 (0.9 to 31.7) | .04 |

| Ocular pain | 86.5 | 92.0 | .07 | 90.6 | 94.5 | .14 | −2.5 (−10.8 to 5.0) | .51 |

| Near vision | 80.9 | 86.8 | .02 | 75.8 | 80.5 | .23 | 6.3 (−4.0 to 16.7) | .22 |

| Far vision | 80.6 | 90.0 | <.001 | 82.3 | 83.3 | .70 | 6.7 (−1.4 to 14.8) | .10 |

| Color vision | 96.5 | 99.3 | .10 | 95.3 | 95.3 | >.99 | 4.0 (−10 to 9.0) | .11 |

| Peripheral vision | 88.9 | 94.4 | .04 | 89.1 | 82.8 | .48 | 11.6 (0.8 to 22.4) | .04 |

| General health | 72.2 | 69.4 | .32 | 71.9 | 64.1 | .02 | 5.4 (−8.8 to 19.6) | .45 |

| Mental health | 70.5 | 83.7 | .001 | 65.6 | 75.8 | .005 | 7.9 (−2.2 to 18.0) | .12 |

| Role difficulties | 81.6 | 93.1 | .002 | 74.2 | 75.8 | .68 | 17.3 (8.0 to 26.6) | <.001 |

| Dependency | 94.2 | 98.8 | .04 | 94.3 | 93.2 | .61 | 5.6 (0.4 to 10.8) | .03 |

| Driving | 75.5 | 79.4 | .29 | 79.2 | 76.6 | .73 | 2.8 (−14.5 to 20.2) | .74 |

Objective Change in Masked Grader Photographs

Figure 2 shows that 34 of 36 patients (94%) in the YAG group had significantly improved or completely resolved floaters compared with 0 in the sham group (difference, 94%; 95% CI, 87%-102%; P < .001). This objective 95% improvement was significantly greater than the subjective patient-reported improvement of 53% (P < .001).

ETDRS BCVA

Table 3 lists the visual acuity at baseline and 6 months for the YAG and sham groups. There was no change in ETDRS BCVA regardless of treatment group. In the YAG group, the visual acuity letter score was 81.7 (approximately 20/25) at baseline and 81.6 (approximately 20/25) at 6 months (P = .84). In the sham group, the visual acuity letter score was 81.9 (approximately 20/25) at baseline and 81.4 (approximately 20/25) at 6 months (P = .71). The BCVA changed by −0.2 letters in the YAG group and by −0.6 in the sham group (difference, 0.4; 95% CI, −6.5 to 5.3; P = .94).

Table 3. VA Letter Score at Baseline and 6 Months for the YAG and Sham Groups.

| Variable | VA (Approximate Snellen Equivalents) | Difference Between YAG and Sham at 6 mo |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YAG Group at Baseline |

Sham Group at Baseline |

YAG Group at 6 mo |

Sham Group at 6 mo |

||

| Mean (SD) [95% CI] | 81.7 (10.3 [78.4 to 85.1]) (20/25 [20/32-20/20]) | 81.9 (8.1 [78.0 to 85.9]) (20/25 [20/32-20/20]) | 81.6 (7.7) [79.0 to 84.2] (20/25 [20/25 to 20/20]) | 81.4 (7.8) [77.2 to 85.5] (20/25 [20/32 to 20/20]) | 0.18 (−4.47 to 4.83)a |

| Median (range) | 84 (31 to 95) (20/20 [20/250 to 20/12.5]) | 83.5 (58 to 95) (20/20 [20/63 to 20/12.5]) | 83.5 (50 to 90) (20/20 [20/100 to 20/16])b | 84 (66 to 92) (20/20 [20/50 to 20/16])c | NA |

| First quartile | 78 (20/25) | 80.5 (20/25) | 79 (20/25) | 77 (20/32) | NA |

| Second quartile | 84 (20/20) | 83.5 (20/20) | 83.5 (20/20) | 84 (20/20) | NA |

| Third quartile | 88 (20/16) | 86.25 (20/16) | 85.25 (20/20) | 86.25 (20/20) | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; VA, visual acuity.

P = .94.

P (paired) = .84.

P (paired) = .71.

Adverse Events

No retinal tears, retinal detachments, elevated intraocular pressure, or other significant adverse events occurred in the YAG group by postoperative month 6. One posterior chamber intraocular lens was pitted peripherally with the YAG laser when anterior floaters were treated, although this finding was not visually significant. A single retinal tear through lattice degeneration occurred in a patient in the sham group.

Discussion

The current study revealed moderate improvement in floater symptoms with a single laser session by postoperative month 6. Every subjective outcome measure in this study was aligned, supporting the efficacy of YAG vitreolysis. Patients typically believed that their floaters were 54% improved after a single treatment, with 53% of patients reporting significant or complete resolution of symptoms at postoperative month 6. Several measures of quality of life also improved compared with those in the sham laser group, including general vision and independence. The YAG group reported numerous improvements 6 months after treatment, including in near and distance activities and mental health.

These findings appear to show better efficacy than those reported in an analysis of 39 patients treated for PVD-related floaters by Delaney et al. They used a maximum pulse energy of 1.2 mJ with a mean power of 310.4 mJ per session. There were no complications after a mean of 1.62 treatment sessions and 26.6 months of follow-up. Only 38% of patients reported moderate or significant benefit from the treatment, defined as an improvement of at least 30% from baseline. The difference between the present study and the study by Delaney et al may relate to the mechanism by which YAG vitreolysis removes floaters. YAG works by vaporizing floaters caused by plasma formation, which may not be appreciated at the low power levels used by Delaney et al. At lower power levels, the vitreous is fractionated but not vaporized.

In the present study, patients in the sham group reported a 9% improvement in symptoms at 6 months (range, 0%-60%; median, 0%), and 5 of the 16 patients (31%) in the sham group reported between 20% and 60% improvement in their floater symptoms. This finding suggests a small placebo effect with YAG vitreolysis or possibly relates to the effect of time.

This study observed noticeable discrepancies between the masked grading of photographs by one of us (J.S.H.) and patients’ subjective responses. There are several possible explanations, including that the treating surgeon did not appropriately manage patient expectations; patients particularly disturbed by vitreous floaters may have high visual demands and thus have unrealistic visual expectations after YAG vitreolysis; and YAG vitreolysis may reduce the appearance of a Weiss ring on color photography, but patients remain bothered by other vitreous opacities not revealed by photography. To illustrate, of 8 patients who reported 0% improvement after YAG vitreolysis, one of us (J.S.H.) reported 100% improvement in 4 and 50% to 70% improvement in 3. Objectively identified worsening of floaters occurred in 1 case. This patient had a progressive floater duet (a Weiss ring plus fluffy anterior, inferior floaters) and was the only patient who underwent vitrectomy (no patients in the sham group underwent vitrectomy at a later date). The 7 other patients described small residual postoperative floaters. Although comparative photographs showed that their Weiss ring had improved after YAG treatment, these patients believed that the presence of residual floaters was just as bothersome as the original Weiss ring.

No adverse events judged to be of clinical relevance occurred after YAG laser vitreolysis in this small prospective study, which was underpowered to identify less common potential complications. However, with use of the rule of 3, there is 95% confidence that there is no greater than a 1 in 12 (8.3%) risk of a serious adverse event after YAG vitreolysis.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations, including its small sample size and short follow-up period. Larger studies with the same design are needed to corroborate the reported findings. Longer follow-up is required to determine the long-term stability of results and the degree of adverse events associated with the procedure. The current study focused on comparing YAG vitreolysis with sham but not with vitrectomy. Although such a comparison fell beyond the scope of this study, a future study comparing small-gauge vitrectomy with YAG vitreolysis would help illuminate the benefits and risks of each procedure. Similarly, although observation alongside patient education is the most common management approach for floaters, the current study did not include an observation arm to prevent unmasking patients in each treatment arm.

The current study also allowed just 1 treatment session per patient to prevent unmasking. However, this strategy may not reflect real-world treatment, in which patients may be treated with additional YAG vitreolysis sessions for persistent floaters after initial treatment. Furthermore, results from this study cannot be generalized to all patients with symptomatic floaters because only those with Weiss rings arising from PVD were treated.

Conclusions

For patients presenting with visual disturbance secondary to a clinically confirmed Weiss ring, the current study suggests that YAG vitreolysis improves short-term visual outcomes, both subjectively and objectively, without adverse events judged to be clinically relevant.

Trial Protocol

eFigure. Percentage of Postoperative Improvement in YAG Vitreolysis and Sham Groups at 6 Months

References

- 1.Sebag J, Yee K. Vitreous—from biochemistry to clinical relevance In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, eds. Duane’s Foundation of Clinical Ophthalmology. Vol 1 Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998:1-34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Nie KF, Crama N, Tilanus MA, Klevering BJ, Boon CJ. Pars plana vitrectomy for disturbing primary vitreous floaters: clinical outcome and patient satisfaction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(5):1373-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz-Key S, Carlsson JO, Crafoord S. Longterm follow-up of pars plana vitrectomy for vitreous floaters: complications, outcomes and patient satisfaction. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(2):159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Favre M, Goldmann H. Genesis of posterior vitreus body detachment [in French]. Ophthalmologica. 1956;132(2):87-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foos RY. Posterior vitreous detachment. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1972;76(2):480-497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delaney YM, Oyinloye A, Benjamin L. Nd:YAG vitreolysis and pars plana vitrectomy: surgical treatment for vitreous floaters. Eye (Lond). 2002;16(1):21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamou J, Wa CA, Yee KM, et al. . Ultrasound-based quantification of vitreous floaters correlates with contrast sensitivity and quality of life. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(3):1611-1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia GA, Khoshnevis M, Yee KM, Nguyen-Cuu J, Nguyen JH, Sebag J. Degradation of contrast sensitivity function following posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;172(9):7-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelkawi SA, Abdel-Salam AM, Ghoniem DF, Ghaly SK. Vitreous humor rheology after Nd:YAG laser photo disruption. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;68(2):267-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toczołowski J, Katski W. [Use of Nd:YAG laser in treatment of vitreous floaters]. Klin Oczna. 1998;100(3):155-157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai WF, Chen YC, Su CY. Treatment of vitreous floaters with neodymium YAG laser. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77(8):485-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karickhoff JR. Laser Treatment of Eye Floaters. Falls Church, VA: Washington Medical Publishing LLC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh P. YAG Laser Vitreolysis. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery; September 14, 2014; London, England. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure. Percentage of Postoperative Improvement in YAG Vitreolysis and Sham Groups at 6 Months