Key Points

Question

Do gender disparities in industry financial relationships between academic and industry otolaryngologists exist?

Findings

Using a comprehensive database of all full-time academic otolaryngologist that included bibliometric data and industry contributions from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payment Database, we found that male otolaryngologists received greater median contributions than did female otolaryngologists. Overall, a greater proportion of men received industry contributions than women (68.0% vs. 56.1%), and by subspecialty, men had greater median contribution levels among otologists, laryngologists, and rhinologists.

Meaning

A greater proportion of male than female academic otolaryngologists receive contributions from industry, suggesting that gender disparities may exist.

This study evaluates the existence of gender disparities in industry relationships with academic otolaryngologists.

Abstract

Importance

Gender disparities continue to exist in the medical profession, including potential disparities in industry-supported financial contributions. Although there are potential drawbacks to industry relationships, such industry ties have the potential to promote scholarly discourse and increase understanding and accessibility of novel technologies and drugs.

Objectives

To evaluate whether gender disparities exist in relationships between pharmaceutical and/or medical device industries and academic otolaryngologists.

Design, Setting, and Participants

An analysis of bibliometric data and industry funding of academic otolaryngologists.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Industry payments as reported within the CMS Open Payment Database.

Methods

Online faculty listings were used to determine academic rank, fellowship training, and gender of full-time faculty otolaryngologists in the 100 civilian training programs in the United States. Industry contributions to these individuals were evaluated using the CMS Open Payment Database, which was created by the Physician Payments Sunshine Act in response to increasing public and regulatory interest in industry relationships and aimed to increase the transparency of such relationships. The Scopus database was used to determine bibliometric indices and publication experience (in years) for all academic otolaryngologists.

Results

Of 1514 academic otolaryngologists included in this analysis, 1202 (79.4%) were men and 312 (20.6%) were women. In 2014, industry contributed a total of $4.9 million to academic otolaryngologists. $4.3 million (88.5%) of that went to men, in a population in which 79.4% are male. Male otolaryngologists received greater median contributions than did female otolaryngologists (median [interquartile range (IQR)], $211 [$86-$1245] vs $133 [$51-$316]). Median contributions were greater to men than women at assistant and associate professor academic ranks (median [IQR], $168 [$77-$492] vs $114 [$55-$290] and $240 [$87-$1314] vs $166 [$58-$328], respectively). Overall, a greater proportion of men received industry contributions than women (68.0% vs 56.1%,). By subspecialty, men had greater median contribution levels among otologists and rhinologists (median [IQR], $609 [$166-$6015] vs $153 [$56-$336] and $1134 [$286-$5276] vs $425 [$188-$721], respectively).

Conclusions and Relevance

A greater proportion of male vs female academic otolaryngologists receive contributions from industry. These differences persist after controlling for academic rank and experience. The gender disparities we have identified may be owing to men publishing earlier in their careers, with women often surpassing men later in their academic lives, or as a result of previously described gender disparities in scholarly impact and academic advancement.

Introduction

The Open Payments Program of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently introduced mandatory online reporting of payments to physicians from the pharmaceutical and medical technology industries, with initial public reporting encompassing 2014. These reporting requirements, established by the Physician Payments Sunshine Act, resulted from increasing public/regulatory interest in industry relationships. The movement toward increasing the transparency of physician-industry relationships was propelled by studies such as 1 demonstrating that more than 80% of physicians received contributions worth monetary value from industry. Another analysis of industry ties and comparison among various surgical specialties noted that otolaryngologists had fewer financial relationships with industry compared with surgeons practicing in other specialties.

Although there have been several analyses examining financial industry ties among physicians practicing various specialties, to our knowledge none have focused on the impact of gender. Despite an increasing number of female residents in training, the field of otolaryngology, and particularly senior academic otolaryngology, remains male-dominated, much like other surgical specialties. Numerous studies have examined and noted gender disparities in self-perception, financial compensation, academic advancement, and scholarly impact between genders in otolaryngology. Although there are potential downsides to close industry relationships, including concerns that they may potentiate influence on clinical and research practices, industry collaboration also has the potential to promote scholarly discourse and increase understanding and accessibility of novel technologies and drugs. Our objective was to evaluate whether gender disparities exist in industry relationships with academic otolaryngologists.

Methods

The American Medical Association’s Fellowship and Residency Interactive Database (FREIDA) was accessed for a list of US allopathic otolaryngology residency programs. After exclusion of military programs, the online websites of the 100 civilian training programs were searched to construct a comprehensive database of all current, full-time otolaryngology faculty. The following information was recorded from each site: faculty names, fellowship training, and academic rank. In addition, the names and online pictures of each faculty member were used by the authors to classify each individual’s gender.

Industry contributions during 2014 for each faculty member identified were determined using the CMS Open Payment Database. Names were directly inputted into this search engine, and results returned contained information regarding practice location and physician specialty, helping confirm that the appropriate individuals were queried. “General payments” (payments not directly related to research, including contributions for educational purposes, honoraria/speaking fees, consulting fees, food and beverage expenses), as well as research payments and/or associated research funding, categorized hereafter as “industry contributions,” were recorded from this site.

In addition to the above information, the Scopus database (http://www.scopus.com) was used to determine scholarly impact, as measured by the h-index, total number of publications, and publication range. Publication range, defined in years as the date from an individual’s first publication, can be used as a proxy measure for experience in academic medicine. The h-index is an easily calculable, objective, and widely available bibliometric that measures the consistency with which an individual is being cited throughout their body of work; it has been shown to be strongly associated with scholarly success, academic promotion, extramural funding, and fellowship training in otolaryngology. Data collection was completed in December 2015.

Statistical Analysis

Nonparametric descriptive statistics were reported because industry payments did not conform to a normal distribution. Effect size for absolute difference in medians was calculated as described by Rosenthal. In addition, 25th and 75th quartiles are given for all reported median values. Effect size was calculated using Cohen d statistic and Cohen h statistic where appropriate. Effect sizes of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 are interpreted as small, medium, and large, respectively. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS statistical software (version 24, IBM).

Ethical Considerations

The CMS Open Payments Database, Scopus Database, and individual departmental websites are all publicly available and qualify as nonhuman subject research. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

Results

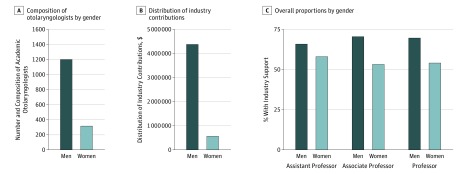

Of 1514 academic otolaryngologists included in this analysis, 1202 (79.4%) were men and 312 (20.6%) were women (Figure 1A). In 2014, industry contributed a total of $4 945 631 to the 1514 academic otolaryngologists included. Of this amount, $4 378 605 (88.5%) involved funding to men and $567 026 (11.5%) to women (Figure 1B). Of individuals with industry relationships, men received slightly higher median industry contributions (median [interquartile range (IQR)], $211 [$86-$1245]) than women (median [IQR], $133 [$51-$316]) (Table 1).

Figure 1. Gender Distribution of Industry Contributions Among Academic Otolaryngologists.

A, Gender composition of otolaryngologists. B, Distribution of industry contributions. C, Overall proportion of men and women receiving industry contributions organized by academic rank. The dark bars represent men, light bars represent women.

Table 1. Median Industry Contribution Levels Organized by Gender for 1202 Men and 312 Women.

| Academic Rank | Median (IQR) | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men, $ | Women, $ | ||

| Overall | 211 (86-1245) | 133 (51-316) | 0.14 |

| Assistant professor | 168 (77-492) | 115 (55-290) | 0.10 |

| Associate professor | 241 (88-1314) | 166 (58-328) | 0.19 |

| Professor | 363 (143-157 734) | 153 (50-8 887) | 0.11 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

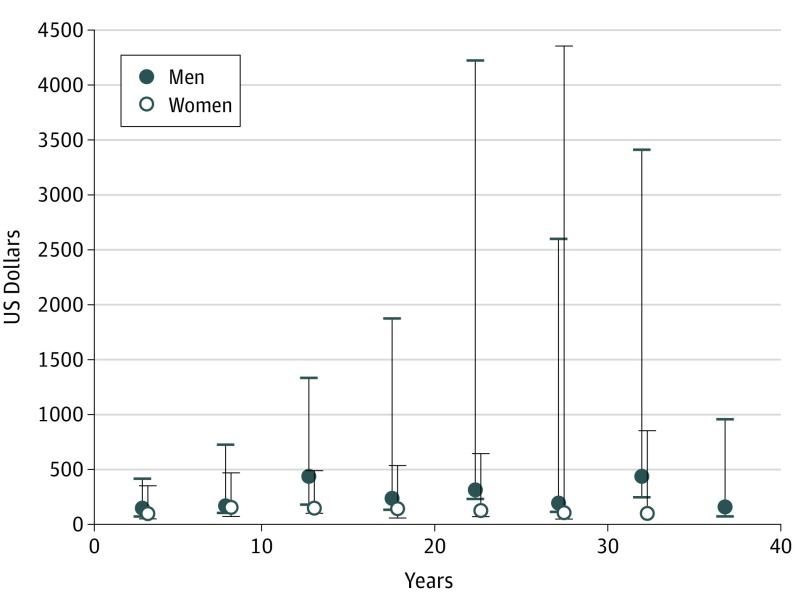

When controlling for academic rank, men received higher median industry contributions (including general payments, research payments, and associated research payments), however the observed effect size was very small (Table 1). Of the 1514 academic otolaryngologists, 992 received industry contributions (817 men and 175 women). Overall, this means a greater proportion of men received industry contributions (68.0% vs 56.1%) (Figure 1C and D), which translates to $5359 per man and $3240 per woman who did receive industry contributions. Although there were not large differences between genders in whether or not assistant professors received industry contributions, there were clear differences at the higher levels. A greater proportion of men than women received industry contributions at the level of associate professor and professor (Figure 1E). When gauged by academic experience (ie, publication range), men and women demonstrated different contribution curves, with considerable differences noted beyond 10 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Median Industry Contributions by Academic Experience in Years.

As measured by publication range. Filled circles represent men, open circles represent women. Error bars represent interquartile range. Five-year averages (medians) were used.

A greater proportion of men received industry research payments and industry-associated funding compared with women (5.2% vs 1.9%) (Table 2). In 2014, out of $2 229 097 of research payments and/or funding, 83.1% went to men. Between men and women receiving research payments and/or funding, there was noticeable differences in scholarly impact, as measured by the h-index (21.5 [standard error of mean, 0.39] vs 16.5 [standard error of mean, 0.46]), as well as publications (97.1 publications vs 55.5 publications) (Table 2). Of the top 10% of males and females based on h-index, 65.5% of men vs only 28.1% of women received industry funding. However, of this academically productive group, 9.2% and 9.4% of men and women received research payments, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of Academic Otolaryngologists Receiving Research Funding and/or Payments.

| Variable | Men (n = 1202) | Women (n = 312) | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| With industry contributions, (%) | 68.1 (65.5) | 56.1 (28.1) | 0.25 (0.77) |

| With research payments/funding, (%) | 5.2 (9.2) | 1.9 (9.4) | 0.18 (0.01) |

| Total research payments and/or funding, $a | 1 852 599 (723 010) | 376 498 (227 497) | |

| Mean research payments and/or funding, $a | 30 370.5 (6075.7) | 62 749.7 (7109.3) | 0.54 (0.03) |

| Mean h-index [SEM]a | 21.5 [0.3] (38.0 [0.96]) | 16.5 [0.46] (25.5 [1.51]) | 0.46 (1.11) |

| Mean publications [SEM]a | 97.1 [2.5] (52.1 [2.17]) | 55.5 [2.4] (21.3 [1.93]) | 0.69 (0.89) |

Abbreviation: SEM, standard error of mean.

Values in parentheses denote characteristics of top 10% of academic otolaryngologists based on h-index.

The proportion of men and women receiving industry contributions organized by otolaryngologic subspecialty is detailed in Table 3. When considering median industry contributions by subspecialty, several small gender differences were noted (Table 3). Specifically, men who received industry contributions had significantly higher median support levels than women among otologists/neurotologists, laryngologists, and rhinologists/anterior skull base surgeons. Men received a greater proportion of total funding than would be expected by gender composition among all subspecialties with fellowship training; in contrast, only 63.9% of industry contributions among non–fellowship-trained otolaryngologists went to men, lower than would be expected because 79.3% of non–fellowship-trained academic otolaryngologists in this analysis were men (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Proportion and Amounts of 1202 Men and 312 Women Receiving Industry Contributions Organized by Fellowship.

| Fellowship Type | Men (IQR) | Women (IQR) | Effect Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | $a | % | $a | ||

| Non–fellowship trained | 64.8 | 161 (59-695) | 61.1 | 101 (59-313) | 0.06 |

| Head and neck surgery | 65.2 | 173 (83-543) | 60.8 | 162 (93-382) | 0.04 |

| Otology/neurotology | 74.6 | 609 (166-6015) | 58.6 | 153 (56-336) | 0.21 |

| Laryngology | 71.4 | 106 (25-904) | 43.8 | 121 (24-212) | 0.24 |

| Rhinology/anterior skull base | 85.3 | 1133 (285-5276) | 68.4 | 425 (188-721) | 0.28 |

| Facial plastic and reconstructive | 78.1 | 177 (92-431) | 72.0 | 156 (74-288) | 0.07 |

| Pediatric otolaryngology | 52.7 | 119 (51-279) | 45.5 | 95 (40-182) | 0.09 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Average dollar amounts represent median funding per individuals receiving funding.

Discussion

There are gender disparities in medicine, including among academic physicians. Although women have been historically underrepresented in the medical profession, the gender gap in medical school enrollment has been eliminated in recent decades. Nevertheless, many surgical specialties including otolaryngology have had difficulty attracting women; the situation is improving but still exists. Our group has previously reported considerable gender differences in several factors, including scholarly impact and grants awarded from the National Institutes of Health among academic otolaryngologists, suggesting that these disparities may be partly responsible for the underrepresentation of women in departmental leadership structures. These differences have been noted in other specialties as well.

Our recent analysis evaluating industry financial ties among academic otolaryngologists noted that receiving industry contributions greater than $1000 is associated with greater scholarly impact. That study design, like this one, did not allow for attribution of causality. Industry representatives frequently target key opinion leaders (KOLs) with the intent to create and impact scholarly discourse. A previous study of scholarly productivity in otolaryngology showed that men publish earlier in their careers; women lag behind early but then catch up and often surpass men later on in their academic lives. This may explain why women may not be viewed as KOLs early in their careers and thus not attract funding by industry. Our analysis shows a relative equality of those who received research funding and total research dollars given by industry between men and women who are among the top 10% for their gender based on scholarly productivity. However, scholarly productivity may only contribute in part to academic and industry impact, and thus an individual’s role as a KOL. The data show that assistant professors, who are not KOLs and have the smallest numbers of publications, are funded equivalently by gender while among associate and full professors, representing KOLs with large numbers of publications, women are funded less frequently and for less money when they are funded. Our analysis showed that the slight disparity in female industry funding which did not diminish over the years, in contrast to previous analyses indicating women have scholarly productivity curves equaling and surpassing those of men later in their careers, is a finding worthy of closer examination. Potential reasons include lack of mentoring for women on how to approach and/or respond to industry and how to negotiate for appropriate funding, as well as the paucity of women on panels or as invited speakers at national and international meetings, thereby diminishing their ability to establish themselves as KOLs. These factors have generally been identified as barriers to advancement for women in academic medicine.

Men received both more instances of industry contributions and more money than women, among otologists/neurotologists, laryngologists, and rhinologists. The subspecialties of otology/neurotology and rhinology were particularly skewed for considerably higher median industry contributions for men, and were the 2 groups with the greatest proportion of practitioners receiving considerable industry contributions (defined as support >$1000) in the previous analysis. Notably, these fields are 2 of the 3 most male-dominated subspecialties in otolaryngology.

In addition, we speculate that men and women may harbor differing opinions and behaviors with respect to seeking and accepting industry funding. It is plausible that some women choose not to pursue industry funding. Perhaps as women become more academically productive later in their careers and thus more likely to be targeted as KOL, they find less motivation to pursue such industry ties. However, investigation of this behavior is beyond the scope of this study. Further, the metrics used in the context of gender disparities here paint a favorable picture for industry contributions. We feel that it is important to keep in mind the various negative aspects of industry contributions in health care, and how awareness of such ties may influence any number of sub-groups among otolaryngology, including women.

To our knowledge, this is the first published analysis focusing on gender-based patterns in physician-industry relationships. We demonstrated several associations, but can only speculate on the causalities and/or ramifications. These disparities may be a result of other gender disparities. The different trajectories between women and men in scholarly impact and academic advancement may in turn influence who is identified as a KOL by industry. Advocates of strengthening industry ties with health care note that such relationships, involving both research and nonresearch contributions, may play an important role in increasing access to novel technologies and furthering scholarly discourse. This may take on special importance in a smaller field, such as otolaryngology, in which the impact of scholarly activities may be limited relative to other fields and seeking alternate sources of support may be 1 way of increasing impact. Opponents of industry relationships cite prior instances of inappropriate industry influence on clinical practice patterns and research. Establishing a balance with appropriate oversight and transparency may be an important step, and robust conflict of interest disclosure requirements as well as disseminating industry associations as achieved by the Sunshine Act are important steps that have been taken in recent years. A secondary, possibly unanticipated consequence of the Sunshine Act may be that gender and other disparities in industry contributions can now be more easily identified and addressed.

Limitations

Although this is the first analysis to evaluate gender differences in physician-industry relationships among otolaryngologists, we would be remiss not to comment on several limitations. Importantly, we are not able to conclude why these differences were noted, although we are able to speculate on possible reasons. The Sunshine Act data has only been available since 2014. As recently as 1998, only 6% of otolaryngologists were women, and this number has risen above 20% within the past decade. It would be of interest to reevaluate industry relationships as more years of information become available through this resource and as greater numbers of women advance in academic seniority to see how a higher number of female KOLs impacts the differences we noted. In addition, despite the strengths of multivariable regression analysis, we feel that simultaneously controlling for multiple variables (gender, fellowship training, academic rank, and productivity/experience) in such a small cohort, such as female academic otolaryngologists receiving industry support, is not entirely appropriate. The overwhelming underrepresentation of women in otolaryngology is demonstrated both in prior analyses as well as among the cohort we collected in this analysis. Hence, women already represent a small portion of the faculty included in this analysis, and controlling for many different factors at once in a multivariable regression analysis eliminates the ability to detect statistical differences. Also, there are potential sources of variability inherent to our data collection. An accurate, comprehensive database relies on currently updated academic departmental websites. In addition, each department may employ different methodologies for including and reporting full-time, part-time, adjunct, or affiliate faculty. Furthermore, there is a potential for lack of consistency in reporting of fellowship training or subspecialty expertise on academic websites, and relying on names and photos for gender identification leaves room for error. Despite these limitations in data acquisition from departmental websites, we still feel this is the most robust method for analysis of population characteristics available, and does not suffer from recall and reporting biases that are often found with other methodologies used to answer such questions.

Conclusions

Among academic otolaryngologists, a greater proportion of men have financial ties with industry, differences which persist after controlling for academic rank and experience. Among otologists/neurotologists, laryngologists, and rhinologists, women receive a smaller proportion of industry contributions than would otherwise be expected by the gender composition of each subspecialty. As industry seeks KOLs for collaboration, and a recent study has reported an association between considerable industry contributions and increased scholarly impact, the gender disparities we report may be a result of previously described gender differences in scholarly impact and academic advancement, although this is speculative and beyond the scope of this analysis. As more data are made available and as women advance in academic otolaryngology, further analyses will likely help answer some of these questions.

eFigure. Gender-specific Trends in Industry Contributions Organized by Fellowship Training

References

- 1.Agrawal S, Brennan N, Budetti P. The Sunshine Act—effects on physicians. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2054-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang JS. The Physician Payments Sunshine Act: data evaluation regarding payments to ophthalmologists. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(4):656-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iyer S, Derman P, Sandhu HS. Orthopaedics and the Physician Payments Sunshine Act: an examination of payments to U.S. orthopaedic surgeons in the Open Payments Database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(5):e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samuel AM, Webb ML, Lukasiewicz AM, et al. orthopaedic surgeons receive the most industry payments to physicians but large disparities are seen in Sunshine Act Data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(10):3297-3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, Miller LG, Cleary PD, Blumenthal D. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1742-1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rathi VK, Samuel AM, Mehra S. Industry ties in otolaryngology: initial insights from the physician payment sunshine act. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(6):993-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cvetanovich GL, Chalmers PN, Bach BR Jr. Industry financial relationships in orthopaedic surgery: analysis of the Sunshine Act Open Payments Database and comparison with other surgical subspecialties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(15):1288-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey HB, Alkasab TK, Pandharipande PV, et al. Non-research-related physician-industry relationships of radiologists in the United States. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(11):1142-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalowitz DI, Spillman MA, Morgan MA. Interactions with industry under the Sunshine Act: an example from gynecologic oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):703-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson BJ, Grandis JR. Women in otolaryngology: closing the gender gap. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14(3):159-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blakemore LC, Hall JM, Biermann JS. Women in surgical residency training programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(12):2477-2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benzil DL, Abosch A, Germano I, et al. ; WINS White Paper Committee . The future of neurosurgery: a white paper on the recruitment and retention of women in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(3):378-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis EC, Risucci DA, Blair PG, Sachdeva AK. Women in surgery residency programs: evolving trends from a national perspective. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(3):320-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eloy JA, Svider PF, Cherla DV, et al. Gender disparities in research productivity among 9952 academic physicians. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(8):1865-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wynn R, Rosenfeld RM, Lucente FE. Satisfaction and gender issues in otolaryngology residency. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(6):823-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandis JR, Gooding WE, Zamboni BA, et al. The gender gap in a surgical subspecialty: analysis of career and lifestyle factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(6):695-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eloy JA, Blake DM, D’Aguillo C, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, Baredes S. Academic benchmarks for otolaryngology leaders. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(8):622-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eloy JA, Svider P, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. Gender disparities in scholarly productivity within academic otolaryngology departments. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(2):215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eloy JA, Svider PF, Kovalerchik O, Baredes S, Kalyoussef E, Chandrasekhar SS. Gender differences in successful NIH grant funding in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(1):77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeAngelis CD, Fontanarosa PB. Impugning the integrity of medical science: the adverse effects of industry influence. JAMA. 2008;299(15):1833-1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fugh-Berman A, Ahari S. Following the script: how drug reps make friends and influence doctors. PLoS Med. 2007;4(4):e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sismondo S. Key opinion leaders and the corruption of medical knowledge: what the Sunshine Act will and won’t cast light on. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41(3):635-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eloy JA, Svider PF, Kanumuri VV, Folbe AJ, Setzen M, Baredes S. Do AAO-HNSF CORE grants predict future NIH funding success? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(2):246-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eloy JA, Svider PF, Mauro KM, Setzen M, Baredes S. Impact of fellowship training on research productivity in academic otolaryngology. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(12):2690-2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eloy JA, Svider PF, Setzen M, Baredes S, Folbe AJ. Does receiving an American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation Centralized Otolaryngology Research Efforts grant influence career path and scholarly impact among fellowship-trained rhinologists? Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4(1):85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svider PF, Blake DM, Setzen M, Folbe AJ, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Rhinology fellowship training and its scholarly impact. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27(5):e131-e134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svider PF, Choudhry ZA, Choudhry OJ, Baredes S, Liu JK, Eloy JA. The use of the h-index in academic otolaryngology. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(1):103-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svider PF, Mady LJ, Husain Q, et al. Geographic differences in academic promotion practices, fellowship training, and scholarly impact. Am J Otolaryngol. 2013;34(5):464-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svider PF, Mauro KM, Sanghvi S, Setzen M, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Is NIH funding predictive of greater research productivity and impact among academic otolaryngologists? Laryngoscope. 2013;123(1):118-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svider PF, Pashkova AA, Choudhry Z, et al. Comparison of scholarly impact among surgical specialties: an examination of 2429 academic surgeons. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(4):884-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenthal R; SAGE Research Methods Online Meta-analytic procedures for social research Applied social research methods series v 6. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 1991:x, 155 p. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Association of American Medical Colleges Women in US Academic Medicine: Statistics and Benchmarking Report 2009-2010. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Accessed November 5, 2016.

- 33.Serrano K. Women residents, women physicians and medicine’s future. WMJ. 2007;106(5):260-265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borman KR. Gender issues in surgical training: from minority to mainstream. Am Surg. 2007;73(2):161-165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eloy JA, Mady LJ, Svider PF, et al. Regional differences in gender promotion and scholarly productivity in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(3):371-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill EK, Blake RA, Emerson JB, et al. Gender differences in scholarly productivity within academic gynecologic oncology departments. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(6):1279-1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holliday EB, Jagsi R, Wilson LD, Choi M, Thomas CR Jr, Fuller CD. Gender differences in publication productivity, academic position, career duration, and funding among U.S. academic radiation oncology faculty. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):767-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez SA, Svider PF, Misra P, Bhagat N, Langer PD, Eloy JA. Gender differences in promotion and scholarly impact: an analysis of 1460 academic ophthalmologists. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):851-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez M, Lopez S, Beebe K. Gender comparison of scholarly production in the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society using the Hirsch Index. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1172-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Svider PF, D’Aguillo CM, White PE, et al. Gender differences in successful National Institutes of Health funding in ophthalmology. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(5):680-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomei KL, Nahass MM, Husain Q, et al. A gender-based comparison of academic rank and scholarly productivity in academic neurological surgery. J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21(7):1102-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svider PF, Bobian M, Lin HS, et al. Are industry financial ties associated with greater scholarly impact among academic otolaryngologists? Laryngoscope. 2017;127(1):87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jenkins NR. Variation in the h-Index and its use in the assessment of academic output. World Neurosurg. 2016;87:619-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reed DA, Enders F, Lindor R, McClees M, Lindor KD. Gender differences in academic productivity and leadership appointments of physicians throughout academic careers. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Folbe AJ, Svider PF, Setzen M, Zuliani G, Lin HS, Eloy JA. Scientific inquiry into rhinosinusitis: who is receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health? Laryngoscope. 2014;124(6):1301-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eloy JA, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, Setzen M, Baredes S. AAO-HNSF CORE grant acquisition is associated with greater scholarly impact. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(1):53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery/Foundation Inc 2011. Code for Interactions with Companies. https://www.entnet.org/sites/default/files/Code%20for%20Interactions%20with%20Companies_approved%2010sept11_0.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- 48.Berk RA. Regression Analysis A Constructive Critique Advanced Quantitative Techniques in the Social Sciences Ser 11. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Gender-specific Trends in Industry Contributions Organized by Fellowship Training