Key Points

Question

How does physician reimbursement in Medicare Advantage compare with traditional Medicare’s rates and commercial health insurance rates?

Findings

In this analysis of 144 million claims for common services from 2007 to 2012, physician reimbursement in Medicare Advantage was more strongly tied to traditional Medicare rates than to negotiated commercial prices, although Medicare Advantage plans tended to pay physicians less than traditional Medicare. However, Medicare Advantage plans take advantage of the commercial market’s favorable pricing for services for which traditional Medicare overpays, including laboratory tests and durable medical equipment.

Meaning

Traditional Medicare’s administratively set rates act as an anchor for physician reimbursement in the Medicare Advantage market. Reforms that would transition the Medicare program toward premium support models that end traditional Medicare could affect how clinicians are paid.

This analysis of claims data compares physician reimbursement in Medicare Advantage, traditional Medicare, and commercial health insurance plans.

Abstract

Importance

Nearly one-third of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in a Medicare Advantage (MA) plan, yet little is known about the prices that MA plans pay for physician services. Medicare Advantage insurers typically also sell commercial plans, and the extent to which MA physician reimbursement reflects traditional Medicare (TM) rates vs negotiated commercial prices is unclear.

Objective

To compare prices paid for physician and other health care services in MA, traditional Medicare, and commercial plans.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective analysis of claims data evaluating MA prices paid to physicians and for laboratory services and durable medical equipment between 2007 and 2012 in 348 US core-based statistical areas. The study population included all MA and commercial enrollees with a large national health insurer operating in both markets, as well as a 20% sample of TM beneficiaries.

Exposures

Enrollment in an MA plan.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Mean reimbursement paid to physicians, laboratories, and durable medical equipment suppliers for MA and commercial enrollees relative to TM rates for 11 Healthcare Common Procedure Coding Systems (HCPCS) codes spanning 7 sites of care.

Results

The sample consisted of 144 million claims. Physician reimbursement in MA was more strongly tied to TM rates than commercial prices, although MA plans tended to pay physicians less than TM. For a mid-level office visit with an established patient (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] code 99213), the mean MA price was 96.9% (95% CI, 96.7%-97.2%) of TM. Across the common physician services we evaluated, mean MA reimbursement ranged from 91.3% of TM for cataract removal in an ambulatory surgery center (CPT 66984; 95% CI, 90.7%-91.9%) to 102.3% of TM for complex evaluation and management of a patient in the emergency department (CPT 99285; 95% CI, 102.1%-102.6%). However, for laboratory services and durable medical equipment, where commercial prices are lower than TM rates, MA plans take advantage of these lower commercial prices, ranging from 67.4% for a walker (HCPCS code E0143; 95% CI, 66.3%-68.5%) to 75.8% for a complete blood cell count (CPT 85025; 95% CI, 75.0%-76.6%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Traditional Medicare’s administratively set rates act as a strong anchor for physician reimbursement in the MA market, although MA plans succeed in negotiating lower prices for other health care services for which TM overpays. Reforms that transition the Medicare program toward some premium support models could substantially affect how physicians and other clinicians are paid.

Introduction

There is considerable variation in the negotiated prices that private health insurers pay to clinicians for treating commercially insured patients in the United States. Unlike commercial payers, Medicare reimburses physicians and other clinicians according to an administratively set fee schedule. However, nearly one-third of Medicare beneficiaries are covered by private insurers through the Medicare Advantage (MA) program, and less is known about how these private MA plans reimburse clinicians. On the one hand, we may expect clinician reimbursement in MA to be similar to traditional Medicare’s administratively set rates because the amount that the federal government pays MA plans to provide insurance coverage for MA enrollees is largely based on local traditional Medicare spending levels. However, these same insurers negotiate prices with clinicians for their commercial enrollees that differ from traditional Medicare and reflect market forces, so it is possible that these same market dynamics could affect the MA market. In addition to understanding how clinicians are being paid for care of a large and growing share of Medicare beneficiaries, empirical evidence on clinician reimbursement in MA is also important for evaluating the potential impact of proposed Medicare reforms that would transition Medicare to be increasingly reliant on private plans, including the impact that such reforms might have on clinician payment.

Several recent studies have shown that MA plans pay hospitals at rates that are similar to or slightly less than those of traditional Medicare; however, there is little empirical evidence outside the hospital setting. We present data on MA reimbursement for physician services, laboratory tests, and durable medical equipment from a retrospective analysis of claims data from 2007 through 2012.

Methods

Data Sources

We analyzed claims data for MA and commercial enrollees from a large national insurer operating in both markets from 2007 through 2012. In 2012, the insurer held 17% of nationwide MA market share and offered 1 or more MA plans in 98% of counties, in which 94% of Medicare beneficiaries lived. The data include the full set of adjudicated and paid claims for all enrollees; enrollment increased from 1.7 million in 2007 to 2.6 million in 2012.

We measured traditional Medicare rates from a 20% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries through a data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The study was considered exempt by the institutional review board of the University of Southern California. Data were deidentified.

Sample and Procedure Selection

We restricted our analysis to patients enrolled for the entire calendar year, either with the private insurer in the MA and commercial plans or in traditional Medicare. We restricted our sample to those enrolled in managed care plans by excluding enrollment in the private insurer’s indemnity and private fee-for-service (MA) plans. We selected a subset of procedures (identified by the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes) that represented high total expenditures and/or claim volume and spanned different types of clinicians and health care services (eg, primary care physicians, specialist physicians, laboratory services) and multiple places of service (eg, physician’s office, hospital inpatient and outpatient, ambulatory surgery center [ASC], independent laboratories). Additional detail on the selected procedures is provided in the Table. While we examined a wide range of services in our analysis, for brevity we present results for these 11 procedure codes spanning 7 sites of care. However, the results are substantively unchanged when a broader set of services is examined.

Table. Selected Procedures, Number of Claims and Markets, Mean Traditional Medicare Reimbursement, and Within-Market Variationa.

| Procedure and Place of Service | Claims, No. | CBSAs, No. | TM Price, Mean (SD), $ | Interquartile Price Variation Within CBSAs, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM | MA | Commercial | ||||

| 99213 - Office visit (moderate) | ||||||

| Office | 76 420 657 | 348 | 61.54 (5.07) | 2.1 | 8.2 | 27.0 |

| 99232 - Hospital care (moderate) | ||||||

| Inpatient | 26 314 942 | 300 | 66.16 (3.33) | 1.3 | 9.6 | 31.7 |

| 27447 - Total knee arthroplasty | ||||||

| Inpatient | 118 465 | 156 | 1461.74 (92.30) | 2.5 | 6.7 | 30.5 |

| 66984 - Cataract removal | ||||||

| Outpatient | 174 353 | 168 | 669.05 (59.41) | 2.0 | 8.3 | 45.5 |

| Ambulatory surgery center | 335 783 | 182 | 670.28 (62.20) | 2.1 | 9.1 | 26.3 |

| 45385 - Colonoscopy | ||||||

| Outpatient | 151 028 | 167 | 294.42 (18.44) | 1.8 | 7.1 | 39.9 |

| Ambulatory surgery center | 147 885 | 120 | 300.55 (21.45) | 2.4 | 11.4 | 31.9 |

| 70450(26)- CT head/neck (interpretation) | ||||||

| Inpatient | 906 690 | 229 | 42.08 (1.96) | 1.6 | 3.2 | 79.6 |

| Emergency department | 1 307 386 | 263 | 41.85 (1.83) | 1.2 | 5.9 | 72.5 |

| 99285 - Emergency visit (complex) | ||||||

| Emergency department | 5 756 942 | 302 | 167.21 (7.46) | 1.8 | 5.3 | 179.9 |

| 85025 - Complete blood cell count | ||||||

| Office | 10 351 313 | 277 | 10.97 (0.33) | 0 | 9.5 | 37.3 |

| Laboratory | 13 107 139 | 202 | 10.82 (0.60) | 0 | 12.1 | 10.3 |

| A7030 - Face mask for CPAP | ||||||

| Patient’s home | 349 738 | 213 | 177.08 (8.72) | 0 | 17.4 | 8.6 |

| E0143 - Walker | ||||||

| Patient’s home | 458 023 | 224 | 107.31 (10.17) | 1.9 | 20.9 | 13.2 |

| E1390 - Oxygen concentrator | ||||||

| Patient’s home | 8 294 423 | 271 | 181.72 (13.39) | 0.1 | 17.8 | 11.0 |

Abbreviations: CBSA, core-based statistical area; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CT, computed tomography; MA, Medicare Advantage; TM, traditional Medicare.

Selected procedures including Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes, descriptions, and place of service. Numbers of claims are summed for all payer types (TM, MA, and commercial) across all years (2007-2012). Number of markets includes all CBSAs ever included in the study, although they are not necessarily included for all payer types for all years. Mean TM reimbursement is weighted by MA claims across markets, as described in the text. The interquartile price variation is calculated as the weighted mean of the within-market interquartile range (75th to 25th percentile) for each plan type, divided by the mean TM reimbursement in that market.

Study Variables and Analysis

We constructed measures of the mean price for each service within geographic markets, defined by core-based statistical areas (CBSAs) including the metropolitan divisions therein. The CBSA is a geographic area defined by the Office of Management and Budget to represent an area with commuting ties to an urban center. The 11 largest CBSAs (eg, greater New York City, greater Chicago) are separated into smaller Metropolitan Divisions (eg, 4 Divisions within New York City, 3 Divisions within Chicago), and so we use the smaller Metropolitan Division codes, when applicable, to define the geographic markets within these larger CBSAs. The private insurer’s data include the geographic location of the health care facility at the 3-digit zip code level. We aggregated 3-digit zip codes to CBSAs; because our zip code to CBSA crosswalk is at the 5-digit code level, we exclude underlying data from 3-digit zip codes with ambiguous CBSA classification. Specifically, we retain claims only from 3-digit zip codes whose population cleanly maps into 1 CBSA for at least 70% of the population in that 3-digit zip code.

We evaluated what is commonly referred to as the “allowed amount”—that is, the contracted rate that the plan agreed to pay the clinician for the service, after any contractual discounts. This reflects the total payment made to the clinician or health care facility by both the insurer and the patient (in the form of cost-sharing). We excluded claims with modifier codes that reflect different levels of reimbursement and selected claims with the main unit of measure for the specific procedure. For example, we excluded claims paid (primarily by health maintenance organizations) using monthly units, which likely represent capitated payments. This resulted in excluding 26% of claims for our selected procedures, most of which were claims for physician office visits and laboratory tests.

We computed the mean price for each service, by plan type, place of service, CBSA, and year. We then calculated the mean price for each service as a percent of the mean traditional Medicare rate for that same service within each CBSA, separately for MA and commercial patients. We then averaged these relative mean prices across CBSAs within each year, weighting by the private insurer’s enrollment in the given CBSA and line of business. The private insurer has a broader presence in the MA market than the commercial market, which means that we observe MA data in CBSAs where we do not observe adequate commercial data. Because this analysis is primarily focused on MA prices, we did not want to exclude the MA data from these CBSAs without commercial data; however, constructing common weights to aggregate across CBSAs would, by definition, impose assumptions about commercial prices in the CBSAs where these data do not exist. We therefore present data using unique weights for MA and commercial plans, representing the insurer’s MA and commercial presence across CBSAs, respectively. However, that limits the ability to compare relative prices (relative to traditional Medicare) across the MA and commercial markets because they represent different underlying geographic markets. We present additional results for MA using data only from those CBSAs that also have a commercial presence and common weights in eFigures 1 to 4 in the Supplement. Using these alternative weights, the general findings are substantively unchanged.

We excluded claims with zero or negative payment amounts (1.8% of claims) and with prices more than 4 standard deviations above or below the mean (by payer) as outliers (0.4% of claims). Where we report a single price measure over the full 6-year study period, we averaged these measures across years, giving equal weight to each year. All analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc) and Stata (version 14; StataCorp) software.

Results

From 2007 through 2012, there were a total of 15.0 million claims for MA enrollees, 120.7 million claims for traditional Medicare enrollees, and 8.5 million claims for commercial enrollees included in our study. More detail on each of the procedures, including the mean traditional Medicare reimbursement, the degree of variation in reimbursement (within CBSAs) by plan type, and the number of claims and markets included in our study is available in the Table. For a given service, traditional Medicare reimbursement varies little across physicians within a market, whereas commercial prices vary considerably. There is less within-market variation in MA physician reimbursement than commercial, but somewhat more than traditional Medicare. In contrast, MA reimbursement varies more than commercial for some laboratory services and durable medical equipment (see Table).

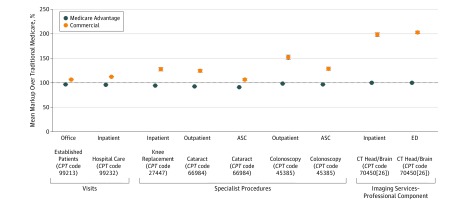

The mean markup over traditional Medicare rates for MA and commercial enrollees is displayed for each physician procedure in Figure 1. Physician reimbursement in MA was similar to or slightly less than traditional Medicare rates. For the most common physician service in our data—a standard mid-level office visit with an established patient (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] 99213)—the mean MA price was 96.9% (95% CI, 96.7%-97.2%) of traditional Medicare. Across the physician services in Figure 1, mean MA reimbursement ranged from 91.3% of traditional Medicare for cataract removal in an ASC (CPT code 66984; 95% CI, 90.7%-91.9%) to 100.2% of traditional Medicare for the professional fee for interpretation of a computed tomographic scan in an emergency department (CPT 70450[26]; 95% CI, 100.0%-100.4%).

Figure 1. Mean Markup Over Traditional Medicare for Physician Services, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients.

Mean prices relative to traditional Medicare are constructed for each of the 6 years in the study period at the core-based statistical area and are aggregated with weights to reflect the geographic distribution of the private insurer’s Medicare Advantage and commercial utilization, respectively. Symbols indicate the ratios of mean prices from 2007 through 2012, and error bars, the 95% CI. Codes are Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. ASC indicates ambulatory surgery center; CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department.

Moreover, for these physician services, there was considerably less variation in mean MA reimbursement (relative to traditional Medicare) across markets compared with commercial reimbursement (eAppendix and eTable in the Supplement). Taken together, these data suggest that traditional Medicare rates tend to represent a strong anchor for physician reimbursement in MA.

In contrast, physician reimbursement for commercial enrollees was higher than under traditional Medicare. The commercial markup over traditional Medicare varied across both type of service (ie, across HCPCS codes) and, for some services, across place of service within a given procedure. For a standard office visit (CPT 99213), the mean physician reimbursement for commercial patients was 107.2% (95% CI, 106.1%-108.3%) of traditional Medicare. Consistent with other work, commercial markups tended to be higher for procedures performed by specialists than for evaluation and management services, which suggests that specialist physicians have stronger negotiating power with insurers than primary care physicians. Additionally, we found higher physician reimbursement for the professional fee (ie, excluding the facility fee) for colonoscopies (CPT 45385) and cataract removals (CPT 66984) when performed in hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) compared with ASCs (for colonoscopy, 152.4% [95% CI, 143.1%-161.7%] in HOPD vs 129.1% [95% CI, 122.8%-135.4%] in ASC; for cataract removal, 125.0% [95% CI, 119.5%-130.5%] in HOPD vs 107.1% [95% CI, 103.7%-110.5%] in ASC); traditional Medicare reimbursement for the professional fee for these procedures does not vary across these sites of care. The higher physician reimbursement in the outpatient setting may reflect the fact that hospitals tend to have stronger bargaining clout to negotiate the professional fees for the physicians who are employed by them compared with the independent practices that tend to perform procedures in ASCs.

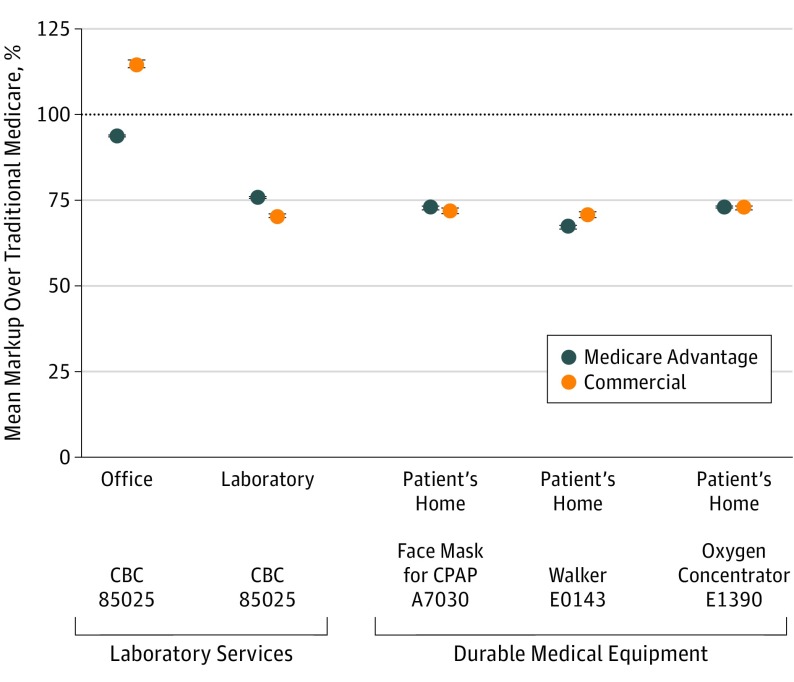

Whereas commercial prices tend to be higher than those of traditional Medicare, there are several services for which commercial prices are actually lower, including tests performed in independent laboratories and durable medical equipment. We found that commercial reimbursement is lower than traditional Medicare for these services and that MA plans take advantage of these lower commercial prices. The mean relative prices for 3 common types of durable medical equipment—a face mask used with a continuous positive airway pressure device (HCPCS A7030), a walker (HCPCS E0143), and an oxygen concentrator (HCPCS E1390)—are displayed in Figure 2. The mean commercial price ranges from 70.5% (walker; 95% CI, 68.9%-72.2%) to 72.8% (oxygen concentrator; 95% CI, 71.8%-73.7%) of traditional Medicare. In each case, the MA reimbursement is similar to these commercial prices—that is, below traditional Medicare. While the gap in pricing has likely narrowed recently due to Medicare implementing a competitive bidding program for durable medical equipment, these findings suggest that private insurers had already been correcting for Medicare’s overpayments.

Figure 2. Mean Markup Over Traditional Medicare for Laboratory Services and Durable Medical Equipment, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients.

Mean prices relative to traditional Medicare are constructed for each of the 6 years in the study period at the core-based statistical area and are aggregated with weights to reflect the geographic distribution of the private insurer’s Medicare Advantage and commercial utilization, respectively. Symbols indicate the ratios of mean prices from 2007 through 2012, and error bars, the 95% CI. Codes are Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes. CBC indicates complete blood cell count; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure.

Commercial reimbursement for laboratory testing varies substantially depending on the place of service, whereas traditional Medicare’s rates did not vary across place of service during the study period. For a complete blood cell count (CPT 85025), the mean commercial prices were 114.5% (95% CI, 112.1%-116.9%) and 70.4% (95% CI, 69.4%-71.3%) of traditional Medicare when billed by a physician’s office and an independent laboratory, respectively. In the physician’s office setting, where commercial plans paid more than traditional Medicare, mean MA reimbursement was similar to the traditional Medicare rate (93.9%; 95% CI, 93.3%-94.4%). In the independent laboratory setting, where commercial plans paid less than traditional Medicare, MA plans also paid these below-Medicare prices (75.8% for MA; 95% CI, 75.0%-76.6%; 70.4% for commercial; 95% CI, 69.4%-71.3%).

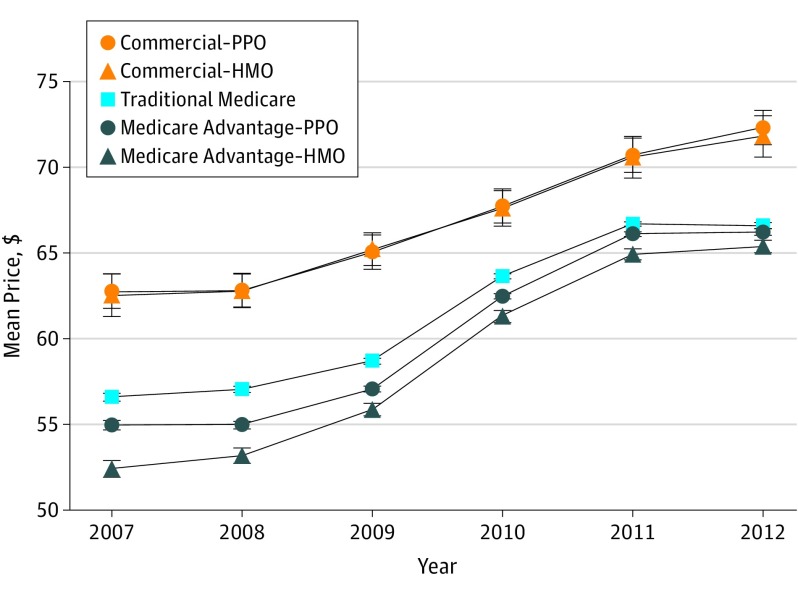

Changes over time in mean physician reimbursement for an office visit (CPT 99213) for enrollees in different plan types are displayed in Figure 3. The mean traditional Medicare rate increased 17.6% over the study period, from $56.60 (95% CI, $56.15-$57.05) in 2007 to $66.58 (95% CI, $66.24-$66.93) in 2012; however, this increase was nonlinear over the study period, with considerable increases in 2010 and 2011, largely due to Medicare policy changes intended to increase payments for primary care services. While mean reimbursement varies across market segments, the patterns in reimbursement increases are similar, suggesting that traditional Medicare rates, and Medicare policies that affect these rates, have an important influence on price negotiations between insurers and clinicians or health care institutions for enrollees in MA and commercial plans. In addition, Figure 3 indicates that physician reimbursement for office visits was lower for MA health maintenance organization enrollees compared with MA preferred provider organization enrollees, although the differential narrowed over the study period.

Figure 3. Mean Price Paid for Physician Office Visit by Plan Type, for Commercial, Medicare Advantage, and Traditional Medicare Patients.

Mean prices are constructed for each of the 6 years in the study period at the core-based statistical area and are aggregated with weights to reflect the geographic distribution of the private insurer’s Medicare Advantage utilization for the Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare numbers and with the private insurer’s commercial utilization for the commercial numbers. Enrollment in point of service plans is included in health maintenance organization (HMO) enrollment. PPO indicates preferred provider organization. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

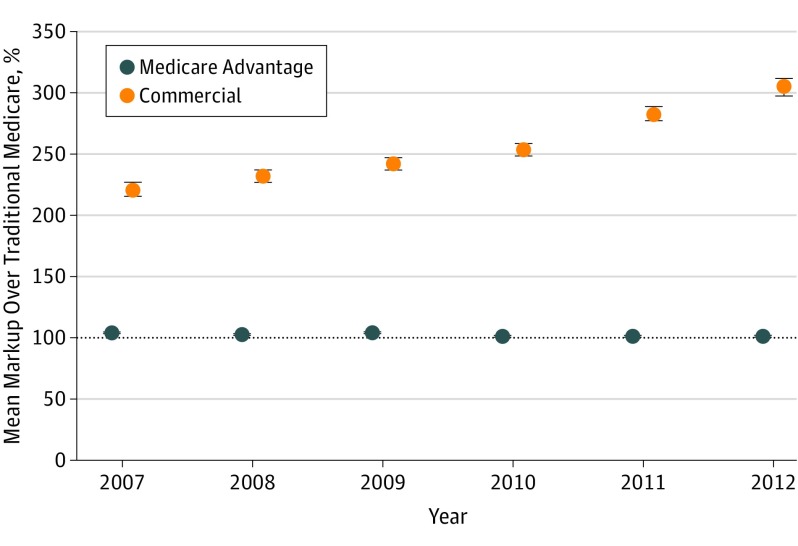

Mean physician reimbursement for complex evaluation and management of a patient in the emergency department (CPT 99285) by market segment and year is displayed in Figure 4. Medicare Advantage clinician reimbursement amounted to a mean of 102.3% (95% CI, 102.1%-102.6%) of that of traditional Medicare over the study period and was relatively stable. In contrast, the mean markup of commercial prices over traditional Medicare increased from 222.1% (95% CI, 209.3%-235.0%) in 2007 to 306.2% (95% CI, 292.5%-319.8%) in 2012. Whereas the commercial markup over traditional Medicare did increase over the study period for several other procedures that we evaluated, the rate of increase of these commercial prices for emergency visits was an important outlier, which may reflect the substantial consolidation among emergency-based physician practices that has occurred in recent years. However, the contrast between the substantial price increases in the commercial market compared with the relative stability in the MA market also suggests that MA market dynamics are able to constrain the impact of such consolidation of health care professionals whereas commercial markets face the brunt of its implications.

Figure 4. Mean Markup Over Traditional Medicare for Physician Visits in the Emergency Department, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients.

Mean prices relative to traditional Medicare are constructed for each of the 6 years in the study period at the core-based statistical area and are aggregated with weights to reflect the geographic distribution of the private insurer’s Medicare Advantage and commercial utilization, respectively. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

From 2007 through 2012, physician reimbursement in MA was more strongly tied to traditional Medicare rates than negotiated commercial prices, although MA plans tended to pay physicians less than traditional Medicare rates. This finding is consistent with prior research in the hospital setting. However, we found that MA plans tend to benefit from the commercial market’s favorable pricing for a few select services for which traditional Medicare overpays. Our findings, taken together with prior work, suggest that traditional Medicare rates tend to represent a strong anchor for MA clinician reimbursement for most physician and hospital services but that MA plans take advantage of commercial plans’ leverage where traditional Medicare is overpaying for services. Several recent payment reforms in the traditional Medicare program have attempted to address these overpayments, including CMS’s recent implementation of a competitive bidding program for durable medical equipment and a policy scheduled to take effect in 2018 changing Medicare reimbursement for laboratory tests to be lower in independent laboratories than in physicians’ offices. Whereas these policy changes represent improvements to CMS’s payment formulas, the fact that MA plans have been benefitting from favorable pricing for these services back to at least 2007 suggests that private MA health insurers have been able to take advantage of the private market’s correction for these traditional Medicare pricing failures for many years. However, laboratory services and durable medical equipment represent a small fraction of total Medicare spending (<3% in 2016 combined); thus, for physician and hospital services, which constitute most of Medicare spending, MA plans tend to pay clinicians near traditional Medicare rates.

Limitations

Our findings have some important limitations. First, the MA and commercial data included in our study are only from 1 insurer and therefore may not necessarily be representative of the experience of other private insurers or of geographic locations not served by this particular insurer. However, the insurer has a large presence in the MA market and thus the findings are reflective of common pricing patterns in the MA market. In addition, we were unable to assess payment to health care professionals under capitated arrangements due to data limitations, so the extent to which our findings reflect clinician payment in capitated settings is unclear. We were also unable to link clinicians across the private insurer’s claims data and the traditional Medicare claims data, so we could not evaluate the extent to which reimbursement differences across market segments could reflect a different distribution or network of health care institutions serving MA and traditional Medicare patients. For example, in an analysis of MA payment rates to hospitals, Baker et al found that accounting for the differences in the networks of hospitals treating MA patients narrowed the differences in MA and traditional Medicare payments by approximately 30%. We are unable to make such adjustments with our data, which may suggest that our findings overstate any differences in MA physician reimbursement compared with traditional Medicare. However, there is less variation in the traditional Medicare fee schedule for a given physician service within a local geographic market than there is for a given hospitalization across hospitals within a market, and thus adjusting for these network differences would likely make less of a difference for physician reimbursement compared with hospitals. We were also unable to assess the extent to which differences in mean prices may reflect other clinician-level factors, such as quality, and whether there were any differences across payers outside of direct reimbursement, such as pay-for-performance bonuses or penalties.

There are several likely explanations for our main finding that MA clinician reimbursement is more strongly tied to traditional Medicare than to the insurer’s negotiated commercial prices, particularly for physician services. Consistent with previous expositions, we believe that the main drivers of this are (1) the fact that CMS payments to MA plans are largely based on spending in the traditional Medicare program and (2) the existence of regulations substantially restricting balance billing of MA patients who undergo treatment by out-of-network clinicians. Regarding the former, traditional Medicare rates likely provide a strong anchor on price negotiations between MA plans and clinicians because, in the extreme, if clinicians or health care institutions were to charge prices that are considerably higher than traditional Medicare rates while payments to MA plans are based on formulas tied to traditional Medicare spending (and thus rates), then insurers would likely abandon MA and enrollees would return back to the traditional Medicare program in which clinicians would be paid at traditional Medicare rates. Thus, attempts by health care professionals to charge substantial markups over traditional Medicare rates (such as at commercial prices) would likely be a strategy with only short-term viability.

Another important policy constraining MA clinician prices to traditional Medicare rates is the existence of a Medicare statute and implementing regulation that limit the ability of clinicians participating in the traditional Medicare program to bill out-of-network MA enrollees at higher than traditional Medicare rates. Specifically, even if a clinician chooses not to participate in an MA plan’s network but provides care to an MA enrollee as an out-of-network provider, they cannot charge that MA patient more than traditional Medicare’s rate for that service. If the physician is “nonparticipating” in the traditional Medicare program, meaning that he or she does not agree to accept Medicare rates as payment in full, then that physician is allowed to balance bill patients, but with limits on this balance billing, resulting in total payment that is 109.25% of the traditional Medicare rate. (Few physicians who treat Medicare patients are nonparticipating.) These restrictions limit clinician bargaining leverage in negotiations with MA plans, particularly for services that commonly occur out-of-network such as emergency services, because clinicians are not able to charge substantially higher prices for services delivered out-of-network, which mitigates the price incentive for the clinician to stay out-of-network and thus increases the insurer’s bargaining power vis-à-vis the clinician.

The contrast between the markup over traditional Medicare for commercial and MA prices, particularly for physician services in the emergency department, and the substantial increase in this commercial markup over the study period suggests that this type of regulation limiting balance billing for out-of-network services could potentially provide an important restraint on clinician market power in the commercial market. Several policy proposals have been implemented and/or put forth to regulate balance billing in the commercial market for clinicians and health care services that patients do not choose, often referred to as “surprise medical billing.” For services such as emergency department visits, in which a large proportion of billing could be affected by such policies, the findings from our analysis suggest that this could also constrain clinician prices for in-network contracting, as seen in MA. Broader billing limits could affect the negotiated prices for many more services, but we do not perceive this to be on the policy agenda at this point.

Finally, our analysis suggests that Medicare payment policies play a strong role in negotiations for many physician services in the broader market, as both MA and commercial prices for physician office visits increased concurrent to CMS policies increasing Medicare payments for these services (as seen in Figure 3). This finding is consistent with prior research, which found that major Medicare payment policy changes in the 1990s affected reimbursement in the commercial market, particularly for office visits. Our findings suggest that traditional Medicare rates continue to be a prominent anchor for price negotiations for physician services and, moreover, that this is true for both the commercial and MA markets.

This finding has important implications for policy proposals related to transitioning traditional Medicare to a premium support model. Sometimes referred to as a defined contribution or voucher approach, premium support involves the federal government providing a payment on behalf of each Medicare beneficiary toward the purchase of a health insurance plan. Such proposals generally aim to reduce growth in Medicare spending by relying on both increased competition among insurers providing privatized Medicare benefits (such as MA) and incentivizing beneficiaries to choose lower-cost plans. Although the details of such proposed reforms vary, generally speaking, the traditional Medicare program would likely have reduced enrollment—or cease to exist entirely. Our findings reinforce prior modeling assumptions made by the Congressional Budget Office, suggesting that this transition could have important implications for clinician prices in both the MA and commercial markets. That is, it is unclear what, if anything, would anchor clinician price negotiations absent the presence of traditional Medicare’s rates, but it is likely that the dissolution of traditional Medicare would result in increased clinician prices paid by private plans serving Medicare beneficiaries—although projections of the fiscal impact of such a development would discourage such a policy change. To the extent that the traditional Medicare program continues but with reduced market share, it may still restrain clinician pricing demands on MA plans. Like today, higher prices than traditional Medicare would shift enrollment back to that program. In addition, restrictions on balance billing in Medicare and MA would limit pricing demands. However, these constraints would disappear if the traditional program were abolished.

Conclusions

Physician reimbursement in MA is more strongly tied to traditional Medicare than to commercial prices, but MA plans take advantage of favorable commercial prices for services for which traditional Medicare overpays. Commercial markups over traditional Medicare vary across physician services, with striking increases in these markups for emergency department visits in recent years. Traditional Medicare’s administratively set rates, and the statutes and implementing regulations that limit billing out-of-network MA enrollees above these rates, play an important role in influencing clinician reimbursement in MA. Current policy proposals that would substantially affect traditional Medicare’s role, such as fully transitioning to a premium support model, would have broad implications for clinician reimbursement and thus the affordability of such a reformed Medicare program. In addition, implementing regulations limiting the amount that clinicians can bill for out-of-network enrollees in the commercial market, as currently exist in MA, may help to provide some check on clinician market power and constrain commercial markups, particularly in the emergency department setting.

eAppendix. Distribution of Prices Relative to Traditional Medicare Across Markets

eTable. Distribution of Mean Price Relative to Traditional Medicare Across Markets

eFigure 1. Average Mark-up Over Traditional Medicare for Physician Services, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients

eFigure 2. Average Mark-up Over Traditional Medicare for Lab Services and Durable Medical Equipment, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients

eFigure 3. Average Price Paid for Physician Office Visit by Plan Type, for Commercial, Medicare Advantage, and Traditional Medicare Patients

eFigure 4. Average Mark-up Over Traditional Medicare for Physician Visits in the Emergency Department, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients

References

- 1.Ginsburg PB. Wide Variation in Hospital and Physician Payment Rates Evidence of Provider Market Power Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2010. Research brief 16. [PubMed]

- 2.Austin DR, Baker LC. Less physician practice competition is associated with higher prices paid for common procedures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1753-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker L, Bundorf MK, Royalty A. Private insurers’ payments for routine physician office visits vary substantially across the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(9):1583-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper Z, Craig S, Gaynor M, Van Reenan J. The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2015. NBER working paper 21815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Royalty AB, Levin Z. Physician practice competition and prices paid by private insurers for office visits. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1653-1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson G, Cassillas G, Damico A, Neuman T, Gold M Medicare Advantage 2016 Spotlight: Enrollment Market Update. Kaiser Family Foundation website. 2016. http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2016-spotlight-enrollment-market-update/. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 7.Ryan P. A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America. 2016. http://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-HealthCare-PolicyPaper.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 8.Berenson RA, Sunshine JH, Helms D, Lawton E. Why Medicare Advantage plans pay hospitals traditional Medicare prices. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1289-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Congressional Budget Office (CBO) A premium support system for Medicare: analysis of illustrative options . Washington, DC: CBO; 2013. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/PremiumSupport_OneColumn.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 10.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Devlin AM, Kessler DP. Medicare Advantage plans pay hospitals less than traditional Medicare pays. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1444-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curto V, Einav L, Finkelstein A, Levin JD, Bhattacharya J. Healthcare Spending and Utilization in Public and Private Medicare Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2017. NBER working paper 23090.

- 12.Maeda JL, Nelson L. An Analysis of Private-Sector Prices for Hospital Admissions Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2017. CBO working paper 2017-02.

- 13.White C, Bond AM, Reschovsky JD. High and Varying Prices for Privately Insured Patients Underscore Hospital Market Power Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2013. Research brief 27. [PubMed]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services DMEPOS Competitive Bidding – Home. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/DMEPOSCompetitiveBid/index.html. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, HHS Medicare program; payment policies under the physician fee schedule and other revisions to Part B for CY 2010: final rule with comment period. Fed Regist. 2009;74(226):61737-62188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song Z, Ayanian JZ, Wallace J, He Y, Gibson TB, Chernew ME. Unintended consequences of eliminating Medicare payments for consultations. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(1):15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reschovsky JD, Ghosh A, Stewart K, Chollet D. Paying More for Primary Care: Can It Help Bend the Medicare Cost Curve? New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2012. [PubMed]

- 18.Consolidation: are two heads better than one? Emergency Physicians Monthly website. http://epmonthly.com/article/consolidation-are-two-heads-better-than-one/. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 19.Office of Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services Medicare home oxygen equipment: cost and servicing. 2006. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-04-00420.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 20.Office of Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services Comparison of prices for negative pressure wound therapy pumps. 2009. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-07-00660.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 21.Office of Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services Comparing lab test payment rates: Medicare could achieve substantial savings. 2013. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-07-11-00010.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 22.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare program: Medicare clinical diagnostic laboratory tests payment system; final rule. Fed Regist. 2016;81(121):41036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Data book: health care spending and the Medicare program. 2016. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/june-2016-data-book-health-care-spending-and-the-medicare-program.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 24.Office of Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services Medicare payments for clinical diagnostic laboratory tests in 2015: year 2 of baseline data. 2016. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-16-00040.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 25.Congressional Budget Office A premium support system for Medicare: analysis of illustrative options. 2013. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/44581. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 26.Social Security Act, Agreements With Providers of Services; Enrollment Processes, 42 USC §1866(a)(1)(O) (2015).

- 27.Social Security Act, Payments to Health Maintenance Organizations and Competitive Medical Plans, 42 USC §1876(j)(1) (2015).

- 28.Special Rules for Services Furnished by Noncontract Providers, 42 CFR §422.214 (2016).

- 29.Murray R. Hospital charges and the need for a maximum price obligation rule of emergency department & out-of-network care. Health Affairs Blog website. May 16, 2013. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/05/16/hospital-charges-and-the-need-for-a-maximum-price-obligation-rule-for-emergency-department-out-of-network-care/. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 30.Hoadley J, Ahn S, Lucia K Balance billing: how are states protecting consumers from unexpected charges? Center on Health Insurance Reforms, Georgetown University Health Policy Institute. 2015. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2015/rwjf420966. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 31.Hall MA, Ginsburg PB, Lieberman SM, Adler L, Brandt C, Darling M Solving surprise medical bills. 2016. Brookings Institution white paper. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/sbb1.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2017.

- 32.Clemens J, Gottlieb J. In the shadow of a giant: Medicare’s influence on private physician payments. J Polit Econ. 2017;125(1):1-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobson G, Neuman T Turning Medicare into a premium support system: frequently asked questions. Kaiser Family Foundation Issue Brief; July 19, 2016. http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/turning-medicare-into-a-premium-support-system-frequently-asked-questions/. Accessed June 6, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Distribution of Prices Relative to Traditional Medicare Across Markets

eTable. Distribution of Mean Price Relative to Traditional Medicare Across Markets

eFigure 1. Average Mark-up Over Traditional Medicare for Physician Services, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients

eFigure 2. Average Mark-up Over Traditional Medicare for Lab Services and Durable Medical Equipment, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients

eFigure 3. Average Price Paid for Physician Office Visit by Plan Type, for Commercial, Medicare Advantage, and Traditional Medicare Patients

eFigure 4. Average Mark-up Over Traditional Medicare for Physician Visits in the Emergency Department, for Medicare Advantage and Commercial Patients