Abstract

Rationale: Low-Vt ventilation lowers mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) but is underused. Little is known about clinician attitudes toward and perceived barriers to low-Vt ventilation use and their association with actual low-Vt ventilation use.

Objectives: The objectives of this study were to assess clinicians’ attitudes toward and perceived barriers to low-Vt ventilation (Vt <6.5 ml/kg predicted body weight) in patients with ARDS, to identify differences in attitudes and perceived barriers among clinician types, and to compare attitudes toward and perceived barriers to actual low-Vt ventilation use in patients with ARDS.

Methods: We conducted a survey of critical care physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists at four non–ARDS Network hospitals in the Chicago region. We compared survey responses with performance in a cohort of 362 patients with ARDS.

Results: Survey responses included clinician attitudes toward and perceived barriers to low-Vt ventilation use. We also measured low-Vt ventilation initiation by these clinicians in 347 patients with ARDS initiated after ARDS onset as well as correlation with clinician attitudes and perceived barriers. Of 674 clinicians surveyed, 467 (69.3%) responded. Clinicians had positive attitudes toward and perceived few process barriers to ARDS diagnosis or initiation of low-Vt ventilation. Physicians had more positive attitudes and perceived fewer barriers than nurses or respiratory therapists. However, use of low-Vt ventilation by all three clinician groups was low. For example, whereas physicians believed that 92.5% of their patients with ARDS warranted treatment with low-Vt ventilation, they initiated low-Vt ventilation for a median (interquartile range) of 7.4% (0 to 14.3%) of their eligible patients with ARDS. Clinician attitudes and perceived barriers were not correlated with low-Vt ventilation initiation.

Conclusions: Clinicians had positive attitudes toward low-Vt ventilation and perceived few barriers to using it, but attitudes and perceived process barriers were not correlated with actual low-Vt ventilation use, which was low. Implementation strategies should be focused on examining other issues, such as ARDS recognition and process solutions, to improve low-Vt ventilation use.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, quality improvement, survey, intensive care unit

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is common and associated with significant morbidity and mortality (1–3). Low-Vt ventilation lowers mortality resulting from ARDS (4–6). In previous surveys, researchers explored some of the barriers to low-Vt ventilation use by ARDS Network (ARDSNet) clinicians (physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists [RTs]). They identified physician unwillingness to relinquish ventilator control; failure to recognize ARDS; perceptions of contraindications; and other organizational, attitudinal, and knowledge-related barriers to low-Vt ventilation use (7, 8). These previous researchers did not report the relationships between these potential barriers or perception of performance and actual use of low-Vt ventilation.

As previously shown, low-Vt ventilation is underused at four Chicago area hospitals (9). We conducted a survey among the critical care clinicians at these hospitals to identify attitudes toward and perceived barriers to use of low-Vt ventilation. In addition, we aimed to compare clinician attitudes and perceived barriers with actual use of low-Vt ventilation. We hypothesized that clinicians would have generally positive attitudes and perceive few barriers to low-Vt ventilation use, as well as that clinicians with the most positive attitudes and fewest perceived barriers would be correlated with increased initiation of low-Vt ventilation in actual practice.

Methods

Setting and Sampling Frame

The study was approved with a waiver of patient consent by the institutional review boards of Northwestern University and the participating hospitals. Clinicians provided consent during the survey process. The study was performed in nine adult intensive care units (ICUs) at four Chicago area hospitals: an academic, tertiary care hospital and three community hospitals. Physician staffing in eight ICUs included primary coverage or mandatory consultation by board-certified critical care physicians, and one ICU was staffed by cardiologists. In ICUs with dual coverage (e.g., a primary team and a mandatory consulting critical care physician), we surveyed only critical care physicians. All ICUs were staffed by specially trained ICU nurses and RTs. Academic hospital ICUs also included fellows and residents. None of the sites had ARDS protocols.

Survey Development

The objectives of the survey were to identify clinician attitudes toward and perceived barriers to use of low-Vt ventilation. The low-Vt ventilation survey was part of a larger survey that also assessed clinician attitudes toward and perceived barriers to use of awake and breathing controlled ventilator weaning, as well as clinician social networks (10–12). The survey was conceptually based on the theory of planned behavior and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (13, 14).

On the basis of the literature and expert opinion, we identified two topics important for understanding low-Vt ventilation use: clinician attitudes toward low-Vt ventilation and perceived process barriers affecting adoption of low-Vt ventilation. In addition, we sought to explore three additional topics: anticipated regret, clinician risk taking when making patient care decisions, and perceived communication among clinicians. We did not explicitly define low-Vt ventilation on the survey. Demographic questions were included. Individual items were based on existing surveys (Evidence-Based Practice Attitudes Survey, Survey of Ventilator Management in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome) and author opinion (8, 15, 16). We conducted multiple rounds of review of each item’s context and stem construction, as well as response item wording and ordering.

We pretested the survey with five clinicians, interviewing them about item clarity and comprehension, style, formatting, and length. On the basis of pretesting, the survey underwent further revisions until the final versions were completed (see the online supplement). The final survey was pilot tested with 23 clinicians to establish administration procedures.

Survey Administration

All attending physicians and fellows who cared for the patients in a previously reported cohort of 362 patients with ARDS, which was developed in a retrospective cross-sectional study from June to December, 2013, were recruited to complete the survey (9). We obtained names and contact information of all ICU nurses and RTs at participating hospitals at the time of the survey. We sent a recruitment e-mail to eligible clinicians using SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey, Inc., San Mateo, CA) (17). The e-mail contained a link allowing clinicians to complete the survey online. Clinicians who did not access the online survey within 7 days received a reminder e-mail. Upon completion, clinicians received a $20 electronic gift card. We attempted to hand deliver a paper version of the survey with a stamped return envelope and a $20 bill to clinicians who did not access the online survey. The survey was distributed and results were collected between October 2014 and June 2015.

ARDS Cohort

We previously reported the construction of the ARDS patient cohort in this study (9). We used the Berlin Definition to define ARDS (3). We developed criteria for identifying bilateral infiltrates, ARDS risk factors, and objective assessment of cardiac failure (9). We collected all ventilator settings. Consistent with the ARDSNet adherence threshold, we defined low-Vt ventilation as any Vt less than 6.5 ml/kg predicted body weight (PBW) occurring after ARDS onset (18). We did not consider a plateau pressure cutoff (e.g., >30 cm H2O), because (1) it was not recorded at two hospitals; (2) some evidence shows low Vt improves outcomes regardless of a plateau pressure cutoff (19); and (3) the ARDSNet protocol requires initiating lower Vt first, which would be captured by the use variable we measured (4). We did not adjust for acidemia, because it did not predict low-Vt ventilation use (9).

Clinician Initiation of Low-Vt Ventilation

We identified the attending critical care physician for each patient-day by who wrote the attending critical care physician progress note for each patient on each date; to ensure accuracy, at two hospitals, we cross-checked these data with which critical care physician billed critical care services. At two hospitals, we identified nurses and RTs according to day and night shifts. The primary nurse was the nurse who entered the greatest number of oxygen saturation entries in the electronic health record during a patient-shift. The primary RT was the RT who entered the greatest number of ventilator settings in the electronic health record during a patient-shift.

We chose low-Vt ventilation initiation as the performance variable for the primary correlations in this study because initiation requires an active change in care, and the survey questions are focused primarily on attitudes and perceived barriers toward the key components in initiating low-Vt ventilation (the diagnosis of ARDS and ordering/administering of low-Vt ventilation). We calculated each clinician’s percentage of patients initiated as the number of patients initiated on low-Vt ventilation after ARDS onset divided by the number of patients eligible for initiation after ARDS onset. For each individual clinician, a patient was eligible for initiation only if he/she was not already receiving low-Vt ventilation at the time the clinician started taking care of him/her. We included each clinician/patient pairing only once in the denominator for each clinician. Initiating low-Vt ventilation was defined as a patient achieving a Vt less than 6.5 ml/kg PBW after ARDS onset. Each clinician who was caring for a patient when low-Vt ventilation was initiated was credited with initiation. Five patients for whom low-Vt ventilation was initiated more than once after ARDS onset were included as eligible and initiated on each separate occasion. Additional details of these methods are included in the Methods section of the online supplement.

Sensitivity Analysis

To determine whether our results were sensitive to a less restrictive definition of low-Vt ventilation, we linked attending physicians with the time frames in which each patient was initiated on a Vt less than 8 ml/kg PBW. This is a more lenient definition of low-Vt ventilation that includes the upper 95% confidence interval for the low-Vt arm of the ARDSNet study (4).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for clinician characteristics and each survey question. Initiation of low-Vt ventilation was reported as the median (interquartile range [IQR]) percentage of patients who were initiated for each group of clinicians. We categorized clinicians as having 10 or fewer years of experience or 11 or more years of experience and compared survey questions, initiation of low-Vt ventilation, and initiation of Vt less than 8 ml/kg PBW (attending physicians) between experience categories using Fisher’s exact test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Pairwise comparisons of individual survey questions between clinician groups were performed using Student’s t test or the chi-square test. The Bonferroni correction was used to account for the three pairwise tests for each question; for these comparisons, P < 0.017 was considered significant.

The Spearman correlation was used to evaluate the association between each survey question and initiation of low-Vt ventilation. Also, we examined the correlations between attending physician survey responses and initiation of an alternate Vt cutoff of less than 8 ml/kg PBW. P < 0.05 was considered significant. We used SAS version 9.4 software for analyses (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Six hundred seventy-four clinicians were eligible, and 467 (69.3%) consented and responded to at least one question. There were no differences in the response rates across clinician types (physicians, 68.0%; nurses, 70.7%; RTs, 65.3%). At the academic hospital, there was no difference in the percentage of physician survey responders who were attending physicians (as opposed to fellows) compared with nonresponders (66.3% vs. 59.5%; P = 0.46). Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Survey respondent demographics

| Characteristic | Physicians (n = 83) | Nurses (n = 307) | Respiratory Therapists (n = 77) | All Clinicians (n = 467) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, n (%) | ||||

| Under 25 | 0 | 38 (13.5) | 1 (1.3) | 39 (8.9) |

| 25–34 | 25 (30.9) | 142 (50.4) | 26 (34.2) | 193 (44.0) |

| 35–44 | 32 (39.5) | 52 (18.4) | 15 (19.7) | 99 (22.6) |

| 45–54 | 14 (17.3) | 31 (11.0) | 19 (25.0) | 64 (14.6) |

| 55–64 | 10 (12.4) | 18 (6.4) | 13 (17.1) | 41 (9.3) |

| 65 and older | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.6) | 3 (0.7) |

| No response | 2 | 25 | 1 | 28 |

| Female, n (%)* | 22 (26.8) | 242 (86.4) | 45 (60.0) | 309 (70.7) |

| Physician level† | ||||

| Attending, n (%) | 53 (66.3) | |||

| Fellow, n (%) | 27 (33.8) | |||

| No response | 3 | |||

| Years since training completion† | ||||

| Still in training | 24 (30.0) | 24 (8.6) | 0 | 48 (11.1) |

| 5 or fewer | 22 (27.5) | 156 (55.7) | 17 (23.0) | 195 (44.9) |

| 6–10 | 8 (10.0) | 33 (11.8) | 23 (31.1) | 64 (14.7) |

| 11–15 | 9 (11.3) | 30 (10.7) | 4 (5.4) | 43 (9.9) |

| 16–20 | 5 (6.3) | 6 (2.1) | 8 (10.8) | 19 (4.4) |

| 21–25 | 5 (6.3) | 8 (2.9) | 6 (8.1) | 19 (4.4) |

| 26–30 | 4 (5.0) | 12 (4.3) | 5 (6.8) | 21 (4.8) |

| 31 or more | 3 (3.8) | 11 (3.9) | 11 (14.9) | 25 (5.8) |

| No response | 3 | 27 | 3 | 33 |

No response: 1 physician, 27 nurses, and 2 respiratory therapists.

Physicians: time since fellowship completion. Nurses: time since critical care training/orientation completion. Respiratory therapists: time since respiratory therapy training completion.

Survey Results

For detailed survey results, see Table 2 as well as Tables E1 and E2 in the online supplement.

Table 2.

Survey results for attitude toward and perceived barriers to low-Vt ventilation

| Item | Response | Physicians, Mean (SD) | Nurses, Mean (SD) | Respiratory Therapists, Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward low-Vt ventilation | ||||

| What percentage of your patients with ARDS warrant treatment with LTVV based on the best available evidence? | Percentage as continuous variable | 92.5% (15.3%) | 61.1% (29.5%)* | 67.8% (26.8%)* |

| What percentage of your patients with ARDS have contraindications to receiving LTVV? | Percentage as continuous variable | 7.8% (9.6%) | 24.8% (20.4%)* | 20.5% (17.8%)* |

| Response | Physicians (n [%]) | Nurses (n [%]) | Respiratory Therapists (n [%]) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude toward LTVV ventilation | ||||

| How strong do you believe the evidence is that your patients with ARDS will benefit from LTVV? | Very strong or strong | 80 (96.4) | 195 (66.6)* | 60 (77.9)* |

| In your opinion, how large is the benefit of LTVV in reducing mortality for your ARDS patients? | Very large or large | 56 (67.5) | 146 (50.9)* | 41 (54.0) |

| Level of agreement or disagreement: I will only order/administer [nurses/respiratory therapists: administer] LTVV if I am certain my patient has ARDS. | Strongly disagree or disagree | 67 (80.7) | 78 (26.7)* | 28 (36.8)* |

| Perceived barriers to LTVV | ||||

| Level of agreement or disagreement: It is easy for me to obtain all the information I need to determine whether a patient has ARDS. | Strongly agree or agree | 72 (87.8) | 189 (66.3)* | 63 (81.8)† |

| Level of agreement or disagreement: It is easy to make sure a patient is receiving LTVV. | Strongly agree or agree | 70 (86.4) | 230 (81.6) | 68 (88.3) |

| Level of agreement or disagreement: It is easy to order [nurses/respiratory therapists: initiate and administer] LTVV. | Strongly agree or agree | 75 (91.5) | 214 (76.4)* | 68 (89.5)† |

| How long does it usually take from the time a patient clinically develops ARDS to the time you receive all the information needed to make a diagnosis of ARDS? | Less than 6 h or 6 h to just under 12 h | 71 (86.6) | 189 (67.0)* | 52 (68.4)* |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: obtaining a chest radiograph and being notified of the results. | Never or rarely | 66 (80.5) | — | — |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: obtaining an arterial blood gas and being notified of the results. | Never or rarely | 68 (82.9) | — | — |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: finding time to review all the patient’s records and decide whether to make a diagnosis of ARDS. | Never or rarely | 50 (61.0) | — | — |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: not promptly recognizing that a patient has ARDS even when all data are available and the criteria appear to be met. | Never or rarely | 55 (67.1) | — | — |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: the time from ordering LTVV to your patient receiving it. | Never or rarely | 53 (64.6) | — | — |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; LTVV = low-Vt ventilation.

P < 0.017 for comparison with physicians.

P < 0.017 for comparison with nurses.

Attitudes toward low-Vt ventilation

The mean (SD) percentage of their patients with ARDS who physicians believed warranted treatment with low-Vt ventilation was 92.5% (15.3%), which was higher than among nurses (61.1% [29.5%]) and RTs (67.8% [26.8%]) (P < 0.01 for both comparisons with physicians). Nearly all physicians (96.4%) and majorities of nurses (66.6%) and RTs (77.9%) believed that the evidence for low-Vt ventilation was strong or very strong; physician belief was stronger (P < 0.01 for comparisons with nurses and RTs). Most clinicians believed that low-Vt ventilation provided a large or very large clinical benefit in reducing mortality. Physicians reported fewer patients with contraindications to low-Vt ventilation than nurses and RTs did.

Perceived process barriers to using low-Vt ventilation in ARDS

Most clinicians agreed or strongly agreed that it is easy to obtain information needed to diagnose ARDS, make sure a patient is receiving low-Vt ventilation, and order or administer low-Vt ventilation. Most clinicians reported that it took less than 12 hours to receive the information needed to diagnose ARDS (physicians, 86.6%; nurses, 67.0%; RTs, 68.4%; P < 0.01 for physicians compared with nurses and RTs). Majorities of physicians said there rarely were delays in diagnosing ARDS due to obtaining a chest radiograph (80.5%), sending for arterial blood gas analysis (82.9%), reviewing patient records (61.0%), or recognizing that a patient has ARDS when all data are available (67.1%). Physicians did not report delays in initiating low-Vt ventilation due to delays between the time of ordering it and actually administering it (64.6%).

Initiation of low-Vt ventilation

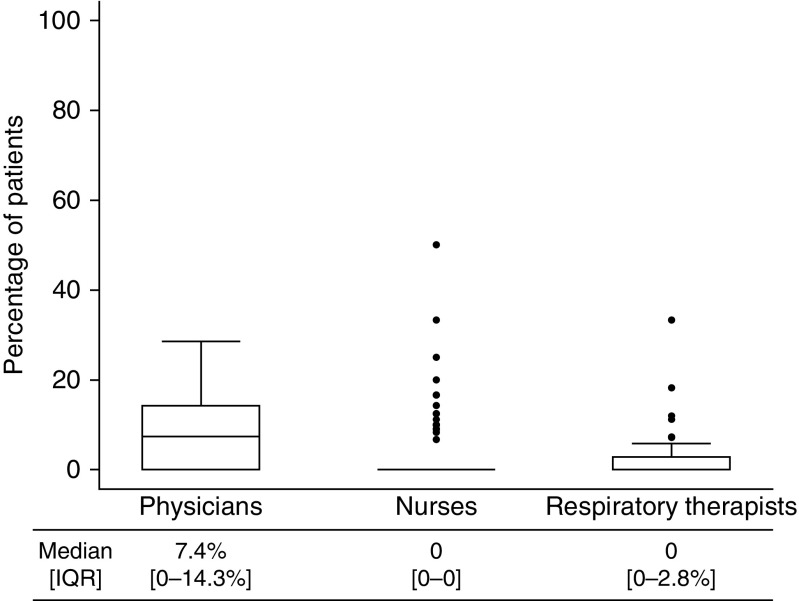

There were 46 attending physicians, 171 nurses, and 51 RTs who were survey responders and also had performance data. The median (IQR) percentage of patients initiated on low-Vt ventilation by survey responders was low (physicians, 7.4% [0 to 14.3%]; nurses, 0 [0–0]; RTs, 0 [0 to 2.8%]) (Figure 1). Among clinicians who did not respond to the survey, low-Vt ventilation initiation was also low and not different from that of survey responders (Table E3). Low-Vt ventilation initiation did not differ when we compared clinicians with 10 or fewer versus 11 or more years in practice (Table E4).

Figure 1.

Initiation of low-Vt ventilation by survey responders (n = 46 for physicians; n = 171 for nurses; n = 51 for RTs). Box plots illustrate the median (interquartile range [IQR]). Whiskers illustrate upper and lower adjacent values (±1.5 times the interquartile difference). Dots represent outliers.

Correlation between Survey Results and Low-Vt Ventilation Initiation

No significant correlation was found between any attending physician attitude or perceived process barrier question and initiation of low-Vt ventilation (Table 3). No significant correlation was found between any nurse or RT attitude or perceived process barrier question and initiation of low-Vt ventilation, except “What percentage of your patients with ARDS have contraindications to receiving low tidal volume ventilation?” For nurses, there was a small positive correlation, and for RTs a small negative correlation, between responses to this question and low-Vt ventilation initiation (Table 3), meaning that nurses who thought patients with ARDS were more likely to have contraindications to low-Vt ventilation had greater proportions treated with it, and the opposite was true for RTs.

Table 3.

Correlation between attitude and perceived barriers survey items and initiation of low-Vt ventilation

| Item | Attending Physicians |

Nurses |

Respiratory Therapists |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient* | P Value | Correlation Coefficient* | P Value | Correlation Coefficient* | P Value | |

| Attitude toward low-Vt ventilation | ||||||

| What percentage of your patients with ARDS warrant treatment with LTVV based on the best available evidence? | −0.29 | 0.85 | 0.057 | 0.47 | 0.072 | 0.62 |

| What percentage of your patients with ARDS have contraindications to receiving LTVV? | −0.28 | 0.058 | 0.17 | 0.031 | −0.28 | 0.044 |

| How strong do you believe the evidence is that your patients with ARDS will benefit from LTVV? | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.044 | 0.57 | 0.0045 | 0.98 |

| In your opinion, how large is the benefit of LTVV in reducing mortality for your ARDS patients? | 0.12 | 0.43 | −0.033 | 0.67 | 0.0082 | 0.95 |

| Level of agreement or disagreement: I will only order/administer LTVV if I am certain my patient has ARDS. | −0.0020 | 0.99 | −0.13 | 0.086 | −0.088 | 0.54 |

| Perceived barriers to low-Vt ventilation | ||||||

| Level of agreement or disagreement: It is easy for me to obtain all the information I need to determine whether a patient has ARDS. | −0.16 | 0.29 | −0.034 | 0.66 | −0.033 | 0.82 |

| Level of agreement or disagreement: It is easy to make sure a patient is receiving LTVV. | −0.22 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.10 |

| Level of agreement or disagreement: It is easy to order [nurses/respiratory therapists: initiate and administer] LTVV. | −0.22 | 0.14 | 0.025 | 0.75 | 0.16 | 0.26 |

| How long does it usually take from the time a patient clinically develops ARDS to the time you receive all the information needed to make a diagnosis of ARDS? | −0.26 | 0.083 | 0.036 | 0.65 | 0.21 | 0.13 |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: obtaining a chest radiograph and being notified of the results. | −0.17 | 0.28 | — | — | — | — |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: obtaining an arterial blood gas and being notified of the results. | 0.0086 | 0.96 | — | — | — | — |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: finding time to review all the patient’s records and decide whether to make a diagnosis of ARDS. | 0.040 | 0.79 | — | — | — | — |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: not promptly recognizing that a patient has ARDS even when all data are available and the criteria appear to be met. | 0.13 | 0.39 | — | — | — | — |

| How often issue delays diagnosis of ARDS or decision to treat with LTVV: the time from ordering LTVV to your patient receiving it. | −0.20 | 0.20 | — | — | — | — |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; LTVV = low-Vt ventilation.

Spearman correlation coefficient.

Sensitivity Analysis

For attending physicians, the median (IQR) percentage of patients initiated on a Vt less than 8 ml/kg PBW was 16.7% (0 to 33.3%). Initiation of Vt less than 8 ml/kg PBW did not differ between physicians with 10 or fewer versus 11 or more years in practice (Table E5). No correlation was found between any attending physician attitude question and initiation of Vt less than 8 ml/kg PBW. There was a significant correlation for two perceived process barrier questions and initiation of Vt less than 8 ml/kg PBW: (1) ease of ordering low-Vt ventilation and (2) length of time to receive information necessary to diagnose ARDS (both negatively correlated with initiation of Vt <8 ml/kg PBW) (Table E6). Additional results are included in Tables E7–E10 and the Results section of the online supplement.

Discussion

In this multicenter, multidisciplinary survey of 467 critical care clinicians at one academic and three community non-ARDSNet hospitals, clinicians had positive attitudes toward using low-Vt ventilation for ARDS and rarely perceived significant barriers to the diagnosis of ARDS or the use of low-Vt ventilation. In a group of hospitals where only 19.3% of patients with ARDS received low-Vt ventilation (9), clinicians reported that most patients with ARDS warrant treatment with low-Vt ventilation, including physicians who reported that 92.5% of their patients with ARDS warranted treatment with low-Vt ventilation. However, low-Vt ventilation use in patients with ARDS cared for by these clinicians was very low, and there were almost no significant correlations between attitudes toward or perceived process barriers to low-Vt ventilation and actual low-Vt ventilation initiation, suggesting a striking divergence between perceptions and observed practice.

Previous studies have suggested several potential barriers to low-Vt ventilation use, including negative clinician attitudes, perceived contraindications to low-Vt ventilation, and perceived process barriers (7, 8). In contrast, this study demonstrates that clinicians believe low-Vt ventilation should be used for their patients and do not identify significant barriers to its use; yet, they do not initiate it. Also, the lack of correlation between attitudes and practice suggests that a knowledge deficit is not the likely barrier to low-Vt ventilation use. These findings strongly suggest that other factors are at play.

Consistent with previous researchers, we believe that these factors fall into several other categories, including inappropriate ARDSNet low-Vt ventilation strategies and unperceived process barriers (8, 20). Inappropriate ARDSNet low-Vt ventilation strategies may include using actual body weight for Vt selection instead of calculating PBW, basing ventilation decisions on plateau pressure instead of initially administering low-Vt ventilation, or believing that a higher Vt (e.g., <8 ml/kg PBW) constitutes low-Vt ventilation. Unperceived process barriers may include reluctance among RTs and/or nurses to initiate low-Vt ventilation despite a physician’s order (e.g., due to concerns about patient comfort), leading to a physician’s thinking it is being delivered when it is not; low staffing ratios for managing patients with ARDS (7, 8); or role ambiguity, whereby clinician groups may not believe they have primary responsibility for ensuring low-Vt ventilation. One potential barrier, failing to recognize ARDS, could be due to not knowing the ARDS diagnostic criteria and an unperceived process barrier (not receiving the data needed to make the diagnosis). Although we did not assess ARDS recognition, the researchers in the multinational Large observational study to UNderstand the Global impact of Severe Acute respiratory FailurE (LUNG SAFE) study found that ARDS was underrecognized across 459 ICUs in 50 countries (20). Studies in which researchers investigate potential barriers in the context of observed low-Vt ventilation delivery may be useful for understanding the role these barriers play in the actual delivery of low-Vt ventilation.

These potential barriers support the development of specific interventions—audit and feedback, clinician education, and clinical decision support to improve the recognition of ARDS (e.g., prompting or reminders) and overcome process barriers to the delivery of low-Vt ventilation. However, recent studies whose aim was to improve identification of or provide clinical decision support for ARDS, as well as sepsis, have shown mixed results in improving processes or patient outcomes (21–27), suggesting an urgent need for more investigation in this area.

Our study extends the existing literature in several ways. First, to our knowledge, our study is the first to contrast a broad range of front-line physician, nurse, and RT attitudes and perceived performance with observed use of low-Vt ventilation. By initially distributing the survey 10 months after the ARDS cohort was developed, we ensured that the clinicians who cared for the ARDS cohort and those who received the survey were mostly overlapping (for physicians, completely overlapping), while avoiding the risk of bias had the survey been rolled out as performance was being measured. Our findings are consistent with those from a previous study in which researchers surveyed ICU directors only. The authors of that report of ICU director–perceived use versus observed use of low-Vt ventilation found a discrepancy of 79.9% perceived use versus 2.6% observed use (28). Physician overestimation of clinical performance has been observed in several medical specialties (29–32). Furthermore, the rate of low-Vt ventilation initiation in this study is lower than low-Vt ventilation use in the LUNG SAFE study, which could be due to the geographic limitation of our study or a result of the specific training and prompting of LUNG SAFE clinicians to consider a diagnosis of ARDS, interventions that could increase ARDS recognition and lead to increased low-Vt ventilation initiation (20).

Second, we performed a sensitivity analysis using the higher Vt threshold of 8 ml/kg PBW, increasing the robustness of our comparison of perceived versus observed low-Vt ventilation use. Third, this study contained a larger sample size than previous similar studies, included both academic and community hospitals in socioeconomically diverse areas, and had a high response rate. Fourth, by not including ARDSNet sites, our results are more generalizable to the broad practice of critical care medicine, removed from the network that developed low-Vt ventilation (8). Fifth, we made direct comparisons between physicians, nurses, and RTs, reinforcing a previous study in which researchers found fewer attitudinal and perceived process barriers to low-Vt ventilation among physicians than among nurses or RTs (8). Finally, by not being accompanied by an ARDS-specific or low-Vt ventilation–specific intervention—such as a low-Vt ventilation protocol or an intervention that primes clinicians to look for ARDS—our results are not biased by the presence of strategies that simultaneously attempt to improve low-Vt ventilation use (8, 20).

Our study has several limitations. First, the clinicians in our study practice in a single geographic region, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, although response rates were high, it is possible that responders differed from nonresponders, which could bias our findings. Third, nurse and RT use data were available at only two hospitals (albeit representing >80% of the ARDS patient cohort), and identification of the primary nurse and RT was potentially more prone to error compared with physician identification. Fourth, interpretation of nurse results may be limited because of differences in age and years in practice between nurse survey responders with and without use data. Fifth, we did not assess whether role ambiguity—each group of clinicians not understanding who had primary responsibility to deliver low-Vt ventilation, thus resulting in none of the groups taking this responsibility—may be a process barrier. Finally, not explicitly defining low-Vt ventilation or assessing clinicians’ knowledge of what constitutes low-Vt ventilation could affect the comparison of perceived versus observed performance because clinicians may have a different understanding of what constitutes low-Vt ventilation (e.g., believing a Vt <8 ml/kg PBW constitutes low-Vt ventilation). However, we demonstrated that a median of only 16.7% of patients cared for by attending physician survey responders were initiated on a Vt less than 8 ml/kg PBW, and this higher Vt threshold was not significantly correlated with attitudes or perceived process barriers. The two questions that were negatively correlated with initiation of Vt less than 8 ml/kg PBW could be a result of physicians who are more likely to use this Vt being more aware of potential barriers such as ease of ordering or the time it takes to diagnose ARDS. In general, however, there is still a wide discrepancy between perceived performance and low-Vt ventilation use at this higher Vt threshold.

In summary, in a large multihospital survey of critical care physicians, nurses, and RTs, clinicians had positive attitudes toward low-Vt ventilation use, and they did not perceive significant barriers to its use for patients with ARDS. Although clinicians believed that the great majority of their patients with ARDS warranted treatment with low-Vt ventilation, they initiated it for less than 1 in 10 patients. These results suggest that barriers to low-Vt ventilation use other than negative attitudes or perceived barriers exist. Implementation strategies should be focused on examining other issues, such as ARDS recognition and process solutions, to improve low-Vt ventilation use.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K23HL118139) (C.H.W.); a grant from the Francis Family Foundation (Parker B. Francis Fellowship) (C.H.W.); the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Enterprise Data Warehouse, which is supported by a grant (8 UL1TR000150) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; and the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the U.S. Army Research Office (W911NF-14-1-0259) (C.H.W. and M.B.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Francis Family Foundation.

Author Contributions: Conception or design: C.H.W., D.W.B., M.B., A.R., R.G.W., and S.D.P.; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: C.H.W., D.W.B., K.T., S.W., M.B., A.R., A.F., R.G.W., S.D.P.; drafting of the manuscript: C.H.W.; revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: C.H.W., D.W.B., K.T., S.W., M.B., A.R., A.F., R.G.W., S.D.P.; final approval of the manuscript for submission: C.H.W., D.W.B., K.T., S.W., M.B., A.R., A.F., R.G.W., S.D.P.; and accountable for all aspects of work: C.H.W., D.W.B., K.T., S.W., M.B., A.R., A.F., R.G.W., S.D.P.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Needham DM, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Dinglas VD, Sevransky JE, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, Desai SV, Shanholtz C, Brower RG, Pronovost PJ. Lung protective mechanical ventilation and two year survival in patients with acute lung injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e2124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Needham DM, Yang T, Dinglas VD, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Sevransky JE, Brower RG, Pronovost PJ, Colantuoni E. Timing of low tidal volume ventilation and intensive care unit mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:177–185. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1598OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubenfeld GD, Cooper C, Carter G, Thompson BT, Hudson LD. Barriers to providing lung-protective ventilation to patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1289–1293. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127266.39560.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennison CR, Mendez-Tellez PA, Wang W, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Barriers to low tidal volume ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome: survey development, validation, and results. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2747–2754. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000287591.09487.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss CH, Baker DW, Weiner S, Bechel M, Ragland M, Rademaker A, Weitner BB, Agrawal A, Wunderink RG, Persell SD. Low tidal volume ventilation use in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1515–1522. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, Thomason JW, Schweickert WD, Pun BT, Taichman DB, Dunn JG, Pohlman AS, Kinniry PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:126–134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yousefi-Nooraie R, Dobbins M, Brouwers M, Wakefield P. Information seeking for making evidence-informed decisions: a social network analysis on the staff of a public health department in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:118. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousefi-Nooraie R, Dobbins M, Marin A. Social and organizational factors affecting implementation of evidence-informed practice in a public health department in Ontario: a network modelling approach. Implement Sci. 2014;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melas CD, Zampetakis LA, Dimopoulou A, Moustakis V. Evaluating the properties of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS) in health care. Psychol Assess. 2012;24:867–876. doi: 10.1037/a0027445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS) Ment Health Serv Res. 2004;6:61–74. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000024351.12294.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SurveyMonkey. [Accessed 2016 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.surveymonkey.com/

- 18.Checkley W, Brower R, Korpak A, Thompson BT Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network Investigators. Effects of a clinical trial on mechanical ventilation practices in patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1215–1222. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1424OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hager DN, Krishnan JA, Hayden DL, Brower RG ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Tidal volume reduction in patients with acute lung injury when plateau pressures are not high. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1241–1245. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200501-048CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, et al. LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fröhlich S, Murphy N, Doolan A, Ryan O, Boylan J. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: underrecognition by clinicians. J Crit Care. 2013;28:663–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourdeaux CP, Thomas MJ, Gould TH, Malhotra G, Jarvstad A, Jones T, Gilchrist ID. Increasing compliance with low tidal volume ventilation in the ICU with two nudge-based interventions: evaluation through intervention time-series analyses. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010129. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bagga S, Paluzzi DE, Chen CY, Riggio JM, Nagaraja M, Marik PE, Baram M. Better ventilator settings using a computerized clinical tool. Respir Care. 2014;59:1172–1177. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manaktala S, Claypool SR. Evaluating the impact of a computerized surveillance algorithm and decision support system on sepsis mortality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24:88–95. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semler MW, Weavind L, Hooper MH, Rice TW, Gowda SS, Nadas A, Song Y, Martin JB, Bernard GR, Wheeler AP. An electronic tool for the evaluation and treatment of sepsis in the ICU: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1595–1602. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper MH, Weavind L, Wheeler AP, Martin JB, Gowda SS, Semler MW, Hayes RM, Albert DW, Deane NB, Nian H, et al. Randomized trial of automated, electronic monitoring to facilitate early detection of sepsis in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2096–2101. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318250a887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Churpek MM, Zadravecz FJ, Winslow C, Howell MD, Edelson DP. Incidence and prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and organ dysfunctions in ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:958–964. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0275OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Ragaller M, Welte T, Rossaint R, Gerlach H, Mayer K, John S, Stuber F, Weiler N, et al. German Sepsis Competence Network (SepNet) Practice and perception—a nationwide survey of therapy habits in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2719–2725. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186b6f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephenson JJ, Tunceli O, Gu T, Eisenberg D, Panish J, Crivera C, Dirani R. Adherence to oral second-generation antipsychotic medications in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: physicians’ perceptions of adherence vs. pharmacy claims. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:565–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02918.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CB, Cox M, Olson DM, Britz GW, Constable M, Fonarow GC, Schwamm L, Peterson ED, Shah BR. Perception versus actual performance in timely tissue plasminogen activation administration in the management of acute ischemic stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001298. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oderda GM, Shiozawa A, Walsh M, Hess K, Brixner DI, Feehan M, Akhras K. Physician adherence to ACR gout treatment guidelines: perception versus practice. Postgrad Med. 2014;126:257–267. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2014.05.2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chant C, Dos Santos CC, Saccucci P, Smith OM, Marshall JC, Friedrich JO. Discordance between perception and treatment practices associated with intensive care unit-acquired bacteriuria and funguria: a Canadian physician survey. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1158–1167. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181692af9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.