Abstract

Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor are frequent in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer but less so in patients with localized disease, and patients who have Li–Fraumeni with germline p53 mutations do not have an increased incidence of prostate cancer, suggesting that additional molecular and/or genetic changes are required for p53 to promote prostate carcinogenesis. ELL-associated factor 2 (EAF2) is a tumor suppressor that is frequently downregulated in advanced prostate cancer. Previous studies have suggested that p53 binds to EAF2, providing a potential mechanism for their functional interactions. In this study, we tested whether p53 and EAF2 could functionally interact in prostate cancer cells and whether concurrent inactivation of p53 and EAF2 could promote prostate carcinogenesis in a murine knockout model. Endogenous p53 coprecipitated with EAF2 in prostate cancer cells, and deletion mutagenesis indicated that this interaction was mediated through the C terminus of EAF2 and the DNA binding domain of p53. Concurrent knockdown of p53 and EAF2 induced an increase in proliferation and migration in cultured prostate cancer cells, and conventional p53 and EAF2 knockout mice developed prostate cancer. In human prostate cancer specimens, concurrent p53 nuclear staining and EAF2 downregulation was associated with high Gleason score. These findings suggest that EAF2 and p53 functionally interact in prostate tumor suppression and that simultaneous inactivation of EAF2 and p53 can drive prostate carcinogenesis.

In vitro cell line studies and conventional deletion of EAF2 and p53 in a murine model demonstrate their functional interaction in prostate tumor suppression.

Prostate carcinogenesis is a multistep process involving alteration and loss of function in multiple tumor suppressors. One of the most well-known tumor suppressors is p53. The p53 gene is particularly subject to missense mutations [reviewed in Olivier et al. (1)] in which the p53 protein loses the ability to bind DNA and activate transcription of p53 target genes (2). Wild-type p53 protein functions to facilitate cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis in response to DNA damage and other stress signals, whereas mutated p53 can result in the continued replication of damaged cells. Mutations in p53 are less common in localized prostate tumors but are frequently reported in advanced disease, particularly in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (3–7). Patients who have Li–Fraumeni with germline p53 mutations do not have an increased incidence of prostate cancer, which also suggests that p53 has a limited role in early prostate tumorigenesis (8–10). Several studies have reported that p53 overexpression/mutation in combination with mutations in other tumor suppressors is associated with poor prognosis and disease recurrence in prostate cancer [reviewed in (11)]. Tumor formation in mice with conventional p53 deletion has been described in detail (12–14). Briefly, p53 deficiency is not critical for embryonic and postnatal development. The most common tumor types in p53+/− mice are sarcoma in 57% and lymphoma in 25% of animals (12). The predominant tumor type in p53−/− is lymphoma (71%), particularly in the thymus (12). Tumor latency and life span in p53−/− is significantly shorter than in p53+/− mice (12). There has been no reported prostate phenotype in mice with conventional p53 deletion (12–14). Prostate-specific deletion of p53 also displayed no phenotype up to 18 months of age (15), but was reported to induce murine prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (mPIN) in mice at 600 days of age (16). Tissue recombinants of p53-deficient adult prostatic epithelium and embryonic rat seminal vesicle mesenchyme resulted in nuclear atypia (17). Although p53 deletion alone has not definitively been shown to initiate prostate carcinogenesis in murine models, it has been shown to accelerate tumorigenesis when combined with the deletion of other tumor suppressors (15, 16, 18).

ELL-associated factor 2 (EAF2) is an androgen-responsive tumor suppressor that is frequently downregulated in advanced prostate cancer (19, 20). Overexpression of EAF2 in prostate cancer cells can induce apoptosis and growth inhibition in cultured cells as well as in tumor xenografts (21). Knockdown of EAF2 in prostate cancer cells induced proliferation and enhanced migration (22), and Eaf2−/− mice developed mPIN lesions characterized by increased vascularity and a stromal response (19, 23). However, these lesions did not progress to prostate cancer (19, 24). We recently examined the role of EAF2 loss in conjunction with PTEN heterozygosity on prostate tumor formation in mice (25). In these mice, 33% developed spontaneous prostate tumors accompanied by increased vascularity and proliferation by the age of 12 months, indicating that EAF2 could cooperate with other tumor suppressors in suppressing tumor development (25).

Our recent study suggested interactions between EAF2 and p53 (26). EAF2 and p53 colocalize, coimmunoprecipitate, and cooperate in growth suppression when cotransfected in prostate cancer cell lines (26). Because both p53 and EAF2 play important roles in prostate carcinogenesis, we investigated the significance of their interactions in prostate carcinogenesis by assessing the impact of Eaf2 loss in p53-deficient mice and concurrent knockdown of EAF2 and p53 in cultured C4-2 human prostate cancer cells as well as immunostaining analysis in human prostate cancer specimens.

Materials and Methods

Construction of plasmids

Full-length complementary DNA of human EAF2 and human p53 were subcloned into pCMV-Myc or pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) vector to generate p-CMV-Myc-EAF2 and pEGFP-C1-p53 as previously described (26). EAF2 deletion mutants were generated previously (27), and p53 deletion mutants were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and verified by sequencing.

5-Bromo-2'-deoxyuridine assay

C4-2 cells seeded on coverslips were treated with 2 nM R1881 for 48 hours following RNA interference. Cells were subsequently cultured in the presence of 10 μM 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) for 2 hours and then fixed with Carnoy fixative (3:1 volume-to-volume methanol and glacial acetic acid) for 20 minutes at −20°C. After treatment with 2 M HCl and 0.1 M boric acid, cells were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes at room temperature, followed by blocking with 10% goat serum for 1 hour. Cells were then incubated with anti-BrdU antibody (Table 1) overnight at 4°C and CY3-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (catalog no. A10521; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hour at 37°C. The nucleus was stained with SYTOX Green (catalog no. S7020; Life Technologies). Images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon TE2000-U; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Cells were counted using the Photoshop CS5 counting tool (Adobe, San Jose, CA) or Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD), and the number of BrdU-positive cells was assessed as percentage of the total cell number by counting the total number of BrdU-positive cells in at least five nonoverlapping fields for each condition at ×40 magnification.

Table 1.

Antibodies Used for Western Blot, Immunofluorescence, and Immunohistochemical Staining

| Antibody | Source | Clone, Catalog No. | RRID | Species Raised in; Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Application, Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrdU | Sigma-Aldrich | B2531 | AB_476793 | Mouse; monoclonal | IF, 1:300 |

| p53 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | FL393 | AB_653753 | Rabbit; polyclonal | WB, 1:500 |

| p53 Ab-8 | Thermo Scientific | DO-7+BP53-12 | AB_141727 | Mouse; monoclonal | IHC, 1:100 |

| EAF2 | Pascal et al. (23) | AB_2714014 | Mouse; monoclonal | WB, 1:5000 IHC, 1:500 | |

| STAT3 | Cell Signaling | 79D7, 4904 | AB_331269 | Rabbit; monoclonal | WB, 1:6000 |

| p-STAT3 (Tyr705) | Cell Signaling | D3A7, 9145 | AB_2491009 | Rabbit; monoclonal | WB, 1:500 IHC, 1:10 |

| GFP-agarose | Medical and Biological Laboratories | D153-8 | AB_591815 | Rat; monoclonal | WB, 1:5000 |

| GFP | Torrey Pines Biolabs | ABIN110592 | AB_10013661 | Rabbit; polyclonal | WB, 1:6000 |

| Lamin A/C | GenScript | A01455-40 | AB_1720882 | Rabbit; polyclonal | WB, 1:1000 |

| Anti-c-Myc-agarose | Sigma-Aldrich | A7470 | AB_10109522 | Rabbit; polyclonal | WB, 1:3000 |

| Myc | Covance | 9E10 | AB_291323 | Mouse; monoclonal | WB, 1:3000 |

| GAPDH | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | FL-335, sc25778 | AB_10167668 | Rabbit; polyclonal | WB, 1:8000 |

| CD31 | BD Biosciences | MEC 13.3, 550274 | AB_393571 | Rat; monoclonal | IHC, 1:400 |

| Ki-67 | Dako | TEC-3, M7249 | AB_2250503 | Rat; monoclonal | IHC, 1:400 |

| p63 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | 4A4, sc8431 | AB_628091 | Mouse; monoclonal | IHC, 1:400 |

| CK18 [C-04] | Abcam | ab-668 | AB_305647 | Mouse; monoclonal | IHC, 1:20 |

| Tenascin-C | Chemicon | AB19013 | AB_2256033 | Rabbit; polyclonal | IHC, 1:20 |

| Synaptophysin | BD Biosciences | BD-611880 | AB_399360 | Mouse; monoclonal | IHC, 1:20 |

Abbreviations: IF, immunofluorescence; IHC, immunohistochemistry; RRID, Research Resource Identifier; WB, western blot.

Wound healing and transwell migration assays

The wound healing assay was performed in a six-well plate. Following RNA interference, C4-2 cells were treated with 2 nM R1881 for 48 hours until they reached a density of ∼70%. Straight scratches were made using a 200-μL pipette tip. Debris was removed by washing the cells with phosphate-buffered saline, and 2 mL of fresh medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added. Cells were incubated at 5% CO2 and 37°C for 24 hours. Images were taken using brightfield microscopy (TS100; Nikon) at 0, 12, and 24 hours. Cell proliferation was normalized as a percentage of the initial cell number at time 0. Cells were harvested and counted with a hemocytometer at time 0, 12, and 24 hours and results were plotted on a linear scale as a percentage of the initial cell number at time 0. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated a minimum of three times. Quantification of gap closure was also normalized to the initial gap size, and results were plotted as a percentage of the initial gap size at time 0. Cell migration was studied using a haptotactic migration assay. C4-2 cells were transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) at 100 pmol each for EAF2, p53, and combined EAF2 and p53 in a six-well plate for 48 hours, collected with trypsin treatment, resuspended in 200 μL of RPMI 1640/0.2% bovine serum albumin at 1 × 104 cells, and then placed into the top chamber of a transwell chamber (24-well, 8-μm pore size; Corning, Corning, NY). The bottom chamber contained 10% FBS as chemoattractant. After 36 hours, nonmigrating cells on the top surface of the chamber membrane were gently removed with a cotton swab. The cells that migrated to the opposite side of the membrane were fixed stained with 0.1% crystal violet and counted in five random optical fields (×400 magnification) using brightfield microscopy.

Generation of EAF2 and p53 gene deletion mice

Preparation of mice with specific deletion of the Eaf2 or p53 genes has been described previously (19, 26, 28). Heterozygous Eaf2 mice on a C57BL6/J background were crossed with heterozygous p53 mice (catalog no. 002101; B6.129S2-Trp53tm1Tyj/J; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and these mice were again intercrossed to generate various cohorts with either p53−/−, p53+/−, or p53+/+ background (Supplemental Fig. 1A (931.7KB, TIF) ). Genotyping was performed using PCR analysis of mouse tail genomic DNA at age 21 days and after euthanization (Supplemental Fig. 1B (931.7KB, TIF) ) (19, 28). All mice were maintained identically, under approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh.

Histopathologic analysis

Samples were fixed in 10% formalin for at least 24 hours, then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. All tissues were examined and scored by a board-certified animal pathologist in a blinded fashion (L.H.R., V.M.D). Lesions were identified as mPIN and prostate cancer per the criteria published by Shappell et al. (29) commonly used to score prostate lesions in transgenic mouse models. mPIN were dysplastic lesions that appeared mainly as cribriform structures along with occasional stratification of cells, papilliferous structures, and tufts of cells (29). These lesions may fill and expand the glandular lumen, but they did not invade the basement membrane. Prostate cancer lesions were characterized by a loss of basal cells (30). Prostate cancer lesions were unencapsulated, often poorly circumscribed, and comprised of haphazard acini and lobules of pleomorphic cells with no or limited amounts of fibrovascular stroma (29). They may also be arranged in solid sheets of cells. Necrosis, vascular invasion, and/or local invasion of the tumor beyond the basement membrane into surrounding stromal tissues may be observed (29).

Cell culture, transfection, and RNA interference

The prostate cancer cell line C4-2 was a gift from Dr. Leland W.K. Chung, and the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP and the human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cell line were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). C4-2 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium, and HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM medium. All media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Cell lines C4-2 and LNCaP were authenticated in 2016 using DNA fingerprinting by examining microsatellite loci in a multiplex PCR reaction (AmpFlSTR Identifiler PCR amplification kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by the University of Pittsburgh Cell Culture and Cytogenetics Facility. The HEK293 cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection in 2016. The American Type Culture Collection performed authentication for the HEK293 cell line using short tandem repeat profiling. For overexpression experiments, cells were transfected with plasmids using PolyJet in vitro transfection reagent (SignaGen Laboratories, Rockville, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for 48 hours. Cells were then harvested and prepared for subsequent assays. For knockdown experiments, cells were transfected with 100 pmol nontargeted siRNA or siRNA against p53 and EAF2 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a six-well plate. Targeted siRNA was complemented with nontargeted siRNA in the single knockdown group such that the total amount of siRNAs in each well was identical. At 24 hours posttransfection, cells were treated with 2 nM R1881 for an additional 48 hours and then used for further experiments. Nontargeted control siRNA (sc-37007, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) as well as targeted siRNA against EAF2 and p53 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) were used. Pooled siRNA against p53 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-29435); siRNA against EAF2 was designed using the Integrated DNA Technologies RNA interference design tool (31) as follows: 5′-AAACAGUUACUGGUGGAGUUGAACCUU-3′ (Integrated DNA Technologies). Additional siRNA sequences for validation experiments were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies and included sip53 no. 2 (5′-AGUGUUUCUGUCAUCCAAAUACUCCAC-3′) and siEAF2 no. 2 (5′-CUGUUCACCUUCACCAACCUCAAGGUA-3′).

Coimmunoprecipitation

HEK293 cells were transfected with indicated plasmids, cultured for 48 hours, and then lysed in RIPA lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, and 0.25% sodium deoxycholate (pH 7.8)]. After preclearing with protein A/G Plus–agarose beads (catalog no. sc-2003; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 hours, cell lysates were mixed with anti-GFP or Myc antibody-conjugated agarose beads (Table 1) and rotated for 2 hours at 4°C. Then beads were washed with lysis buffer five times. Finally, immunoprecipitates and whole-cell lysate were boiled with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample loading buffer for 10 minutes and then subjected to western blot analysis.

For coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous EAF2 and p53, C4-2 cells were treated with control siRNA or p53 siRNA for 48 hours and treated with 1 nM R1881 for 24 hours. DNA damage was induced by treatment of cells with 1.0 μg/mL doxorubicin for 6 hours. Nuclear extracts (NEs) were immunoprecipitated with immobilized anti-p53 (FL-393). Specifically, 100 to 150 μL of NE at 0.5 μg/μL and 5 μg of conjugated anti-p53 antibody were gently mixed and rotated at 4°C for 1 hour, then centrifuged at 5000 × g for 3 minutes at 4°C to remove NEs. The pelleted anti-p53 beads were then added with 100 to 150 μL of fresh NE to repeat immunoprecipitation, which was repeated three to four times. The pelleted beads were then washed with 800 μL of lysis buffer for 3 minutes at 4°C for a total of five times. Protein expression was analyzed by western blot.

Western blot

Cell samples were lysed in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (volume-to-volume) Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 1:100 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail; catalog no. P8340, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO], and protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Tissue lysate was boiled with SDS sample buffer, separated on a NEXT GEL 10% gel (Amresco, Dallas, TX) under reducing conditions, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Blotted proteins were probed with primary antibodies (Table 1) followed by horseradish peroxidase–labeled secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Signals were visualized using chemiluminescence (ECL western blotting detection reagents; GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) and exposed to X-ray film (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Human prostate tissue specimens

Human prostate tissue specimens without any previous chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy were obtained from the surgical pathology archives of the University of Pittsburgh Prostate Tumor Bank under approval by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board from de-identified tumor specimens consented for research at time of treatment. Specimens included nine matched prostate cancer and benign prostate specimens adjacent to prostate cancer as well as two tissue microarray (TMA) slides. TMA specimens scored included 104 normal prostate specimens adjacent to malignant glands plus 16 normal donor prostate specimens, 64 high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia specimens, and 216 acinar type specimens of prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemical staining

The methods of tissue collection and immunostaining have been published previously (19). Briefly, tissues were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin at 4°C overnight. Samples were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Slides were then counterstained in hematoxylin and coverslipped. Immunostained sections (antibodies listed in Table 1) were imaged with a Leica DM LB microscope (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) equipped with a QImaging MicroPublisher 3.3 RTV digital camera (QImaging, Surry, BC, Canada). All tissues were examined by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (L.H.R.) or a board-certified genitourinary pathologist (A.V.P.) using light microscopy. Immunostained sections were imaged with a Leica LMD6000 microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc.) equipped with a Hitachi 3-CCD HV-D20P digital camera (Hitachi Kokusai Electric Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and Leica Laser Microdissection version 6.3 software.

Immunostaining image analysis

Slides stained with EAF2 and p53 were evaluated semiquantitatively. The percentage of prostate epithelial cells in each core that expressed the antigen was estimated at a final magnification of ×40. Protein expression was assessed as a function of staining intensity and percentage of cells exhibiting each level of intensity. The intensity of the reaction product was based on a four-point scale: none, faint/equivocal, moderate, and intense. An H score was calculated for each immunostain by cell type using the following formula: H score = 0 (% no stain) + 1 (% faint/equivocal) + 2 (% moderate) + 3 (% intense).

Statistical analysis

Comparison between groups was calculated using a Student t test. The Kaplan–Meier test was used to calculate survival, and the log-rank test was used for evaluation of significance in the murine knockout model. The two-tailed Fisher exact test was used to determine whether tumor frequency differed between animal cohorts and whether alteration frequency differed between prostate tissue specimens. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. GraphPad Prism version 4 was used for graphics (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Endogenous coimmunoprecipitation of EAF2 and p53

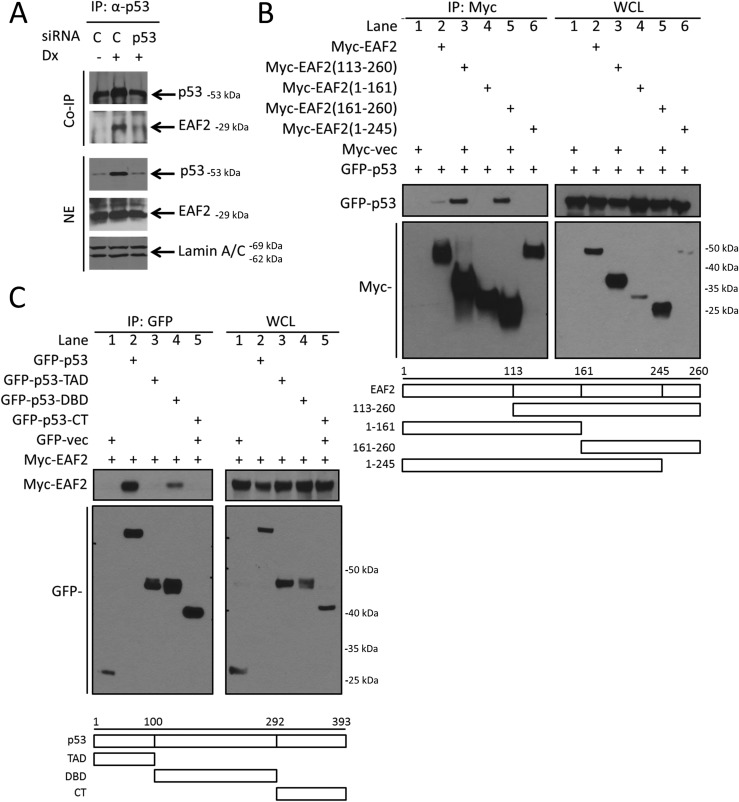

Epitope-tagged EAF2 was shown previously to coimmunoprecipitate with p53 in transiently transfected HEK293 cells (26). To further evaluate the physiological relevance of this finding in prostate cancer, coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous p53 and EAF2 using an anti-p53 antibody in C4-2 prostate cancer cells was performed (Fig. 1A). DNA damage induced by doxorubicin increased p53 protein level and EAF2 coprecipitation, whereas siRNA knockdown of p53 significantly inhibited the coprecipitation of EAF2 protein, suggesting that endogenous EAF2 and p53 are present in the same protein complex in prostate cancer cells.

Figure 1.

In vivo association and domain mapping of p53 and EAF2 protein interactions. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of p53 with EAF2 in C4-2 cells treated with sip53 in C4-2 cells in the presence and absence of DNA damage induced by 1.0 μg/mL doxorubicin (Dx) for 6 hours. NEs were immunoprecipitated with immobilized anti-p53. Proteins were immunoblotted with anti-p53 and anti-EAF2. Lamin A/C served as loading control of nuclear proteins. (B) Domain mapping of the interaction between EAF2 and p53. GFP-p53 was cotransfected with Myc-tagged EAF2 deletion mutants (amino acids 113 to 260, 1 to 161, 161 to 260, and 1 to 245) into HEK293 cells. Myc-vec was added as a control plasmid to equalize the amount of transfection reagents for all cells to 2.5 μg total. (C) Myc-EAF2 was cotransfected with GFP-tagged p53 deletion mutants [1 to 100, transcription activation domain (TAD); 100 to 292, DBD; and 292 to 393, C-terminal domain (CT)] into HEK293 cells. GFP-vec was added as a control plasmid to equalize the amount of transfection reagents for all cells to 2.5 μg total. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) were immunoprecipitated with anti-MYC or anti-GFP–conjugated agarose beads, and blots were probed with (B) anti-Myc or (C) anti-GFP antibody.

Deletion mutagenesis followed by coimmunoprecipitation was performed to determine the regions required for EAF2 binding to p53 in HEK293 cells. The EAF2 fragment containing amino acids 1 to 245 was unable to bind to GFP-p53 (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the amino acids 245 to 260 of the C-terminal portion of EAF2 was essential for its interaction with p53. The EAF2 fragment amino acids 1 to 161 had reduced binding to GFP-p53 compared with full-length Myc-EAF2, potentially due to conformational changes that might inhibit but not prevent efficient EAF2 and p53 binding. Although coprecipitation of p53 by EAF2 was weak in this experiment (see Fig. 1B, lane 2), the coprecipitation was reproducible and indicated the interaction between full-length EAF2 and GFP-p53. Mutation analysis with p53 demonstrated that the DNA binding domain (DBD) of p53 containing amino acids 100 to 292 was required for interaction with EAF2 (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that the interaction is mediated through the C terminus of EAF2 and the DBD of p53.

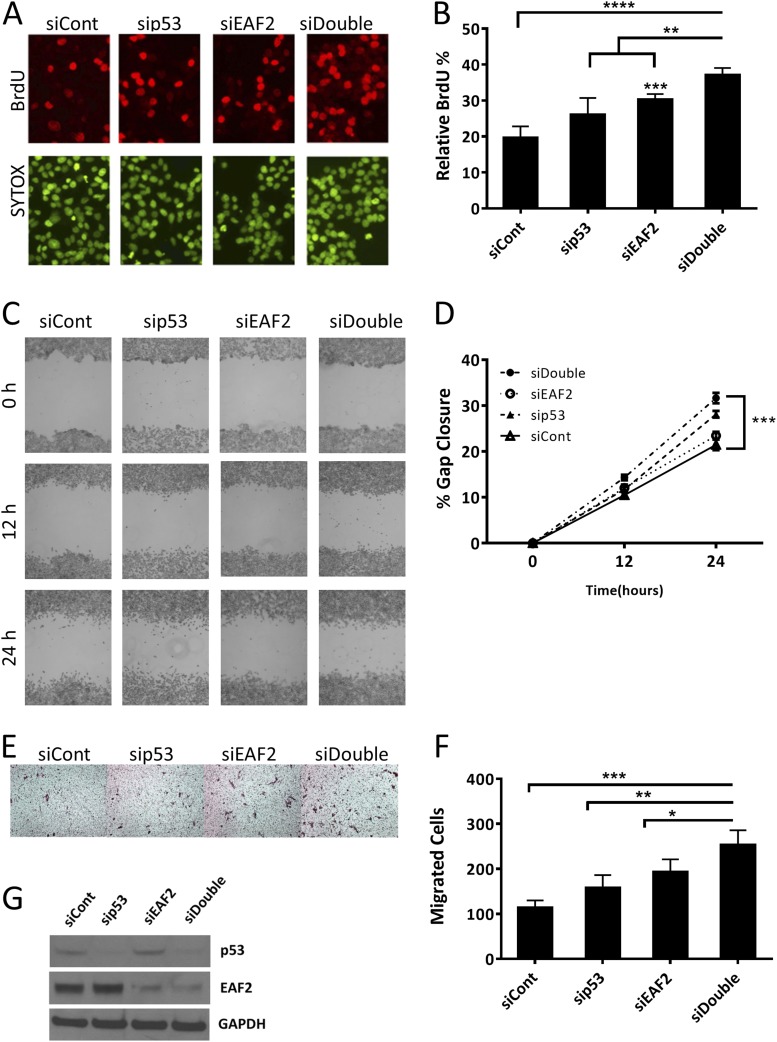

Combined knockdown of EAF2 and p53 promotes cell proliferation and migration

C4-2 cells were transfected with siRNAs against EAF2 and/or p53 (Fig. 2). Knockdown of p53 alone induced a moderate, nonsignificant increase in proliferation (P = 0.07) similar to that previously reported for LNCaP cells (32). Paralleling our previous results (22), single knockdown of EAF2 in C4-2 cells increased cell proliferation as evidenced by increased BrdU uptake (Fig. 2A and 2B). Moreover, proliferation was further enhanced after combined transfection with siRNA against EAF2 and p53 as indicated by a significant increase in BrdU uptake in double compared with single knockdown cells. These results indicated that EAF2 and p53 were both functionally significant in the modulation of cellular proliferation in prostate cancer cells. Both the wound healing scratch assay and haptotactic migration assay confirmed that C4-2 cell migration was significantly enhanced after knockdown of p53 or EAF2. Combined knockdown of EAF2 and p53 significantly increased gap closure as well as transwell migration compared with individual knockdown of either EAF2 or p53 (Fig. 2C–2F). Similar effects on proliferation and migration were achieved when we targeted EAF2 and p53 with different siRNA sequences, excluding potential nonspecific siRNA effects (Supplemental Fig. 2 (1.8MB, TIF) ). LNCaP cells transfected with siRNAs against EAF2 and/or p53 also induced similar increased BrdU uptake and wound healing (Supplemental Fig. 3 (2MB, TIF) ). Normalization of the number of C4-2 and LNCaP cells for double EAF2 and p53 knockdown compared with control cells was performed to ensure that cell proliferation did not impact wound healing or migration (Supplemental Fig. 4 (587.3KB, TIF) ). These results suggest that p53 and EAF2 cooperate to suppress tumor growth and motility in cultured prostate cancer cells and that their combined loss may act to promote prostate carcinogenesis.

Figure 2.

Cell proliferation and migration in EAF2- and p53-deficient C4-2 cells. (A) BrdU incorporation in C4-2 cells transfected with nontargeted control (siCont) siRNA, targeted to p53 (sip53), EAF2 (siEAF2), or concurrent EAF2 and p53 (siDouble) knockdown. The upper panel shows BrdU-positive nuclei (red), and the lower panel shows nuclear staining with SYTOX Green (green). Original magnification, ×40. (B) Quantification of BrdU incorporation shown as mean percentage ± standard deviation of BrdU-positive cells relative to the total number of cells (at least 400 total cells were counted for each condition). Results for (A) and (B) are representative of four individual experiments. (C) Wound healing assay in C4-2 cells following siRNA knockdown as in (A). Cells were imaged at 0, 12, and 24 hours after treatment and gap widths were measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Original magnification, ×10. (D) Quantification of gap closure shown as the mean percentage ± standard error of the mean of initial gap and are representative of three individual experiments. (E) Haptotactic transwell migration assay in C4-2 cells following siRNA knockdown as in (A), after 24 hours with 10% FBS as chemoattractant. Original magnification, ×20. (F) Quantification of migrated cells. Results for (E) and (F) are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and are representative of three individual experiments. (G) Western blot analysis of EAF2 and p53 protein from C4-2 cell lysates following siRNA knockdown as in (A). Cells were grown in 2 nM R1881 48 hours prior to harvest to induce detectable levels of EAF2 expression. GAPDH served as internal loading control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

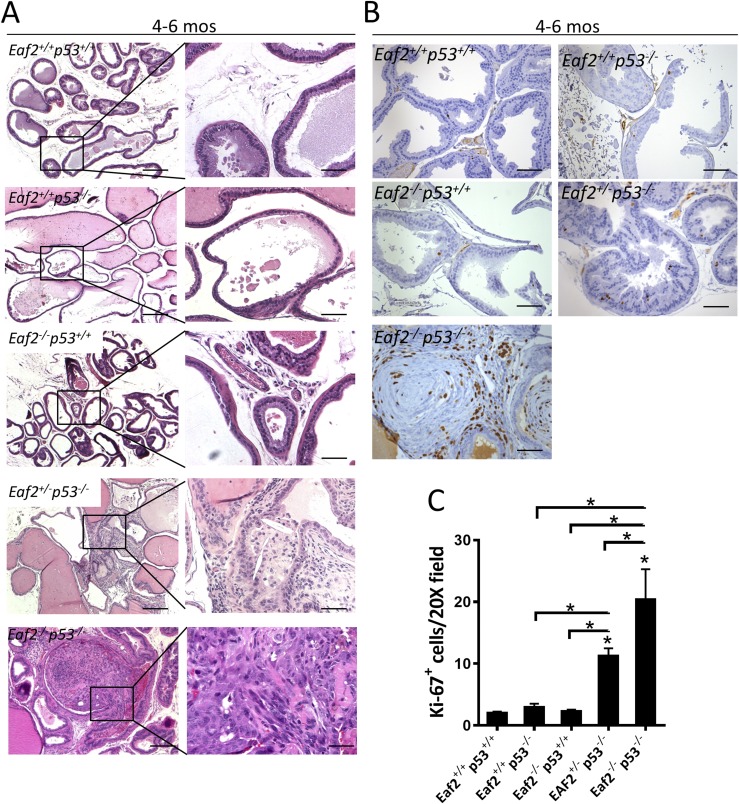

Prostate intraepithelial neoplasia and adenocarcinoma in Eaf2- and p53-deficient mice

To determine the potential impact of concurrent EAF2 and p53 loss on prostate carcinogenesis in vivo, we generated Eaf2-deficient mice on either a p53−/− or p53+/− background (Supplemental Fig. 1 (931.7KB, TIF) ). Because Eaf2 loss on the C57BL/6J background induced mPIN lesions but not tumors in other major organs (23), the C57BL/6J Eaf2−/− strain was used. Mice were evaluated twice weekly for signs of morbidity or tumor growth: when animals appeared distressed, they were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and full necropsy was performed. Animals on a p53−/− background included Eaf2+/+p53−/−, Eaf2+/−p53−/−, and Eaf2−/−p53−/−; animals on a p53+/− background included Eaf2+/+p53+/−, Eaf2+/−p53+/−, and Eaf2−/−p53+/−. Similar to other studies, thymic lymphomas comprised most of the tumors observed in p53−/− mice and were the predominant cause of the significantly increased mortality observed in p53−/− compared with p53+/− cohorts, irrespective of Eaf2 status. Overall survival of p53−/− or p53+/− control mice was not significantly impacted by Eaf2 status (Supplemental Fig. 1C (931.7KB, TIF) ), likely due to the lack of tumor induction in nonprostate tissues by Eaf2 deletion.

As previously reported, female p53−/− mice were present in lower numbers than expected (33, 34), and this was also true of female Eaf2+/− and Eaf2−/− mice on a p53−/− background. Interestingly, although female Eaf2−/−p53−/− appeared physiologically and histologically normal at weaning, females had a statistically significant decrease in survival compared with Eaf2−/−p53−/− males (Supplemental Fig. 1D (931.7KB, TIF) ). Necropsies of female Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice revealed thymic lymphoma in four of five animals, lymphoma in multiple organs including the ovaries, as well as the development of ovarian cysts (data not shown). The absence of Eaf2 is not associated with impaired recovery of females (19), and Eaf2-deficient females are fertile and have a normal lifespan (unpublished data). In addition to decreased recovery of females, loss of p53 has been reported to significantly reduce fertility rates (35). Of the Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice generated, 24 were males and 5 were females. None of these five female Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice was successfully mated, whereas several of the male Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice sired litters. Eaf2−/−p53+/− females were successfully mated, and their survival was not significantly altered compared with Eaf2−/−p53+/− mice up to 8 months of age. Eaf2−/−p53+/− females were not followed for survival, nor were they examined for histological defects.

A total of 149 mice with eight different genotypes were studied for up to 540 days with respect to survival and prostatic defects (Table 2). Because mice on a p53−/− background had median survival ranging between 132 days for Eaf2+/−p53−/− and 175 days for Eaf2−/−p53−/−, an additional 9 wild-type and 11 Eaf2−/−p53+/+ mice were euthanized at 130 to 180 days as age-matched controls for determining the effects of Eaf2 deficiency on p53−/− mice. As expected, loss of Eaf2 alone induced mPIN lesions at advanced age (∼540 days, 10 of 15 compared with none of 11 at ∼145 days), which did not progress to adenocarcinoma. Significant prostatic defects including mPIN and adenocarcinoma were induced by combined deficiency in Eaf2 and p53. Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice had a statistically significant increase in the incidence of prostate adenocarcinoma (6 of 11) compared with Eaf2−/−p53+/+ mice (none of 11) (P = 0.0124) (Fig. 3A; Table 2). Eaf2−/− p53+/+ mice at 4 to 6 months of age did not develop mPIN lesions; however, Eaf2+/−p53−/− developed mPIN (5 of 11) and one case of prostate adenocarcinoma. Homozygous loss of Eaf2 on a p53−/− background induced a statistically significant increase in Ki67-positive proliferating cells (Fig. 3B and 3C), but it had no effect on proliferation on a p53+/− background at age 4 to 6 months (data not shown). Eaf2+/−p53−/− displayed a significant increase in Ki-67–positive cells, in agreement with the increased incidence in mPIN lesions. Compared with wild-type controls as well as age-matched Eaf2−/− mice, Eaf2+/−p53−/− and Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice had a statistically significant increase in the number of Ki-67–positive cells (Fig. 3C). All prostate tumors in Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice were confined to the prostate. As in previous reports, conventional deletion of p53 did not induce mPIN lesions (none of six in Eaf2+/+p53−/− mice, none of four in Eaf2+/+p53+/− mice) or induce increased proliferation. Immunostaining of p53 was not altered in Eaf2−/−p53+/+ prostate compared with wild-type controls (Supplemental Fig. 5 (2.1MB, TIF) ), in agreement with the lack of alteration in p53 or EAF2 protein levels in C4-2 or LNCaP cells treated with sip53 or siEAF2 (see Fig. 2G and Supplemental Fig. 3E (2MB, TIF) ). No antibodies were available at the time of this study to examine the expression of EAF2 in murine tissues; however, EAF2 is not a known p53-regulated gene in the literature (36).

Table 2.

Distribution of Mice Studied for Survival and Tumor Spectrum

| Genotype | Number of Animals Followed for Survival | Median Age at Death (d) | Number of Animals Analyzed by Necropsy | Animals With Thymic Lymphoma (%) | Number of Animals Analyzed for Prostatic Defects | Animals with mPIN (%) | Fisher Exact P Valuea | Animals With Prostate Cancer (%) | Fisher Exact P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eaf2+/+, p53−/− | 21 | 141 | 21 | 19 (91) | 6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Eaf2+/−, p53−/− | 21 | 132 | 16 | 10 (63) | 11 | 5 (45) | 0.0351 | 1 (9) | 1.0000 |

| Eaf2−/−, p53−/− | 29 | 175 | 22 | 16 (73) | 11 | 7 (55) | 0.0039 | 6 (55) | 0.0124 |

| Eaf2−/−, p53+/+ | NA | 145 | 11 | 0 (0) | 11 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Eaf2+/+, p53+/− | 9 | 442 | 6 | 2 (33) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Eaf2+/−, p53+/− | 13 | 466 | 13 | 0 (0) | 12 | 7 (58) | 0.7063 | 0 (0) | |

| Eaf2−/−, p53+/− | 20 | 417 | 14 | 1 (7) | 10 | 9 (90) | 0.3449 | 1b (10) | 0.3704 |

| Eaf2−/−, p53+/+ | 17 | 540 | 17 | 0 (0) | 15 | 10 (67) | 0 (0) | ||

| Eaf2+/−, p53+/+ | 3 | 540 | 3 | 0 (0) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Eaf2+/+, p53+/+ | 19 | 540 | 19 | 0 (0) | 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Compared with incidence in age-matched Eaf2−/−p53+/+ controls.

Sarcoma.

Figure 3.

Combined loss of Eaf2 and p53 induced prostate cancer in the mouse model. (A) Histology of mouse ventral prostate from Eaf2+/+p53+/+, Eaf2+/+p53−/−, Eaf2−/−p53+/+, Eaf2+/−p53−/−, and Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice aged 4 to 6 months stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Original magnification, ×10, inset, ×40. Scale bars, 200 μm in ×10, 50 μm in ×40. (B) Ki-67 immunostaining in transverse sections of prostate dorsal lobes from indicated genotypes at 4 to 6 months of age. Original magnification, ×20. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Quantification of Ki-67+ epithelial cells in mouse prostate at 4 to 6 months of age. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean from 7 to 12 mice per group. *P < 0.05.

Eaf2−/−p53+/− mice displayed an increased incidence of mPIN lesions compared with loss of Eaf2 alone (90% vs 67%) (Fig. 4A; Table 2), although the sample size was not sufficiently large enough to detect a statistically significant difference. One Eaf2−/−p53+/− mouse displayed prostate sarcoma at 457 days of age; however, no Eaf2−/−p53+/− mice (none of 10) examined displayed prostate adenocarcinoma (Table 2). Eaf2+/−p53+/− mice also developed mPIN lesions (58%) and a significant increase in Ki-67–positive proliferating cells compared with Eaf2+/+p53+/+ or Eaf2+/+p53+/− controls (Fig. 4B and 4C). Combined homozygous loss of Eaf2 and p53 heterozygosity induced high-grade PIN lesions accompanied by increased proliferation (Fig. 4). However, the increased proliferation was not significantly increased compared with Eaf2−/−p53+/+ mice, and no Eaf2−/−p53+/− mice displayed prostate adenocarcinoma (Fig. 4), suggesting that heterozygous deletion of p53 in the absence of wild-type Eaf2 could contribute to high-grade mPIN lesions but was insufficient to induce prostate cancer. As in previous reports, Eaf2+/+p53+/− mice did not display mPIN lesions (none of six).

Figure 4.

Effect of Eaf2 loss on heterozygous p53 mice. (A) Prostates of mice on a p53+/− background developed high-grade mPIN lesions at 17 to 20 months of age. (black arrow, Eaf2+/−p53+/− inset) and increased vessels (red arrow, Eaf2+/−p53+/− inset). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of mouse ventral prostate. Original magnification, ×10, inset, ×40. Scale bars, 200 μm in ×10, 50 μm in ×40. (B) Ki-67 immunostaining in transverse sections of prostate anterior lobes from indicated genotypes at 17 to 20 months of age. Original magnification, ×20. (C) Quantification of Ki-67+ epithelial cells in prostate at 17 to 20 months of age. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean from 7 to 12 mice per group. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

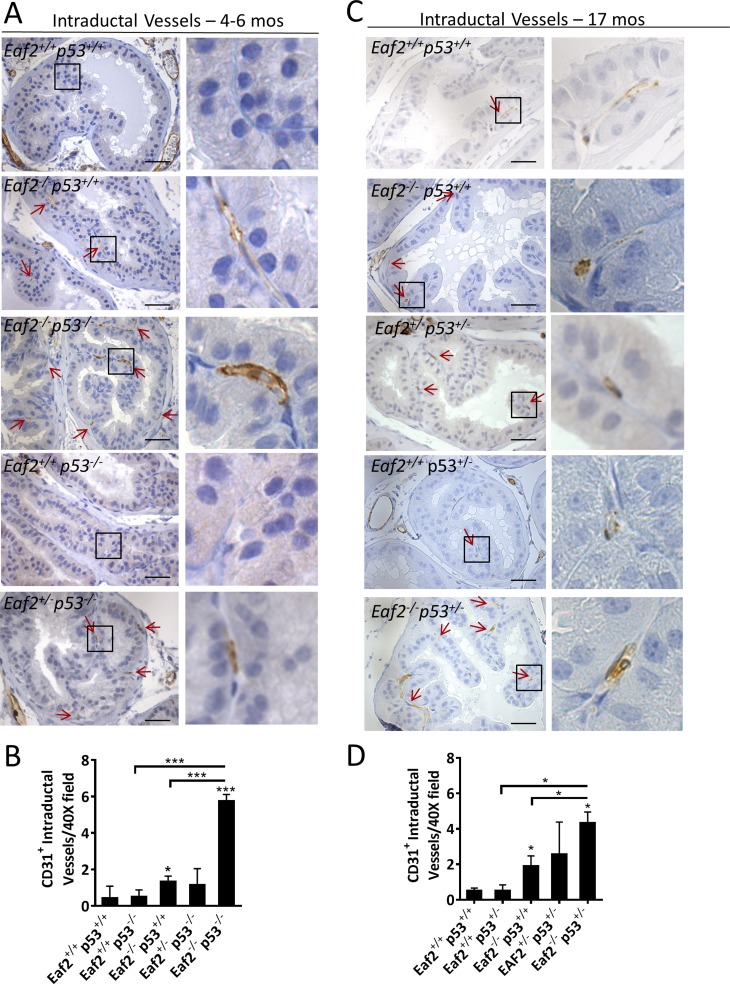

Eaf2 knockout has previously been shown to induce increased vascularity in the murine prostate, and EAF2 downregulation was correlated with increased vascularity in human prostate tumors (24). The normal prostate has prominent stromal vasculature and rarely intraductal vessels, whereas there is a noticeable migration of vessels into the prostatic duct within PIN lesions, which has been postulated as a tumor “initiation switch” (37). The intraductal microvessel density (IMVD) was determined at ×40 magnification in the dorsal prostates of Eaf2- and p53-deficient mice where the epithelial defects induced by combined loss of Eaf2 and p53 were least prominent to identify whether increased IMVD could contribute to tumor initiation. Eaf2−/−p53+/+ mice displayed a small but statistically significant increase in IMVD at 4 to 6 months of age, whereas Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice had a profound increase in intraductal vessels (Fig. 5A and 5B). Although Eaf2+/−p53−/− mice had a significant increase in proliferation at 4 to 6 months of age, IMVD was not increased. At 17 months of age, Eaf2−/−p53+/− mice also displayed a statistically significant increase in IMVD compared with Eaf2+/+p53+/+ and Eaf2−/−p53+/+ mice (Fig. 5C and 5D). Additionally, Eaf2+/−p53−/− mice also displayed an increased IMVD compared with wild-type controls. These results suggest that prostate luminal epithelial proliferation is significantly increased in mice with combined Eaf2 and p53 deficiency, and the microenvironment is highly vascularized, which may further promote increased cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis.

Figure 5.

Effect of combined loss of Eaf2 and p53 on prostate intraductal vessels. (A) CD31 immunostaining of intraductal vessels (red arrows) in transverse sections of prostate dorsal lobes from indicated genotypes at 4 to 6 months of age, and (C) at 17 months of age. (B) Quantification of CD31+ intraductal vessels in dorsal prostate at 4 to 6 months of age, and (D) at 17 months of age. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean from 7 to 12 mice per group. Original magnification, ×10, inset, ×40. Scale bars, 200 μm in ×10, 50 μm in ×40. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

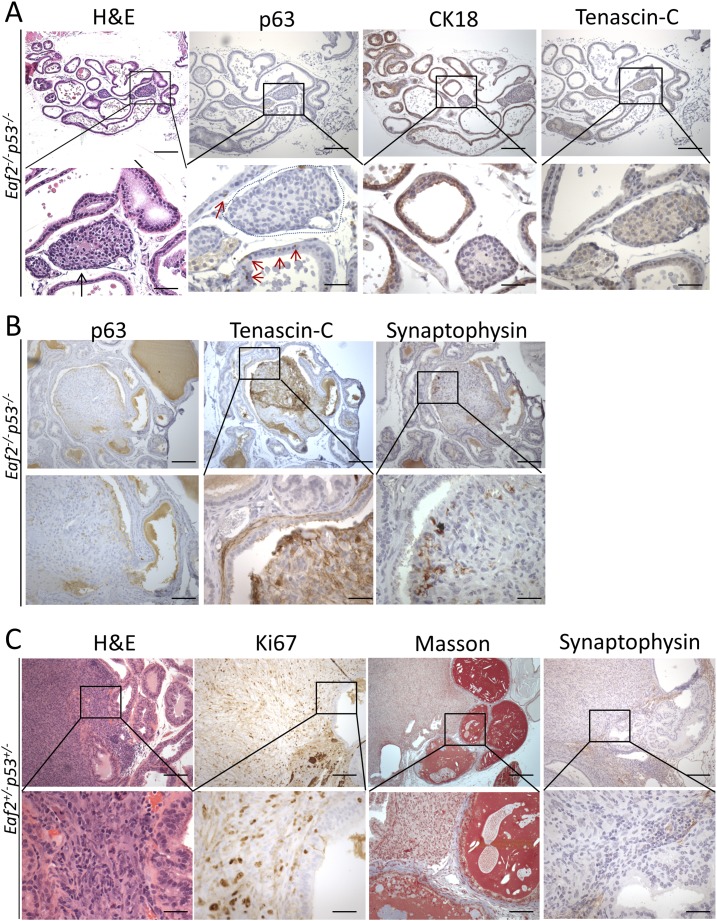

The prostate epithelial cell types are frequently identified by their expression of distinct markers. For example, luminal epithelial cells express cytokeratin 18, basal cells express p63, and neuroendocrine cells express synaptophysin (38). Prostate adenocarcinomas in the Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice were characterized by a loss of p63-positive basal cells, which is characteristic of prostate tumors (39, 40), and reduced immunostaining of cytokeratin 18 (Fig. 6A). The surrounding stroma of most tumors in Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice was not positive for reactive stromal marker tenascin-C, which has been frequently used to identify cancer-associated fibroblasts and has been associated with metastasis (41). Eaf+/+p53+/+displayed p63-positive basal cells and the absence of tenascin-C staining in the surrounding stroma (Supplemental Fig. 6 (2MB, TIF) ). One of the tumors in Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice displayed areas of positive tenascin-C immunostaining in the stroma immediately surrounding the tumor, as well as several synaptophysin-expressing neuroendocrine cells (Fig. 6B). The one prostate sarcoma identified in an Eaf2−/−p53+/− at 17 months of age was characterized by an increase in Ki-67–positive proliferating cells, as well as increased collagen surrounding the tumor and nearby glands (Fig. 6C). Neuroendocrine staining was absent in the prostate sarcoma. These results suggest that prostate tumors in the Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice had a luminal epithelial phenotype without a reactive stroma.

Figure 6.

Immunostaining analysis of prostate tumors in mice with combined deficiency in Eaf2 and p53. (A) Prostate adenocarcinomas (black arrow, H&E) identified in Eaf2−/−p53−/− mice were characterized by a loss of p63-positive basal cells (red arrow, p63, tumor outlined in blue) and a decrease in cytokeratin 18 (CK18) immunostaining of luminal epithelial cells. (B) Prostate stromal cells surrounding one adenocarcinoma in an Eaf2−/−p53−/− mouse displayed immunopositivity for reactive stroma marker tenascin-C (TNC), and a few cells in the tumor expressed neuroendocrine marker synaptophysin (see H&E in Fig. 3A). (C) The prostate sarcoma identified in one Eaf2−/−p53+/− mouse at age 17 months was characterized by an increase in Ki-67–positive cells and increased collagen in the surrounding stroma (Masson trichrome staining). No synaptophysin immunostaining was displayed. Original magnification, ×10, inset, ×40. Scale bars, 200 μm in ×10, 50 μm in ×40. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

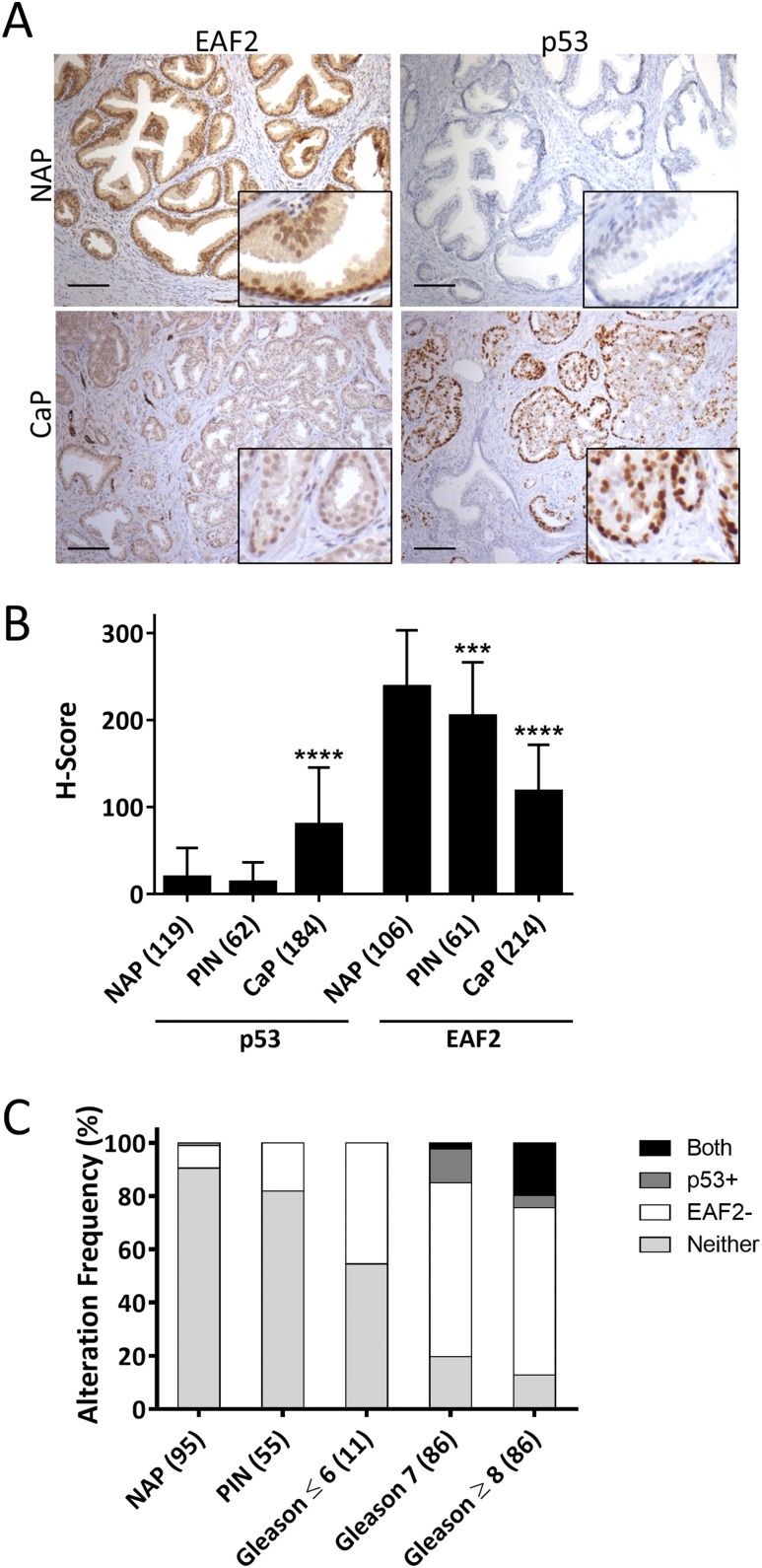

Expression of EAF2 and p53 in human prostate tissue specimens

EAF2 has previously been shown to be downregulated in advanced human prostate tumor tissue specimens (21). Most studies suggest that p53 mutation/loss is frequent in advanced stage and castration-resistant prostate cancers (3, 42). Immunohistochemical detection of p53 nuclear accumulation in tissue specimens has been highly correlated with p53 mutations in several tumor types (43, 44), including prostate cancer (42). More recently, positive p53 immunostaining was strongly associated with mutations in exons 5 to 8 of p53 (5), which are located in the domain where p53 interacts with EAF2 (see Fig. 1). The expression of p53 and EAF2 was examined in human prostate cancer tissue specimens using immunostaining of human prostate tissue specimens assembled in two TMAs as well as an additional nine patients with tumor and normal adjacent to tumor tissues (Tables 3 and 4). Tissue specimens in the TMA that did not contain prostate epithelial cells, or that were washed away during the staining process, were not scored. Compared with normal adjacent prostate (NAP) to tumor and donor prostate tissues, EAF2 expression was significantly reduced and nuclear accumulation of p53 was significantly increased in prostate cancer tissues (Fig. 7A and 7B). EAF2 expression was also significantly decreased in PIN lesions, suggesting that EAF2 downregulation might contribute to early carcinogenesis (Fig. 7B). To determine the frequency of combined alterations in p53 and EAF2 expression, aberrant expression was defined as an H score of >140 for p53 [which corresponds to strong nuclear expression in >45% of tumor cells and has been reported to correlate with p53 mutation (44)] and an H score of <150 for EAF2 (which corresponds to strong nuclear expression in <50% of tumor cells). Specimens were categorized as having p53 and EAF2 alteration (Both), p53 only (p53+), EAF2 only (EAF2−), or alteration in neither p53 nor EAF2 (Neither). Alteration in p53 staining in the absence of EAF2 downregulation was identified in one NAP specimen, but not in PIN or Gleason score of <6. p53 alteration frequency was 12.7% in Gleason score of 7 (11 of 86) and 4.7% in Gleason score of ≥8 (4 of 86). EAF2 alteration frequency in the absence of p53 alteration increased in a stepwise fashion from 8.4% in NAP (8 of 95), 18.2% in PIN (10 of 55), 45% in Gleason score of 6 (5 of 11) to ∼65% in Gleason score of 7 and Gleason score of ≥8 (56 of 86 and 54 of 86, respectively), further suggesting that EAF2 loss could contribute to the initiation and progression of prostate cancer (Table 5). The percentage of tissues with alteration in both p53 and EAF2 was significantly higher in prostate cancer specimens with Gleason score of ≥8 compared with Gleason score of 7 [19.8% (17 of 86) vs 2.32% (2 of 86), respectively, P < 0.001] (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that combined aberrant expression of EAF2 and p53 is associated with high Gleason score.

Table 3.

Demographics of Human Prostate Tissue Specimens for EAF2 and p53 Immunostaining Study

| Tissue Type | Mean Age (y) | Gleason Score | Number of Specimens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma (216 TMA, 9 slides) | 62.9 | <7 (32) | 225 |

| 7 (103) | |||

| 8 (36) | |||

| 9 (54) | |||

| High-grade PIN | 61 | 64 | |

| Normal adjacent to tumor (104 TMA, 9 slides) | 62.9 | 113 | |

| Donor | 30.9 | 16 |

Table 4.

Statistics of H Score Data for EAF2 and p53 Immunostaining Study

|

p53 |

EAF2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAP (119) | PIN (62) | CaP (184) | NAP (106) | PIN (61) | CaP (214) | |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 |

| 25% Percentile | 0 | 0 | 20 | 190 | 157.5 | 90 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 70 | 270 | 200 | 117.5 |

| 75% Percentile | 30 | 20 | 120 | 290 | 265 | 150 |

| Maximum | 190 | 105 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| Mean | 19.17 | 13.06 | 79.67 | 238 | 204.1 | 117.8 |

| SD | 33.64 | 23.34 | 65.69 | 65.22 | 62.33 | 53.92 |

| SEM | 3.084 | 2.964 | 4.843 | 6.334 | 7.981 | 3.686 |

| Lower 95% CI of mean | 13.06 | 7.138 | 70.12 | 225.5 | 188.1 | 110.5 |

| Upper 95% CI of mean | 25.28 | 18.99 | 89.23 | 250.6 | 220.1 | 125.1 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Figure 7.

(A) EAF2 and p53 immunostaining in human NAP and prostate cancer (CaP) tissue specimens. Original magnification, ×10. Scale bars, 200 μm. (B) Quantification of EAF2 staining and p53 nuclear staining intensity H score in NAP, PIN, and CaP. Data represent patients identified in Table 3 and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. TMA specimens that were washed away during the immunostaining process were not scored. C. Alteration frequency of specimens with no alteration in EAF2 or p53 expression (Neither), upregulated p53 (p53+), downregulated EAF2 (EAF2−), or concurrent upregulation of p53 and downregulation of EAF2 (Both) in NAP, PIN, and CaP with Gleason scores of <6, 7, or >8. Scoring was quantified for patients with both EAF2 and p53 immunostaining scores; specimens missing either EAF2 or p53 data due to tissue loss during the immunostaining process were not included. The numbers of patients are indicated in parentheses. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Our findings in this study demonstrate physical and functional interactions between two tumor suppressors, EAF2 and p53, in the prostate. We presented evidence for coprecipitation of endogenous p53 with EAF2, significantly increased cell proliferation and migration upon concurrent knockdown of EAF2 and p53 in C4-2 prostate cancer cell lines, and the induction of prostate carcinogenesis by concurrent knockout of Eaf2 and p53 in the mouse model. Furthermore, high Gleason score was correlated with EAF2 downregulation and p53 nuclear staining in human prostate cancer specimens. These findings suggest that simultaneous inactivation of EAF2 and p53 can drive the initiation and progression of prostate cancer.

The presence of EAF2 and p53 in the same protein complexes provides a potential mechanism for these two proteins to modulate the functions of each other. EAF2 was reported as a transcriptional elongation factor (45, 46). The transcriptional activator role of p53 is critically important for its biological effects. p53 could modulate the expression of various target genes through sequence-specific transactivation via p53-binding/responsive elements as well as sequence-independent regulation of a wide variety of genes that do not contain p53-binding/responsive elements. Pull-down and deletion mutagenesis demonstrated that the C terminus of EAF2, which contains a transactivation domain (46), interacts with the DBD of p53 in prostate cancer cells (see Fig. 1). When present in the same complex, p53 could modulate the transcription elongation activity of EAF2. Conversely, EAF2 may modulate both sequence-specific and/or sequence-independent transcriptional regulation by p53 or interfere with p53 binding to DNA. In addition to directly modulating the expression of downstream genes at transcription or transcriptional elongation, p53 and EAF2 could modulate the expression of some genes via indirect mechanisms. Analysis of the genes regulated by p53 and EAF2 will provide greater insight into the precise functional role of EAF2 interaction with p53 in prostate homeostasis.

The mechanisms by which concurrent loss of EAF2 and p53 contributes to prostate carcinogenesis are undoubtedly complex and involve multiple signaling pathways. Interestingly, note that individual deletion of either Eaf2 or p53 was insufficient to promote tumorigenesis in the murine model, whereas combined homozygous Eaf2 and p53 deletion induced prostate adenocarcinoma as early as 4 to 6 months of age. The intraductal blood vessel density is significantly higher in the prostate with loss of both Eaf2 and p53 as compared with the wild-type or the single knockout of Eaf2 or p53. This increase in blood vessels is likely to also contribute to prostate carcinogenesis (37). Murine models with conditional deletion of p53 in the prostate have also developed mPIN lesions in some models but not others, potentially due to the Cre recombinase or to genetic background. For example, PB-driven Cre induced deletion of Rb and p53 in the mouse prostate in one study induced malignant tumors coexpressing neuroendocrine and epithelial markers (16), whereas Fabpl-driven Cre recombinase induced neuroendocrine prostate tumors lacking expression of the epithelial markers keratin 17/19 in mice with combined Rb and p53 deletion in another study (18).

Recently, a p53R270H mutation model that conditionally expressed the R270H Tp53 GOF mutation in the prostate epithelium of mice was shown to develop mPIN and prostate cancer (47), suggesting that p53 gain-of-function mutations play a significantly different role in prostate carcinogenesis than that of mutations resulting in loss of p53 function. We recognize the limitation for using nuclear p53 staining as a readout for p53 abnormality in prostate cancer specimens. The nuclear staining of p53 may not differentiate inactivating from activating p53 mutants, and future studies using models such as the p53R270H mouse will be required to determine whether EAF2 downregulation also plays an important role in prostate cancers with gain-of-function p53 mutations. However, strong p53 staining was closely associated with point mutations of p53 and rapid biochemical recurrence in an analysis of a tissue microarray containing 11,152 prostate cancer samples (7). In the same study, no homozygous deletion was detected, although heterozygous p53 deletion was detected in ∼14% of the tumors. In a different study by Schlomm et al. (5), although only 38% of immunohistochemistry-positive prostate cancers were confirmed as mutated by direct sequencing of the p53 gene, p53 mutated and unmutated immunohistochemistry-positive cancers had similar poor prognosis (5). Schlomm et al. (5) suggested that p53 immunostaining positivity detected some p53 mutations that were subsequently missed by sequencing analysis because they were located in other exons or due to contamination of sample cores with nonneoplastic cells. Therefore, immunostaining of p53 provides a cost-effective approach for evaluating p53 abnormality in prostate cancer specimens.

In summary, these studies demonstrate physical and functional interactions between two important tumor suppressors, p53 and EAF2, in prostate carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marie Acquafondata, Dawn Everard, Anthony Green, Katie Leschak, Megan Lambert, Marianne Notaro, and Aiyuan Zhang for technical support.

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R0 1CA186780, P50 CA180995, R50 CA211242, and T32 DK007774 as well as by grants from the Tippins Foundation (to L.E.P.), the Mellam Family Foundation (to L.E.P. and D.W.), and the American Urological Association Foundation (to D.W.). This project used the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Animal Facility and the Tissue and Research Pathology Services and was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant P30 CA047904.

Author Contributions: Y.W. and L.E.P. conceived and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. J.A., D.W., Y.J., and M.Z. repeated cell line experiments. J.P. helped analyze animal experiments and helped write the manuscript. Q.S. and L.E.P. performed immunostaining of murine tissues. L.H.R. analyzed animal pathology. L.E.G. helped with animal experiments. J.B.N. helped design the tissue microarray, analyzed data, and helped write the manuscript. A.V.P. provided pathology assessment of human tissue specimens, supervised quantification by L.E.P., and analyzed immunostaining data. Z.W. conceived the experiments, study design, and coordination and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Correspondence and Reprint Requests: Zhou Wang, PhD, Department of Urology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, 5200 Centre Avenue, Suite G40, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15232. E-mail: wangz2@upmc.edu.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Table 5.

H Score Alteration Frequency Data for EAF2 and p53 Immunostaining Study

| Both (%) | p53+ (%) | EAF2− (%) | Neither (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAP | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (8.4) | 86 (90.5) | 95 |

| PIN | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (18.2) | 45 (81.8) | 55 |

| Gleason score of <6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 11 |

| Gleason score of 7 | 2 (2.3) | 11 (12.8) | 56 (65.1) | 17 (19.8) | 86 |

| Gleason score of ≥8 | 17 (19.8) | 4 (4.7) | 54 (62.8) | 11 (12.8) | 86 |

| Sum | 19 (5.7) | 16 (4.8) | 133 (39.9) | 165 (49.5) | 333 |

Footnotes

- BrdU

- 5-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine

- DBD

- DNA binding domain

- EAF2

- ELL-associated factor 2

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- HEK293

- human embryonic kidney 293

- IMVD

- intraductal microvessel density

- mPIN

- murine prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- NAP

- normal adjacent prostate

- NE

- nuclear extract

- PCR

- polymerase chain reaction

- PIN

- prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- SDS

- sodium dodecyl sulfate

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TMA

- tissue microarray.

References

- 1.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(1):a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science. 1994;265(5170):346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenberg HB, Sesterhenn IA, Gaddipati JP, Weghorst CM, Buzard GS, Moul JW, Srivastava S. Alteration of the tumor suppressor gene p53 in a high fraction of hormone refractory prostate cancer. J Urol. 1995;154(2 Pt 1):414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moul JW. Angiogenesis, p53, bcl-2 and Ki-67 in the progression of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 1999;35(5–6):399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlomm T, Iwers L, Kirstein P, Jessen B, Kollermann J, Minner S, Passow-Drolet A, Mirlacher M, Milde-Langosch K, Graefen M, Haese A, Steuber T, Simon R, Huland H, Sauter G, Erbersdobler A. Clinical significance of p53 alterations in surgically treated prostate cancers. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(11):1371–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ecke TH, Schlechte HH, Schiemenz K, Sachs MD, Lenk SV, Rudolph BD, Loening SA. TP53 gene mutations in prostate cancer progression. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(5):1579–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kluth M, Harasimowicz S, Burkhardt L, Grupp K, Krohn A, Prien K, Gjoni J, Hass T, Galal R, Graefen M, Haese A, Simon R, Huhne-Simon J, Koop C, Korbel J, Weischenfeld J, Huland H, Sauter G, Quaas A, Wilczak W, Tsourlakis MC, Minner S, Schlomm T. Clinical significance of different types of p53 gene alteration in surgically treated prostate cancer. Int J Cancer 2014;135(6):1369–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleihues P, Schäuble B, zur Hausen A, Estève J, Ohgaki H. Tumors associated with p53 germline mutations: a synopsis of 91 families. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(1):1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birch JM, Alston RD, McNally RJ, Evans DG, Kelsey AM, Harris M, Eden OB, Varley JM. Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in carriers of germline TP53 mutations. Oncogene. 2001;20(34):4621–4628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olivier M, Goldgar DE, Sodha N, Ohgaki H, Kleihues P, Hainaut P, Eeles RA. Li-Fraumeni and related syndromes: correlation between tumor type, family structure, and TP53 genotype. Cancer Res. 2003;63(20):6643–6650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14(19):2410–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, Weinberg RA. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey M, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA Jr, Bradley A, Donehower LA. Genetic background alters the spectrum of tumors that develop in p53-deficient mice. FASEB J. 1993;7(10):938–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA Jr, Butel JS, Bradley A. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356(6366):215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, Lin HK, Dotan ZA, Niki M, Koutcher JA, Scher HI, Ludwig T, Gerald W, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;436(7051):725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Z, Flesken-Nikitin A, Corney DC, Wang W, Goodrich DW, Roy-Burman P, Nikitin AY. Synergy of p53 and Rb deficiency in a conditional mouse model for metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(16):7889–7898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couto SS, Cao M, Duarte PC, Banach-Petrosky W, Wang S, Romanienko P, Wu H, Cardiff RD, Abate-Shen C, Cunha GR. Simultaneous haploinsufficiency of Pten and Trp53 tumor suppressor genes accelerates tumorigenesis in a mouse model of prostate cancer. Differentiation. 2009;77(1):103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parisi T, Bronson RT, Lees JA. Inactivation of the retinoblastoma gene yields a mouse model of malignant colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34(48):5890–5899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao W, Zhang Q, Habermacher G, Yang X, Zhang AY, Cai X, Hahn J, Liu J, Pins M, Doglio L, Dhir R, Gingrich J, Wang Z. U19/Eaf2 knockout causes lung adenocarcinoma, B-cell lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Oncogene. 2008;27(11):1536–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pascal LE, Vêncio RZ, Page LS, Liebeskind ES, Shadle CP, Troisch P, Marzolf B, True LD, Hood LE, Liu AY. Gene expression relationship between prostate cancer cells of Gleason 3, 4 and normal epithelial cells as revealed by cell type-specific transcriptomes. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao W, Zhang Q, Jiang F, Pins M, Kozlowski JM, Wang Z. Suppression of prostate tumor growth by U19, a novel testosterone-regulated apoptosis inducer. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4698–4704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo W, Keener AL, Jing Y, Cai L, Ai J, Zhang J, Fisher AL, Fu G, Wang Z. FOXA1 modulates EAF2 regulation of AR transcriptional activity, cell proliferation, and migration in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2015;75(9):976–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pascal LE, Ai J, Masoodi KZ, Wang Y, Wang D, Eisermann K, Rigatti LH, O’Malley KJ, Ma HM, Wang X, Dar JA, Parwani AV, Simons BW, Ittman MM, Li L, Davies BJ, Wang Z. Development of a reactive stroma associated with prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in EAF2 deficient mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascal LE, Ai J, Rigatti LH, Lipton AK, Xiao W, Gnarra JR, Wang Z. EAF2 loss enhances angiogenic effects of Von Hippel-Lindau heterozygosity on the murine liver and prostate. Angiogenesis. 2011;14(3):331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ai J, Pascal LE, O’Malley KJ, Dar JA, Isharwal S, Qiao Z, Ren B, Rigatti LH, Dhir R, Xiao W, Nelson JB, Wang Z. Concomitant loss of EAF2/U19 and Pten synergistically promotes prostate carcinogenesis in the mouse model. Oncogene. 2014;33(18):2286–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su F, Pascal LE, Xiao W, Wang Z. Tumor suppressor U19/EAF2 regulates thrombospondin-1 expression via p53. Oncogene. 2010;29(3):421–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao W, Jiang F, Wang Z. ELL binding regulates U19/Eaf2 intracellular localization, stability, and transactivation. Prostate. 2006;66(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strasser A, Harris AW, Jacks T, Cory S. DNA damage can induce apoptosis in proliferating lymphoid cells via p53-independent mechanisms inhibitable by Bcl-2. Cell. 1994;79(2):329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shappell SB, Thomas GV, Roberts RL, Herbert R, Ittmann MM, Rubin MA, Humphrey PA, Sundberg JP, Rozengurt N, Barrios R, Ward JM, Cardiff RD. Prostate pathology of genetically engineered mice: definitions and classification. The consensus report from the Bar Harbor meeting of the Mouse Models of Human Cancer Consortium Prostate Pathology Committee. Cancer Res. 2004;64(6):2270–2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brawer MK, Peehl DM, Stamey TA, Bostwick DG. Keratin immunoreactivity in the benign and neoplastic human prostate. Cancer Res. 1985;45(8):3663–3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owczarzy R, Tataurov AV, Wu Y, Manthey JA, McQuisten KA, Almabrazi HG, Pedersen KF, Lin Y, Garretson J, McEntaggart NO, Sailor CA, Dawson RB, Peek AS. IDT SciTools: a suite for analysis and design of nucleic acid oligomers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W163–W169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takayama K, Horie-Inoue K, Katayama S, Suzuki T, Tsutsumi S, Ikeda K, Urano T, Fujimura T, Takagi K, Takahashi S, Homma Y, Ouchi Y, Aburatani H, Hayashizaki Y, Inoue S. Androgen-responsive long noncoding RNA CTBP1-AS promotes prostate cancer. EMBO J. 2013;32(12):1665–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstrong JF, Kaufman MH, Harrison DJ, Clarke AR. High-frequency developmental abnormalities in p53-deficient mice. Curr Biol. 1995;5(8):931–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sah VP, Attardi LD, Mulligan GJ, Williams BO, Bronson RT, Jacks T. A subset of p53-deficient embryos exhibit exencephaly. Nat Genet. 1995;10(2):175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Embree-Ku M, Boekelheide K. Absence of p53 and FasL has sexually dimorphic effects on both development and reproduction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2002;227(7):545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P, Levine A. Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(5):402–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huss WJ, Hanrahan CF, Barrios RJ, Simons JW, Greenberg NM. Angiogenesis and prostate cancer: identification of a molecular progression switch. Cancer Res. 2001;61(6):2736–2743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: new prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010;24(18):1967–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bostwick DG, Brawer MK. Prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia and early invasion in prostate cancer. Cancer. 1987;59(4):788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bostwick DG. Prospective origins of prostate carcinoma. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia. Cancer. 1996;78(2):330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ni WD, Yang ZT, Cui CA, Cui Y, Fang LY, Xuan YH. Tenascin-C is a potential cancer-associated fibroblasts marker and predicts poor prognosis in prostate cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486(3):607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bookstein R, MacGrogan D, Hilsenbeck SG, Sharkey F, Allred DC. p53 is mutated in a subset of advanced-stage prostate cancers. Cancer Res. 1993;53(14):3369–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esrig D, Spruck CH III, Nichols PW, Chaiwun B, Steven K, Groshen S, Chen SC, Skinner DG, Jones PA, Cote RJ. p53 nuclear protein accumulation correlates with mutations in the p53 gene, tumor grade, and stage in bladder cancer. Am J Pathol. 1993;143(5):1389–1397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baas IO, Mulder JW, Offerhaus GJ, Vogelstein B, Hamilton SR. An evaluation of six antibodies for immunohistochemistry of mutant p53 gene product in archival colorectal neoplasms. J Pathol. 1994;172(1):5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kong SE, Banks CA, Shilatifard A, Conaway JW, Conaway RC. ELL-associated factors 1 and 2 are positive regulators of RNA polymerase II elongation factor ELL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(29):10094–10098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simone F, Luo RT, Polak PE, Kaberlein JJ, Thirman MJ. ELL-associated factor 2 (EAF2), a functional homolog of EAF1 with alternative ELL binding properties. Blood. 2003;101(6):2355–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vinall RL, Chen JQ, Hubbard NE, Sulaimon SS, Shen MM, Devere White RW, Borowsky AD. Initiation of prostate cancer in mice by Tp53R270H: evidence for an alternative molecular progression. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5(6):914–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]