ABSTRACT

Post-translational prenylation mechanisms, including farnesylation and geranylgeranylation, mediate both subcellular localization and protein-protein interaction in eukaryotes. The prenyltransferase complex is an αβ heterodimer in which the essential α-subunit is common to both the farnesyltransferase and the geranylgeranyltransferase type-I enzymes. The β-subunit is unique to each enzyme. Farnesyltransferase activity is an important mediator of protein localization and subsequent signaling for multiple proteins, including Ras GTPases. Here, we examined the importance of protein farnesylation in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus through generation of a mutant lacking the farnesyltransferase β-subunit, ramA. Although farnesyltransferase activity was found to be non-essential in A. fumigatus, diminished hyphal outgrowth, delayed polarization kinetics, decreased conidial viability, and irregular distribution of nuclei during polarized growth were noted upon ramA deletion (ΔramA). Although predicted to be a target of the farnesyltransferase enzyme complex, we found that localization of the major A. fumigatus Ras GTPase protein, RasA, was only partially regulated by farnesyltransferase activity. Furthermore, the farnesyltransferase-deficient mutant exhibited attenuated virulence in a murine model of invasive aspergillosis, characterized by decreased tissue invasion and development of large, swollen hyphae in vivo. However, loss of ramA also led to a Cyp51A/B-independent increase in resistance to triazole antifungal drugs. Our findings indicate that protein farnesylation underpins multiple cellular processes in A. fumigatus, likely due to the large body of proteins affected by ramA deletion.

KEYWORDS: antifungal resistance, Aspergillus, farnesylation, farnesyltransferase, filamentous fungus, prenylation, Ras

Introduction

Protein farnesylation, one of 2 types of post-translational prenylation modification, plays an important role in the spatiotemporal regulation of many proteins. Farnesylation promotes membrane association of proteins by catalyzing the thioether linkage of a 15-carbon isoprenoid farnesyl moiety from farnesyl pyrophosphate to the CAAX-motif cysteine residue on the target protein. The C-terminal tetrapeptide “CAAX” motif (where C = cysteine, A = any aliphatic amino acid, and X = a variable amino acid) is the prenylation recognition sequence on target proteins. Farnesylation of CAAX motifs is an irreversible reaction and is catalyzed by the farnesyltransferase enzyme complex. The farnesyltransferase enzyme is a heterodimer composed of an α-subunit, shared with the structurally similar geranylgernayltransferase type-I complex, and a unique β-subunit.1,2 The identity of the “X” residue loosely determines prenyltransferase substrate specificity; X = methionine, serine, glutamine, cysteine, and alanine are classically associated with farnesylation, and X = leucine with geranylgeranylation.1,3-6

Deletion of either farnesyltransferase subunit severely affects fungal growth in yeast-like fungi and, when examined in the human pathogenic yeast species, causes significant reductions in virulence. For example, deletion of the common prenyltransferase α-subunit is lethal in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans, likely due to the resulting complete lack of protein prenylation in these mutants.7,8 Additionally, deletion of the farnesyltransferase β-subunit has been reported in S. cerevisiae (RAM1), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (cpp1+), and recently Cryptococcus neoformans (RAM1). Although not lethal in these yeast organisms, β-subunit deletion results in poor or no growth at lower temperatures (25–30°C) and a complete inability to support growth at 37°C, a factor critical to virulence.8-10 In contrast to the yeast-like fungi, the importance of farnesyltransferase activity has not been explored in filamentous fungi.

Aspergillus fumigatus is a ubiquitous filamentous fungal pathogen responsible for causing invasive aspergillosis (IA), a disease associated with a 40–90% mortality rate in the immunocompromised population.11 The extraordinary ability of A. fumigatus to produce invasive disease derives in part from its proficiency in maintaining proper hyphal morphogenesis under host-induced environmental stress. In this study, we sought to determine the contribution of protein farnesylation to hyphal development and virulence of this important human pathogen. We report the first successful deletion of a farnesyltransferase β-subunit, named RamA here, in a mold fungus. Although loss of farnesyltransferase activity was not lethal in A. fumigatus, ramA deletion resulted in growth abnormalities including impaired hyphal branching, delayed conidial germination, reduced conidial viability, and aberrant distribution of nuclei in growing hyphae. As a marker for loss of farnesyltransferase activity, we show that ramA deletion displaces the predicted farnesylation target RasA from the plasma membrane. Additionally, loss of ramA was associated with attenuated virulence in a neutropenic murine model of invasive aspergillosis, yet reduced susceptibility to the antifungal drug voriconazole.

Results

Loss of protein farnesylation impairs A. fumigatus hyphal growth

We previously identified the gene encoding the A. fumigatus farnesyltransferase β-subunit via BLAST analysis of the Aspergillus genome database (aspergillusgenome.org) using the S. cerevisiae RAM1 sequence as a query.12 The A. fumigatus genome contains a single RAM1-homologous gene (Afu4g10330) that comprises 7 exons and encodes a predicted protein product of 519 amino acids with a molecular weight of 56.6 kDa. BLASTP alignment of predicted Ram1-homolog proteins revealed sequence identities of 38% and 69% between the A. fumigatus sequence and the S. cerevisiae and A. nidulans sequences, respectively. Because it represents the sole RAM1 homolog in A. fumigatus, we have named this gene ramA.

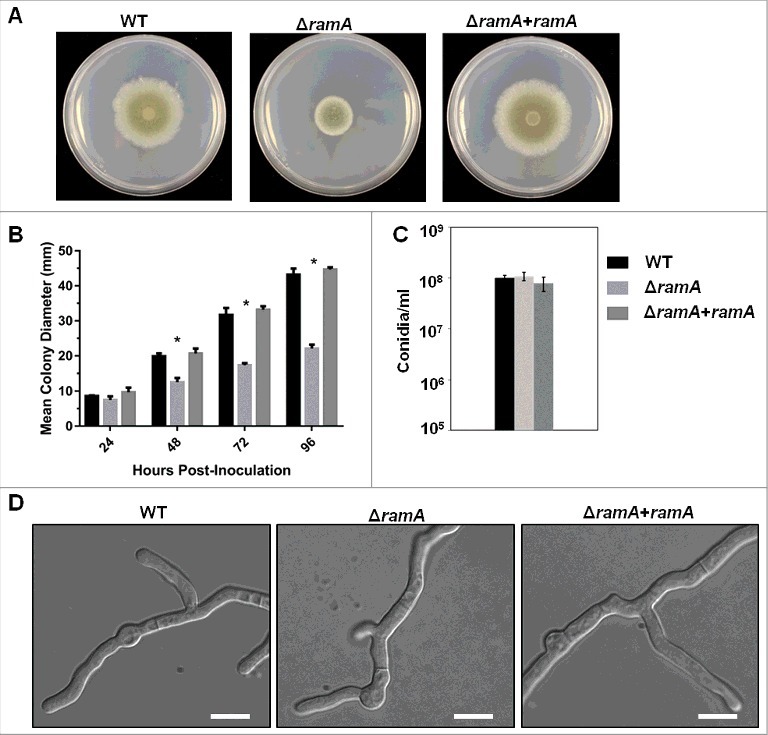

To explore roles for farnesyltransferase activity in A. fumigatus growth and virulence, a ramA deletion strain was generated. The entire ramA coding region was replaced with a deletion cassette containing the hygromycin resistance marker, using established Aspergillus transformation protocols. To confirm that all observed phenotypes in the ramA deletion strain (ΔramA) were solely a result of ramA targeting, a complemented strain was generated by ectopic re-integration of the ramA coding region. Initial examination revealed that the ΔramA mutant exhibited a deficiency in radial growth rate on GMM agar (Fig. 1A). Significant differences in colony diameter were observed after 48, 72 and 96 hours of growth at 37°C, with the ΔramA mutant colony reaching only 51.2% of the diameter of the wild type (WT) strain at 96 hours (Fig. 1B). Reduced growth of the ΔramA strain was independent of media composition (Fig. S1A). However, growth reduction caused by loss of ramA was not associated with aberrancies in conidial development. No significant differences were noted in the total number of conidia produced for each strain, regardless of media composition (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1B). Additionally, despite the reduced radial outgrowth, the ΔramA mutant displayed largely normal hyphal morphogenesis (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

A. fumigatus RamA regulates hyphal growth. (A) Colony morphology of the ramA isogenic set. GMM agar plates were inoculated with a 10 µl drop containing 1 × 104 conidia and incubated at 37°C for 96 hours. (B) Colony diameters of the ramA isogenic set measured at 24-hour intervals over the 96-hour incubation period. Measurements and error bars represent the mean and standard deviation (SD) of 3 independent experiments. Colony diameters between strains at each 24-hour interval were compared using 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism v7). Asterisks above the ΔramA strain measurement bars indicate a statistically significant difference (adjusted p value < 0.001) between the ΔramA strain and both the WT and reconstituted strains at the indicated time point. (C) Comparison of conidia generated by the isogenic set during culture on GMM. A 1 ml suspension of freshly harvested conidia at a concentration of 1 × 106 conidia/ml was spread evenly onto GMM agar and cultured for 3 d at 37°C. Conidia were harvested and enumerated on a hemocytometer. Experiments were performed in triplicate. No significant differences between strains were noted (p value > 0.05). (D) Hyphal morphology of the ramA isogenic set. Two thousand conidia from each strain were inoculated into GMM broth and incubated over sterile coverslips for 16 hours at 37°C. Scale bars represent 10 µm.

RamA controls the timing of polarity establishment and nuclear population of conidia

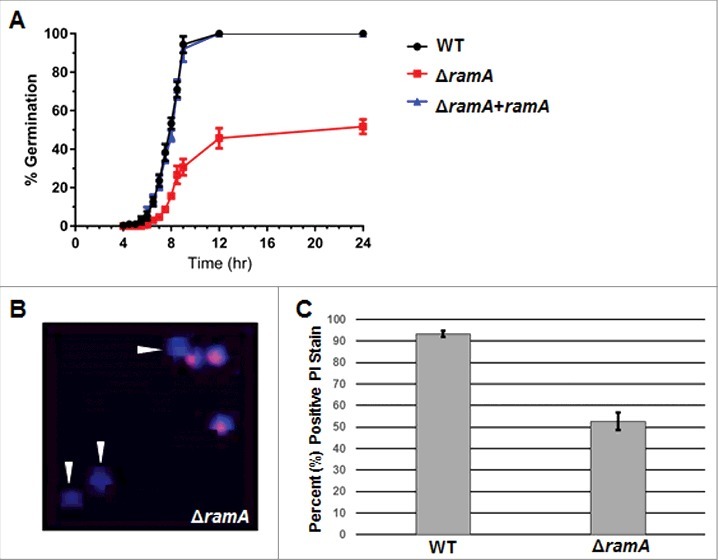

Polarity establishment, defined at the earliest time points by anisotropic conidial morphology, was delayed by approximately 2 hours in the ΔramA mutant (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the rate of polarity establishment was slowed in the ΔramA mutant when compared with the WT. Only 45.6% (±9.1%) of ΔramA conidia had formed germ tubes at 12 hours post-inoculation, by which time 100% of the conidia from the WT and complemented strains had an established polarized growth axis. At 24 hours post-inoculation, only 51.7% ( ±6.5%) of the ΔramA conidia had formed a germ tube (Fig. 2A). The conidia remaining in the ΔramA culture after 24 hours appeared dormant, with no swelling evident, indicating decreased conidial viability (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Deletion of ramA delays polarity establishment and viability. (A) Polarity establishment rates of the ramA isogenic set. Conidia (1 × 106) of each strain were inoculated on sterile coverslips submerged in GMM broth and incubated at 37°C. At the designated time points, coverslips were mounted for bright field microscopy, and one hundred conidia were examined. The percent of polarized germlings was scored as the number of conidia which had produced a visible germ tube at that time point. Measurements and error bars represent the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) of 3 independent experiments. (B) Conidia of the ΔramA strain were stained with propidium iodide (PI, red) to detect nuclear material and with calcofluor white (CFW, blue) to detect chitin in cell walls. Arrowheads denote CFW-stained conidia in which no nuclear material is detected. (C) One hundred PI-stained conidia of the wild type (WT) and ΔramA strains were examined by fluorescence microscopy, and percent positive PI staining was scored. Results are the average of 3 independent experiments ( ± SD).

To test whether the observed conidial viability deficit in the ΔramA mutant arose from a priori anucleate conidia, we first generated conidiophores on GMM agar using a slide culture technique.13 The cell wall and nuclear DNA in newly-formed conidia from conidiophores generated by this technique were visualized with calcofluor white (CFW) and propidium iodide (PI) staining, respectively. Examination of the stained conidia from each strain revealed that only 57% ( ±4.0%) of ΔramA conidia were positive for PI staining (Fig. 2B–C). This measurement corresponded to the 51.7% ( ±6.5%) of ΔramA conidia that were capable of germination (Fig. 2A). In contrast, 92% ( ±1.5%) of WT conidia were PI positive (Fig. 2C). These results are in line with the hypothesis that ramA deletion leads to increased generation of anucleate conidia and thus a conidial viability deficit. Additionally, the significant delay in the initiation of polarity noted among viable ΔramA conidia suggests that protein farnesylation is required for timely polarity establishment in A. fumigatus.

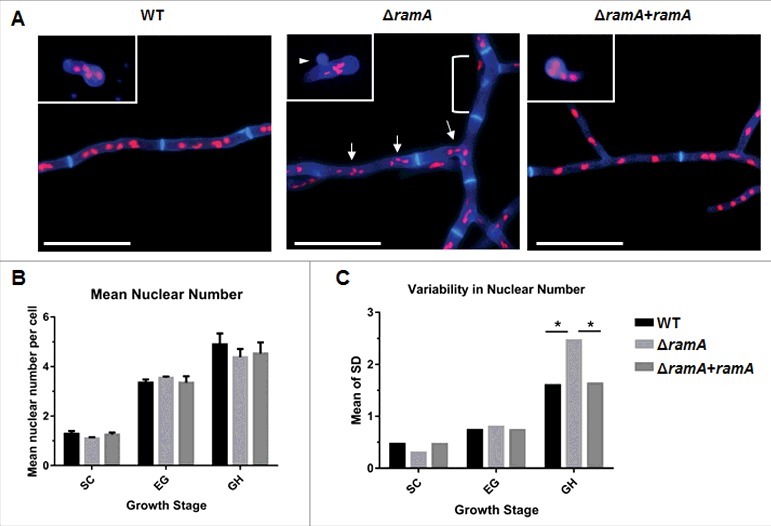

Deletion of ramA results in increased variability of nuclear number in hyphal compartments

The results presented above suggested that ramA deletion results in irregular segregation of nuclei into nascent conidia. To test whether the ΔramA mutant exhibited additional aberrancies in nuclear distribution at other developmental stages, we next examined portioning of nuclei in growing hyphae. Conidia of the ramA isogenic set were incubated to enrich for 3 distinct developmental stages,14 and cell walls and nuclear DNA visualized by CFW/PI staining. The 3 developmental stages included the following: 1) swollen conidia (SC), representing the initial break from dormancy; 2) early germlings (EG), representing unicellular germinated conidia with short germ tubes which have undergone mitosis but not yet undergone septation; and 3) growing hyphae (GH), representing a later stage of hyphal elongation after septal formation and multiple mitotic divisions.

SC and EG exhibited no significant difference in the number of nuclei per cell between strains of the isogenic set. The SC of each strain contained one to 2 nuclei each, whereas EGs of each strain contained an average of 2 to 4 nuclei (Fig. 3B). However, the positioning of nuclei within ΔramA EGs differed from the WT and complement strain. Nuclei in the ΔramA EGs were clustered near the site of the emerging germ tube, in contrast to the WT and complement strains which exhibited uniformly distributed nuclei (Fig. 3A, top). Significant aberrancies in both measures of nuclear distribution were especially apparent in the later stages of GH of ΔramA. Although the mean nuclear number of interseptal compartments was not significantly different between the strains, nuclei appeared irregularly spaced within the GH of the ΔramA mutant (Fig. 3A–B). Based on these observations, we performed a quantitative analysis to measure ΔramA deviation from WT in terms of variability of nuclear number. Quantitative comparison of the mean standard deviations produced by enumerating nuclei within interseptal compartments of GH for each strain confirmed that variability between strains was significantly different at this stage, with ΔramA displaying increased variability (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that nuclear positioning in GH is impacted by protein farnesylation.

Figure 3.

RamA is required for normal nuclear distribution in growing hyphae. (A) Nuclear positioning within germlings and hyphal compartments of the ramA isogenic set. 1 × 105 conidia of each strain were inoculated onto sterile coverslips submerged in GMM broth and incubated at 37°C for various time points to enrich for selected growth stages. Incubation times were based on the germination assay results in Fig. 2 [Swollen conidia (SC): WT, ΔramA+ramA = 5.5 hours; ΔramA = 6 hours. Early germling (EG): WT, ΔramA+ramA = 6.5 hours; ΔramA = 7.5 hours. Growing hyphae (GH): all strains = 16 hours.]. Coverslips were fixed and stained with CFW to visualize the cell wall and PI to visualize nuclei. Representative micrographs of each strain are shown. Inset images are from the EG stage, whereas the main panel displays GH stage for each strain. Note the anuclear conidium, denoted by the white arrowhead, in the ΔramA EG inset micrograph. Scale bars represent 20 µm. (B) Mean nuclear number per cell of the ramA isogenic set. The number of nuclei within 20 conidia, germlings, or subapical interseptal compartments was enumerated. Nuclei were identified as discrete spots of PI staining within the cell boundaries outlined with CFW. Measurements represent the mean of 3 independent experiments ( ± SD). The mean nuclear number was not statistically different between any strains at any tested growth stage. (C) Variability of nuclear number in cells of the ramA isogenic set. The SD was calculated for each combination of strain and growth stage for each of the 3 experimental replicates in (B). Variability was defined as the overall mean of the SDs of the 3 experimental replicates for each combination of strain and growth stage. Statistics were computed by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons (*, p < 0.05).

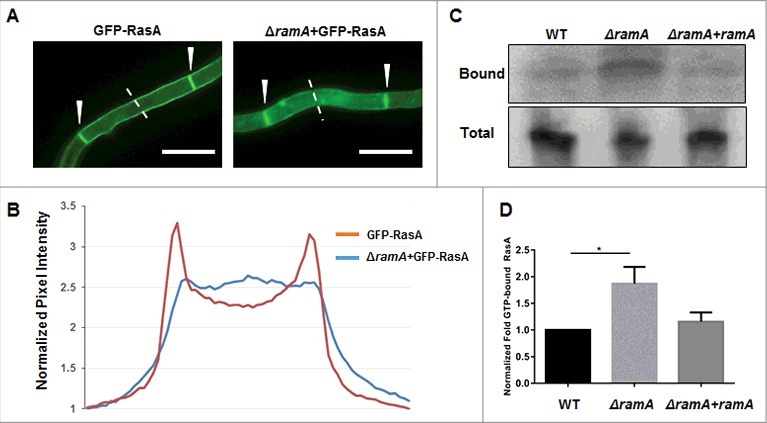

Farnesylation mediates RasA localization and activation

Complete abrogation of RasA prenylation by mutating the CAAX-motif cysteine to a serine mislocalizes RasA to the cytoplasm.15 These earlier results indicated that either post-translational farnesylation or geranylgeranylation is required for RasA association with cellular membranes. Therefore, we assessed the effect of farnesyltransferase deletion on RasA localization by expressing a GFP-RasA fusion protein in the ΔramA mutant. GFP fluorescence in the ΔramA+GFP-RasA strain was spread diffusely throughout the cytosol (Fig. 4A), with significant membrane-localized GFP signal retained only at septal membranes. This distribution was in stark contrast to the defined GFP signal along the plasma membrane seen in a strain with intact farnesylation activity (Fig. 4A). Quantitative analysis of localization confirmed a weak retention of RasA at the plasma membrane and clear accumulation at the septa in the absence of farnesyltransferase activity (Fig. 4B). To inspect the effect of loss of RasA farnesylation on its activation, we performed a Ras activation assay on the ramA isogenic set, isolating GTP-bound RasA with a Ras binding domain (RBD) polypeptide that binds RasA in a GTP-dependent manner. Immunoblotting revealed that although total RasA was decreased in the ΔramA mutant as compared with the WT and reconstituted strains, the levels of GTP-bound RasA were increased (Fig. 4C). Densitometric analysis indicated that normalized levels of GTP-bound RasA in the ΔramA mutant were almost double those of the wild type (Fig. 4D). These results demonstrate that lack of farnesylation does not negatively impact RasA activation in A. fumigatus.

Figure 4.

Loss of farnesyltransferase activity affects RasA localization to the plasma membrane. (A) Localization of RasA in the presence and absence of RamA-mediated farnesylation. A GFP-RasA fusion protein is localized to the plasma membrane and septa in the presence of RamA (GFP-RasA). RasA is partially mislocalized to the cytosol in the absence of farnesylation (ΔramA+GFP-RasA). Note the strong presence of GFP signal at the septa in both the GFP-RasA and ΔramA+GFP-RasA strains, indicated by white arrowheads. Scale bar represents 10 µm. (B) Quantitation of pixel intensity as representative quantitation of GFP-RasA localization. Pixel intensity was quantitated spanning hyphal cross-sections using the Nikon Advanced Research software package. Six independent measurements of background fluorescence in a single field (areas with no hyphal growth) were averaged for each strain and used to normalize the pixel intensity values. The graph is a representative quantitation of a single field and depicts the normalized intensities across the 8 µm dotted line pictured in panel (A). (C) Representative immunoblot of GTP-associated (i.e., activated) RasA (Bound) and total RasA (Total) in strains of the ramA isogenic set. (D) Densitometric analysis of immunoblots indicates that RasA activation is increased almost twofold in the ΔramA mutant with respect to the wild type (WT) and complement (ΔramA+ramA) strains. Measurements and error bars represent the mean of 3 independent experiments ( ± SD). Statistics were computed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons (*, p < 0.05).

A. fumigatus ΔramA exhibits attenuated virulence

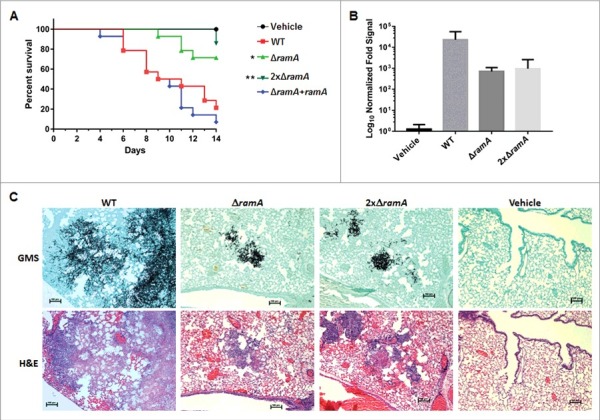

To test the importance of farnesyltransferase activity to virulence in A. fumigatus, we used a murine model of invasive aspergillosis, as described previously.16 Mice were immunosuppressed with a regimen including cyclophosphamide and triamcinolone acetonide (Fig. 5A). Mice (n = 14 per treatment group) were inoculated with freshly harvested conidia of the ramA isogenic set, as well as a double concentration of ΔramA conidia (2xΔramA) to account for the observed viability deficit. Mortality was monitored for 14 d post-inoculation. Mice infected with the ΔramA conidia exhibited decreased and delayed mortality compared with those infected with WT or reconstituted strains (Fig. 5A). Seventy-one percent of mice receiving ΔramA conidia and 85% of mice receiving 2xΔramA conidia survived until the termination of the study, compared with 21% percent of mice receiving WT conidia and 7% of mice receiving conidia of the reconstituted strain. The onset of death in mice inoculated with both concentrations of ΔramA conidia was likewise delayed; notably, the sole death in mice infected with 2xΔramA conidia occurred only at Day 14 post-inoculation. Thus, the ΔramA strain was significantly less virulent than the wild type.

Figure 5.

The ΔramA mutant exhibits attenuated virulence in a neutropenic murine model of invasive aspergillosis. (A) Survival curve for neutropenic invasive aspergillosis model. Statistics were computed by Kruskal-Wallis analysis with Dunn's test for multiple comparisons. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference in survival (pΔramA = 0.035; p2xΔramA = 0.003) between WT and ΔramA-related strains. (B) Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of fungal burden in murine lungs harvested on Day 3 post-inoculation. Measurements represent the overall mean fold qPCR signal (2−ΔCT) of 3 technical replicates ( ± SD) from each of 3 mice, normalized to the mean signal from 3 uninfected control (vehicle) mice. Statistics were computed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons. (C) Serial sections from murine lungs stained with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain (upper panels) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain (lower panels). Note the reduced hyphal outgrowth in GMS-stained lesions from lungs of mice inoculated with ΔramA strains. Scale bars represent 100 µm.

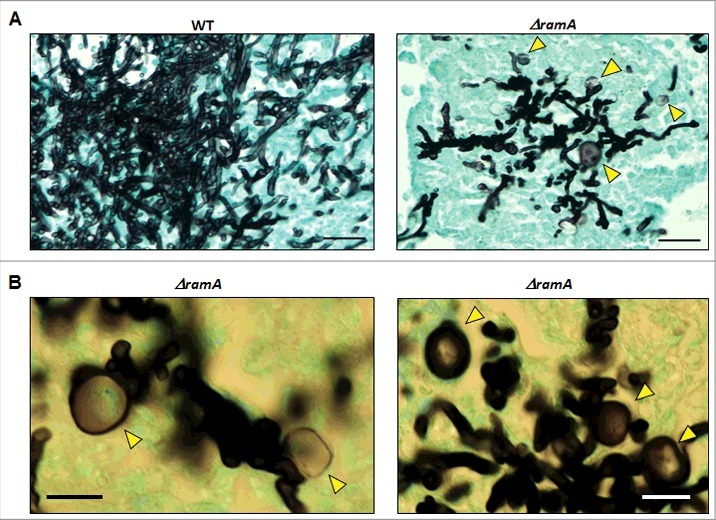

To determine relative fungal burdens in the lungs of mice infected with WT and both concentrations of ΔramA conidia versus uninfected (vehicle) control mice, we used a previously published qPCR assay.17 Comparisons did not reach statistical significance because of intra-group variability, but a trend was apparent (Fig. 5B). Fungal burden trended lower in mice infected with either concentration of ΔramA conidia than with WT conidia, correlating with reduced growth in vivo. Histopathologic examination of lung sections confirmed that hyphal growth was greatly diminished in mice inoculated with either concentration of ΔramA conidia compared with the WT (Fig. 5C, upper panels). H&E staining indicated that an inflammatory infiltrate accompanied the fungal lesions in mice infected with all strains (Fig. 5C, lower panels). Tissue from control mice contained neither lesions nor architectural changes indicating inflammation. Interestingly, lesions in mice inoculated with ΔramA conidia featured dysmorphic hyphae with swollen, blebbed structures staining positively with GMS (Fig. 6). These morphological aberrancies were not observed when the ΔramA mutant was cultured in vitro, and were also not produced by the WT strain in vivo (Fig. 6), suggesting that the lung microenvironment or other host-related factors accentuate the growth deficiencies inherent in the ΔramA mutant.

Figure 6.

The ΔramA mutant develops polarity defects in vivo. (A) Lesions formed by ΔramA exhibit dysmorphic hyphal morphology and blebbed structures (yellow arrows) in vivo, indicating a loss of hyphal polarity. Scale bars represent 25 µm. (B) Higher magnification micrographs of in vivo hyphal morphology of the ΔramA mutant. Yellow arrows denote swollen hyphal structures. Scale bars represent 12.5 µm.

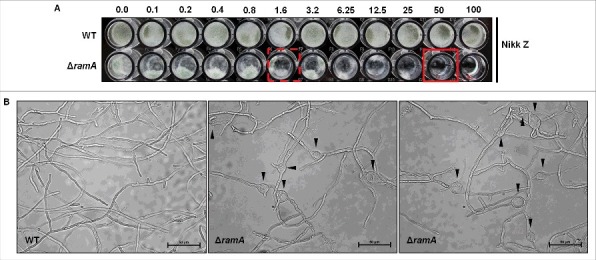

Farnesyltransferase activity is required to maintain hyphal morphology in response to nikkomycin Z

To try to recapitulate the invasive growth abnormalities of ΔramA, the isogenic set was cultured under various in vitro conditions chosen to mimic known in vivo stress. No significant differences in germination rate, growth rate, or morphology were noted in a variety of stress conditions, including dithiothreitol or brefeldin A to induce endoplasmic reticulum stress,18 iron-free media chelated with bathophenanthrolinedisulfonic acid to mimic an iron depleted environment,19 cobalt chloride to mimic a hypoxic microenvironment,20 and hydrogen peroxide to induce oxidative stress. However, when cultured with nikkomycin Z, a specific inhibitor of chitin synthase activity, growth of the ΔramA mutant was significantly inhibited by concentrations as low as 0.1 µg/ml and displayed an MIC50 of 1.6 µg/ml (Fig. 7A). Complete inhibition of growth was achieved at 50 µg/ml for the ΔramA mutant, whereas overall growth of the wild type was unimpaired (Fig. 7A). When examined microscopically, the ΔramA was found to develop swollen hyphal segments, reminiscent of the in vivo growth phenotype, at concentrations that did not affect morphology of the wild type (Fig. 7B). No changes in sensitivity to caspofungin, a specific inhibitor of glucan synthesis, were noted using similar experimental studies. These data suggeted that the cell wall defect of the ΔramA mutant was specific to chitin biosynthesis.

Figure 7.

Farnesyltransferase activity is required to support hyphal morphogenesis in response to Nikkomycin Z. (A) Broth microdilution MIC analysis of the wild type (WT) and the ΔramA mutant. Ten thousand conidia from the wild type and 20 thousand conidia from the ΔramA mutant were inoculated into GMM liquid media with ascending doses of the specific chitin synthesis inhibitor, nikkomycin Z, and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C. 50% growth inhibition (MIC50) was noted for the ΔramA mutant at 1.6 µg/ml nikkomycin Z (dashed, red square) and complete growth inhibition at 50 µg/ml (solid, red square). Nikkomycin Z MIC of the wt was not achieved (> 100 µg/ml). (B) Microscopic examination of hyphae from the wild type (wt, left panel) and the ΔramA mutant (middle and right panels) grown for 24 hrs in GMM liquid media at 37°C in the presence of 1 µg/ml nikkomycin Z. Black arrowheads denote swollen hyphal segments in the ΔramA strain.

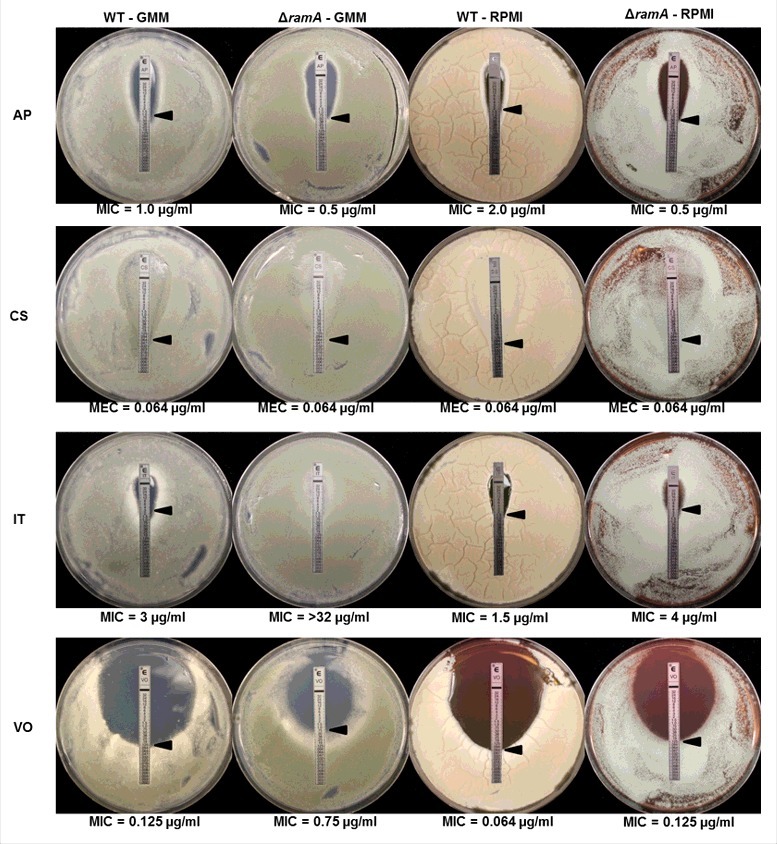

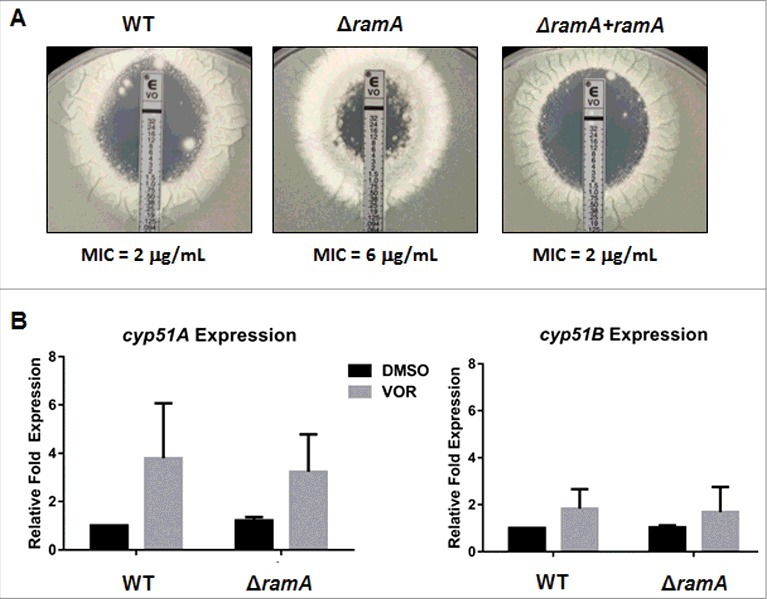

The A. fumigatus ΔramA mutant exhibits altered sensitivity to antifungals

To assess the effect of ramA deletion on the response to antifungals, we measured the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) to the ergosterol targeting compound, amphotericin B, the triazole-based ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors, voriconazole and itraconazole, and the selective inhibitor of glucan synthesis, caspofungin. MICs were determined by E-test assay on multiple media to ensure resulting phenotypes were independent of growth conditions. The MICs for voriconazole and itraconazole were consistently higher for the ΔramA mutant on all media tested, when compared with the WT strain (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9A). For Amphotericin B, the opposite trend was noted. The ΔramA mutant displayed a small but consistent decrease in Amphotericin B MIC (Fig. 8). As noted previously, no significant change in the MIC for caspofungin treatment was found by E-test assay (Fig 8). Examination of susceptibility profiles by broth microdilution, using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) methodology,21 further confirmed the resistance associated with ramA deletion (Table S2). To see if triazole resistance was specific to loss of ramA, and not associated with other slow-growth mutants, we also examined sensitivity of a rasA deletion mutant (ΔrasA) to voriconazole. Regardless of the media used, no changes in the susceptibility profile were induced by rasA deletion when analyzed by E-test or broth microdilution (Fig. S2 and Table S2). These data suggested that deletion of ramA specifically altered susceptibility to the antifungal compounds targeting ergosterol and its biosynthesis. In addition, this phenotype is not likely to be mediated via RasA signaling.

Figure 8.

The ΔramA mutant exhibits altered susceptibility profiles to antifungal drugs. The E-test method was used to delineate minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for the wild type (WT) and ramA deletion mutant (ΔramA) on GMM and RPMI agar. Antifungals tested were Amphotericin B (AP), Caspofungin (CS), Itraconazole (IT) and Voriconazole (VO). A small but consistent increase in susceptibility was noted for the ΔramA mutant in the presence of AP. In contrast, moderate and consistent increases in MIC values were noted for the ΔramA mutant in the presence of the triazoles, IT and VO. No changes in susceptibility were noted for the cell wall targeting compound, CS.

Figure 9.

The ΔramA mutant exhibits cyp51A/B-independent triazole resistance. (A) Antifungal susceptibility was performed by the E-test method, using a modified version of existing protocols. A conidial suspension of 1 × 106 conidia in 1 mL sterile water was spread on GMM+YE agar plates followed by application of E-test strips containing a voriconazole (VOR) concentration gradient of 0.002–32 µg/ml. Plates were incubated at 37°C and MIC values read at 48 h. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of cyp51A and cyp51B expression in the wild type (WT) and ΔramA strains with and without voriconazole (VOR) treatment. WT and ΔramA strains were grown in GMM+YE broth at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm for 12 hours to generate young germlings. 50% MIC VOR (as determined by E-test shown in (A)) or equal volume of DMSO (vehicle control) was added and incubation continued for an additional 6 hours. qPCR was performed on total RNA using A. fumigatus tubulin (tubA) as the endogenous standard. Each sample was analyzed in technical triplicate, and the entire assay was performed 3 times. Measurements represent the mean of 3 independent experiments ( ± SD). Statistics were computed by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey's test for multiple comparisons (*, p < 0.05).

A common mechanism for increased triazole resistance in A. fumigatus, and other pathogenic fungi, is the increased expression of the target genes required for ergosterol biosynthesis.22 We therefore sought to determine whether increased cyp51A or cyp51B expression could be correlated with the increased triazole resistance of ΔramA. To obtain sufficient hyphal mass for extraction of high-quality RNA to perform expression analyses, the WT and ΔramA strains were cultured in GMM+YE liquid media and exposed to a sub-MIC concentration of voriconazole before extraction. Voriconazole was chosen for our analyses as this is a frontline therapy for invasive aspergillosis. qRT-PCR assays were then performed to compare cyp51A and cyp51B transcript levels in the WT and ΔramA mutant, based on a previously published protocol.23 Statistical analyses revealed no significant differences in the transcript abundance of cyp51A or cyp51B in the ΔramA mutant when compared with the WT strain, regardless of the presence or absence of voriconazole (Fig. 9B). These findings suggested a non-cyp51-dependent mechanism leading to decreased triazole susceptibility when farnesyltransferase activity is lost in A. fumigatus.

Discussion

As important regulators of Ras protein localization and function, prenyltransferases have long been a focus for the development of novel anti-cancer therapeutics.24-26 Despite a conserved function among eukaryotes, recent evidence suggests that fungal farnesyltransferase enzymes could potentially serve as selective antifungal targets. Biochemical analyses have revealed key variations in the tertiary structure of the active site and product exit groove between A. fumigatus farnesyltransferase and the human homolog.27,28 These findings suggest that currently available farnesyltransferase inhibitors could be enhanced for selective toxic properties against fungal pathogens and re-purposed as antifungal agents.

Although data from the study of Cryptococcus neoformans suggest that deficiency of farnesyltransferase activity leads to reduced viability,10,29 no current reports of the importance of prenylation mechanisms in monomorphic molds exist. Our study with the A. fumigatus farnesyltransferase β-subunit, ramA, demonstrates that farnesylation influences multiple processes related to growth and development, likely through both RasA-dependent and RasA-independent mechanisms. For example, reduction of radial outgrowth and polarity establishment rates, aberrant nuclear positioning within hyphal compartments, hypersensitivity to chitin synthesis inhibition, and reduction in virulence are all phenotypes that were seen in the ΔramA mutant but are also induced by deletion or mislocalization of RasA.30,31 Therefore, RasA potentially mediates at least some aspect of these outcomes in the ΔramA mutant. However, the altered partitioning of nuclei into conidia, the loss of hyphal polarity in vivo and the increased resistance to triazoles reported here for ΔramA are not seen in rasA mutant strains30-33 (Fig. S1 and Table S2). As the protein substrates of prenylation pathways in fungi are expected to be expansive, it is assumed that these phenotypes are driven by mislocalization of additional farnesylated proteins.

The growth abnormalities reported here for the ΔramA mutant, which displays RasA protein mislocalization, did not recapitulate the previously reported severe growth and morphological defects observed in other mutants with mislocalized RasA.15,31 The ΔramA strain exhibited grossly normal hyphal morphology in vitro, a stark contrast to the stunted, hyper-branched hyphae of the RasA palmitoylation mutant (RasAC206/207S), in which all RasA palmitoylation is abrogated and RasA is mislocalized to the cytosol and endo-membranes.31 Although RasA localization was largely cytosolic upon loss of farnesyltransferase activity, a strong GFP signal was notably still present at septa, and small amounts of GFP-RasA were still visible at the plasma membrane. Together, these data suggest that the partial localization of RasA to membranes likely accounts for the lack of severe morphological defects in the ΔramA mutant. However, RasA is entirely cytosolic with no septal localization in a prenylation-deficient RasAC210S mutant,15 suggesting that the process of septal membrane targeting in the ΔramA mutant is still prenylation-dependent. This finding indicates that RasA cross-prenylation, presumably by the geranylgeranyltransferase type-1 complex, occurs when the CAAX motif cysteine is intact. Cross-prenylation of proteins by both arms of the prenyltransferase pathway has been reported in other fungi, indicating that overlap of substrate specificity is a common phenomenon for these enzymes.34,35 Regardless, the possibility exists that the differential farnesylation or geranylgeranylation of RasA may have biologic significance. Distinct lipid anchors may function to target localization of the RasA protein to different membrane compartments for specific signaling outputs. This hypothesis, and whether it holds true for other A. fumigatus proteins, is under further study. To begin to delineate the potential for cross-prenylation in A. fumigatus, we have performed in silico analyses using the Prenylation Prediction Suite (PrePS) to identify potential CAAX-motif proteins and to predict their putative prenylation status.36 Of 130 putative and verified genes encoding proteins with a carboxy-terminus that contain a cysteine at amino acid position −4 relative to the stop codon, only 28 are predicted to be prenylated CAAX-motifs (Table S3). The vast majority of these proteins are predicted to be modified by both farnesyl and geranylgeranyl moieties, suggesting promiscuous cross-prenylation for most CAAX-motif proteins in A. fumigatus (Table S3). In-depth biochemical analyses are required to assign substrate specificities for each prenyltransferase complex and to decipher whether additional CAAX motifs may serve as prenylation targets in Aspergillus.

Our virulence study is the first exploration of the importance of farnesyltransferase activity to the invasive growth of a monomorphic mold. While ramA deletion did not result in avirulence, as it does in the pathogenic yeast C. neoformans,10 virulence was attenuated, and the median onset of death was delayed. Statistical analysis of the ΔramA and 2xΔramA arms indicated no significant differences in survival between these 2 groups. These results suggest that the reduced virulence of the ΔramA mutant is not simply due to the decreased conidial viability noted in our study, nor can it be solely attributed to slow growth. Rather, it is likely that the host environment provides a further stress that negatively impacts virulence upon loss of ramA. In support of this hypothesis, the dysmorphic hyphal structures visible in lesions of the ΔramA mutant, a phenotype not observed during standard in vitro culture, indicate that host-associated factors may exacerbate the growth deficiencies related to ramA deletion. We were only able to recapitulate swollen hyphal structures in vitro by treatment with the chitin synthesis inhibitor, nikkomycin Z. The ΔramA mutant formed swollen hyphal segments at concentrations of nikkomycin Z that did not affect wild type growth. However, we noted no hypersensitivity of ΔramA to the β-glucan synthesis inhibitor, caspofungin, indicating that the ΔramA mutant is specifically defective at activating stress responses requiring regulation of chitin biosynthesis. Interestingly, our list of potentially prenylated proteins includes 2 uncharacterized homologs of a S. cerevisiae and C. albicans chitin-synthase regulator, CHS4, providing a mechanistic link to how the loss of farnesyltransferase activity may indirectly affect chitin synthase activity (Table S3). Deletion of CHS4 in S. cerevisiae causes reduced chitin deposition and altered response to cell wall active compounds.37 Therefore, it is conceivable that partial mislocalization of these putative chitin synthase regulators in A. fumigatus, via loss of prenylation, may alter the ability to activate chitin synthase enzymes in response to stress which, in turn, leads to the swollen hyphal phenotype in vivo. This interpretation implies that the lung environment is perceived as a cell wall stress by ΔramA. However, chitin synthase mutants have normal virulence levels in A. fumigatus, suggesting in vivo growth may not rely heavily on upregulation of the chitin biosynthesis machinery. Deletion of all 4 Family 2 chitin synthases in A. fumigatus leads to hyphal swelling similar to that seen with nikkomycin Z treatment and reminiscent of the in vivo growth defects of ΔramA.38 In contrast to ΔramA, this phenotype is seen in vitro without additional exogenous stress and during in vivo invasive growth, and is not associated with reduced virulence.38 Nevertheless, chitin biosynthesis in A. fumigatus is essential and requires the coordination of 8 chitin synthases that share overlapping functions. Therefore, the possibility exists that cell wall stress perceived by ΔramA during in vivo growth results in the loss-of-polarity phenotype observed in the murine model of invasive aspergillosis. The contributions of farnesylation to cell wall stress response in A. fumigatus and the extent to which this stress response supports in vivo hyphal growth are under further study.

Because farnesyl pyrophosphate is a substrate for ergosterol biosynthesis, we also hypothesized that a mutation potentially altering utilization of the cellular pool of farnesyl pyrophosphate, such as ΔramA, may affect the expression of downstream ergosterol biosynthesis genes and, therefore, sensitivity to antifungal drugs. The azole class of antifungal drugs binds and inactivates the rate-limiting enzymes in the ergosterol synthesis pathway, Cyp51A and Cyp51B,39-41 and overexpression of these target genes is a major mechanism of antifungal drug resistance.22 Although our data show that ramA deletion does alter triazole sensitivity, it does so in a manner that is not dependent on overexpression of cyp51A or cyp51B. These results suggest that farnesylation of a substrate protein may be required for its role in mediating susceptibility to inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis. Further study of RamA-mediated resistance may be of value in augmenting our understanding of mechanisms behind triazole susceptibility in A. fumigatus.

In summary, we have established that the RamA farnesyltransferase β-subunit mediates diverse biologic processes critical to growth, development, and pathogenicity in A. fumigatus. These results accentuate the value of continuing to investigate prenylation pathways as regulators of multiple developmental processes in filamentous fungi and as therapeutic targets in the treatment of invasive fungal disease.

Materials and methods

A. fumigatus strains and growth conditions

A. fumigatus strain Af293 was used as the background strain for all mutants developed in this study. The ΔrasA and GFP-RasA strains used for antifungal susceptibility and RasA localization analyses, respectively, were previously developed.30,31 All strains were maintained on glucose minimal medium (GMM), as described previously,42 and conidia used for analyses were harvested from mycelia grown on GMM for 3 d at 37°C. GMM broth was used for assays requiring growth in submerged culture. Where indicated, GMM solid agar or broth were supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (GMM+YE) to encourage robust growth. YPD (10% Yeast Extract, 20% Peptone, 20% Glucose) and RPMI-1640 (pH 7.0, buffered with MOPS) agar were also used for the examination of growth rate and conidiation. RPMI-1640 agar was used for triazole sensitivity assays by the E-test method.43

Assays to mimic in vivo stress were performed as follows. Ten thousand conidia from each strain of the ΔramA isogenic set were inoculated into 96-well plates containing GMM with serial dilutions of the following compounds: CoCl2 (0.012–1.2 mM), Brefeldin A (0.1–100 µg/ml), dithiothreitol (0.01–10 mM), H2O2 (0.01–10 mM), or nikkomycin Z (0.1–100 µg/ml). For iron limitation stress, 10 thousand conidia from each strain were cultured in iron-free GMM broth or iron-free GMM broth plus 100 uM bathophenanthrolinedisulfonic acid. All cultures were incubated at 37°C for 24 hrs. After incubation, plates were examined and images were captured on a Nikon TS100 inverted microscope equipped with a DS-FI2 digital camera.

Construction of mutant strains

For the ΔramA mutant, the entire ramA coding sequence was replaced with the hygromycin resistance cassette, as described previously.44 Oligonucleotides used for genetic manipulations are listed in Table S1. Primer pairs P1/P2 and P3/P4 were used to amplify 1.5-kb regions upstream and downstream of the predicted ramA translational start site, respectively. The PCR-amplified upstream and downstream genomic DNA fragments were subcloned into pHygR30 using NotI and XhoI/KpnI restriction sites, respectively, that were incorporated during amplification. The resulting vector was designated pΔramA-HygR. The full ramA deletion cassette was then PCR-amplified from vector pΔramA-HygR using primers P1/P4 and transformed into A. fumigatus protoplasts, using standard transformation protocols. Individual hygromycin-resistant colonies were isolated to GMM plates after 3 d of growth under hygromycin selection at 37°C. Transformants were initially screened for deletion of ramA by PCR using primers P5/P6, and then confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Complementation of ΔramA was achieved by ectopic integration of the ramA gene under the expression of the endogenous promoter. Primer pair P7/P8 was used to amplify a 3.2-kb fragment consisting of the ramA gene plus 1-kb of upstream native promoter sequence and 0.3-kb of downstream terminator sequence from the Af293 genome. The amplified fragment was subcloned as a NotI/XbaI insertion into vector pPhleoR. Vector pPhleoR was previously constructed by PCR-amplifying a phleomycin resistance cassette from vector pAN8–1 (Fungal Genetics Stock Center) using primer pair P9/P10 and sub-cloning this fragment into pBlueScript at the HindIII restriction site. The resulting transformation vector was linearized at a unique XmnI site in the backbone and transformed into ΔramA protoplasts, which were plated under phleomycin selection (125 μg/mL) and incubated at 30°C. Phleomycin-resistant colonies were isolated to GMM plates. Primer pair P2/P11 was initially used to screen for ΔramA complementation by PCR and subsequently confirmed by Southern blot analysis. Three reconstituted strains were produced, each with multiple integrations of the complementation cassette. A strain with only 2 integrations was selected as the ΔramA+ramA reconstituted strain for all subsequent experimentation. All noted phenotypes were complemented in the reconstituted strain.

For the analysis of RasA localization in the ΔramA mutant, the described previously GFP-RasA expression vector,31 which expresses GFP-tagged RasA under the RasA native promoter, was used to transform the recipient ΔramA strain. Transformants were screened for single-copy, ectopic integration and GFP fluorescence was analyzed using a Nikon NiU fluorescence microscope, equipped with a GFP filter.

Staining of the cell wall and nuclei

Existing protocols were slightly modified for nuclear and cell wall staining.14,30 Briefly, 1 × 105 conidia were incubated over sterile coverslips in GMM broth at 37°C for the indicated durations. Coverslips were washed twice for 10 min in 50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (pH 6.7) and fixed in fixative solution (8% formaldehyde in 50 mM MOPS, 25 mM EGTA [pH 7.0], 5 mM MgSO4, 5% DMSO, and 0.2% Triton-X) for 1 hr. Following fixation, coverslips were washed twice for 10 mins in MOPS buffer and incubated with 60 μg/ml RNase A (ThermoScientific) for 1 hr at 37°C. Coverslips were then washed twice for 10 mins in MOPS buffer and inverted for 5 min onto a 0.5 ml drop of staining solution containing 12.5 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) and 1 μg/ml Fluorescent Brightener 28 (Sigma). Finally, coverslips were washed twice for 10 mins in MOPS buffer and mounted for microscopy. Fluorescence microscopy was performed on a Nikon NiU microscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Qi1Mc camera using DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and mCherry filter settings. Images were captured using Nikon Elements software (v4.0).

Ras activation assay

The Ras activation assay was performed as described previously.45 Briefly, mature mycelia from the ramA isogenic set were harvested from cultures grown in GMM+YE broth at 37°C, 250 rpm, homogenized under liquid nitrogen, and resuspended in a 1:1 v/v ratio of lysis buffer containing Mg2+ and protease inhibitors (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 20 mM MgCl2, 75 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Igepal CA-630, 2% glycerol, 1:100 Pefabloc, 1:100 protein inhibitor cocktail [Sigma]). Lysates were centrifuged at 3500 rpm, 4°C, for 8 m, and supernatants were analyzed for total protein concentration via Bradford assay. GTP-bound RasA pull-down was then achieved using a Ras Activation Assay Kit (EMD Millipore #17–218), following the manufacturer protocol. For each sample, 5 mg of total protein was incubated with Raf1-RBD coated beads for 45 mins at 4°C. Beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 s, washed 3 times in 0.5 mL lysis buffer, and resuspended in 50 μL lysis buffer. Washed beads were boiled to release bound protein and immediately loaded onto a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad). Control samples, for the detection of total RasA levels, consisted of 50 μg crude lysate and were similarly boiled before SDS-PAGE separation. Membranes were probed with the anti-Ras, clone RAS10 mouse monoclonal primary antibody (1:2000 dilution, EMD Millipore) and followed by the secondary antibody, a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2a (1:2000 dilution, Abcam). Blots were imaged using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS HQ System and QuantityOne software (v4.6.5, Bio-Rad). The ratio of GTP-bound RasA to total RasA in each strain was determined by densitometric analysis using ImageJ software. The assay was performed in biologic triplicate.

Analysis of cyp51A and cyp51B expression

A modification of a previously-described protocol for voriconazole treatment was used to generate mycelia for qRT-PCR analysis.23 Briefly, 3 × 107 conidia of the wild type strain and 6 × 107 conidia of the ΔramA strain were inoculated into GMM+YE broth and incubated at 37°C. After 12 hr incubation, a concentration of voriconazole solubilized in DMSO equal to 50% of the MIC for each strain as determined by E-test assay (Af293 = 1 μg/ml; ΔramA = 3 μg/ml) was added to the treatment cultures. An equal volume of DMSO vehicle was added to control cultures of each strain. Incubation was continued at 37°C for 6 hr. Extraction of total RNA and synthesis of cDNA was performed using the Qiagen RNEasy Mini Kit and New England Biolabs ProtoScript II cDNA Synthesis Kit, respectively.

Biological triplicates of each treatment condition were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) in technical triplicate using A. fumigatus tubA (tubulin) as the endogenous standard. Target amplification primers for cyp51A (P12/ P13) and cyp51B (P14/P15) were as described previously.39 The qRT-PCR analyses were conducted on an Applied Biosystems StepOne Real-Time PCR system, and data were analyzed by relative quantitation to wild type DMSO transcription levels using the ΔΔCT method (StepOne Software, v2.2.2).

Virulence studies

All work was conducted with the formal approval of the University of South Alabama Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A neutropenic murine model of IA was used to assess the effects of ramA deletion on survival and disease pathology. Six-week-old male CF-1 mice (Charles River) were immunosuppressed according to a previously-described neutropenic model.16 In brief, immunosuppression was achieved with cyclophosphamide (150 mg/kg of body weight) injected intraperitoneally at 3 d before conidial inoculation, and 3 and 7 d post-inoculation; and triamcinolone acetonide (40 mg/kg of body weight) injected subcutaneously at 1 day before inoculation. Freshly-harvested conidia of the wild type and ΔramA strains were inoculated intranasally at a dose of 1 × 105 conidia in a 20 μl volume of sterile, pyrogen-free cell culture water (EMD Millipore) on Day 0 (n = 14 mice per strain treatment group). An additional treatment group was inoculated with a double concentration of ΔramA conidia (2 × 105 conidia) to account for the observed conidial viability deficit in the ΔramA strain. Mice were transiently anesthetized with 3.5% isoflurane before conidial inoculation. Mortality was monitored for the ensuing 14 days, and moribund mice killed by CO2 euthanasia. Survival was plotted on a Kaplan-Meier curve. Pairwise survival comparisons of all treatment groups vs. the wild type strain were performed by Kruskal-Wallis (nonparametric one-way ANOVA) analysis with Dunn's post-hoc testing (GraphPad Prism v6).

Analysis of fungal burden and histopathology

For analysis of fungal burden, fresh lung tissue of the entire right lung was processed as described previously.17 Briefly, lungs from each treatment arm were homogenized and lysed in equal volumes of lysis buffer (1 M Tris-HCl, 250 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 5 M NaCl, 10% SDS, 10 mg/ml Proteinase K) and 0.9% saline solution. Lysed lungs were incubated for 18 h at 56°C and the total genomic DNA was extracted as described previously.33 Quantitative-PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed in technical triplicate for each sample using established amplification primers P16 and P17 (Table S1) to amplify a region of the A. fumigatus 18S rRNA gene.17 Each sample reaction was performed in PrimeTime® Gene Expression Master Mix (Integrated DNA Technologies). qPCR was conducted on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR system running Bio-Rad CFX Manager software (v1.1). DNA amplification in infected samples was analyzed by normalization to mean transcription levels in uninfected control samples by the ΔCT method. Statistical analysis to compare relative signals between each strain treatment was performed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons.

For analysis of histopathology, 6-week-old male CF-1 mice (Charles River) were immunosuppressed, inoculated with conidia, and killed according to the regimen described above (n = 2 mice per strain treatment group). Thoracotomy was performed, and lungs were inflated with approximately 1 mL of a 10% buffered formalin solution (10% v/v 37% formaldehyde, 4 g/L monobasic sodium phosphate, 6.5 g/L dibasic sodium phosphate) and removed from the carcass. The superior, middle, and inferior lobes of the right lung were each sectioned transversely into 3 slices and submitted in 10% buffered formalin to the University of South Alabama Medical Center Electron Microscopy Laboratory (Mobile, AL) for paraffin embedding. Paraffin-embedded blocks were then submitted to the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Dermatopathology Laboratory (Memphis, TN) for microtome sectioning and staining. Two serial 5-μm sections were cut from the blocks; one section was stained with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain and the other with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). These stains were chosen to evaluate fungal growth and host inflammatory response in the neutropenic immunosuppression model. The presence of fungal hyphae and/or inflammatory nuclei was assessed by microscopy.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant R01AI106925 to JRF.

References

- [1].Casey PJ, Seabra MC. Protein Prenyltransferases. J Biol Chem 1996; 271:5289-92; PMID:8621375; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Seabra MC, Reiss Y, Casey PJ, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Protein farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase share a common α subunit. Cell 1991; 65:429-34; PMID:2018975; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90460-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Omer CA, Gibbs JB. Protein prenylation in eukaryotic microorganisms: genetics, biology and biochemistry. Mol Microbiol 1994; 11:219-25; PMID:8170384; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhang FL, Casey PJ. Protein Prenylation: Molecular Mechanisms and Functional Consequences. Ann Rev Biochem 1996; 65:241-69; PMID:8811180; https://doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.biochem.65.1.24110.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Scott Reid T, Terry KL, Casey PJ, Beese LS. Crystallographic Analysis of CaaX Prenyltransferases Complexed with Substrates Defines Rules of Protein Substrate Selectivity. J Mol Biol 2004; 343:417-33; PMID:15451670; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Moores SL, Schaber MD, Mosser SD, Rands E, O'Hara MB, Garsky VM, Marshall MS, Pompliano DL, Gibbs JB. Sequence dependence of protein isoprenylation. J Biol Chem 1991; 266:14603-10; PMID:1860864 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Song JL, White TC. RAM2: an essential gene in the prenylation pathway of Candida albicans. Microbiology 2003; 149:249-59; PMID:12576598; https://doi.org/ 10.1099/mic.0.25887-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].He B, Chen P, Chen S-Y, Vancura KL, Michaelis S, Powers S. RAM2, an essential gene of yeast, and RAM1 encode the two polypeptide components of the farnesyltransferase that prenylates a-factor and Ras proteins. PNAS 1991; 88:11373-7; PMID:1763050; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yang W, Urano J, Tamanoi F. Protein farnesylation is critical for maintaining normal cell morphology and canavanine resistance in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:429-38; PMID:10617635; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.275.1.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Esher SK, Ost KS, Kozubowski L, Yang D-H, Kim MS, Bahn Y-S, Alspaugh JA, Nichols CB. Relative Contributions of Prenylation and Postprenylation Processing in Cryptococcus neoformans Pathogenesis. mSphere 2016; 1(2):e00084-15; PMID:27303728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lin S-J, Schranz J, Teutsch SM. Aspergillosis Case-Fatality Rate: Systematic Review of the Literature. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:358-66; PMID:11170942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Al Abdallah Q, Fortwendel JR. Exploration of Aspergillus fumigatus Ras pathways for novel antifungal drug targets. Front Microbiol 2015; 6:128; PMID:25767465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ishi K, Maruyama JI, Juvvadi PR, Nakajima H, Kitamoto K. Visualizing Nuclear Migration during Conidiophore Development in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus oryzae: Multinucleation of Conidia Occurs through Direct Migration of Plural Nuclei from Phialides and Confers Greater Viability and Early Germination in Aspergillus oryzae. Biosci Biotech Biochem 2005; 69:747-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Momany M, Taylor I. Landmarks in the early duplication cycles of Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus nidulans: polarity, germ tube emergence and septation. Microbiology 2000; 146:3279-84; PMID:11101686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Norton TS, Fortwendel JR. Control of Ras-Mediated Signaling in Aspergillus fumigatus. Mycopathologia 2014; 178(5–6):325-30:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fortwendel JR, Zhao W, Bhabhra R, Park S, Perlin DS, Askew DS, Rhodes JC. A Fungus-Specific Ras homolog contributes to the Hyphal growth and virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell 2005; 4:1982-9; PMID:16339716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bowman JC, Abruzzo GK, Anderson JW, Flattery AM, Gill CJ, Pikounis VB, Schmatz DM, Liberator PA, Douglas CM. Quantitative PCR assay to measure Aspergillus fumigatus burden in a Murine model of Disseminated Aspergillosis: Demonstration of efficacy of Caspofungin Acetate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001; 45:3474-81; PMID:11709327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Richie DL, Hartl L, Aimanianda V, Winters MS, Fuller KK, Miley MD, White S, McCarthy JW, Latgé JP, Feldmesser M, et al.. A Role for the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) in Virulence and Antifungal Susceptibility in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog 2009; 5:e1000258; PMID:19132084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schrettl M, Beckmann N, Varga J, Heinekamp T, Jacobsen ID, Jöchl C, Moussa TA, Wang S, Gsaller F, Blatzer M, et al.. HapX-mediated adaption to iron starvation is crucial for virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLOS Pathog 2010; 6:e1001124; PMID:20941352; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lee H, Bien CM, Hughes AL, Espenshade PJ, Kwon-Chung KJ, Chang YC. Cobalt chloride, a hypoxia-mimicking agent, targets sterol synthesis in the pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol 2007; 65:1018-33; PMID:17645443; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05844.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Guinea J, Peláez T, Alcalá L, Bouza E. Correlation between the E test and the CLSI M-38 A microdilution method to determine the activity of amphotericin B, voriconazole, and itraconazole against clinical isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. Diagnost Microbiol Infect Dis 2007; 57:273-6; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gonçalves SS, Souza ACR, Chowdhary A, Meis JF, Colombo AL. Epidemiology and molecular mechanisms of antifungal resistance in Candida and Aspergillus. Mycoses 2016; 59:198-219; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/myc.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Blosser SJ, Cramer RA. SREBP-Dependent Triazole Susceptibility in Aspergillus fumigatus is mediated through Direct Transcriptional Regulation of erg11A (cyp51A). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:248-57; PMID:22006005; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/AAC.05027-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sepp-Lorenzino L, Ma Z, Rands E, Kohl NE, Gibbs JB, Oliff A, Rosen N. A Peptidomimetic inhibitor of Farnesyl: Protein transferase blocks the anchorage-dependent and -independent growth of human tumor cell lines. Can Res 1995; 55:5302-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Appels NMGM, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Development of Farnesyl Transferase Inhibitors: A Review. Oncologist 2005; 10:565-78; PMID:16177281; https://doi.org/ 10.1634/theoncologist.10-8-565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Philips MR, Cox AD. Geranylgeranyltransferase I as a target for anti-cancer drugs. J Clin Invest 2007; 117:1223-5; PMID:17476354; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI32108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hast MA, Nichols CB, Armstrong SM, Kelly SM, Hellinga HW, Alspaugh JA, Beese LS. Structures of Cryptococcus neoformans Protein Farnesyltransferase Reveal Strategies for Developing Inhibitors That Target Fungal Pathogens. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:35149-62; PMID:21816822; https://doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M111.250506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mabanglo MF, Hast MA, Lubock NB, Hellinga HW, Beese LS. Crystal structures of the fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus protein farnesyltransferase complexed with substrates and inhibitors reveal features for antifungal drug design. Prot Sci 2014; 23:289-301; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/pro.2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vallim MA, Fernandes L, Alspaugh JA. The RAM1 gene encoding a protein-farnesyltransferase {beta}-subunit homologue is essential in Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology 2004; 150:1925-35; PMID:15184578; https://doi.org/ 10.1099/mic.0.27030-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fortwendel JR, Fuller KK, Stephens TJ, Bacon WC, Askew DS, Rhodes JC. Aspergillus fumigatus RasA regulates asexual development and cell wall integrity. Eukaryot Cell 2008; 7:1530-9; PMID:18606827; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/EC.00080-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fortwendel JR, Juvvadi PR, Rogg LE, Asfaw YG, Burns KA, Randell SH, Steinbach WJ. Plasma membrane localization is required for RasA-mediated polarized morphogenesis and virulence of Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell 2012; 11:966-77; PMID:22562470; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/EC.00091-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fortwendel JR, Juvvadi PR, Rogg LE, Steinbach WJ. Regulatable Ras Activity is critical for Proper Establishment and Maintenance of Polarity in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell 2011; 10:611-5; PMID:21278230; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/EC.00315-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fortwendel JR, Panepinto JC, Seitz AE, Askew DS, Rhodes JC. Aspergillus fumigatus rasA and rasB regulate the timing and morphology of asexual development. Fung Genet Biol 2004; 41:129-39; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.fgb.2003.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Trueblood CE, Ohya Y, Rine J. Genetic evidence for in vivo cross-specificity of the CaaX-box protein prenyltransferases farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase-I in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 1993; 13:4260-75; PMID:8321228; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.13.7.4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kelly R, Card D, Register E, Mazur P, Kelly T, Tanaka K-I, Onishi J, Williamson JM, Fan H, Satoh T, et al.. Geranylgeranyltransferase I of Candida albicans: Null mutants or enzyme inhibitors produce unexpected Phenotypes. J Bacteriol 2000; 182:704-13; PMID:10633104; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/JB.182.3.704-713.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Maurer-Stroh S, Koranda M, Benetka W, Schneider G, Sirota FL, Eisenhaber F. Towards Complete Sets of Farnesylated and Geranylgeranylated Proteins. PLOS Comp Biol 2007; 3:e66; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Trilla JA, Cos T, Duran A, Roncero C. Characterization of CHS4 (CAL2), a Gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Involved in Chitin Biosynthesis and Allelic to SKT5 and CSD4. Yeast 1997; 13:795-807; PMID:9234668; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199707)13:9%3c795::AID-YEA139%3e3.3.CO;2-C10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199707)13:9%3c795::AID-YEA139%3e3.0.CO;2-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Muszkieta L, Aimanianda V, Mellado E, Gribaldo S, Alcàzar-Fuoli L, Szewczyk E, Prevost MC, Latgé JP. Deciphering the role of the chitin synthase families 1 and 2 in the in vivo and in vitro growth of Aspergillus fumigatus by multiple gene targeting deletion. Cell Microbiol 2014; 16:1784-805; PMID:24946720; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/cmi.12326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mellado E, Diaz-Guerra TM, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. Identification of two different 14-α Sterol Demethylase-Related Genes (cyp51A and cyp51B) in Aspergillus fumigatus and Other Aspergillus species. J Clin Microbiol 2001; 39:2431-8; PMID:11427550; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2431-2438.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Alcazar-Fuoli L, Mellado E, Garcia-Effron G, Lopez JF, Grimalt JO, Cuenca-Estrella JM, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. Ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus. Steroids 2008; 73:339-47; PMID:18191972; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bossche HV, Koymans L, Moereels H. P450 inhibitors of use in medical treatment: Focus on mechanisms of action. Pharmacol Therapeut 1995; 67:79-100; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fortwendel JR, Juvvadi PR, Pinchai N, Perfect BZ, Alspaugh JA, Perfect JR, Steinbach WJ. Differential Effects of Inhibiting Chitin and 1,3-{beta}-D-Glucan Synthesis in Ras and Calcineurin Mutants of Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:476-82; PMID:19015336; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/AAC.01154-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Espinel-Ingroff A, Rezusta A. E-Test Method for Testing Susceptibilities of Aspergillus spp. to the New Triazoles Voriconazole and Posaconazole and to Established Antifungal Agents: Comparison with NCCLS Broth Microdilution method. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:2101-7; PMID:12037072; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2101-2107.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Yelton MM, Hamer JE, Timberlake WE. Transformation of Aspergillus nidulans by using a trpC plasmid. PNAS 1984; 81:1470-4; PMID:6324193; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Al Abdallah Q, Norton TS, Hill AM, LeClaire LL, Fortwendel JR. A Fungus-Specific Protein Domain is essential for RasA-Mediated Morphogenetic signaling in Aspergillus fumigatus. mSphere 2016; 1 (6):e00234-16; PMID:27921081; https://doi.org/ 10.1128/mSphere.00234-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.