Abstract

Rationale: Sleep disturbance during intensive care unit (ICU) admission is common and severe. Sleep disturbance has been observed in survivors of critical illness even after transfer out of the ICU. Not only is sleep important to overall health and well being, but patients after critical illness are also in a physiologically vulnerable state. Understanding how sleep disturbance impacts recovery from critical illness after hospital discharge is therefore clinically meaningful.

Objectives: This Systematic Review aimed to summarize studies that identify the prevalence of and risk factors for sleep disturbance after hospital discharge for critical illness survivors.

Data Sources: PubMed (January 4, 2017), MEDLINE (January 4, 2017), and EMBASE (February 1, 2017).

Data Extraction: Databases were searched for studies of critically ill adult patients after hospital discharge, with sleep disturbance measured as a primary outcome by standardized questionnaire or objective measurement tools. From each relevant study, we extracted prevalence and severity of sleep disturbance at each time point, objective sleep parameters (such as total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and arousal index), and risk factors for sleep disturbance.

Synthesis: A total of 22 studies were identified, with assessment tools including subjective questionnaires, polysomnography, and actigraphy. Subjective questionnaire studies reveal a 50–66.7% (within 1 mo), 34–64.3% (>1–3 mo), 22–57% (>3–6 mo), and 10–61% (>6 mo) prevalence of abnormal sleep after hospital discharge after critical illness. Of the studies assessing multiple time points, four of five questionnaire studies and five of five polysomnography studies show improved aspects of sleep over time. Risk factors for poor sleep varied, but prehospital factors (chronic comorbidity, pre-existing sleep abnormality) and in-hospital factors (severity of acute illness, in-hospital sleep disturbance, pain medication use, and ICU acute stress symptoms) may play a role. Sleep disturbance was frequently associated with postdischarge psychological comorbidities and impaired quality of life.

Conclusions: Sleep disturbance is common in critically ill patients up to 12 months after hospital discharge. Both subjective and objective studies, however, suggest that sleep disturbance improves over time. More research is needed to understand and optimize sleep in recovery from critical illness.

Keywords: sleep quality, insomnia, sleep wake disorders, critical illness, patient discharge

Sleep is critical for health and well being. High-quality, efficient sleep of adequate duration helps to consolidate memory, regulate the immune system, and coordinate neuroendocrine function (1–3). Abnormalities in sleep, by contrast, are thought to increase the risk of a broad range of adverse health effects, including cardiovascular disease, depression, cognitive impairment, seizures, and even overall mortality (4–8).

Sleep disturbance is particularly pronounced in the intensive care unit (ICU). Critically ill patients experience intersecting factors of pre-existing sleep disorders, acute severe illness, sleep-altering medical interventions, and the disruptive ICU environment (9). Surveys of ICU patients show that self-reported sleep disturbance is common, in some cases being reported by 100% of patients (10–12). In quantitative studies of sleep, ICU patients show reduced sleep efficiency, reduced slow-wave and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, increased daytime sleep, and significant sleep fragmentation (3, 13, 14). As a consequence, poor sleep in the ICU is believed to contribute to adverse hospital outcomes, including delirium, poor respiratory function, aberrant immune system activation, and increased mortality (3, 15–17).

Although there is evidence that critically ill patients have persistent sleep disturbances after transfer from the ICU to other floors, less is known about the lasting impacts of critical illness after hospital discharge (18–21). In qualitative interview studies, critical illness survivors commonly describe sleep difficulties, including themes of “longing for normal sleep” and “being tormented by nightmares” after hospital discharge (22, 23). Given the vulnerable state of patients after critical illness, it is important to understand how poor sleep after hospital discharge may impact recovery (24). The aim of this Systematic Review is to identify studies describing the prevalence of and risk factors for sleep disturbance in critically ill patients after hospital discharge.

Methods

We used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines as a model for conducting this Systematic Review (25, 26). Specifically, our Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome (PICO) question was framed as: “What is the prevalence of and risk factors for sleep disturbance (O) in posthospitalization patients (P) who were admitted to an ICU for critical illness (I)”. Given the nature of our desired outcomes, no control group (C) was required. We define “sleep disturbance” as sleep that is abnormal in timing, quality, or quantity and/or sleep that is insufficient for normal daily function.

We conducted our search through the following electronic databases: PubMed (no date restrictions, final search on January 4, 2017), MEDLINE (1946–present, final search on January 4, 2017), and EMBASE (1974–present, final search on February 1, 2017). We included original articles assessing posthospitalization sleep for at least one time point in patients who experienced medical critical illness. Our inclusion criteria required that a study either: (1) subjectively assess sleep through a standardized questionnaire measure; or (2) use objective sleep assessment tools (such as polysomnography [PSG] or actigraphy) and report general sleep parameters, such as total sleep time, sleep efficiency, or arousal index.

We excluded studies focused primarily on patients with postoperative, burn injury, or acute neurologic injury (such as traumatic brain injury or stroke). We excluded studies without measurements after hospital discharge, studies using only open-ended interviews to assess sleep, nonadult studies, non-English publications, review articles, editorials, case reports, and abstracts.

Search Terms

The following search terms and medical subject headings were used to capture sleep studies: “sleep disturbance,” “sleep quality,” “sleep wake disorders,” “dyssomnias,” “sleep disorders, circadian rhythm,” “sleep deprivation,” “insomnia,” and “chronobiology disorders.” Posthospitalization patients were captured by the following search terms and medical subject headings: “critical illness,” “critically ill,” “intensive care unit(s),” “patient discharge,” “critical care,” “ICU,” “post-ICU,” “hospital discharge,” and “post-hospital.” Results from each database were imported into a citation manager (EndNote X7). Each reference was reviewed (title, abstract, full text if necessary) to determine eligibility. We also searched reference lists of articles obtained through our primary search for additional relevant articles. Search results were screened by one reviewer (M.T.A.) and resulting full-text articles were independently evaluated for inclusion by three reviewers (M.T.A., M.A.P., M.P.K.); disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (M.T.A.).

We extracted from each article its study design, patient characteristics, sample size, and sleep assessment tool. For each study, we recorded prevalence and severity of sleep disturbance with associated time point, objective PSG and actigraphy measurements, and risk factors for sleep disturbance.

Results

Study Inclusion, Characteristics, and Sources of Bias

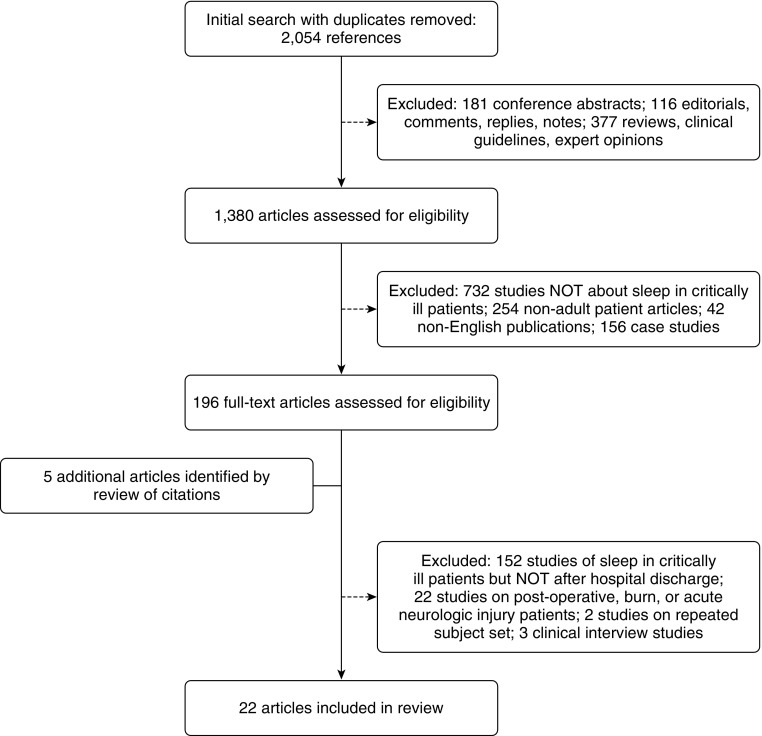

The results of our literature search are shown in Figure 1. Our initial search revealed 2,054 unique citations. Screening of these citations identified 17 studies that assessed sleep in critically ill patients after hospital discharge (27–43). An additional 5 studies were identified through searching reference lists, yielding a total of 22 articles reviewed (44–48).

Figure 1.

Results of literature search (PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE).

Of the 22 included studies, 21 were prospective cohort studies (2 as a secondary analysis) and 1 was a cross-sectional study. There were no randomized, controlled trials. Given the descriptive nature of these studies, the major outcome-level biases of measuring post-ICU sleep disturbance prevalence were: (1) information bias from variations in assessment tools (Table 1); and (2) attrition bias from loss to follow-up (Table 2).

Table 1.

Subjective sleep questionnaires

| Assessment Tool | No. of Sleep Items | Scale | Domains | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSQI (50, 52) | 19 | Four-point scale, free response for sleep parameters | Sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep disturbance, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep medication use, and daytime dysfunction | Component scores for each domain sum to one “global” score (0–21). Scores >5 have 89.6% sensitivity and 86.5% specificity for distinguishing “good and poor sleepers.” |

| ESS (51, 52, 54) | 8 | Four-point scale | Daytime sleepiness | Patient rates their likelihood of falling asleep during eight common daily activities (e.g. sitting and reading). Validated in numerous sleep and neurologic disorder populations. |

| BNSQ (33, 52, 53) | 27 | Five-point scales, free response for sleep parameters | Apnea, sleep duration, sleep medication use, daytime sleepiness/napping, snoring | Developed from existing sleep apnea questionnaires in Scandinavia. Not assessed for reliability or interpretability. |

| FOSQ (31, 52, 57) | 30 | Four-point scale ranging from “no difficulty” to “extreme difficulty” | HRQoL resulting from excessive sleepiness | Assesses how daytime sleepiness affects patient’s ability to perform daily activities. Items combine for overall score of 5–20. Limited data on interpretability; however, score cutoffs of <17.9 have been used to indicate poor sleep-related quality of life. |

| ISI (38, 49, 65) | 7 | Five-point scale | “Sleep-onset and maintenance issues, satisfaction with current sleep pattern, interference with daily function, noticeability of impairment attribute to sleep problem, and degree of distress caused by the sleep problem” | Assesses insomnia symptoms and consequences on daily functioning; items tailored to DSM-IV and ICSD diagnostic criteria for insomnia. Overall score ranges from 0 to 28; >14 indicates clinical insomnia. In a community sample, scores >10 were 86.1% sensitive and 87.7% specific for insomnia. |

| 15D HRQoL (30, 66) | 1 | Five-point scale | One sleep item included in broader assessment tool of HRQoL. Sleep quality rated from “I am able to sleep normally” to “I suffer severe sleeplessness” | |

| Modified Given Symptom Assessment Tool (32, 67) | 1 | Yes/no response, with 10-point severity scale if answered “yes” | “Disturbed sleep” | Assesses self-reported physical symptoms in ICU patients by asking about presence and severity of common symptoms. This new tool was developed by Choi and colleagues (32) and has not been validated for ICU patients. |

| NHP (41, 46, 55) | 5 | Five weighted items | HRQoL for sleep | Measures HRQoL across six domains, one of which is sleep; five weighted items sum to 0–100 score, with higher scores indicating worse function. |

| PTSD PCL (35) | 1 | One- to five-point severity scale | One sleep item included in broader PTSD assessment. Parsons and colleagues in 2012 (35) used one question “In the last month, how much have you been bothered by trouble falling or staying asleep?” to assess insomnia | |

| Verran and Snyder-Halpern Sleep Scale (34, 52, 56) | 15 | A 0- to 100-point visual-analog scale | Sleep disturbance, effective sleep, supplementary sleep | Assesses sleep quality over previous 3 night’s sleep; reliable and valid in hospitalized patients |

Definition of abbreviations: BNSQ = Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV; ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale; FOSQ = Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; ICSD = International Classification of Sleep Disorders; ICU = intensive care unit; ISI = Insomnia Severity Index; NHP = Nottingham Health Profile; PCL = post-traumatic stress disorder checklist; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 2.

Prevalence of subjective sleep disturbances after hospital discharge

| Study (First Author, Year [Ref. No.]) | Design and Sample Characteristics | Sample Size and Attrition | Assessment tool | Result (Time from Hospital Discharge) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eddleston, 2000 (27) | Prospective cohort | n = 143 enrolled (3 mo) | Original questionnaire | 34% (3 mo)* |

| Discharged ICU patients, no exclusion criteria | n = 143 (12 mo) | 16% (12 mo)* | ||

| 37% of ICU survivors declined participation | ||||

| Combes, 2003 (41) | Prospective cohort | n = 87 (median 3 yr) | Nottingham Health Profile† | 33 mean sleep score (3 yr)*‡ |

| Mechanically ventilated patients | 12% lost to follow-up | |||

| Granja, 2005 (37) | Prospective cohort | n = 464 (6 mo) | Original questionnaire | 41% (6 mo)* |

| Post-ICU patients responding to mail-out questionnaire | 49% nonresponse rate | |||

| Orwelius 2008 (33) | Prospective cohort | n = 911 (6 mo) | Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire | 20% poor sleep quality (6 mo) |

| MICU/SICU patients | n = 497 (Both 6 and 12 mo; 188 excluded, 226 nonparticipants) | 38% difficulty falling asleep (6 mo) | ||

| 44% lost to follow-up before 6 mo | 61% perceived sleep deficit (6 mo) | |||

| No significant changes by 12 mo | ||||

| Cronberg, 2009 (42) | Prospective cohort | n = 43 (mean, 7.2 mo) | Skane Sleep Index§ | 22% insomnia (mean, 7.2 mo) |

| ICU patients with cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia | 14% of survivors declined assessment | 10% poor sleep quality (mean, 7.2 mo) | ||

| 6.5% daytime sleepiness (mean, 7.2 mo) | ||||

| Kelly and McKinley, 2010 (36) | Prospective cohort | n = 39 (mean, 12.5 wk) | Original questionnaire (either in-person or by telephone) | “Half” (mean 12.5 wk) |

| Medical, surgical, cardiothoracic, and neurological ICU patients | 33% nonparticipation of survivors contacted by telephone | |||

| Masclans, 2011 (45) | Prospective cohort | n = 38 (6 mo) | Nottingham Health Profile† | 20 mean sleep score (6 mo from admission) |

| Patients with ARDS | 57% exclusion/loss to follow-up of survivors | |||

| McKinley, 2012 (30)|| | Prospective cohort | n = 195 enrolled | 15D HRQoL | 50% (1 wk) |

| Mechanically ventilated MICU/SICU patients in an RCT for post-ICU home-based rehabilitation | n = 186 (1 wk) | 35% (8 wk) | ||

| n = 175 (8 wk) | 31% (26 wk) | |||

| n = 164 (26 wk) | ||||

| 16% died/lost to follow-up by 26 wk | ||||

| Parsons, 2012 (35)¶ | Prospective cohort, secondary analysis | n = 40 (6 mo) | Post-traumatic stress disorder checklist | 50% (6 mo) |

| Acute lung injury, mechanically ventilated patients | 15% nonresponse in eligible survivors | |||

| McKinley, 2013 (29) | Prospective cohort | n = 222 enrolled in ICU | Richards Campbell Sleep Questionnaire, PSQI | 73% in ICU, 68% in hospital ward |

| General, cardiothoracic, and neurological ICU patients | n = 199 (hospital ward) | 62% (2 mo) | ||

| n = 183 (2 mo) | 57% (6 mo) | |||

| n = 179 (6 mo) | ||||

| 19% attrition from ICU to 6-mo follow-up | ||||

| Choi, 2014 (32) | Prospective cohort | n = 47 enrolled in ICU | Modified Given Symptom Assessment Tool | 66.7% (2 wk) * |

| Mechanically ventilated MICU patients | n = 39 (2 wk) | 64.3% (2 mo)* | ||

| n = 31 (2 mo) | 46.2% (4 mo)* | |||

| n = 27 (4 mo) | ||||

| 43% attrition at 4 mo | ||||

| Parsons, 2015 (38) | Prospective cohort, cross-sectional secondary analysis | n = 120 (12 mo) | Insomnia Severity Index | 28% (12 mo) * |

| MICU/SICU patients | 7% died from ICU enrollment, 13% unavailable/withdrew | |||

| Dhooria, 2016 (31)** | Prospective cohort | n = 20 (1 mo) | PSQI, ESS, FOSQ, PSG | 50% (1 mo)* |

| Patients with ARDS in respiratory ICU | Five patients refused consent | |||

| Solverson, 2016 (40) | Prospective cohort | n = 56 (1 mo) | PSQI, ESS | 62% poor sleep quality (3 mo) |

| MICU/SICU patients | All underwent questionnaire testing | 23% daytime sleepiness (3 mo) |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale; FOSQ = Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire; HRQoL = health-related quality of life; ICU = intensive care unit; MICU = medical intensive care unit; PSG = polysomnography; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; RCT = randomized, controlled trial; SICU = surgical intensive care unit.

Time measured from ICU discharge (rather than hospital discharge)

Reports sleep score on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating worse disturbance.

Estimated value from bar graph within article.

This tool is a “locally modified” version of the PSQI for use in Sweden.

Reports prevalence of “moderate to severe sleep problems”

Measuring prevalence of self-reported insomnia.

Using a composite criterion incorporating both subjective and objective measures, with sleep disturbance defined as abnormalities in at least one measurement tool.

Subjective Studies of Sleep in Critically Ill Patients

Of the 22 included studies, 17 used standardized questionnaires to assess subjective sleep disturbance after critical illness (27, 29–42, 45, 46). These studies vary widely in tools used, ranging from original questionnaires, to quality of life tools, to validated sleep surveys (Table 1) (49–51).

These subjective tools can be categorized into three groups. Some tools broadly assess sleep across its fundamental domains, such as sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, sleep quality, and daytime somnolence—these include the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ) (50, 52, 53). Several other instruments emphasize just one or several of these aspects of sleep—for example, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, the Verran and Snyder-Halpern Sleep Scale, and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (49, 51, 52, 54–56). Finally, some questionnaires assess the functional effects of sleep disturbance on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), such as the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire and Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) (52, 55, 57). Although the PSQI overall is the most widely used and well validated, none of these tools has been validated in critically ill populations.

Prevalence of Sleep Disturbance after Hospitalization

Subjective questionnaire studies that measure the prevalence of sleep disturbance (14 studies) are summarized in Table 2.

Three studies assessed sleep within 1 month after hospitalization, when the prevalence of sleep disturbance ranged from 50 to 66.7% (30–32). Five studies assessed sleep at over 1 month to 3 months after hospitalization or ICU stay, and showed a 34–64.3% prevalence of abnormal sleep (27, 29, 30, 32, 40). In one of these studies, 23% of patients additionally reported significant daytime sleepiness (40). The most common time studied was over 3 to 6 months after hospitalization or ICU stay (eight studies), in which the prevalence of sleep disturbance ranged from 22 to 57% of patients (29, 30, 32, 33, 35–37, 45). In five studies with over 6-month follow-up, the prevalence of sleep disturbance was 10–61% (27, 33, 38, 41, 42).

Three questionnaire-based studies compared post-ICU patients to a reference population (33, 41, 45). Orwelius and colleagues (33) assessed sleep posthospitalization in a subset of 1,625 ICU patients in Sweden and compared them to a group of 10,000 community-dwelling people from the hospital intake area. Compared with the reference group, the post-ICU sample self-reported greater difficulty falling asleep (38 vs. 13%), worse sleep quality (20 vs. 12%), and greater sleep deficit (61 vs. 55%) 6 months after hospital discharge. Similarly, Combes and colleagues (41) reported on a subset of 347 mechanically ventilated ICU patients (n = 87) who completed the NHP quality of life tool at 3 years post-ICU. They determined the mean sleep score after hospitalization to be significantly worse than in a community-based population of age- and sex-matched control subjects with no significant illnesses. In contrast, Masclans and colleagues (45) found that the average NHP sleep score for 38 patients with ARDS 6 months after ICU admission was the same compared with a healthy Barcelona reference population (P = 0.364).

Changes in Prevalence of Subjective Sleep Disturbance over Time

Five of the questionnaire studies assess sleep at multiple time points after hospitalization (27, 29, 30, 32, 33). Over time after hospitalization, sleep disturbance either improved (four studies) or remained stable in prevalence (one study) (Table 2). For example, in 2012, McKinley and colleagues (30) assessed psychological outcomes in 195 ICU patients after hospital discharge, and found that 50% of patients had moderate to severe sleep disturbance (by a five-point sleep item from the 15D HRQoL instrument) at 1 week, whereas 31% of patients had this degree of poor sleep at 26 weeks. Similarly, Choi and colleagues (32) studied 47 mechanically ventilated medical ICU survivors, and identified self-reported sleep disturbance in 66.7, 64.3, and 46.2% of patients at 2 weeks, 2 months, and 4 months after ICU discharge, respectively. The severity of sleep disturbance, however, did not change over time.

Two studies that assessed sleep at multiple time points included an assessment of prehospitalization sleep. Orwelius and colleagues (33) found that 21% of patients had poor sleep quality prehospitalization, and 22% of these patients reported poor sleep quality at 6 months posthospitalization using the BNSQ. Notably, baseline sleep dysfunction was gathered by asking patients at 6-month follow-up to retrospectively assess their prehospitalization sleep using a single BNSQ sleep question. The second study, by McKinley and colleagues in 2013 (29), assessed sleep in 222 mixed-ICU patients across five time points: once prehospital (using the ISI retrospectively upon admission), twice within the hospital (using the Richards Campbell Sleep Questionnaire), and at 2 and 6 months posthospitalization (using the PSQI). A total of 18% of patients had prehospital insomnia, 62% had poor sleep quality at 2 months, and 57% had poor sleep quality at 6 months. Only 10%, however, had poor sleep at all time points during and after ICU stay (29).

Objective Studies of Sleep in Critically Ill Patients

Eight studies used objective measures to quantify sleep disturbance parameters in post-ICU patients (Table 3) (28, 31, 39, 40, 43, 44, 47, 48). Six of these studies used PSG (3), one used actigraphy, and one used portable sleep study. Actigraphy is accomplished with a small device worn on the wrist or ankle with internal accelerometer that is validated to measure rest–wake patterns via body movement (3, 40, 58).

Table 3.

Studies using objective measures of sleep

| Study (No. of Patients) | Measure Time from Hospital Discharge | TST (h) | Sleep Efficiency (%) | Arousal Index | Sleep Onset Latency (min) | SWS (%) | REM (%) | AHI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skinner, 2005 (43) | Portable sleep study admission | 22.4 ± 20.3 | ||||||

| n = 18 CCU patients with ACS or LV failure | Portable sleep study >6 wk | 13.3 ± 12.8 | ||||||

| BaHammam, 2005 (48) | PSG 3 d | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 62.3 ± 4.6 | 40.3 ± 3.7 | 41.5 ± 4.2 | |||

| n = 21 ACS CCU patients with AHI>10 on first PSG* | PSG 6 mo | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 80.9 ± 4.2 | 21.9 ± 2.1 | 30.3 ± 4.7 | |||

| BaHammam, 2006 (28) | PSG 3 d | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 61 | 44.8 ± 4.5 | 24.9 ± 3.8 | 10 | 10 | |

| n = 20 First time ACS CCU patients* | PSG 6 mo | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 82 | 25.3 ± 3.9 | 19.6 ± 4.8 | 8 | 16 | |

| Lee, 2009 (39) | PSG >6 mo | 5.8 | 80.2 | 16.2 | 14.9 | 23.5 | 19.7 | 1.8 |

| n = 7 patients with ARDS with self-reported sleep disturbance† | ||||||||

| Schiza, 2010 (44) | PSG 3 d | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 59.8 ± 10.1 | 26.6 ± 11.9 | 52.5 ± 13.4 | 5.4 ± 2.1 | 3.1 ± 3.9 | 4.9 ± 1.9 |

| n = 22 First-time ACS CCU patients‡ | PSG 1 mo | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 74.5 ± 6.1 | 13.4 ± 6 | 35.7 ± 10.8 | 10.3 ± 2.6 | 10.9 ± 3.5 | 4.1 ± 1.5 |

| PSG 6 mo | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 82.6 ± 5.9 | 3.9 ± 1.9 | 21.7 ± 7.9 | 12.8 ± 2.5 | 13.1 ± 2.8 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | |

| Schiza, 2012 (47) | PSG 3 d | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 62.3 ± 9.6 | 26.9 ± 10.9 | 5.5 ± 2.1 | 2.4 ± 2.9 | 19.7 ± 6.9 | |

| n = 28 First time ACS CCU patients with AHI>10 on first PSG‡ | PSG 1 mo | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 75.9 ± 7.9 | 12.9 ± 3.8 | 10.7 ± 2.1 | 11.0 ± 1.3 | 13.9 ± 5.9 | |

| PSG 6 mo | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 83.8 ± 5.6 | 4.3 ± 3.5 | 13.7 ± 3.2 | 13.6 ± 3.7 | 7.5 ± 4.6 | ||

| Dhooria, 2016 (31) | PSG | 4.64 (3.6–6.4) | 54 (32.3–65.4) | 21.5 (8.4–61.0) | 15.9 (8.4–24.1) | 5.5 (2.3–15.1) | 1.9 (0.7–2.7) | |

| n = 20 patients with ARDS§ | 1 mo post-ICU | |||||||

| Solverson, 2016 (40) | Actigraphy 3 mo | 6.2 ± 3.4 | 78 ± 18 | 11 ± 5 awakenings per night | 12 ± 11 | |||

| n = 11 MICU/SICU patients |

Definition of abbreviations: ACS = acute coronary syndrome; AHI = apnea–hypopnea index; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CCU = coronary care unit; LV = left ventricle; MICU = medical intensive care unit; PSG = polysomnography; REM = rapid eye movement; SICU = surgical intensive care unit; SWS = slow wave sleep; TST = total sleep time.

Values reported as mean ± SD except where indicated.

These studies compared PSG parameters at 3 d and 6 mo post-ACS event. BaHammam, 2005 (48): P ≤ 0.01 for differences in TST, sleep efficiency, and arousal index; BaHammam, 2006 (28): P < 0.05 for differences in sleep efficiency, REM sleep %, TST, and arousal index. Sleep efficiency, SWS %, and REM % estimated from bar graphs in article. Values reported as mean ± SE.

Median values; variance values not reported.

These studies compared PSG parameters at 3 d, 1 mo, and 6 mo post-ACS event. P < 0.05 for total sleep time, sleep efficiency, arousal index, sleep latency, slow wave sleep %, REM sleep %, and AHI in both studies (with significant improvements in these parameters across time).

§Values reported as median (interquartile range).

Lee and colleagues (39) used PSG to describe sleep in seven survivors of ARDS who reported persistent sleep difficulties at least 6 months posthospitalization. Each patient was diagnosed with a primary sleep disorder—five with conditioned insomnia, one with obstructive sleep apnea, and one with parasomnia. Dhooria and colleagues similarly studied 20 patients with ARDS 1 month post-ICU with PSG and clinical sleep evaluation, and found that 50% met their composite criterion for sleep disturbance—of these, four had insomnia, two central sleep apnea, one obstructive sleep apnea, and one REM sleep–disordered breathing (two with subjective “abnormal sleep” had normal PSG) (31). These patients also showed poor sleep efficiency (54% [interquartile range = 32.3–65.4]), with low percentages of slow-wave and REM sleep.

Five studies assessed patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) at various time points during and after coronary care unit (CCU) admission (28, 43, 44, 47, 48). Both BaHammam in 2006 (28) and Schiza and colleagues in 2010 (44) performed PSG during acute CCU admission, but in a removed sleep center to reduce the contribution of environmental factors to poor sleep. Each group also separately studied patients with ACS who had sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) on an admission PSG (47, 48). All four of these studies found that objective sleep parameters were significantly disturbed on admission, with significant improvement on follow-up PSGs—in the study by Schiza and colleagues in 2010 (44), for example, patients gradually returned to normal sleep architecture 6 months after ACS (28, 44, 47, 48). Similarly, Skinner and colleagues (43) observed a 50% decrease in SDB prevalence in CCU patients undergoing sleep study, both at admission and at 6 week follow-up.

Using multinight actigraphy, Solverson and colleagues (40) assessed sleep in 11 critical illness survivors 3 months after hospitalization, excluding patients with various acute or chronic neurologic deficits. Overall, patients had an average sleep time of 6.15 h/night and sleep efficiency of 78%, which the authors suggested were lower than expected compared with normal subjects (by 1 h and 10%, respectively).

Risk Factors for Disturbed Sleep

Studies assessing risk factors for post-ICU sleep disturbance are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Risk factors and metrics associated with poor sleep after discharge

| Study (First Author, Year [Ref. No.]) | Risk Factors and Metrics (HRQoL, Psychological Factors) |

Independent Predictors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prehospital | In-Hospital | Posthospital | ||

| Niskanen, 1999 (46) | Older age (P < 0.01) | Open heart surgery (P < 0.01)* | ||

| Respiratory failure (P < 0.01)* | ||||

| Eddleston, 2000 (27) | Female sex (P = 0.022) | |||

| Combes, 2003 (41) | ARDS (P = 0.04)† | |||

| Granja, 2005 (37) | Female sex‡ | EQ-5D, all dimensions‡ | ||

| Older age‡ | ||||

| Retirement‡ | ||||

| Orwelius, 2008 (33) | Concurrent disease (P < 0.001) | SF-36 bodily pain (P = 0.002)§ | All factors were adjusted for age and sex | |

| SF-36 vitality (P < 0.001)§ | ||||

| SF-36 mental health (P < 0.001) § | ||||

| McKinley, 2012 (30) | SF-36 MCS (P = 0.0005) | |||

| DASS-21 depression, anxiety, stress (each P = 0.0005) | ||||

| Impact of events scale (P = 0.003) | ||||

| Parsons, 2012 (35) | SF-36 PCS (P < 0.01) | SF-36 PCS (P < 0.01)|| | ||

| SF-36 MCS (P = 0.01) | ||||

| McKinley, 2013 (29) | Prehospital insomnia (P = 0.0005) | RCSQ hospital sleep quality (P = 0.044) | DASS-21 depression, anxiety, stress (each P = 0.0005) | Pre-hospital insomnia (P = 0.005) |

| Home sleep quality (P = 0.0005) | ICEQ awareness of surroundings in ICU (P = 0.002) | PCL-S PTSD (P = 0.0005) | RCSQ hospital sleep quality (P = 0.025) | |

| Pain 0–10 (P = 0.043) | SF-36 PCS (P = 0.0005) | Anxiety at 6 mo (P = 0.011) | ||

| RASS score (P = 0.005) | SF-36 MCS (P = 0.0005) | SF-36 PCS (P = 0.0005) | ||

| SF-36 MCS (P = 0.0005) | ||||

| Choi, 2014 (32) | Pain severity (P < 0.05) | |||

| Fatigue severity (P < 0.05) | ||||

| Chen, 2015 (34) | Older age (P = 0.004) | APACHE II score (P < 0.001) | Post-discharge use of hypnotic drugs (P = 0.002) | APACHE II (P = 0.001) |

| No. of chronic diseases (P = 0.025) | Postdischarge use of hypnotic drugs (P = 0.001) | |||

| Prior use of hypnotic drugs (P = 0.003) | 3-4 chronic diseases (P = 0.014) | |||

| Parsons, 2015 (38) | Baseline SF-12 MCS (P = 0.02) | Substantial acute stress symptoms (P = 0.02) | Substantial PTSD symptoms (P < 0.01) | HRQoL measures lose significance when adjusting for post-ICU PTSD and depressive symptoms¶ |

| Opiate days (P = 0.03) | Substantial depressive symptoms (P < 0.01) | |||

| Solverson, 2016 (40) | APACHE II score (P = 0.019) | Anxiety (P = 0.001) | Multivariate regression with age, comorbidities, anxiety/depression did not change significance of univariates | |

| EQ-5D Mobility (P = 0.002) | ||||

| EQ-5D VAS (P = 0.003) | ||||

| SF-36 PCS (P = 0.004) | ||||

| SF-36 MCS (P = 0.002) | ||||

Definition of abbreviations: APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Score; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; DASS-21 = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale; EQ-5D VAS = EuroQol-5D visual analog scale (patient perspective of overall health); HRQoL = health-related quality of life; ICEQ = Intensive Care Experience Questionnaire; ICU = intensive care unit; MCS = Mental Composite Score (for HRQoL); PCL-S = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist; PCS = Physical Composite Score; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; RASS = Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale; RCSQ = Richards Campbell Sleep Questionnaire; SF-36 = Short-Form 36 (for HRQoL).

Worse sleep disturbances compared to neurosurgical patients.

Compared to other types of ICU patients.

Reported as significant associations, but P values not provided.

Associations with “poor quality of sleep” metric in the study.

After adjustment for PTSD (PCL score) and depression (PHQ-9 score).

Including MCS, bodily pain, vitality, and physical function SF-12 scores.

Nonmodifiable risk factors associated with poor posthospital sleep included female sex and increased age (27, 34, 37, 46). Race and ethnicity data were explicitly reported in only four studies with predominantly white samples—one study calculated no difference in insomnia rates between white and nonwhite groups (32, 35, 38, 43).

In terms of prehospitalization risk factors, only the 2013 study by McKinley and colleagues (29) analyzed prehospital sleep using ISI insomnia scores, which were independently associated with poorer sleep at 6 months after hospitalization. Orwelius and colleagues (33) noted that self-reported concurrent disease before hospitalization (inquiring about numerous chronic conditions) was a significant driver of poor sleep (odds ratio of 2.51 for poor sleep quality at 6-mo follow-up; P < 0.001). Chen and colleagues (34) similarly found that increasing number of chronic diseases (at least three to four; P = 0.014) independently predicted poor sleep quality in respiratory care center patients being weaned from mechanical ventilation. In contrast, Solverson and colleagues (40) found no association between pre-existing comorbidity (cancer, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes) and sleep quality 3 months after discharge. Parsons and colleagues in 2012 (35) also did not identify an association of baseline smoking, chronic health problems, or psychiatric disorders with postdischarge insomnia.

Several studies analyzed the effects of in-hospital factors, such as Acute Physiology and Chronic Health (APACHE) scores (a measure of disease severity), ventilator days, ICU and hospital length of stay, and ICU medication use. In these studies, sleep disturbance was associated with having poor sleep quality in the hospital ward (but not in the ICU for the same study), APACHE II scores, ICU acute stress symptoms, and total days of hospital opioid use (29, 34, 38, 40). Three studies, however, found no association between various in-hospital factors and poor post-ICU sleep, including ICU and hospital length of stay, APACHE scores, admission diagnosis, or mechanical ventilation days (29, 33, 35).

Posthospital factors associated with poor sleep after discharge were primarily assessed using validated questionnaires focusing on HRQoL measures and psychological factors (depression, anxiety, stress; Table 4). Many of these scores were found to be independent predictors of poor sleep after discharge.

Specific Patient Populations

Chen and colleagues (34) retrospectively assessed predictors of poor sleep quality in 94 patients undergoing weaning from mechanical ventilation in a specialized respiratory care center in Taiwan. Their regression analysis demonstrated that disease severity (APACHE II, P = 0.001), current use of hypnotic drugs (P = 0.001), and increasing number of chronic diseases (P = 0.014) independently predicted poor sleep quality.

Cronberg and colleagues (42) assessed neurologic outcomes in 43 survivors of cardiac arrest who underwent therapeutic hypothermia. Using the Skane Sleep Index (a modified version of the PSQI), they found that 22% of patients had frequent insomnia symptoms, 10% experienced poor sleep quality, and 6.5% had excessive daytime sleepiness at mean 7.2-month follow-up after cardiac arrest.

Discussion

This Systematic Review identified 22 articles assessing sleep disturbance in critically ill patients after hospitalization. These studies vary widely in their sample numbers, patient characteristics, time to follow-up, and assessment tools, the latter of which may particularly limit comparison across studies given the numerous domains of sleep. Nonetheless, these studies together help to clarify the effects of critical illness on sleep during recovery. Such understanding can be important, as sleep disturbance is a potential component of the posthospital syndrome that leaves patients in a physiologically vulnerable state after discharge (24).

These studies suggest that the prevalence of sleep disturbance in post-ICU patients is high—ranging from 50 to 66.7% in the first month after hospital discharge and 22–57% at 3 months or longer to 6 months after hospital discharge, with two studies suggesting that these rates are significantly higher than in the general population. In the subjective studies that measured sleep at multiple time points, however, four of five showed improvements in sleep disturbance over time (27, 29, 30, 32, 33). This is reinforced by several studies measuring objective sleep parameters, which showed a significant improvement in sleep parameters over time after discharge (28, 44, 47, 48).

Notably, two objective studies found a high rate of SDB in patients with ACS, which decreased in prevalence over time after discharge coincident with improvement in other objective sleep parameters (43, 47). Thus, improvement in SDB may provide one potential mechanism by which subjective sleep disturbance improves over time. Cardiac disease and ACS, however, are strongly associated with SDB, and thus generalization to other critically ill populations is limited.

Given the likely multifactorial etiology of sleep disturbance in critically ill patients, it is important to assess pre-existing sleep disturbance before ICU stay. Orwelius and colleagues (33) reported no change in the prevalence of poor sleep quality between pre-ICU and 6 months after ICU stay (21 and 22%, respectively). This study, however, retrospectively assessed prehospital sleep at 6-month follow-up, and thus their results may be particularly subject to recall bias. McKinley and colleagues (29), on the other hand, determined that 18% of their ICU patients met prehospital insomnia criteria upon admission, whereas 62 and 57% at 2 and 6 months, respectively, had poor sleep quality by PSQI criteria. Interpretation of these results, however, is constrained by the use of different sleep assessment tools across time.

Analyses of risk factors for post-ICU sleep disturbance are conflicting. Three of five studies suggest that pre-ICU factors contribute to posthospital sleep disturbance, with prehospital insomnia scores (29) and chronic comorbidities (33, 34) being associated with poor sleep outcomes. The other two studies found no such relationships, though their definitions of comorbidity were narrower or poorly defined (35, 40). Notably, two studies identified sex as a nonmodifiable factor associated with poor posthospital sleep (27, 37). Sex differences have been observed for sleep in the literature—for example, healthy men and women differ in their sleep duration, quality, and architecture, as well as in rates of insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (59). Men and women also appear to respond differently to acute sleep debt, such as what might occur in critical illness (60, 61).

Regarding in-hospital factors, two studies found that APACHE II scores (34, 40) predicted poor posthospital sleep, whereas three studies did not find any contribution of in-ICU factors to poor sleep outcomes (29, 33, 35). Other important in-hospital factors associated with posthospital sleep disturbance were sleep quality on the hospital ward (29), ICU acute stress symptoms (38), and days of hospital opioid use (38). These findings suggest that there are potentially modifiable risk factors during hospitalization that can be targeted to limit poor sleep after discharge.

Several studies demonstrate abundant associations between postdischarge sleep disturbance and multiple poor quality-of-life domains, including physical and mental health, fatigue, mobility, and self-care (29, 30, 32, 33, 35, 37, 40). In several cases, postdischarge psychological comorbidities (anxiety, depression, and stress) were also significantly associated with sleep disturbance and quality-of-life impairment (29, 30, 38, 40). There is likely to be, however, some overlap and confounding in the measurement and diagnosis of these entities—for example, in the 2015 study by Parsons and colleagues (38), quality-of-life outcomes were no longer associated with insomnia when adjusted for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms. Given their likely complex interactions, the effects of psychological comorbidity, quality of life, and sleep disturbance on post-ICU recovery warrant further investigation.

There are several potential limitations of this review. First, sleep encompasses an expansive field with potential overlap across many patient-centered outcomes. Although we did not search specifically for studies of quality-of-life or psychological outcomes, these studies could include sleep items in their measurement tools. Second, we considered studies of postoperative patients and patients with other primary surgical issues to be outside of the scope of this review, given their distinct clinical characteristics. There is, however, evidence that sleep can be impaired after discharge in these critically ill populations—for example, cardiac surgery studies have been previously reviewed (62–64). Third, we identified several articles focused on sleep after transfer out of the ICU (18–21). Although we did not review these studies, they represent potential sources for understanding the more immediate impacts of critical illness on sleep while patients are still hospitalized. Finally, the small numbers of patients, variety of instruments, and varying study quality did not allow for combining data for a meta-analysis.

Conclusions

Sleep disturbance after critical illness appears to be highly prevalent after hospital discharge, even at time points up to 1 year after hospitalization. Nonetheless, several studies suggest the potential for improvement in self-reported sleep, as well as objective sleep parameters, over time. Risk factors for poor sleep are conflicting, but there may be significant contributions of prehospitalization factors (such as chronic comorbidity and prehospital sleep disturbance) and in-hospital factors (such as acute severity of illness, sleep within hospital, pain medication use, and ICU acute stress symptoms). Given the importance of sleep to both physical and psychological well being, more research is needed to characterize sleep disturbance and risk factors for poor sleep in posthospital critically ill patients so as to minimize injury during hospitalization and optimize recovery.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This study was supported by funds from the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation (M.A.P.), CTSA grant KL2 TR000140 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (M.P.K.), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH; the contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH), and by a Yale University School of Medicine Medical Research Fellowship (M.T.A.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Stickgold R. Neuroscience: a memory boost while you sleep. Nature. 2006;444:559–560. doi: 10.1038/nature05309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibarra-Coronado EG, Pantaleon-Martinez AM, Velazquez-Moctezuma J, Prospero-Garcia O, Mendez-Diaz M, Perez-Tapia M, Pavón L, Morales-Montor J. The bidirectional relationship between sleep and immunity against infections. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:678164. doi: 10.1155/2015/678164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisani MA, Friese RS, Gehlbach BK, Schwab RJ, Weinhouse GL, Jones SF. Sleep in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:731–738. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201411-2099CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grandner MA, Sands-Lincoln MR, Pak VM, Garland SN. Sleep duration, cardiovascular disease, and proinflammatory biomarkers. Nat Sci Sleep. 2013;5:93–107. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S31063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samsonsen C, Sand T, Bråthen G, Helde G, Brodtkorb E. The impact of sleep loss on the facilitation of seizures: A prospective case-crossover study. Epilepsy Res. 2016;127:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Wu C, Gan Y, Qu X, Lu Z. Insomnia and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:375. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1075-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallicchio L, Kalesan B. Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:148–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malow BA. Sleep deprivation and epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 2004;4:193–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7597.2004.04509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knauert MP, Haspel JA, Pisani MA. Sleep loss and circadian rhythm disruption in the intensive care unit. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman NS, Kotzer N, Schwab RJ. Patient perception of sleep quality and etiology of sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1155–1162. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9806141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott R, Rai T, McKinley S. Factors affecting sleep in the critically ill: an observational study. J Crit Care. 2014;29:859–863. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Little A, Ethier C, Ayas N, Thanachayanont T, Jiang D, Mehta S. A patient survey of sleep quality in the intensive care unit. Minerva Anestesiol. 2012;78:406–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gehlbach BK, Chapotot F, Leproult R, Whitmore H, Poston J, Pohlman M, Miller A, Pohlman AS, Nedeltcheva A, Jacobsen JH, et al. Temporal disorganization of circadian rhythmicity and sleep–wake regulation in mechanically ventilated patients receiving continuous intravenous sedation. Sleep. 2012;35:1105–1114. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knauert MP, Yaggi HK, Redeker NS, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Pisani MA. Feasibility study of unattended polysomnography in medical intensive care unit patients. Heart Lung. 2014;43:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldham MA, Lee HB, Desan PH. Circadian rhythm disruption in the critically ill: an opportunity for improving outcomes. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:207–217. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gélinas C, Dasta JF, Davidson JE, Devlin JW, Kress JP, Joffe AM, et al. American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:263–306. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamdar BB, Martin JL, Needham DM, Ong MK. Promoting sleep to improve delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:2290–2291. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fanfulla F, Ceriana P, D’Artavilla Lupo N, Trentin R, Frigerio F, Nava S. Sleep disturbances in patients admitted to a step-down unit after ICU discharge: the role of mechanical ventilation. Sleep. 2011;34:355–362. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson T, Lee ER, Cameron C. Relationships among sleep dimensions and factors that impair sleep after cardiac surgery. Res Nurs Health. 1996;19:213–223. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199606)19:3<213::AID-NUR5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chishti A, Batchelor AM, Bullock RE, Fulton B, Gascoigne AD, Baudouin SV. Sleep-related breathing disorders following discharge from intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:426–433. doi: 10.1007/s001340051177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strahan E, Mccormick J, Uprichard E, Nixon S, Lavery G. Immediate follow-up after ICU discharge: establishment of a service and initial experiences. Nurs Crit Care. 2003;8:49–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1478-5153.2003.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tembo AC, Parker V, Higgins I. The experience of sleep deprivation in intensive care patients: findings from a larger hermeneutic phenomenological study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013;29:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chahraoui K, Laurent A, Bioy A, Quenot JP. Psychological experience of patients 3 months after a stay in the intensive care unit: a descriptive and qualitative study. J Crit Care. 2015;30:599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:100–102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kable AK, Pich J, Maslin-Prothero SE. A structured approach to documenting a search strategy for publication: a 12 step guideline for authors. Nurse Educ Today. 2012;32:878–886. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eddleston JM, White P, Guthrie E. Survival, morbidity, and quality of life after discharge from intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2293–2299. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.BaHammam A. Sleep quality of patients with acute myocardial infarction outside the CCU environment: a preliminary study. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:CR168–CR172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKinley S, Fien M, Elliott R, Elliott D. Sleep and psychological health during early recovery from critical illness: an observational study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:539–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKinley S, Aitken LM, Alison JA, King M, Leslie G, Burmeister E, Elliott D. Sleep and other factors associated with mental health and psychological distress after intensive care for critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:627–633. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhooria S, Sehgal IS, Agrawal AK, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Behera D. Sleep after critical illness: study of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome and systematic review of literature. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016;20:323–331. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.183908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi J, Hoffman LA, Schulz R, Tate JA, Donahoe MP, Ren D, Given BA, Sherwood PR. Self-reported physical symptoms in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors: pilot exploration over four months post-ICU discharge. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orwelius L, Nordlund A, Nordlund P, Edell-Gustafsson U, Sjoberg F. Prevalence of sleep disturbances and long-term reduced health-related quality of life after critical care: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2008;12:R97. doi: 10.1186/cc6973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen CJ, Hsu LN, McHugh G, Campbell M, Tzeng YL. Predictors of sleep quality and successful weaning from mechanical ventilation among patients in respiratory care centers. J Nurs Res. 2015;23:65–74. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parsons EC, Kross EK, Caldwell ES, Kapur VK, McCurry SM, Vitiello MV, Hough CL. Post-discharge insomnia symptoms are associated with quality of life impairment among survivors of acute lung injury. Sleep Med. 2012;13:1106–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelly MA, McKinley S. Patients’ recovery after critical illness at early follow-up. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:691–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Granja C, Lopes A, Moreira S, Dias C, Costa-Pereira A, Carneiro A. Patients’ recollections of experiences in the intensive care unit may affect their quality of life. Crit Care. 2005;9:R96–R109. doi: 10.1186/cc3026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parsons EC, Hough CL, Vitiello MV, Zatzick D, Davydow DS. Insomnia is associated with quality of life impairment in medical-surgical intensive care unit survivors. Heart Lung. 2015;44:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee CM, Herridge MS, Gabor JY, Tansey CM, Matte A, Hanly PJ. Chronic sleep disorders in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:314–320. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solverson KJ, Easton PA, Doig CJ. Assessment of sleep quality post-hospital discharge in survivors of critical illness. Respir Med. 2016;114:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Combes A, Costa MA, Trouillet JL, Baudot J, Mokhtari M, Gibert C, Chastre J. Morbidity, mortality, and quality-of-life outcomes of patients requiring >or=14 days of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1373–1381. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000065188.87029.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cronberg T, Lilja G, Rundgren M, Friberg H, Widner H. Long-term neurological outcome after cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2009;80:1119–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skinner MA, Choudhury MS, Homan SD, Cowan JO, Wilkins GT, Taylor DR. Accuracy of monitoring for sleep-related breathing disorders in the coronary care unit. Chest. 2005;127:66–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schiza SE, Simantirakis E, Bouloukaki I, Mermigkis C, Arfanakis D, Chrysostomakis S, Chlouverakis G, Kallergis EM, Vardas P, Siafakas NM. Sleep patterns in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Sleep Med. 2010;11:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masclans JR, Roca O, Muñoz X, Pallisa E, Torres F, Rello J, Morell F. Quality of life, pulmonary function, and tomographic scan abnormalities after ARDS. Chest. 2011;139:1340–1346. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niskanen M, Ruokonen E, Takala J, Rissanen P, Kari A. Quality of life after prolonged intensive care. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1132–1139. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199906000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schiza SE, Simantirakis E, Bouloukaki I, Mermigkis C, Kallergis EM, Chrysostomakis S, Arfanakis D, Tzanakis N, Vardas P, Siafakas NM. Sleep disordered breathing in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:21–26. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.BaHammam A, Al-Mobeireek A, Al-Nozha M, Al-Tahan A, Binsaeed A. Behaviour and time-course of sleep disordered breathing in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:874–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Devine EB, Hakim Z, Green J. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments measuring sleep dysfunction in adults. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:889–912. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Partinen M, Gislason T. Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire (BNSQ): a quantitated measure of subjective sleep complaints. J Sleep Res. 1995;4:150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15:376–381. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hunt SM, McKenna SP, McEwen J, Williams J, Papp E. The Nottingham Health Profile: subjective health status and medical consultations. Soc Sci Med A. 1981;15:221–229. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(81)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snyder-Halpern R, Verran JA. Instrumentation to describe subjective sleep characteristics in healthy subjects. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10:155–163. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weaver TE, Laizner AM, Evans LK, Maislin G, Chugh DK, Lyon K, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Redline S, Pack AI, et al. An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep. 1997;20:835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morgenthaler TI, Lee-Chiong T, Alessi C, Friedman L, Aurora RN, Boehlecke B, Brown T, Chesson AL, Kapur V, Maganti R, et al. Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2007;30:1445–1459. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mallampalli MP, Carter CL. Exploring sex and gender differences in sleep health: a Society for Women’s Health Research Report. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:553–562. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bihari S, Doug McEvoy R, Matheson E, Kim S, Woodman RJ, Bersten AD. Factors affecting sleep quality of patients in intensive care unit. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:301–307. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Corsi-Cabrera M, Sanchez AI, del-Rio-Portilla Y, Villanueva Y, Perez-Garci E. Effect of 38 h of total sleep deprivation on the waking EEG in women: sex differences. Int J Psychophysiol. 2003;50:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(03)00168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liao WC, Huang CY, Huang TY, Hwang SL. A systematic review of sleep patterns and factors that disturb sleep after heart surgery. J Nurs Res. 2011;19:275–288. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e318236cf68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang PL, Huang GS, Tsai CS, Lou MF. Sleep quality and emotional correlates in Taiwanese coronary artery bypass graft patients 1 week and 1 month after hospital discharge: a repeated descriptive correlational study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Redeker NS, Ruggiero J, Hedges C. Patterns and predictors of sleep pattern disturbance after cardiac surgery. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:217–224. doi: 10.1002/nur.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–608. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33:328–336. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Given B, Given CW, McCorkle R, Kozachik S, Cimprich B, Rahbar MH, Wojcik C. Pain and fatigue management: results of a nursing randomized clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:949–956. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.949-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.