Abstract

Aims

To explore the potential influence of the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) on social support in Parkinson disease (PD).

Methods

This was a quasi-experimental mixed methods design. Volunteers with PD (n=27) and care partners (n=6) completed the CDSMP, questionnaires of social support and self-management outcomes, and an interview about social support in relation to CDSMP participation. PD participants (n=19) who did not participate in the CDSMP completed the questionnaires for quantitative comparison purposes.

Results

Regarding the quantitative data, there were no significant effects of CDSMP participation on social support questionnaire scores; however, there were some positive correlations between changes in social support and changes in self-management outcomes from pre- to post-CDSMP participation. Three qualitative themes emerged from the interviews: lack of perceived change in amount and quality of social support, positive impact on existing social networks, and benefit from participating in a supportive PD community.

Conclusions

Although participants did not acknowledge major changes in social support, there were some social support-related benefits of CDSMP participation for PD participants and care partners. These findings provide a starting point for more in-depth studies of social support and self-management in this population.

Keywords: social support, self-management, Parkinson’s disease, caregiving

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic, neurodegenerative disease associated with death of the dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra of the midbrain and a wide variety of motor and non-motor symptoms. Over 60,000 Americans are diagnosed annually with PD (Olanow, Watts, & Koller, 2001). The combined direct and indirect costs of PD in the United States are estimated to be $25 billion per year and involve multiple factors such as treatment, social security payments, and loss of income due to inability to work (Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, 2016). PD has a considerable impact on the daily lives of individuals and their families (Haahr, Kirkevold, Hall, & Ostergaard, 2011; Thordardottir, Nilsson, Iwarsson, & Haak, 2014). People with PD have impaired motor performance due to bradykinesia, tremor, postural instability, and rigidity. People with PD also experience non-motor symptoms such as cognitive impairment, fatigue, and depression(Jankovic, 2008). Both motor and non-motor symptoms negatively impact health-related quality of life (QOL) (Chapuis, Ouchchane, Metz, Gerbaud, & Durif, 2005; Santos-García & de la Fuente-Fernández, 2013). Motor and non-motor symptoms have also been shown to increase caregiver distress (Lau & Au, 2011). Additionally, care partners of individuals with PD are at a high risk of caregiver burden, leading to worsening personal health, diminished social engagement, and increased depressive symptoms (Schrag, Hovris, Morley, Quinn, & Jahanshahi, 2006; Shin, Lee, Youn, Kim, & Cho, 2012), which in turn can negatively affect the individual with PD’s QOL (Schrag et al., 2006).

Social support, or the perceived amount and adequacy of socioemotional and instrumental aid (Thoits, 1982), may mitigate the impact of chronic disease like PD on quality of life. The stress-buffering hypothesis, which postulates that good social support can protect one’s well-being against the negative effects of stress (Cohen & McKay, 1984), describes a psychosocial mechanism through which this may be achieved. Indeed, existing literature suggests good social support is associated with multiple psychological benefits for individuals with PD, including decreased stigma (McComb & Tickle-Degnen, 2006), depression, and anxiety (Saeedian et al., 2014; Simpson, Haines, Lekwuwa, Wardle, & Crawford, 2006) as well as increased assistance in activities of daily living, emotional well-being, communication (McComb & Tickle-Degnen, 2006), life satisfaction (Takahashi, Kamide, Suzuki, & Fukuda, 2016), and positive affect (MacCarthy & Brown, 1989; Simpson et al., 2006). Likewise, good social support from caregivers may ensure effective implementation of PD-specific management strategies (Lyons, 2004), and good support for caregivers may be associated with reduced caregiver burden (Schrag et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2012). Social support may also influence health and well-being through its effects on the activity of the genome as has been revealed by the emerging field of social genomics (e.g., Cole, 2013, 2014); however, to our knowledge, this has not yet been studied in PD.

Despite the known benefits of social support for PD and a variety of health conditions, there is a paucity of research on how to best promote social support in people with PD and their caregivers (Bhimani, 2014; McComb & Tickle-Degnen, 2006; Newsom & Schulz, 1996). In fact, people with PD cite issues related to social support (emotional coping, relationships, and social aspects) as critical to their QOL but commonly missing from their healthcare and educational experience (Kleiner-Fisman, Gryfe, & Naglie, 2013). Self-management interventions, which are designed to equip individuals with skills and knowledge to effectively manage their health condition (Gallant, 2003), may be one way to promote the development and use of social support among people with PD (Christiansen, Baum, Bass, & Haugen, 2015). Indeed, self-management practice occurs within the social environment (Reeves et al., 2014; Vassilev, Rogers, Kennedy, & Koetsenruijter, 2014). As Gallant (2003) suggests, social network members, such as care partners, doctors, or friends can influence self-management behaviors through hands-on help with tasks, facilitating the environment for practice of self-management skills, or offering verbal encouragement or advice for engaging in self-management behaviors. Furthermore, self-management interventions may inspire individuals to seek out the support they need to manage their health condition.

The Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program(CDSMP) is a self-management intervention that combines education and support group elements to address multiple aspects of living with a chronic condition (Lorig, Ritter, et al., 2001; Lorig, Sobel, Ritter, Laurent, & Hobbs, 2001; Lorig et al., 1999). In addition to conveying information relevant to chronic disease self-management, the CDSMP includes interactive components, such as feedback and problem-solving, and encourages the sharing of personal experience and strategies for living – features which may provide its participants with emotional, informational, and belonging support (Cohen et al., 1985). Some CDSMP topics of discussion are directly relevant to social support, such as diet management (instrumental support) and communication with loved ones or healthcare professionals (emotional and informational support). Participants in the CDSMP are also encouraged to establish social relationships during the workshop. For example, a twenty-minute break in the middle of each class fosters participant relationships through time to socialize and converse about individually-selected topics. Thus, we hypothesize that the CDSMP has the potential to promote social support among people with PD because it incorporates activities and content related to social support within its curriculum.

In this study, we used quantitative and qualitative methods to explore the impact of CDSMP participation on social support in people with PD. We used Cohen and colleagues’ characterization to guide our measurement, whereby social support includes four functional components: instrumental, emotional, informational, and belongingness (Cohen & Hoberman, 1983; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Thoits, 1982). Instrumental support is the provision of tangible services or aid. Emotional support involves the provision of trust, empathy, and love. Informational support is the provision of advice, guidance, and appraisal. Belongingness or social connectivity refers to quality and quantity of time spent with others. We sought to understand the following: 1) Does the CDSMP increase perceived social support for individuals with PD and their caregivers? 2) Are potential changes in social support in response to CDSMP participation associated with changes in self-management outcomes? We hypothesized that participation in the CDSMP would produce measurable improvement in PD participants’ perceived social support (i.e., increased social support questionnaire scores) and that qualitative data would support and provide additional context and rationale for these findings. We also predicted an association between CDSMP-driven changes in social support and changes in broader self-management outcomes.

METHODS

Design

This study used a triangulation mixed method design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). Quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently, analyzed separately, and then the results were converged during interpretation. The quantitative portion was a quasi-experiment with pre- and post-test. There were three groups of participants: two groups of CDSMP workshop participants (PD-Workshop and Care Partner-Workshop [CP-Workshop]) and a group of PD participants who did not participate in the workshop (PD-Control). Data were collected via questionnaires 1–2 weeks prior to starting the workshop (Pre) and then again within three weeks of completing the workshop (Post). The qualitative portion involved semi-structured interviews with a subset of PD- and CP-Workshop participants at Post to further explore the potential social support effects of the CDSMP. PD-Control participants completed the questionnaires at the same time points but did not participate in the workshop or semi-structured social support interview. Because interview questions were designed to examine social support in relation to CDSMP participation, PD-control participants were not interviewed. The protocol was approved by the university’s review board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Individuals with PD were recruited from the university’s movement disorders center and the local chapter of the American Parkinson’s Disease Association (APDA). Males or females aged 30 or older with a diagnosis of idiopathic PD classified at Hoehn & Yahr stage I–III (mild-moderate disease severity) (Hoehn & Yahr, 1967)were eligible to participate. Care partners (e.g., spouses, family members, or friends) of PD-Workshop participants were invited to participate in the study. Exclusionary criteria for PD participants and care partners included suspected dementia (determined by physician or a score of <25 on the Mini Mental Status Examination [MMSE](Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975)), brain surgery (e.g. pallidotomy, subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation), history of or current psychotic disorder, or anything that would practically limit study participation (e.g. lack of transportation, non-English speaking). Individuals with PD who met inclusion criteria but could not participate in the workshop due to personal circumstances (e.g., travel distance, scheduling conflicts) were asked to serve as control participants (PD-Control). This method of allocation allowed us to conveniently construct a comparison group with similar characteristics, including being interested in participating in the CDSMP, as the PD-Workshop group.

Workshop participants were recruited on a rolling basis and placed into a CDSMP workshop based on availability, location preference (APDA or university), and class offerings. Eight total workshops were offered during the 22-month study period (June 2013 to October 2015). Class sizes ranged from 4 to 17 participants, in accordance with CDSMP guidelines, and either had mild stroke, PD members, and care partners (five classes) or only PD members and care partners (three classes).

Intervention: Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP)

The CDSMP is a self-management program for individuals with chronic disease and their care partners developed at Stanford University (Lorig, Sobel, et al., 2001; Lorig et al., 1999). Each class series (i.e., workshop) consists of six 2.5 hour classes held weekly in a community setting. Classes were led by two trained facilitators who guided participants through general information and activities that promote management of personal health using a scripted leader’s manual. Each participant received a copy of the companion book, Living a Healthy Life with Chronic Conditions, 4th Edition (Lorig et al., 2012), which provides supplementary information to supplement class material. Participants were required to attend at least four of the six classes to be included in the study.

Quantitative Assessment

Demographic and clinical characteristics (e.g., medications, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Motor Score (Goetz et al., 2007)) were collected, and the MMSE and Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996)were administered to characterize the sample. The primary variables of interest were assessed using standardized self-report questionnaires (described below).

Social support, the primary outcome variable, was assessed by the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) general population scale, a 40-item scale with four 10-item subscales (Appraisal, Tangible, Self-Esteem, and Belonging) (Cohen et al., 1985). Items consist of statements regarding the presence of various aspects of social support that are rated on a four-point scale (3 = definitely true, 2 = probably true, 1= probably false, 0 = definitely false). Items are averaged to produce subscale scores and summed to produce a total score(Crane & Constantino, 2003). Higher scores indicate more perceived social support. The ISEL has high internal consistency reliability (α = 0.77), adequate test-retest reliability (r = 0.70 after 6 weeks; r = 0.87 after 2 weeks), and good content and discriminant validity (Cohen & Hoberman, 1983; Cohen et al., 1985).

Several measures were administered to explore whether potential change in social support from CDSMP participation was associated with change in self-management outcomes. The Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scale (CDSES)evaluated participants’ confidence to engage in healthy, self-management behaviors (Lorig et al., 1996). The Parkinson Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39)assessed PD-specific aspects of health status(Jenkinson, Fitzpatrick, Peto, Harris, & Saunders, 2008). Community Participation Indicators (CPI) assessed frequency and importance of participation in home, community, socioeconomic, and social domains (Involvement in Life Situations scale, CPI Involvement) and the participation values of enfranchisement and empowerment (Control over Participation scale, CPI Control)(Heinemann et al., 2011; Heinemann et al., 2013).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were stored and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the university (Harris et al., 2009) and analyzed using SPSS v.21 for Windows. In the case of missing data on questionnaires, missing values were replaced by the person-mean on that particular subscale when at least 75% of the items of the scale were available for a participant. To investigate the effect of CDSMP participation on social support, mixed ANOVAs compared social support scores across PD group (PD-Workshop, PD-Control) and time point (Pre, Post). Separate models were conducted for the Total ISEL score and each of the ISEL subscales. Pre to post intervention change scores were calculated for the social support and self-management scales. Bivariate correlations (Pearson r) were then used to investigate the relationships between social support and self-management change scores in the PD-Workshop group. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Qualitative Assessment

One to three weeks after the final CDSMP class, all workshop participants were invited to participate in an individual semi-structured interview. Questions were designed to provide an understanding of the participants’ perceptions of the tangible, emotional, informational, and belongingness social support they receive in their daily lives (Cohen & Hoberman, 1983; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Thoits, 1982) and whether they perceived any change in social support and social relationships from participating in the CDSMP (see Appendix). Each interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim by a study team member. A different study team member checked transcription accuracy by listening to the recording while reading its transcription and made changes if necessary. Then the primary researcher and a study team member (K.P. and T.D.) established codes and themes for the data to maintain internal consistency reliability. Initial codes were established independently, then compared and differences resolved to create final codes. After final codes were established, the same steps were used to establish themes. Established thematic analysis guidelines (Braun & Clarke, 2006) using a qualitative descriptive approach (Sandelowski, 2000) guided this process. Qualitative results were then used to corroborate quantitative results to gain a thorough understanding of social support within the context of the CDSMP in PD (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007).

RESULTS

Participants

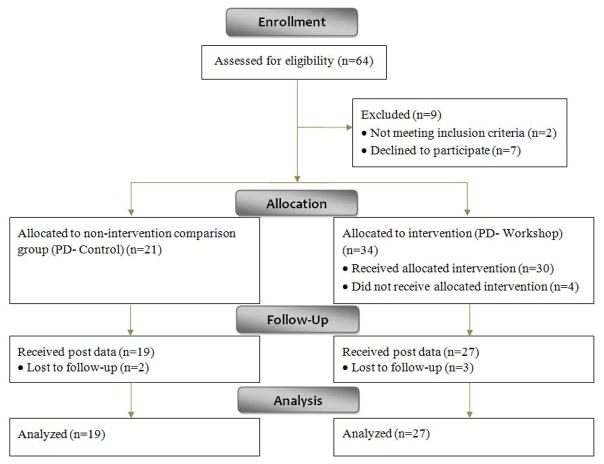

The final sample included 52 participants (27 PD-Workshop, 19 PD-Control, 6 CP-Workshop) (Figure 1). Twenty participants were recruited through the university’s movement disorders center, and thirty participants were recruited through APDA advertisements and outreach. The CP-Workshop participants’ quantitative data were not analyzed due to the small sample size. Demographic and clinical characteristics for all groups are reported in Table 1. The PD-Workshop group had more comorbid conditions (t(39)= 2.71, p = 0.01) and depressive symptoms (t(36) = 2.27, p = 0.03) than the PD-Control group. There were no other differences between the PD-Workshop and PD-Control groups in these characteristics at baseline (p ≥ 0.14).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of PD participants.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 52)

| PD-Workshop | PD-Control | CP-Workshop | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 27 | 19 | 6 |

| Male/female ratio | 16/11 | 14/5 | 2/4 |

| Age, yra | 69.2 (6.7) | 66.2 (6.9) | 69.2 (6.7) |

| Education, yra | 16.3 (2.7) | 17.0 (2.7) | 15.6 (2.2) |

| Work Status | |||

| Working | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Not working | 23 | 16 | 5 |

| Living Status | |||

| Living with spouse or family | 25 | 19 | 5 |

| Living alone | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of comorbid conditionsb* | 5.7 (4.0) | 2.7 (2.5) | 3.8 (1.5) |

| BDI-IIc* | 11.5 (8.1) | 6.4 (5.1) | 4.8 (2.4) |

| MMSEd | 28.7 (1.6) | 29.1 (1.3) | 30.0 (0.0) |

| UPDRSe | 24.6 (9.0) | 20.0 (13.0) | NA |

| Hoehn &Yahr stage f | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | NA |

| 2 | 9 | 15 | NA |

| 2.5 | 3 | 0 | NA |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | NA |

Note. Data are reported as Mean (Standard deviation) or numbers of participants. BDI-II= Beck Depression Inventory II; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination UPDRS = Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Motor score (on medications),

PD-Workshop different from PD-Control, p < 0.05

Variables with missing participants are denoted by superscript letters as follows:

CP-Workshop n = 5

PD-Workshop n = 24, Control n = 17, CP -Workshop n = 4

PD-Workshop n = 21, Control n = 17, CP-Workshop n = 5

CP-Workshop n = 3

PD-Workshop n= 16

PD-Workshop n=17

Quantitative Results

There were no significant group, time, or interaction effects for any of the social support outcomes, Fs ≤ 1.19, ps ≥ 0.28 (Table 2). Correlations between social support and self-management change scores for the PD-Workshop group are in Table 3. ISEL Total and all ISEL subscale change scores correlated with CPI Involvement change scores (r ≥ 0.59, p ≤ 0.03), and ISEL Belonging change scores correlated with CPI Control change scores (r = 0.73, p < 0.01) such that participants who reported improved social support also reported improved participation. ISEL Appraisal change scores correlated with PDQ Summary Index change scores (r = −0.58, p = 0.03) such that participants who reported improved appraisal social support also reported improved health status.

Table 2.

Pre- and Post-Intervention ISEL subscale and total scores for the PD groups.

| PD-Workshop | PD-Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Appraisal Subscale | 20.7 (1.7) | 19.5 (1.8) | 20.2 (1.4) | 19.8 (1.5) |

| Tangible Subscale | 20.7 (1.4) | 21.3 (1.5) | 20.3 (1.3) | 20.6 (1.4) |

| Self-Esteem Subscale | 17.8 (1.2) | 18.8 (1.5) | 16.8 (1.0) | 17.3 (1.2) |

| Belonging Subscale | 19.2 (1.4) | 19.2 (1.4) | 19.2 (1.2) | 20.4 (1.2) |

| ISEL Total | 77.8 (5.3) | 78.4 (5.7) | 76.6 (4.5) | 78.2 (4.9) |

Note. Scores are reported as Mean (Standard deviation).

Table 3.

Correlations of social support and self-management outcome change scores for PD-workshop participants.

| CDSES | PDQ-SI | CPI Involvement | CPI Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appraisal | 0.35 | −0.58* | 0.59* | 0.43 |

| Tangible | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.73* | 0.06 |

| Self-Esteem | 0.35 | −0.48 | 0.65* | 0.37 |

| Belonging | 0.40 | −0.27 | 0.77* | 0.73* |

| Total | 0.34 | −0.49 | 0.88* | 0.51 |

Note. CDSES = Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scale; PDQ-SI = Parkinson Disease Questionnaire-39 Summary Index; CPI = Community Participation Indicators

p < 0.05

Qualitative Results

Twenty participants (14 PD-Workshop, 6 CP-Workshop) agreed to take part in the post-workshop semi-structured interview. Interviews averaged approximately twenty-two minutes in length. Eleven randomly selected interviews from this pool (7 PD-Workshop, 4 CP-Workshop, 4 PD-CP dyads; 55% of total data set) were coded and analyzed for themes by two study team members (K.P. and T.D.), and then the additional nine interviews (7 PD-Workshop, 2 CP-Workshop, 2 PD-CP dyads) were coded and analyzed for themes by the primary researcher (K.P.) only. Thematic analysis revealed three main themes: 1) Lack of perceived change in amount and quality of social support, 2) Positive impacts on existing social networks, and 3) Benefit from participating in a supportive PD community.

Theme 1: Lack of perceived change in amount and quality of social support

Participants reported that the overall frequency, amount, and quality of social support they received had not changed since participating in the CDSMP. Participants were highly satisfied with their current social support and care partner relationships, did not perceive a need for increased social support currently, and did not see the CDSMP as explicitly facilitating major changes in social support. Three subthemes explain these findings.

1a: Social support is viewed as a response to functional dependence

Many PD-workshop participants did not perceive themselves to be in need of social support due to their high current level of functional status.

PDW1: I just don’t need a lot of support right now. Except for emotional, he’s always there for that. I think you need a sicker person.

PDW12: I don’t need that presently. I’m pretty good with all that stuff.

Others reported receiving some form of physical assistance from others that mitigated the impact of physical limitations on participation in daily activities and thus was satisfying to them.

PDW14: [My care partner and I] recognize skills that maybe I can’t do as well as I used to, and instead of being frustrated by something I can’t do, just kind of changing roles in my daily life, someone else doing something for me.

PDW6: At least I know someone’s there when I can’t walk. [Be]cause falling is not fun. So at least when I’m with somebody else I know that I can at least have [someone to] maybe open the door or help me get in the car or help me get around.

However, all PD participants greatly valued maintaining their functional independence and, for example, adopted behaviors to try to prevent the need for assistance.

PDW4: No, as a matter of fact I’ve avoided that. I’m trying to walk, jog, pick up leaves, do everything I can to be active.

Despite contentment with their present functioning, most participants also expressed an understanding that functional status would decline with disease progression and thus would result in an increased need for social support and the skills learned in the CDSMP. Most PD and CP participants were confident they would be able to fulfill these future needs.

PDW7: I think that management that they teach us can do a lot of good for some. Me, I feel like I’ve been managing it pretty well, but I did learn some good things in there [the CDSMP] that will help me in the future.

However, one CP participant expressed social support concerns as her loved one’s disease progresses.

CPW3: I guess I am most concerned and frightened by the progression of the disease. At this point, I can handle it. But I know there will come a time, and I don’t know when, but I will need some emotional support, someone to speak with.

1b. Consistent and effective existing social networks

Participants described consistent networks of close friends and family members that provided instrumental, informational, and emotional support. These relationships were cooperative, reciprocal, and involved a sense of connection.

PDW5: We are our own inner support group. I support my granddaughter and daughter in their illness and they support me with mine. Their support is an inner circle for us. We keep each other’s spirits up and we help each other the best we can.

PDW11: I have a good friend whose husband had Parkinson’s and he passed away a couple years ago. She is very much my soundboard and we meet for coffee or lunch and we can talk about anything.

Spouses were generally the main source of all forms of social support for PD and CP participants, and some participants described role reversal within the care dyad. This process was often described as fluid and consistent with relationship quality before PD. Care partners were also often identified as the primary investigators of informational support resources.

CPW1: You know, the more she can’t do, the more I have to do, it’s as simple as that. You don’t even think about it.

CPW8: I am finding more and more people who do not ask, call, or do. I say there is so much out there, you just have to ask for it.

Due to high care partner involvement, many participants also indicated concern for caregiver burden and the importance of respite care.

PDW12: My caregiver would be my spouse and she has always taken good care of me. She is a giver if you want to define her as a person. When I say I am too much of a burden, she says ‘You need to let me do more for you.’ I don’t want to deprive her of anything of her own activities or anything like that, you know.

CPW8: I try to get away at least twice a month. I just came back from a two night stay from my sister’s. But I try to get away for a whole day by myself. That is how I cope.

1c. CDSMP lacks features to facilitate the development of social support

Although participants generally expressed enjoying the CDSMP, many indicated a need for information about dealing specifically with social issues related to PD, such as how to respond to self and others’ reactions to PD and care partners’ roles.

PDW14: People will find out I have Parkinson’s disease and the way they react to me will determine pretty quickly whether I continue to talk to them about it or whether they are cut off. I don’t think people mean to be mean or hurtful. How do you deal with that internally, how do you deal with that externally, would be a good thing to know.

Participants formed acquaintances with other CDSMP participants but described these relationships as surface-like and said they could not be counted on for support. Some felt that the program could have more explicitly promoted relationship development among class members.

PDW3: It was just those meetings. I don’t know that anything fits that category [friendship].

CPW6: We’re pretty full with family and friends that that’s not something we’re seeking.

PDW1: I don’t know if we would’ve done it [maintained social connections with group members] on our own, so maybe if that was suggested [at a CDSMP class], people would have taken it up as an idea.

Theme 2: Positive impact on communication within existing social networks

Many participants mentioned enhanced understanding and cooperation within their existing social networks. Most notably, the CDSMP facilitated communication with spouses and peers about disease management.

PDW14: I probably talk to her [wife] more about my disease, more about the symptoms, more what we could expect or not expect, but my wife has always been real supportive from the very beginning for me so it [relationship with wife] changed in as much as I am a little bit more open to talking to her about it.

CPW9: I think just the fact of myself as a caregiver with my husband doing this together is also a helpful thing, just increases the support for both of us. I think that actually the group, just being in that group increases the support. Yeah we are just in the boat together and the sun is shining more because we are in the boat together.

Within the CDSMP, the communication skills and medication management topics, practicing the skills of action planning, decision making, and problem-solving, and the general encouragement of communication among class participants were most frequently cited as having a positive impact on existing social networks.

PDW6: The communication skills, kind of a feel, felt, found thing. If you’re in a confrontation with someone then they know how you feel and if I felt the same way however I found it, if we work together we can solve this problem. Making decisions, writing a list down of what to do and not to do, I’d kind of always known that and done that at work. Sometimes you forget so you need a refresher.

CPW8: I’m hoping it [the CDSMP] has helped us to be a little more communicative. I think that maybe he [care receiver] saw how other people were willing to open up and talk.

Theme 3: Benefit from participating in a supportive PD community

Most participants felt more supported from the PD community at large as a result of CDSMP participation. They valued membership in this community as illustrated by the following two subthemes.

3a. Increased disease understanding from peer experiences

Participants expressed value in listening to and learning from other participants’ experiences with PD. Peers were sources of informational and belongingness support, as they learned from and related to each other’s disease management successes and challenges.

CPW1: You get with these people and you sit down and everyone is frank, you know, that’s the one thing I really like about it. You don’t find people pullin’ their punches or anything, you know, they tell you what the problems are and how they’ve dealt with them, or in some cases, how they haven’t dealt with them.

PDW3: I guess it was just nice to know there are other people with similar problems just at various stages of the same problems.

Interactions among participants across disease stages appeared to increase individuals’ self-efficacy for confronting current and future challenges related to PD management. Rather than focus on fear of disease progression, participants seemed to feel empowered to manage uncertain and unpredictable changes.

PDW13: There are other people that are, have the same problems and same illness and everything and are at different points in that process. Some you kinda look at and don’t even think they look like they have any problems. But then others are obviously very, you know, almost handicapped by it but still coming and staying active and everything so I think it’s been an encouragement.

PDW14: I think that just by taking the class and being with the other people that have Parkinson’s disease…probably prompted me [to share PD diagnosis with employer].

The importance of shared peer experience was highlighted by the PD participants who participated in the mixed workshops with stroke participants. These participants expressed a desire for more people with PD in their workshop.

PDW11: I think if you had more Parkinson’s patients, because you can more relate and advise. It’s hard for me to envision how to help somebody who’s had a stroke and how to say ‘you should – I suggest you do this kind of exercise.’…With Parkinson’s, I know what can help. And I just feel like that’s a whole different situation than Parkinson’s. And it would be more helpful talking to Parkinson’s patients one-on-one.

3b. Value in access to resources

Participants also felt a connection to other individuals with PD and their care partners through resources that were specific to PD. Most participants mentioned feeling connected to the PD community and improving their self-management and disease understanding through the general informational resources and activities offered from the local APDA.

PDW3: Just going out to the [APDA] and seeing the wide spectrum of literature that’s there and the CD’s…So that, that was good in that uh, it was good to see all that literature on the problems you have. And about how to manage ‘em, etcetera.

CPW8: If I have a question that I cannot get an answer from my support group, family, and friends then I will go to the APDA and ask.

PDW1: I exercised before I got this. But I-I’ve become a real believer in the value of exercise. For delaying the degradation of this disease, so, and I got a lot of that from those programs from here [APDA] and other things I’ve read.

Additionally, some individuals with PD may act as a resource for their peers and make efforts to give back to the PD community.

PDW4: I almost considered it almost like my duty to give something back… And it was just a means of trying to help whomever as I said before and then ultimately it’ll have some help for me down the road, maybe ten years from now.

Discussion

Our purpose was to explore the potential influence of a self-management intervention, the CDSMP, on social support among individuals with PD and their care partners. We quantitatively examined change in social support across PD participants who did or did not participate in the CDSMP and correlated changes in social support with changes in self-management outcomes after CDSMP participation. To supplement our quantitative data, PD participants and their care partners who participated in the CDSMP were interviewed about their social support and any perceived changes as a result of class participation. Contrary to our original hypothesis, CDSMP participation was not associated with general improvements in social support. However, qualitative and quantitative results reveal some social support-related effects that may be associated with improved self-management outcomes.

Quantitative analyses showed no overall change in social support in response to CDSMP participation. These results contrast with other studies in which self-management interventions promoted social support for individuals with chronic disease and their care partners (Baig et al., 2015; Won, Fitts, Olsen, & Phelan, 2008). Although there were no treatment effects at the group level, correlational analyses revealed individual-level improvements in social support which were associated with improved participation and health status. This finding reflects the identified positive relationship between social support and self-management and suggests that some people with PD can experience this benefit from the CDSMP (Gallant, 2003).

Our qualitative findings provide some insight into the general perceived lack of change in social support in the current sample (Theme 1). Many participants viewed social support utilization as an indicator of functional decline and described actively avoiding the need for social support by adopting behaviors to maintain their independence. In addition, many participants did not perceive a need for improved social support because they were satisfied with their existing support. This may have resulted in a lack of motivation to make new social connections, which can be explained by social network continuity, or maintaining relationships due to a desire to continue with the familiar in old age (Atchley, 1999). Participants acknowledged the fine line between support and burden for PD care partners, but their descriptions implied successful management of that balance to-date.

It also appears that the structure and content of the CDSMP were inadequate for promoting the development of new social support relationships in this sample. Participants did not feel that the workshop facilitated true relationship building and expressed the desire for explicit encouragement and activities to do so. They also suggested the inclusion of PD-specific content related to social functioning in particular and disease management in general. The CDSMP was designed on the premise that individuals with a variety of chronic diseases share many symptoms and can benefit from similar self-management strategies (Lorig et al., 1999). While this may be true, our interviews indicate that the particular complexities and challenges of PD may warrant special attention in the context of self-management, as has been discussed previously (Lyons, 2004). This interpretation is further supported by the value participants derived from sharing their experiences about PD and accessing PD-specific resources during the course of the workshop. Other PD-specific education and self-management programs have been shown to improve aspects of social functioning in people with PD and/or their care partners (A’Campo, Wekking, Spliethoff-Kamminga, Le Cessie, & Roos, 2010; Tickle-Degnen, Ellis, Saint-Hilaire, Thomas, & Wagenaar, 2010), and it is worth examining whether these programs also promote social support more than a generic program like the CDSMP. Furthermore, since the development of the CDSMP, other groups have developed programs that incorporate self-management and physical exercise (e.g., De Hollander & Barnett, 2016), which may be particularly beneficial for this population as exercise is now well-known to be critical to maintenance of function and well-being (Crizzle & Newhouse, 2006; da Silva et al., 2016).

Although not explicitly labeled by interviewees or detected by the ISEL, qualitative analysis did reveal social support-related benefits from the vicarious experiences (social modeling) and social persuasion that occur within the CDSMP (Bandura, 1977; Lorig & Holman, 2003). It provided the opportunity to speak openly about PD, learn and understand the value of communication skills, and participate in collaborative problem-solving, decision making, and action planning. These experiences positively influenced participants’ interactions with their friends and families outside of class, thus strengthening their existing social support networks. The sharing of PD-related life experiences, advice, and resources that occurred during the CDSMP classes provided informational support and cultivated a sense of belonging among participants, at least while they were in the workshop. Many participants also expressed increased self-efficacy in accessing resources and addressing disease-related challenges; however, this was not reflected by our quantitative findings (i.e., the CDSES), and it is unclear whether it was caused by the CDSMP itself, the fact that it was held at the APDA resource room, or participants’ involvement in other APDA programs. These benefits may represent increased social capital rather that social support (Christiansen et al., 2015; Putnam, 1995). Regardless, supportive communities and social networks are positively associated with self-management behaviors and outcomes, and our results suggest that the CDSMP can facilitate this process to some extent(Li, 2013; Reeves et al., 2014; Vassilev et al., 2014).

Several aspects of our study design may have limited our ability to draw generalizable conclusions from our data, including the relatively small and uneven group sizes, lack of randomization, and convenience sampling. Additionally, our sample may have been relatively high in social support at baseline, as all were living with a spouse or family member and were recruited from the APDA or a specialized care center, which suggests they were already accessing supportive resources. Further, they had transportation and time to attend the workshop, which are potential indicators of relatively high socioeconomic status. In terms of outcome measurement, the ISEL, which has not been validated for PD or neurodegenerative populations, may not have been sensitive to the specific social support issues of people with PD or social support changes that occurred from CDSMP participation. This possibility is reflected by our qualitative findings, which did reveal subtle social support-related benefits of CDSMP participation. However, we also admit that the interviews were limited in their ability to capture the full breadth and depth of potentially relevant data, as they were relatively short, involved some close-ended questions and were only conducted at one time point. Longer term follow-up may also be needed as social support may take some time to develop after workshop participation. Finally, the creation of the qualitative themes could have been influenced by the researchers’ perspectives and the order in which the interviews were coded and analyzed. Initial codes and themes were developed from seven interviews before the remaining interviews were coded and the final themes developed.

Social support is an important contributor to QOL and psychological well-being among individuals with PD (MacCarthy & Brown, 1989; Simpson et al., 2006) and to self-management in other chronic disease populations (Gallant, 2003; Vassilev et al., 2014). Therefore, interventions that increase social support for people with PD and their care partners may enhance self-management, participation, and QOL in this population (Nilsson, Iwarsson, Thordardottir, & Haak, 2015; Tickle-Degnen et al., 2014). Although participation in the CDSMP did not produce general improvements in social support in the current exploratory study, our analyses revealed some specific and individualized social support-related benefits to PD participants and their care partners. These findings have laid the groundwork for future studies that will involve longer term follow-up, different outcome measures, and more in-depth qualitative data collection to better elucidate the effect of CDSMP participation on social functioning and social support in PD. At this juncture, our results suggest that structural modifications and the addition of PD-specific information may increase the potential for the CDSMP to foster social support among people with PD and their care partners.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH (K23HD071059), the Program in Occupational Therapy at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, the Greater St. Louis Chapter of the American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA), and the APDA Center for Advanced PD Research at Washington University in St. Louis.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- A’Campo LE, Wekking EM, Spliethoff-Kamminga NG, Le Cessie S, Roos RA. The benefits of a standardized patient education program for patients with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(2):89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley RC. Continuity and adaptation in aging. Creating positive experiences. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baig AA, Benitez A, Locklin CA, Gao Y, Lee SM, Quinn MT … Little Village Community Advisory, B. Picture Good Health: A Church-Based Self-Management Intervention Among Latino Adults with Diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1481–1490. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3339-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bhimani R. Understanding the Burden on Caregivers of People with Parkinson’s: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Rehabil Res Pract. 2014;2014:718527. doi: 10.1155/2014/718527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chapuis S, Ouchchane L, Metz O, Gerbaud L, Durif F. Impact of the motor complications of Parkinson’s disease on the quality of life. Movement Disorders. 2005;20(2):224–230. doi: 10.1002/mds.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen CH, Baum CM, Bass JD, Haugen K. Environmental Factors: Social Determinants of Health, Social Capital, and Social Support. In: Christiansen CH, Baum CM, Bass JD, editors. Occupational Therapy: Performance, Participation, and Well-Being. 4. Thorofare: SLACK Incorporated; 2015. pp. 359–386. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Hoberman HM. Positive Events and Social Supports as Buffers of Life Change Stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1983;13(2):99–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1983.tb02325.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, McKay G. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. Handbook of psychology and health. 1984;4:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H, Sarason IG, Sarason BR. Social support: Theory, research, and application. The Hague, Holand: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. Measuring the functional components of social support. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. Social Regulation of Human Gene Expression: Mechanisms and Implications for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:84–92. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2012.301183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW. Human Social Genomics. Plos Genetics. 2014;10(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004601. ARTN e1004601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PA, Constantino RE. Use of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) to guide intervention development with women experiencing abuse. Issues in mental health nursing. 2003;24(5):523–541. doi: 10.1080/01612840305286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2007. Choosing a Mixed Methods Design; pp. 58–88. [Google Scholar]

- Crizzle AM, Newhouse IJ. Is physical exercise beneficial for persons with Parkinson’s disease? Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16(5):422–425. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000244612.55550.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva FC, Iop RD, dos Santos PD, de Melo LMAB, Gutierres PJB, da Silva R. Effects of Physical-Exercise-Based Rehabilitation Programs on the Quality of Life of Patients With Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2016;24(3):484–496. doi: 10.1123/japa.2015-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hollander C, Barnett F. The Efficacy of an Eight-Week Exercise and Self-Management Education Program for People with Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2016;24:S75–S75. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatry Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: A review and directions for research. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(2):170–195. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz CG, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, Poewe W, Sampaio C, Stebbins GT, … LaPelle N. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Process, format, and clinimetric testing plan. Mov Disord. 2007;22(1):41–47. doi: 10.1002/mds.21198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haahr A, Kirkevold M, Hall EO, Ostergaard K. Living with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a constant struggle with unpredictability. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(2):408–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann AW, Lai JS, Magasi S, Hammel J, Corrigan JD, Bogner JA, Whiteneck GG. Measuring Participation Enfranchisement. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2011;92(4):564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.07.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann AW, Magasi S, Bode RK, Hammel J, Whiteneck GG, Bogner J, Corrigan JD. Measuring Enfranchisement: Importance of and Control Over Participation by People With Disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013;94(11):2157–2165. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17(5):427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic J. Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(4):368–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Harris R, Saunders P. User Manual for the PDQ-39, PDQ-8 and PDQ Index. 2. Oxford: Health Services Research Unit; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner-Fisman G, Gryfe P, Naglie G. A Patient-Based Needs Assessment for Living Well with Parkinson Disease: Implementation via Nominal Group Technique. Parkinsons Disease. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/974964. Unsp 974964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau KM, Au A. Correlates of Informal Caregiver Distress in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Clinical Gerontologist. 2011;34(2):117–131. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2011.539521. Pii 933885689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Improving chronic disease self-management through social networks. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(5):285–287. doi: 10.1089/pop.2012.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Holman H, Sobel DS, Laurent D, Gonzalez V, Minor M. Living a healthy life with chronic conditions: self-management of heart disease, arthritis, diabetes, asthma, bronchitis, emphysema & other physical and mental health conditions. 4. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing Company; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW, Jr, Bandura A, … Holman HR. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW, Jr, Bandura A, Ritter P, … Holman HR. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Stewart A, Ritter P, Gonzalez VM, Laurent D, Lynch J. Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. SAGE Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KD. Self-management of Parkinson’s disease: guidelines for program development and evaluation. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2004;21(3):17–31. [Google Scholar]

- MacCarthy B, Brown R. Psychosocial factors in Parkinson’s disease. Br J Clin Psychol. 1989;28(Pt 1):41–52. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1989.tb00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComb MN, Tickle-Degnen L. Developing the Construct of Social Support in Parkinson’s Disease. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2006;24(1):45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Schulz R. Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11(1):34–44. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson MH, Iwarsson S, Thordardottir B, Haak M. Barriers and Facilitators for Participation in People with Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Parkinsons Disease. 2015;5(4):983–992. doi: 10.3233/Jpd-150631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson’s Disease Foundation. Statistics on Parkinson’s. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.pdf.org/en/parkinson_statistics.

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy. 1995;6(1):65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves D, Blickem C, Vassilev I, Brooks H, Kennedy A, Richardson G, Rogers A. The contribution of social networks to the health and self-management of patients with long-term conditions: a longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeedian RG, Nagyova I, Krokavcova M, Skorvanek M, Rosenberger J, Gdovinova Z, … van Dijk JP. The role of social support in anxiety and depression among Parkinson’s disease patients. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2014;36(24):2044–2049. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.886727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::Aid-Nur9>3.0.Co;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-García D, de la Fuente-Fernández R. Impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related and perceived quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2013;332(1):136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag A, Hovris A, Morley D, Quinn N, Jahanshahi M. Caregiver-burden in parkinson’s disease is closely associated with psychiatric symptoms, falls, and disability. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2006;12(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H, Lee JY, Youn J, Kim JS, Cho JW. Factors contributing to spousal and offspring caregiver burden in Parkinson’s disease. European neurolog. 2012;67(5):292–296. doi: 10.1159/000335577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J, Haines K, Lekwuwa G, Wardle J, Crawford T. Social support and psychological outcome in people with Parkinson’s disease: Evidence for a specific pattern of associations. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45(Pt 4):585–590. doi: 10.1348/014466506X96490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Kamide N, Suzuki M, Fukuda M. Quality of life in people with Parkinson’s disease: the relevance of social relationships and communication. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(2):541–546. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Conceptual, Methodological, and Theoretical Problems in Studying Social Support as a Buffer against Life Stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1982;23(2):145–159. doi: 10.2307/2136511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordardottir B, Nilsson MH, Iwarsson S, Haak M. “You plan, but you never know”--participation among people with different levels of severity of Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(26):2216–2224. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.898807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickle-Degnen L, Ellis T, Saint-Hilaire MH, Thomas CA, Wagenaar RC. Self-management rehabilitation and health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2010;25(2):194–204. doi: 10.1002/mds.22940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickle-Degnen L, Saint-Hilaire M, Thomas CA, Habermann B, Martinez LS, Terrin N, … Naumova EN. Emergence and evolution of social self-management of Parkinson’s disease: study protocol for a 3-year prospective cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev I, Rogers A, Kennedy A, Koetsenruijter J. The influence of social networks on self-management support: a metasynthesis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:719. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won CW, Fitts SS, Olsen P, Phelan EA. Community-based “powerful tools” intervention enhances health of caregivers. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2008;46(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.