Abstract

Objective:

To quantify the socioeconomic burden of frontotemporal degeneration (FTD) compared to previously published data for Alzheimer disease (AD).

Methods:

A 250-item internet survey was administered to primary caregivers of patients with behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), primary progressive aphasia, FTD with motor neuron disease, corticobasal syndrome, or progressive supranuclear palsy. The survey included validated scales for disease staging, behavior, activities of daily living, caregiver burden, and health economics, as well as investigator-designed questions to capture patient and caregiver experience with FTD.

Results:

The entire survey was completed by 674 of 956 respondents (70.5%). Direct costs (2016 US dollars) equaled $47,916 and indirect costs $71,737, for a total annual per-patient cost of $119,654, nearly 2 times higher than reported costs for AD. Patients ≥65 years of age, with later stages of disease, and with bvFTD correlated with higher direct costs, while patients <65 years of age and men were associated with higher indirect costs. An FTD diagnosis produced a mean decrease in household income from $75,000 to $99,000 12 months before diagnosis to $50,000 to $59,999 12 months after diagnosis, resulting from lost days of work and early departure from the workforce.

Conclusions:

The economic burden of FTD is substantial. Counting productivity-related costs, per-patient costs for FTD appear to be greater than per-patient costs reported for AD. There is a need for biomarkers for accurate and timely diagnosis, effective treatments, and services to reduce this socioeconomic burden.

Frontotemporal degeneration (FTD), the most common dementia in individuals <60 years of age, affects ≈60,000 individuals in the United States.1–4 FTD presents as a diverse group of degenerative disorders with prominent features of language, personality, behavior, cognition, and motor dysfunction made up of 4 predominant clinical phenotypes: behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), primary progressive aphasia, FTD with motor neuron disease, and Parkinson-plus movement disorders due to progressive supranuclear palsy or corticobasal syndrome.1,3 Although presentations differ, all forms of FTD cause progressive loss of function and independence over 2 to 20 years.1–6 The prevalence of FTD is 15 to 22 per 100,000 adults. Compared to Alzheimer disease (AD),7,8 FTD affects younger patients and progresses more rapidly, and patients' symptoms are more variable. Many patients are in their prime earning years, have dependent children, and have difficulty accessing services developed primarily for older adults with dementia. To quantify the socioeconomic burden of FTD, we conducted a web-based survey to characterize the patient and caregiver experience with FTD-related resource use, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and per-patient annual costs.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The Florida Atlantic University Institutional Review Board approved the study as exempt.

Survey design.

Participants (n = 956) were recruited via announcements on the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration website, newsletter, social media, and e-mail blasts. We designed a 250-question internet survey using Qualtrics Survey Software (Provo, UT) to characterize the socioeconomic burden of FTD from the primary caregivers' perspective. No identifiable personal information was collected. Validated scales for clinical characterization and resource use were used whenever available and are described below. We used investigator-generated questions to describe the personal burden of FTD when no validated scale existed. We used these data to estimate the economic burden of FTD. The survey was beta-tested and revised for clarity and readability before its release to the FTD community. The survey took ≈2 hours to complete.

Clinical characterization.

Informant-based questionnaires characterized the patient's symptoms and severity. The 10-question Quick Dementia Rating Scale9 staged dementia severity (range 0–30, higher scores reflect greater impairment). The 12-question Neuropsychiatric Inventory10 assessed behavioral aspects of disease (range 0–36, higher scores indicate more behavioral symptoms). The 10-question Functional Activities Questionnaire11 examined instrumental activities of daily living (range 0–30, higher scores mean greater functional dependence). The 12-question Zarit Burden Inventory12 assessed caregivers' burden (range 0–36, higher scores mean greater burden). In addition, respondents assessed patient disease stage severity at the time of the survey on the basis of their opinion and direct observation of the patient13,14 as mild, moderate, severe, or terminal (capturing the last 6 months of life).

Health utility and resource use.

We measured patients' quality of life and health utility using the Health Utilities Index–3 (HUI3).15,16 The HUI3 measures health-state utility and provides a summary score for HRQoL across 8 attributes (vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, pain), with each attribute having 5 or 6 levels of ability/disability for a total 972,000 unique health states. The HUI3 provides utility scores ranging from 1 (reflecting perfect health) to 0 (dead) with negative scores possible (minimum score −0.371) and reflecting health states deemed “worse than being dead.”15 We estimated quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), representing quality-adjusted life expectancy, by multiplying health utility by survival time.17 As is the case with health utility, negative QALYs are possible, reflecting survival in health states being worse than death. Negative HUI3 and QALY scores reflect the respondents' belief that there is no perceived positive quality of life for the patient in this state.

The Resource Utilization Inventory (RUI)18,19 measures patient and caregiver dementia-associated costs, the use of formal and informal care, and the loss of paid employment. There are 4 domains: direct medical care, direct nonmedical care, informal care, and caregiver time. Actual costs are determined via Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, Evaluation and Management codes, and Diagnosis Related Groups. We calculated the mean response for each resource use question. We omitted missing values unless the patient resided in dependent care and the resource is used primarily by community-dwelling patients (i.e., home health aides). In that case, we assumed that the respondent did not use that resource in the event of nonresponse. There were no differences between completers and noncompleters for any variable after correction for multiple comparisons.

We assigned dollar values to hospital admissions on the basis of the admission-weighted average of Medicare reimbursements for Diagnosis Related Groups 56 and 57 (degenerative nervous system disorders, with and without a major complication or comorbidity). We used the Medicare reimbursement for an Evaluation and Management visit for an established patient (CPT 99214) to assign a dollar value to office visits and CPT 97110 to assign a dollar value to physical therapy visits. We used estimates from Genworth20 to assign dollar values to assisted living care, nursing home care, and respite care. We adjusted nursing home and assisted living costs downward by 8% to account for the costs of food and shelter.21 We obtained costs for medical equipment from the Medicare fee schedule.22

We estimated costs for paid home care using Genworth20 and costs for unpaid care using wage estimates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.23,24 Table e-1 at Neurology.org provides details for cost estimates. We estimated lost productivity by asking whether patients and caregivers were out of the labor force as a result of FTD. We valued lost productivity for patients using average annual earnings25 multiplied by 1.25 to account for fringe benefits. We valued lost productivity for caregivers by subtracting the annual cost of hiring a home health aide from average earnings.

We calculated the annual per patient costs considering direct costs (patient medical care, patient residential care, respite care, patient medical equipment and supplies, and paid home care with formal caregivers) and indirect costs (unpaid home care for family and friends, patient lost wages, and caregiver lost wages). Average costs were determined by multiplying the average use by the price per item. For example, patients experienced an average of 0.6 hospitalizations per year. If the typical reimbursement per admission is $36,044, then the average cost in the sample is $21,626 (0.6 × $36,044). We calculated direct and indirect costs by summing across average costs for individual RUI items. Some respondents answered only a subset of the cost-related questions. We calculated average costs on the basis of the subsample of respondents who answered the relevant questions for each cost item.

Statistical analyses.

Analyses were conducted with SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics characterized the caregiver respondents and the patients. We compared groups using analysis of variance for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. We compared median incomes using Kruskal-Wallis tests. We used a generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and log link to estimate the relationship between patient-level costs and patient characteristics and summed costs by item at the individual level. We restricted the sample to respondents who had nonmissing responses for at least 15 of the 18 RUI items (n = 595 respondents) and recoded any remaining missing values to zero. We selected the cutoff of 15 to balance the benefit of including as many respondents in the analysis as possible against the disadvantage of including respondents with incomplete cost data. Respondents who answered 15 items were similar in terms of sex, age, disease type, and disease duration to respondents who answered <15.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics.

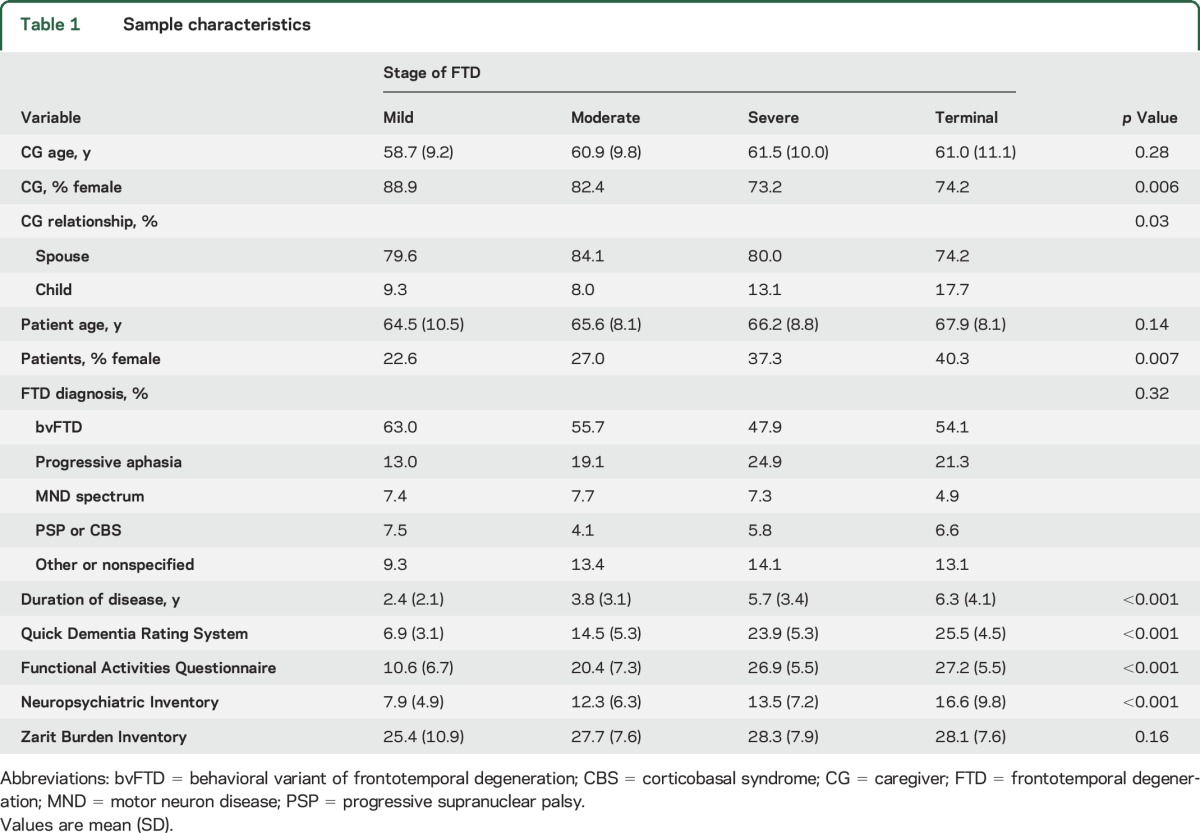

Nine hundred fifty-six individuals started the survey, and 674 (70.5%) completed it. There were no significant demographic differences between completers and noncompleters. The patients were divided into 4 groups (table 1) based on the caregiver's assessment: mild, moderate, severe, or terminal. The majority of caregiver respondents were female spouses, while the majority of patients were men. The diagnostic groups were 52.9% bvFTD, 21.1% primary progressive aphasia, 7.3% FTD with motor neuron disease, and 5.4% progressive supranuclear palsy or corticobasal syndrome, while 13.3% were undefined FTD (i.e., the respondent did not know the subtype). As demonstrated in table 1, the caregiver global ratings matched well with duration of disease and standardized rating scales of global staging (Quick Dementia Rating Scale),9 behavior (Neuropsychiatric Inventory),10 and function (Functional Activities Questionnaire).11 Caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Inventory)12 was not different across stages of disease.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

Changes in household income and lost days of work.

At the time of survey, 45% of caregivers still worked, while 37% were no longer employed after the patient's FTD diagnosis. Seventy-four percent of caregivers worked full-time. Only 3.3% of patients were still working. Caregivers reported lost days of work due to patient health issues (25.6%) or caregiver health issues (21.6%). Caregivers and patients who were still working full-time reported a median loss of 7.0 days over the previous 4 weeks due to FTD-related matters.

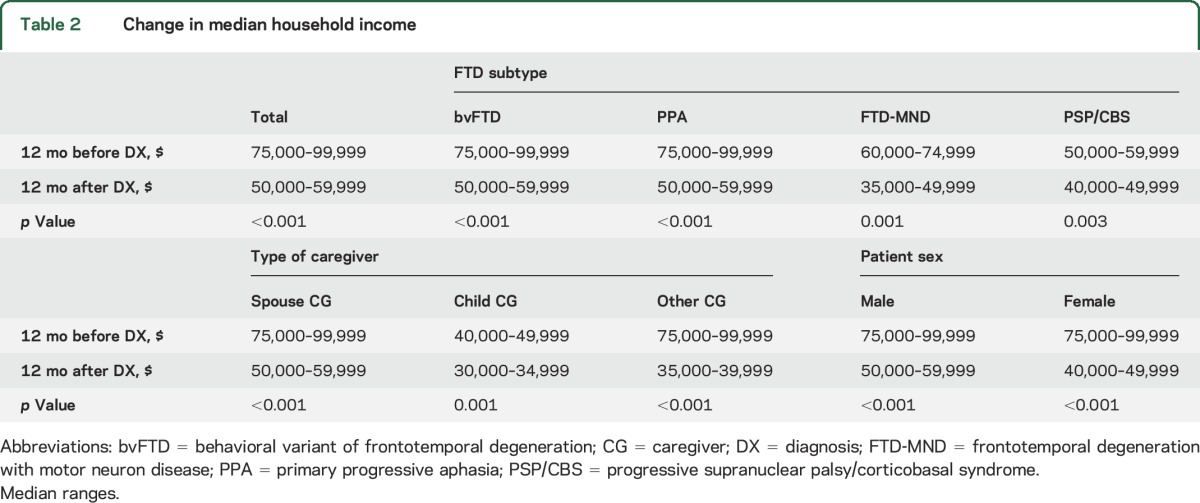

Respondents provided the total household income for the patient and family 12 months before and 12 months after the FTD diagnosis (table 2). The overall household income before diagnosis ranged from $75,000 to $99,000 but declined after diagnosis to $50,000 to $59,999 (p < 0.001). There were no differences in the extent of loss of household income by FTD subtype, caregiver type, or patient sex (table 2).

Table 2.

Change in median household income

Patient and caregiver health costs associated with FTD.

We found that 67% of caregivers of patients with FTD reported a notable decline in their health and that 53% reported increased personal health care costs calculated from the RUI. On average, caregivers had 7 clinician visits and slightly less than 1 inpatient admission per year. On average, patients had 6 overnight respite stays, 16 daytime respite stays, 35 clinician visits, and 2 hospital or emergency room visits. In addition, 31.6% of respondents needed to hire a paid caregiver several times per week.

Estimates of annual per patient costs.

Total direct costs (i.e., the value of goods and services for which there are explicit monetary payments) were $47,916. Total indirect costs (the value of the changes in the provision of goods and services that are attributable to FTD but for which there are no explicit monetary payments) were $71,737. The sum of estimated direct and indirect costs is $119,654.

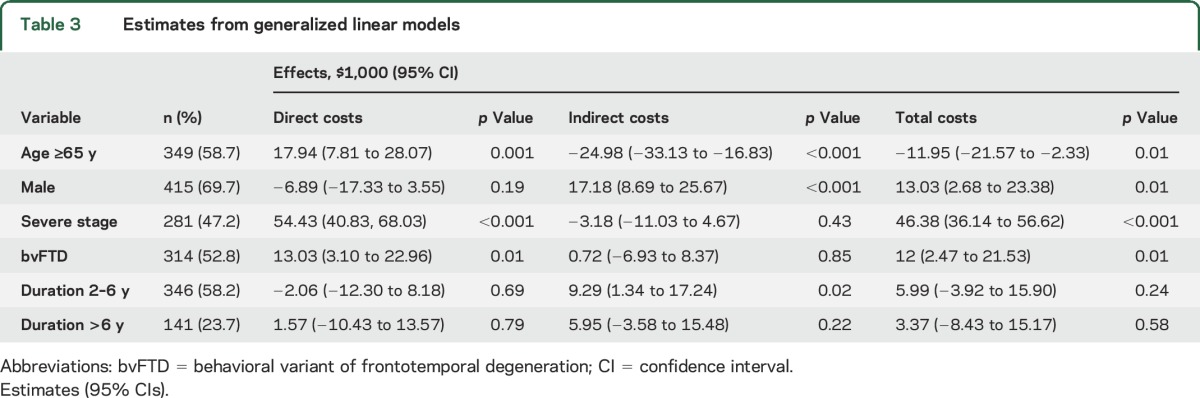

Table 3 reports the relationship between patient characteristics and costs. The sample used in the regression analysis had a higher proportion of men (69% vs 61%) but was otherwise similar in terms of age, stage, underlying diagnosis, and disease duration. Patients ≥65 years of age incurred higher direct costs ($17,900) but lower indirect costs ($25,000). Men had higher indirect costs because they were more likely to use unpaid care and to have stopped working because of the disease. Women had higher direct costs, mainly because they were more likely to live in nursing homes or assisted living facilities. Patients with severe or terminal stages of disease incurred higher direct costs ($54,000). Across the FTD subtypes, bvFTD had higher direct costs ($13,030) than other subtypes.

Table 3.

Estimates from generalized linear models

Other costs associated with FTD.

Caregivers also reported patient-related crises during the prior year: 19% required an emergency department visit, 11% required emergency medical services, 8% required urgent psychiatric care, 6% required police intervention, and 6% required contacting a lawyer. Poor financial decisions by patients with FTD were reported by 58% of respondents. Legal costs were reported by 9.6% of respondents, attributed largely to court appearances and attorney fees. The leading reasons for court appearances included legal guardianship (9.0%), bankruptcy (4.4%), loss of home (3.9%), loss of business (3.8%), criminal cases (3.2%), and civil lawsuits (2.7%). The leading reasons for attorney fees included initiating a power of attorney (25.9%), revising wills (22.9%), guardianships (7.6%), and court appearances (5.8%).

Changes in HRQoL.

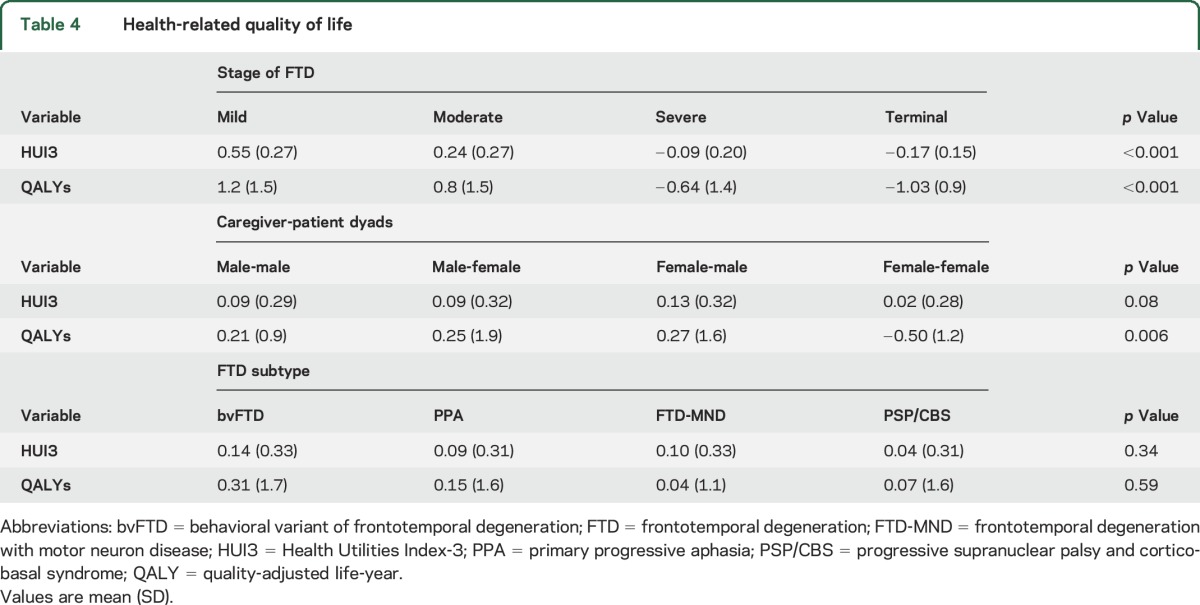

Table 4 reports HUI315,16 scores and QALYs17 by severity of disease, FTD subtype, and caregiver-patient dyadic relationships. HUI3 scores and QALYs were lower for patients in the severe and terminal stages, with scores indicating that patients' quality of life is worse than dead (p < 0.001). Across all stages of disease, caregivers reported declines in HRQoL regardless of relationship; however, QALYs were highest in female caregiver–male patient dyads and lowest in female caregiver–female patient dyads. There were no significant differences in HRQoL or QALYs by FTD subtypes.

Table 4.

Health-related quality of life

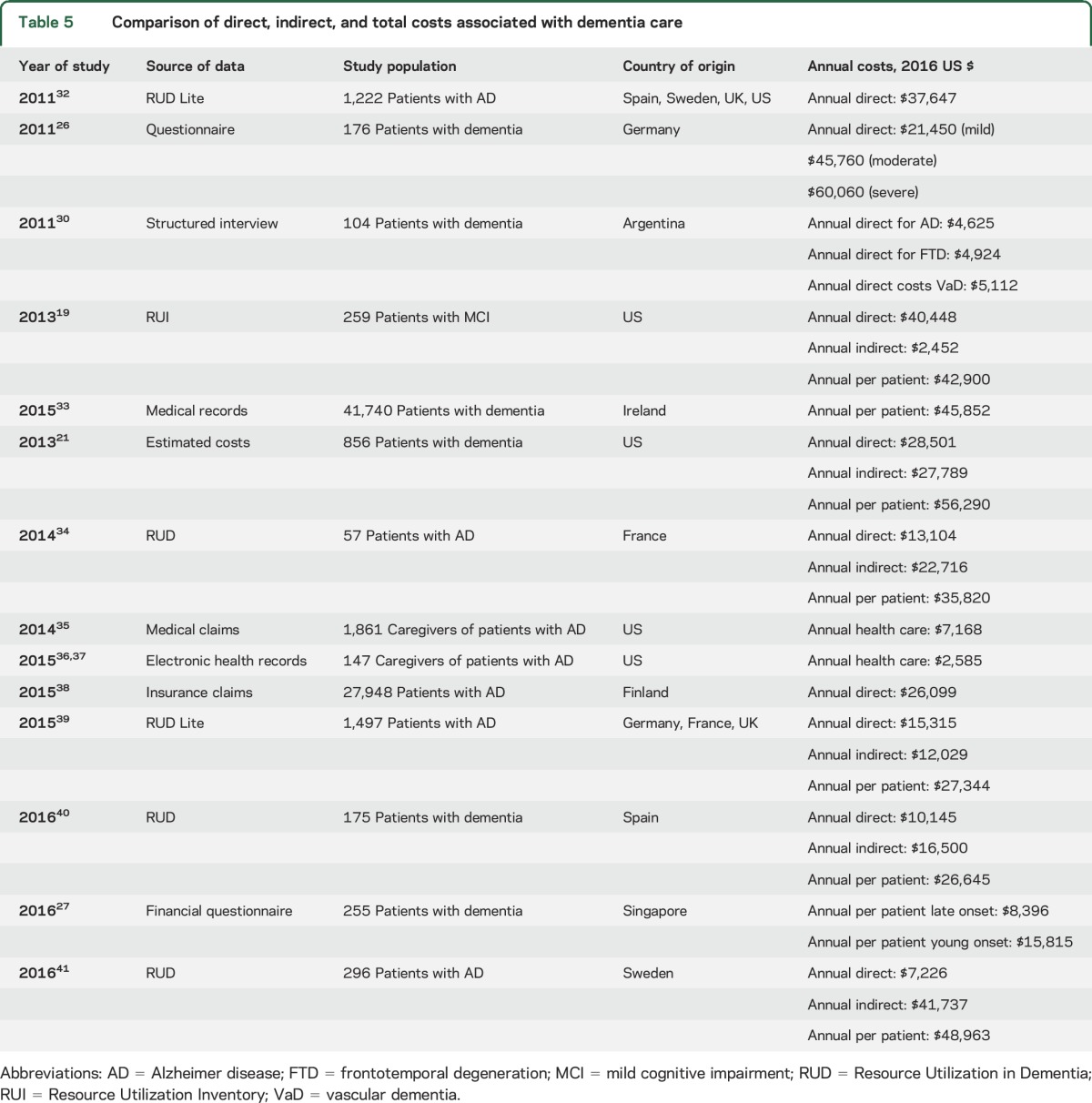

Comparison to economic costs of AD.

Lastly, we examined the cost analyses for annual direct, indirect, and total costs reported for patients with dementia in previous studies (table 5). Most of the cited studies examined patients with AD, mild cognitive impairment due to AD, or nonspecified dementia. These studies used a variety of data collection strategies, including record reviews, structured interviews, and validated scales. Studies from non-US sources were converted to 2016 US dollars for comparison. Reported costs were higher in more advanced stages of dementia26 and in younger-onset and non-AD dementias.19,27 Costs were greater in the United States than in studies originating in other countries. Most studies did not account for lost wages in the calculation of indirect costs and used HRQoL or QALYs to assess influence on quality of life. Across studies, inability to complete activities of daily living, worsening behavior, caregiver burden, the number of comorbid medical conditions, and increasing severity of disease were associated with higher costs.

Table 5.

Comparison of direct, indirect, and total costs associated with dementia care

One of the largest studies in the United States examining dementia costs21 used a subsample of 856 patients from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). This study reported a number of different cost estimates, which varied based on how unpaid care was valued and whether costs were adjusted for coexisting conditions, to report annual direct costs of $33,329 and annual indirect costs of $30,839 (total annual costs: $64,168). Their estimate of costs unadjusted for coexisting conditions with unpaid care valued at the replacement cost (i.e., the cost of hiring a paid home health worker) is comparable to our findings. However, overall costs of dementia care estimated from the HRS data were 53% lower than our reported total costs for FTD, or a total of $119,653.

DISCUSSION

FTD is associated with substantial direct and indirect costs, diminished quality of life, and increased caregiver burden. Most patients with FTD are working age, and most patients have to leave the labor force during their peak earning years. Caregivers of patients with FTD may also need to alter their careers to provide care. Combined, these factors contribute to a substantial decrease in household income. Previous studies have documented the heavy burden imposed by FTD on caregivers and families,28,29 but there has not been a study to date that captured the economic burden of FTD in the US.

A clinic-based study from Singapore27 that examined differences in median annual costs between young- and late-onset dementia reported young-onset dementia costs almost twice those of late-onset dementia in the clinic patient group ($15,815 vs $8,396). This same study found that FTD and vascular dementia had higher costs than young-onset AD. Another study in Argentina30 found annual direct costs for FTD to be higher than for AD, with at least part of that cost accounted for by psychotropic medications. Most studies have reported that resource use (institutional care, community care, home services) was highly correlated with dependency for activities of daily living and behavior. This is consistent with our finding that direct costs were significantly higher in bvFTD compared with other FTD subtypes.

Our study found that the economic burden for FTD in the United States is approximately twice that reported for AD.21 Given the age of the population affected by AD, the authors did not estimate productivity-related costs. When productivity-related costs are excluded and just direct costs and informal care costs are considered, our estimate of $69,000 per patient cost for FTD is similar to their estimate of the $64,000 per patient cost of AD dementia in the United States. However, because many patients with FTD and their caregivers would otherwise be in the labor force, the true per-patient economic burden of FTD may be substantially higher than for AD. It is worth noting that the reported AD per-patient care costs vary widely (table 5) and may reflect the impact that different methodologies have on generating cost estimates.

Our study has limitations. Individuals with an inherently positive view of research were more likely to respond to an invitation to participate. Not all individuals who initiated the survey completed the survey, but we found no sociodemographic differences between completers and noncompleters. We relied on self-reported resource use data, which may be subject to inaccurate recall. To counter this, we used well-accepted, validated instruments in dementia research (e.g., RUI and HUI3). Our sample population was caregivers rather than the patients themselves, and all diagnoses are self-reported. To overcome this, we used well-validated informant rating scales to assess presence and stage of dementia, activities of daily living, behavior, and HRQoL to characterize the patients. It is worth noting that in a disease with no formal clinical staging, caregivers' assessment of stage of disease strongly correlated across all validated staging, functional, and behavioral instruments. Finally, this study was cross-sectional and is unable to estimate longitudinal costs associated with disease progression.

Our finding of an increased economic burden for FTD compared to what is reported for AD may still underestimate true costs. Our cost estimates were based on items for which we could assign a unit cost to the item without making speculative assumptions and reasonably attribute the cost to FTD vs other illnesses. Therefore, while we measured caregiver's use of medical services, we did not assign a monetary value and could not determine what share of care is attributable to the unique burden of FTD caregiving without undertaking additional analyses.29

Although the absolute number of patients with FTD is lower than the number with AD, the economic burden of FTD is substantial. One of the key factors to this burden may be the earlier age at onset, typically occurring during patients' or caregivers' peak earning years. A better understanding of the substantial socioeconomic burden of FTD will provide the needed evidence base to help inform healthcare policy,31 to drive research agendas, and to enhance targeted allocation of resources that will lead to timely and accurate diagnosis and effective treatments where none now exists.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the many families who responded to the survey.

GLOSSARY

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- bvFTD

behavioral-variant frontotemporal degeneration

- CPT

Current Procedural Terminology

- FTD

frontotemporal degeneration

- HRQoL

health-related quality of life

- HRS

Health and Retirement Study

- HUI3

Health Utilities Index–3

- QALY

quality-adjusted life-years

- RUI

Resource Utilization Inventory

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr Galvin: study and questionnaire design, statistical analyses and interpretation, drafting, revising, and submitting the manuscript. Dr Howard: questionnaire design, statistical analyses, reviewing and editing the manuscript. Ms. Denny, Ms. Dickinson, and Dr Tatton: questionnaire design, reviewing and editing the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

This study was supported by a grant from the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration (Radnor, PA).

DISCLOSURE

J. Galvin serves as a scientific advisor for Axovant, Biogen, Eisai, and Eli Lilly; receives licensing fees from Pfizer, Lilly, Axovant, and Quintiles; and is funded by grants from the NIH (R01 AG0402-11-A1, U01 NS100610, and R01 NS088040-01), the Florida Department of Health, the Mangurian Foundation, and the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration. He is on the editorial boards of Neurodegenerative Disease Management, Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Disorders, and Acta Neuropathologica. D. Howard has served as a consultant for the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration and the Center for Discovery. S. Denny, S. Dickinson, and N. Tatton are employees of the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perry DC, Miller BL. Frontotemporal dementia. Semin Neurol 2013;33:336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2002;58:1615–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann DM. Frontotemporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:140–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knopman DS, Roberts RO. Estimating the number of persons with frontotemporal lobar degeneration in the US population. J Mol Neurosci 2011;45:330–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diehl J, Kurz A. Frontotemporal dementia: patient characteristics, cognition, and behaviour. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;17:914–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jicha GA, Nelson PT. Management of frontotemporal dementia: targeting symptom management in such a heterogeneous disease requires a wide range of therapeutic options. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2011;1:141–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012;2:a006239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onyike CU, Diehl-Schmid J. The epidemiology of frontotemporal dementia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2013;25:130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galvin JE. The Quick Dementia Rating System (QDRS): a rapid dementia staging tool. Alzheimer Dement 2015;1:249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000;12:233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol 1982;37:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbert R, Bravo G, Preville M. Reliability, validity, and reference values of the Zarit Burden Interview for assessing informal caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with dementia. Can J Aging 2000;19:494–507. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, Lippa CF, Taylor A, Zarit SH. Lewy body dementia: caregiver burden and unmet needs. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2010;24:177–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galvin JE, Duda JE, Kaufer DI, Lippa CF, Taylor A, Zarit SH. Lewy body dementia: the caregiver experience of clinical care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann PJ, Sandberg EA, Araki SS, Kuntz KM, Feeny D, Weinstein MC. A comparison of HUI2 and HUI3 utility scores in Alzheimer's disease. Med Decis Making 2000;20:413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kavirajan H, Hays RD, Vassar S, Vickrey BG. Responsiveness and construct validity of the Health Utilities Index in patients with dementia. Med Care 2009;47:651–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong T, Thokala P, McMillan B, Ghosh R, Brazier J. Cost effectiveness of using cognitive screening tests for detecting dementia and mild cognitive impairment in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry Epub 2016 Nov 22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Sano M, Zhu C, Whitehouse PJ, et al. ACDS Prevention Instrument Project: pharmacoeconomics: assessing health related resource use among healthy elderly. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:S191–S202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu CW, Sano M, Ferris SH, Whitehouse PJ, Patterson MB, Aisen PS. Health-related resource use and costs in elderly adults with and without mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:396–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genworth Cost of Care Survey [online]. Available at: https://www.genworth.com/about-us/industry-expertise/cost-of-care.html. Accessed December 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. DMEPOS fee schedule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/DMEPOSFeeSched/DMEPOS-Fee-Schedule.html. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- 23.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Home health aides. In: Occupational Outlook Handbook [online]. Available at: https://www.bls.gov.ooh/healthcare/home-health-aides.htm. Accessed December 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2015 national occupational employment and wage estimates United States: healthcare practitioners and technical occupations [online]. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm#29-0000. Accessed February 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2015 national occupational employment and wage estimates United States: all occupations [online]. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm#00-0000. Accessed December 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leicht H, Heinrich S, Heider D, et al. ; AgeCoDe Study Group. Net costs of dementia by disease stage. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;124:384–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kandiah N, Wang V, Lin X, et al. Cost related to dementia in the young and the impact of etiological subtype on cost. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;49:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caceres BA, Frank MO, Jun J, Martelly MT, Sadarangani T, Sales PC. Family caregivers of patients with frontotemporal dementia: an integrative review. Int J Nur Stud 2016;55:71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diehl-Schmid J, Schmidt EM, Nunnemann S, et al. Caregiver burden and needs in frontotemporal dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2013;26:221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas G, Bartoloni L, Dillon C, Serrano CM, Iturry M, Allegri RF. Clinical and economic characteristics associated with direct costs of Alzheimer's, frontotemporal and vascular dementia in Argentina. Int Psychogeriatr 2011;23:554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y, et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet 2015;385:549–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustavsson A, Brinck P, Bergvall N, et al. Predictors of costs of care in Alzheimer's disease: a multinational sample of 1222 patients. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Connolly S, O'Shea E. The impact of dementia on length of stay in acute hospitals in Ireland. Dementia 2015;14:650–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gervès C, Chauvin P, Bellanger MM. Evaluation of full costs of care for patients with Alzheimer's disease in France: the predominant role of informal care. Health Policy 2014;116:114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suehs BT, Shah SN, Davis CD, et al. Household members of persons with Alzheimer's disease: health conditions, healthcare resource use, and healthcare costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu CW, Scarmeas N, Ornstein K, et al. Health-care use and cost in dementia caregivers: longitudinal results from the Predictors Caregiver Study. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:444–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein K, et al. Medicare utilization and expenditures around incident dementia in a multiethnic cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015;70:1448–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tolppanen AM, Taipale H, Purmonen T, Koponen M, Soininen H, Hartikainen S. Hospital admissions, outpatient visits and healthcare costs of community-dwellers with Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodel R, Belger M, Reed C, et al. Determinants of societal costs in Alzheimer's disease: GERAS study baseline results. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:933–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farré M, Haro JM, Kostov B, et al. Direct and indirect costs and resource use in dementia care: a cross-sectional study in patients living at home. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;55:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Åkerborg Ö, Lang A, Wimo A, et al. Cost of dementia and its correlation with dependence. J Aging Health 2016;28:1448–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]