Abstract

Public health research has indicated extremely high HIV seroprevalence (13–63%) among low-income transfeminine people of color of African, Latina, and Asian descent living in the U.S. This paper combines two data sets. One set is based on an ethnographic study (N=50, 120 hours of participant observation). The other set longitudinal quantitative study (baseline N=600, N=275 followed for 3 years). Transfeminine people of color are much more likely to be androphilic and at high HIV risk. A greater understanding of adolescent gender-related abuse and trauma-impacted androphilia contributes towards a holistic conceptual model of HIV risk. A theoretical model is proposed that incorporates findings from both studies and integrates sociostructural, interpersonal, and intrapsychic levels of HIV risk.

Keywords: androphilia, childhood abuse, developmental, diachronic analysis, gender identity, gender-related abuse/violence, HIV risk, life course perspective, low-income, mental health, people of color, poverty, re-traumatization, sex work, sexual health, social determinants of health, social ecology, transgender, transwomen of color, victimization

Public health research has shown evidence of extremely high HIV seroprevalence (13–63%) among low-income transfeminine (male-to-female trans/gender-variant) people of color (POC) of African, Latina, and Asian descent living in the U.S. The authors of this article carried out a five-year study on transfeminine-spectrum individuals in New York City from 2004–09 and found 48% seroprevalence for African Americans and 49% for Latinas (Nuttbrock et al., 2009, see Table 1). Much of the high HIV seroprevalence has been attributed to participation in survival sex work and infection from primary non-commercial male partners (Nemoto et al., 2004a, 2004b; Nuttbrock et al., 2009; Sausa et al., 2007).

Table 1.

HIV Prevalence of Transfeminine People by Racial Categories (Percentages)

| Race | Prior Studies | NYC Study |

|---|---|---|

| African American | 41 – 63 | 48 |

| Latina | 23 – 29 | 49 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 – 27 | 20 |

| Euro-American | 3 – 22 | 3 |

(Nemoto et al. 1999, 2004a, 2004b; Clements-Nolle et al. 2001; Kenagy 2005; Kellogg et al. 2001; Nuttbrock et al. 2009a)

Although “transwomen” is often utilized in public health discourse to refer to all male-to-female trans/gender-variant people (Koken et al., 2009; Sausa et al., 2007), in this article we utilize the term “transfeminine” to refer to individuals along the “transfeminine spectrum” of individuals assigned male at birth who now identify partially or fully as female and/or women. In our studies, we encountered a wide variety of self identifications such as bakla, cross-dresser, feminine male, fem queen, gender-fluid, kathoey, queen up in drags, reina, t-girl, transfemale, transvestite, transwoman, travesti, and woman, and the term “transfeminine” is intended to be inclusive of all these identities. Complex part-time and full-time transfeminine identities were especially observed in POC and/or immigrant populations, and some of these complex identities have been discussed in other studies (Gilley, 2006; Hwahng & Lin, 2009; Hwahng & Nuttbrock, 2007; Johnson, 1997; Kulick, 1998; Prieur, 1998). The purpose of this article is to propose a holistic theoretical model of HIV risk for low-income transfeminine POC that is supported by data from two studies. It extends existing research and scholarship on trans sexualities by incorporating sociostructural, interpersonal, and intrapsychic factors.

Preliminary Conceptual Frameworks

A current trend in public health is the emphasis on the importance of the “social determinants of health” and particularly “upstream” (socio-structural) as well as “midstream” (health behavioral) social determinants. A further elaboration of the social determinants of health concept can be found in a recent National Institutes of Health-funded Institute of Medicine report on LGBT heath that emphasized “the social ecology model” in which the social environment affects health behavior and vice versa (IOM, 2011). A social ecological model has multiple levels and the model includes not only the individual but also families, relationships, community, and society.

The report also emphasized the “minority stress model,” in which LGBT people experience chronic stress arising from their stigmatization. Distal stress refers to actual external experiences of discrimination and violence whereas proximal stress refers to internalized homo- or transphobia, perceived stigma, and concealment of one’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Another focus was on “intersectional perspective,” in which simultaneous dimensions of inequality are examined, including how these dimensions are interrelated and how they shape and influence one another. “Understanding the racial and ethnic experiences of sexual- and gender-minority individuals requires taking into account the full range of historical and social experiences both within and between sexual- and gender-minority groups with respect to class, gender, race, ethnicity, and geographical location” (IOM, 2011, 21, italics added).

Finally, the importance of a “life course perspective” was discussed. Central to a life-course perspective/framework (Cohler and Hammack, 2007; Elder, 1998) is the notion that the experiences of an individual at every stage of their life inform subsequent experiences at a later life-stage, since an individual may be constantly revisiting issues encountered at earlier points in the life course. The IOM report also stated that this interrelationship among experiences started before birth and in fact, before conception of a given individual (20, italics added). Thus, this statement emphasizes the powerful linkage between individuals and the historical and socioeconomic context in which their lives unfold. Furthermore, not only the individual, but also the family is contextualized, in which the family is considered a micro-social group with a macro-social context.

It is useful, then, to consider the concept of “historical trauma” to fully contextualize individuals and families within their historical and socioeconomic contexts. For POC these historical and socioeconomic contexts must also be racialized in order to foreground racial- and ethnic-specific historical and socioeconomic conditions that impact/influence the lives of POC. One pivotal body of public health literature that has explored racialized historical and socioeconomic conditions in relation to sexual minority and gender-variant behaviors and HIV risk has focused on Native American two-spirit people. Although the focus of this article is not on Native Americans, it is useful to consider this literature in order to examine how social contexts for other groups, such as African Americans and Latinas, may be more fully racialized. “Two-spirit” is a distinctly Native American category that includes individuals who are sexual minority as well as individuals who are gender-variant, and often the two categories overlap, in which “two-spirit” may be considered more of a “gender role” and “spiritual/social role” rather than a sexual identity (Allen, 1986; Gilley, 2006; Lang, 1998; Roscoe, 1998; Tafoya, 1997; Vernon, 1992). Thus, the category of “two-spirit men” includes individuals who would be categorized in public health discourse as MSM as well as transfeminine people/transwomen.

In order to fully measure the traumatic stressors two-spirit people may be encountering, researchers developed an innovative “historical trauma” scale that was operationalized to measure how much Native American individuals remembered Native American-specific historical trauma, such as factors associated with genocide, colonization, forced relocation, and removal of burial sites, and how these traumas affected members of their families/blood lineages, including parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and siblings (Balsam et al., 2004; Simoni et al., 2006). More conventional scales were also utilized to measure lifetime experiences of physical and sexual victimization, as well as mental health, substance use, and high-HIV risk sexual behaviors.

Comparing two-spirit men to heterosexual men revealed that two-spirit men scored higher on an overwhelming majority of all scales, and scored significantly higher on three historical trauma measures, childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and two intimate partner violence measures. Two-spirit men also scored significantly higher on anxiety and PTSD measures, four substance use measures, and nine out of ten high-HIV risk sexual behaviors (Balsam et al., 2004; Simoni et al., 2006). The researchers concluded that two-spirit men were experiencing disproportionately burdensome stressors not only from their own lifetime victimization experiences, but also because of the greater extent to which they were affected by the inter-generational transmission of historical trauma through their memory/experience of said trauma. Thus, historical trauma compounded the lifetime stressors of victimization resulting in overwhelming negative feelings that two-spirit male survivors attempted to assuage through substance use and high-risk sexual behaviors, as well as experiencing higher levels of negative mental health. Interpreting this research also reveals this phenomenon: historical trauma may give rise to inter-generational transmission of trauma; inter-generational transmission of trauma may manifest in family dynamics, such as targeted abuse of children who are gender atypical and/or sexual minority. Thus, gender- and sexual minority-related victimization by family members may be related to larger structural factors, and may be a form of historical trauma transmission.

What has increasingly become apparent in public health is that the co-morbidities of negative mental health outcomes and increased HIV risk may both be attributed to the same or similar social determinants of health, with an increasing focus on “upstream” social determinants. However, another important social determinant of health is the concept of adult re-traumatization in which an individual who experienced victimization during the vulnerable developmental periods of childhood and/or adolescence will unwittingly participate in behaviors that attempt to assuage negative feelings associated with the victimization (such as substance use or high-risk sexual behaviors) and yet often places the individual in conditions that may “re-traumatize” said individual. Thus, the individual may find herself/himself endlessly enmeshed in a cycle of trauma, violence, and coping strategies that only temporarily placates negative feelings. Minority stress that may have originated externally, then, thus becomes internalized minority stress/stigma.

What is interesting about the adult re-traumatization concept is that, if linked to paradigms such as historical trauma, this concept may actually provide a more comprehensive understanding of low-income LGBT POC by connecting upstream social determinants, social ecology, intersectionality, and life-course perspective conceptual frameworks. Although adult re-traumatization as a mechanism for high-HIV risk has not yet been applied to trans/gender-variant populations, it has been significantly proven as a mechanism to explain high levels of substance use, victimization, negative mental health, and high-HIV risk behaviors among MSM and women who have sex with women (WSW) populations, including low-income MSM of color (Arreola et al., 2008; Arreola et al., 2009; Austin et al., 2008; Balsam et al., 2004; Descamps et al., 2000; D’Augelli et al., 2006; Hall, 1996; Hershberger et al., 1995; Saewyc et al., 2006; Scheer et al., 2003; Williams et al., 2008).

Method

Two data sets were examined from the New York Transgender Project. One set was based on an 18-month (2005–06 and 2012) ethnographic study of HIV risk among transfeminine communities (N=50, 120 hours of participant observation) initiated and conducted by the first-author. Details of the methods of the ethnographic study have been previously published (Hwahng & Nuttbrock, 2007). Additional in-depth qualitative interviews (N=5) were conducted in 2012 to supplement the findings from the 2005–06 study. The other set is a five-year (2004–09) longitudinal quantitative study (N=571 transfeminine people at baseline; N=275 tracked for 3 years) funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The life chart interview (Lyketsos, 1994) was adapted for transfeminine persons (LCI-TE) and gathered current and retrospective data from the age of 10 years, dividing the life course into five stages. Participants were asked similar questions for each life stage, which included their relationships, transfeminine identity development, gender-related abuse/victimization, depression and suicidality, substance use, and HIV/STI risk behaviors and testing. Early adolescence was defined as 10–14 years of age (Life Stage 1), and late adolescence was defined as 15–19 years of age (Life Stage 2). Both the ethnographic and quantitative studies were approved by the IRB at National Development and Research Institutes, Inc.

Findings

Ethnographic Study: Racial Stratification and Socio-Structural Factors of HIV Risk

One of the major findings was that racial stratification seemed to be a central organizing principle in determining access to resources and institutional benefits (Hwahng & Nuttbrock, 2007). Euro-Americans were privileged over immigrant Southeast Asians, and immigrant Southeast Asians were privileged over non-immigrant African Americans and Latinas in this sample. African Americans and Latinas were thus positioned at the bottom of the racial stratification hierarchy. Among nine factors related to both economic and HIV vulnerability, African Americans and Latinas manifested evidence of the highest vulnerabilities overall in terms of both economic and HIV vulnerability.

Another finding was that the overwhelming majority (over 90%) of clients of the transfeminine sex workers of color in our sample were reportedly Euro-American, middle-class, heterosexually-identified, cisgender1 males. Racial stratification, along with trans/gender-variant stigma, thus provided sexual markets for these cisgender men by continually marginalizing low-income transfeminine POC who would then become dependent on sex work for their economic survival. Racial stratification was also socially protective of these Euro-American male clients because it facilitated these cisgender men’s “double life.” These male clients were able to procure sexual services in neighborhoods/enclaves geographically distant from the neighborhoods/enclaves where they lived. Thus, there was little to no possibility of any social “contamination” via low-income transfeminine sex workers of color entering into their social networks and revealing their commercial and “non-normative” sexual interactions (Hwahng & Nuttbrock, 2007).

At the time the initial phase of the ethnographic study was conducted (2005–06), there was a belief among public health researchers that sex work may have been a major route of HIV transmission to low-income transfeminine POC, although some researchers also identified non-commercial male partners as another possible major transmission vector (Nemoto et al., 2004a, 2004b). Presently, it is believed that non-commercial male partners may be the most direct and major route of transmission, particularly a group known as men of color who have sex with men and women (MSMW of color), many of whom appear to partner with transfeminine POC in non-commercial primary and casual relationships (Melendez & Pinto, 2007; Pettiway, 1996).

Our ethnographic study provides further support for this present supposition. Since there is no indication of high HIV seroprevalence among Euro-American cisgender heterosexually-identified men in NYC (the primary client base of transfeminine POC sex workers), it does appear that infection from male clients is not a major route of transmission. In contrast, one group that has very HIV seroprevalence in the U.S. is “men of color who have sex with men (MSM of color),” which does include MSMW of color as discussed above (Gorbach et al., 2009; Latkin et al., 2011; Maulsby et al., 2012; Saleh et al., 2011)2. In fact, male partners of color who partner with transfeminine POC may be at even higher HIV risk compared to other MSM of color (Bockting et al., 2007; Pettiway, 1996). Since there is an HIV epidemic among both MSM of color and transfeminine POC, there may be an association of HIV risk between the two groups, and that transmission is occurring between at least some members or sub-groups of the two groups.

Survival sex work may be important, then, as a moderating factor but not a mediating factor for HIV transmission. Participation in survival sex work may render transfeminine POC vulnerable to gender-related victimization, sexual and gender objectification/trivialization, and reinforcement of low self-worth, which may also then exacerbate negative mental health outcomes such as depression and suicidality. These processes and outcomes may thus have an impact on transfeminine POC’s sense of self-esteem and consequent ability to select male partners and relationships that are low-HIV risk and self-affirming, and to process HIV risk information and negotiate condom use with these male partners. The findings further illustrate how the intertwining of sexual attraction to cisgender men and gender-related abuse during adolescence may also negatively impact transfeminine POC’s self-esteem and life choices.

Androphilia and Gender Identity

One of the goals of data collection for the quantitative study was to generate a diverse sample with regard to race and age so that between-group comparisons could be made. After utilizing multiple recruitment strategies, the results indicated that the transfeminine POC subsample was much younger than the Euro-American subsample. Examining Table 2 reveals that, among those 19–39 years of age, 87% were transfeminine POC. In contrast, among those 40–59 years of age, 53% were transfeminine POC. Targeted strategies to recruit younger Euro-Americans, especially those who were low-income, yielded low returns. This sample would suggest that the majority of transfeminine people in NYC are POC who are younger than 40 years of age.

Table 2.

Breakdown of the Sample by Current Age and Racial Categories (Percentages)

| Current Age | ||

|---|---|---|

| 19 – 30 (n = 323) |

40 – 59 (n = 233) |

|

| African Americana | 26.0 | 16.0 |

| Latinab | 55.0 | 31.0 |

| Euro - Americanc | 13.0 | 48.0 |

| Otherd | 6.0 | 5.0 |

Total N = 556.

Racial categories were determined using the protocols and terminology employed by the US Census Bureau.

Non-Hispanic Black.

Hispanic.

Non-Hispanic White.

All other Non-Hispanic Identifications

Another important finding from the quantitative study was the high levels of exclusive androphilia (being attracted to and partnering with only cisgender men) reported by transfeminine POC. Participants were asked four questions to measure sexual orientation: with whom one currently has sex, to whom one is sexually attracted, about whom one currently has sexual fantasies, and with whom one can fall in love. There were six options for partners for each question, including two cisgender, four trans/gender-variant/transsexual, and one intersex option. A majority (62.3%) of POC chose only cisgender men across the four questions, with 90–91% of African Americans and Latinas choosing only cisgender men. In contrast, only 19.9% of Euro-Americans chose only cisgender men across the four questions (see Table 3). Androphilia is highly correlated with POC, especially African Americans and Latinas (see Nuttbrock et al. 2011 for associations of gynephilia. i.e. attraction to cisgender women, with Euro-American ethnicity among the transfeminine population).

Table 3.

Androphilic Sexual Orientation by Racial Identification

| Percentage Androphilica | |

|---|---|

| African American (n = 120) | 90.0 |

| Latina (n = 244) | 91.1 |

| Other (n = 53) | 62.3 |

| Euro - American (n = 144) | 19.9* |

Percentages do not total 100.0

Total N=556.

P<=.01 (χ2 of Euro-American compared to all other racial categories).

Sexual attraction exclusively to cisgender men.

Many studies among transfeminine POC in Latin America, Africa, and Asia also reveal a strong association between transfemininity and androphilia (Gilley, 2006; Johnson, 1997; Kulick, 1998; Prieur, 1998; Reddy, 2005). Of particular importance is Kulick’s (1998) study of Afro-Brazilian travestis in Salvador, Brazil. Kulick noted that gender identity development seemed to either coincide with awareness of attraction to cisgender men, or that gender identity development occurred soon after awareness of androphilic attraction. Kulick surmised that for travestis, gender identity was dependent upon a “developmental homosexuality” in which their attraction to males was an intrinsic and motivating force for their development of gender identity (48–52). Although Kulick used the term, “developmental homosexuality,” it is perhaps more precise to label this phenomenon “developmental androphilia,” since both the travestis Kulick studied and the transfeminine individuals in our NYC study considered themselves a different sex/gender3 compared to the cisgender men to whom they were attracted. Kulick found that travestis were overwhelmingly attracted to young, handsome, masculine-appearing, low-income men of color who were often heterosexually-identified or non-identified in terms of their sexual orientation.

What is striking is the very similar evidence in the NYC studies supporting a developmental androphilia model for transfeminine African Americans and Latinas. For instance, Chandelle4 (Latina and African American, 19 y.o.) stated that she first became aware of her transfeminine identity when she was “about eight years old” and also became aware of her attraction to males when she was seven years old. Her first male partner was “very masculine… He’s what I call a daywalker… [He] can walk with the crowds… and not get clocked. Versus me with my feminine switch and being overly feminine… He was masculine and I was feminine… Feminine men are in a different gender category than masculine men.” Chandelle also elaborated how an individual’s gender category was dependent on “what they liked.” That is, an individual’s attraction to masculine or feminine men and/or women would determine the gender category of that individual.

Tawana (African American, 21 y.o.) stated that being with a “masculine man” completed and supported her femininity as “the full mission… I like macho men. I like strong, masculine men… what we call the ‘trade’… kind of [heterosexual]. The trade gets down with some [gays] on the DL [down low]… To be honest with you, I like men who are straight… The closest to that are men on the DL… because I have a certain preference. It goes with the femininity.” Amanda (African American, 20 y.o.) also confirmed that she was attracted only to “rough and real” masculine men “from the streets”; she dismissed all masculine-dressed males who “hung out” in the [drag] Ball scene as “butch queens,” whom she did not find attractive. She explained that all “queens”—“fem queens, queens up in drags [sic], and butch queens”—were “after the same thing… men” (i.e., attracted to “real” masculine men).

Marcella (African American, 22 y.o.) discussed the importance of gender difference in romantic relationships:

I don’t like feminine boys… It’s like you’re with your homegirl and kissing… If you put two girly-girls in the room, what are they to do? We both like the same thing. We like to do the same… How are we to please each other?… With a [cisgender] woman, it scares me. I think of women as a mom figure… Sometimes when I think [of having sex with a cisgender woman] uggghh [repulsed sound]… [cisgender] pussy’s nasty… I won’t do something with [pussy]…”

In addition, Amanda also viewed cisgender women as “competition” in the realm of femininity. Marcella described roles that she enjoyed in specific sexual acts that complemented the roles a masculine male partner would fulfill, including various types of foreplay, anal rimming, and oral/anal intercourse. She also considered receptive oral/anal intercourse part of a feminine sexual repertoire that she enjoyed. Other participants also confirmed that they enjoyed the receptive sexual role and found it strange if a masculine male partner did not take on the insertive role.

Gender-Related Adolescent Abuse

In Nuttbrock et al., 2009, 78.1% and 50.1% of all transfeminine participants reported some form of psychological and physical gender-related abuse, respectively, during their lifetime. It was also reported that perpetrators of abuse during adolescence were mostly parents or other family members, whereas perpetrators post-adolescence were most often strangers, neighbors, friends, or police officers. A “dose-response” association was observed between abuse and depression, and abuse and suicidality, during early and late adolescence, with associations particularly strong in early adolescence. This meant that the prevalence of depression and suicidality was roughly twice as high among those who were periodically abused compared to not abused and, in turn, twice as high among those who were persistently abused compared to periodically abused. This type of strong association could thus be inferred as a “casual mechanism” in which abuse predicted and was causal for depression. After adolescence, however, there was no consistent association between abuse and depression.

It appeared that adolescence was a particularly vulnerable developmental period in the life course and abuse had a particularly strong effect on mental health. After adolescence, adults may have developed more resilience to cope with abuse, although, in particular, persistent adult abuse was often associated with depression and suicidality (see Nuttbrock et al., 2010). If adolescence was a particularly vulnerable time for transfeminine individuals, those who were discovering their gender identity through developmental androphilia may have been especially affected. That is, abuse may have resulted in not only greater depression and suicidality during adolescence, but may have also negatively impacted a developmentally androphilic transfeminine identity that was forming during adolescence and this negative impact may have extended into adulthood.

Certainly, the quantitative data provides ample evidence of high rates of abuse among transfeminine POC, with African Americans, Latinas, and other POC reporting 76.9%, 80.9%, and 78.7% lifetime psychological abuse, respectively, and 54.5%, 55.3%, and 57.4% lifetime physical abuse, respectively. All three POC groups also reported significantly higher lifetime physical abuse compared to Euro-Americans (Nuttbrock et al., 2010). Specifically examining the period of adolescence reveals further racial disparities. Table 4 reveals that a majority of transfeminine POC reported experiencing abuse in both early and late adolescence. 57.4% and 59.8% of African Americans reported experiencing verbal and/or physical abuse in their early and late adolescence, respectively, while 65.4% and 60.6% of Latinas reported experiencing verbal and/or physical abuse in their early and late adolescence, respectively. In comparison, less than half of Euro-Americans, 38.3% and 28.6%, respectively, reported experiencing verbal and/or physical abuse in their early and late adolescence.

Table 4.

Gender Abuse during Early and Late Adolescence by Racial Categories and Current Age (Percentages)

| Verbal | Physical | Verbal or Physical | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EARLY ADOLESCENCE (age 10–14) | |||

| Racial Category/Current Age | |||

| African American | |||

| 19 – 59 (121) | 54.1 | 35.2 | 57.4 |

| 19 – 39 (84) | 54.8 | 35.7 | 58.3 |

| 40 – 59 (37) | 54.1 | 35.1 | 65.4 |

| Latina | |||

| 19–59 (250) | 62.2 | 32.1 | 65.4 |

| 19–39 (176) | 59.7 | 30.1 | 63.1 |

| 40–59 (74) | 68.6 | 37.1 | 71.4 |

| Euro-American | |||

| 19–59 (154) | 34.4* | 23.4* | 38.3* |

| 19–39 (43) | 51.2* | 25.6* | 51.2* |

| 40–59 (111) | 27.0* | 14.4* | 27.0* |

| LATE ADOLESCENCE (age 15 – 19) | |||

| Racial Category/Current Age | |||

| African American | |||

| 19 – 59 (121) | 58.2 | 30.3 | 59.8 |

| 19 – 39 (84) | 57.1 | 31.0 | 59.5 |

| 40 – 59 (37) | 59.5 | 29.7 | 59.5 |

| Latina | |||

| 19 – 59 (250) | 57.7 | 29.3 | 60.6 |

| 19 –39 (176) | 55.1 | 25.6 | 57.4 |

| 40–59 (74) | 64.3 | 38.6 | 68.6 |

| Euro-American | |||

| 19–59 (154) | 27.9* | 14.9* | 28.6* |

| 19–39 (43) | 30.2* | 16.3* | 32.6* |

| 40–59 (111) | 27.0* | 14.4* | 27.0* |

Percentages based on sub-sample sizes indicated in parentheses.

P<=.01 (χ2 of Euro-American compared to the other racial categories, within the indicated age groups).

Further analysis also revealed ethnic differences in relation to reported perpetrators of abuse during adolescence. Previous literature has discussed the importance of families of color as a protective mechanism against racism, poverty, and other harsh circumstances in life, and close connections to family members help to bolster self-esteem, leading to positive health (including mental health) outcomes (Brown, 2008; Pettiway, 1996; Prieur, 1998, Rivera, 2007). Thus, for POC, abuse, neglect, and/or ostracism related to their gender identity and/or sexual orientation by parents and other family members may have had a devastating impact (Diaz, 1998; Rivera et al., 2008), especially if this abuse, neglect, and/or ostracism occurred during the vulnerable time of adolescence and gender/sexual identity development (Kulick, 1997; Pettiway, 1996; Prieur, 1998). As a result, many young transfeminine POC may have found themselves homeless and on the streets either because they were forced out of their homes, or they voluntarily left because the levels of abuse, violence, and stress were unbearable (Koken et al. 2009; Pettiway 1996). And even if they had remained in their biological family homes, they may have been subject to psychological and emotional stressors with lasting negative impacts.

Table 5 shows that African Americans (27%) and Latinas (30.5%) reported experiencing significantly more gender-related abuse perpetrated by family members during early adolescence compared to Euro-Americans (16.2%). During late adolescence, African Americans (29.1%) and Latinas (31%) also reported experiencing significantly more gender-related abuse perpetrated by family members compared to Euro-Americans (14.1%).

Table 5.

Gender Abuse by Family Members during Early and Late Adolescence, Computed for the Total Sample and across Categories of Race (Percentages)

| Verbal | Physical | Verbal or Physical | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EARLY ADOLESCENCE (age 10-14) | |||

| Total Sample (556) | 22.0 | 14.8 | 25.6 |

| Race | |||

| African American (121) | 22.1 | 20.5 | 27.0 |

| Latina (250) | 26.4 | 15.9 | 30.5 |

| Euro-American (154) | 14.3* | 7.1* | 16.2* |

| LATE ADOLESCENCE (age 15–19) | |||

| Total Sample (556) | 13.1 | 14.7 | 28.2 |

| Race | |||

| African American (121) | 16.4 | 20.5 | 29.1 |

| Latina (250) | 15.4 | 15.6 | 31.0 |

| Euro-American (154) | 7.1* | 7.0* | 14.1* |

Percentages based on sample or sub-sample sizes indicated in parentheses.

P<=.01 (χ2 of Euro-American compared to the other racial categories, within the stages of adolescence).

Since abuse could be inferred as a causal mechanism for depression and suicidality during adolescence, an ethnic breakdown reveals that during early adolescence 30.3% African Americans, 40.2% Latinas, and 22.1% Euro-Americans reported experiencing major depression. During late adolescence, 21.5% African Americans, 27.9% Latinas, and 26% Euro-Americans reported experiencing major depression. During early adolescence, 29.1% African Americans, 29.8% Latinas, and 16.7% Euro-Americans reported experiencing suicidality. During late adolescence, 27.3% African Americans, 20.5% Latinas, and 28.8% Euro-Americans reported experiencing suicidality (Table 6).

Table 6.

Major Depression and Suicidal Ideation during Early and Late Adolescence, Computed for the Total Sample and across Categories of Racial Identification (Percentages)

| Major Depression | Suicidal Ideation | |

|---|---|---|

| EARLY ADOLESCENCE (age 10–14) | ||

| Total Sample (556) | 31.8 | 25.6 |

| Racial Identification | ||

| African American (121) | 30.3 | 29.1 |

| Latina (250) | 40.2 | 29.8 |

| Euro-American (154) | 22.1* | 16.7* |

| LATE ADOLESCENCE (age 15–19) | ||

| Total Sample (556) | 25.2 | 24.1 |

| Racial Identification | ||

| African American (121) | 21.5 | 27.3 |

| Latina (250) | 27.9 | 20.5 |

| Euro-American (154) | 26.0 | 28.8 |

Percentages are based on sample or sub-sample sizes indicated in parentheses.

P<=.01 (χ2 of Euro-American compared to the other racial categories, within the stages of adolescence).

What is interesting to note, then, is that during early adolescence, African Americans and Latinas reported experiencing significantly higher levels of depression and suicidality compared to Euro-Americans. During late adolescence there were no significant differences in reports of depression/suicidality among the racial groups (despite African Americans and Latinas reporting both higher levels of gender-related abuse and higher levels of abuse perpetrated by family members compared to Euro-Americans during late adolescence). This may point to the saliency of alternative gay/transfeminine kinship networks that are racially-/ethnically-specific, such as the Ball community or immigrant Latina social networks, which provided a certain amount of social support built on “thick trust”5 that may have tempered the exorbitantly high rates of reported depression and suicidality among African Americans/Latinas during early adolescence (Hwahng et al., 2012).

More research is needed to understand why reported depression and suicidality increased for Euro-Americans, but perhaps Euro-Americans were more likely to become aware of their gender identity later in adolescence, which may have then caused greater distress during late adolescence. There also appeared to be a dearth of “thick trust” transfeminine social networks for Euro-Americans (Hwahng & Nuttbrock, 2007), in which “thick trust” transfeminine social networks may serve to buffer against depression/suicidality (Hwahng & Nuttbrock, 2012).

Despite the relatively lower levels of reported depression and suicidality during late adolescence among African Americans and Latinas, the levels were still high when compared to the national average of 5% major depression among adolescents in the U.S. (Bhatia & Bhatia, 2007). Thus, the very high levels of reported depression and suicidality in both early and late adolescence may have actually been co-morbidities and symptomatic of other types of negative psychological processes that were formed during adolescence through the perpetration of abuse.

Trauma-Impacted Androphilia, Loss of Power, and HIV Risk

During adolescence, a majority of transfeminine POC in our sample reportedly developed a sexual identity that was deeply androphilic, yet were also subjected to abuse directed toward their transfemininity and androphilia. The data show that much of the abuse was reportedly perpetrated by parents and other family members who, up to that time, may have been a main source of social, emotional, and psychological support in a racially-hostile society. This raises the possibility of associations between abuse, loss of social/emotional/psychological support, transfemininity, and androphilia emerging from these developmental/life history intersections.

For transfeminine POC specifically, might the trauma of abuse experienced during adolescence manifested as a trauma-impacted androphilia, in which they unwittingly participated in a cycle of re-traumatization as adults? Such re-traumatization may have resulted in susceptibility to further abuse/victimization, stigmatization of their transfemininity, low self-esteem, loss of power in romantic and sexual relationships with men, and the use of alcohol and other drugs to help cope with stigma, trauma, and disempowerment. All of these factors could have contributed to or exacerbated HIV risk. As such, the concept of a trauma-impacted androphilia may be productive for conceptualizing and addressing high HIV seroprevalence pathways among transfeminine POC.

Indeed, the qualitative data provide evidence for this risk trajectory by revealing dynamics experienced in participants’ romantic/sexual relationships with men, which often involved reports of exploitation, abuse, victimization, and loss of power. For instance, Sharon (Latina, 35 y.o.), a former sex worker, stated:

And I had a boyfriend… I was in love and the only way that I kept him happy was when he wanted his drugs and I went out there and got it for him, you know. So he didn’t care how I did it as long as he had it…[To boyfriend:] ‘If you don’t care how I go and make money to get your drugs then, obviously, the drug is more important to you than I am.’

Sharon described participating in extremely risky street-based sex work in order to support herself, her male partner, and his drug use. A common pattern observed among transfeminine POC in our sample was that they often reported financially supporting their male partners, and street-based sex work was often one of the fastest and most accessible routes for lucrative employment.

In fact, among low-income POC in our sample, it seemed to be common knowledge that many, if not a majority, of young, transfeminine POC participated in street-based sex work and may have had some discretionary income. Male partners of sample participants were largely heterosexually-identified or non-identified masculine-appearing low-income men of color. Given the economic disenfranchisement and criminalization of low-income men of color, some may have viewed romantic relationships with transfeminine POC as a viable means of economic support. Nadia (African American, 23 y.o.) affirmed this by stating:

A lot of times, in the Ballroom scene, a lot of the [heterosexually-identified or non-identified] guys that go there…[go there] because they know they’re going to meet some queens there. Or, they know that transsexuals have money that they’ll spend. And they know [fem queens] make good money from sex work, usually.6

Priscilla (African American, 24 y.o.) also confirmed: “[T]hey might be supporting a boy from their neighborhood…who they really like… They could be bugged out… [The husbands] are from the streets… they’re heterosexual.” Belinda (African American, 25 y.o.) also revealed that in romantic relationships, it was often the male partners who held the upper hand in relationships: “I think that’s one thing—with the boys that are Black and Latin—that fem queens have to deal with…’cause [boys] know they can make them girls fall in love.”

Carla (African American, 20 y.o.) revealed disturbing information about her own experience:

I’ve been raped by boys in the hood… But I’ve also been raped by boys in the Ballroom scene… I would go out with them and hang out and that’s not a really safe thing for me to do—not because I’m stupid or because I’m dumb or I’m a ho or I’m a slut… Just because… for them to think that I am single… So they feel like they could just do what they wanted to do and I didn’t feel like they couldn’t.

In this case, Carla’s loss of power in relationships was taken to such an extreme that there was reportedly a tacit understanding that she would willingly submit to the sexual violence perpetrated against her. Tanya (African American, 26 y.o.) discussed engaging in sexual encounters with multiple partners for economic and other reasons: “If I had a husband and we lived together and I go somewhere and another boy tries to talk to me and says he’ll give me money… I’ll sleep with him even if I’m in love with the boy back home… There’s just something about it that would make me want to do it.” Participants in our sample also reported that exploring their gender and sexuality across primary, casual, and commercial/transactional relationships, and androphilic pursuits with multiple partners may have been pleasurable and gender-affirming (see also Pettiway, 1996). Concurrent sexual partners, however, were also associated with high HIV risk (Nemoto et al., 2004a, 2004b; Nuttbrock et al., 2009). As such, it is imperative that transfeminine African Americans/Latinas are sufficiently supported to consistently engage in HIV risk information processing and condom negotiation/use with male sexual partners.

A Holistic Model for HIV Risk among Transfeminine POC

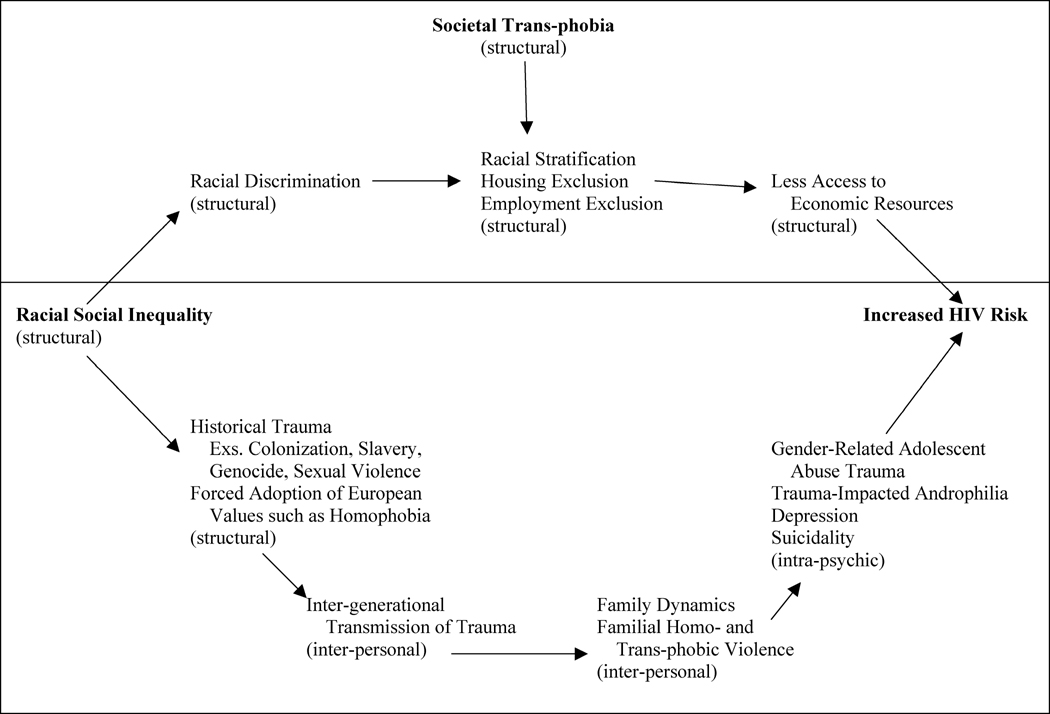

Through the integration of findings from previous and current research, we offer a more holistic model of HIV risk factors among transfeminine people of color that holds implications for informing harm-reduction public health strategies and approaches with this population. The top half of Figure 1 is based solely on our ethnographic findings and shows how sociostructural factors contribute to HIV risk. In this model, racial social inequality leads to racial discrimination, and racial discrimination compounded with societal transphobia may lead to life conditions such as housing and employment exclusion. Housing and economic exclusion translates to lower economic resources, which places considerable stress on transfeminine POC to participate in behaviors leading to increased HIV risk.

Figure 1.

Racial Social Inequality Holistic Model—Socio-structural, Inter-personal, and Intra-psychic Levels

The bottom half of Figure 1 integrates findings from both our ethnographic and quantitative studies and shows how HIV risk may be affected not only by structural factors, but also by interpersonal and intrapsychic factors. Racial inequality, historically, led to such phenomena as colonization, slavery, systematic sexual violence, and genocide, along with forced adoption of European values such as homo- and transphobia (Gilley, 2006; Roscoe, 1998). We conceptualize these historical traumas as inter-generationally transmissible across families and communities of color. One form of such transmission is the targeting of gender atypical and sexual minority children and adolescents for abuse/victimization within families of color. This victimization may then be internalized by gender atypical/sexual minority/transfeminine children of color and manifest as high levels of depression, suicidality, and a trauma-impacted androphilia that manifests, in part, as high-HIV risk behavior.

This model includes complex associations between sociostructural, interpersonal, and intrapsychic levels that may lead to high HIV risk. The importance of including all three levels in understanding HIV risk has been discussed in previous literature focusing on low-income cisgender women of color (Amaro, 1995; Bowleg et al., 2004). This more holistic conceptual model of HIV risk also addresses areas of foci emphasized as critically important in the IOM (2011) report: social ecology, minority stress, intersectionality, and lifecourse perspectives.7

Our holistic model also engages in what Roscoe (1998) describes as diachronic analysis, which is understanding phenomena as situated within particular historical moments. In applying this analysis to trans/gender-variant POC, we can begin to understand how their life experiences, such as gender-related childhood abuse, are situated within particular historical moments, including simultaneous and often interacting trajectories of colonization, post-colonization, and decolonization. This is in contrast to a synchronic analysis, which only examines contemporary phenomenon within the present time frame, and is not reflexive in situating the current phenomenon within its historical moment. An example of synchronic analysis is Koken et al. (2009) who discuss experiences of familial acceptance-rejection among transfeminine African Americans and Latinas. They conclude that many transfeminine POC experience rejection in families of color because these families are frequently rooted in religious traditions and have more “rigid ideas” about gender roles and the “immorality” of homosexuality/gender-variance (858).

Pursuing synchronic analyses, therefore, may thus lead to problematic pathologized characterizations (or even stereotyping) of families of color as inherently more rigid and homo-/transphobic than Euro-American families. Contextualizing families of color within a diachronic analysis, however, may reveal how historical trauma has affected (and continues to affect) families of color. Fully addressing historical-contemporary linkages and traumas may thus provide avenues for families of color to not only accept, but also perhaps even venerate their gender atypical/sexual minority children (as was often the case for societies and families in pre-colonial contexts throughout the Americas, Africa, and Asia) (Gilley, 2006; Henríquez, 2002; Johnson, 1997; Murray & Roscoe, 2001; Roscoe, 1998).

Conclusion

In conclusion, transfeminine POC are much more likely to be androphilic and at high HIV risk compared to Euro-American transfeminine people. Depression and suicidality rates are high among all transfeminine people, but for transfeminine POC, depression and suicidality rates during adolescence were strongly correlated with gender-related abuse perpetrated by family members. Depression may be one of several effects resulting from trauma experienced during adolescence. Gender-related adolescent abuse trauma may also manifest as “trauma-impacted androphilia,” as many transfeminine POC formed gender identities intertwined with androphilic sexual orientation during early adolescence. Trauma-impacted androphilia may also manifest as subsequent cycles of late adolescent and adult re-traumatization. Within the context of primary non-commercial sexual relationships with male partners, adult re-traumatization may lead to high-HIV risk behavior. A greater understanding of adolescent gender-related abuse and trauma-impacted androphilia may be essential for more efficacious HIV prevention, including the development of interventions that integrate sociostructural, interpersonal, and intrapsychic phenomena within a holistic conceptual model of HIV risk and harm reduction. As presented in the holistic model, health outcomes and HIV risk may be, at least in part, traceable back to origins of colonization, slavery, and genocide, and the inter-generational transmissions of (historical) trauma that have occurred from these origins through sociostructural, interpersonal, and intrapsychic trajectories. And these trajectories may also be occurring simultaneously, intersecting and compounding each other. It is thus intriguing to consider how applied HIV prevention may contribute towards both improved health and a process of decolonization for transfeminine POC, in which effective interventions that lead to positive health outcomes may be both informed by and indicative of processes of decolonization.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

These studies were funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA018080), and (R01-DA018080-Suppl) (Principal Investigator, Larry Nuttbrock, Ph.D.). The authors acknowledge Mona Rae Mason, Monica Macri, Jeffrey Becker, Hermenio Martinez, Lorena Borjas, Bali White, Tina, Sunny, and Sasha for data collection/analysis support, and graciously thank all our research participants.

Footnotes

“Cisgender men” refers to men who were born anatomically-male/assigned male at birth, self-identified and were perceived as boys, and who currently self-identify and are perceived as men. This distinguishes them from other groups who self-identify as men, such as transmen and certain intersex individuals.

Thus, the MSM category is comprised of two subgroups: one group is MSMW and the other group is sometimes referred to as MSMO (men who have sex with men only). The category MSM in and of itself does not solely imply men who only have sex with men, as it is sometimes misunderstood.

We utilize sex/gender here as they are understood within many indigenous sex/gender systems as compared to Euro-Western sex/gender systems. In many indigenous sex/gender systems, anatomy alone does not and cannot determine “sex,” “sex” is only fully manifested within sociality, and thus “sex” and “gender” are closely related. This is in contrast to Euro-Western systems where anatomy solely determines “sex,” and “sex” is always already anatomical whereas “gender” is manifested in sociality. See Hwahng, 2011, for further discussion.

All names are pseudonyms.

See Rostila, 2011, for discussion of thick trust vs. thin trust social networks and health.

Kulick (1998) discusses how the boyfriends of travestis are feminized through their economic dependence on travestis. Within U.S. poverty-class POC communities it has become normalized that cisgender women, not cisgender men, often support families (Ricketts, 1989). Thus, the economic dependence of male partners on transfeminine POC is not necessarily seen as an overtly feminized position and/or this feminization-through-economic-dependency contributes to the re-marginalization and re-subordination of poverty-class masculinity of color.

Although we acknowledge that a truly complex and inclusive model would also show interactions and associations between the two models, this type of highly-complex mathematical modeling is beyond the scope of this article.

Contributor Information

Sel J. Hwahng, Hunter College – City University of New York, 695 Park Avenue, Suite HW 1738, New York, New York, USA.

Larry Nuttbrock, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc., New York, New York, USA.

References

- Allen PG. The sacred hoop: Recovering the feminine in American Indian traditions. Boston, MA: Beacon; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H. Love, sex, and power: Considering women's realities in HIV prevention. The American Psychologist. 1995;50(6):437–447. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola SG, Neilands TB, Diaz R. Childhood sexual abuse and the sociocultural context of sexual risk among adult Latino gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(S2):S432–S438. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola SG, Neilands TB, Pollack LM, Paul J, Catania J. Childhood sexual experiences and adult health sequelae among gay and bisexual men: defining childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Sex Research. 2008;45(3):246–252. doi: 10.1080/00224490802204431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Jun H-J, Jackson B, Spiegelman D, Rich-Edwards J, Corliss HL, Wright RJ. Disparities in child abuse victimization in lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women in the Nurses' Health Study II. Journal of Women's Health. 2008;17(4):597–606. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Huang B, Fieland KC, Simoni JM, Walters KL. Culture, Trauma, and Wellness: A Comparison of Heterosexual and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Two-Spirit Native Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):287–301. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SK, Bhatia SC. Childhood and adolescent depression. American Family Physician. 2007;75(1):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting W, Miner M, Rosser S. Latino men’s sexual behavior with transgender persons. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36(6):778–786. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, Lucas KJ, Tschann JM. "The ball was always in his court": An exploratory analysis of relationship scripts, sexual scripts, and condom use among African American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28(1):70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL. African American resiliency: Examining racial socialization and social support as protective factors. Journal of Black Psychology. 2008;34(1):32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cohler BJ, Hammack PL. The psychological world of the gay teenager: Social change, narrative, and “normality”. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(11):1462–1482. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descamps MJ, Rothblum E, Bradford J, Ryan C. Mental health impact of child sexual abuse, rape, intimate partner violence, and hate crimes in the National Lesbian Health Care Survey. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2000;11(1):27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz R. Latino gay men and HIV: Culture, sexuality, and risk behavior. New York: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr . The life course and human development. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development. 5th ed. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 939–991. [Google Scholar]

- Gilley BJ. Becoming Two-Spirit: Gay identity and social acceptance in Indian country. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbach PM, Murphy R, Weiss RE, Hucks-Ortiz C, Shoptaw S. Bridging sexual boundaries: Men who have sex with men and women in a street-based sample in Los Angeles. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(Suppl 1):63–76. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. Pervasive effects of childhood sexual abuse in lesbians' recovery from alcohol problems. Substance Use & Misuse. 1996;31(2):225–239. doi: 10.3109/10826089609045810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez P, Henríquez P. Juchitán Queer Paradise. Mexico and Canada: Filmmakers Library; 2002. (Writer), (Director). [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D'Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hwahng SJ. The Western "lesbian" agenda and the appropriation of non-Western transmasculine people. In: Fisher J, editor. Gender and the science of difference: Cultural politics of contemporary science and medicine. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2011. pp. 164–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hwahng SJ, Allen B, Zadoretzky C, Barber H, McKnight C, Des Jarlais D. Resiliencies, vulnerabilities, and health disparities among low-income transgender people of Ccolor at New York City harm reduction programs. New York: Baron Edmond de Rothschild Chemical Dependency Institute, Beth Israel Medical Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hwahng SJ, Lin AJ. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning people. In: C T-S, Islam N, Rey M, editors. Asian American communities and health: Context, research, policy, and action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2009. pp. 226–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hwahng SJ, Nuttbrock L. Sex workers, fem queens, and cross-dressers: Differential marginalizations and HIV vulnerabilities among three ethnocultural male-to-female transgender communities in New York City. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. 2007;4(4):36–59. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2007.4.4.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwahng SJ, Nuttbrock L. Sexual health, happiness, and resiliency among transfeminine people of color in New York City; Paper presented at the Global Forum on MSM and HIV; Washington, D.C.. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. Beauty and power: Transgendering and cultural transformation in the southern Philippines. New York: Berg; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Koken JA, Bimbi DS, Parsons JT. Experiences of familial acceptance-rejection among transwomen of color. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(6):853–860. doi: 10.1037/a0017198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulick D. Travesti: Sex, gender and culture among Brazilian transgendered prostitutes. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lang S. Men as women, women as men: Changing gender in Native American cultures. Austin: University of Texas Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C, Yang C, Tobin K, Penniman T, Patterson J, Spikes P. Differences in the social networks of African American men who have sex with men only and those who have sex with men and women. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(10):e18–e23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Nestadt G, Cwi J, Heithoof K, Eaton WW. The Life Chart Interview: A standardized method to describe the course of psychopathology. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1994;Vol. 4:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Maulsby C, Sifakis F, German D, Flynn CP, Holtgrave D. Partner characteristics and undiagnosed HIV seropositivity among men who have sex with men only (MSMO) and men who have sex with men and women (MSMW) in Baltimore. Aids and Behavior. 2012;16(3):543–553. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez RM, Pinto R. “It's really a hard life”: Love, gender, and HIV risk among male to female transgender persons. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2007;9(3):233–245. doi: 10.1080/13691050601065909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S, Roscoe Will. Boy-wives and female husbands: Studies of African homosexualities. Palgrave Macmillan; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Operario D, Keatley JA, Han L, Soma T. HIV risk behaviors among male-to-female transgender persons of color in San Francisco. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;Vol. 94(7):1193–1199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Operario D, Keatley J, Villegas D. Social context of HIV risk behaviours among male-to-female transgenders of colour. AIDS Care. 2004;16(6):724–735. doi: 10.1080/09540120413331269567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Mason M, Hwahng S, Rosenblum A, Macri M, Becker J. A further assessment of Blanchard's Typology of Homosexual Versus Non-Homosexual or Autogynephilic Gender Dysphoria. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:247–257. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9579-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Hwahng S, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Mason M, Macri M, Becker J. Lifetime risk factors for HIV/STI infections among male-to-female transgender persons. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52(3):417–421. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6ed8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Hwahng S, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Mason M, Macri M, Becker J. Psychiatric impact of gender-related abuse across the life course of male-to-female transgender persons. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47(1):12–23. doi: 10.1080/00224490903062258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettiway LE. Honey, honey, Miss Thang: Being Black gay, and on the streets. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Prieur A. Mema's house, Mexico City: On transvestites, queens, and machos. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G. With respect to sex: Negotiating Hijra identity in South India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts E. The origin of Black female-headed families. Focus (special issue: defining and measuring the underclass) 1989;12(1):32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera FI. Contextualizing the experience of young Latino adults: Acculturation, social support and depression. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9:237–244. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera FI, Guarnaccia PJ, Mulvaney-Day N, Lin JY, Torres M, Alegria M. Family cohesion and its relationship to psychological distress among Latino groups. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30(3):357–378. doi: 10.1177/0739986308318713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe W. Changing ones: Third and fourth genders in Native North America. New York: St. Martin's Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rostila M. A resource-based theory of social capital for health research: Can it help us bridge the individual and collective facets of the concept? Social Theory & Health. 2011;9(2):109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Skay CL, Pettingell SL, Reis EA, Bearinger L, Resnick M, Combs L. Hazards of stigma: The sexual and physical abuse of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents in the United States and Canada. Child Welfare. 2006;85(2):195–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh LD, Operario D, Smith CD, Arnold E, Kegeles S. "We're going to have to cut loose some of our personal beliefs": Barriers and opportunities in providing HIV prevention to African American men who have sex with men and women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23(6):521–532. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.6.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sausa LA, Keatley J, Operario D. Perceived risks and benefits of sex work among transgender women of color in San Francisco. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36(6):768–777. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer S, Parks CA, McFarland W, Page-Shafer K, Delgado V, Ruiz JD, Klausner JD. Self-reported sexual identity, sexual behaviors and health risks: Examples from a population-based survey of young women. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2003;7(1):69–83. doi: 10.1300/J155v07n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Walters KL, Balsam KF, Meyers SB. Victimization, substance use, and HIV risk behaviors among gay/bisexual/Two-Spirit and heterosexual American Indian men in New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(12):2240–2245. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafoya T. Native gay and lesbian issues: The Two-Spirited. In: Greene B, editor. Ethnic and cultural diversity among lesbians and gay men. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon I. Killing us quietly: Native Americans and HIV/AIDS. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JK, Wyatt GE, Rivkin I, Ramamurthi HC, Li X, Liu H. Risk reduction for HIV-positive African American and Latino men with histories of childhood sexual abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(5):763–772. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9366-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]