Abstract

A copper-catalyzed three-component linchpin coupling method for the stereoselective union of readily available epoxides and allyl electrophiles is disclosed. Transformations employ [B(pin)]2-methane as a conjunctive reagent, resulting in the formation of two C–C bonds at a single carbon center bearing a C(sp3) organoboron functional group. Products are obtained in 42–99% yield, and up to >20:1 dr. The utility of the approach is highlighted by stereospecific transformations entailing allylation, tandem cross coupling, and application to the synthesis 1,3-polyol motifs.

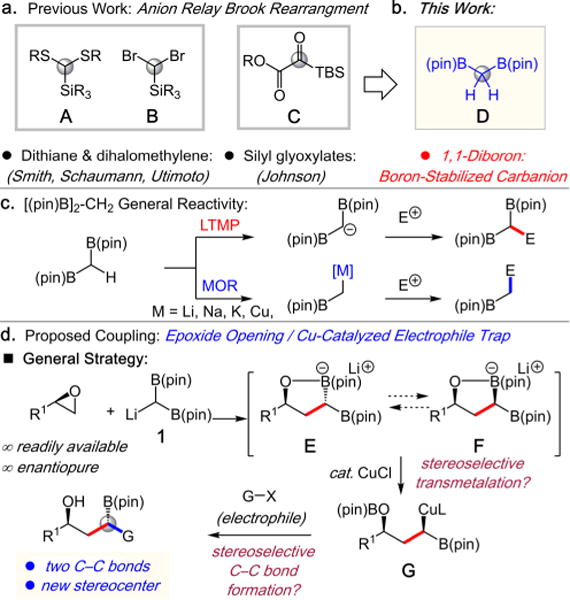

Chemical processes that stereoselectively construct multiple C–C bonds through single operations provide efficient strategies for the synthesis of important, complex bioactive molecules.1 In particular, substrate-controlled diastereoselective tandem processes have enjoyed significant attention as enabling strategies for rapid acyclic stereocontrol.2 Consequently, a number of tandem reactions that construct two C–C bonds in a single operation through a linchpin single-carbon center have been developed. Such examples include the dithiane anion relay chemistry developed by Smith in which a dithiane unit (e.g., A) serves as a double carbanion equivalent (Scheme 1a).3 In such transformations the dithiane carbon does not turn into a new C(sp3) stereocenter. This is in contrast to silyl glyoxylates (e.g., C) utilized by Johnson and co-workers in multicomponent electrophile/nucleophile couplings (Scheme 1a).4 Such reagents represent dual cation/anion synthons, wherein the acyl carbon becomes an C(sp3) stereocenter.

Scheme 1.

C1 Conjunctive Synthons that Form Two C–C Bonds at a Single Carbon Center per Chemical Step (2C)

1,1-Diborylalkanes (e.g., D) also represent potential versatile conjunctive reagents for stereoselective tandem linchpin couplings due to their versatile nature (Scheme 1c). Not only can both boron units be functionalized by deborylative processes,5 but due to the stabilizing effect of the two boron groups, the α-C–H bonds are rendered relatively acidic (pKa ∼ 31).6a,b In the presence of lithium amide bases, [B(pin)]2-C(H)Li (pin = pinacolato) can be generated, which reacts with electrophiles.6

Herein, we report a stereoselective one-pot three-component Cu-catalyzed coupling strategy that employs [B(pin)]2-methane as a conjunctive reagent, which enables the couplings of epoxides and allyl electrophiles. The general reaction design that affords 1,3-hydroxy-organoborons is illustrated in Scheme 1d. Ring-opening of readily available chiral epoxides with [B(pin)]2-C(H)Li (1) results in the formation of diastereomeric cyclic boronates E and F. Through substrate-controlled cyclic boronate formation or interconversion, subsequent stereospecific deborylative transmetalation generates organocopper G, which can engage with an electrophile.7 Examples of stereocontrolled C–C bond forming reactions that proceed via the intermediacy of a chelated boron-stabilized carbanion include the coupling of zincated-hydrazones with alkenylboronates,8 and substrate-controlled deborylative alkylations of tris-boronates.5b The overall transformation in Scheme 1d generates two C–C bonds and a new tertiary stereogenic center containing a versatile C(sp3)-B(pin) moiety.

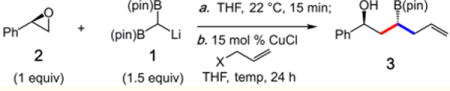

We initiated our studies with the coupling of (R)-styrene oxide (2) and allyl halide (Table 1). A key objective of the first phase centered on the ability to efficiently form two C–C bonds to [B(pin)]2-methane in a single operation. When (R)-styrene oxide (2) is treated with [B(pin)]2-C(H)Li 1 (1.5 equiv) in tetrahydrofuran (0 to 22 °C, 15 min), and the resulting mixture subjected to 15 mol % CuCl and allyl chloride at 22 °C, 52% conversion to 1,3-hydroxyboronate 3 is observed in 24 h (with a diastereomeric ratio, dr, of 3:1 anti/syn) (Table 1, entry 1).9,10 Reactions run at 45 and 60 °C proceeded with similar efficiency but in 2:1 dr (entries 2–3). Lower dr and diminished reactivity is furnished with phosphonate- and acetate-derived allyl electrophiles (entries 4–5). With allyl bromide the tandem reaction afforded 3 in 77% conversion and 8:1 dr (entry 6). Varying the copper salt resulted in either diminshed conversion and/or selectivity (entries 7–9). Lastly, reactions in the presence of phosphine ligands proceed with similar efficiency but lower dr (entries 10–11).

Table 1.

Cu-Catalyzed Three-Component Coupling Optimization

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| entry | X | Cu salt | ligand | Temp (°C) |

Conv (%)b |

drb |

| 1 | Cl | CuCl | – | 22 | 52 | 3:1 |

| 2 | Cl | CuCl | – | 45 | 52 | 2:1 |

| 3 | Cl | CuCl | – | 60 | 58 | 2:1 |

| 4 | OP(OEt)3 | CuCl | – | 60 | 45 | 1:1 |

| 5 | OAc | CuC | – | 60 | <2 | – |

| 6 | Br | CuCl | – | 60 | 77 | 8:1 |

| 7 | Br | CuOAc | – | 60 | 57 | 10:1 |

| 8 | Br | CuBr.dms | – | 60 | 55 | 8:1 |

| 9 | Br | Cul | – | 60 | 62 | 9:1 |

| 10 | Br | CuCl | rac-binap | 60 | 42 | 5:1 |

| 11 | Br | CuCl | PPh3 | 60 | 65 | 2:1 |

Reactions performed under N2 atm.

Conversion to 3; values determined by analysis of 400 or 600 MHz 1H NMR spectra of unpurified mixtures with DMF as internal standard.

A wide array of terminal and internal epoxides participate in the three-component coupling reaction. To facilitate isolation of the C(sp3) organoborons, the 1,3-hydroxyborons were protected as the TBS ethers. As illustrated in Scheme 2, aryl-substituted 1,3-hydroxyboronates (4–8) are generated in 45– 70% yield and in high dr (8:1 to >20:1 dr anti/syn). Reactions with terminal epoxides bearing sterically less demanding alkyl substituents furnished 9–12 efficiently (61–80% yield) albeit in up to 3:1 dr. With cyclohexene oxide, tandem C–C bond formation results in the stereoselective synthesis of 13 in 74% isolated yield bearing three stereogenic centers in >20:1 dr. Notably, trans-epoxides failed to undergo efficient ring-opening by 2; for example, trans-β-methylstyrene oxide results in <20% conversion to a complex mixture of regioisomers and diastereomers. Geminal disubstituted epoxides react with varying efficiency, as the reaction to form 14 proceeds in 58% yield and 5:1 dr, whereas β-pinene oxide derived 15 is furnished in 60% yield but 2:1 dr. Lastly, sterically congested limonene oxide provides 16 in 42% isolated yield as a single stereoisomer.

Scheme 2. Three-Component Couplings with Various Epoxidesa,b.

aReactions performed under N2 atm. bYield represents isolated yield of purified material and is an average of two experiments. cEpoxide opening: 22 °C for 24 h. dIsolated yield of diol after H2O2/NaOH oxidation. eEpoxide opening: 45 °C for 24 h.

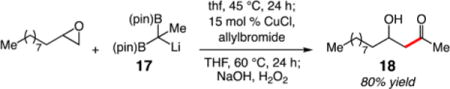

Increasing substitution on the 1,1-diboron was found to be tolerated in the epoxide-opening step; however, the corresponding cyclic borate failed to undergo transmetalation to Cu and allylic substitution. For example, reaction of 17 with 1-dodecene oxide efficiently generates ketone aldol product 18 in 80% yield after oxidation (eq 1).

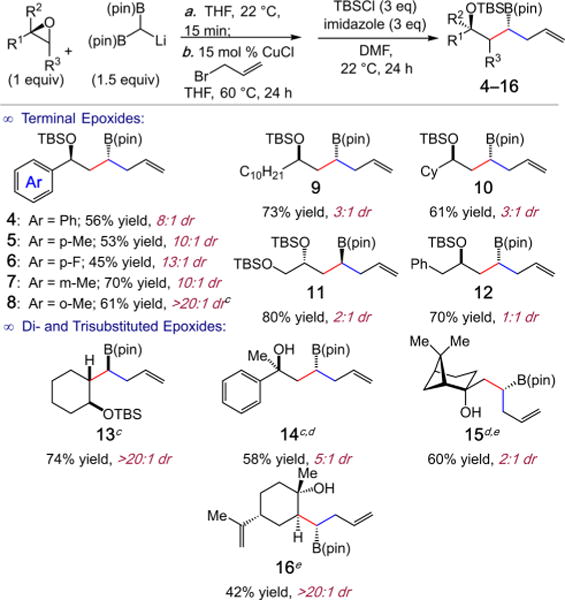

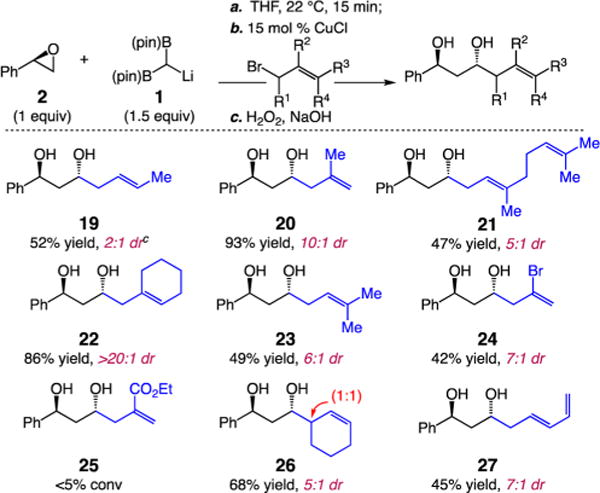

Followup studies illustrated in Scheme 3, demonstrate that a variety of substituted allyl electrophiles as well as dienyl bromides perform efficiently under standard conditions (15

|

(1) |

mol % CuCl, 1.0 equiv 2, 1.5 equiv 1), establishing two new C–C bonds and a sterocenter in good diastereoselectivity. Several features of these studies are notable: (1) Substituents at the 2-carbon of the allyl unit result in formation of the anti-product (e.g., 20, 22, and 24) in high selectivity 7:1 to >20:1 dr. (2) 3-Substituted allyl bromides afford the desired alkyl-B(pin) products with good regiocontrol but with diminution in dr (e.g., 19, 21, and 23). (3) Vinyl halides (24) but not esters (25) are tolerated under the reaction conditions. (4) Reaction with (E)-5-bromopenta-1,3-diene affords SN2 substitution product 27 (45% yield, 7:1 dr). (5) Notably, reaction with racemic 3-bromocyclohex-1-ene furnishes 26 with good diastereocontrol for the anti-1,3-hydroxy-B(pin); however, the additional stereocenter is formed in 1:1 dr. The data above suggest that higher diastereoselectivity is associated with bromide electrophiles that can react via an SN2′ pathway.

Scheme 3. Tandem Coupling Electrophile Scopea,b.

a,bSee Scheme 2. c3:1 SN2:SN2′.

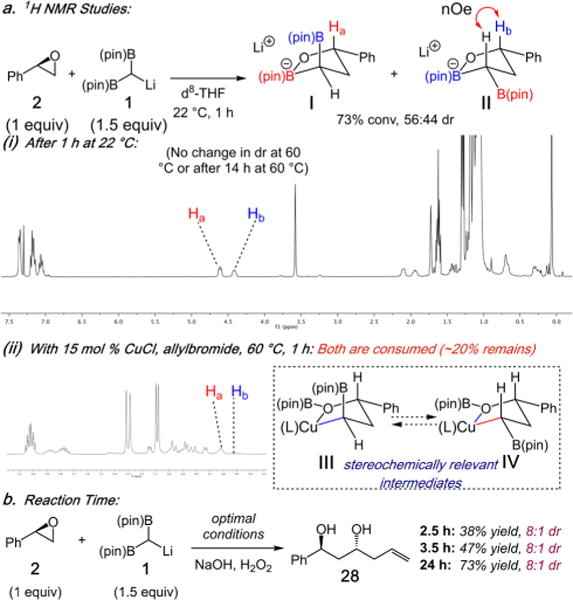

Consistent with the proposed pathway in Scheme 1c, we set out to identify the cyclic boronates E and F, and provide support for a model to explain the reaction diastereoselectivity. As shown in Scheme 4a(i), monitoring the ring-opening of 2 (1 equiv) with 1 (1.5 equiv) by 1H NMR in d8-THF at 22 °C results in 73% conversion to diastereomers I and II in 56:44 dr. Each stereoisomer could be assigned through the absence of (e.g., I) or presence of (e.g., II) an NOE diaxial interaction between the carbinol methine (Ha and Hb) and the [(pin)B]2C–H methane. 1H NMR of the mixture of I and II at 60 °C, or after heating at 60 °C for 14 h, does not result in any changes in the diastereoisomer ratio. Treatment of the solution of I and II with 15 mol % CuCl and allyl bromide (Scheme 4a(ii)) results in consumption of both diastereoisomers at similar rates, and after 1 h ∼20% I still remains. Further time points (Scheme 4b) demonstrate the dr of 28 (8:1) is independent of the time. This data indicates that although the cyclic boronates are formed in low dr, they both react at similar rates, and thus the high anti-selectivity must arise from the kinetic selectivity of Cu-alkyl species III and IV generated via transmetalation. However, it is not known whether III and IV are formed in high dr or if III and IV interconvert rapidly (Curtin–Hammett) prior to C–C bond formation.

Scheme 4. Mechanistic Studiesa.

aSee SI for details.

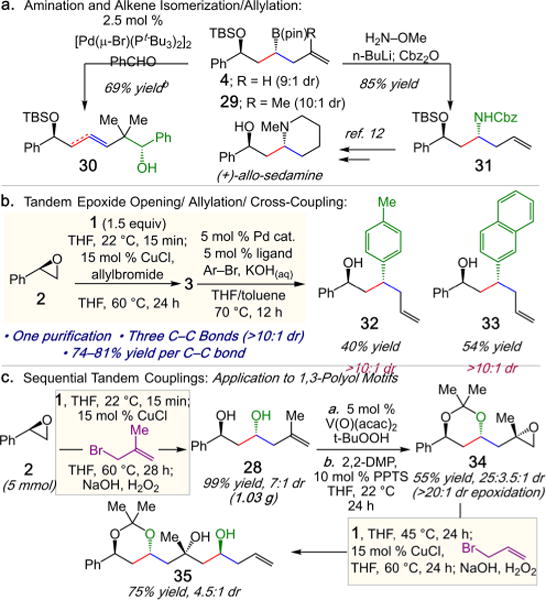

The 1,3-hydroxy-homoallylboronates accessible through the linchpin three-component coupling method are amenable to a wide range of useful functionalizations (Scheme 5a). For example, TBS protected homoallyl boronates 4 can be efficiently converted to the corresponding 1,3-amino alcohol 31 in 85% yield,11 a key intermediate in the stereoselective synthesis of (+)-allo-sedamine.12 Homoallyl-B(pin) 29 in the presence of 2.5 mol % [Pd(μ-Br)(Pt-Bu3)2]2 and benzaldehyde results in situ isomerization and diastereoselective allyl addition to furnish homoallylic alcohol 30 in 69% yield.13 In addition, the three-component coupling protocol can also be extended to include sequential stereoretentive cross coupling of the crude 1,3-hydroxy-B(pin) products (Scheme 5b).14 For example, treatment of crude 3 with 5 mol % Pd(dba)2, 5 mol % RuPhos, and an aryl bromide in KOH(aq) at 70 °C for 12 h delivers 32 and 33 in 40% and 54% isolated yield, respectively, and >10:1 dr. Furthermore, the utility of the diborylmethane linchpin coupling protocol is highlighted in the concise approach to 1,3-polyol motifs through an iterative sequence (Scheme 5c).15 Beginning with styrene oxide 2 (5 mmol scale) under standard conditions with 2-methylallyl bromide, anti-1,3-diol 28 (1.03 g) is isolated in 99% yield and 7:1 dr.16 Subsequent hydroxyl-directed epoxidation (5 mol % V(O)(acac)2, t-BuOOH) of the terminal alkene,17 and ketal formation furnishes 34 in 55% yield and 25:3.5:1 dr (2 steps). Subjecting 34 to standard coupling conditions in Scheme 2 with allyl bromide delivers diol 35 in 75% yield and 4.5:1 dr (equivalent to a ketone allylation). The sequential four-step sequence enables the rapid stereoselective assembly of four C–C bonds and three strereocenters (41% overall from 2).

Scheme 5. Utility of 1,3-Hydroxy Homoallyl Boronatesa.

aSee SI for details. b1H NMR yield (4:1 E-alkene isomers).

To conclude, we have introduced a stereoselective linchpin coupling method that utilizes [B(pin)]2-methane as a C1 conjunctive reagent for the linking of epoxide and allyl electrophiles. Reactions proceed efficiently, delivering products with good levels of diastereoselectivity that are amenable to accessing a range of useful organic molecules. Further stereoselective reactions of cyclic borates are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM116987, 3R01GM116987-01S1) and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. AllyChem is acknowledged for donations of B2(pin)2. We are grateful to Amber Charitos for experimental assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b09309.

Experimental procedures and spectral and analytical data for all products (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.For examples of recent reviews, see:; (a) Ho TL. Tandem Organic Reactions. Wiley; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]; (b) Parsons PJ, Penkett CS, Shell AJ. Chem Rev. 1996;96:195–206. doi: 10.1021/cr950023+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tietze LF. Chem Rev. 1996;96:115–136. doi: 10.1021/cr950027e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nicolaou KC, Edmonds DJ, Bulger PG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:7134–7186. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ramón DJ, Yus M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:1602–1634. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ruijter E, Scheffelaar R, Orru RVA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:6234–6246. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Marek I, Minko Y, Pasco M, Mejuch T, Gilboa N, Chechik H, Das JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2682–2694. doi: 10.1021/ja410424g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eppe G, Didier D, Marek I. Chem Rev. 2015;115:9175–9206. doi: 10.1021/cr500715t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For dithianes, see:; (a) Bräuer N, Dreeßen S, Schaumann E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2921–2924. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fischer MR, Kirschning A, Michel T, Schaumann E. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1994;33:217–218. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith AB, III, Boldi AM. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6925–6926. [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith AB, III, Pitram SM. Org Lett. 1999;1:2001–2004. doi: 10.1021/ol991166b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Smith AB, III, Pitram SM, Boldi AM, Gaunt MJ, Sfouggatakis C, Moser WH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14435. doi: 10.1021/ja0376238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Smith AB, III, Kim D-S. Org Lett. 2004;6:1493. doi: 10.1021/ol049601b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Smith AB, III, Tong R. Org Lett. 2010;12:1260. doi: 10.1021/ol100130x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Smith AB, III, Han H, Kim W-S. Org Lett. 2011;13:3328. doi: 10.1021/ol2010598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Melillo B, Smith AB., III Org Lett. 2013;15:2282. doi: 10.1021/ol400857k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For dihalomethanes, see:; (j) Shinokubo H, Miura K, Oshima K, Utimoto K. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:503–514. [Google Scholar]; (k) Shinokubo H, Miura K, Oshima K, Utimoto K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:1951–1954. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Nicewicz DA, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6170. doi: 10.1021/ja043884l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicewicz DA, Satterfield AD, Schmitt DC, Johnson JS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17281–17283. doi: 10.1021/ja808347q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schmitt DC, Johnson JS. Org Lett. 2010;12:944. doi: 10.1021/ol9029353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Schmitt DC, Lam L, Johnson JS. Org Lett. 2011;13:5136. doi: 10.1021/ol202002r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Hong K, Liu X, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10581–10584. doi: 10.1021/ja505455z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Coombs JR, Zhang L, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16140–16143. doi: 10.1021/ja510081r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Joannou MV, Moyer BS, Meek SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:6176–6179. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Joannou MV, Moyer BS, Goldfogel MJ, Meek SJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2015;54:14141–14145. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Shi Y, Hoveyda AH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:3455–3458. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Murray SA, Green JC, Tailor SB, Meek SJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:9065–9069. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Park J, Lee Y, Kim J, Cho SH. Org Lett. 2016;18:1210–1213. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kim J, Park S, Park J, Cho SH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:1498–1501. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Ebrahim-Alkhalil A, Zhang ZQ, Gong TJ, Su W, Lu XY, Xiao B, Fu Y. Chem Commun. 2016;52:4891–4893. doi: 10.1039/c5cc09817c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Kim J, Ko K, Cho SH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2017;56:11584–11588. doi: 10.1002/anie.201705829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For an example of deborylative 1,4-addition of 1,1,1-tris-boronates, see:; (k) Palmer WN, Zarate C, Chirik PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2589–2592. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Matteson DS, Moody RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:3196–3197. [Google Scholar]; (b) Matteson DS, Moody RJ. Organometallics. 1982;1:20–28. [Google Scholar]; (c) Endo K, Hirokami M, Shibata T. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3469–3472. doi: 10.1021/jo1003407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Coombs JR, Zhang L, Morken JP. Org Lett. 2015;17:1708–1711. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Jo W, Kim J, Choi S, Cho SH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:9690–9694. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For examples of generation and trapping of diastereomeric Cu(I) alkyl species, see:; (a) Dieter RK, Watson RT, Goswami R. Org Lett. 2004;6:253–256. doi: 10.1021/ol036237s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dieter RK, Oba G, Chandupatla KR, Topping CM, Lu K, Watson RT. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3076–3086. doi: 10.1021/jo035845i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatakeyama T, Nakamura M, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15688–15701. doi: 10.1021/ja806258v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.15 mol % CuCl was found to afford slightly improved yields vs 10 mol %. This is likely due to reaction mixture turning heterogeneous as the reaction proceeds.

- 10.SFC analysis of 3 compared to 1 indicates there is no loss of enantiopurity during the epoxide-opening/Cu-catalyzed allylation sequence.

- 11.Mlynarski SN, Karns AS, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16449–16451. doi: 10.1021/ja305448w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spangenberg T, Airiau E, Donnard M, Billet M, Mann A, Thuong M. Synlett. 2008;2008:2859–2863. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miura T, Nakahashi J, Murakami M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2017;56:6989–6993. doi: 10.1002/anie.201702611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaisdell TP, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8712–8715. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rychnovsky SD. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2021–2040. [Google Scholar]

- 16.An improvement in coupling efficiency was observed when reaction run on increased scale (e.g., 5 mmol and 99% yield).

- 17.Hoveyda AH, Evans DA, Fu GC. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1307–1370. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.