Abstract

Objective

This study evaluates the impact of an integrated Behavioral Health Home (BHH) pilot for adults with psychotic and bipolar disorders.

Methods

Quasi-experimental methods were used to compare outcomes pre- (September 2014 to August 2015) and post-intervention (September 2015 to August 2016) among ambulatory BHH participants and non-participants. Electronic health records of 424 BHH participants (369 with a psychotic disorder; 55 with bipolar disorder) were compared with 1521 individuals not in the BHH from an urban, safety-net health system. Groups were propensity score-weighted by sex, age, race/ethnicity, language, 2010 Census block group demographics, Medicare and Medicaid enrollment, and diabetes diagnosis.

Results

BHH participants had fewer total psychiatric inpatient (IP) visits and fewer total ED visits compared to non-BHH patients, which was predominantly driven by the smaller number of visits among BHH participants with ≥1 visit. There were no differences in medical hospitalizations. While BHH participants were more likely to receive HbA1c screening, there were no differences in lipid monitoring. Regarding secondary outcomes, there were no significant differences in changes in metabolic monitoring parameters among patients with diabetes.

Conclusions

Participation in a pilot ambulatory BHH program was associated with significant reductions in ED visits and psychiatric hospitalizations, and increased HbA1c monitoring, among patients with psychotic and bipolar disorders. Longer-term evaluation is needed to assess impact on care processes and population health outcomes. This evaluation builds on prior research by specifying intervention details and the clinical target population, strengthening the evidence base for care integration to support further program dissemination.

Introduction

Millions of US adults experience schizophrenia-spectrum or bipolar disorder during their lifetime, with estimated prevalence of 1.2 percent1 and 2.1 percent,2 respectively. Individuals with serious mental illness in the US die 20 to 30 years earlier than the general population,3–5 primarily due to medical conditions like COPD, pneumonia/influenza, lung cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.6,7 Nearly 41% of persons with serious mental illness report unmet physical health needs8 despite high rates of chronic conditions.9 These physical comorbidities emerge due to multiple factors, including unhealthy behaviors (e.g. tobacco use, physical inactivity, poor diet), iatrogenic effects of antipsychotic medications, and social adversity.10–12

Inadequate primary care utilization may drive poor health outcomes for those with serious mental illness. US adults with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are, respectively, 45% and 26% less likely than those without mental disorders to have a primary care physician.13 When people with serious mental illnesses do access primary care, they frequently receive lower-quality care than the general population.14–18 Interventions that improve healthcare access for patients with milder mental health needs19 by incorporating behavioral health services into primary care largely do not reach people with serious mental illness, who often view mental health specialists – not primary care providers (PCPs) – as their usual source of care.20–22

Approaches to integrating medical services into mental health practices23,24 include the "Behavioral Health Home" (BHH) model, which provides enhanced access to medical services, care coordination, care transition support, and health promotion.12,25,26 Yet the effectiveness of BHH models remains in question. Studies to date have applied the BHH in unique settings such as the Veteran’s Health Administration,20,27 examined varied BHH intervention components,23 included diagnostically heterogeneous populations,23,28 or focused primarily on physical health outcomes.28 Even evaluations that specified intervention components have yielded mixed findings, such as improvements in quality measures but not clinical outcomes.29 Recent work comparing two integrated care approaches30 identified that programs with greater integration were associated with improved self-reported health, increased screening for chronic conditions, and reduced hypertension, but increased rates of diabetes/prediabetes.

The present study extends existing literature by evaluating a clearly-defined BHH program, implemented in a safety net institution, for adults with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders or bipolar disorder. Because the program targeted patients’ quality of care and stability in community-based settings, we hypothesized that the BHH would reduce Emergency Department (ED) visits, reduce medical and psychiatric inpatient admissions, and increase preventive health screenings. Since the motivation to integrate care derives from a belief that mental and physical health are inextricably linked, we hypothesized that the BHH would improve both medical and psychiatric service use outcomes. We therefore also evaluated the impact of the BHH on secondary metabolic outcomes of HbA1c, glucose, and LDL for patients with diabetes.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

Data were collected from electronic health records (EHR) in an urban safety-net academic medical system that provides a full continuum of care to over 140,000 patients annually at multiple hospitals and community clinics. The study included individuals receiving treatment September 2014 - August 2016 for a primary psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or other psychotic disorder; n=1331) or bipolar disorder (if treatment included antipsychotic medication; n=614) with ≥1 mental or physical health care visit pre- and post-intervention. Those with bipolar disorder required an antipsychotic prescription to enroll in the BHH to ensure the program served those with greatest psychiatric need and medical risk.

The BHH program was established at the system’s largest outpatient community-based mental health clinic. On September 1, 2015, patients meeting diagnostic criteria and receiving care at either this mental health clinic or a nearby primary care practice were automatically assigned to the BHH. Subsequent BHH referrals were accepted from throughout the health system based on standard criteria (psychiatric diagnosis, medical risk/comorbidity, care coordination needs). These criteria were communicated to providers and administrators via mailings and site visits. Eligible referred patients were offered an intake appointment and enrolled voluntarily. EHR use and communication with existing providers ensured non-duplication of services.

Non-BHH patients had the same diagnoses but received outpatient mental health and medical care in other clinics within the health system. Of 1865 non-BHH patients originally identified, 344 were removed from analysis due to no post-intervention contact within the health system to avoid misclassifying those potentially utilizing care at other healthcare systems as non-users. Remaining non-BHH group participants (n=1,521; 962 with psychotic disorder and 559 with bipolar disorder) were weighted to have the same baseline characteristics as the original pre-intervention non-BHH population. This additional weighting step for the non-BHH group approximates an intent-to-treat analysis. This weighting to account for missingness was not necessary for BHH patients who were fully observed pre- and post-intervention within the health system.

Outcome Variables

Primary outcomes chosen a priori are any use of psychiatric or medical inpatient hospitalizations or ED visits, total number of visits for these services, number of visits conditional on ≥1+ visits (excluding zeros), and screening rates for cardiometabolic health (LDL, HbA1c, glucose). As secondary outcomes, laboratory values for these metabolic tests were assessed among diabetic patients.

Description of the Intervention

Usual care included an individualized combination of psychopharmacology, individual/group psychotherapy, sporadic use of primary care and/or specialty services, and little-to-no EHR-based tracking of healthcare utilization. The Massachusetts Medicaid Section 1115 Waiver purposefully included incentives for establishing the BHH as a safety-net hospital innovation. Clinical services were billed for reimbursement, primarily from Medicare/Medicaid in this population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of BHH Intervention and non-BHH Patients Before Propensity Score Weighting

| Variable | Non-BHH Patients n=1521 |

All BHH Patients n=424 |

p-value | *<.10 **<.05 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 51.35 | 46.70 | .090 | * |

| Age | 50.19 | 48.41 | .044 | ** |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White Non-Hispanic | 59.11 | 64.15 | .061 | * |

| Black | 18.41 | 22.17 | .082 | * |

| Hispanic | 8.42 | 2.12 | .000 | ** |

| Asian | 1.97 | 2.12 | .845 | |

| Non-English Speaker | 20.84 | 10.61 | <.001 | ** |

| Medicare | 48.72 | 56.60 | .004 | ** |

| Medicaid | 33.00 | 32.78 | .932 | |

| Private Insurance | 70.61 | 70.75 | .954 | |

| Uninsured | 1.12 | .71 | .459 | |

| % Female Head of Household (CBG) | 21.36 | 22.46 | .003 | ** |

| % Foreign Born (CBG) | 29.76 | 28.90 | .272 | |

| % Living <FPL (CBG) | 11.27 | 12.27 | .187 | |

| % Less than High School Grad (CBG) | 13.96 | 11.82 | <.001 | ** |

| Diabetes | 15.78 | 10.14 | .004 | ** |

| Bipolar Disorder | 36.75 | 12.97 | <.001 | ** |

| Hypertension | 33.00 | 25.94 | .006 | ** |

| LDL Level (n=635 control, n=202 BHH) | 106.33 | 113.86 | .010 | ** |

| HbA1c% (n=639 control, n=209 BHH) | 6.27 | 5.91 | .00 | ** |

| Fasting Glucose | 121.20 | 113.21 | .062 | * |

| Current Smoker | 30.97 | 32.08 | .663 | |

| Pre-Period Primary Care Visits | 3.86 | 4.20 | 0.23 | |

| Pre Period ED Use (%) | 40.43 | 38.21 | .408 | |

| Pre Period Psychiatric Hospitalization (%) | 8.15 | 12.03 | .014 | ** |

| Pre Period Medical Hospitalizations (%) | 20.78 | 17.45 | .131 | |

| Pre Period Glucose Screen (%) | 69.17 | 64.62 | .076 | * |

| Pre Period HbA1c Screen (%) | 42.01 | 49.29 | .008 | ** |

| Pre Period LDL screen (%) | 41.75 | 47.64 | .030 | ** |

Note. BHH = Behavioral Health Home Program; CBG = Census Block Group; LDL = Low Density Lipoprotein; ED = Emergency Department; HbA1c = Hemoglobin A1c

The BHH implemented four key medical and psychiatric service enhancements. First, services expanded to include on-site medical care, health promotion (e.g. smoking cessation group, healthy lifestyle groups, health coaching), support for care coordination and transitions, and peer-to-peer engagement opportunities (e.g. drop-in milieu space, social gatherings, health education workshops). Second, EHR functionality was enhanced to include: provider alerts for patient transitions through ED or inpatient units, a registry for monitoring individuals’ health status and service delivery, acute care discharge report facilitating follow-up care, and a performance measurement dashboard. Third, three new positions, a medical nurse practitioner, care manager, and program manager, were established to supplement the existing team of 2.0 FTE psychiatrists, 1.75 FTE masters-level therapists, and trainees. Fourth, the BHH shifted clinical practice toward fully-integrated, team-based care, group therapy modalities, health promotion, chronic disease screening/monitoring, social inclusion, and population management. Reducing social isolation was emphasized because of the endemic isolation in this population and evidence about the role of social networks in facilitating behavior change.31

Once enrolled, BHH participants were encouraged to utilize available services that aligned with personal goals. Therefore, some frequently accessed integrated medical care and health promotion activities, while others benefitted primarily from population management, health monitoring, and care coordination improvements. Some utilized the BHH nurse practitioner as their main source of medical care, though many maintained pre-existing relationships with their PCPs.

Statistical Methods

Comparison of Treatment and non-BHH Groups at Baseline

Baseline characteristics of BHH participants and weighted non-BHH participants were described for the total population (and for subgroups by disorder) using chi-squared statistics (for binary variables) and two-sample t-tests (for continuous variables).

Propensity Score Weighted Regression Analysis of Treatment Effect

We used propensity score weighted generalized estimating equations to estimate the BHH treatment effect. Propensity score methods balance the treatment and control groups on pre-period characteristics that influence selection into treatment, so that one can more confidently attribute observed outcomes to the BHH.32 Because the propensity score is a scalar representing a prediction from multiple variables, propensity score weighting is not expected to produce a perfect match between treatment and control groups across all covariates simultaneously. In the control group, propensity score weights were multiplied by weights that account for ‘missing’ status as described above. The overall propensity score was then estimated as the probability of assignment to treatment (BHH) conditional on observed covariates measured in the 1-year period prior to the start of the BHH.

Propensity scores were estimated using the following patient baseline covariates associated with health service utilization that may have influenced selection into the treatment group (BHH): sex; age; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic black, Asian, Hispanic); non-native English speaker; Medicare enrollment; Medicaid enrollment; diagnosis of diabetes or bipolar disorder. 2010 U.S. Census-based demographic measures linked to patients' addresses were also entered into the propensity score (percent foreign-born, percent living below federal poverty level, percent with female head of household, percent less than high school graduate). Conditional on the propensity score, the distributions of observed covariates approximate the randomization of individuals,33 thus balancing treatment and non-BHH groups on baseline demographics, and neighborhood socioeconomic status. In a sensitivity analysis, we included presence of outpatient primary care visits in the propensity score weighting.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were estimated using a population averaged panel data model (each patient contributed both a pre- and post-intervention data record) and exchangeable within-group correlation structure to account for within-patient variation (robust standard errors). GEEs were weighted based on the propensity score described above, and predictive margins were compared in the pre- and post-period for the treatment and non-BHH groups. For each outcome of interest, the appropriate link function was specified (logit link for binary outcomes for any inpatient physical/mental health care, any ED visit, any metabolic screen; log link, gamma family of variance for number of visits and lab results). Weighted analyses were performed using svy commands in Stata 14.34

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Prior to propensity score weighting, BHH patients had significantly different pre-period demographic and service use characteristics (Appendix Table 1). BHH patients were slightly younger (48.4 vs. 50.2 years old). BHH patients were less likely to be Hispanic (2.1% vs. 8.4%) or non-English speakers (10.6% vs. 20.8%). Their census block groups (CBGs) had lower percent of high school graduates, and higher percent of females as heads of households. They were less likely to have diabetes (10.1% vs. 15.8%), hypertension (25.9% vs. 33%), or bipolar disorder (13.0% vs. 36.8%). Among the subset of BHH and non-BHH patients with lab results, BHH patients had lower HbA1c values (5.9 vs. 6.3) but higher LDL levels (113.9 vs. 106.3), and more often received HbA1c screenings in the pre-period (49.3% vs. 42.0%). BHH patients were more often Medicare beneficiaries (56.6% vs. 48.7%). Rates of ED use and medical hospitalizations were similar for both groups, but BHH patients had slightly higher rates of pre-period psychiatric hospitalizations (12.0% vs. 8.2%).

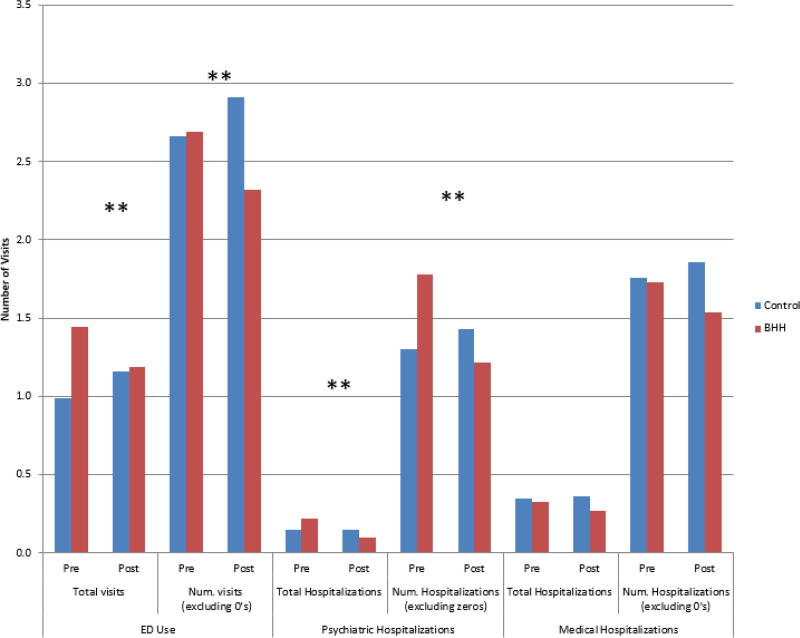

Quasi-Experimental Results

Propensity score weighting successfully balanced BHH and non-BHH participants on selected pre-period time-invariant characteristics (See Figure 1). Test statistics confirmed the weighted sample bias was within permissible range, and mean bias was reduced from 15.4 to 5.6.

Figure 1. Covariate Balance After Propensity Score Weighting.

Propensity scores included the following covariates: sex; age; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic black, Asian, Hispanic); non-native English speaker (ESL); Medicare enrollment; Medicaid enrollment; diagnosis of diabetes or bipolar disorder; area-level variables (percent foreign-born, percent living below federal poverty level (FPL), percent with female head of household (HH), percent less than high school (<HS) graduate).

After 12 months, BHH patients had significant differences from non-BHH patients on several measures of health care service utilization (Table 2) and HbA1c testing, and a non-significant trend toward improved LDL testing (Table 3).

Table 2.

Pre-Post Differences for Service Utilization for BHH and non-BHH Patients with Propensity Score Weighting

| Contrast (BHHPost − ControlPost) − (BHHPre − ControlPre) |

Delta SE | p-value | *<.10; **<.05 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service Utilization | ||||

|

| ||||

| % Patients with Any ED Use | .011 | .033 | .728 | |

|

| ||||

| Total ED visits | −.428 | .174 | .014 | ** |

|

| ||||

| Num. ED visits (excluding zeros) | −.618 | .221 | .005 | ** |

|

| ||||

| % Patients with any psychiatric hospitalizations | −.030 | .021 | .148 | |

|

| ||||

| Total psychiatric hospitalizations | −.125 | .040 | .002 | ** |

|

| ||||

| Num. psychiatric hospitalizations (excluding zeros) | −.685 | .210 | .001 | ** |

|

| ||||

| % Patients with any medical hospitalizations | −.005 | .025 | .826 | |

| Total medical hospitalizations | −.067 | .051 | .182 | |

| Num. medical hospitalizations (excluding zeros) | −.292 | .178 | .101 | |

Note. BHH = Behavioral Health Home Program; PS = propensity score.

Estimated using GEE models (Stata xtgee and margins commands; logit link for binary outcomes and log link and gamma family variance for continuous outcome measures). Models were adjusted for propensity score weights using the Stata svy command. Propensity scores included the following covariates: sex; age; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic black, Asian, Hispanic); non-native English speaker; Medicare enrollment; Medicaid enrollment; diagnosis of diabetes or bipolar disorder; area-level variables (percent foreign-born, percent living below federal poverty level (FPL), percent with female head of household, percent less than high school graduate).

Table 3.

Pre-Post Differences for BHH and non-BHH Patients with Propensity Score Weighting

| Delta SE | Control | BHH | Difference | (contrast) | Delta SE | p- value |

*<.10; **<0.05 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screenings | ||||||||

| LDL Test | Pre | .404 | .476 | .072 | ||||

| Post | .441 | .587 | .146 | .074 | .038 | .052 | * | |

| Hemoglobin A1c Test | Pre | .400 | .493 | .093 | ||||

| Post | .461 | .636 | .175 | .082 | .037 | .026 | ** | |

| Glucose Test | Pre | .676 | .644 | −.033 | ||||

| Post | .695 | .679 | −.016 | .017 | .034 | .624 | ||

| Either HbA1c or Glucose Test | Pre | .746 | .767 | .021 | ||||

| Post | .746 | .818 | .073 | .052 | .031 | .093 | * | |

| Health measures and lab results | ||||||||

| LDL levels | Pre | 106.231 | 113.786 | 7.555 | ||||

| Post | 108.178 | 111.444 | 3.267 | −4.289 | 3.286 | .192 | ||

| Hemoglobin A1c levels | Pre | 6.066 | 5.854 | −.212 | ||||

| Post | 5.978 | 5.804 | −.175 | .037 | .078 | .633 | ||

| Glucose levels | Pre | 117.038 | 111.795 | −5.242 | ||||

| Post | 113.189 | 111.123 | −2.066 | 3.176 | 2.905 | .274 |

Note. BHH = Behavioral Health Home Program; PS = propensity score; LDL = Low Density Lipoprotein; HbA1c = Hemoglobin A1c

Estimated using GEE models (Stata xtgee and margins commands; logit link for binary outcomes and log link and gamma family variance for continuous outcome measures). Models were adjusted for propensity score weights using the Stata svy command. Propensity scores included the following covariates: sex; age; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic black, Asian, Hispanic); non-native English speaker (ESL); Medicare enrollment; Medicaid enrollment; diagnosis of diabetes or bipolar disorder;, area-level variables (percent foreign-born, percent living below federal poverty level (FPL), percent with female head of household (HH), percent less than high school (<HS) graduate).

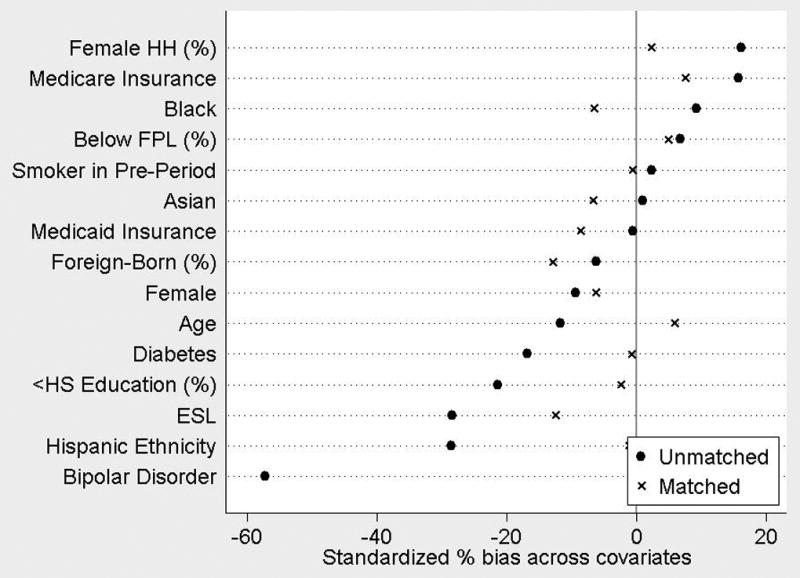

There was no significant difference in the pre-post change in any ED visit between the BHH and propensity-weighted non-BHH group (Table 2). However, the total number of ED visits per capita decreased significantly among BHH participants (1.45 to 1.19 visits) compared to non-participants, whose total ED visits rose from 0.99 to 1.16 (p=.014 for contrast). Significant differences for total ED visits were driven by the difference among patients with ≥1 visit (number of visits excluding zeros), declining from 2.69 to 2.32 visits in the BHH group (p=.005 for contrast to the non-BHH group). Figure 2 illustrates actual service use rates by group and time.

Figure 2. Number of Visits Pre and Post BHH Intervention for BHH and Control Patients with Propsensity Score Weighting.

Total psychiatric hospitalizations declined for BHH participants (.22 to .10) compared to stable rates for non-BHH participants (.145 to .147; contrast p-value .002). Similar to the reduction in ED visits, the overall number of BHH participants experiencing psychiatric hospitalizations did not significantly change (contrast p-value .148), but number of hospitalizations among those with ≥1 decreased significantly (1.78 to 1.22 for BHH and 1.31 to 1.43 for non-BHH; contrast p-value .001). Neither rate nor number of medical hospitalizations (total or among those with ≥1 hospitalization) differed significantly in pre and post period across treatment and control groups.

BHH patients’ HbA1c screening rates increased (.49 to .64) relative to non-BHH patients (.40 to .46; contrast p-value .026, Table 3). Though not significant, LDL testing rates moved in the same direction (contrast p=.052). Improvements in metabolic laboratory values for BHH patients with diabetes were not significantly greater than non-BHH patients with diabetes in the control group (Appendix Table 2).

In an analysis by diagnosis, we found reduced ED visits and psychiatric hospitalizations, and increased HbA1c testing for those with schizophrenia, echoing results for the total BHH population, but no significant results for bipolar patients (Appendix Table 3). In sensitivity analyses incorporating prior year primary care visits into the propensity score weighting, we observed no difference in the patterns and significance of our results (Appendix Table 4).

Discussion

Findings from this safety net BHH program for adults with serious mental illness reduced rates of psychiatric hospitalization and ED utilization, and increased HbA1c screenings for BHH patients. The BHH had no effect on rates of medical hospitalization or LDL screening, or values of metabolic parameters for diabetic patients over the 12-month study period.

This evaluation builds on earlier studies of integrated care for people with serious mental illness in important ways. First, we define the elements of the BHH intervention. Such specificity is critical to enabling replication of findings and dissemination of complex interventions to diverse settings. Second, since BHH services will likely have more impact for those with greater illness severity, this study describes participants’ diagnoses in a BHH intervention designed for patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders that are at greatest medical risk. Participation in BHH was associated with improvements for the population with schizophrenia but not among patients with bipolar disorder, though sample sizes of patients with bipolar disorder were relatively small. Third, we measured medical and psychiatric hospitalizations separately, enabling more precise understanding of the intervention’s impact on acute care utilization. Fourth, we investigated an integrated care model among a safety net population that actively incorporates health promotion and efforts to catalyze social connectedness.

Our findings add to the mixed literature on the impact of BHH on acute service utilization.28,35,36 Krupski and colleagues found reduced all-cause hospitalizations in an established BHH program but not a newer one, and no BHH impact on ED use.28 Evaluation of the Health Home demonstration in Missouri (while not solely a BHH intervention) showed reduced hospitalizations and ED use among enrollees. Service use reductions occurred after only one year, inclusive of a lengthy ramp-up period, and as Krupski et. al suggest, greater impact on service utilization might accrue with longer follow-up and program maturation. Importantly, our findings of reduced utilization were driven not by the number of patients that utilized acute services, but the number of visits among those who used acute services at least once. The BHH may therefore have helped stabilize frequent users of acute services, perhaps from care coordination, population management, or patient participation in group/social programming. However, no improvements were seen in metabolic outcomes among diabetic patients. Follow-up at later time periods is warranted to assess if the intervention improves these important outcomes.

The lack of association between BHH participation and reductions in medical inpatient utilization was unexpected. One possible explanation is that intervention components emphasized health promotion activities designed to improve long-term health rather than stem acute medical service utilization. Additionally, most BHH participants had access to some degree of medical care prior to BHH implementation, so the availability of on-site medical care might therefore have provided only incremental improvement in access to medical care.

The association of BHH participation and reductions in psychiatric hospitalizations and ED utilization is consistent with the theory that program elements may improve utilization outcomes by bolstering social support and connectedness. While there is an extensive older literature about the importance of social networks in adults with serious mental illness,37–43 this aspect has been largely neglected in modern service design and delivery. This theory was, however, considered in a recent analysis of injectable antipsychotic efficacy, in which authors hypothesized that greater contact with service providers may have driven lower relapse rates.44 While that study considered patient-provider contact rather than peer-to-peer support, it highlights the impact of treatments’ pro-social elements. Further investigation is needed on whether incorporating psychosocial elements into BHH programs may influence outcomes.

Improved rates of metabolic monitoring likely stemmed from registry-driven attention to screening, which began six months into the intervention. That significant improvements were found for HbA1c screening after only six months, and approached significance for LDL screening (but not glucose screening), likely reflects programmatic emphasis on HbA1c/LDL monitoring. Previous investigations have demonstrated that population-level attention to monitoring improves screening,45 and it is hoped that comprehensive screening will improve health outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several potential limitations. First, mental health symptom measures are currently unavailable in EHR, precluding assessment of BHH impact on mental health outcomes. Propensity score weighting balanced BHH and non-BHH patient groups for observable baseline characteristics, but since the BHH was designed for high-risk patients, the BHH may have preferentially enrolled higher acuity patients on unobservable factors. It remains possible that unobserved factors contributed to differences in outcomes, independent of BHH participation; associations found should therefore not be interpreted causally. Additionally, we did not differentiate between whether visits to the ED were driven by medical or psychiatric needs. Because medical and psychiatric etiologies for ED visits are so closely intertwined, and because of the limited time available for thorough psychiatric diagnosis, we do not feel ICD-9 codes corresponding to ED visits represent a valid or reliable indicator of reasons for ED visits. We were similarly unable to differentiate based on service provider because emergency psychiatric services are offered as consultations within medical ED’s in our health system, and are not assigned a distinct provider code. This gap represents an important avenue for future research. Finally, this real-world intervention was implemented incrementally over 12-months. Results may therefore understate the program’s potential impact.

Conclusions

The BHH program was associated with significant reductions in ED visits and psychiatric hospitalizations, and increased HbA1c monitoring among adults with psychotic and bipolar disorders. This study adds to prior evaluations of BHH initiatives by specifying program elements and psychiatric diagnoses, and distinguishing medical from psychiatric hospitalizations. Better understanding BHH implementation and outcomes provides insights for health systems looking to incentivize care models capable of improving health care quality, costs, and outcomes46 for this population with complex health needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Institutes of Mental Health (T32MH01973)

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Previous presentation: Data have not been previously presented at a meeting.

Contributor Information

Miriam C. Tepper, Cambridge Health Alliance - Department of Psychiatry, Somerville, Massachusetts Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry, Boston, Massachusetts.

Alexander Cohen, Cambridge Health Alliance - Department of Psychiatry, Somerville, Massachusetts.

Ana Progovac, Cambridge Health Alliance - Center for Multicultural Mental Health Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry, Boston, Massachusetts.

Andrea Ault-Brutus, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Stephen Leff, Cambridge Health Alliance - Department of Psychiatry, Somerville, Massachusetts; Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry, Boston, Massachusetts.

Brian Mullin, Cambridge Health Alliance - Department of Psychiatry, Somerville, Massachusetts.

Carrie Cunningham, University of California, San Francisco – Psychiatry.

Benjamin Lê Cook, Cambridge Health Alliance - Psychiatry, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Harvard Medical School - Psychiatry, Boston, Massachusetts.

References

- 1.McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. Schizophrenia: a concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiologic reviews. 2008;30:67–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA psychiatry. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ösby U, Brandt L, Correia N, Ekbom A, Sparén P. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Archives of general psychiatry. 2001;58(9):844–850. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suetani S, Whiteford HA, McGrath JJ. An Urgent Call to Address the Deadly Consequences of Serious Mental Disorders. JAMA psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1166–1167. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brugha TS, Wing JK, Smith BL. Physical health of the long-term mentally ill in the community. Is there unmet need? The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1989;155:777–781. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones DR, Macias C, Barreira PJ, Fisher WH, Hargreaves WA, Harding CM. Prevalence, severity, and co-occurrence of chronic physical health problems of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.) 2004;55(11):1250–1257. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viron M, Zioto K, Schweitzer J, Levine G. Behavioral Health Homes: An opportunity to address healthcare inequities in people with serious mental illness. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Druss BG. Improving medical care for persons with serious mental illness: challenges and solutions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 4):40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradford DW, Kim MM, Braxton LE, Marx CE, Butterfield M, Elbogen EB. Access to medical care among persons with psychotic and major affective disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2008 doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.8.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophrenia research. 2006;86(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggarwal A, Pandurangi A, Smith W. Disparities in breast and cervical cancer screening in women with mental illness: a systematic literature review. American journal of preventive medicine. 2013;44(4):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Cai X, Du H, et al. Mentally ill Medicare patients less likely than others to receive certain types of surgery. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2011;30(7):1307–1315. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. Jama. 2000;283(4):506–511. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lord O, Malone D, Mitchell AJ. Receipt of preventive medical care and medical screening for patients with mental illness: a comparative analysis. General hospital psychiatry. 2010;32(5):519–543. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(10) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, Rosenheck RA. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Archives of general Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Locus of mental health treatment in an integrated service system. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(7):890–892. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Annals of family medicine. 2009;7(2):100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerrity M. Integrating Primary Care into Behavioral Health Settings: What Works for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 24.The Lewin Group and Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Approacheds to Integrating Physical Health Services into Behavioral Health Organizations: A Guide to Resources, Promising Practices, and Tools. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alakeson V, Frank RG, Katz RE. Specialty care medical homes for people with severe, persistent mental disorders. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2010;29(5):867–873. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maragakis A, Siddharthan R, RachBeisel J, Snipes C. Creating a 'reverse' integrated primary and mental healthcare clinic for those with serious mental illness. Primary health care research & development. 2016;17(5):421–427. doi: 10.1017/S1463423615000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowersox NW, Lai Z, Kilbourne AM. Integrated care, recovery-consistent care features, and quality of life for patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.) 2012;63(11):1142–1145. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krupski A, West II, Scharf DM, et al. Integrating Primary Care Into Community Mental Health Centers: Impact on Utilization and Costs of Health Care. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.) 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500424. appips201500424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Glick GE, et al. Randomized Trial of an Integrated Behavioral Health Home: The Health Outcomes Management and Evaluation (HOME) Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050507. appi. ajp. 2016.16050507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilmer TP, Henwood BF, Goode M, Sarkin AJ, Innes-Gomberg D. Implementation of Integrated Health Homes and Health Outcomes for Persons With Serious Mental Illness in Los Angeles County. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.) 2016;67(10):1062–1067. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heaney CA, Israel BA. Social networks and social support. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 2008;4:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. Journal of economic surveys. 2008;22(1):31–72. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Statacorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuster JM, Kinsky SM, Kim JY, et al. Connected Care: Improving Outcomes for Adults With Serious Mental Illness. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE. 2016;22(10):678–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CARE APII. Gold Award: Community-Based Program: A Health Care Home for the "Whole Person” in Missouri’s Community Mental Health Centers. Psychiatric Services. 2015;66(10) doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.661013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bengtsson-Tops A, Hansson L. Quantitative and qualitative aspects of the social network in schizophrenic patients living in the community. Relationship to sociodemographic characteristics and clinical factors and subjective quality of life. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2001;47(3):67–77. doi: 10.1177/002076400104700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammer M. Social support, social networks, and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1981;7(1):45–57. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beels CC. Social support and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1981;7(1):58. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipton FR, Cohen CI, Fischer E, Katz SE. Schizophrenia: A network crisis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1981;7(1):144–151. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beels CC. Social Networks, the Family, and the Psychiatric Patient Introduction to the Issue. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1978;4(4):512–521. doi: 10.1093/schbul/4.4.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammer M, Makiesky-Barrow S, Gutwirth L. Social networks and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1978;4(4):522–545. doi: 10.1093/schbul/4.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breier A, Strauss JS. The Role of Social Relationships in the. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:949–955. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.8.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buckley PF, Schooler NR, Goff DC, et al. Comparison of Injectable and Oral Antipsychotics in Relapse Rates in a Pragmatic 30-Month Schizophrenia Relapse Prevention Study. Psychiatric Services. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500466. appi. ps. 201500466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nicol G, Campagna EJ, Garfield LD, Newcomer JW, Parks J, Morrato E. Clinical Setting and Management Approach Matters: Metabolic Testing Rates in Antipsychotic-Treated Youth and Adults. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC) 2016;67(1):128. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health affairs. 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.