Abstract

Objective

Among teens with asthma, challenges of disease management may be greater in those with a body mass index (BMI) >85th percentile compared to youth within the parameters for normal weight-for-age. This mixed-methods study assessed teens’ awareness of the link between weight and asthma management, and perspectives on how medical providers might open a discussion about managing weight.

Method

Teens aged 13–18, having BMI >85 percentile and chronic asthma, identified using health system databases and a staff email message board, were invited to complete a semi-structured, in-depth phone interview. Interviews were audio taped, transcribed, and qualitatively analyzed, using the Framework Method. Responses were summarized and themes identified. Descriptive summaries were generated for a 16-item survey of weight conversation starters.

Results

Of 35 teens interviewed, 24 (69%) were girls, 11 (31%) boys, 20 (63%) African-American. All teens reported having “the weight conversation” with their doctors, and preferred that parents be present. Half knew from their doctor about the link between being overweight and asthma, others knew from personal experience. Nearly all expressed the importance of providers initiating a weight management conversation. Most preferred conversation starters that recognized challenges and included parents’ participation in weight management; least liked referred to “carrying around too much weight.”

Conclusions

Most teens responded favorably to initiating weight loss if it impacted asthma management, valued their provider addressing weight and family participation in weight management efforts. Adolescents’ views enhance program development fostering more effective communication targeting weight improvement within the overall asthma management plan.

Keywords: Obesity, education, pediatrics, management/control

Introduction

Asthma management may be more of a challenge in overweight adolescents compared to normal weight youth. Multiple studies have demonstrated that being overweight increases the risk of physician-diagnosed asthma [1], is associated with more health utilization due to asthma [2,3], and potentially makes asthma more difficult to control [3–7]. On average, obese adolescents with asthma report greater respiratory symptoms [4,5] and respond less robustly to inhaled corticosteroids [6,7]. Further, risk for excess weight gain increases because of reduction in physical activity based, in part, on concerns about exercise-induced symptoms [8,9].

A sub-analysis utilizing the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey confirms that physician-initiated discussions related to their patients’ weight status are associated with clinically significant patient weight loss [10]. Some physicians are reluctant to discuss weight management due, in part, to their own negative bias or caution due to the stigma around overweight and limited appointment time to raise a sensitive topic [11–13]. Physicians may benefit from learning adolescents’ feelings about discussing weight and possible motivations to make changes. An important feature in this conversation may be incorporating the link between overweight and asthma symptoms, supported by better knowing how teens perceive messages that launch deeper discussions on this topic [14].

Factors governing asthma management are varied and complex, as are the factors governing weight management, with influence from environmental and genetic factors. Current recommendations include exploration of environmental factors (socioeconomic status, family involvement, healthy food availability) that may influence patient behaviors, and a “patient-centered” approach, defined by the Institute of Medicine as “providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.” [15].

In the spirit of incorporating the voices of people living with obesity [16], the purpose of this mixed-methods study was to hear from overweight adolescents with persistent asthma, and report on doctor-adolescent conversations about the link between asthma symptoms and overweight. We report adolescents’ views on the most and least effective approaches to introduce discussions on weight management [17]. Our goal is to encourage and guide more effective provider-generated discussions targeting overweight adolescents, using a patient-centered approach [10, 18, 19]. These findings will facilitate the development and evaluation of patient-centered and culturally appropriate tools that, in turn, facilitate conversations between providers and adolescents which link weight and asthma.

Methods

Adolescents meeting the study requirements were invited to participate in a one-time, in-depth telephone interview. Eligible adolescents were 12–18 years old, met Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set criteria for persistent asthma, had a body mass index (BMI) ≥85th percentile by age and sex [20–22], and were English speaking. Adolescents were identified using health system automated data, or additional recruitment strategies directed to parents via four postings in the current research section of health system’s daily employee email message board (Morning Post). Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) preliminary to an Agency for Health-care Research and Quality-funded intervention study “Developing Patient-Centered Approaches to Asthma Management in Obese Adolescents” (IRB# 8298).

A recruitment letter, sent to adolescents’ parents by regular mail, described the study. Eligibility screening was conducted by phone with parents/guardians for potential participants under the age of 18. If permission was granted, a packet containing consent/assent forms and a postage-paid return envelope was mailed to the parent. Upon receiving consent/assent, parents were called to schedule an interview with their teen. Up to six attempts within 2 weeks and across various times of the day were made to re-contact the consenting family before the adolescent was considered a passive refusal. Participating adolescents were mailed a $25.00 gift card after completing interviews.

Semi-structured, in-depth telephone interviews were conducted from May through July 2014. The research team developed a series of open-ended questions for the interview guide based on a literature review of asthma and obesity. Questions focused on assessing adolescents’ management goals for living with asthma, awareness of the link between weight and asthma, conversations with their physician about weight, and the role of a provider in discussing weight management (Table 1). Three interviewers trained in qualitative data collection conducted the telephone interviews.

Table 1.

In-depth interview guide

| Asthma Control |

| 1. What kinds of things in your daily life are interrupted because you have asthma? |

| 2. When you hear this “Asthma control” or “control of your asthma”—what does that mean to you? |

| 3. What is the goal of having your asthma controlled? |

| 4. In your own words, how important is it to you to have your asthma under control? |

5. As you think about how things are going with your asthma, could your asthma be better controlled?

|

| Unhealthy Weight |

| 1. To what extent are you aware that unhealthy body weight has an impact on management of asthma? |

| 2. There is some evidence that asthma medication can work better if the person taking it is at a healthy weight. Are you aware that asthma medication might work differently, and possibly work more effectively, if a person is at a healthy weight? |

| 3. Some people think they should lose weight and some people really don’t think they need to. Where are you on that? |

| Physician Communication |

| 6. What would you think if your doctor talked to you about your own weight? |

7. Has your doctor ever talked with you about your weight?

|

| 8. If you ever talked to your doctor about your weight was anything said about setting goals around your weight? |

| 9. How, if at all, can the doctor help you get to a healthy weight? |

| 10. As far as getting started with a conversation about somebody’s weight, some people say that it works better if, first, your doctor asks if it’s okay to talk about your weight. What do you think of that idea? |

| 11. What are your ideas on how your doctor can tell if you are ready to have a discussion about your weight? |

| 12. What questions should your doctor ask to find out if you or someone else is ready to talk about getting to a healthier weight? |

| 13. What effect would it have on you if your doctor discussed your weight in relation to how it affects your asthma? |

| 14. If weight loss was a recommendation to help you control your asthma, would that make a difference to you? |

| What would you consider? Would it make you more likely to take action to lose weight? |

Qualitative data analysis

Qualitative analysis of the transcribed interviews was completed by four research team members (GA, HAO, TT, and CM). The Framework Method used for this analysis employs a grid structure or matrix to allow researchers to develop descriptions, to categorize and compare data in the process of developing themes from interview transcripts [23]. The initial analysis categories were selected based on questions assessing research priorities. Reviewers read all transcripts at least twice and charted data by entering relevant direct quotes from assigned transcripts. Each transcript was charted in the matrix as a separate case (row) [23], allowing review of each participant’s content, and comparison across participants by item content. Coding was completed after establishing consensus on targeted topics/codes and reaching calibration. Twenty-five percent of transcripts were reviewed and calibrated by the team of 4 reviewers with concordance rates greater than 90%. Periodic consensus checks continued throughout the coding process. Reviewers reviewed each selected transcript to check for agreement or consensus. If coders disagreed, rationale for coding was provided and a decision for coding was made based on consensus.

Quantitative data analysis

At the end of the interview, adolescents answered a survey assessing asthma morbidity and clinical questions. Finally, adolescents rated 16 statements that might be used by a provider to open a discussion about weight and weight management [17], using a three-point Likert-type scale with 1 = don’t like, 2 = okay, and 3 = really like. SAS statistical software programming version 9.3 was used to calculate frequencies and cumulative percent of responses. Results were reported as means and standard deviations, where appropriate.

Results

Semi-structured interviews were completed by 35 adolescents meeting study eligibility. Of these, 69% (n = 24) were girls, 63% (n = 22) self-identified as African-American; the remaining 37% (n = 15) were white, and over 90% were non-Hispanic. (Table 2) The average age was 14.9, SD 2.1, ranging from 12 to 18 years, and average age at asthma diagnosis was 4.0 ± 4.2 years. Forty percent (40%) of the participants were currently taking three or more prescription medications. With unmanaged asthma as an eligibility criteria, eight adolescents (23%) visited the emergency department, four (11%) had been hospitalized, and one (3%) admitted to the intensive care unit in the previous year due to asthma.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (n = 35)

| Factors | |

|---|---|

| Current age* (years; mean ± SD) | 14.9 ± 2.1 |

| Range: 12–18 | |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Boys | 11 (31.4%) |

| Girls | 24 (68.6%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| African American/Black | 22 (62.9%) |

| Caucasian/White | 13 (37.1%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 33 (94.3%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.9%) |

| Unsure | 1 (2.8%) |

| Age at asthma diagnosis (years; mean ± SD) | 4.02 ± 4.15 |

| Current number of prescribed asthma medications, n (%) | |

| None | 13 (37.1%) |

| 1 | 2 (6.0%) |

| 2 | 5 (14.2%) |

| 3 | 8 (23.0%) |

| 4 or more | 6 (17.1%) |

| Unknown | 1 (3.0%) |

| ≥1 Emergency Department visits due to asthma in previous year, n (%) | |

| Yes | 8 (23.0%) |

| No | 26 (74.2%) |

| Unknown | 1 (3.0%) |

| ≥1 Hospitalizations due to asthma in previous year, n (%) | |

| Yes | 4 (11.4%) |

| No | 30 (86.0%) |

| Unknown | 1 (3.0%) |

| ≥1 Intensive Care Unit visit due to asthma in previous year, n (%) | |

| Yes | 1 (3.0%) |

| No | 33 (94.2%) |

| Unknown | 1 (3.0%) |

Age at time of interview.

Qualitative findings

Responses to the in-depth interview questions were summarized and appear in this report in the order of the interview questions. Before asking adolescents about their awareness of the link between being overweight and asthma control, we asked about impressions of their weight and thoughts about asthma control. Sections of this report include the adolescents’ knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, experiences, and preferences related to communications with their physicians about asthma and weight. Exemplary quotations from the participants are included under each description in tables and text.

Adolescents’ views on asthma and asthma control

Good control and worry

Good asthma control was interpreted by participants as being able to behave more like other adolescents, participating and playing in sports more vigorously, being more physically active and having more stamina. In the sequence of questions about their asthma control and the extent that asthma compromised school and social activities, a theme of worry about health emerged consistently give examples of the importance of “good control,” adolescents consistently included statements that included feeling less worried about having an asthma attack, not having to go to the hospital, and having enough breath to talk. A few comments included having a sense of good health as part of having good asthma control. “Feeling good” was woven between expressions of worry, for example, “[feeling] really good because … like I won’t be rushing to the hospital.”

Appraisals of body weight and the weight conversation

Acceptance

Early in the interview, adolescents were asked to evaluate their perception of need to lose weight by declaring a number on a scale of 1–10, with 1 meaning “I don’t need to lose any weight” and 10 meaning “I really do need to lose some weight.” All adolescents indicated that they needed to lose some weight. Fifty percent (50%) of the adolescents provided a rating of “4” to “7”, and the rest said close to “10”, plus one adolescent responding “12”. Some comments revealed recognition of a weight issue, such as “7 out of 10, not terrible, not where I should be” and “4 or 5, probably about 30 pounds to lose and have already lost about that.” A high percentage (77%) said they had previously experienced a conversation with their doctor about their weight, and many indicated the conversation reoccurred over many years. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Worry, weight conversation, and teens’ reactions

| Worry and asthma control | “ …you don’t really need to worry … That I might talk with [enough] air, like when I don’t have to take in air” and “really good because … like I won’t be rushing to the hospital.” |

| “… don’t want to have to go to the hospital and be hooked up to various breathing machines” | |

| “…not having to go to the emergency room so often” | |

| “…no asthma attacks …I’ll be feeling like very good and I don’t have to worry about being sick and being irritated.” | |

| Teens’ views of providers asking about weight | “Honestly, I’m OK with it. Wouldn’t be that big a deal” |

| “I wouldn’t feel that bad because they just end to help you and make you more aware of – that you need to, if you do.” | |

| “Something we need to discuss, would be OK.” | |

| “I would want them to say something if, like if like my weight is bad or something or if it’s not good, like to say something about it.” | |

| “comfortable, because they are medical professionals trying to give the best answers to your health” | |

| “… the doctor is interested in my health and wants me to live longer” | |

| “ …tend to feel OK about it because I have been told by other people like my mom or the doctor or nurse” | |

| Discomfort with the weight conversation | “…pretty used to it, more embarrassed than surprised.. must be doing something wrong.” |

| “I would just have to listen … I knew I could have done better” | |

| “It is really irritating … all the doctor talks about is my weight” | |

| “…feel a little disappointed and try to do something. OK with it [conversation]” | |

| “… stressful, more depressing – it is a big transition” [expressed by teen answering “12” for his need to lose weight] | |

| “I have struggled with that for a while, feeling kind of self-conscious about it. They didn’t really talk tome in a way that made me feel self-conscious. It was just my personal self about that.” | |

| “She [provider] can tell a lot by the face that’s nonverbal and actions… You can always tell if a person is ready or not for that conversation. Are they squirming in their seats? I know I used to squirm a lot when I felt uncomfortable…” |

When asked “what would you think if your doctor talked to you about your weight?”, mixed feelings emerged. Two-thirds of adolescents expressed familiarity and said that they were fine with that or said that they wouldn’t “feel bad” while some revealed their discomfort. A couple of adolescents responded that bringing up and talking about their weight was part of the doctor’s job, for example, “she’s supposed to tell you.” Most stated that the reason for the conversation illustrated the doctor’s concern and desire to help improve their health. Four adolescents expressed that they “knew it was coming” and were not surprised since it was a frequent topic during health visits. Another revealed currently feeling “comfortable” with the discussion “ …because I’m already losing weight.”

Discomfort with the weight conversation

To the question of “how can your doctor tell if you are ready to have a discussion about your weight,” the variety of responses again illustrated the sensitive nature of the conversation, from reluctance to perceived benefits. A third of adolescents expressed discomfort with a weight conversation. For some, this was followed by further reflection revealing a motivation to change following that difficult conversation. Responses to several questions revealed body language as a signal that the doctor should not press them to talk about weight because they would feel upset or defensive, with one saying “I will listen and not look at them as they are picking on me …I know it’s true … I need to work on it.” (Table 3) One adolescent’s memory was that the “conversation was done in a rude way … (I) felt disrespected because the doctor just told (me) how unhealthy (I) was.” Further comments from another adolescent revealed her awareness of being overweight, saying she would feel “a little sad, a little upset …” and continuing that “[hearing from her doctor would] motivate me to lose it [extra weight].” The remaining adolescents expressing discomfort said that the weight conversation made them feel self-conscious or uncomfortable, or as one participant said, if the doctor talked about his weight, he would be “disappointed” to acknowledge there was an issue with his weight.

Providers’ words and motivation to change

Conversations with the doctor about weight management encouraged many adolescents and made a positive impression, further revealing the importance of hearing the provider’s comments. For most, talking about weight occurred in reference to the BMI chart. One adolescent expressed a boost in motivation, saying “coming from a medical perspective, I should proceed as he says …” (Table 4) For many, the doctor’s comments were linked with the relationship to the adolescent’s health in general, for example, “work on weight and most things will change.” Another adolescent said, “he needed to get me down [to a lower weight] because he doesn’t want it affecting [my] heart and lungs” and repeating the provider’s message that “the heavier you are, the more strain on the body.” Another participant revealed a mixture of concern and appreciation, by saying “I know I need to work out and get healthy. I don’t want cardiac arrest or bad health at a young age.”

Table 4.

Providers’ words and motivation to change

| Linking weight and improved asthma management | “Yes, I would probably maintain a healthy weight because then my asthma is under control and I would probably feel healthier and better. So, yeah, I would.” |

| “I think it would be helpful if people could see that there is a connection and it’s not just two random things that we’re trying to take care of … knowing there was a connection helped kind of make me feel better about consistently exercising. It definitely helps you keep going and like exercising was hard. Just knowing they’re related and so that kind of helps” | |

| “Yes, really want to get rid of asthma, helps and self-esteem, make me listen to lost weight. | |

| “I would probably take it a little more serious than I do now because your asthma has a lot to do with like your whole life. I know my weight is pretty important, but actually if you think about it… the asthma is more important than keeping the extra weight…so if I do more—forced to lose weight…I kind of like [the doctor to use] the word “threat” because it’s kind of scary and useful” | |

| “Oh, maybe I put it into perspective and I won’t be—my breathing probably won’t be as bad” | |

| Weight and asthma symptoms, medication effectiveness, suggested words used by the doctor | “I am very aware of it because when I was younger, I used to be kind of heavy for my age. And I feel like that’s what caused quite a bit of what I went through with asthma” |

| “…my doctor wanted me to get to a healthy weight” [to help manage asthma] | |

| “Pretty aware, the heavier I am, the worse it [asthma symptoms-is…” | |

| I know for a fact that my weight has a lot to do with my asthma. … If I had [gone] back down to the weight that I was then, I wouldn’t be breathing as heavy all the time.” | |

| “I think medication would work for everyone the same, weight shouldn’t affect it” and “…they might have to take the medication more than normal, but just working [differently] overall, no.” | |

| “I don’t remember her talking about how it affect my asthma, but I would want to listen to her if it did have a very impact on my asthma. … [suggested doctor’s words:] “I notice there is something in your weight that could possibly really affect the asthma. So could you want to talk about this?” | |

| “Not too many medical terms because a lot of people don’t know those … if a person has a constant battle with it everyday, then I’m pretty sure that the person would want to work on their weight…” |

Adolescents’ suggestions for permission, words, and tone

When adolescents were asked for their opinions about getting their permission before a provider started to talk about weight, 100% of participants expressed a positive agreement. One said “[asking permission] is a better idea than just talking about it straightforward, because some people aren’t comfortable with talking about it.” One adolescent endorsed requesting permission plus acknowledging any changes that had been made, saying “‘You’re at a risky weight, so would you like to talk about it?’ noting how great you’ve been doing to keep weight managed.” (Table 4)

Further suggestions were offered that the provider might open the topic of weight in a gentle way, “ease into the conversation” or be “soft spoken” and considerate of someone’s feelings. One adolescent felt uneasy because the doctor was not familiar to her.

“It is uncomfortable. It’s because sometimes you may hear your parents telling that you need to start eating healthier, but it’s kind of intimidating coming from a person who is not a part of your family or basically kind of a stranger, even though they are your doctor or primary care physician …”

A few adolescents expressed dissatisfaction with a provider just pointing out their high weight and then not discussing the topic further. One adolescent said she was “irritated” because she felt the provider was simply saying “‘you’re overweight’ and that’s it.” Another adolescent preferred a more in-depth conversation by saying, “if [the doctor] will sit down and actually talk to me about my weight, that’s fine.” Several adolescents (25%) suggested asking their perspective while talking about BMI, for example, “what do you think about losing weight?” and another suggested “do you feel okay with your weight?” Another teen talked of his struggle with weight over time, saying he needed inspiration to help build motivation to change. He suggested that the provider connect weight control to values and important activities in the adolescent’s life by saying, “talk about what gets me excited.” (Table 4).

Include parents

Nearly all adolescent participants suggested that parents or guardians be part of the conversation regarding their child’s weight and asthma control, both to increase awareness and because parents are largely responsible for their child’s well-being. As one adolescent said, “… what the parent does affects how the person eats.” One adolescent indicated that the combination of provider and parent would be motivating, saying “…if you hear one person say it, like a friend or a neighbor, probably you won’t really care about it. But then, if you have like your parents and the doctors telling you that they think you should take action to it, yeah, take action to it.”

Link between asthma and weight

Nearly 75% of the respondents were aware that extra weight affected their asthma. Over half knew about the link between asthma control and being overweight from talking with their doctor; nearly one-fourth figured it out from their personal experience. One adolescent said he knew that weight caused breathing problems which, in turn, might affect asthma (Table 4).

Asked about their awareness that asthma medications might work more effectively “if a person was at a healthy weight”, few adolescents reported being aware of this. About half said they were not sure or not aware, or “never thought about it.” A few teens revealed their beliefs that medications worked the same, regardless of one’s body weight.

Recommending weight loss to help control asthma

Finally, adolescents were asked about their response if the doctor discussed weight in relation to how it affects their asthma. (Table 4) Of those responding, more than half gave positive responses, and only one gave a negative response. One adolescent said that information would be “eye opening” and, if said in an understandable manner, would be motivation for improving asthma control. This is illustrated by the comment, “[it would] make me more aware so I can fix it.”

Further, we asked if participants would be more likely to take action “if weight loss was recommended to help you control your asthma.” Responses were largely positive, ranging from a “yes” to “absolutely” (77%). Some said making this link would promote “a new perspective” and encourage consideration of weight management suggestions “a little more seriously.” Hearing this connection revealed a new source of motivation and inspired self-management, illustrated by one participant, “I would just feel very agreeable because sometimes I may realize that I’m making a mistake if I’m doing something to gain weight.”

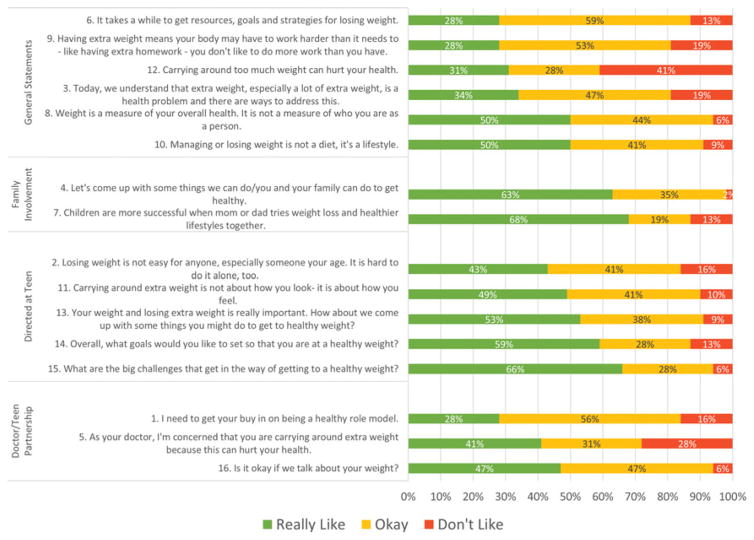

Weight conversation starters

During the final step of the interview, participants were asked their preferences for a set of 16 statements that could be used to open the discussion about managing their weight. These had been used and encouraged previously as part of a community program [17]. Of the 35 adolescents completing the telephone interview, n = 32 completed the survey. (Figure 1) Overall, participants responded positively to all 16 statements. Fourteen statements received over 80 percent of respondents rating them either “Really Like” and “OK.” There were no statements for which the “Don’t Like” outweighed the positive responses.

Figure 1.

Teen ratings of introduction statements for weight discussion (n = 32).

Adolescents were the most receptive to hearing, “Let’s come up with some things we can do/you and your family can do to get healthy (#4),” with nearly all (97%) rating this as positive. Statements that related to doctors asking adolescents for permission (#16), about potential challenges (#15), or asking about goals (#14) also scored high with over 87% rating these three statements positively. The least positive statement, “Carrying around too much weight can hurt your health,” had just under 60% of responders giving a positive rating.

The four most preferred statements based on ratings of “really like,” supported parents as part of the weight management effort, and acknowledged challenges and importance of identifying goals.

Children are more successful when mom or dad tries weight loss and healthier lifestyles together. (70%)

What are the challenges that get in the way of getting to a healthy weight? (68%)

Let’s come up with some things/we/you/you and your family/can do to get healthy. (65%)

Overall, what goals would you like to set up so that you are at a healthy weight? (60%)

Discussion

A growing body of literature supports the role of obesity in the modulation of asthma severity and control [24]. Weight management and weight loss is a complicated, multi-faceted, and family-based issue, requiring a discussion that, optimally, engages and motivates both the adolescent and parent or guardian. Using a patient-centered approach, the objectives of this qualitative study were to better understand overweight adolescents’ views on their weight, their asthma management, and communications with providers about being overweight and its link to asthma management. By utilizing in-depth interviews, we learned about preferences for communication and motivations influencing efforts to address being overweight.

Adolescents in this study were aware of their overweight condition, and all participants had heard of or talked about weight problems with their doctor. Participants consistently expressed the importance of the provider talking to them about their weight. Most of the adolescents believed it was the doctor’s role to talk about weight, and expressed that they knew the doctor was talking about this issue because of a commitment to improving the adolescent’s health.

Providers have been advised to discuss health and health challenges during well-child visits; discussions will include overweight, following weight management guidelines, if applicable. [25] Possibly due to the sensitive nature of the weight discussion, physicians may not consistently mention the adolescent’s weight status during a medical visit [11]. Similarly, some of our participants expressed discomfort and sensitivity related to talking about weight. Our review further revealed that some discomfort may have been due to feelings of adolescents’ disappointment in themselves. For those who expressed discomfort, reasons stated reasons included stating that the adolescent was overweight but not discussing it, and little or no improvement in weight after repeated weight management conversations. Adolescents’ feelings about displaying negative body language to put off the weight conversation might aid interpretation of reluctance. Providers might acknowledge these factors contributing to adolescents’ discomfort, and further benefit from seeking permission to speak about weight.

Qualitative analysis helped to illustrate the extent of adolescents’ understandings of the link between weight and asthma control. All participants had talked to their provider about weight. Only half reported learning the link between asthma and being overweight from their doctor; a smaller group knew based on their own experience. Adolescents suggested strategies for broaching the subject of weight, after seeking permission to talk on that subject participants recommended making changes that were linked to key current interests, such as school or sports activities. Parents/guardians were viewed as important partners in this process. This echoes the goal of patient-centered care, which seeks partnership and shared decision-making and productive communication to discover needs and satisfying treatment goals of the patient [26]. This approach has been effective and successful in improving the care of patients living with asthma and has enhanced adherence to provider recommendations [10,16,27]. Our findings suggest that providers may help youth get to a healthy weight by including parents as partners. In addition, findings encourage directing the conversation to improving general health, making the link between improved asthma management and weight loss, and being direct after acknowledging that the conversation is not meant to foster discomfort.

Our study results should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. Participants with parent/guardian consent were willing to talk about weight and communication. We spoke with a fairly large number of adolescents, including boys and girls and a majority of African-Americans, although the data collected were from a single urban area, so findings cannot be generalized to a larger population. The findings can, however, be transferable to other similar clinical settings whereby providers are treating adolescents with unmanaged asthma and who are overweight. The interviews were completed by telephone which simplified the access to adolescents, but may have reduced the flow of conversation. The quality of responses may have been reduced by distraction from others nearby or the screen-time activities and/or their mobile devices, although interviewers requested participants to avoid these distractions during the interview.

Conclusions

Information from this study uncovered the worry and discomfort faced by adolescents due to difficult asthma management exacerbated, in part, by being overweight. Our analyses suggest that incorporating patient-centered communication principles may encourage enhanced self-management for these teens and, hopefully, reduce their worry. Such communication promotes a partnership of discovering factors most important to the patient and then utilizing these as motivations for improving health. This is an approach highly regarded in boosting the effectiveness of health promotion via behavior change recommendations, [26,28,29] improved patient satisfaction, and more accurate recall of medical advice [30]. Because of the psychosocial factors often associated with obesity and asthma, such as low self-esteem, depression, and low quality of life, [31,32] interventions should benefit from incorporating a patient-centered approach to providing care.

This study further illustrates the benefits of seeking and incorporating adolescents’ motivations in health behavior change. Provider recommendations boost motivation to tackle weight management [10,27,33,34], and linking overweight-related asthma symptoms could further enhance weight management among adolescents’ with asthma. Interventions that assess and bring together adolescents’ values and perspectives, patient-centered approaches of providers, and parent/guardian participation will likely amplify weight-related behavior changes that benefit asthma control in overweight teens [18,19,35].

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the participating teens and the work of research staff members Brianna Costello and Maggie Jones, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Funding

This study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HS022417).

Footnotes

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/ijas.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mannino DM, Mott J, Ferdinands JM, Camargo CA, Friedman M, Greves HM, et al. Boys with high body masses have an increased risk of developing asthma: findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30(1):6–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor B, Mannino D, Brown C, Crocker D, Twum-Baah N, Holguin F. Body mass index and asthma severity in the National Asthma Survey. Thorax. 2008;63(1):14–20. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.082784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black MH, Zhou H, Takayanagi M, Jacobsen SJ, Koebnick C. Increased asthma risk and asthma-related health care complications associated with childhood obesity. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(7):1120–1128. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black MH, Smith N, Porter AH, Jacobsen SJ, Koebnick C. Higher prevalence of obesity among children with asthma. Obesity. 2012;20(5):1041–1047. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trasande L, Liu Y, Fryer G, Weitzman M. Effects of childhood obesity on hospital care and costs, 1999–2005. Health A3 (Millwood) 2009;28(4):w751–w760. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pradeepan S, Garrison G, Dixon AE. Obesity in asthma: approaches to treatment. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13(5):434–42. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0354-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forno E, Lescher R, Strunk R, Weiss S, Fuhlbrigge A, Celedon JC, et al. Decreased response to inhaled steroids in overweight and obese asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):741–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leermakers ET, Sonnenschein-van der Voort AM, Gaillard R, Hofman A, de Jongste JC, Jaddoe VW, et al. Maternal weight, gestational weight gain and preschool wheezing: the Generation R Study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(5):1234–1243. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00148212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner S. Perinatal programming of childhood asthma: early fetal size, growth trajectory during infancy, and childhood asthma outcomes. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:962923. doi: 10.1155/2012/962923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pool AC, Kraschnewski JL, Cover LA, Lehman EB, Stuckey HL, Hwang KO, et al. The impact of physician weight discussion on weight loss in US adults. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2014;8(2):e131–e139. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford ES, Mannino DM, Redd SC, Mokdad AH, Galuska DA, Serdula MK. Weight-loss practices and asthma: findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Obes Res. 2003;11(1):81–86. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackburn M, Stathi A, Keogh E, Eccleston C. Raising the topic of weight in general practice: perspectives of GPs and primary care nurses. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008546. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein L, Ogden J. A qualitative study of GPs’ views of treating obesity. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(519):750–754. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rees RW, Caird J, Dickson K, Vigurs C, Thomas J. ’It’s on your conscience all the time’: a systematic review of qualitative studies examining views on obesity among young people aged 12–18 sources in the UK. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004404. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Institute of Medicine, The National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alberga AS, Russell-Mayhew S, von Ranson KM, McLaren L, Ramos Salas X, Sharma AM. Future research in weight bias: What next? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24(6):1207–1209. doi: 10.1002/oby.21480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Generation AfaH. Weigh In: A conversation guide for parents + adult cargivers of children. Agres 7–11 sources old. 2016 Available from: http://weighinguide.com/index.html.

- 18.Borrelli B, Riekert KA, Weinstein A, Rathier L. Brief motivational interviewing as a clinical strategy to promote asthma medication adherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christie D, Channon S. The potential for motivational interviewing to improve outcomes in the management of diabetes and obesity in paediatric and adult populations: a clinical review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(5):381–387. doi: 10.1111/dom.12195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11(246):1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becerra MB. Factors associated with increased healthcare utilization among adults with asthma. J Asthma. 2016 doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1218017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner S, Richardson K, Murray C, Thomas M, Hillyer EV, Burden A, et al. Long-Acting beta-Agonist in Combination or Separate Inhaler as Step-Up Therapy for Children with Uncontrolled Asthma Receiving Inhaled Corticosteroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon AE, Holguin F, Sood A, Salome CM, Pratley RE, Beuther DA, et al. An official American Thoracic Society Workshop report: obesity and asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7(5):325–335. doi: 10.1513/pats.200903-013ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGuire S Institute of Medicine (IOM) Early Childhood Obesity Prevention Policies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Adv Nutr. 2012;3(1):56–57. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson JM, Vos MB, Walsh SM, O’Brien LA, Welsh JA. Weight management-related assessment and counseling by primary care providers in an area of high childhood obesity prevalence: current pratices and areas of opportunity. Childhood obesity. 2015;11(1):194–201. doi: 10.1089/chi.2014.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonsson M, Egmar AC, Hallner E, Kull I. Experiences of living with asthma - a focus group study with adolescents and parents of children with asthma. Journal of Asthma. 2014;51(2):185–192. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.853080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qamar N, Pappalardo AA, Arora VM, Press VG. Patient-centered care and its effect on outcomes in the treatment of asthma. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2011;2:81–109. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis CC, Pantell RH, Sharp L. Increasing patient knowledge, satisfaction, and involvement: randomized trial of a communication intervention. Pediatrics. 1991;88(2):351–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padrnos L, Dueck AC, Scherber R, Glassley P, Stigge R, Northfelt D, et al. Quality of life and disease understanding: impact of attending a patient-centered cancer symposium. Cancer Med. 2015;4(6):800–807. doi: 10.1002/cam4.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porter SC, Forbes P, Feldman HA, Goldmann DA. Impact of patient-centered decision support on quality of asthma care in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):e33–e42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carcone AI, Naar-King S, Brogan KE, Albrecht T, Barton E, Foster T, et al. Provider communication behaviors that predict motivation to change in black adolescents with obesity. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34(8):599–608. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182a67daf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollak KI, Coffman CJ, Alexander SC, Ostbye T, Lyna P, Tulsky JA, et al. Weight’s up? Predictors of weight-related communication during primary care visits with overweight adolescents. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adeniyi FB, Young T. Weight loss interventions for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009339.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]