Abstract

Background

The role of diet in MS is largely uncharacterised, particularly as it pertains to pediatric-onset disease.

Objective

To determine the association between dietary factors and MS in children.

Methods

Pediatric MS patients and controls were recruited from 16 US centers (MS or clinically isolated syndrome onset before age 18, <4 years from symptom onset and at least 2 silent lesions on MRI). The validated Block Kids Food Screener questionnaire was administered 2011–2016. Chi-Square test compared categorical variables, Kruskal-Wallis test compared continuous variables, and multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed.

Results

312 cases and 456 controls were included (mean ages 15.1 and 14.4 years). In unadjusted analyses there was no difference in intake of fats, proteins, carbohydrates, sugars, fruits or vegetables. Dietary iron was lower in cases (p=0.04), and cases were more likely to consume below recommended guidelines of iron (77.2% of cases vs 62.9% of controls, p<0.001). In multivariable analysis, iron consumption below recommended guidelines was associated with MS (odds ratio=1.80, p<0.01).

Conclusion

Pediatric MS cases may be less likely to consume sufficient iron compared to controls, and this warrants broader study to characterize a temporal relationship. No other significant difference in intake of most dietary factors was found.

Keywords: case control studies, multiple sclerosis, nutritional, all pediatric, risk factors in epidemiology, neurology

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) typically onsets early in adulthood (ages 20–40), but may extend into extremes of age. Cases of pediatric-onset MS (before age 18) are thought to account for approximately 3–5% of currently adult MS patients, and constitute an important minority of cases as the study of factors early in life which could affect their disease may provide important insight into the disease more generally.1,2 Much remains to be elucidated in our understanding of MS pathophysiology,1 and the role of dietary factors in influencing MS risk and progression remains largely uncharacterised, yet is a topic of frequent concern and anxiety for patients and their relatives. Dietary modifications such as increased use of dietary supplementation or adherence to classically “healthy” diets such as a Mediterranean or a low-fat high fibre diet are often adopted by those affected on anecdotal indications.3 There are currently no dietary guidelines for patients with MS and their at-risk relatives. Disease association studies in this regard have so far focused on the roles of vitamin D and obesity, both of which are partly determined by diet, and for which a relatively consistent evidence base is now in place.4–5 Epidemiological findings such as that of latitudinal gradient of MS prevalence render the notion that MS is more prevalent in countries with a diet typically rich in its intake of calories, fat, dairy and sugar.6 The study of nutritional factors as they pertain to MS, and particularly pediatric MS, is however logistically difficult and as such, studies to date have often been conducted in adult MS patients some time after disease onset, incorporating long retrospective periods (prone to recall bias) and with multiple possible confounding factors and a resulting limited evidence base of inconsistent findings.7–9 The possibility of dietary components acting as possible modifiable factors in pediatric MS susceptibility or progression renders establishing differences in dietary behavior between cases and controls, if any, potentially important for guiding future work on risk and/or disease management. This study utilized data from a multi-center case-control study to investigate associations between dietary intake and pediatric MS.

Materials and methods

Pediatric MS cases and controls

Children with MS were recruited from 16 MS centers at general pediatric hospitals in the US (including University of California, San Francisco, State University of New York at Buffalo, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Children’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts General Hospital, Mayo Clinic Rochester, Stony Brook University Medical Center, Texas Children’s Hospital Baylor, Loma Linda, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Ann & Robert Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Children’s Hospital of Colorado, University of Texas Southwestern, Children National, Primary Children Salt Lake, Washington University St. Louis) to take part in an ongoing case-control study of genetic and environmental risk factors for pediatric MS. Children from these centers were eligible for inclusion if they were between ages 3 and 21, had MS (in accordance with the McDonald MS criteria) or clinically isolated syndrome onset prior to age 18, were less than 4 years from symptom onset and had at least 2 silent lesions on MRI.10 All cases were ascertained by a panel of at least two pediatric MS experts.

Control subjects were recruited from children under the age of 22 who were patients or siblings of patients at the same medical centers. Children were included if they had no personal history of autoimmune disease, no history of treatment with immunosuppressive therapy, no history of severe health conditions (individuals with asthma and eczema were included in the study), and no parental history of MS. Usually, one control subject was included per family and could be of any birth order within that family. Of note, there were two families with two eligible controls; in this case, the oldest child was selected for inclusion.

Questionnaires

Cases and controls or their parents, as appropriate, were asked to complete a standardized questionnaire before clinic visit incorporating the subject's development, environmental exposures, medical history, demographic information (including age, sex, self-reported ethnicity (Hispanic/non-Hispanic) and race (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander or White)). In the vast majority of cases the questionnaire was completed by the parents, as was true for both cases and controls. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board at each institution. All participants and one of their parents signed assent and consent forms before enrollment.

Dietary intake of fiber, fat, protein, carbohydrate, fruit, vegetables, dairy and iron was assessed through the Block Kids Food Screener (BKFS) self-report questionnaire, administered between November 2011 and January 2016 to cases and controls to be completed at the time of enrollment in the study. The included dietary variables were selected at the start of the study prior to commencement of analysis, and selected as they were included in a data dictionary listing nutrients for which the questionnaire was designed (not including for example reliable capture of vitamin D intake), and for which the authors felt there were putative mechanisms or previous suggestion of an influence on MS or other neurological diseases. The BKFS was developed in 2007 by NutritionQuest and is a simple method of dietary assessment that has been validated against three, 24-hour dietary recalls in children aged 10–17 and takes approximately 10–12 minutes to complete.11 The de-attenuated correlations (mitigating a weakening effect of measurement error on the correlation coefficient) for which the questionnaire was specifically validated (and from which other, particularly micronutrient information, was inferred) were fruit (de-attenuated correlation 0.60), vegetable (0.53), potatoes (0.88), legumes (0.82), whole grains (0.64), dairy (0.87), meat/fish/poultry (0.68), kcalories (0.66), protein (0.70), saturated fat (0.77), added sugar (0.48), glycaemic load (0.59), and glycaemic index (0.57).11

The questionnaire consists of 41 questions that evaluate the frequency and portions of foods and beverages consumed during the preceding week. For specific questions such as type of cereal and type of milk, participants were asked to select the response corresponding to the item they consumed the most. Subjects were instructed to select the frequency (none last week, 1 day, 2 days, 3–4 days, 5–6 days or everyday) and then the food-specific portion size (e.g 1 slice, 2 slices or 3+ slices) that most closely matched their intake. The USDA's My Pyramid Equivalents Database (MPED; version 2.0 for USDA Survey Foods, 2003–2004) was used in identifying defined cup equivalents for portion sizes, and the food codes from BKFS food list were linked to the USDA's Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies (FNDDS) and the USDA's MPED (Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals 2012).11 The food list used in the BKFS was determined by analysis of data collected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which incorporated almost 10,000 dietary recalls of 24 hour dietary recall information, 2002–2006.11 The nutrient and food group analysis database for the BKFS was based upon consumption and population weighted age-sex group of mean nutrient and food group dietary intake. 11

The BKFS was completed by subjects or their caregivers in accordance with instructions received from research staff. Subjects were excluded if they left >15 responses empty on the questionnaire or consumed an average daily calorie intake of <500 or >5000 kcal/day based on their responses (n=22 excluded based on <500 kcal/day caloric estimate).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Chi-Square test was used to compare categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables to test an association between dietary intake variables and disease status (case status vs. control status). Dietary intake recommended guidelines for different age groups were obtained from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010, and the Institute of Medicine (US) Food and Nutrition Board. 12–13 Multivariate logistic regression was done adjusting the results for age, sex, ethnicity, race, BMI and socioeconomic status using a multivariate logistic regression model.

Height and/or weight were missing for a number of participants (17 cases, 86 controls), and for these individuals it was not possible to calculate BMI. Using CDC stature-forage and weight-for-age growth charts, we approximated the age- and gender-specific z-scores of height and weight for cases and controls. We then applied the Markov chain Monte Carlo method of multiple imputation to obtain 10 imputed sets of z-scores for height and weight from case-control status, race, ethnicity, SES, and the dietary effects (protein, carbohydrate, fat intake etc.) Imputed sets of BMI were calculated for participants with missing height and/or weight data by back-transforming the z-scores for heights and weights. Sensitivity analyses were also performed by removing subjects for whom BMI was not available.

Results

Case and control characteristics

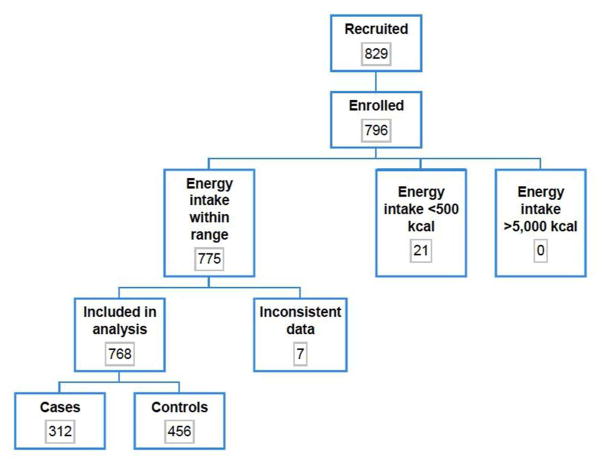

A total of 312 cases (mean disease duration 10.8 months) and 456 controls were included in the analysis population (percent females 62.5% and 52.9%, respectively; mean ages 15.1 and 14.4 years, respectively) (figure 1). Baseline demographic characteristics of cases and controls are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of number of participants (cases and controls) evaluated for study inclusion

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of cases and controls

| Subject

|

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 456) | Case (N = 312) | ||

| Disease Duration: Mean (SD) | - (-) | 10.8 (10.2) | |

| Age at onset/enrollment: Mean (SD) | 14.4 (3.7) | 15.1 (3.3) | 0.0011 |

| Gender | 0.0082 | ||

| Male | 215 (47.1%) | 117 (37.5%) | |

| Female | 241 (52.9%) | 195 (62.5%) | |

| Race | 0.6132 | ||

| Asian | 23 (5.2%) | 15 (5.2%) | |

| Black or African American | 69 (15.6%) | 55 (18.9%) | |

| White | 310 (70.3%) | 192 (66.0%) | |

| Other | 39 (8.8%) | 29 (10.0%) | |

| Ethnicity | <.0012 | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 83 (18.6%) | 88 (29.4%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 363 (81.4%) | 211 (70.6%) | |

| Mother highest education | <.0012 | ||

| None | 22 (5.2%) | 32 (10.9%) | |

| High school diploma | 188 (44.5%) | 167 (57.0%) | |

| Bachelor's or graduate degree | 200 (47.4%) | 94 (32.1%) | |

| Other | 12 (2.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Height (cm): Mean (SD) | 160.5 (16.6) | 160.8 (16.0) | 0.7611 |

| Weight (kg): Mean (SD) | 57.8 (21.1) | 67.3 (23.8) | <.0011 |

| Body Mass Index: Mean (SD) | 22.1 (5.7) | 25.3 (7.1) | <.0011 |

The variable DiseaseDurationMonth had 466 missing values.

The variable RaceGroup had 36 missing values.

The variable Ethnicity had 23 missing values.

The variable MomDiploma had 53 missing values.

The variable Height had 103 missing values.

The variable Weight had 73 missing values.

The variable BMI had 103 missing values.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

Chi-squared test of no association.

Mean dietary intake in cases and controls

Baseline dietary intake for various nutrients is shown for each group in Table 2. Average dietary intake of fiber, iron and dairy were significantly lower in cases compared to controls (p=0.04, p=0.04 and p=0.01, respectively)(Table 2). In analysis of males and females separately, only average dietary fiber consumption in males differed between cases and controls (12.5 vs 11.3 grams in controls vs cases, p=0.04).

Table 2.

Average dietary intake of cases and controls

| Control (N=456) | Case (N=312) | P-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients | |||

| Energy (kcal/day per 100kcal): Mean (SD) | 1347.1 (660.8) | 1297.3 (624.8) | 0.24 |

| Protein (g/day per 10 g): Mean (SD) | 59.1 (32.4) | 57.3 (32.2) | 0.34 |

| Carbohydrate (g/day per 10 g): Mean (SD) | 158.6 (75.9) | 152.0 (69.3) | 0.23 |

| Fiber (g/day): Mean (SD) | 11.3 (6.0) | 10.5 (5.7) | 0.04 |

| Fat (g/day per 10 g): Mean (SD) | 55.0 (30.2) | 53.0 (29.0) | 0.24 |

| Saturated fat (g/day per 10 g): Mean (SD) | 19.5 (10.6) | 18.4 (10.0) | 0.09 |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (g/day per 10 g): Mean (SD) | 18.7 (10.5) | 18.0 (10.1) | 0.27 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (g/day per 10 g): Mean (SD) | 8.1 (4.5) | 7.9 (4.3) | 0.49 |

| Micronutrients | |||

| Iron (mg/day): Mean (SD) | 9.8 (5.0) | 9.2 (4.9) | 0.04 |

| Food groups | |||

| Fruit (cup equivalent/day): Mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.0) | 0.43 |

| Vegetables (cup equivalent/day): Mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.77 |

| Dairy (cup equivalent/day): Mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.4 (0.9) | 0.01 |

| Sugar (tsp./day): Mean (SD) | 8.2 (6.5) | 8.2 (6.9) | 0.44 |

Kruskal-Wallis test

There was no significant difference between the mean calorie intake for cases (1297kcal/day) and controls (1347kcal/day)(p=0.24), and mean percentage energy intake from protein, carbohydrate and fat did not differ between cases and controls (17.5% vs 17.4%, p = 0.50; 47.6% vs 47.8%, p = 0.51; 36.3% vs 36.3%, p = 0.73, respectively). These remained insignificant in subgroup analysis of males and females separately. There was no difference between cases and controls in the likelihood of exceeding, being within, or consuming less than recommended dietary intake of protein, carbohydrate, fat or fiber. Cases were however significantly more likely to consume less than recommended average dietary intake of iron (77.2% of cases vs 62.9% of controls, p<0.001).

Multivariate association between dietary intake and pediatric MS

In analyses adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, race, BMI and socioeconomic status using a multivariate logistic regression model there was no difference between cases and controls in average dietary intake of energy, fats, proteins, carbohydrates, sugars, fruits, vegetables, dairy, fiber or iron (Table 3). However, multivariable analysis of categorical effects showed that “low” iron intake was associated with an increased MS risk (odds ratio=1.80, 95% CI 1.24–2.62, p<0.01)(Table 4). Further, multivariable models additionally adjusting for total energy intake did not markedly differ on any of the results. When analyses were repeated after removing subjects for whom BMI was imputed, the results were very consistent, and the magnitude and significance of the low iron effect remained (odds ratio= 1.70, 95%CI 1.15–2.52, p=0.01. When analyses were repeated including only overweight or obese subjects for whom BMI data were available, the data were similarly consistent (Table 5).

Table 3.

Odds ratio estimates from multivariable analysis of pediatric multiple sclerosis by nutrient intake*

| Nutrient | Adjusted analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | |

| Energy (kcal/day) per 100 kcal | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 |

| Protein (g/day) per 10 g | 0.99 | 0.94–1.05 |

| Carbohydrate (g/day) per 10 g | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 |

| Fat (g/day) per 10 g | 0.98 | 0.93–1.04 |

| Fiber (g/day) | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 |

| Iron (mg/day) | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 |

| Sugar/Syrup (tsp./day) | 1.00 | 0.98–1.03 |

| Fruit/fruit juices (cup equivalent/day) | 0.98 | 0.84–1.13 |

| Vegetables (cup equivalent/day) | 1.00 | 0.77–1.31 |

| Dairy (cup equivalent/day) | 0.86 | 0.73–1.02 |

| Saturated fat (g/day) per 10 g | 0.92 | 0.78–1.07 |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (g/day) per 10 g | 0.95 | 0.81–1.11 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (g/day) per 10 g | 0.92 | 0.63–1.33 |

| Protein per 10% daily calories** | 1.16 | 0.71–1.88 |

| Carbohydrate per 10% daily calories** | 1.00 | 0.82–1.21 |

| Fat per 10% daily calories** | 0.95 | 0.72–1.24 |

Multivariable analysis adjusted for gender, age, BMI, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (mother’s highest educational degree)

The daily calories constituted by protein, carbohydrate or fat intake for every 10% of total daily calories.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of categorical nutrient intake*

| Categorical nutrient intake** | Estimate | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein: Less than recommendations: Yes vs. No | 2.01 | 0.33–12.22 | 0.45 |

| Carbohydrate: Less than recommendations: Yes vs. No | 1.02 | 0.74–1.40 | 0.90 |

| Fat: Exceeds recommendations: Yes vs. No | 1.13 | 0.82–1.54 | 0.46 |

| Fiber: Less than recommendations: Yes vs. No | 1.87 | 0.47–7.44 | 0.38 |

| Iron: Less than recommendations: Yes vs. No | 1.80 | 1.24–2.62 | <0.01 |

Multivariable analysis adjusted for gender, age, BMI, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (mother’s highest educational degree)

- Total protein: Child ages 1–3= 13g, ages 4–8= 19g, ages 9–13= 34g, female ages14–18= 46g, male ages 14–18= 52g, female ages19–30= 46g, male ages 19–30= 56g

- Total carbohydrate: Child ages 1–3= 130g, ages 4–8= 130g, ages 9–13= 130g, ages 14–18= 130g, ages 19–30= 130g

- Total fiber: Child ages 1–3= 19g, child ages 4–8= 25g, male ages 9–13= 31g, female ages 9–13= 26g, male ages 14–18= 38g, female ages 14–18= 26g Iron: Child ages 1–3= 7mg, ages 4–8= 10mg, ages 9–13= 8mg, female ages 14–18= 15mg, male ages 14–18= 11mg, female ages 19–30= 18mg, male ages 19–30= 8mg

- Total fat (% of calories): Child ages 1–3= 30–40%, ages 4–18= 25–35%, ages 19–30= 20–35%

Table 5.

Odds ratio estimates by nutrient intake from multivariable analysis of overweight or obese pediatric multiple sclerosis cases (N=122) and controls (N=85)*

| Nutrient | Adjusted analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Energy (kcal/day) per 100 kcal | 0.97 | 0.92–1.02 | 0.20 |

| Protein (g/day) per 10 g | 0.95 | 0.86–1.05 | 0.32 |

| Carbohydrate (g/day) per 10 g | 0.96 | 0.92–1.01 | 0.10 |

| Fat (g/day) per 10 g | 0.96 | 0.87–1.06 | 0.38 |

| Fiber (g/day) | 0.97 | 0.92–1.02 | 0.21 |

| Iron (mg/day) | 0.97 | 0.91–1.03 | 0.32 |

| Sugar/Syrup (tsp./day) | 0.95 | 0.91–1.00 | 0.05 |

| Fruit/fruit juices (cup equivalent/day) | 0.82 | 0.60–1.11 | 0.20 |

| Vegetables (cup equivalent/day) | 1.27 | 0.75–2.15 | 0.36 |

| Dairy (cup equivalent/day) | 0.75 | 0.55–1.04 | 0.09 |

| Saturated fat (g/day) per 10 g | 0.84 | 0.63–1.11 | 0.21 |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (g/day) per 10 g | 0.87 | 0.65–1.17 | 0.36 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (g/day) per 10 g | 0.81 | 0.40–1.61 | 0.54 |

| Protein per 10% daily calories** | 1.21 | 0.48–3.09 | 0.68 |

| Carbohydrate per 10% daily calories** | 0.82 | 0.55–1.23 | 0.34 |

| Fat per 10% daily calories** | 1.31 | 0.75–2.28 | 0.35 |

| Carbohydrate: Less than recommendations: Yes vs. No | 1.03 | 0.55–1.90 | 0.93 |

| Fat: Exceeds recommendations: Yes vs. No | 1.03 | 0.54–1.94 | 0.94 |

| Fiber: Less than recommendations: Yes vs. No | 1.12 | 0.06–20.12 | 0.94 |

| Iron: Less than recommendations: Yes vs. No*** | 2.18 | 1.01–4.70 | 0.05 |

Multivariable analysis adjusted for gender, age, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (mother’s highest educational degree)

The daily calories constituted by protein, carbohydrate or fat intake for every 10% of total daily calories.

‘Protein: Less than recommendations: Yes vs. No’ was excluded due to only 3 overweight or obese participants with ‘Yes’.

Discussion

This multi-center study suggests that there is no strong association between dietary intake of fiber, fat, carbohydrate, protein, fruits, vegetables or dairy consumption, and pediatric MS. The data are suggestive of a presence of lower iron intake among cases of pediatric MS, and this observation warrants broader investigation in longitudinal studies.

To our knowledge, no other study has previously investigated the association between these dietary components and pediatric MS. Previous work exploring associations between adult MS and diet have been of conflicting results and of varied quality of methodology. Though it may be postulated that a Western diet high in for example saturated fats may influence MS, as has been suggested by some prior work,14 the majority of studies including the only prospective study on this topic, which utilized two large cohorts of American women, have not found data supportive of this notion.15–17 However, an adult Australian case-control study of 267 cases examined any association between fat intake and risk of first clinical demyelinating event in a multi-centre case-control study, also using a food frequency questionnaire. They found a significant reduction in risk of first clinical demyelination with higher omega-3 polyunsaturated fat dietary intake, with no observed association to total fat intake or other types of fat. Though we were unable to assess omega-3 specifically, further work may wish to investigate any role of omega-3 and other micronutrients in children with demyelinating disease.18 Our results demonstrate a significantly higher weight and BMI among cases compared to controls, in support of existing evidence linking childhood obesity to an increased MS risk.4

Intake of fruit and vegetables was similarly not found to be associated with MS in a Moscow hospital-based case control study.9 This was supported by the findings of a Canadian case-control study which reported no association with intake of fruit or vegetables, but did report a negative association between MS and intake of fiber (p=0.05) and fruit juices, and a positive association between intake of calories, animal fat, pork and sweets/candy (females only).19 No associations between intake of dietary carotenoids, vitamin C and vitamin E, and risk of MS, were reported in a large American study.20

Emerging research has linked deviations in the gut microbiota to modulation of the host immune system, and though we did not find evidence to support a strong association between pediatric MS and fiber, low dietary fiber intake has previously been postulated to promote a dysbiotic gut microbiome and a low-grade systemic inflammatory state which may contribute to MS.21–22

Our data suggesting lower iron intake in pediatric MS compared to controls are interesting in light of the long discussed area of whether iron has, if any, a harmful or helpful role in MS.23 More recently, this debate garnered much attention following the emerged chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI) hypothesis of MS, suggesting the presence of harmful periventricular iron deposits in the brain.24 Difficult to reason with this notion is the subsequent report that iron depositions are similar in groups with benign and secondary progressive MS.25 Other work has also proposed that MS pathogenesis and/or clinical course may be influenced by abnormal iron depositions in the brain resulting in neurodegeneration.23–24 Furthermore, an association between shorter stature in children and iron deficiency has been suggested, but notably heights were similar across cases and controls in this study.26

We consider that both deficiency and overloading of iron may impact normal functioning of both immune and neuronal cells, and that balanced intake may be what is most important. Oligodendrocytes need high amounts of iron for the biochemical reactions involved in the maintenance of the large and complex myelin sheath.23, 27–28 Microglia provide essential components such as iron to oligodendrocytes, and in the case of mature oligendrocytes achieve this through H-ferritin, an iron transfer system used solely by oligodendocytes, in line with their heightened need.23 This may speculatively render oligodendrocytes particularly vulnerable in states of iron deficiency.27

Iron deficiency may also influence MS through its effect on immune system functioning, and may result in thymus atrophy, impaired T cell development and reduced peripheral T cells. The iron transporter NRAMP1 has also been associated with numerous autoimmune diseases, implicating iron in their development.29 Importantly, as this is a cross-sectional study we are unable to determine a temporal relationship between low iron and pediatric MS, and our findings in this regard should therefore be considered hypothesis-generating, rather than definitive. Whether a relationship between iron and MS exists, and in whichever direction of effect, will necessitate further investigation of whether altered iron levels are part of a mediating process in MS, or part of its sequelae.

The strengths of this study include the relatively large number of pediatric cases (recruited across 16 US sites) with a diverse pediatric patient population, the evaluation of different dietary components using the same methodology, and careful case ascertainment. In addition cases were enrolled early after onset (mean disease duration 11 months), and thus were unlikely to have changed their diet as there are no recommendation at this time about iron intake and MS. Limitations include that this is not a prospective study begun prior to MS onset (notably, we aimed to mitigate the impact of this by only including cases if they were within four years from symptom onset, but we cannot exclude the possibility that subjects changed their dietary habits between MS onset and the time of the study), the possibility of recall bias (we aimed to mitigate this by only asking for dietary data from the preceding week), the fact that the BKFS was not designed specifically for the assessment of all the selected nutrients and a resulting potential tendency for underestimation of nutrient intake (we therefore cannot exclude undetected small effects). The validation study had notably not defined ethnicity of the participants to confirm the study is validated for specific food groups more greatly consumed in for example Hispanic populations. However, the BKFS is designed to ask specifically about dietary components which are more common among the Hispanic populations (for example burritos, Mexican fruit drinks, etc). Further, despite the fact that control children were also seen as patients in the same medical centers, we cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias. It is possible that the conditions for which the children were seen in clinic may have affected their diets, and these control children may therefore not be representative of children in the general population. However, most controls were enrolled from general pediatric clinics and as such a selection bias is less likely. In addition, the similarities of total mean calorie intake and mean percentage intake from protein, carbohydrate and fat in both groups suggest overall a lack of bias in control enrolment.

Caloric consumption may also be underestimated in teenage age groups (specifically 18–19) due to increased alcohol and coffee intake which were not assessed in this study. We are also unable to account for potential confounding factors including other known MS risk factors such as vitamin D levels or Epstein-Barr virus infection status. Further, application of correction for multiple testing has not been formally applied, and we leave it to the reader to interpret the results in the context of the conducted analyses of a range of dietary factors.

In conclusion, in this exploratory study we observed no strong associations between most investigated dietary factors and pediatric MS, but highlight that further work elucidating any relationship between iron and MS would be of interest. Future work should aim to conduct a prospective study of pediatric MS risk, investigate the role of specific vitamins and minerals, and investigate the influence of dietary factors on disease outcomes in already established disease (for example relapse rate) using a longitudinal study design. We nonetheless hope that these results will act as reassurance to parents of pediatric MS patients, and contribute support towards current clinical practice which, at present based on the available evidence base, does not recommend any particular diet modifications (with the exception of vitamin D repletion) for children with MS.

Acknowledgments

Fundings

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health NS071463 (PI Waubant), and by the National MS Society HC 0165 (PI Casper).

We thank parents and children who have participated to this study and the study coordinators who have tirelessly enrolled subjects.

Footnotes

Authors contributions

J. Pakpoor prepared the plan of analysis, prepared the first draft of the manuscript and presented data at meetings. E. Waubant designed the study and obtained funding to support the work. She also enrolled cases and controls and participated to data analysis and edited the manuscript. B. Seminatore, and J. McDonald helped on preparing the plan of analysis. J. Graves, T. Schreiner, A. Waldman, T. Lotze, A. Belman, B. Greenberg, B. Weinstock-Guttman, G. Aaen, J.M. Tillema, J. Hart, J. Ness, Y. Harris, J. Rubin, M. Candee, L. Krupp, M. Gorman, L. Benson, M. Rodriguez, T. Chitnis, S. Mar, I. Kahn enrolled cases and controls, and edited the manuscript. S. Carmichael provided support to prepare plan of analysis and edited the manuscript. J. Rose, S. Roalstad, M. Waltz, and T.C. Casper provided support to coordinate the study, prepared plan of analysis, analyzed data and edited the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Pakpoor reports no disclosures.

Dr. Graves was supported by the Foundation for Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers and the NIH Bridging Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health programs during this work. She has been a one-time consultant for EMD-Serono.

Dr. Waubant is funded by the National MS Society, the NIH and the Race to Erase MS. She volunteers on an advisory board for a clinical trial of Novartis.

Dr. Krupp is supported by the National MS Society, NIH, Robert and Lisa Lourie Foundation, Department of Defense. She has received honoraria, consulting payments, grant support or royalties from Biogen, Medimmune, Novartis, Teva Neuroscience, Sanofi-Aventis, and EMD Serono.

Dr. Weinstock-Guttman received honoraria for serving in advisory boards and educational programs from Teva Pharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, Novartis, Accorda EMD Serono, Novartis, Genzyme and Sanofi. She also received support for research activities from the National Institutes of Health, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, National Science Foundation, Department of Defense, EMD Serono, Biogen Idec, Teva Neuroscience, Novartis, Acorda, Genzyme and the Jog for the Jake Foundation.

Dr. Tanuja Chitnis has served as a consultant for Biogen-Idec, Teva Neurosciences, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, and has received grant support from NIH, National MS Society, Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, CMSC and Merck-Serono and Novartis

Dr. Rose has research funding from Teva Neuroscience and Biogen. He is a member of the Medical Advisory Board for the DECIDE trial which is funded by Biogen and AbbiV

Dr. Casper has been supported by the National MS Society and the NIH (R01NS071463). Drs. Belman, Ness, Gorman, Lotze, Rodriguez, Aaen and James report no disclosures. Janace Hart and Timothy Simmons report no disclosures.

Dr. Carmichael reports no disclosures.

References

- 1.Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:938–952. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer-Gould A, Brara SM, Beaber BE, Zhang JL. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in multiple racial and ethnic groups. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1734–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918cc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Connor K, Weinstock-Guttman B, Carl E, Kilanowski C, Zivadinov R, Ramanathan M. Patterns of dietary and herbal supplement use by multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol. 2012;259(4):637–44. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munger KL, Bentzen J, Laursen B, et al. Childhood body mass index and multiple sclerosis risk: a long-term cohort study. Mult Scler. 2013;19(10):1323–9. doi: 10.1177/1352458513483889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon KC, Munger KL, Ascherio A. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis: epidemiology, immunology, and genetics. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25(3):246–51. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283533a7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson S, Jr, Blizzard L, Otahal P, Van der Mei I, Taylor B. Latitude is significantly associated with the prevalence of multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(10):1132–41. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2011.240432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malosse D, Perron H, Sasco A, Seigneurin JM. Correlation between milk and dairy product consumption and multiple sclerosis prevalence: a worldwide study. Neuroepidemiology. 1992;11:304–312. doi: 10.1159/000110946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghadirian P, Jain M, Ducic S, Shatenstein B, Morisset R. Nutritional factors in the aetiology of multiple sclerosis: a case-control study in Montreal, Canada. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:845– 852. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.5.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gusev E, Boiko A, Lauer K, Riise T, Deomina T. Environmental risk factors in MS: a case-control study in Moscow. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;94:386–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 Revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunsberger M, O'Malley J, Block T, Norris JC. Relative validation of Block Kids Food Screener for dietary assessment in children and adolescents. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(2):260–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/DietaryGuidelines2010.pdf

- 13.Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) :386ff. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90346-9. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490/dietary-reference-intakes-for-energy-carbohydrate-fiber-fat-fatty-acids-cholesterol-protein-and-amino-acids-macronutrients. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Swank RL. Multiple sclerosis; a correlation of its incidence with dietary fat. Am J Med Sci. 1950;220(4):421–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang SM, Willett WC, Hernan MA, Olek MK, Ascherio A. Dietary fat in relation to risk of multiple sclerosis among two large cohorts of women. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(11):1056–64. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.11.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butcher PJ. Milk consumption and multiple sclerosis–an etiological hypothesis. Med Hypoth. 1986;19:169–78. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(86)90057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berr C, Puel J, Clanet M, Ruidavets JB, Mas JL, Alperovitch A. Risk factors in multiple sclerosis: a population-based case-control study in Hautes-Pyrenees, France. Acta Neurol Scand. 1989;80:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1989.tb03841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoare S, Lithander F, van der Mei I, Ponsonby AL, Lucas R Ausimmune Investigator Group. Higher intake of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids is associated with a decreased risk of a first clinical diagnosis of central nervous system demyelination: Results from the Ausimmune Study. Mult Scler. 2016;22(7):884–92. doi: 10.1177/1352458515604380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghadirian P, Jain M, Ducic S, et al. Nutritional factors in the aetiology of multiple sclerosis: a case-control study in Montreal, Canada. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:845– 852. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.5.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang SM, Hernan MA, Olek MJ, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Intakes of carotenoids, vitamin C, and vitamin E and MS risk among two large cohorts of women. Neurology. 2001;57(1):75–80. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tremlett H, Fadrosh DW, Faruqi AA, Hart J, Roalstad S, Graves J, Spencer CM, Lynch SV, Zamvil SS, Waubant E US Network of Pediatric MS Centers. Associations between the gut microbiota and host immune markers in pediatric multiple sclerosis and controls. BMC Neurol. 2016;16(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0703-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riccio P, Rossano R. Nutrition facts in multiple sclerosis. ASN Neuro. 2015;7(1):1–20. doi: 10.1177/1759091414568185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Rensburg SJ, Kotze MJ, van Toorn R. The conundrum of iron in multiple sclerosis – time for an individualised approach. Metab Brain Dis. 2012;27(3):239–253. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9290-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zamboni P. The big idea: iron-dependent inflammation in venous disease and proposed parallels in multiple sclerosis. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:589–593. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.11.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ceccarelli A, Filippi M, Neema M, Arora A, Valsasina P, Rocca MA, Healy BC, Bakshi R. T2 hypointensity in the deep gray matter of patients with benign multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2009;15(6):678–86. doi: 10.1177/1352458509103611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soliman AT, De Sanctis V, Kalra S. Anemia and growth. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18(Suppl1):S1–5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.145038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todorich B, Pasquini JM, Garcia CI, Paez PM, Connor JR. Oligodendrocytes and myelination: the role of iron. Glia. 2009;57(5):467–78. doi: 10.1002/glia.20784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pleasure D, Abramsky O, Silberberg D, Quinn B, Parris J, Saida T. Lipid synthesis by an oligodendroglial fraction in suspension culture. Brain Res. 1977;134(2):377–82. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)91083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowlus CL. The role of iron in T cell development and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2(2):73–8. doi: 10.1016/s1568-9972(02)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]