Abstract

Excessive drinking among college students is a serious and pervasive public health problem. Although much research attention has focused on developing and evaluating evidence-based practices to address college drinking, adoption has been slow. The Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems was established in 2012 to bring together a network of institutions of higher education in Maryland to collectively address college drinking by using both individual-level and environmental-level evidence-based approaches. In this paper, the authors describe the findings of this multi-level, multi-component statewide initiative. To date, the Maryland Collaborative has succeeded in providing a forum for colleges to share knowledge and experiences, strengthen existing strategies, and engage in a variety of new activities. Administration of an annual student survey has been useful for guiding interventions as well as evaluating progress toward the Maryland Collaborative’s goal to measurably reduce high-risk drinking and its radiating consequences on student health, safety, and academic performance and on the communities surrounding college campuses. The experiences of the Maryland Collaborative exemplify real-world implementation of evidence-based approaches to reduce this serious public health problem.

Keywords: Alcohol, college students, excessive drinking, implementation, measurement, underage drinking

Introduction

Developmentally, emerging adulthood (ages 18 to 24) marks the period of greatest vulnerability for risk-taking behavior, owing in part to neurodevelopmental processes (Silveri, 2012). This heightened vulnerability, coupled with the lack of parental supervision, few boundaries on risky behavior, and plentiful and generally inexpensive opportunities to consume alcohol all increase the risk for excessive drinking during college.

Excessive drinking, the definition of which includes underage drinking (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012), has enormous social, health, and safety costs. Annually, college student alcohol use is associated with 1,825 deaths, 599,000 unintentional injuries, 696,000 assaults, 97,000 sexual assaults/date rape, and 3,360,000 students driving under the influence (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2015a). Although more recent data suggest a decline in alcohol use and related consequences among college students, possibly due to increased efforts around campus-wide alcohol prevention and intervention programming (Turner, Leno, & Keller, 2013), these young adults remain at greater risk for engaging in risky drinking behaviors than their non-college attending peers (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2014; Patrick, Terry-McElrath, Kloska, & Schulenberg, 2016). Academic consequences of heavy drinking include skipping class, poor academic performance, and discontinuous enrollment during college (Arria, Caldeira, Bugbee, Vincent, & O’Grady, 2013a; Arria et al., 2013b; Martinez, Sher, & Wood, 2008; Williams, Powell, & Wechsler, 2003). High-risk drinking patterns that persist into young adulthood can result in poorer health and delayed achievement of developmental milestones (Arria et al., 2013a; Oesterle et al., 2004; Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, Wadsworth, & Johnston, 1996). A third category of consequences are “harms to others,” including negative effects on individuals other than the drinker, ranging from having one’s sleep or studying disrupted by a roommate’s drinking to physical or unwanted sexual assault (Abbey, Zawacki, Buck, Clinton, & McAuslan, 2001; Room et al., 2010; Wechsler et al., 2002b). At the community level, alcohol-related consequences include neighborhood vandalism, excessive noise, and decreases in property values (Wechsler, Lee, Hall, Wagenaar, & Lee, 2002a).

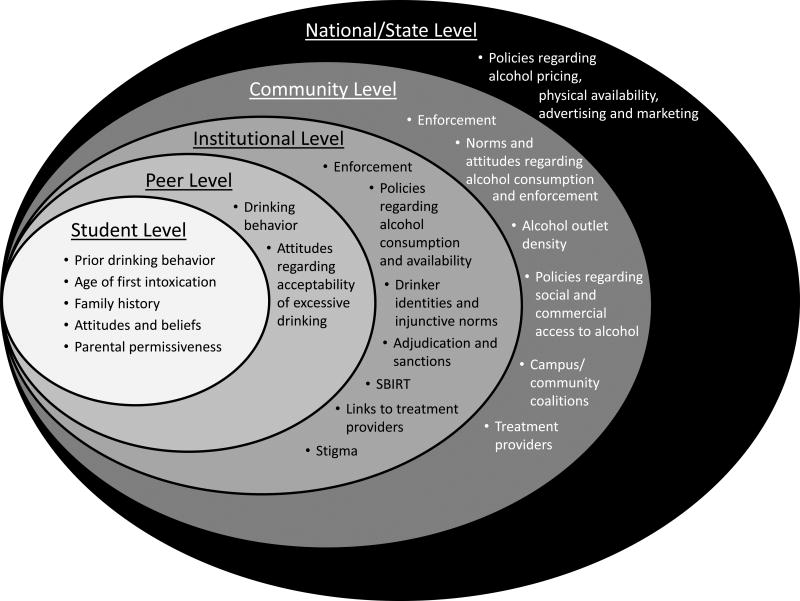

For at least the past 15 years, theory and practice have suggested that the most effective approaches to preventing and reducing excessive college drinking involve addressing community as well as individual-level factors [see Figure 1; (DeJong & Lanford, 2002)]. Because both community- or environmental-level factors and individual-level characteristics drive the problem, interventions at both levels are needed to adequately address the problem (Nelson, Winters, & Hyman, 2012; Toomey, Lenk, & Wagenaar, 2007). This is consistent with the general principles of an ecological approach to health (Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2008), which posits that interventions will be most effective if they address not only individuals but also interpersonal networks as well as organizational and environmental factors (Glanz & Bishop, 2010). The federal government’s most recent “toolkit” for colleges, in response to continued attention to the seriousness of college drinking, mirrors this approach. The College Alcohol Intervention Matrix (CollegeAIM) provides two matrices of evidence-based interventions, one for individual students, and the other at the level of the environment, including the campus community and the student population as a whole (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2015b).

Figure 1.

A socioecological framework for understanding the multiple influences on college student drinking.

However, although federal efforts have raised the profile of college drinking as a public health problem and provided guidance to colleges regarding evidence-based practices (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2015b), the adoption of new practices based on federal recommendations has been slow (Nelson, Toomey, Lenk, Erickson, & Winters, 2010), with many colleges continuing to use alcohol education, rather than evidence-based strategies to prevent and reduce excessive drinking by college students. For example, environmental approaches, which engage community stakeholders to reduce alcohol access and availability, are not common among the strategies colleges use (Wechsler, Kelley, Weitzman, SanGiovanni, & Seibring, 2000), although inclusion of them has been found to be a marker of effectiveness (Weitzman, Nelson, Lee, & Wechsler, 2004). The National College Health Improvement Program (NCHIP; 2011–2013), a notable exception, aimed to address high-risk drinking comprehensively among 32 colleges across the US. Johnson et al., (2014) have documented the NCHIP process and achievements.

Background

History of the Maryland Collaborative

In 2012 the Secretary of the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, made the reduction of excessive drinking among college students a state health priority. His vision was to establish a mechanism by which colleges could work together on this issue, align their activities with research-based evidence, and take a proactive stance to address this seemingly intractable problem. The diversity of post-secondary institutions made Maryland an ideal setting in which to establish a Collaborative and assess its effect. Maryland is similar to the national average with respect to several indicators of alcohol use, including excessive drinking (Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems, 2013a).

Dr. Sharfstein took crucial early leadership in reaching out to and convincing the president of a major private university (Johns Hopkins) and the Chancellor of the University System of Maryland, which is publicly-funded, to agree to co-chair the Governance Council of the Maryland Collaborative. Following on this initiative, and as part of the initial assessment of institutions of higher education across the state, staff reached out to leadership at each of the campuses to assess their interest in joining a statewide collaborative. Another leading college president advised Maryland Collaborative staff to form a “coalition of the willing,” namely building the Maryland Collaborative initially by inviting institutions that had expressed interest in and understood the costs of alcohol to their students’ safety and success. This president argued that developing a track record among the “willing” would make it easier to expand the Maryland Collaborative to other schools, after the Maryland Collaborative’s usefulness had been demonstrated. This is in fact what has happened, as the Maryland Collaborative has grown from 9 schools in 2013 to 15 schools in 2016 as word of its activities has spread among the higher education community in the state. The presidents of the partner schools form the Governance Council of the Maryland Collaborative. An Advisory Board, comprised of campus and community partners who were actively involved in reducing drinking on their campuses and/or surrounding communities, was also created. They provide a voice and share information with peers around the state, bring new ideas, and recommend policy changes.

Staffing the Maryland Collaborative entailed the creation of a formal partnership between public health professionals, campus leaders, and community leaders. The state of Maryland provided funding for three types of trainings and technical assistance to: (a) present science-based information to college professionals within and across colleges; (b) respond to ad hoc needs/requests of specific colleges; and (c) establish forums for cross-disciplinary discussions regarding campus- and community-level policies and activities. Two public health teams led by scientists with complementary expertise in environmental-based approaches to prevention and individual-level interventions to reduce excessive drinking, respectively, were tasked and funded to bring the latest available scientific evidence to the colleges. These teams provide operational support, training, and technical assistance to Maryland Collaborative members for the activities described below.

Understanding the Needs of the Colleges

After identifying key points of contact at all two- and four-year institutions of higher education in Maryland, staff conducted telephone interviews with the Vice President of Student Affairs or equivalent and other colleagues as deemed appropriate at 38 of the 42 degree-granting institutions in Maryland to assess what strategies they were using to address and measure high-risk drinking, what resources were available, their perceptions of the problem, and what barriers they faced in making progress (Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems, 2013a). In the inaugural year, a statewide educational conference for all interested parties was convened to explore the topic of college drinking. This day-long conference had close to 300 attendees and proved to be a great success in generating awareness around the issue.

Developing the Guide to Best Practices and the Maryland Collaborative Website

During the first year, staff authored a Guide to Best Practices summarizing the research evidence on approaches to addressing excessive drinking among college students at both the environmental and individual levels (Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems, 2013b). This Guide to Best Practices was written to be useful to non-scientists. For each topic, the evidence is summarized and tips for implementation are provided. Staff also designed a website to serve as a “one-stop shop” for Maryland Collaborative resources (www.marylandcollaborative.org), including a downloadable version of the Guide to Best Practices.

Measuring Impact: Design and Implementation of the Maryland College Alcohol Survey

As part of the initial assessment described earlier, school officials were asked how they were measuring the effect of interventions being used on their respective campuses. Where measurement was happening, different metrics were being used to assess drinking and adverse consequences, making it difficult to address problems on a statewide level. The creation of a standard measurement tool to quantify the nature and extent of the problem and understand the risk factors associated with excessive drinking at each school was indispensable for: (a) refining and targeting effective intervention strategies at salient risk factors; and (b) measuring the eventual effect of interventions on reducing excessive drinking. Each year (2014, 2015, and 2016), more than 3,300 students from the Maryland Collaborative colleges have participated in the Maryland College Alcohol Survey (MD-CAS).

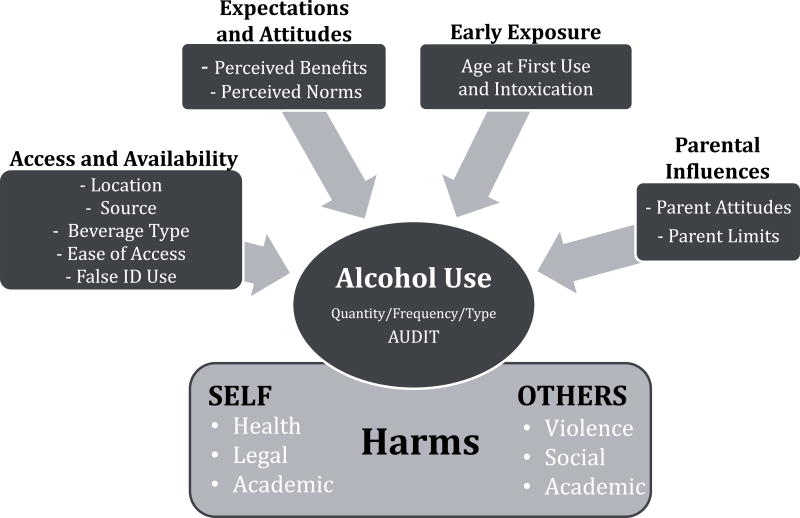

The MD-CAS is designed to measure levels of alcohol use and excessive drinking, alcohol-related consequences that drinkers experience, and harms students experience as a result of other students’ drinking. As shown in Figure 2, the initial survey included questions about the following risk factors that can influence alcohol use: (a) access and availability; (b) expectations and attitudes about alcohol use and its perceived benefits; (c) early exposure to alcohol; and (d) parental influences. The various consequences of drinking, either harms to oneself or harms to others, were adapted from national college surveys such as the CORE and Harvard College Alcohol Survey (Room et al., 2010; The Core Institute, 2013; Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeyken, & Castillo, 1994). This approach permitted the participating schools to quantify the contribution of these risk factors and target interventions. In recent annual surveys, new topics such as injunctive norms, obtaining alcohol for free, marijuana use, and academic engagement were included.

Figure 2.

Major constructs included in the Maryland College Alcohol Survey.

Students are surveyed during the weeks prior to spring break, with results tabulated in draft form by early June. Major findings are presented in aggregate for all Maryland Collaborative colleges, and aggregate data are used to understand the relationship between a particular risk factor (e.g., parental influences) and excessive drinking. A draft school-level report is provided to the primary point of contact at each college, which is typically a staff or faculty member involved in leading alcohol prevention and intervention activities on the campus, and feedback is solicited before sending the report to the President of the institution. The high level of variation among schools in the prevalence of binge drinking has provided useful evidence that excessive alcohol use is not an inevitable part of the college experience. School officials assume ownership of their own data, and additional analytic requests may be made of the Maryland Collaborative’s technical assistance team. From the reports, college officials know where they stand relative to all other schools, but school-to-school comparisons are not made public. The findings are discussed and recommendations regarding future action steps are jointly conceived. In this way, the raise awareness of a particular problem, and provide a rationale for strengthening existing strategies or implementing new ones. Following is a description of the primary strategies that have been implemented.

Strategies

Environmental-level Interventions

Identification of hot spots

To begin the process of working with the schools on environmental-level interventions, staff worked with small teams from each school to identify “hot spots” in their campus communities—places where they had reason to believe that high-risk drinking was occurring, and where they would like to intervene. Most of the schools selected off-campus parties as their starting point. Their choice was later validated by data from the MD-CAS which asks participants about their attendance at private parties and has shown that a high proportion of students drink at such events.

After hot spots had been selected, Maryland Collaborative staff referred the campus teams to the Guide to Best Practices and worked with them to select effective strategies to address them. Because environmental strategies are community-based, Maryland Collaborative staff encouraged the campus teams to work closely with local community members and, where they existed, community coalitions focused on alcohol and other drug prevention, to implement the strategies. As much as possible, Maryland Collaborative staff provided information to the campuses and community members or coalitions, and backed them to take the necessary actions.

Enforcement of existing laws

One school identified off-campus bars as its point of intervention. Staff assisted the school in monitoring law enforcement and Baltimore City Liquor Board actions with regard to one outlet in particular that had been the subject of community complaints for years with no action taken. Staff worked to connect law enforcement on- and off-campus with community organizations already seeking redress. After a police inspection found 105 of 125 patrons in the bar were underage, the Liquor Board first suspended and then revoked the bar’s license to sell alcohol (Baltimore City Paper Staff Writer, 2015). Anecdotal evidence from university officials indicated substantial reductions in alcohol transports and alcohol-related sexual assaults after implementation of these actions.

Social host ordinance

Most of the schools initially involved chose to focus on off-campus parties. On review of available evidence, staff recommended that the schools explore a civil social host ordinance. Such ordinances have been identified by CollegeAIM as a moderately effective, low-cost intervention (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2015b). Researchers have suggested that social host ordinances could be part of a successful intervention to reduce both incidence and likelihood of intoxication at off-campus parties (Saltz, Paschall, McGaffigan, & Nygaard, 2010).

Civil social host ordinances typically permit police to issue a citation on the spot to the host of an underage or loud or unruly drinking party. Some such ordinances also cite the landlord and, if the host is underage, the host’s parents. The citation generally carries a fine, ranging from $250 to $500 for the first offense, and rising from there.

Staff helped strengthen links with community members already interested in reducing the nuisances caused by loud and unruly parties. Staff provided model legislation and legal technical assistance to show how such ordinances could be written, trained college and community advocates in how to frame the issue in the news media, and assisted with the development of educational materials introducing the concept to community partners and policy makers.

Building on these educational outreach efforts, three jurisdictions in Maryland—Baltimore City, Baltimore County, and the town of Princess Anne—have so far passed new civil social host ordinances. Preliminary data from university officials suggests that police calls for service have subsequently dropped. Maryland Collaborative and college staff are awaiting data from the next round of the MD-CAS to assess if student drinking at off-campus parties has declined in response to the new ordinances.

Addressing dangerous products

High-strength “grain alcohol” is odorless, colorless, and tasteless when mixed with other beverages in party punches. National data indicate young binge drinkers are 36 times more likely to drink grain alcohol than non-binge drinkers (Binakonsky, Mitchell, Siegel, & Jernigan, 2014). In response to concerns expressed by the Governance Council, staff conducted research related to grain alcohol availability in other states, including how at least 17 other states had crafted their legislation or regulations banning grain alcohol retail sales. Fourteen university presidents signed a joint letter to the Maryland legislature, and two testified at hearings, as did staff. While one of the presidents had singly tried for years to get a ban on the highest-potency form of grain alcohol, he was unsuccessful until the Maryland Collaborative’s efforts succeeded at bringing about a state ban on the sale of alcohol at 190 proof or above (“Maximum alcohol content,” 2016).

Similarly, the presidents expressed concern about powdered alcohol. Staff worked with the presidents to educate key legislators about this form of alcohol. The Maryland legislature initially passed a one-year moratorium on the sale of powdered alcohol in 2015 and then extended it an additional two years (“Alcoholic Beverages – Sale of Powdered Alcohol – Prohibition,” 2016).

Staff have worked from existing environmental scans to develop nine scanning tools for colleges to continue to assess the risk posed to their students as the result of alcohol sales, service, and drinking patterns in a number of settings. Designed to be conducted using a smartphone, these scans include instruments specific to on-campus and off-campus outlets and tailgating, on-campus housing, off-campus parties, and special events. The colleges can use data from the scans, in conjunction with the Guide to Best Practices and CollegeAIM (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2015b), to develop action plans for addressing additional environmental risks.

Staff have also collected and reviewed all official college or university policies regarding alcohol, and rated them for clarity, accessibility, and effectiveness. The findings have been used as the basis for discussions with the member schools about how their alcohol policies might be improved. Because there has been very little academic research on effective on-campus policies, staff convened two Delphi panels—one of alcohol research experts, and the second of campus-level practitioners—who rated 47 policies drawn from the campus websites as most effective, somewhat effective, and least effective. Feedback to individual campuses on on-campus policy effectiveness reflected the ratings of these two panels.

Individual-level Interventions

Screening and brief interventions

Because individuals who engage in high-risk drinking behavior will be resistant to changing on the basis of education alone (Larimer & Cronce, 2002), trainings were offered to Maryland Collaborative school officials to identify high-risk student drinkers and directly intervene with them using motivational interviewing (MI) approaches. This approach, rather than alcohol education only, has been shown to be effective in reducing high-risk drinking among college students (Larimer & Cronce, 2002; Samson & Tanner-Smith, 2015). One of the challenges is to ensure that MI is implemented in real-world settings with the same level of fidelity as in research settings to result in measurable effects. Some college officials were engaged in MI prior to their involvement with the Maryland Collaborative and welcomed further training to refine and strengthen their capacity to deliver this intervention effectively.

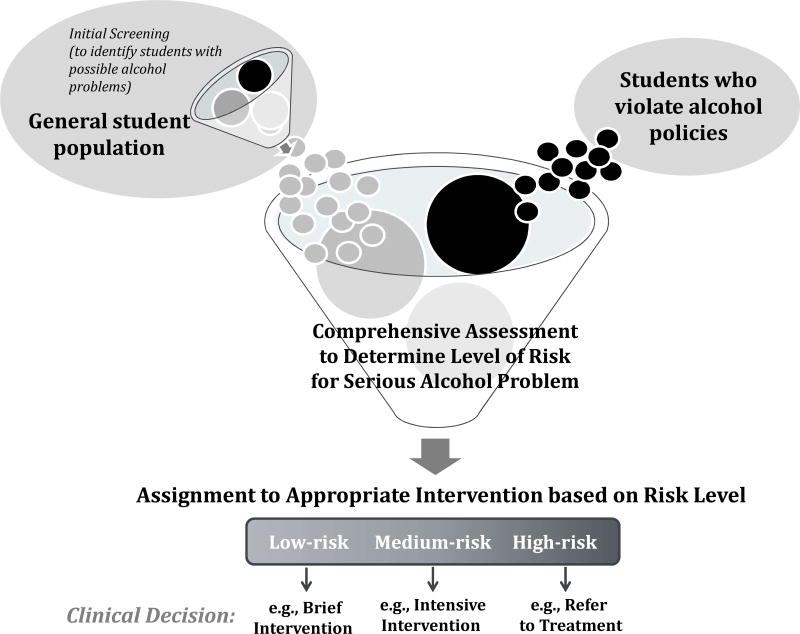

An ideal approach for implementing screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) on a college campus is shown in Figure 3. Initial screening of students with a valid instrument such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [AUDIT; (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De La Fuente, & Grant, 1993)] can identify students who have possible alcohol problems. Our initial interviews with schools found that screening typically occurs only with students who violate alcohol policies, whereas universal routine screening of the general student population is less common. While many colleges provide students with a method for self-assessment during their first year of college with programs such as AlcoholEdu (Hustad, Barnett, Borsari, & Jackson, 2010), college officials are encouraged to provide self-assessment tools for students at all ages. Second, a personalized assessment can be used to identify targets for intervention for a particular student (e.g., family history, misperceptions about the benefits of alcohol, lack of awareness about the connection between drinking frequency and sleep problems). Despite the US Preventive Task Force recommendation for screening in primary health care settings (Moyer, 2013), universal screening for alcohol use during all visits to college health centers is rare. However, it is recommended that students visiting health centers receive a comprehensive assessment of their drinking patterns and risk factors related to their drinking to guide appropriate personalized interventions instead. For students meeting criteria for serious alcohol problems, treatment might be required. Although some colleges provide substance use treatment, others who cannot are encouraged to broker relationships with community-based providers as a way of increasing their capacity to intervene with high-risk students. Increasing the number of settings in which alcohol use screenings can occur routinely (e.g., health centers, counseling centers, academic assistance centers) is encouraged so students can be referred to a central “hub” for confidential interventions. Because of the known effect of excessive drinking on academic performance, academic assistance centers could be a novel and important setting in which to screen students for high-risk drinking. A formal protocol has been developed for this purpose and plans are underway to evaluate the feasibility of this approach.

Figure 3.

An ideal model for seamless implementation of a comprehensive set of individual-level strategies.

A challenge facing health and counseling center staff with respect to MI is the lack of ability to mandate follow-up appointments for students, which could increase their effectiveness. Monitoring and follow-up has proven difficult, given the often voluntary nature of the intervention.

Several colleges were involved in campaigns to challenge normative perceptions regarding the level of excessive drinking. Research about the effectiveness of social norm campaigns has produced mixed results (Larimer & Cronce, 2007; Toomey et al., 2007). Maryland Collaborative schools have been encouraged to more specifically challenge beliefs about the social benefits of alcohol use. Researchers have shown that feeling more confident and disinhibited while drinking is rooted in expectancies rather than reality (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2002).

Design and implementation of the parent-focused website

Parent attitudes and behaviors greatly influence college student drinking behavior (Abar, Morgan, Small, & Maggs, 2012; Wood, Read, Mitchell, & Brand, 2004). High levels of parental monitoring and supervision of whereabouts and activities and less permissive attitudes related to underage drinking during high school are associated with decreased risk for excessive drinking (Abar et al., 2012; Reifman, Barnes, Dintcheff, Farrell, & Uhteg, 1998), which in turn mediates the relationship with college drinking (Arria et al., 2008). Through focus groups with parents, we learned that rather than wanting more information about the consequences of excessive drinking, their primary concern was how to have conversations about alcohol use with their grown child. Therefore, a website for parents squarely focused on communication was developed (www.collegeparentsmatter.org). It contains general tips about communication as well as conversation starters for specific high-risk situations (e.g., 21st birthday, spring break, etc.).

Discussion

Key Findings

1. Leadership matters

Having a college president who places a high priority on understanding the complexity of the causes of excessive drinking among college students and approaching it in a way that addresses that complexity is invaluable. From a practical standpoint, college presidents can bring together campus leaders around the issue and promote important discussions about which activities are needed to respond to the problem. The message of the college president permeates the campus community and facilitates and empowers campus professionals to use evidence-based practices to reduce excessive drinking.

2. Data are essential to guide action

Annual tracking of student-level information is critical to quantify the magnitude of the problem and its connection to student health, safety, and academic performance. Campus-level data can reveal unique points for increased attention—such as clarifying or increasing enforcement of policies, instituting training to detect false ID use, or targeting high-risk drinking contexts like off-campus housing or residence halls.

3. Addressing the problem at the state level has advantages

In addition to the practical advantage of economies of scale associated with resource sharing, a statewide collaborative is attractive because it demonstrates that no college is immune to the problems associated with excessive drinking and that collective action is much more effective than attempting to address problems in isolation. College officials respect and benefit from hearing other schools’ experiences, challenges, and successes, and state-level policy makers have proven more responsive to a group of schools than to a single president.

4. Direct technical assistance by experts is critical, especially when a new strategy is suggested

The guidance and assistance imparted by public health teams who staff the Maryland Collaborative to implement evidence-based strategies is essential to its success. Environmental strategies assume knowledge of laws, policies, and systems that is often not part of public health training. Building relationships to solidify partnerships with community organizations and with legal and organizing experts can assist in successful implementation. Similarly, the use of clinical experts to refine and expand the capacity for individual-level interventions has proven to be extremely useful.

Conclusions

The Maryland Collaborative exemplifies a real-world ongoing example of how state resources can be used efficiently to address a serious public health problem. The existence of high levels of variation in binge drinking prevalence illustrates that excessive drinking is not an inevitable rite of passage for all students. The Maryland Collaborative has combined public health surveillance with translational activities focused on the most effective strategies. College administrators care about providing their students with valuable and enriching academic and social experiences. Reducing excessive drinking and related problems by using evidence-based strategies can improve student outcomes, the quality of life for the entire campus community, and the viability of surrounding neighborhoods.

Table 1.

Maryland Collaborative Trainings

| Title of Training | Audience |

|---|---|

| College Drinking: What’s Happening and What Works | Higher Education Professionals |

| College Drinking, Environmental Strategies, and What Works | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Selecting Strategies and Planning Action | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Ten Steps to Policy Change | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Advancing Your Policy Work: Lessons from Cross-site Experiences | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Environmental Scans to Reduce College Drinking | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Policy and Advocacy Basics: Principles, Development and Advocacy | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Building Capacity to Advance Environmental Strategies | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Law Enforcement Training: False IDs | Law Enforcement |

| Media Advocacy | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Media Strategy Session | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Advancing Policy to Address Problems Associated With Residential Parties | Teams from member schools and local coalitionsa |

| Beyond Alcohol Violations: Strengthening Campus Systems to Connect High-risk Drinkers with SBIRT and Other Services | Health and Counseling Center Administrators and Clinicians |

| Screening and Brief Intervention with College Students: Best Practices and Future Directions | Health and Counseling Center Clinicians |

| Involving College Parents as Partners to Reduce High-Risk Drinking | Parents of College Students |

| The Impact of Substance Use on Academic Performance: The Importance of Screening for High-Risk Drinking in Academic Assistance Centers | Academic Assistant Center Staff |

| Alcohol and Athletes: What Athletic Trainers and Coaches Need to Know | Coaches and Athletic Trainers |

Usually including staff from the Office of Student Affairs, community liaisons, and campus law enforcement as well as members of local coalitions seeking to reduce and prevent underage drinking and related problems.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The Maryland Collaborative is supported by the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Behavioral Health Administration. This article was supported by the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Behavioral Health Administration and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Special thanks are extended to the Maryland Collaborative staff.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts to disclose

Contributor Information

Amelia M. Arria, Director of the Center on Young Adult Health and Development at the University of Maryland School of Public Health in College Park, Maryland (aarria@umd.edu).

David H. Jernigan, Director of the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Maryland (djernigan@jhu.edu).

References

- Abar CC, Morgan NR, Small ML, Maggs JL. Investigating associations between perceived parental alcohol-related messages and college student drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(1):71–79. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton AM, McAuslan P. Alcohol and sexual assault. Alcohol Research and Health. 2001;25(1):43–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholic Beverages – Sale of Powdered Alcohol – Prohibition, 6–326 Maryland General Assembly. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Kuhn V, Caldeira KM, O’Grady KE, Vincent KB, Wish ED. High school drinking mediates the relationship between parental monitoring and college drinking: A longitudinal analysis. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2008;3(6):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Bugbee BA, Vincent KB, O’Grady KE. The academic opportunity costs of substance use during college. College Park, MD: Center on Young Adult Health and Development; 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Winick ER, Baron RA, O’Grady KE. Discontinuous college enrollment: Associations with substance use and mental health. Psychiatric Services. 2013b;64(2):165–172. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore City Paper Staff Writer. Best flashy liquor board ruling: Closing Craig’s/Favorites Pub. 2015 Sep 15; Retrieved June 9, 2016 from http://www.citypaper.com/bob/2015/bcpnews-best-flashy-liquor-board-ruling-closing-craig-s-favorites-pub-20150915-story.html.

- Binakonsky J, Mitchell M, Siegel M, Jernigan DH. Reducing availability of extreme-strength alcohol to college students; Paper presented at the American Public Health Association.2014. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact sheet: Alcohol use and your health. 2012 Retrieved July 18, 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm.

- DeJong W, Lanford LM. A typology for campus-based alcohol prevention: Moving toward environmental management strategies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 2002;14:140–147. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs Supplement. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: A randomized controlled trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LC, Homa K, Kilmer J, Lanter P, Matzkin A, Nelson T, Provost L, Wolff K, Workman TA. Using a public health and quality improvement approach to address high-risk drinking with 32 colleges and universities. Hanover. NH: National College Health Improvement Program: Learning Collaborative on High-Risk Drinking; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2013: Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–55. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 2002;14:148–163. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JA, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is heavy drinking really associated with attrition from college? The alcohol-attrition paradox. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(3):450–456. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems. College drinking in Maryland: A status report. Center on Young Adult Health and Development, University of Maryland School of Public Health; College Park, MD: Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health; Baltimore, MD: 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Collaborative to Reduce College Drinking and Related Problems. Reducing alcohol use and related problems among college students: A guide to best practices. Center on Young Adult Health and Development, University of Maryland School of Public Health; College Park, MD: Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health; Baltimore, MD: 2013b. [Google Scholar]

- Maximum alcohol content, 6–316 Maryland General Assembly. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer VA. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159(3):210–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at U.S. colleges. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Fact sheet: College drinking. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2015a. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Planning alcohol interventions using NIAAA’s CollegeAIM (Alcohol Intervention Matrix) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2015b. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Toomey TL, Lenk KM, Erickson DJ, Winters KC. Implementation of NIAAA college drinking task force recommendations: How are colleges doing 6 years later? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(10):1687–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Winters KC, Hyman V. Preventing binge drinking on college campuses: A guide to best practices. Center City, MN: Hazelden; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Guo JIE, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Adolescent heavy episodic drinking trajectories and health in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(2):204–212. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Kloska DD, Schulenberg JE. High-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: Prevalence, frequency, and developmental change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(9):1905–1912. doi: 10.1111/acer.13164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Barnes GM, Dintcheff BA, Farrell MP, Uhteg L. Parental and peer influences on the onset of heavier drinking among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(3):311–317. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Ferris J, Laslett AM, Livingston M, Mugavin J, Wilkinson C. The drinker’s effect on the social environment: A conceptual framework for studying alcohol’s harm to others. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010;7(4):1855–1871. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior(Vol. 4th ed) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Saltz RF, Paschall MJ, McGaffigan RP, Nygaard PMO. Alcohol risk management in college settings: The safer California universities randomized trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39(6):491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson JE, Tanner-Smith EE. Single-session alcohol interventions for heavy drinking college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76(4):530–543. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57(3):289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveri MM. Adolescent brain development and underage drinking in the United States: Identifying risks of alcohol use in college populations. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2012;20(4):189–200. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2012.714642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Core Institute. CORE alcohol and drug survey: Long form. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey TL, Lenk KM, Wagenaar AC. Environmental policies to reduce college drinking: An update of research findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(2):208–219. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Leno EV, Keller A. Causes of mortality among American college students: A pilot study. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 2013;27(1):31–42. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2013.739022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeyken B, Castillo S. Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272(21):1672–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Kelley K, Weitzman ER, SanGiovanni JP, Seibring M. What colleges are doing about student binge drinking: A survey of college administrators. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):219–226. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Hall J, Wagenaar AC, Lee H. Secondhand effects of student alcohol use reported by neighbors of colleges: The role of alcohol outlets. Social Science and Medicine. 2002a;55(3):425–435. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002b;50(5):203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Nelson TF, Lee H, Wechsler H. Reducing drinking and related harms in college: evaluation of the “A Matter of Degree” program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(3):187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Powell LM, Wechsler H. Does alcohol consumption reduce human capital accumulation? Evidence from the College Alcohol Study. Applied Economics. 2003;35(10):1227–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, Brand NH. Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(1):19–30. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]