Abstract

Elopement is a dangerous behavior that is emitted by a large proportion of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Functional analysis and function-based treatments are critical in identifying maintaining reinforcers and decreasing elopement. The purpose of this review was to identify recent trends in the functional analysis and treatment of elopement, as well as determine the efficacy (standardized mean differences) of recent treatments. Over half of subjects’ elopement was maintained by social positive reinforcement, while only 25% of subjects’ elopement was maintained by social negative reinforcement. Elopement was rarely maintained by automatic reinforcement, and none of the studies in the current review evaluated treatments to address automatically maintained elopement. Functional communication training was the most common intervention regardless of function. Results are discussed in terms of clinical implications and directions for future research.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40617-017-0191-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Effect sizes, Elopement, Functional analysis, Literature review

Elopement involves leaving a designated area without permission and is common among individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs/DDs). For example, a recent survey (Anderson et al., 2012) found that about 50% of caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; n = 1200) reported having a child with ASD who had engaged in elopement at least once after the age of four. Kiely, Migdal, Vettam, and Adesman (2016) also surveyed caregivers and found that about 25% of individuals with IDDs/DDs (n = 3518) had eloped within the preceding 12 months. The incidence of elopement rose to 35% when considering individuals with dual diagnoses of IDDs/DDs and ASD.

As with other topographies of behavior, the severity of elopement (i.e., danger incurred as a result) is extremely variable. For example, one child may wander to another side of a classroom while another child may wander out of her home while caregivers are asleep. However, elopement is a uniquely dangerous behavior in that the individual is, by definition, out of reach or out of sight of caregivers. For example, 53% of caregivers surveyed by Anderson et al. (2012) reported that elopement resulted in their child becoming “missing,” or being gone long enough to cause concern, with traffic injury (65%) and drowning (24%) reported as consequences of elopement when it resulted in their child becoming missing. Even a child wandering to the other side of a room may engage in other problematic behavior that an adult may be unable to see or block (e.g., consuming edible objects).

Relative to other topographies of problem behavior, assessment of elopement involves several unique challenges. For example, in one of the earliest studies to use rigorous functional analysis (FA) methods to assess elopement, Piazza et al. (1997) explained that it is often difficult to regulate natural consequences of elopement during assessment (e.g., retrieval of the individual following the behavior). Piazza et al. also described issues related to measurement, in that behavior analysts must create opportunities to elope, at times, in situations in which a limited amount of time is available for assessment (e.g., in outpatient arrangements).

Others have reviewed the literature pertaining to elopement (Lang et al., 2009) but focused on treatment only, to the exclusion of assessment. Given the prevalence and dangers of elopement and the challenges in its assessment, as well as the ever-evolving technology of FA, the first purpose of this review was to identify methodologies in the assessment (specifically, FA) of elopement. The second purpose was to update the review by Lang et al. (2009) by evaluating the effects of treatments for elopement. Measures of effect size were calculated in order to compare the relative effectiveness of treatments across studies.

Method

Articles were identified for inclusion using a three-step process. First, the following keywords and Boolean terms were entered into three electronic databases (PsycINFO, ERIC, and PsycARTICLES): [(elopement) OR (wandering) OR (running away)] AND [(developmental disability) OR (autism) OR (mental retardation) OR (intellectual disability) OR (Down syndrome) OR (Down’s syndrome) OR (Fragile X) OR (ADHD)]. Second, the abstracts of each of the resulting studies were examined for inclusion criteria (see below). Third, the reference sections of each of the studies that met inclusion criteria were reviewed to identify articles that were not produced by the electronic search. Abstracts of those studies were also examined for inclusion criteria. If the abstract did not allow for determination for inclusion, the article was examined in its entirety.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the review, articles needed to (a) be published from 2000 to 2015, (b) include manipulation of independent variables to demonstrate a functional relation between environmental variables and elopement, and (c) include subjects with an intellectual or developmental disability. Articles that included only limited information for replication of the FA were excluded. Details on inclusion criteria are described below.

Manipulation

Similar to the review by Hanley, Iwata, and McCord (2003), studies needed to report the manipulation of an independent variable in an attempt to demonstrate a functional relation between environmental events and elopement. Thus, studies that only reported descriptive (e.g., descriptive analyses and scatterplot; Bijou, Peterson, & Ault, 1968; Touchette, MacDonald, & Langer, 1985; Vollmer, Borrero, Wright, Van Camp, & Lalli, 2001) and indirect assessments (e.g., the Functional Analysis Screening Tool; Iwata & DeLeon, 2005) were excluded, as were reviews of books and literature.

Elopement

To be considered elopement for the present review, the operational definition needed to involve a subject’s body in an area, or exceeding distance from another individual, without permission while the subject is awake. Thus, studies that examined “mind wandering” or sleepwalking were excluded.

Diagnoses of Subjects

Studies needed to include subjects with intellectual or developmental disabilities. The same diagnostic conventions that were used in the articles at the time of their publication were used in the current review. For example, although the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) no longer contains a diagnosis for Asperger’s disorder, subjects who received that diagnosis according to previous versions of the DSM (e.g., 4th ed., text rev.; DSM-IV-TR, American Psychiatric Association, 2000) were scored according to the original diagnosis (i.e., Asperger’s disorder).

Functional Analysis Procedures

Studies that met the above inclusion and exclusion criteria were scored according to several categories and along multiple dimensions.

Setting

Articles were scored according to the location of the FA as described by the authors of the studies. Articles were first read in their entirety by the first author who then developed categories according to which to score the settings of the FAs: one classroom, one clinic room, two adjoining clinic rooms, one room artificially divided into two (using a room divider), outside of a building, a hallway, and enclosed public area (a large area inside a building).

Operational Definition of Elopement and Measurement Systems

Articles were scored according to the operational definition of elopement, whether the subject (a) exceeded a given distance from the therapist, (b) left a designated area, or (c) sat/stood in a designated area. Categories were mutually exclusive.

Articles were also scored according to the measurement system (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007). This category was included because the same operational definitions (e.g., exceeding a given distance from the therapist) may lend themselves equally well to more than one measurement system (e.g., event recording for frequency or partial-interval for time spent away from the therapist). Further, one measurement system (e.g., event recording) may require additional procedural considerations (e.g., resetting the opportunity to emit the response) while another (interval-based) may not.

Event recording was scored when each instance of behavior was recorded. Partial-interval recording was scored when an occurrence of elopement at any time during a given interval was recorded. Duration recording was scored when the cumulative amount of time engaging in elopement was recorded. Latency recording was scored when the amount of time between the presentation of an antecedent and the occurrence of elopement was recorded.

FA Variations

Variations of FA were scored according to conventions described by Iwata and Dozier (2008). An FA was scored as brief when test conditions were evaluated fewer than three times each and sessions lasted no longer than 10 min (e.g., Cooper, Wacker, Sasso, Reimers, & Donn, 1990; Northup et al., 1991). A multi-element FA was scored when at least two test conditions were evaluated at least three times each and conditions rapidly alternated across sessions (e.g., Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982/1994). Technically, a brief FA is conducted in a multi-element fashion; however, the two categories were separated here because the FA literature distinguishes between procedures that expose subjects to each condition only once or twice and/or for short sessions (brief) versus at least three times and/or for longer sessions. An FA was scored as using a reversal design if at least three sessions of a test condition were conducted sequentially and were followed by at least three sessions of a control condition, in an ABAB fashion. These categories were mutually exclusive. An FA was scored as using a pairwise arrangement if control and test sessions were rapidly alternated to assess a single function (i.e., a single-function test; Iwata & Dozier, 2008).

An additional category, the latency FA, was included during which sessions were terminated after the first instance of the target behavior and the dimension of behavior that was analyzed to determine function was response latency (e.g., Thomason-Sassi, Iwata, Neidert, & Roscoe, 2011). Because latency FAs are characterized according to when sessions are terminated and not according to the experimental design, studies were scored primarily according to design (brief, multi-element, or reversal) and secondly according to whether sessions were terminated after the first instance of behavior. If a study used multiple experimental arrangements in one FA (e.g., a multi-element prior to a pairwise) and sessions were terminated following the first instance of behavior (i.e., in a latency FA) in both arrangements, “latency” was scored twice (once for the multi-element arrangement and once for the pairwise arrangement).

Method of Resetting Opportunity to Elope

One of the challenges in assessing elopement is that the opportunity to elope often needs to be reset throughout the session. An exception to this is in the case of latency FAs, during which sessions are terminated following consequence delivery for each instance of elopement (i.e., the opportunity is reset after each instance of elopement). Articles were scored as having retrieved subject after reinforcer delivery if the subject was returned to a specific place or area following or during reinforcer delivery. Articles were scored as having the therapist reposition if the therapist moved to wherever the subject had eloped to without prompting the subject back to a specific area. Fixed-time prompts to an area were scored when a prompt was delivered to the subject to remain in an area or to move to another area on a fixed-time schedule.

Functional Analysis Results and Intervention

Function(s) of Elopement

Articles were scored for “assessed” and “obtained” behavioral functions of elopement as concluded by the authors of the studies, which included attention, escape, access to tangibles or activities, and automatic reinforcement.

Intervention

For articles that included interventions, the type of intervention as described by the authors was scored. Functional communication training (FCT) was scored when the subject was taught a communicative response that was functionally equivalent to elopement. Differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO) was scored when the absence of elopement for a period of time resulted in a putative reinforcer. Noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) was scored when a putative reinforcer was presented on a time-based schedule. Blocking was scored when therapists prevented elopement from occurring by physically preventing the subject from eloping. Extinction was scored when elopement was allowed to occur but the functional reinforcer was withheld. No treatment was scored when an article did not implement a treatment following the FA. Articles were scored for each intervention that occurred. For example, if FCT was combined with extinction, “FCT plus extinction” was scored.

Effect Sizes

There is considerable debate regarding the validity of measures of effect size (e.g., standardized mean difference [SMD], regression-based techniques, overlap methods) with single-subject data (Olive & Franco, 2008; Olive & Smith, 2005; Parker, Vannest & Davis, 2011; Rakap, 2015; Wolery, Busick, Reichow, & Barton, 2010). However, we chose SMD over proposed alternatives (e.g., overlap methods) for several reasons. First, there remains precedent for calculating SMD with single-subject data (e.g., Beeson & Robey, 2006; Boyle, Samaha, Slocum, Hoffmann, & Bloom, 2016; Gierut, Morrissette, & Dickinson, 2015), and some authors continue to recommend SMD despite issues with “serial dependency” (e.g., Olive & Smith, 2005). Second, many of the overlap methods fail to assess relative magnitude of treatment effects (Wolery et al., 2010) when those effects exceed a certain minimum (i.e., a ceiling effect). In other words, two treatments may produce the same statistic even though one intervention was more effective than the other. The SMD, on the other hand, is not constrained by magnitude of treatment effect. Third, SMD yields an easily interpretable statistic, the larger of which indicates a larger effect.

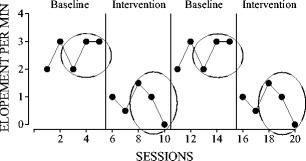

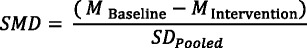

In the current review, the last three data points from each phase (and from each replication of a phase) were used in the calculation (see Fig. 1 for example). The SMD for each intervention was calculated by subtracting the mean measure (frequency, latency, duration) of elopement (from the last three sessions) during the intervention phase(s) from the mean measure of elopement (from the last three sessions) during the baseline phase(s), and dividing that difference by the pooled standard deviation of baseline and intervention phases (Fig. 2). Data were extracted from graphs using a data-extraction program (GraphClick; Boyle, Samaha, Rodewald, & Hoffmann, 2013).

Fig. 1.

Data points used for SMD calculation: last three data points from each baseline and intervention phase

Fig. 2.

Equation for SMD

Interobserver Agreement

The authors independently reviewed all articles that they identified in the initial electronic search for inclusion and independently scored all included articles according to review criteria. Agreement was high across criteria: inclusion in review (100%), diagnosis (100%), setting (100%), operational definitions (100%), measurement system (100%), FA type (92%), method of resetting (100%), and function (100%).

Scorers disagreed on the type of FA in one article (Perrin, Perrin, Hill, & DiNovi, 2008). Authors of the article stated they used a “brief FA” (one scorer accordingly scored “brief FA”); however, their FA procedures were “multi-element” according to the definition utilized in this review (the other scorer accordingly scored “multi-element FA”). Sessions in the FA lasted 5 min (as in Cooper et al., 1990 and Northup et al., 1991) but more than two sessions were conducted for each test condition. For the purpose of this review, the FA was ultimately scored as “multi-element.”

Results

The initial electronic search yielded 99 results. Excluding duplicates and those that did not meet inclusion criteria resulted in 12 studies in the current review (see Appendix for list of articles).

Journals Publishing Studies on Elopement

The majority of studies (eight) were published in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, two were published in Behavioral Interventions, and one each was published in Behavior Analysis in Practice and Topics in Early Childhood Special Education.

Functional Analysis Procedures

Subjects and Setting

Table 1 shows diagnoses of subjects and the settings in which studies were conducted, respectively. Twenty subjects participated in the 12 studies. The majority of subjects had diagnoses of Autism, followed by IDD only, IDD plus seizure disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and other DD, which included Attention Deficit Disorder and Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome. Across the 12 studies, 27 FAs were conducted, the majority of which were conducted in either one classroom (Davis et al., 2013; Gibson, Pennington, Stenhoff, & Hopper, 2010; Lang et al., 2008; Lang et al., 2010; Neidert, Iwata, Dempsey, & Thomason-Sassi, 2013) or one clinic room (Lang et al., 2008; Lehardy, Lerman, Evans, O’Connor, & LeSage, 2013; Tarbox, Wallace, & Williams, 2003). Seven FAs used two adjoining spaces: either two clinic rooms (Call, Pabico, Findley, & Valentino, 2011; Lehardy et al., 2013) or one room divided into two (Perrin et al., 2008). Two FAs were conducted outside: one at a kickball field (Stevenson, Ghezzi, & Valenton, 2015) and one in a subject’s neighborhood (Kodak, Grow, & Northup, 2004). Finally, one each was conducted in a hallway (Falcomata, Roane, Feeney, & Stephenson, 2010) or in an enclosed public area (a mall; Tarbox et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Diagnoses and settings

| Number of subjects (percentage of sample) | ||

| Diagnoses | Autism | 11 (55%) |

| ID Only | 3 (15%) | |

| ID + seizure disorder | 2 (10%) | |

| Asperger’s disorder | 2 (10%) | |

| Other DD | 2 (10%) | |

| Total | 20 | |

| Number of FAs (percentage of sample) | ||

| Settings | One classroom | 8 (30%) |

| One clinic room | 8 (30%) | |

| Two adjoining clinic rooms | 5 (19%) | |

| One room divided into two | 2 (7%) | |

| Outside | 2 (7%) | |

| Hallway | 1 (4% | |

| Enclosed public area | 1 (4%) | |

| Total | 27 |

Operational Definition of elopement and Measurement Systems

Each article was coded for one operational definition and one measurement system. The majority of studies (58%) defined elopement as “leaving a designated area,” followed by “exceeding a specific distance from a therapist” (33%), and the subject “occupying a specific area of a room” (8%). Table 2 shows the use of measurement systems for each operational definition.

Table 2.

Operational definitions, measurement systems, FA variations

| Number of studies (percentage of sample) | ||

| Operational definitions and measurement systems | Left designated area | 7 (58%) |

| Event recording | 3 | |

| Partial-interval | 2 | |

| Duration | 1 | |

| Latency | 1 | |

| Exceeded distance from therapist | 4 (33%) | |

| Event recording | 3 | |

| Partial-interval | 0 | |

| Duration | 0 | |

| Latency | 1 | |

| Sat/stood in designated area | 1 (8%) | |

| Event recording | 0 | |

| Partial-interval | 1 | |

| Duration | 0 | |

| Latency | 0 | |

| Number of FAs (percentage of sample) | ||

| FA variations | Multi-element | 25 (93%) |

| Latency | 3 | |

| Reversal | 2 (7%) | |

| Latency | 1 | |

| Brief | 1 (4%) | |

| Latency | 0 | |

| Pairwise | 1 (4%) | |

| Latency | 1 | |

| Number of studies (percentage of sample) | ||

| Method of resetting opportunity | Retrieved after SR delivery | 7 (58%) |

| Therapist reposition | 1 (8%) | |

| FT prompts to an area | 1 (8%) | |

| Not specified | 1 (8%) | |

| NA (latency FA) | 2 (17%) |

Each article was scored for only one operational definition and one measurement system. Thus, the sum of operational definitions and the sum of measurement systems are each equal to the number of studies (12)

FA functional analysis, SR reinforcer, FT fixed time, NA not applicable

FA Variations

Table 2 also shows FA variations and whether latency was used as the dimension of behavior for each variation. The total number of FAs scored was 27; however, one study (Neidert et al., 2013) used different arrangements for each of two subjects: one FA entailed a multi-element prior to a pairwise, and one FA entailed a multi-element prior to a reversal. Thus, the total number of FA arrangements (29) exceeds the total number of FAs (27).

The vast majority of FAs were conducted in multi-element arrangements. Latency FAs were conducted in three multi-element arrangements (Davis et al., 2013; Neidert et al., 2013), in one case also followed by a reversal (Neidert et al., 2013) and in one case also followed by a pairwise (Neidert et al., 2013).

Method of Resetting Opportunity to Elope

The majority of studies (Call et al., 2011; Falcomata et al., 2010; Gibson et al., 2010; Kodak et al., 2004; Lang et al., 2010; Stevenson et al., 2015; Tarbox et al., 2003) used “retrieval procedures” in which the subject was returned to a specific area during or following reinforcer delivery (Table 2). One study (Lehardy et al., 2013) entailed the therapist repositioning to where the subject eloped and one (Perrin et al., 2008) used FT prompts for the subject to remain in or move to a specific location throughout the session.

Functional Analysis Results and Intervention

Function(s) of Elopement

Escape was the most commonly evaluated function (90%), followed by attention (85%), tangible/activity (70%), and automatic reinforcement (20%). Table 3 shows the obtained functions of elopement and corresponding interventions. The denominator in the “percentage of sample” column is 20 (the number of subjects). The sum of percentages across functions does not equal 100%, as 45% of subjects’ elopement was maintained by more than one source of reinforcement.

Table 3.

Functions of elopement and interventions

| Functions and interventions | Number of subjects (percentage of sample) | SMD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ||

| Tangible/activity | 12 (60%) | ||

| Total FCT | 11 | 38.21 | 67.80 |

| FCT + blocking | 6 | 62.95 | 86.95 |

| FCT + extinction | 4 | 7.38 | 4.72 |

| FCT + response cost | 1 | 13.06 | – |

| Total NCR | 2 | 12.47 | 14.20 |

| NCR Alone | 1 | 22.51 | – |

| NCR + extinction | 1 | 2.42 | – |

| Total DRO | 2 | 2.87 | 3.98 |

| DRO alone | 1 | 0.05 | – |

| DRO + blocking | 1 | 5.68 | – |

| No treatment | 0 | NA | NA |

| Attention | 11 (55%) | ||

| Total FCT | 3 | 10.39 | 4.27 |

| FCT + blocking | 2 | 8.75 | 4.49 |

| FCT + extinction | 1 | 13.68 | – |

| Total NCR | 3 | 8.36 | 3.02 |

| NCR + blocking | 1 | 4.91 | – |

| NCR + timeout | 2 | 10.08 | 0.60 |

| No treatment | 5 | NA | NA |

| Escape | 5 (25%) | ||

| Total FCT | 1 | 2.25 | – |

| FCT + extinction | 1 | 2.25 | – |

| No treatment | 4 | NA | NA |

| Automatic reinforcement | 2 (10%) | ||

| No treatment | 2 | NA | NA |

| Unclear | 2 (10%) | ||

| Total NCR | 1 | 22.51 | – |

| NCR alone | 1 | 22.51 | – |

| No treatment | 1 | NA | NA |

SMD standardized mean difference, SD standard deviation, FCT functional communication training, NCR noncontingent reinforcement, DRO differential reinforcement of other behavior, NA not applicable

Over half of subjects’ elopement was sensitive to either positive reinforcement in the forms of access to tangibles or activities (60%) or attention (55%). One subject engaged in elopement that was maintained by attention in one setting but access to tangibles in another. Only 25% of subjects’ elopement was maintained by escape from demands, and 10% was maintained by automatic reinforcement. Regardless of function, when a treatment was implemented, FCT was the most common intervention (Davis et al., 2013; Falcomata et al., 2010; Gibson et al., 2010; Lehardy et al., 2013; Perrin et al., 2008; Stevenson et al., 2015; Tarbox et al., 2003), followed by NCR (Kodak et al., 2004; Lang et al., 2010; Perrin et al., 2008; Tarbox et al., 2003) and DRO (Call et al., 2011). None of the articles in the current review reported interventions for elopement maintained by automatic reinforcement.

Intervention

It was sometimes the case that intervention data were only reported for one function that was identified in the FA: with two subjects in Call et al. (2011) and with Victor in Lehardy et al. (2013). In addition, two studies did not include treatment evaluations, for a total of four subjects (Lang et al., 2008; Neidert et al., 2013). Finally, in one case a study evaluated the effects of more than one treatment with the same subject (Call et al.). Therefore, there is not exact correspondence between the frequency of obtained functions and the frequency of treatment evaluations.

In all cases in which the function of elopement was identified, FCT was the most utilized intervention (tied with NCR for elopement maintained by attention; Table 3). Further, FCT was always combined with another intervention, such as response blocking (Lehardy et al., 2013; Stevenson et al., 2015; Tarbox et al., 2003), extinction (Davis et al., 2013; Falcomata et al., 2010; Perrin et al., 2008), or response cost (Gibson et al., 2010). The next most commonly used intervention was NCR (Kodak et al., 2004; Lang et al., 2010; Perrin et al., 2008; Tarbox et al., 2003), which was also often combined with another intervention, such as response blocking (Lang et al., 2010), extinction (Lang et al., 2010), or timeout (Kodak et al., 2004; Tarbox et al., 2003), although in one case it was implemented in isolation (Perrin et al., 2008). Finally, DRO was the least frequently implemented and in only one study (Call et al., 2011) on a comparison of DRO alone versus in combination with response blocking.

Effect Sizes

For all but one treatment evaluation (DRO without blocking; Call et al., 2011), the authors of studies in this review concluded their interventions were clinically effective (produced meaningful decreases in elopement). We calculated SMD in order to compare the relative effectiveness of treatments within and across functions. Cohen (1988) suggested that d statistics of 0.2, 0.5., and 0.8 represent small, medium, and large effects, respectively. However, these benchmarks are not appropriate for data collected within single-subject designs (Gieret & Morrisette, 2011; Wolery et al., 2010), as SMD tend to be inflated with single-subject data. Instead, we partitioned effect sizes in the current review into three groups after first excluding major outliers (which resulted in the exclusion of three data points). We also excluded an effect size of 0.05 (Call et al., 2011) as a “no effect,” as the authors of that study concluded it was not effective. We next conducted a k-cluster analysis (Gierut et al., 2015) to partition the remaining 15 effect sizes into three groups (small, medium, and large; Table 4). The majority of effect sizes in the current review were situated in the lowest of the three designated groups. It is important to note that this analysis simply organized the effect sizes calculated in this review into three groups.

Table 4.

Results of k-means cluster analysis

| Magnitude of effect | Number of interventions | SMD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | ||

| Small | 9 | 5.15 | 2.25–7.89 |

| Medium | 5 | 11.77 | 9.66–13.68 |

| Large | 1 | 22.51 | NA |

Four effect sizes were excluded from k-means cluster analysis (three outliers and one non-effect)

SMD standardized mean difference, NA not applicable

For functions for which at least two interventions were evaluated (attention, access to tangible/activity; Table 3), FCT was the most effective (Call et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2013; Falcomata et al., 2010; Gibson et al., 2010; Kodak et al., 2004; Lang et al., 2010; Lehardy et al., 2013; Perrin et al., 2008; Stevenson et al., 2015; Tarbox et al., 2003). The effects of additional interventions (response blocking, extinction, response cost, timeout) when combined with FCT, NCR, and DRO were inconsistent across functions. For example, FCT plus response blocking (Lehardy et al., 2013; Stevenson et al., 2015; Tarbox et al., 2003) was more effective than FCT plus extinction (Falcomata et al., 2010; Perrin et al., 2008) for elopement maintained by access to tangibles, but the opposite was true with elopement maintained by attention (Davis et al., 2013; Lehardy et al., 2013; Stevenson et al., 2015).

Discussion

Elopement is a dangerous and relatively common behavior emitted by individuals with IDDs/DDs. Elopement can be challenging to assess and treat due to the nature of the behavior itself, in that, by definition, the individual becomes physically out of reach of a therapist. Elopement may pose challenges for practitioners who are trained in the assessment of topographies of problem behavior that generally do not result in an increased physical distance between an individual and a therapist (e.g., aggression, property destruction, self-injury). The purpose of this review was to serve as a resource for practitioners regarding recent methodologies in the functional analysis and treatment of elopement and to identify areas for future research. Future reviews of literature may be conducted that focus on other methods of functional assessment, such as indirect and descriptive formats, given their prevalence in applied settings. Some clinical implications and areas for research based on the current review are discussed below.

Operational Definitions and Measurement

The majority (91%) of FAs utilized definitions that entailed discrete responses (Table 2): leaving a designated area and exceeding a given distance from a therapist. Surprisingly few of these studies (only two of 11) used latency as their measurement system (Davis et al., 2013; Neidert et al., 2013); the majority used frequency recording. Given the dangerousness of elopement, it may be useful to further explore latency as a measure of response strength (Thomason-Sassi et al., 2011), which would allow for fewer opportunities for elopement to occur. Partial-interval and duration measures were used less often but may be useful in cases in which the definition for elopement rests on an individual occupying a specific area. For example, Gibson et al. (2010) used partial-interval recording when the definition of elopement was defined as “having (a) all of one’s body within the inner-most concentric circle on the carpet, (b) all of one’s body off of the carpet, or (c) all of one’s body over the letter to the left or right of the assigned letter,” on an alphabet carpet in the classroom (p. 217).

Methods of Resetting

If a measurement system consists of event recording or latency, the opportunity for a subject to elope needs to be “reset.” For example, if “exceeding a given distance from a therapist (e.g., 10 ft)” was the operational definition with “frequency recording” as the measurement system, the therapist needs to reset the subject and the therapist following each instance of elopement such that the distance between them is less than 10 ft in order for the response (exceeding 10 ft from the therapist) to reoccur. If the opportunity were not reset, the subject might elope and remain at a distance greater than 10 ft from the therapist during the entire session. The measurement system would reflect one instance of elopement, even though the individual exceeded 10 ft from the therapist the entire time. This issue is not unique to elopement (e.g., “flopping to the ground” carries the same considerations), but in the case of flopping to the ground, the subject is physically within reach of the therapist, and thus resetting the opportunity may be less challenging.

The majority of articles’ procedures (Call et al., 2011; Falcomata et al., 2010; Gibson et al., 2010; Kodak et al., 2004; Lang et al., 2010; Stevenson et al., 2015; Tarbox et al., 2003) entailed retrieving the subject following the delivery of the reinforcer. For example, Call et al. (2011) used a “retrieval procedure” in which the subject “was returned to the location from which he had eloped after 20 s” (p. 904). Reinforcers were delivered immediately following elopement, but the subject was returned following 20 s of the response regardless of the condition. Kodak et al. (2004) similarly retrieved subjects following elopement but ensured that in non-attention conditions the subject was retrieved with the “minimal amount of physical contact necessary to return her” (p. 230).

Retrieval procedures necessarily involve the delivery of attention, which may make it difficult to conclude that elopement is maintained by a consequence other than attention. In other words, the delivery of attention (in the form of a retrieval) in a non-attention condition (e.g., escape) makes it impossible to determine which stimulus change (attention or escape) is the reinforcer for elopement. In fact, some researchers (e.g., Davis et al., 2013) suggest exploring methods that do not require retrieval procedures at all; for example, with latency recording systems. Tarbox et al. (2003) attempted to circumvent the confounding of attention delivery during retrieval by delivering prompts every 30 s to walk next to the therapist and by arranging a confederate therapist to block attempts to leave the clinical area. In this case, attention was programmed to occur in all conditions (on an FT schedule), and unprogrammed attention (e.g., blocking an exit) never needed to be delivered by the therapist in the test conditions. Lehardy et al. (2013) directly addressed this issue by comparing results of two FAs: one that entailed retrieval (“two-room FA”) and one that did not (“single-room” FA). The two-room FA consisted of two adjoining rooms, and the subject was returned to the room from which he/she eloped following reinforcer delivery. The single-room FA consisted of a single room divided in half with a piece of tape, and the therapist moved to the side of the room to which the subject eloped following reinforcer delivery. For each subject, the two types of FAs identified the same functions, which suggests that the single-room FA may be a viable option in cases in which only room is available and/or there may not be enough therapists to block attempts at leaving the clinical area.

FA Results and Treatments

One somewhat surprising result of this review is that although escape was the most commonly assessed function, it was the least commonly obtained social function (Table 3). The direct, immediate consequence of elopement is increased physical distance between an individual and the environment from which he or she eloped (i.e., physical “escape”). However, this does not mean that the reinforcer for elopement is escape itself—in fact, among the subjects that participated in the studies in the current review, the most common function of elopement was access to tangibles and activities, followed closely by attention.

In cases in which an “access to tangible/activity” function is suspected, collecting descriptive data (e.g., ABC) prior to an FA to determine the items/activities to which an individual elopes may be especially useful as the tangibles/activities may be extremely idiosyncratic. For example, Falcomata et al. (2010) assessed and treated a subject’s elopement that was maintained by access to stereotypy in the form of “door play.” The authors reported undifferentiated FA results prior to evaluating the door-play hypothesis.

Differential reinforcement in the form of FCT was the most common intervention for elopement, followed by NCR and DRO. For tangible and attention functions, FCT was combined more often with blocking than with extinction; FCT was only used once for elopement maintained by escape, and in that case it was combined with extinction. Treating elopement with extinction but without blocking requires that (a) the individual can still elope but (b) will not contact the functional reinforcer. With elopement maintained by access to tangibles, this may be difficult unless a therapist is available to block access to the items when the individual reaches them. With elopement maintained by attention, this may also be difficult during acquisition of a communication response, as a therapist needs to be in close proximity to the individual in order to prompt the individual to emit the response. This issue is not fundamentally different from other topographies of behavior maintained by attention, in that a prompter necessarily needs to deliver attention (albeit as unobtrusively as possible). However, attention-maintained elopement may be specifically reinforced by a decreasing proximity between the individual and a therapist. In other words, a prompting therapist maintaining proximity to an individual may inadvertently reinforce attention-maintained elopement. In such cases, it may be useful to enhance the difference between the magnitude of the attention delivered by the prompting therapist and the attention delivered by the therapist following a communicative response.

It should be noted that of the two cases in which elopement was found to be maintained by automatic reinforcement (both subjects in Neidert et al., 2013), neither included treatment evaluations. Treating automatically reinforced behavior, regardless of topography, carries unique challenges (Rapp, 2008; Rapp & Vollmer, 2005). Therefore, a future area of research may focus on the treatment of automatically maintained elopement.

With the limited number of data sets in the current review, conclusions regarding effectiveness of treatments should be drawn tenuously. Interventions consisting of FCT were more effective than those consisting of NCR among tangible/activity and attention functions (Table 3). Regarding combinations of interventions with FCT, there was not a consistent relation between FCT with blocking versus FCT with extinction: FCT with blocking was more effective when the function was tangible/activity (Lehardy et al., 2013; Tarbox et al., 2003), but FCT with extinction was more effective when the function was attention (Davis et al., 2013). Only one treatment evaluation addressed an escape function (Perrin et al., 2008), and the SMD was the lowest relative to nearly all other treatment evaluations.

Conclusions

Elopement is a dangerous behavior that is emitted by a large proportion of individuals with IDDs/DDs. Functional analysis and function-based treatments are critical in identifying maintaining reinforcers and decreasing elopement, generally through increasing an appropriate, functionally equivalent, alternative response. Special considerations need to be taken when assessing and treating elopement, specifically regarding measurement systems and resetting the opportunity for the response to occur. Although physical escape is a direct consequence of elopement, the reinforcer for the subjects in this review was more often access to a positive reinforcer (either tangible or attention). Proportionally fewer treatment evaluations have been conducted recently with escape- and automatically maintained elopement, which are two areas for future research.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 111 kb)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Both authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Studies with Human Participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40617-017-0191-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, Law JK, Daniels A, Rice C, Mandell DS, Hagopian L, Law P. Occurrence and family impact of elopement in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;130:870–877. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeson PM, Robey RR. Evaluating single-subject treatment research: lessons learned from the aphasia literature. Neuropsychology Review. 2006;16:161–169. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9013-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijou SW, Peterson RF, Ault MH. A method to integrate descriptive and experimental field studies at the level of data and empirical concepts. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:175–191. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M, Samaha AL, Rodewald A, Hoffmann AN. Evaluation of the reliability and validity of GraphClick as a data extraction program. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29:1023–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MA, Samaha AL, Slocum TA, Hoffmann AN, Bloom SE. A human-operant investigation of preceding- and following-schedule behavioral contrast. The Psychological Record. 2016;66:381–394. doi: 10.1007/s40732-016-0179-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Call NA, Pabico RS, Findley AJ, Valentino AL. Differential reinforcement with and without blocking as treatment for elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:903–907. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. 2. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LJ, Wacker DP, Sasso GM, Reimers TM, Donn LK. Using parents as therapists to evaluate appropriate behavior of their children: application to a tertiary diagnostic clinic. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1990;23:285–296. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1990.23-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TN, Durand S, Bankhead J, Strickland E, Blenden K, Dacus S, et al. Brief report: latency functional analysis of elopement. Behavioral Interventions. 2013;28:251–259. doi: 10.1002/bin.1363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falcomata TS, Roane HS, Feeney BJ, Stephenson KM. Assessment and treatment of elopement maintained by access to stereotypy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:513–517. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JL, Pennington RC, Stenhoff DM, Hopper JS. Using desktop videoconferencing to deliver interventions to a preschool student with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2010;29(4):214–225. doi: 10.1177/0271121409352873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gierut JA, Morrisette ML, Dickinson SL. Effect size for single-subject design in phonological treatment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2015;58:1468–1481. doi: 10.1044/2015_JSLHR-S-14-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, McCord BE. Functional analysis of problem behavior: a review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:147–185. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B, DeLeon I. The functional analysis screening tool. Gainesville, FL: The Florida Center on Self-Injury, University of Florida; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Dorsey MF, Slifer KJ, Bauman KE, Richman GS. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Dozier CL. Clinical application of functional analysis methodology. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1(1):3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03391714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely B, Migdal TR, Vettam S, Adesman A. Prevalence and correlates of elopement in a nationally representative sample of children with developmental disabilities in the United States. PloS One. 2016;11(2):e0148337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodak T, Grow L, Northup J. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement for a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:229–232. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, Davis T, O’Rielly M, Machalicek W, Rispoli M, Sigafoos J, et al. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement across two school settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:113–118. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, O’Reilly M, Machalicek W, Lancioni G, Rispoli M, Chan JM. A preliminary comparison of functional analysis results when conducted in contrived versus natural settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:441–445. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, Rispoli M, Machalicek W, White PJ, Kang S, Pierce N, et al. Treatment of elopement in individuals with developmental disabilities: a systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30:670–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehardy RK, Lerman DC, Evans LM, O’Connor A, LeSage DL. A simplified methodology for identifying the function of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:256–270. doi: 10.1002/jaba.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidert PL, Iwata BA, Dempsey CM, Thomason-Sassi JL. Latency of response during the functional analysis of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:312–316. doi: 10.1002/jaba.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northup J, Wacker D, Sasso G, Steege M, Cigrand K, Cook J, DeRaad A. A brief functional analysis of aggressive and alternative behavior in an outclinic setting. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:509–522. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive ML, Franco JH. (Effect) size matters: and so does the calculation. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2008;9(1):5–10. doi: 10.1037/h0100642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olive ML, Smith BW. Effect size calculations and single subject designs. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology. 2005;25(2–3):313–324. doi: 10.1080/0144341042000301238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RI, Vannest KJ, Davis JL. Effect size in single-case research: a review of nine nonoverlap techniques. Behavior Modification. 2011;35:303–322. doi: 10.1177/0145445511399147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin CJ, Perrin SH, Hill EA, DiNovi K. Brief functional analysis and treatment of elopement in preschoolers with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2008;23:87–95. doi: 10.1002/bin.256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza CC, Hanley GP, Bowman LG, Ruyter JM, Lindauer SE, Saiontz DM. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:653–672. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakap S. Effect sizes as result interpretation aids in single-subject experimental research: description and application of four nonoverlap methods. British Journal of Special Education. 2015;42:11–33. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp JT. Conjugate reinforcement: a brief review and suggestions for applications to the assessment of automatically reinforced behavior. Behavioral Interventions. 2008;23:113–136. doi: 10.1002/bin.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp JT, Vollmer TR. Stereotypy I: a review of behavioral assessment and treatment. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;26:527–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson MT, Ghezzi PM, Valenton KG. FCT and delay fading for elopement with a child with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;9(2):169–173. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0089-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox RSF, Wallace MD, Williams L. Assessment and treatment of elopement: a replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:239–244. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason-Sassi JL, Iwata BA, Neidert PL, Roscoe EM. Response latency as an index of response strength during functional analyses of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:51–67. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchette PE, MacDonald RF, Langer SN. A scatterplot for identifying stimulus control of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18:343–351. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1985.18-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer TR, Borrero JC, Wright CS, Van Camp C, Lalli JS. Identifying possible contingencies during descriptive analyses of severe behavior disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:269–287. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolery M, Busick M, Reichow B, Barton EE. Comparison of overlap methods for quantitatively synthesizing single-subject data. The Journal of Special Education. 2010;44:18–28. doi: 10.1177/0022466908328009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 111 kb)