Abstract

There is an increasing appreciation for the role of the human Y chromosome in phenotypic differences between the sexes in health and disease. Previous studies have shown that genetic variation within the Y chromosome is associated with cholesterol levels, which is an established risk factor for atherosclerosis, the underlying cause of coronary artery disease (CAD), a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. However, the exact mechanism and potential genes implicated are still unidentified. To date, Y chromosome-linked long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are poorly characterized and the potential link between these new regulatory RNA molecules and hepatic function in men has not been investigated. Advanced technologies of lncRNA subcellular localization and silencing were used to identify a novel intergenic Y-linked lncRNA, named lnc-KDM5D-4, and investigate its role in fatty liver-associated atherosclerosis. We found that lnc-KDM5D-4 is retained within the nucleus in hepatocytes. Its knockdown leads to changes in genes leading to increased lipid droplets formation in hepatocytes resulting in a downstream effect contributing to the chronic inflammatory process that underpin CAD. Our findings provide the first evidence for the implication of lnc-KDM5D-4 in key processes related to fatty liver and cellular inflammation associated with atherosclerosis and CAD in men.

Introduction

The human Y chromosome is best known for its key role in spermatogenesis and testicular development1. It is becoming increasingly clear that the biological functions of the Y chromosome transcend the male fertility and reproduction2, with associations between genetic variation within the male-specific region of the Y chromosome (MSY) and complex polygenic phenotypes including blood pressure3, circulating cholesterol levels4, and coronary artery disease (CAD)2,5 being reported. The mechanisms of these associations are not entirely clear although it appears that they are (at least in part) mediated by the expression of MSY genes in the target cells and tissues6. To date, over 200 Y-linked genes have been identified and those that encode Y proteins have been well-characterised7. However, MSY harbours not only 27 protein-coding genes but also a number of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) – important new regulatory molecules implicated in cardiovascular health8 and disease9. So far, there is no data on Y chromosome-linked lncRNAs in relation to any human phenotypes. To this end, we sought to investigate Y-linked long intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs) - the largest class within the lncRNA group10 - in relation to phenotypes of relevance to CAD such as fatty liver-associated atherosclerosis.

Here, we studied for the first time eleven novel Y-linked lincRNAs by real-time PCR gene expression analysis in the human hepatoma HepG2 male cell line, an in vitro model system used in previous studies on liver steatosis and CAD11–14. We also investigated the expression of a novel intergenic Y-linked lincRNA, named lnc-KDM5D-4, across 21 normal tissue types. Utilising advanced technologies of lncRNA subcellular localization and silencing, we further characterized lnc-KDM5D-4 within HepG2 cells, and investigated the effects of its knockdown on atherosclerosis-related genes in these cells. Throughout the text, ‘lnc-KDM5D-4′ refers to the long non-coding RNA gene, and ‘lnc-KDM5D-4:1′ refers to the long non-coding RNA transcript.

Materials and Methods

Primer design

The human lincRNA catalogues15,16 were used to select Y-specific lincRNA genes based on their expression in tissues relevant to the liver and CAD, such as heart, liver and white blood cells (WBCs) (Supplementary Materials and Methods). Primers for SYBR® Green-based real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) gene expression analysis were designed using the free online software Primer-BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) following the recommendations for probe melting temperature (Tm) values, GC content, and amplicon length provided by Thornton & Basu17. All the primers for lincRNAs were designed from the DNA template sequence annotated on LNCipedia, the database for human lncRNA genes and transcripts18. Primer sequences are available in Supplementary Table S1.

HepG2 cell culture and treatments

The human hepatoma cell line, HepG2, obtained by the Charchar Laboratory, was grown as a monolayer culture in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, 1X) (Gibco®, Life Technologies™) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat inactivated foetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) (Gibco®, Life Technologies™), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco®, Life Technologies™) and were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% (v/v) CO2 in the air. The HepG2 cell model of palmitate-induced steatosis and insulin-resistance were developed as previously described19 (Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Human tissue RNA panel

The Human Tissue RNA Panel was obtained from Ambion® FirstChoice®Human. Total RNA Survey Panel which consists of 10 µg pools of total RNA (stored in 1 mmol/L of sodium citrate) from 20 different normal, human tissues including adipose, bladder, brain, cervix, colon, esophagus, heart, kidney, liver, lung, ovary, placenta, prostate, skeletal muscle, small intestine, spleen, testes, thymus, thyroid, and trachea. Each pool is comprised of RNA from 3 tissue donors (with at least 1 male donor per tissue except for the cervix, placenta, and ovary RNA sample pools) and underwent a stringent DNase treatment. After storage at −80 °C on arrival, RNA samples were thawed at 37 °C then placed on ice prior use as recommended by the manufacturer’s instructions.

Blood collection

To study the expression of lincRNAs expressed in leucocytes in men, five healthy male volunteers (positive control group) and two healthy females (negative control group), between 18–50 years old were recruited at the Federation University Australia (Mount Helen campus). Participants were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: current non-smokers, free of recent surgery, ambulatory aids, and acute joint injury, free of underlying medical conditions such as heart disease, un-medicated hypertension and respiratory disorders in order to avoid skewing the results. Participants’ blood was withdrawn in Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) blood collection tubes (tubes commonly used in routine haematology and furnished by the phlebotomist) by a qualified phlebotomist at Mount Helen campus. Then, blood samples were immediately stored on ice and total RNA was purified within an hour of collection to preserve the RNA integrity. This study was approved by the Federation University Ethics Committee at Mount Helen campus and carried out in accordance with Federation University relevant guideline and regulations. All the subjects gave informed consent [Ethics Project Number: B13-020].

Oil Red O cell staining

To confirm steatosis induced by palmitate in HepG2 cells, cellular lipid droplets were stained using Oil Red O (ORO) from Hepatic Lipid Accumulation/Steatosis Assay (abcam®) (Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Protein extraction and Western Blot analysis

Total cellular protein from HepG2 cells treated with insulin over 48 h was isolated by scraping the cells with Pierce® RIPA buffer. A total soluble protein (50 μg) was resolved on a 4–15% SDS-PAGE gradient gel (BIORAD®) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Total RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Ambion®). Total RNA was resuspended in 50 µL RNase-free water followed by a column DNase treatment (1 µL per RNA sample) using Recombinant DNase I (Ambion®, Applied Biosystem®) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA yield and purity were measured by absorbance using a NanoDrop™ 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific®, Australia). The ratio (A260 nm/A280 nm) of ~2.0 was accepted as “pure” for RNA. Finally, RNA samples were stored at −80 °C until use.

Synthesis of cDNA and real-time PCR

RNA (2 µg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the High Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies®). Real-time PCR was assessed in triplicate and carried out using SYBR® Green (Bioline®) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were analysed using the 2-delta delta CT method20. CT results were normalised with two housekeeping genes, ACTB (or GAPDH) and UBC (Supplementary Materials and Methods).

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA FISH)

RNA FISH was performed using the advanced QuantiGene® ViewRNA ISH Cell Assay (Affymetrix®). The permeabilisation procedure was amended and 1% glacial acetic acid was added to the fixation solution to detect nuclear RNAs21, then the RNA FISH assay from Four-Chambered Dish Format protocol was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Nuclear and Cytoplasmic RNA fraction isolations

Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA fractions were isolated separately from confluent cells using the Cytoplasmic & Nuclear RNA Purification Assay (Norgen Biotek Corp.®, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both RNA fractions, nuclear and cytoplasmic, were resuspended in 50 µL RNase-free water followed by a column DNase treatment (1 µL per 1000 ng of RNA) using the Recombinant DNase I (Ambion®, Applied Biosystem®) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA yield and purity were measured by absorbance using a NanoDrop™ 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific®, Australia). The ratio (A260 nm/A280 nm) of ~2.0 was accepted as “pure” for RNA. Finally, the RNA samples were stored at −80 °C until use.

Cell transfection and lncRNA knockdown

Advanced antisense oligonucleotides (AOs) Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA™) longRNA GapmeRs - a class of high-affinity RNA analogues that exhibit high thermal stability when hybridized to a complementary DNA or RNA strand - were used to silence lnc-KDM5D-4. Antisense LNA™ longRNA GapmeRs were custom designed (except for the control GapmeR ‘Negative control A’) and synthesized by Exiqon®. Three different GapmeRs targeting three different sites of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 RNA were used following the Exiqon’s recommendations. The transfection of the following GapmeRs, lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_1 (Product sequence 5′-3′: GAGATGAAGCGGAATT), lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_2 (Product sequence 5′-3′: CTTACTTTAGACTTC), lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_3 (Product sequence 5′-3′: ACGTAAAATAGGATTA), and Negative control A (Product sequence 5′-3′: AACACGTCTATACGC) were performed using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific®) following Exiqon manufacturer’s recommendations as well as those for knockdown of lncRNA and AOs provided by Integrated DNA Technologies®’s webinars on www.youtube.com/user/idtdnabio. HepG2 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of ~2 × 105/mL and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% HI-FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) until the cells reached ~70% confluence. Then, the cells were transfected with 10 nmol/L of AO in Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent. After 48 h, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent followed by a RNA clean-up step using miRNeasy kit (Qiagen®). Then, the knockdown was confirmed by real-time PCR.

Reverse transcription and Atherosclerosis RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array

The Human Atherosclerosis RT2 Profiler PCR Array (PAHS-038ZE) from SA Biosciences (Qiagen®; Catalogue No. 330231) was performed following the manufacturer’s recommendations (Supplementary Materials and Methods). Then, the human tissue-specific network webserver GIANT22 was used to generate the potential tissue-specific functional interactions between the atherosclerosis-relevant genes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed using Prism (GraphPad Software). Data were analysed using a Student’s unpaired t-test to test significance of data comparisons between cell treatments, with p-values < 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Results

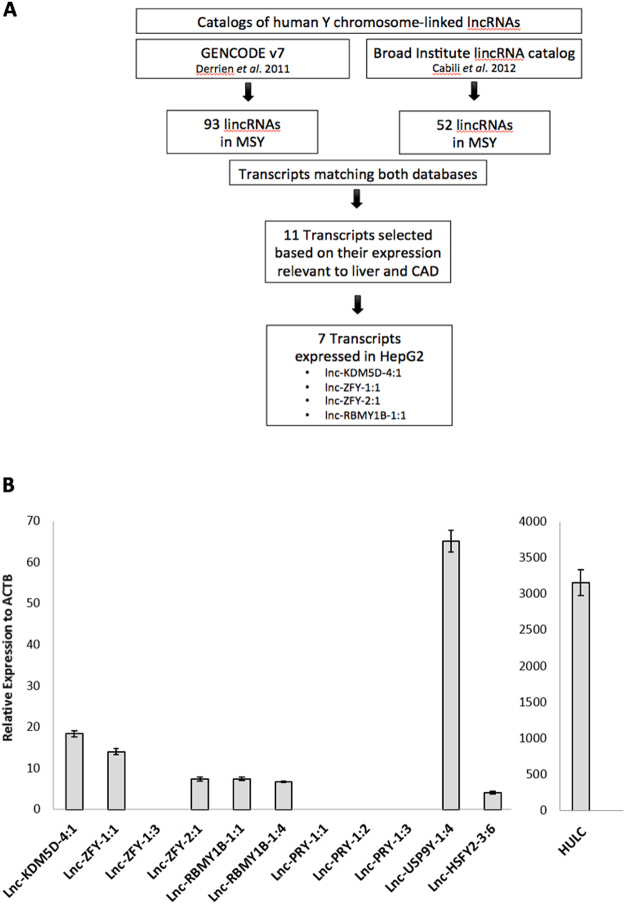

A survey of the expression of novel Y chromosome-linked lincRNAs in HepG2 cells

Using human lncRNA reference catalogues15,16 which include the Y chromosome, we identified 11 candidate MSY lincRNA transcripts and measured their expression in the human hepatoma HepG2 cell line. Seven MSY lincRNA transcripts such as lnc-KDM5D-4:1, lnc-ZFY-1:1, lnc-ZFY-2:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:4, lnc-USP9Y-1:4, and lnc-HSFY2-3:6 were found to be expressed in the HepG2 cells (Fig. 1A,B). Their average abundance was significantly lower than that of lncRNA HULC (Hepatocellular carcinoma up-regulated long non-coding RNA) which was used as a positive control23.

Figure 1.

Identification of Y chromosome lincRNAs in HepG2 cells. (A) Steps followed in the identification process of Y-specific lincRNAs. (B) Y-specific lincRNA real-time PCR analysis. Lnc-KDM5D-4:1, lnc-ZFY-1:1, lnc-ZFY-1:3, lnc-ZFY-2:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:4, lnc-PRY-1:1, lnc-PRY-1:2, lnc-PRY-1:3, lnc-USP9Y-1:4, and lnc-HSFY2-3:6 normalised expression values with respective S.E.M. relative to actin beta (ACTB) housekeeping gene. HULC – a lincRNA with confirmed up-regulation in HepG2 cells - used as a positive control (n = 3).

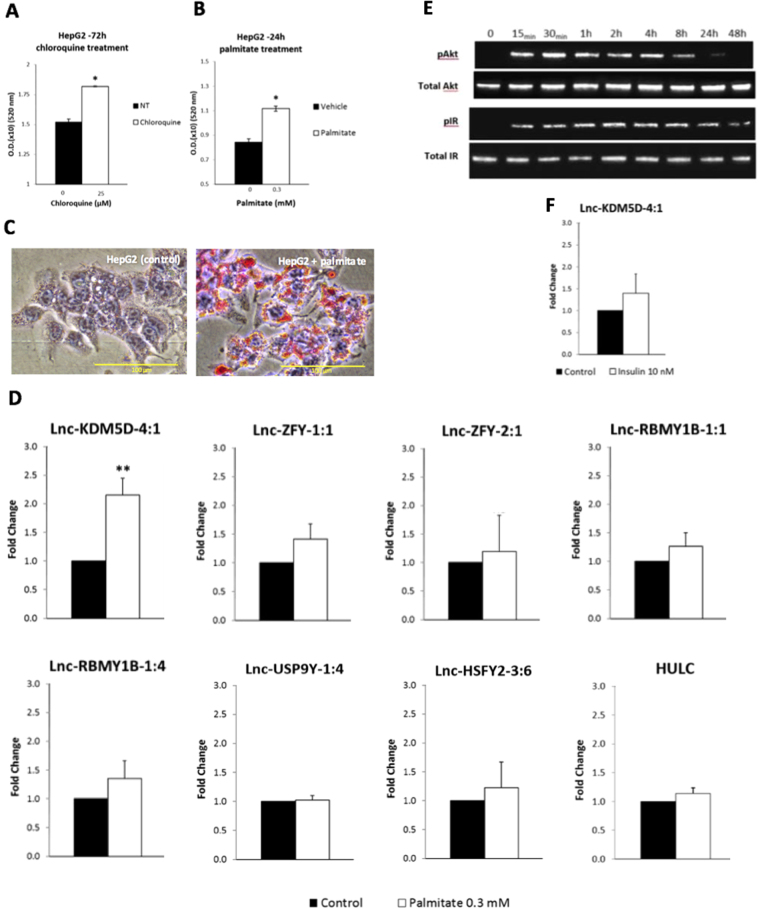

The effects of fatty acid palmitate on the transcript expression of Y chromosome-linked lincRNAs in a steatosis HepG2 cell line

Positive correlations between CAD and high levels of free fatty acids (FFAs) in steatosis hepatocytes have been previously demonstrated in vitro using HepG2 cells11–14. To create a FFA-induced steatosis liver cell line, HepG2 cells were stimulated with 0.3 mmol/L of palmitate for 24 hours to induce lipid accumulation within the cells14. Two methods were used to assess the results: quantification of the lipid accumulation by absorbance measurement (Fig. 2A,B) and examination of the intracellular distribution of lipid droplets by Oil Red O (ORO) staining using microscopy (Fig. 2C). To confirm the ability of our assay to generate the required cell phenotypes, we compared the magnitude of lipid accumulation within the target cells with that generated by the positive control for inducing steatosis, the chloroquine (based on manufacturer’s recommendations). Results with chloroquine showed a similar significant increase in lipid accumulation within the treated cells when compared to the control cells (Fig. 2A). The absorbance measurement of the lipid quantification (Fig. 2B) suggested that HepG2 cells had acquired the palmitate-induced steatosis phenotype. These results were further validated by microscopy demonstrating a clear increase of ORO-stained lipid droplets (red) in the peri-nuclear region of the cells in comparison to the control cells (Fig. 2C). Real-time PCR results showed that 24 h-treatment with palmitate triggered a significant 2.16-fold increase in the expression of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 (p-value = 0.00216) in HepG2 cells. No significant increase in the expression of the transcripts lnc-ZFY-1:1, lnc-ZFY-2:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:4, lnc-USP9Y-1:4, lnc-HSFY2-3:6, and HULC was observed (p-value > 0.05) (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Expression of MSY lincRNAs in palmitate-induced steatosis and in insulin-resistant HepG2 cells. (A,B) Quantification of the lipid accumulation by absorbance measurement after treatment with palmitate at 0.3 mmol/L (0.3 mM) (A), and chloroquine (as positive control) at 25 µmol/L (25 µM) (B). Microscopy results of the intracellular distribution of lipid droplets stained in red by the Oil Red O solution after 24 h of treatment with either the vehicle or with the palmitate (C). The addition of palmitate after 24 h triggers a significant increase (Fold Change = 2.16; p-value = 0.00216) in the expression of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 in HepG2 cells in comparison to cells not treated with palmitate (control cells) (D). No significant increase in the expression of lnc-ZFY-1:1, lnc-ZFY-2.1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:4, lnc-USP9Y-1:4, lnc-HSFY2-3:6, and HULC is observed. (E) Western blot analysis of phosphorylated protein kinase B (pAkt), Total Akt, phosphorylated insulin-receptor (pIR), and Total IR (gel cropped). Antibodies were used to immunodetect the levels of pAkt, Total Akt, pIR and Total IR in an increasingly insulin-resistance HepG2 cell line. For protein phosphorylation detection, 10 nM insulin was added for 30 min before cell lysates harvest at the indicated time. Western blot analysis was performed on two independent experiments (Uncropped gel images Supplementary Figure S1). (F) Real-time PCR results of the 24 h insulin-stimulated HepG2 cells with no significant changes in the expression of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 in comparison to the cells not treated (control cells) (Fold Change = 1.39; p-value > 0.05). Data are relative to the housekeeping gene actin beta (ACTB). Error bars indicate ± SD calculated from sextuplicate wells (A,B). NT, no treatment; (n = 4). Statistical significance: *p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01.

The effects of insulin on the lncRNA transcript lnc-KDM5D-4:1 expression in an insulin-resistant HepG2 cell line

To investigate the possible correlation between steatosis and insulin-resistance, the potential effect of insulin resistance on the expression of lnc-KDM5D-4 was studied. To create an insulin-resistant cell line, HepG2 cells were stimulated with 10 nM of insulin solution over 0, 0.25, 0.5, 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h replacing the media and insulin every 8 h. Total cellular protein was extracted using RIPA buffer and 20 μg of total cellular protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and subsequently blotted onto Immobilon-PVDF membrane. The relative levels of phosphorylated protein kinase B (pAkt) or phosphorylated insulin-receptor (pIR) were detected relative to Total Akt and Total IR respectively (Fig. 2E). Western blot analysis showed that following 30 min of insulin treatment, there was an increase in the levels of pAkt that were further increased at 2 and 4 h of insulin treatment, as similarly for pIR. The level of phosphorylation then rapidly decreased at 8 h and became almost undetectable at 24 and 48 h. The level of phosphorylation of the IR decreased from 24 h. Overall, there was no change in Total Akt and IR proteins observed, suggesting that the cells had obtained the insulin-resultant phenotype (Fig. 2E). To determine if lnc-KDM5D-4 responded to insulin-resistance, its expression was analysed by real-time PCR. Results showed no significant change in the expression of lnc-KDM5D-4 in cells stimulated with insulin for 24 h compared to the control cells (Fig. 2F).

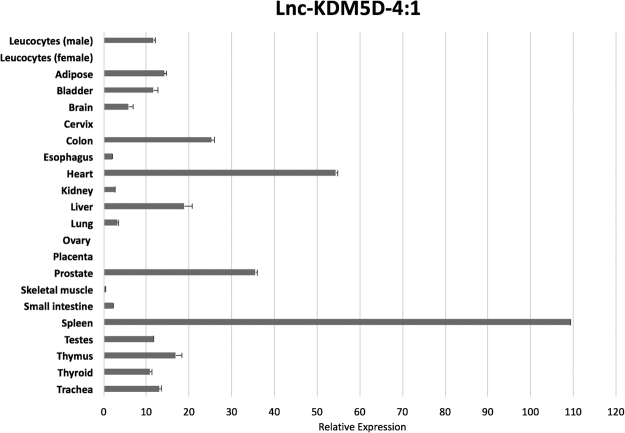

A survey of the expression of the lncRNA transcript lnc-KDM5D-4:1 in 21 different normal human tissues

To gain a better understanding about the biological role of lnc-KDM5D-4, we examined its expression across 21 normal human tissue types including adipose, bladder, brain, cervix, colon, esophagus, heart, kidney, liver, lung, ovary, placenta, prostate, skeletal muscle, small intestine, spleen, testes, thymus, thyroid, trachea, male and female leucocytes from WBCs. The real-time PCR analysis revealed that lnc-KDM5D-4 shows ubiquitous expression with the highest level of expression in the spleen and the heart. As expected, no expression was found in female tissues such as cervix, ovary, and placenta as well as in female leucocytes (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Lnc-KDM5D-4 gene expression analysis in healthy human tissues. The expression of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 in 21 different normal, human tissues – real-time PCR (no expression observed in female tissues such as cervix, ovary, placenta, and female leucocytes), the expression estimates are relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and error bars indicate ± S.E.M. (n = 3).

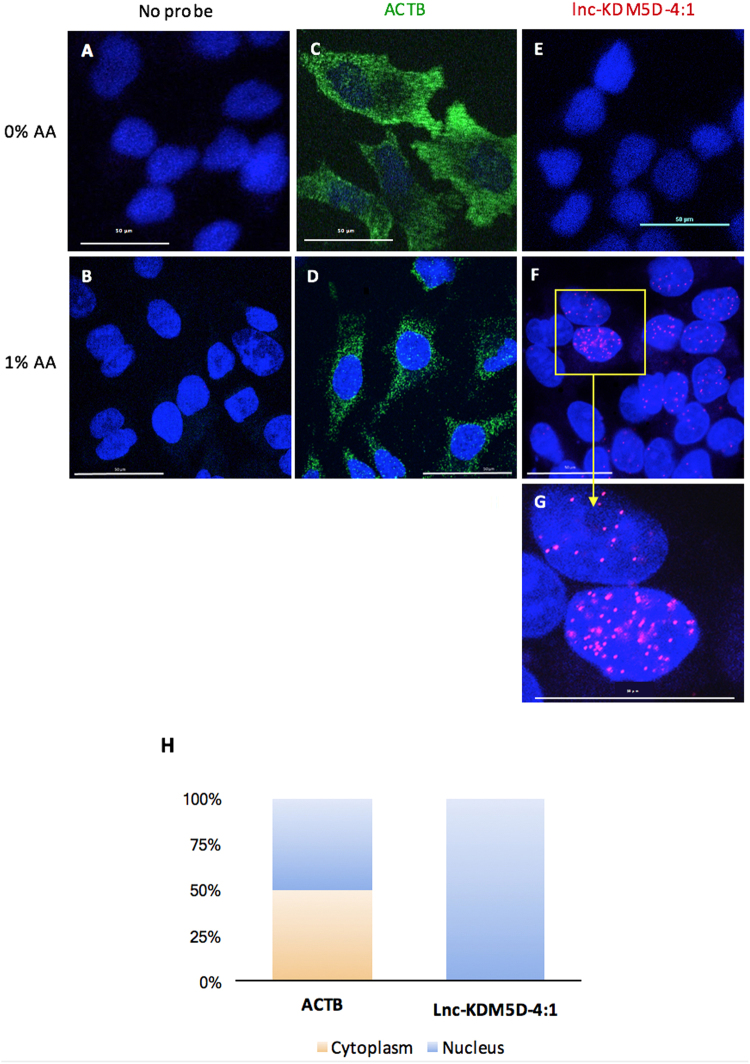

Subcellular localization of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 transcripts in HepG2 cells

To gain fundamental insights into the biology and potential cellular role of lnc-KDM5D-4 in the regulation of cellular functions24, we examined its subcellular localization using RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (RNA FISH) with single-molecule sensitivity. To achieve a controlled system as background image, the assay was performed without addition of glacial acetic acid (AA) to the fixation solution (Fig. 4A,C,E). This way, although significant cytoplasmic signals were observed for the actin beta (ACTB) housekeeping gene probe (green) (Fig. 4C), any signal obtained was the result of the lnc-KDM5D-4:1 probe (red) (Fig. 4E). These results suggested that lnc-KDM5D-4:1 transcripts were localised only in the nucleus. By adding 1% of AA into the fixation solution, the fluorescence of single-RNA molecule of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 (red) displays a strictly nuclear distribution (Fig. 4F,G and Supplementary Video S1). The ACTB RNA FISH results (Fig. 4C,D) confirmed the efficiency of reagents and methods used for this assay. As negative controls, wells with only secondary probes were tested and no signal displays were seen, as expected, (Fig. 4A,B) confirming that signals obtained for ACTB and lnc-KDM5D-4:1 are not due to the mere expression of the secondary probes. RNA FISH results were then confirmed by real-time PCR using nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs, separately isolated from HepG2 cells, as shown in Fig. 4H.

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 in HepG2 cells. (A,B) Cells without probes (negative control). (C,D) actin beta (ACTB fluorescence in situ hybridization (ACTB-FISH) (green) used as housekeeping gene and positive control for the RNA FISH assay. (F,G, and Supplementary Video S1) RNA FISH shows the nuclear localization of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 (red). Each probe was tested with (B,D,F,G, and Supplementary Video S1) or without (A,C,E) addition of 1% of acetic acid (AA) at the cell fixation step. This resulted in no observable nuclear signal for lnc-KDM5D-4:1 when AA is not added to the fixation solution (E). (H) Real-time PCR lnc-KDM5D-4:1 transcript expression results from nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs isolated separately from HepG2 cells before reverse transcription, then real-time PCR. Results show a nuclear expression, exclusively, of lnc-KDM5D-4:1 in comparison to ACTB which is approximately half nuclear and half cytoplasmic. Microscopy confocal images represent three independent experiments (n = 3). Confocal microscope magnification: 60x.

The effects of lnc-KDM5D-4 knockdown on genes in HepG2 cells

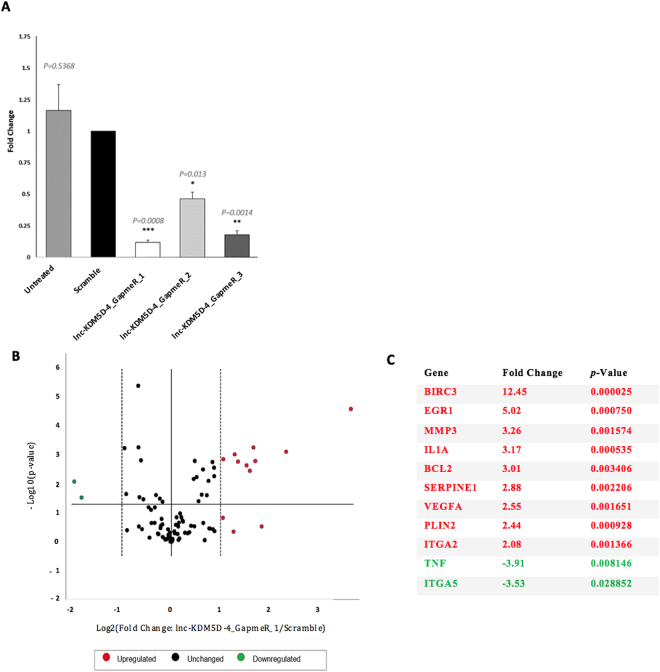

To elucidate the potential biological role of Y-linked lnc-KDM5D-4 in the liver, a knockdown using the advanced Locked Nucleic Acid GapmeRs (antisense oligonucleotides (AOs)) that blocked lnc-KDM5D-4:1 activity was performed. This was followed by a gene expression analysis using the RT2 Profiler PCR Array. Specifically, we transfected HepG2 cells with GapmeRs targeting lnc-KDM5D-4:1 using three different probes separately (lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_1, lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_2 and lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_3) to target three different sites of lnc-KDM5D-4:1. A random scrambled sequence that contains no known homology to the human, mouse, or rat genome was used as a negative control. Cells without transfection (Untreated) were also used to verify the Scramble (negative control probe) for non-specificity. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. AO-mediated silencing of lnc-KDM5D-4 was assessed in real-time PCR. The highest knockdown efficiency was obtained when the cells are treated with 10 nmol/L of the lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_1 with a transcript reduction of 88% (Fold change = 0.12; p-value = 0.0008). The comparison of transfected cells with GapmeRs and Scramble (control GapmeR) to Untreated samples showed that there was no significant effect of transfection reagent or transfection reagent plus GapmeR respectively, on the cell (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Lnc-KDM5D-4 knockdown and associated atherosclerosis-relevant genes. Cells were transfected with Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) GapmeRs targeting lnc-KDM5D-4:1 RNA or random scrambled sequence. (A) Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. AO-mediated silencing of lnc-KDM5D-4 was assessed in real-time PCR (normalised to ACTB as housekeeping control gene). The cells demonstrate antisense oligonucleotide knockdown of nuclear-located lnc-KDM5D-4 with the 3-different tested GapmeRs; a highest knockdown efficiency was achieved with the lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_1 [transcript reduction by 88% (Fold change = 0.12; p-value = 0.0008)]. Comparison of transfected cells with GapmeRs, and Scramble to Untreated samples (negative control) showed that there was no significant effect of transfection reagent or transfection reagent plus GapmeR respectively on the cell. (B,C) A Human Atherosclerosis RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array was utilized to profile the expression of 84 genes involved in atherosclerosis between HepG2 cells transfected with GapmeR targeting lnc-KDM5D-4 (lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_1) and scrambled cells. Relative expression levels of these genes were normalised to a set of housekeeping genes (Supplementary Table S6). Three independent biological samples were used (n = 3). The volcano plot combines a p-value statistical test with the fold change enabling identification of genes with both large and small expression changes that are statistically significant are represented; upregulated genes (red), downregulated genes (green), and unchanged genes (black) (B). In transfected cells compared to untransfected cells, results determine that 9 genes were significantly over-expressed ((p-value < 0.05; Fold Change >2): BIRC3 (baculoviral IAP repeat containing 3), EGR1 (early growth response 1), MMP3 (matrix metallopeptidase 3), IL1A (interleukin 1 alpha), BCL2 (BCL2, apoptosis regulator), SERPINE1 (serpin family E member 1), VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor A), PLIN2 (perilipin 2), and ITGA2 (integrin subunit alpha 2); and 2 genes were significantly under-expressed ((p-value < 0.05; Fold Change <−2.00): ITGA5 (integrin subunit alpha 5), and TNF (tumor necrosis factor) (C). The significant dysregulated genes are summarized in Supplementary Figure S2 with their pathways associated with the most represented ‘anti-apoptosis pathway’. Statistical significance: *p-value < 0.05; **p-value < 0.01; ***p-value < 0.001.

Following that, the Human Atherosclerosis RT2 Profiler PCR Array was used to compare cells transfected with the lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_1 and cells transfected with the control GapmeR (Scramble) (Fig. 5B,C). This array profiled the expression of 84 genes related to atherosclerosis. Our results showed that reduced lnc-KDM5D4:1 transcript level in HepG2 cells was associated with changes in expression of 11 genes: BIRC3 (baculoviral IAP repeat containing 3), EGR1 (early growth response 1), MMP3 (matrix metallopeptidase 3), IL1A (interleukin 1 alpha), BCL2 (BCL2, apoptosis regulator), SERPINE1 (serpin family E member 1), VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor A), PLIN2 (perilipin 2), ITGA2 (integrin subunit alpha 2), ITGA5 (integrin subunit alpha 5), and TNF (tumor necrosis factor) (Fig. 5C). Most of these genes mapped to anti-apoptosis pathway (Supplementary Fig. S2). Finally, the new human tissue-specific network webserver GIANT22 was used to highlight the potential functional interactions of these genes with other protein-coding genes in hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. S3).

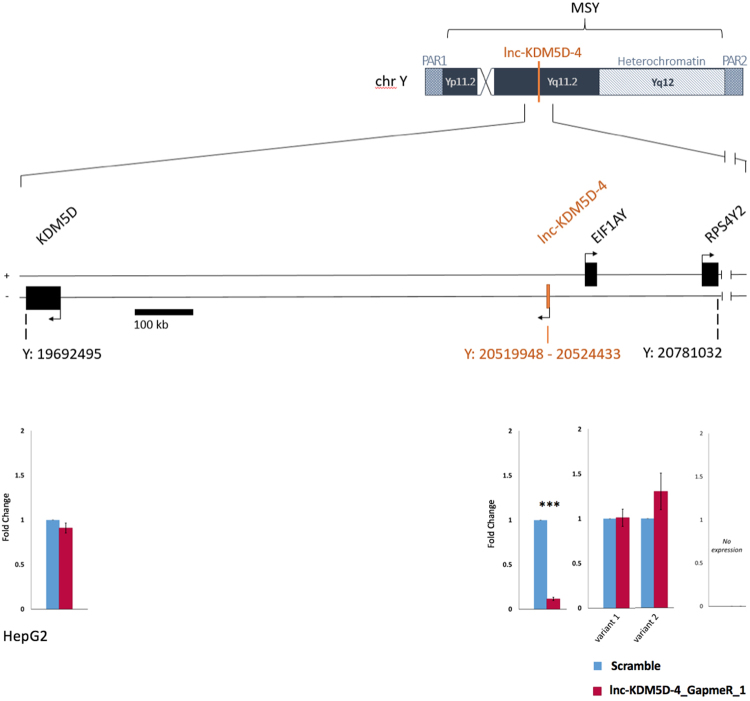

Previous studies on transcriptional regulation models showed that lncRNAs, notably lincRNAs, may operate in cis by regulating their immediate neighbouring protein-coding genes leading to either an increase or reduction of their expression16,25,26. After confirmation of the lnc-KDM5D-4 knockdown in HepG2 cells, we examined the potential transcriptional activity of the nearest neighbouring protein-coding genes by lnc-KDM5D-4 such as KDM5D (lysine demethylase 5D), EIF1AY (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1A, Y-linked), and RPS4Y2 (ribosomal protein S4, Y-linked 2) located within 1.1 MB window centred on lnc-KDMM5D-4. Real-time PCR analysis showed that there were no significant changes (p-value > 0.05) in the expression of these neighbouring Y chromosome protein-coding genes in cells transfected with the lnc-KDM5D-4_GapmeR_1 compared to the control cells (Scramble) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of protein-coding genes surrounding the lncRNA gene lnc-KDM5D-4 on the human Y chromosome. Protein-coding genes within 1.1 MB window centred on lnc-KDM5D-4. Upstream genes: EIF1AY (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1A, Y-linked), which encodes for two transcripts, and RPS4Y2 (ribosomal protein S4, Y-linked 2). Downstream genes: KDM5D (lysine demethylase 5D). The knockdown of lnc-KDM5D-4 in HepG2 cells does not influence the expression of its nearest neighbouring protein-coding genes. MSY: male-specific region of the Y chromosome. PAR1: pseudo-autosomal region 1. PAR2: pseudo-autosomal region 2. Position on the Y chromosome in base pair (bp); Human GRCh38/hg38.

Discussion

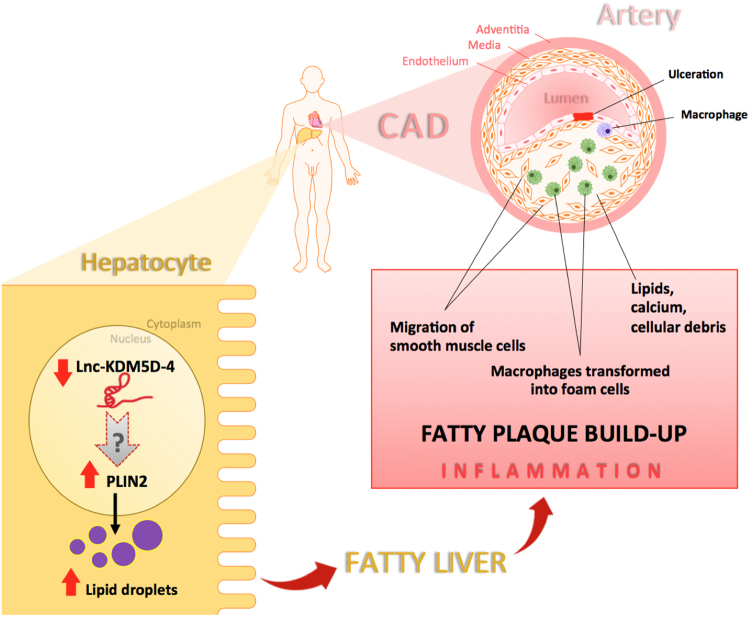

Genetic variation within the Y chromosome has been linked to human lipid levels and cardiovascular disease2–4,6,27,28. Here we provide novel data suggestive of a potential role for one of the Y chromosome lincRNA, lnc-KDM5D-4, in the hepatic metabolism of lipids and atherosclerosis. Our findings demonstrate that lnc-KDM5D-4 is a nuclear-retained lincRNA that has a regulatory effect on the mRNA expression of genes such as Perilipin 2 (PLIN2), that in turn, lead to increased lipid droplets formation in hepatocytes. We propose that this link may, in part, contribute to the association between certain Y chromosome haplogroups and atherosclerosis.

There is currently no information regarding Y chromosome-linked lncRNAs in human traits and disease. This is due to the fact that the Y chromosome is routinely excluded from genome analysis studies into the identification and the functions of lncRNAs in mammals29,30. Indeed, due to the haploid nature of the Y chromosome, the usual methods of analysis (such as genome-wide association studies (GWAS)) cannot be employed to investigate variations. This study provides the first evidence of the expression of Y-linked lincRNA transcripts such as lnc-KDM5D-4:1, lnc-ZFY-1:1, lnc-ZFY-2:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:1, lnc-RBMY1B-1:4, lnc-USP9Y-1:4, and lnc-HSFY2-3:6 in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Further research focusing on these lincRNAs between primary human hepatocytes and HepG2 cells should be done as these lincRNAs may also play a role in HCC, and could be potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of this cancer in men. Our data also provides the first evidence for the up-regulation of the Y-linked lincRNA, known as lnc-KDM5D-4, in response to palmitate treatment in HepG2 cells. However, lnc-KDM5D-4 was not differentially expressed or affected in insulin-resistance HepG2 cells, demonstrating that the results found with the steatosis cell model were independent of those found in the insulin-resistance cells. These results confirmed that the significant changes in expression of lnc-KDM5D-4 after the FFA-palmitate treatment was triggered by the steatosis phenotype, and not by the insulin-resistance phenotype. It was suggested that lnc-KDM5D-4 was then implicated in hepatic steatosis which can occur independently of insulin resistance in the liver. Given the role of FFAs in the pathogenesis of CAD31–33, these results suggest that lnc-KDM5D-4 may play a role in the hepatic metabolism of lipids – a process of well-known relevance to atherosclerosis. Whether aberrant expression of this lincRNA plays an insignificant role in this context, or if it is a mere consequence of disease pathology remains an open question. Further research on lnc-KDM5D-4 should be done to study the role of this Y-linked lincRNA in steatosis-associated atherosclerosis.

Lnc-KDM5D-4:1 transcripts were found to be expressed in adipose, bladder, brain, colon, esophagus, heart, kidney, liver, lung, prostate, skeletal muscle, small intestine, spleen, testes, thymus, thyroid, trachea, and leucocytes suggesting that this lincRNA is widely expressed in male tissues. These findings provide a novel expression profile for lnc-KDM5D-4 across human healthy tissues. Based on these data, we believe that this lincRNA may have other molecular and physiological roles in men.

The main known function of lncRNAs to date is regulation of gene expression34. Lnc-KDM5D-4:1 RNA FISH results suggested that lnc-KDM5D-4:1 is a lincRNA retained within the nucleus of hepatocytes. Concomitantly, these findings were in agreement with the previous observations showing that lncRNA transcripts were enriched in the cell nucleus in HepG2 cells16. This clearly showed that lnc-KDM5D-4 plays a potential role in biological functions taking place within the nucleus24,35 such as the establishment and maintenance of nuclear domains36, shaping of the 3D organization35,37, or acting as enhancer-like RNA by activating its neighbouring genes using a cis-mediated mechanism38,39. Indeed, an exclusively nuclear localization would argue against putative lncRNAs encoding short peptide sequences as translation occurs in the cytoplasm. However, given that its silencing does not affect the expression of its surrounding protein-coding genes, this may argue that it acts in trans rather than in cis.

Among the genes that were affected by lnc-KDM5D-4 knockdown in HepG2 cells, PLIN2 is known to be implicated in lipid metabolism. This protein-coding gene is located on chromosome 9 and belongs to the perilipin gene family that regulate intracellular lipid storage droplets and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion40. Overexpression of PLIN2 has been shown to trigger an increase in lipid droplets formation within hepatocytes via the up-regulation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma isoform (PPAR gamma)41. Furthermore, the up-regulation of PLIN2 was previously associated with liver steatosis42 and atherogenesis43. More recently, PLIN2 expression was also associated with atherosclerosis in patients with carotid stenosis44. On the other hand, the loss of PLIN2 has resulted in reduction of liver steatosis and inflammation45. An overview of the involvement of lnc-KDM5D-4 and its potential interaction with PLIN2 in the context of atherosclerosis and CAD is proposed in Fig. 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram illustrating the potential role of lnc-KDM5D-4 in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is driven by a chronic inflammatory process. Lipid disturbances and other risk factors are thought to cause endothelial injury resulting in monocyte adhesion and migration to the intima, as well as the release of cytokines and growth factors. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles travelling in the blood and carrying cholesterol and triglycerides from the liver to other body tissues get through the endothelium layer due to their size and density, and become oxidized. After migration to the sub-endothelial space, monocytes differentiate into macrophages, which are then able to ingest oxidized-LDL, forming specialized foam cells. Macrophages are not able to process the oxidized-LDL and ultimately grow and rupture depositing a greater amount of oxidized cholesterol into the artery wall. This triggers the recruitment of more monocytes, thus increasing the inflammation and continuing the cycle. This inflammation leads to subendothelial accumulation of fatty substances called atheromatous plaques. In the hepatocytes, the underexpression of the Y chromosome-linked lincRNA lnc-KDM5D-4 results in an overexpression of the gene perilipin 2 (PLIN2) involved in lipid droplet formation within the cells. This increase of expression of PLIN2 may consequently initiates the ‘fatty liver’ or hepatic steatosis promoting atherosclerosis in the coronary arteries of men.

Lnc-KDM5D-4 seems to be not conserved between human and rodents18 which could be due to the unique forces that drive the evolution of the Y chromosome. It is therefore not possible to study further this lncRNA in rodents.

In conclusion, this is the first study on lincRNAs on the human Y chromosome and gene expression analysis. We provide evidence for the potential involvement of one of these lncRNAs, lnc-KDM5D-4, in atherosclerosis and CAD, possibly through the lipid metabolism-associated gene PLIN2 in hepatocytes. Overall, our data adds to the evidence that the human Y chromosome plays an important role in cardiovascular disease in a male specific manner and provides novel insight into potential new therapeutic targets for CAD.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Brendan Yee and Rita Rozmarynowycz (Affymetrix®) for their advice with RNA FISH and for providing reagents. We also thank Fahima Ahmady for her help as Laboratory Technical Officer. This work was supported by funding from an International Postgraduate Research Scholarship at Federation University Australia, the Collaborative Research Network (CRN), and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Project Grant GNT1009490).

Author Contributions

E.M., G.S.C., S.A.M. and F.J.C. planned the experiments; E.M. carried out the experiments; E.M.C. assisted in the RNA FISH; J.M.E. performed the GIANT analysis; E.M. and F.J.C. wrote the manuscript. M.T., G.S.C., E.M.C. and J.M.E., revised the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-17165-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Graves JA, Koina E, Sankovic N. How the gene content of human sex chromosomes evolved. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charchar FJ, et al. Inheritance of coronary artery disease in men: an analysis of the role of the Y chromosome. Lancet. 2012;379:915–922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61453-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charchar FJ, et al. The Y chromosome effect on blood pressure in two European populations. Hypertension. 2002;39:353–356. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charchar FJ, et al. Association of the human Y chromosome with cholesterol levels in the general population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:308–312. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000113291.39267.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina E, Clarence EM, Ahmady F, Chew GS, Charchar FJ. Coronary Artery Disease: Why We should Consider the Y Chromosome. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25:791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.12.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloomer LD, et al. Male-specific region of the Y chromosome and cardiovascular risk: phylogenetic analysis and gene expression studies. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:1722–1727. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skaletsky, H. et al. The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature423, 825-837, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v423/n6942/suppinfo/nature01722_S1.html (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Klattenhoff CA, et al. Braveheart, a long noncoding RNA required for cardiovascular lineage commitment. Cell. 2013;152:570–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schonrock N, Harvey RP, Mattick JS. Long noncoding RNAs in cardiac development and pathophysiology. Circ Res. 2012;111:1349–1362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhury D, Choi YE, Brault ME. Charity begins at home: non-coding RNA functions in DNA repair. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nrm3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita SY, Sakurai A, Nakano M, Kitagawa S, Handa T. Presence of apolipoprotein C-III attenuates apolipoprotein E-mediated cellular uptake of cholesterol-containing lipid particles by HepG2 cells. Lipids. 2011;46:323–332. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3498-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakayama N, et al. Modulators of induction of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 in HepG2 cells by transforming growth factor-beta. Coron Artery Dis. 2011;22:468–478. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32834a3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norikura T, et al. Lignophenols decrease oleate-induced apolipoprotein-B secretion in HepG2 cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;107:813–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2010.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricchi M, et al. Differential effect of oleic and palmitic acid on lipid accumulation and apoptosis in cultured hepatocytes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:830–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabili MN, et al. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1915–1927. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derrien T, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22:1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thornton B, Basu C. Real-time PCR (qPCR) primer design using free online software. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2011;39:145–154. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volders PJ, et al. LNCipedia: a database for annotated human lncRNA transcript sequences and structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D246–251. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui W, Chen SL, Hu KQ. Quantification and mechanisms of oleic acid-induced steatosis in HepG2 cells. Am J Transl Res. 2010;2:95–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battich N, Stoeger T, Pelkmans L. Image-based transcriptomics in thousands of single human cells at single-molecule resolution. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene CS, et al. Understanding multicellular function and disease with human tissue-specific networks. Nat Genet. 2015;47:569–576. doi: 10.1038/ng.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panzitt K, et al. Characterization of HULC, a novel gene with striking up-regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma, as noncoding RNA. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:330–342. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maamar H, Cabili MN, Rinn J, Raj A. linc-HOXA1 is a noncoding RNA that represses Hoxa1 transcription in cis. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1260–1271. doi: 10.1101/gad.217018.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimitrova N, et al. LincRNA-p21 activates p21 in cis to promote Polycomb target gene expression and to enforce the G1/S checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2014;54:777–790. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang KC, et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bloomer LD, et al. Coronary artery disease predisposing haplogroup I of the Y chromosome, aggression and sex steroids–genetic association analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charchar FJ, Tomaszewski M, Strahorn P, Champagne B, Dominiczak AF. Y is there a risk to being male? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:163–168. doi: 10.1016/S1043-2760(03)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guttman M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guttman M, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salonen JT, et al. Serum fatty acids, apolipoproteins, selenium and vitamin antioxidants and the risk of death from coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:226–231. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90839-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarantino G, Caputi A. JNKs, insulin resistance and inflammation: A possible link between NAFLD and coronary artery disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3785–3794. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i33.3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gruzdeva O, et al. Multivessel coronary artery disease, free fatty acids, oxidized LDL and its antibody in myocardial infarction. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:111. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-13-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geisler S, Coller J. RNA in unexpected places: long non-coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:699–712. doi: 10.1038/nrm3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quinodoz S, Guttman M. Long noncoding RNAs: an emerging link between gene regulation and nuclear organization. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clemson CM, et al. An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Mol Cell. 2009;33:717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engreitz JM, et al. The Xist lncRNA exploits three-dimensional genome architecture to spread across the X chromosome. Science. 2013;341:1237973. doi: 10.1126/science.1237973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai F, et al. Activating RNAs associate with Mediator to enhance chromatin architecture and transcription. Nature. 2013;494:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature11884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li W, et al. Functional roles of enhancer RNAs for oestrogen-dependent transcriptional activation. Nature. 2013;498:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nature12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magnusson B, et al. Adipocyte differentiation-related protein promotes fatty acid storage in cytosolic triglycerides and inhibits secretion of very low-density lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1566–1571. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000223345.11820.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogue A, et al. Comparative gene expression profiles induced by PPARgamma and PPARalpha/gamma agonists in human hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okumura T. Role of lipid droplet proteins in liver steatosis. J Physiol Biochem. 2011;67:629–636. doi: 10.1007/s13105-011-0110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chawla A, et al. A PPAR gamma-LXR-ABCA1 pathway in macrophages is involved in cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:161–171. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perisic L, et al. Gene expression signatures, pathways and networks in carotid atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2016;279:293–308. doi: 10.1111/joim.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Najt CP, et al. Liver-specific loss of Perilipin 2 alleviates diet-induced hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310:G726–738. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00436.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.