Abstract

Objectives

Among the challenges in conducting clinical trials in large-vessel vasculitis (LVV), including both giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK), is the lack of standardized and meaningful outcome measures. The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Vasculitis Working Group initiated an international effort to develop and validate data-driven outcome tools for clinical investigation in LVV.

Methods

An international Delphi exercise was completed to gather opinions from clinical experts on LVV-related domains considered important to measure in trials. Patient interviews and focus groups were completed to identify outcomes of importance to patients. The results of these activities were presented and discussed in a “Virtual Special Interest Group” using telephone- and internet-based conferences, discussions via electronic mail, and an in-person session at the 2016 OMERACT meeting. A preliminary core set of domains common for all forms of LVV with disease-specific elements was proposed.

Results

The majority of experts agree with using common outcome measures for GCA and TAK, with the option of supplementation with disease-specific items. Following interviews and focus groups, pain, fatigue and emotional impact emerged as health-related quality of life domains important to patients. Current disease assessment tools, including the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score, were found to be inadequate to assess disease activity in GCA and standardized assessment of imaging tests were felt crucial to study LVV, especially TAK.

Conclusion

Initial data from a clinicians Delphi exercise and structured patients interviews have provided themes towards an OMERACT-endorsed core set of domains and outcome measures.

Keywords: giant cell arteritis, Takayasu’s arteritis, vasculitis, outcome assessment

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK) are large vessel vasculitides (LVV) that share similar features (1). Clinical research in LVV has been hindered by the lack of standardized outcome measures (2). The Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) Vasculitis Working Group leads efforts to advance development of outcome measures in vasculitis, including LVV. During the 2016 OMERACT meeting, a “virtual Special Interest Group” was conducted to discuss the current research findings and propose a preliminary core set of domains. The main discussion points were: a) results of the international LVV Delphi; b) findings of the qualitative studies in TAK; and c) current work on LVV disease activity and damage measures. Following the discussion, a preliminary core set of domains common to LVV with disease-specific elements was proposed.

Methods/Results

Delphi exercise

Given the lack of international consensus on outcome measures to assess LVV, the LVV Task Force conducted an international Delphi exercise to obtain experts’ opinions regarding important disease domains for the assessment of disease outcomes in LVV. Ninety-nine experts were involved. Key findings emerging from this exercise include: i) many domains were common to TAK and GCA but some were distinctly identified with one or the other disease; ii) patient global assessment (PtGA) was accepted as a tool to assess patient-reported outcomes (PRO) in LVV; iii) the majority of experts (at least 70%) agreed to have a common outcome measure tool for both GCA and TAK but that such a measure also be supplemented by disease-specific items for trials of GCA and TAK.

Patient interviews/qualitative research

Generic PRO instruments such as the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36) and PtGA have been previously examined in patients with LVV (3–6). However, these instruments often lack the ability to capture essential disease-specific domains that are of high importance to patients with LVV. The LVV Task Force has completed individual interviews and focus groups with patients in the United States and Turkey to identify key health-related domains that patients consider important in TAK. Thirty-one patients participated (12 patients in the US and 19 patients in Turkey). Purposive sampling was used to include patients with various disease duration and severity. Freelisting and pilesorting methods as well as extensive qualitative review of the transcripts were analyzed using Nvivo (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012). The most salient terms and common themes that emerged were pain and discomfort, fatigue and low energy levels, and emotional impact. Similar qualitative research is now being planned for patients with GCA to identify similarities and differences between the two diseases.

The OMERACT SIG group felt the results of these data about patient preferences should be combined with the results of the Delphi about physician opinions to form the basis of the draft core set of domains.

Assessment of disease activity

There currently exists no clear definition of disease activity in LVV. A systematic review of disease activity and outcome measures was previously published by the OMERACT LVV task force (7). Several disease activity assessment tools have been used in clinical trials of LVV. These tools often use a combination of clinical symptoms, cumulative glucocorticoid dose/duration and acute phase reactants. In terms of a single tool, criteria used by an NIH group for active disease (8), the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS)(9), the Disease Extent Index for Takayasu’s arteritis (DEI.Tak) (10), and the Indian Takayasu’s Arteritis Score 2010 (ITAS2010) (11) have been used in clinical research for TAK (12–14). A similar disease-specific tool does not exist for GCA and a recent study lead by investigators within the OMERACT Vasculitis Working Group found BVAS to have limited utility in GCA (15). A combination of clinical symptoms, glucocorticoids dose or duration, and/or BVAS has been used in clinical trials of GCA (13, 16–18).

Imaging has emerged as a promising diagnostic and critical tool to follow the disease course in LVV. Imaging modalities for LVV include color duplex ultrasonography (19–21), computed tomography angiography (22, 23), magnetic resonance angiography (24–26), and 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography either alone or with computed tomography (27–29). These modalities differ in terms of test characteristics, cost, exposure to radiation, and availability. There is a need for formal validation of imaging modalities for correlation with activity, damage, and outcome in LVV. There also remain major uncertainties about the meaning of radiographic changes in arterial walls (thickening, enhancement, high signal) regarding disease activity and prognosis.

Although acute phase reactants, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, could be of use to assess disease activity (30, 31) in GCA, and are of unclear utility in TAK (32), the exact role of these biomarkers in disease assessment in LVV remains uncertain.

Assessment of disease damage

Besides the Takayasu’s Arteritis Damage Score, there have been no other disease-specific damage indices validated for LVV (33). While the Vasculitis Damage Index (VDI) has been used to assess damage in LVV (34, 35) this tool is non-specific (i.e. it does not capture specific sites of involvement or laterality), includes all-cause damage, including damage unrelated to vasculitis or its treatment, and contains items that are irrelevant to LVV, such as items related to the ear nose and throat, pulmonary and renal systems. The OMERACT LVV Task Force recently completed validation studies of VDI and a new LVV damage tool called the Large Vessel Vasculitis Index of Damage (LVVID) in GCA and TAK. Preliminary results showed that the majority of patients with GCA and TAK have a significant damage burden early in the disease course, however unlike GCA where damage is predominantly due to treatment, damage in TAK is primarily related to the disease.

Discussion

Data and insights expected from trials conducted recently/ongoing

Despite the lack of standardized outcome measures, several randomized clinical trials of LVV have been conducted recently with various success. In particular, four major clinical trials examining the role of various biologic medicines are of interest: A randomized trial of abatacept for the treatment of LVV (36, 37), a phase 2 randomized trial of tocilizumab in GCA (18) and TAK (38), a phase III randomized trial of tocilizumab in GCA (GiACTA) (39), and a phase III randomized trial of sirukumab in GCA (SIRRESTA; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02531633). Other investigational drugs are being explored for the treatment of LVV such as uztekinumab (NCT02955147), baricitinib (NCT03026504), and anakinra (NCT02902731). Outcome definitions for these clinical trials are similar and use a combination of relapse-free survival, cumulative glucocorticoid dose/duration, physician global assessment, acute phase reactants, and patient-reported outcomes. Using patients’ symptoms and acute phase reactants as indicators of disease activity may prove suboptimal given the potential for ongoing inflammation in asymptomatic patients (8) and the lack of appropriate specificity and sensitivity of acute phase reactants (30, 40). Additionally, using a dichotomous outcome measure such as active disease versus remission may miss a scale of response that is not necessarily captured in relapse-free survival assessment. Finally, if the recently-studied biologic therapies prove to be highly effective as glucocorticoid-sparing agents in LVV, reassessment may be needed when using cumulative glucocorticoid dose/duration as an outcome measure.

The OMERACT SIG group recognizes that new measures of disease activity in LVV need to be developed that incorporate several approaches, especially including PROs and imaging. It is anticipated that analysis of data from recently-completed and ongoing clinical trials in GCA and TAK will help advance disease assessment in LVV.

Proposal of a preliminary core set of domains in LVV

As previously mentioned, the majority of experts in LVV voted through the Delphi exercise to have common outcome domains and measures for GCA and TAK supplemented with disease-specific elements. The benefits to having common measures include ease of implementation, and potential applicability to other LVVs such as idiopathic aortitis.

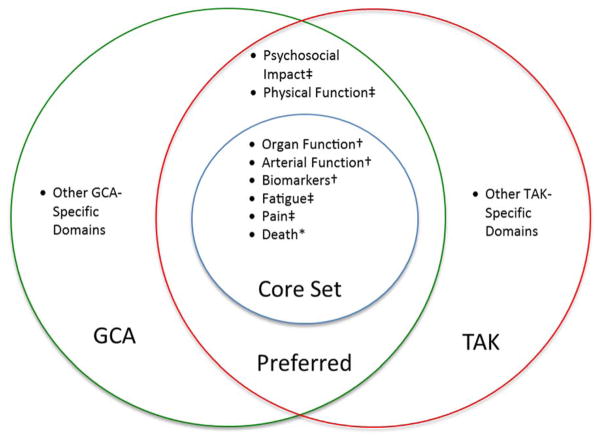

During the OMERACT LVV SIG the group proposed a preliminary set of core domains for use in clinical trials of LVV (Figure 1) that includes a core set of domains with additional disease-specific elements. This approach to domain selection is congruent with the OMERACT Filter 2.0 methodology, including the 2 major concepts of impact of health conditions and pathophysiologic manifestations, and the 3 mandatory core areas of death, life impact, and pathophysiological manifestations.

Figure 1.

A draft core set (domains requiring some representation by a outcome measures in all trials) and additional preferred domains i) common to both giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK), and ii) separate disease-specific domains. The suggested core domains fall under the mandatory core areas of OMERACT filter 2.0: *Death, ‡life impact, and †pathophysiologic manifestations.

Summary and future research agenda

Steady progress has been made to develop a set of outcome measures useful in clinical trials of LVV. The Delphi exercise identified domains of interest and outcome measures for the assessment of LVV and highlighted the importance of having a common set of domains and outcome measures for GCA and TAK, supplemented with disease-specific elements. The qualitative research identified domains of importance to patients from their own perspectives. Validation studies of the current disease activity and damage tools including BVAS and VDI underlined the shortcomings of these assessment tools in LVV. Table 1 shows the OMERACT checklist items that have been completed so far to draft an initial core set of domains and the future steps that have been planned. It is the ultimate goal OMERACT Vasculitis Working Group LVV Task Force to develop an OMERACT-endorsed, internationally-recognized core set of outcome measures for LVV for use in clinical trials.

Table 1.

OMERACT Master Checklist for Developing Core Outcome Measurement Set for Large-Vessel Vasculitis and Future Steps Planned by the OMERACT Vasculitis Working Group Large-Vessel Vasculitis Task Force

| # | Item* | OMERACT Checklist Item | Completed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly of working group and work plan | |||

| 1 | 3.B.1 | Forming an OMERACT Working Group | x |

| 2 | 3.B.2 | Stakeholder groups and their contacts identified | x |

| 3 | 3.B.3 | Thorough review of domain and instruments previously used | x |

| 4 | 3.B.4 | Implementation of Delphi and or Focus Groups | x |

| Core Domain Set selection | |||

| 5 | 3.C.1.1 | Definition of Context: setting (scope) | x |

| 6 | 3.C.2.1 | Deciding on the inclusion of Resource Use | x |

| 7 | 3.C.3.1 | Literature review of domains (and instruments), part 1: what has been measured? | x |

| 8 | 3.C.4.1 | Identification or definition of other domains of interest | x |

| 9 | 3.C.5.1 | Formulation of draft Core Domains-at least 1 per Core Area | x |

| 10 | 3.C.6.1 | Formulation of core contextual factors | Pending |

| 11 | 3.C.7.1 | Formulation of core adverse events, if any | Pending |

| Working group vote | Working group agrees they have Draft Core Domain Set prepared | Pending | |

| 12 | 3.C.8.1 | OMERACT consensus on Core Domain Set and timeline for update cycle | Pending |

| Future steps planned by the OMERACT Vasculitis Working Group Large-Vessel Vasculitis Task Force | |||

| 1 | Report findings from a Delphi exercise, qualitative studies in TAK, and analyses of damage assessment tools in LVV. | ||

| 2 | Conduct qualitative interviews with patients with GCA to identify key themes and domains of high importance to patients with GCA. | ||

| 3 | Further determine the differences and commonalities between GCA and TAK regarding disease experience that can assist in identifying disease-specific domains of interest. | ||

| 4 | Assess the need to develop a disease-specific PRO for GCA and/or TAK. | ||

| 5 | Incorporate data on the utility of imaging modalities in GCA and TAK into the outcome development program for LVV. | ||

| 6 | Finalize a draft core set of domains and identify the best candidate tools to measure these domains. | ||

| 7 | Test the draft core set of outcomes in cohorts and trials. | ||

Item number in the OMERACT 2.0 Handbook.

OMERACT: Outcome Measures in Rheumatology; GCA: Giant Cell Arteritis; LVV: Large-Vessel Vasculitis; TAK: Takayasu’s Arteritis.

What is novel about this work?

Outlines the work to date and ongoing research to develop new outcome measures for large-vessel vasculitis

Describes the inclusion of the patient perspective in defining core domains of importance in the study of large-vessel vasculitis

Presents a draft core domain set for large-vessel vasculitis

Summarizes a new research agenda to develop data- and consensus-driven outcomes for large-vessel vasculitis

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

This work was supported in part by the Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium (VCRC) (U54 AR057319 and U01 AR5187404), part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS). The VCRC is funded through collaboration between NCATS, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and has received funding from the National Center for Research Resources (U54 RR019497).

Contributor Information

Antoine G. Sreih, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Fatma Alibaz-Oner, Associate Professor of Rheumatology, Fatih Sultan Mehmet Training and Research Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey.

Tanaz A. Kermani, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Sibel Z. Aydin, Associate Professor in Rheumatology, Division of Rheumatology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Peter F. Cronholm, Associate Professor of Family Medicine, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Trocon Davis, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Ebony Easley, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Ahmet Gul, Professor of Rheumatology, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Istanbul University Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Alfred Mahr, Professor of Internal Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University Paris Diderot, Paris, France.

Carol A. McAlear, Division of Rheumatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Nataliya Milman, Assistant Professor, Division of Rheumatology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON; Division of Rheumatology, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON; Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Joanna C Robson, Consultant Senior Lecturer, University of the West of England; Honorary Senior Lecturer, University of Bristol; Honorary Consultant in Rheumatology, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol, UK.

Gunnar Tomasson, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Haner Direskeneli, Professor of Rheumatology, Division of Rheumatology, Marmara University, School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey.

Peter A. Merkel, Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology Division of Rheumatology and Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

References

- 1.Furuta S, Cousins C, Chaudhry A, Jayne D. Clinical features and radiological findings in large vessel vasculitis: are Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis 2 different diseases or a single entity? J Rheumatol. 2015;42:300–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.140562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydin SZ, Direskeneli H, Sreih A, Alibaz-Oner F, Gul A, Kamali S, et al. Update on Outcome Measure Development for Large Vessel Vasculitis: Report from OMERACT 12. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:2465–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yilmaz N, Can M, Oner FA, Kalfa M, Emmungil H, Karadag O, et al. Impaired quality of life, disability and mental health in Takayasu’s arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1898–904. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akar S, Can G, Binicier O, Aksu K, Akinci B, Solmaz D, et al. Quality of life in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis is impaired and comparable with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:859–65. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abularrage CJ, Slidell MB, Sidawy AN, Kreishman P, Amdur RL, Arora S. Quality of life of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.044. discussion 36–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kupersmith MJ, Speira R, Langer R, Richmond M, Peterson M, Speira H, et al. Visual function and quality of life among patients with giant cell (temporal) arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2001;21:266–73. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Direskeneli H, Aydin SZ, Kermani TA, Matteson EL, Boers M, Herlyn K, et al. Development of outcome measures for large-vessel vasculitis for use in clinical trials: opportunities, challenges, and research agenda. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1471–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J, Leavitt RY, Fauci AS, Rottem M, et al. Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:919–29. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-11-199406010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luqmani RA, Bacon PA, Moots RJ, Janssen BA, Pall A, Emery P, et al. Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) in systemic necrotizing vasculitis. QJM. 1994;87:671–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aydin SZ, Yilmaz N, Akar S, Aksu K, Kamali S, Yucel E, et al. Assessment of disease activity and progression in Takayasu’s arteritis with Disease Extent Index-Takayasu. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1889–93. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misra R, Danda D, Rajappa SM, Ghosh A, Gupta R, Mahendranath KM, et al. Development and initial validation of the Indian Takayasu Clinical Activity Score (ITAS2010) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1795–801. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, Brasington RD, Lenschow DJ, Liang P. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with difficult to treat Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2296–304. doi: 10.1002/art.20300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henes JC, Mueller M, Pfannenberg C, Kanz L, Koetter I. Cyclophosphamide for large vessel vasculitis: assessment of response by PET/CT. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:S43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goel R, Danda D, Mathew J, Edwin N. Mycophenolate mofetil in Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:329–32. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kermani TA, Cuthbertson D, Carette S, Hoffman GS, Khalidi NA, Koening CL, et al. The Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score as a Measure of Disease Activity in Patients with Giant Cell Arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:1078–84. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.151063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Silva M, Hazleman BL. Azathioprine in giant cell arteritis/polymyalgia rheumatica: a double-blind study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1986;45:136–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.45.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seror R, Baron G, Hachulla E, Debandt M, Larroche C, Puechal X, et al. Adalimumab for steroid sparing in patients with giant-cell arteritis: results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:2074–81. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villiger PM, Adler S, Kuchen S, Wermelinger F, Dan D, Fiege V, et al. Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1921–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00560-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinha D, Mondal S, Nag A, Ghosh A. Development of a colour Doppler ultrasound scoring system in patients of Takayasu’s arteritis and its correlation with clinical activity score (ITAS 2010) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:2196–202. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt WA, Blockmans D. Use of ultrasonography and positron emission tomography in the diagnosis and assessment of large-vessel vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:9–15. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000147282.02411.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karassa FB, Matsagas MI, Schmidt WA, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analysis: test performance of ultrasonography for giant-cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:359–69. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prieto-Gonzalez S, Arguis P, Garcia-Martinez A, Espigol-Frigole G, Tavera-Bahillo I, Butjosa M, et al. Large vessel involvement in biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis: prospective study in 40 newly diagnosed patients using CT angiography. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1170–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prieto-Gonzalez S, Garcia-Martinez A, Tavera-Bahillo I, Hernandez-Rodriguez J, Gutierrez-Chacoff J, Alba MA, et al. Effect of glucocorticoid treatment on computed tomography angiography detected large-vessel inflammation in giant-cell arteritis. A prospective, longitudinal study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e486. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tso E, Flamm SD, White RD, Schvartzman PR, Mascha E, Hoffman GS. Takayasu arteritis: utility and limitations of magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1634–42. doi: 10.1002/art.10251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papa M, De Cobelli F, Baldissera E, Dagna L, Schiani E, Sabbadini M, et al. Takayasu arteritis: intravascular contrast medium for MR angiography in the evaluation of disease activity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:W279–84. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenigkam-Santos M, Sharma P, Kalb B, Oshinski JN, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography in extracranial giant cell arteritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:306–10. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31822acec6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuchs M, Briel M, Daikeler T, Walker UA, Rasch H, Berg S, et al. The impact of 18F-FDG PET on the management of patients with suspected large vessel vasculitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:344–53. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1967-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soussan M, Nicolas P, Schramm C, Katsahian S, Pop G, Fain O, et al. Management of large-vessel vasculitis with FDG-PET: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e622. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umekita K, Takajo I, Miyauchi S, Tsurumura K, Ueno S, Kusumoto N, et al. [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is a useful tool to diagnose the early stage of Takayasu’s arteritis and to evaluate the activity of the disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2006;16:243–7. doi: 10.1007/s10165-006-0485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kermani TA, Schmidt J, Crowson CS, Ytterberg SR, Hunder GG, Matteson EL, et al. Utility of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:866–71. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyle V, Cawston TE, Hazleman BL. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein in the assessment of polymyalgia rheumatica/giant cell arteritis on presentation and during follow up. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:667–71. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.8.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason JC. Takayasu arteritis--advances in diagnosis and management. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:406–15. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajappa SM. Outcome of Vascular Interventions in Takayasu Arteritis Using the Takayasu Arteritis Damage Score. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2011;63:S588–S88. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omma A, Erer B, Karadag O, Yilmaz N, Oner FA, Yildiz F, et al. Cross-Sectional Assessment of Damage in Takayasu Arteritis with a Validated Tool. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2012;71:224–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Omma A, Erer B, Karadag O, Yilmaz N, Alibaz-Oner F, Yildiz F, et al. Remarkable Damage along with poor quality of life in Takayasu arteritis: cross-sectional results of a long-term followed-up multi-center cohort. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016 In press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langford CA, Cuthbertson D, Ytterberg SR, Khalidi N, Monach PA, Carette S, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Abatacept (CTLA-4Ig) for the Treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:837–45. doi: 10.1002/art.40044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langford CA, Cuthbertson D, Ytterberg SR, Khalidi N, Monach PA, Carette S, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Abatacept (CTLA-4Ig) for the Treatment of Takayasu Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:846–53. doi: 10.1002/art.40037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakaoka YIM, Takei S, Tanaka Y, Ishii T, Yokota S, Nomura A, Yoshida S, Nishimoto N. Efficacy and Safety of Tocilizumab in Patients with Refractory Takayasu Arteritis: Results from a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial in Japan. 2016 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Unizony SH, Dasgupta B, Fisheleva E, Rowell L, Schett G, Spiera R, et al. Design of the tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis trial. Int J Rheumatol. 2013;2013:912562. doi: 10.1155/2013/912562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salvarani C, Cantini F, Boiardi L, Hunder GG. Laboratory investigations useful in giant cell arteritis and Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:S23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]