Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) is a multifunctional cytokine which is importantly implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis. The current study provides novel evidence that TGFβ upregulates the expression of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), including IGF1R, EGFR, PDGFβR, and FGFR1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells. This, in turn, sensitized HCC cells to individual cognate RTK ligands, leading to cell survival. Our data showed that the TGFβ-mediated increase in growth factor sensitivity led to evasion of apoptosis induced by the mutikinase inhibitor, sorafenib. Conversely, we observed that inhibition of the TGFβ signaling pathway by LY2157299, a TGFβRI kinase inhibitor, enhanced sorafenib-induced apoptosis, in vitro. Our findings disclose an important interplay between TGFβ and RTK signaling pathways, which is critical for hepatocellular cancer cell survival and resistance to therapy.

Keywords: TGFβ, sorafenib, RTKs, IGF1R, Akt, HCC

INTRODUCTION

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) is a secreted protein that regulates a wide variety of cellular processes including apoptosis and proliferation. The TGFβ signal is propagated through its type I and II receptors to activate intracellular messengers, SMAD2 and SMAD3. Upon phosphorylation, SMAD2 and SMAD3 form heterotrimeric complexes with SMAD4, translocate to the nucleus and coordinate expression of target genes [1]. Noncanonical TGFβ signaling includes activation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) [2] and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways [3]. The response to TGFβ signaling can differ dramatically depending on cell type [4]. For example, TGFβ triggers proliferation of quiescent fibroblasts [5], while functioning as a tumor suppressor, inhibiting division [6], and inducing apoptosis in hepatocytes [7]. Following the transformation of hepatocytes to hepatic tumor cells, however, TGFβ can lose its growth inhibitory and proapoptotic effects, and instead cause cells to undergo the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) [8], and increase cell capacity for colony formation [9], both processes intricately involved in metastasis. Coulouarn et al. [10] have shown that hepatocytes exhibit “early” and “late” gene expression patterns depending on length of exposure to TGFβ, and that HCC patients with “late” signatures have poorer prognosis [10]. Other studies show that TGFβ can worsen prognosis by preventing tumor cell death induced by cytotoxic chemotherapies [11,12].

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer type worldwide [13] and has a 5 yr survival rate of merely 12% [14]. The only available systemic therapy for advanced HCC is sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor of RAF, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), and platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) [15]. While sorafenib has been shown to improve survival, patients only gain an average of 3 months of survival before the tumor develops resistance to the drug and patients relapse [16]. This resistance is associated with an increase in PI3K-AKT activity [17], a pathway known to promote cell survival [18,19]. The PI3K-AKT pathway is activated by a variety of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) following receptor-cognate ligand binding. Thus, RTKs have been implicated in the progression of many tumor types, including HCC. For this reason, many ongoing HCC clinical trials are investigating the efficacy of targeting RTKs, including platelet-derived growth factor β receptor (PDGFβR), epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR), insulin like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1R), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR), and hepatocyte growth factor receptor (c-MET) [20]. In the current study, we implicate multiple RTKs as effectors of a TGFβ-mediated circumvention of sorafenib-induced apoptosis.

METHODS

Cell Culture

Human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines, PLC/PRF/5, Hep3B, and Huh7 were not authenticated or tested for contamination but were purchased from ATCC, Manassas, VA, and JCRB Cell Bank, Japan, and experiments were performed at early passage numbers. Cells were cultured at 37°C at 5% CO2, in high glucose DMEM (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MS) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Wildtype cells were serum starved beginning 24h prior to treatment and cells remained in serum free media throughout the duration of each treatment. Stable shIGF1R and shScrambled expressing cells were made by transfection with either pGFP-V-RS-shScrambled or pGFP-VRS-shIGF1R plasmids, using Lipofectamine and PLUS Reagent (Life Technologies). Cells were then treated with 0.5 µg/mL puromycin (Life Technologies) for 3wk, at which point the surviving cells were considered to be stable knockdowns and puromycin was removed. Stable pGFP-V-RS-shScrambled and pGFP-V-RS-shIGF1R cells were then treated in the presence of 10% FBS. Recombinant human IGF1, IGF2, PDGFβ, FGF1, and EGF were purchased from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN. Recombinant human TGFβ1 was purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA. Sorafenib and LY2157299 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, and were dissolved in DMSO (Sigma–Aldrich).

Cell Viability Assays

Cell viability was determined by crystal violet staining. PLC/PRF/5 cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in 6 well dishes. Cells were then serum starved for 24 h, then treated for 48 h with 5 ng/mL TGFβ in serum-free media, followed by 5 µM sorafenib in serum free media for 24 h. Cells were then stained with crystal violet solution.

ChIP

PLC/PRF/5 cells were grown to 75% confluence, serum starved for 24 h, then treated with or without 5 ng/mL TGFβ for 1 h. ChIP was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using a kit from Cell Signaling Technologies. Rabbit IgG and SMAD2/3 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technologies) were used to pull down cross-linked DNA. Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified and analyzed via qRT-PCR using gene promoter-specific primers.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). Purified RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript II (Life Technologies), primed with OligodT (12–18) primers. Gene expression was assayed by qRT-PCR using the SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR green Mastermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). A cDNA standard curve was run for each primer set and sample expression was interpolated onto the curve, then normalized to GAPDH expression levels. Primer sequences are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Sequences of Oligonucleotides Used for qRT-PCR and ChIP PCR

| qRT-PCR | Sequence |

|---|---|

| PDGFbR FW | 5′ -TTCTCAGGCCACGATGAAAG-3′ |

| PDGFbR REV | 5′-GATCTTCAGCTCCGACATAAGG-3′ |

| EGFR FW | 5′-CAAGGAAGCCAAGCCAAATG-3′ |

| EGFR REV | 5′-CCGTGGTCATGCTCCAATAA-3′ |

| c-MET FW | 5′-CCACGGGACAACACAATACA-3′ |

| c-MET REV | 5′-TAAAGTGCCACCAGCCATAG-3′ |

| FGFR1 FW | 5′-CTTCCTGTCCAAACTCCATCC-3′ |

| FGFR1 REV | 5′-CAGCAGGTGGCAGAAGTAAA-3′ |

| IGF1R FW | 5′-TCTCTCTGGGAATGGGTCGT-3′ |

| IGF1R REV | 5′-CCTCCCACGATCAACAGGAC-3′ |

| PEPCK FW | 5′-TAGCACCCTCATCTGGGAATA-3′ |

| PEPCK REV | 5′-GTCTTTGTGGGAAGGTCTATGG-3′ |

|

| |

| ChIP | |

|

| |

| PDGFbR FW | 5′ -GGAAAGGAGAGCCAGAGAATG-3′ |

| PDGFbR REV | 5′-TCCCAAAGTGCTGGGATTAC-3′ |

| EGFR FW | 5′-GGTGGACTTGCCAAAGGAATA-3′ |

| EGFR REV | 5′-AGGAGAAATGCCAGGGAAAC-3′ |

| c-MET FW | 5′-CAGGCCGCGTTGTTTATTTAG-3′ |

| c-MET REV | 5′-GGAGAGTCACATAGCTGGTTAG-3′ |

| FGFR1 FW | 5′-CTCAACTCCCACTGCTTACTC-3′ |

| FGFR1 REV | 5′-GGAACTGGACCCTGTAAATTCT-3′ |

| IGF1R FW | 5′-CTGGTCTCCGCAGCATTTAT-3′ |

| IGF1R REV | 5′-CTAAGTCTCCGCGGTTGTTT-3′ |

Western Blotting

Cellular protein was extracted in a 1% NP40 cell lysis buffer with protease (Complete Mini; Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and phosphatase (PhosSTOP; Hoffman-La Roche) inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined via Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and samples were diluted in 2× Laemmli buffer with β-Mercaptoethanol (Sigma–Aldrich). Protein levels were measured using specific antibodies: (pSMAD2; catalogue number: 3108, pSMAD3; 9520, SMAD2/3; 8685, IGF1R; 9750, EGFR; 4267, c-Met; 8198, pIGF1R; 3021, AKT; 4685, pAKT; 4060, MCL1; 4572, Caspase 7; 9494, PARP; 9532 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and diluted 1:500 in inblocking buffer (5% nonfat milk in PBST), followed by 1:5000 IRDye680 anti-mouse and/or IRDye800 anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) in blocking buffer. Our β-Actin antibody was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich and β-Actin (catalogue number: A2228) was used for normalization of protein levels. Bands were quantified using ImageJ software [21].

Plasmids

The shScrambled and shIGF1R plasmids were constructed by inserting double stranded oligos into pGFP-V-RS plasmids (OriGene, Rockville, MD). Oligos were purchased from IDT (Coralville, Iowa). The oligo sequences were taken from the RNAi consortium(The Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA; IGF1R: 5′-GCTGT ACGTCTTCCATAGAAACTCGAGTTTCTATGGAAGA CGTACAGCTTTTT-3′, GFP: 5′-GACCACCCTGACCT ACGGCGTCTCGAGACGCCGTAGGTCAGGGTGGT CTTTTT-3′).

TCGA Analysis

Level 3 RNA-seqV2 expression data was downloaded from the TCGA database (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). The data in the TCGA database was generated using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform, and annotated based on the UCSC hg19 gene standard track. RNA expression values were quantified using the RSEM algorithm [22]. Data from 269 HCC patients, downloaded on 06/01/15 using the TCGA-assembler R package [23], were analyzed using the built in correlation test function in the R statistical software package.

Animal Study

Four-week-oldmale athymic nudeNODCB17-prkdc/SCIDmice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The tumor xenografts were established by inoculating 1.5 × 106 PLC/PRF/5 cells mixed with Matrigel into both flanks of mice. Treatments began 9 d after injections. LY2157299 (Selleckchem, Houston, TX) was dissolved in 50/50 Kollipher/95% EtOH solution and further diluted 1:4 in H2O in advance of each daily treatment. Each animal was administered 25mg/kg LY2157299 or vehicle, daily, via oral gavage. All animal studies were conducted according to the protocol approved by the Tulane Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistics

Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. Pearson, Spearman, and P values for correlations in TCGA datasets were performed using the R statistical package [24].

RESULTS

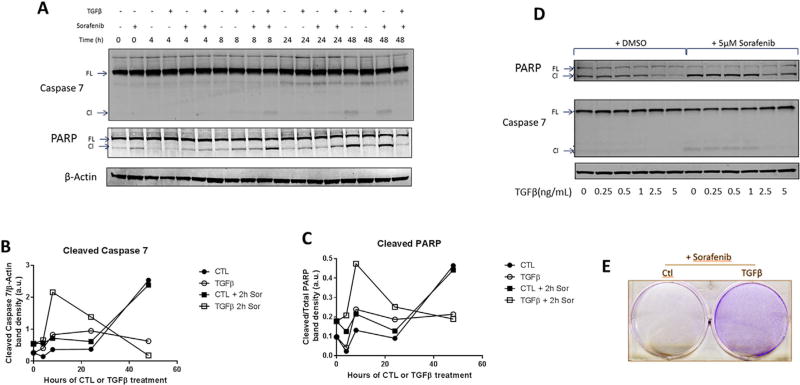

The Effect of TGFβ on HCC Cell Apoptosis, in the Presence or Absence of Sorafenib

TGFβ has an enigmatic role in HCC; it can either inhibit or promote tumor progression. To explore the dynamics of the cellular response to TGFβ signaling, we treated PLC/PRF/5 cells with 5 ng/mL of TGFβ1 for various lengths of time, ranging from 0 to 48 h and measured the effector caspase, caspase 7 (CAS7), and PARP levels at each time point (Figure 1A–C). For the first 24 h, TGFβ induced PARP and CAS7 cleavage. Interestingly, following 48 h of treatment, the TGFβ-treated cells exhibited reduced levels of PARP and CAS7 cleavage. To determine whether TGFβ could protect cells against the proapoptotic effect of sorafenib, the cells treated with or without TGFβ at each time point were incubated with 5 µM sorafenib for an additional 2 h period. We observed that at the 48 h time point, sorafenib was unable to efficiently induce PARP or CAS7 cleavage in TGFβ pretreated cells (Figure 1A–C). These findings suggest that sorafenib is less cytotoxic in tumor cells with persistently active TGFβ signaling. The dose of TGFβ was critical for the cytoprotective effect, as ≥2.5 ng/mL TGFβ was essential for the prevention of PARP and CAS7 cleavage in the presence or absence of sorafenib (Figure 1D). Accordingly, we observed that TGFβ pretreatment increased the survival of PLC/PRF/5 cells treated with sorafenib (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

The effect of TGFβ on cell survival. PLC/PRF/5 cells were treated with TGFβ1 and/or sorafenib as indicated. (A–C) The cells were treated with 5 ng/mL TGFβ1 for up to 48 h, followed by 2 h of 5 µM sorafenib or vehicle, and lysates were obtained for immunoblotting (A) and quantified using ImageJ software (B, C). (D) Immunoblot of cells treated with 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, or 5 ng/mL TGFβ for 48 h then with 5 µM sorafenib or vehicle for 2 h. (E) Crystal violet stain of cells seeded at 2 × 105 cells per 3.5 cm well, treated with 5 ng/mL TGFβ for 48 h, then 5 µM sorafenib for 24 h.

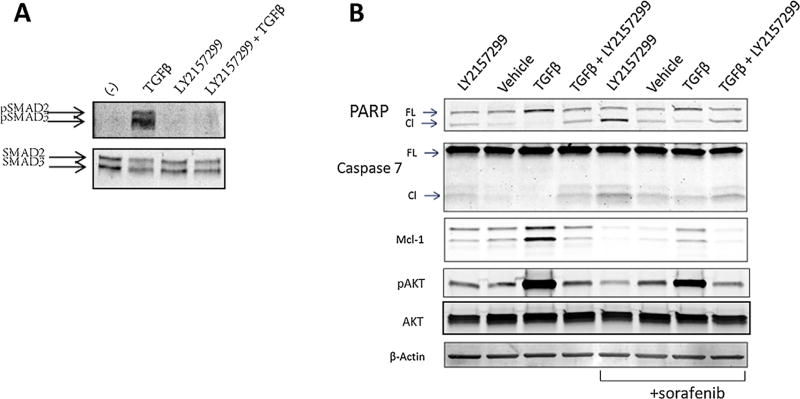

Sorafenib-Induced HCC Apoptosis Is Enhanced by the TGFβRI Inhibitor, LY2157299

The observed protective effect of TGFβ against sorafenib-induced HCC cell apoptosis suggests that inhibition of the TGFβ signaling pathway may be of therapeutic value for HCC. To test this possibility, we utilized LY2157299 (galunisertib), a small molecule TGFβRI kinase inhibitor currently being investigated in HCC clinical trials [25]. This inhibitor has shown promise in preclinical models and we confirm it was able to reduce tumor burden in immunocompromised mice (Figure S1). After verification that LY2157299 inhibits TGFβ signaling in PLC/PRF/5 cells (Figure 2A), we treated the cells with LY2157299 in the presence or absence of TGFβ for 48 h, followed by a 2 h incubation with sorafenib or vehicle control. Consistent with TGFβ-mediated cell survival, we observed that inhibition of TGFβ signaling by LY2157299 led to cell apoptosis, as reflected by increased CAS7 and PARP cleavage (Figure 2B). These results were similar but heightened in cells that were further treated with sorafenib (Figure 2B). As sorafenib targets RAF and inhibits the MAPK signaling pathway [15], we reasoned that other pro-survival molecule(s) may be activated by TGFβ that confer resistance to sorafenib-induced apoptosis. Interestingly, we observed high levels of activated AKT in cells treated with TGFβ (Figure 2B), which suggests that TGFβ may activate AKT, rendering cells resistant to sorafenib-induced cytotoxicity. The latter assertion is further corroborated by the fact that TGFβ is known to activate the PI3K-AKT cascade [26], a crucial signaling pathway for cell survival [27].

Figure 2.

TGFβR1 kinase inhibitor, LY2157299, enhances sorafenib-induced apoptosis in PLC/PRF/5 cells. (A) The cells were lysed and immunoblotted after incubation with either 5 µM LY2157299 or vehicle for 1 h, followed by 5 ng/mL TGFβ or vehicle for 1 h. (B) The cells were lysed and immunoblotted following treatment for 48 h with 5 µM LY2157299, vehicle, 5 ng/mL TGFβ or both LY2157299 and TGFβ for 48 h then with either 5 µM sorafenib or vehicle for 2 h.

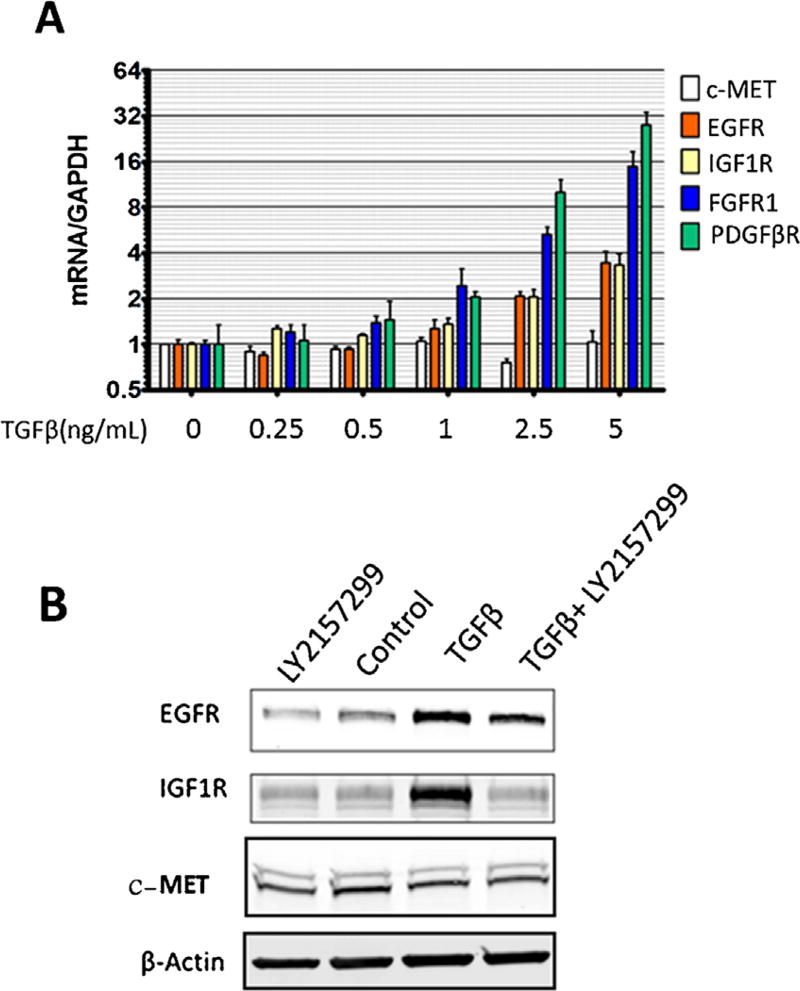

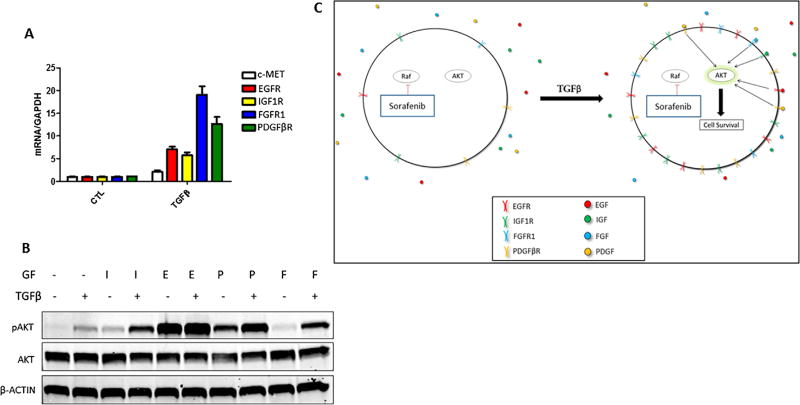

TGFβ Treatment Leads to Increased RTK Levels

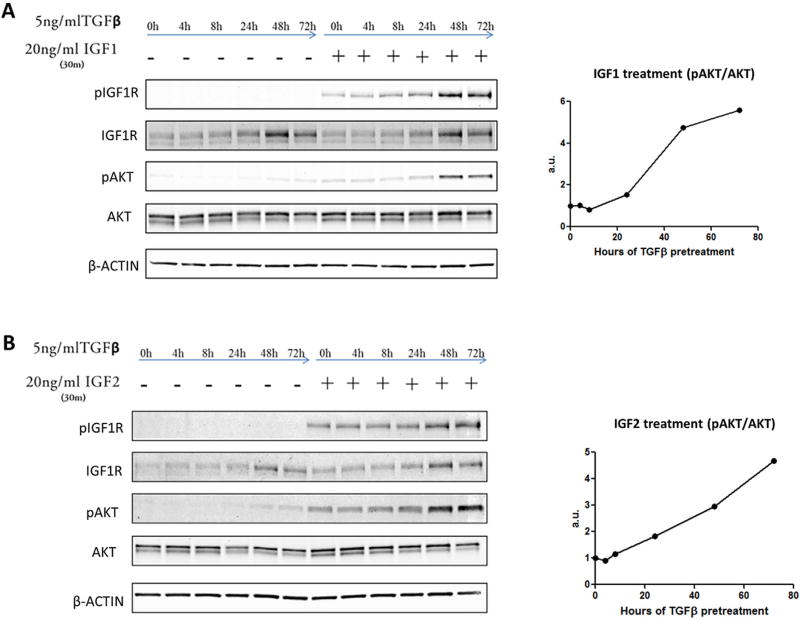

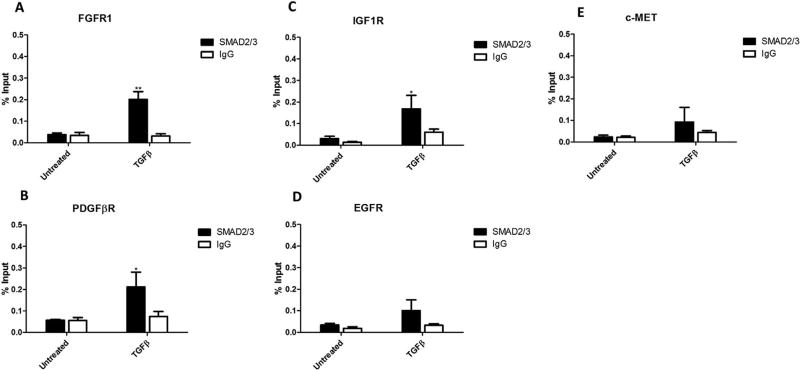

We observed that AKT phosphorylation peaked following 48 h of TGFβ treatment (see below, Figure 6A), whereas activation of canonical TGFβ signaling proteins, SMAD2 and SMAD3, peak at 1 h in PLC/PRF/5 cells [28]. The substantial time lag between TGFβ treatment and AKT phosphorylation suggests that TGFβ may influence AKT activity through regulation of other signaling molecules. Given that PDGFβR is a known TGFβ regulated gene that is functionally upstream of AKT [29,30], we measured the expression levels of PDGFβR, as well as several other RTKs currently being targeted for HCC therapy in clinical trials. We observed that TGFβ treatment led to an increase in the mRNA expression of PDGFβR, FGFR1, EGFR, and IGF1R, but not c-MET in PLC/PRF/5 cells (Figure 3A), Hep3B cells (Figure S2), and Huh7 cells (see below, Figure 8A). While both PDGFβR and FGFR1 proteins were undetectable, even following TGFβ treatment (data not shown), EGFR and IGF1R proteins were upregulated by TGFβ (Figure 3B). Next, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay to determine SMAD2/3 association with the promoter regions of the RTKs. Our data showed that TGFβ treatment significantly increased SMAD2/3 binding to the promoter regions of FGFR1 (Figure 4A), PDGFβR (Figure 4B), and IGF1R (Figure 4C), suggesting SMAD2/3-mediated transcription for induction of these RTKs. While TGFβ treatment slightly increased SMAD2/3 association with the EGFR and c-MET promoters, the effect was not statistically significant.

Figure 6.

TGFβ increases cell sensitivity to IGF ligands by increasing IGF1R expression. PLC/PRF/5 cells were treated for up to 72 h with 5 ng/mL TGFβ, then followed with either control medium or 20 ng/mL IGF1 (A) or IGF2 (B) for 30 min. The cells were then lysed and the cellular proteins were subjected to immunoblotting. ImageJ densitometry analysis was performed to determine pAKT band density (normalized to total AKT).

Figure 3.

TGFβ increases the expression of several receptor tyrosine kinases. (A) mRNA expression in PLC/PRF/5 cells treated with 0–5 ng/mL TGFβ for 48 h. Data are presented as mean±SEM, n=3 biological replicates. (B) Protein levels of PLC/PRF/5 cells treated with 5 ng/mL TGFβ for 48 h.

Figure 8.

TGFβ increases cell sensitivity to multiple growth factors in Huh7 cells. (A) mRNA expression of Huh7 cells treated with 5 ng/mL TGFβ for 48 h. Data are presented as mean±SEM, N=3 biological replicates. (B) Immunoblot of Huh7 cell lysates after cells were treated with 5 ng/mL TGFβ for 48 h, then 20 ng/mL of IGF, EGF, PDGFβ, or FGF1 for 30 min. (C) Proposed model of TGFβ/RTKs/Akt signaling pathways for sorafenib resistance in HCC.

Figure 4.

TGFβ treatment induces SMAD2/3 binding to PDGFβR, FGFR1, and IGF1R promoter regions. PLC/PRF/5 cells treated with or without 5 ng/mL TGFβ for 1 h were fixed and subjected to ChIP assay using a SMAD2/3 antibody (with rabbit IgG as control). The promoter regions of PDGFβR (A), FGFR1 (B), IGF1R (C), EGFR (D), and c-MET (E) were amplified and analyzed by qRT-PCR. Results were plotted as a percentage of input DNA from either control or TGFβ treated cells. Data are presented as mean±SEM. N=3 biological replicates, *P<0.05; **P<0.01 by Student's t-test (compared to untreated cells).

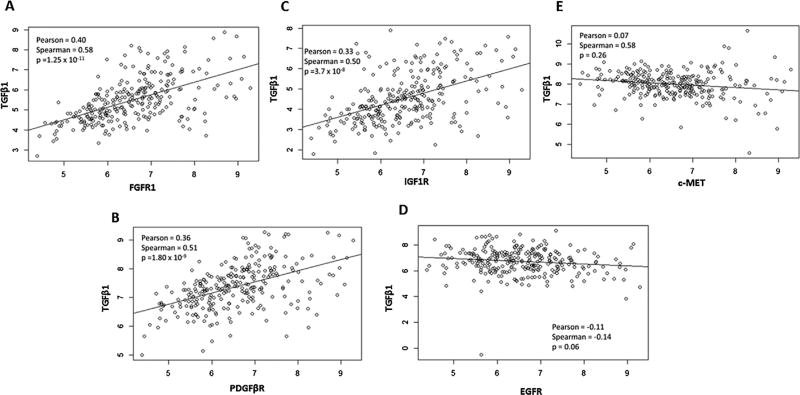

We next analyzed HCC patient RNA-SeqV2 datasets available from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). Notably, of the RTKs upregulated by TGFβ, FGFR1, IGF1R, and PDGFβR are positively correlated with TGFβ1 in patient tumors (Figure 5A–E). These findings provide important clinical evidence in support of the interaction between TGFβ and receptor tyrosine kinases pathways in human HCC.

Figure 5.

Analysis of TCGA datasets reveal that TGFβ expression levels correlate with RTKs in human HCCs. RNASeqV2 mRNA expression data from tumors of HCC patients were extracted from The Cancer Genome Atlas (http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). Each data point represents a single patient tumor, with TGFβ1 and the listed RTK expression level represented on the y- and x-axis, respectively. Correlation analysis using the R software package was performed to test for association between paired samples. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, and P-values are listed for each plot. Statistically significant (P<0.05) correlation was found between TGFβ1 and FGFR1(A), PDGFβR (B), and IGF1R (C), but not between TGFβ1 and EGFR (D), or c-MET (E) mRNA expression levels.

TGFβ Treatment Promotes HCC Cell Survival by Sensitizing Cell Response to IGF1R Ligands

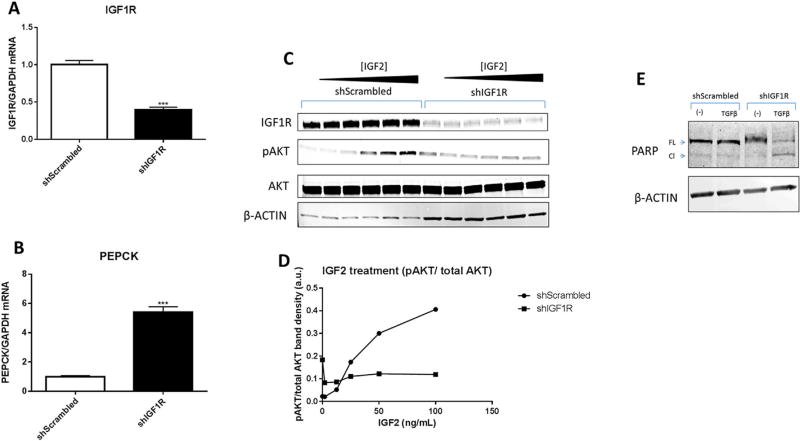

Because FGFR1 and PDGFβR protein levels were undetectable in PLC/PRF/5 cells, and EGFR did not correlate with TGFβ in patient samples, we next focused on the IGF signaling pathway in the subsequent experiments. We observed that TGFβ treatment increased IGF1R protein levels in a time dependent manner (Figure 6A, B). To determine whether the cells with elevated IGF1R levels show enhanced sensitivity to the IGF1R ligands (IGF1 and IGF2), we further treated TGFβ-incubated cells with IGF1 or IGF2. Specifically, the cells with or without TGFβ treatment for different time periods were incubated with IGF1 or IGF2 for an additional 30 min and AKT phosphorylation was measured. We observed that TGFβ treatment sensitized the cells to IGF1 and IGF2-induced AKT phosphorylation (Figure 6A–D). The enhanced sensitivity followed the upregulation of IGF1R protein and was dependent on IGF1 or IGF2 as evidenced by lack of IGF1R phosphorylation following 48 h TGFβ treatment alone. Interestingly, the most dramatic increase in IGF1R protein levels and IGF sensitivity took place between the 24 and 48 h time points following TGFβ treatment, which is concurrent with the time points that TGFβ switched from a proapoptotic to a prosurvival signaling molecule (Figure 1A–C). To determine whether IGF signaling was essential for the antiapoptotic effect of TGFβ, we stably knocked down IGF1R using a shRNA construct (Figure 7A, C). As expected, the cells with shRNA knockdown of IGF1R were no longer responsive to IGF (Figure 7C, D). This was further evidenced by an approximately fivefold increase in the expression of phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK; Figure 7B), a gene normally repressed by IGF signaling [31]. Accordingly, we observed that treatment of IGF1R knockdown cells with TGFβ led to apoptosis (Figure 7E). These findings suggest that IGF1R is necessary for the TGFβ-mediated prosurvival effect.

Figure 7.

IGF1R is necessary for TGFβ-mediated prevention of apoptosis. (A, B) mRNA was quantified from PLC/PRF/5 shScrambled and shIGF1R stable cell lines. Data are presented as mean±SEM, with N= 3 biological replicates, ***P<0.001, Student's t-test (compared to shScrambled). (C, D) Immunoblot and densitometry of lysates from shScrambled and shIGF1R PLC/PRF/5 cells treated with 0–100 ng/mL of IGF2 for 30 min. (E) Immunoblot of PLC/PRF/5 cell lysates after the cells were treated with 5 ng/mL TGFβ or control medium for 48 h.

TGFβ Primes Huh7 Cells to Various RTK Activating Stimuli

Due to undetectable levels of PDGFβR and FGFR1 in PLC/PRF/5 cells, these cells provided a simplistic system to study the consequences of TGFβ-mediated sensitization to one family of RTK ligands (IGF1/2). However, HCCs are characteristically heterogeneous and the array of overexpressed RTKs can differ greatly from patient to patient. To further determine whether sensitization of RTKs by TGFβ may be a generalized mechanism in HCC cells, we utilized a different HCC cell line, Huh7. Huh7 cells express threefold higher basal PDGFβR and sevenfold higher basal FGFR1 as compared to PLC/PRF/5 cells (data not shown), along with comparable IGF1R and EGFR. We observed that treatment of Huh7 cells with TGFβ for 48h significantly increased IGF1R, EGFR, PDGFβR, and FGFR1 mRNA levels (Figure 8A). In these cells, the elevation of these RTK levels sensitized the cells to IGF, PDGFβ, and FGF1, as reflected by enhanced AKT phosphorylation (Figure 8B). Taken together, our findings suggest that TGFβ can upregulate the expression of multiple RTKs, leading to enhanced AKT activation by cognate ligands in HCC cells (illustrated in Figure 8C).

DISCUSSION

While TGFβ has been shown to prevent early stage tumorigenesis, following tumor initiation, TGFβ can act in many ways to promote tumor progression. As an example, TGFβ has been extensively studied for its role in the epithelial mesenchymal transition [32], its impact on cancer stemness and tumor initiating cells [33], and its subsequent promotion of metastasis [34]. TGFβ has also been implicated in promoting sorafenib resistance through CD44 as a mesenchymal-like phenotype [35]. In the current study, we present a novel mechanism by which TGFβ contributes to hepatocellular cancer progression by priming cells to survival signals, allowing cells to evade apoptosis, even in the presence of the chemotherapeutic agent, sorafenib. Our gene expression profile analysis shows a strong association between TGFβ1 and several key RTKs, including IGF1R, PDGFβR, and FGFR1, in human liver tumor tissue. Given the progressive activation of the TGFβ signaling pathway during the hepatocarcinogenic process, the abundance and diversity of RTKs induced by TGFβ may represent an important mechanism by which HCC tumors progress and circumvent sorafenib induced cell death.

During the multistage carcinogenic processes, upregulation of RTKs provide tumor cells the ability to survive and proliferate in various microenvironments rich in RTK ligands [36]. While inhibiting specific RTKs has achieved therapeutic efficacy against a number of human cancers, such a strategy has been largely disappointing for HCC. To date, several HCC clinical trials targeting RTKs, such as those targeting IGF1R [37], EGFR [38], or FGFR [39] have led to unsatisfactory results, leaving sorafenib as the only FDA approved systemic therapy for HCC patients. However, many HCC patients develop resistance to sorafenib, and the exact mechanisms for tumor cell resistance to this multikinase inhibitor are not fully understood. In the present study, we provide novel evidence that TGFβ induces the expression of several RTKs, in turn priming HCC cells to respond to a variety of different RTK ligands, a mechanism that may play an important role in the development of sorafenib resistance.

Sorafenib resistance in HCC has been attributed to overactive IGF1R [40] and EGFR [41] signaling pathways. In our system, we show that expression levels of IGF1R and EGFR, as well as PDGFβR and FGFR1, are upregulated by TGFβ. Our findings suggest a potential role for TGFβ-regulated RTKs in HCC resistance to sorafenib therapy. The implication of our findings are further corroborated by the observations that the levels of TGFβ are increased in HCC patients [42] and that even higher levels of TGFβ are found in patients that do not respond to sorafenib treatment [43]. A recent study has shown a synergistic anti-tumor effect between sorafenib and LY2157299 in an ex vivo model of HCC [44], although the mechanism for such synergism was not clearly defined. Preclinical studies of the effect of another TGFβ signaling pathway inhibitor has demonstrated efficacy in reducing HCC tumor burden by inhibiting tumor cell-stroma cross-talk [45]. In the current study we show that blocking TGFβ signaling by LY2157299 prior to sorafenib treatment was able to effectively prevent AKT activation and induce apoptosis, in vitro. Our findings provide important mechanistic explanation and justify targeting the TGFβ signaling pathway in conjunction with other anti-tumor therapies (such as sorafenib and RTK inhibitors) for more effective treatment of human HCC.

In PLC/PRF/5 cells, where PDGFBR and FGFR1 were undetectable at the protein level, IGF1R was necessary for the TGFβ mediated effect on sorafenib resistance. However, consistent with the functional redundancy in RTK signaling pathways [46], a significant clinical problem for RTK-targeted therapies is that inhibition of only one receptor often leads to the upregulation of another similar RTK. This aspect is highlighted by a recent study demonstrated that inhibition of cell proliferation by targeting one particular RTK in a panel of 41cell lines could be reversed by the activation of a separate RTK [47]. Our experimental findings in the current study suggest that TGFβ-mediated induction of multiple RTKs may allow tumor cells to escape therapies that target individual RTKs.

In summary, the current study reveals an important interplay between TGFβ and RTK signaling pathways which are crucial for hepatocellular cancer cell survival and resistance to therapy. Our findings provide important molecular basis for further clinical studies to assess the efficacy of targeting the TGFβ signaling pathway to overcome sorafenib resistance and/or to develop new effective combination therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant numbers: DK077776; CA102325

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

References

- 1.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakin AV, Tomlinson AK, Bhowmick NA, Moses HL, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36803–36810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartsough MT, Mulder KM. Transforming growth factor beta activation of p44mapk in proliferating cultures of epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7117–7124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts AB, Anzano MA, Wakefield LM, Roche NS, Stern DF, Sporn MB. Type beta transforming growth factor: A bifunctional regulator of cellular growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:119–123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark RA, McCoy GA, Folkvord JM, McPherson JM. TGF-beta 1 stimulates cultured human fibroblasts to proliferate and produce tissue-like fibroplasia:A fibronectin matrix-dependent event. J Cell Physiol. 1997;170:69–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199701)170:1<69::AID-JCP8>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell WE. Tr ansforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) inhibits hepatocyte DNA synthesis independently of EGF binding and EGF receptor autophosphorylation. J Cell Physiol. 1988;135:253–261. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041350212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberhammer FA, Pavelka M, Sharma S, et al. Induction of apoptosis in cultured hepatocytes and in regressing liver by transforming growth factor beta 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5408–5412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichl P, Haider C, Grubinger M, Mikulits W. TGF-beta in epithelial to mesenchymal transition and metastasis of liver carcinoma. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:4135–4147. doi: 10.2174/138161212802430477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu K, Ding J, Chen C, et al. Hepatic transforming growth factor beta gives rise to tumor-initiating cells and promotes liver cancer development. Hepatology. 2012;56:2255–2267. doi: 10.1002/hep.26007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulouarn C, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS. Transforming growth factor-beta gene expression signature in mouse hepatocytes predicts clinical outcome in human cancer. Hepatology. 2008;47:2059–2067. doi: 10.1002/hep.22283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oshimori N, Oristian D, Fuchs E. TGF-beta promotes heterogeneity and drug resistance in squamous cell carcinoma. Cell. 2015;160:963–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L, Cao Y, Chen C, et al. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11851–11858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen KF, Chen HL, Tai WT, et al. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway mediates acquired resistance to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:155–161. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudek H, Datta SR, Franke TF, et al. Regulation of neuronal survival by the serine-threonine protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;275:661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kauffmann-Zeh A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Ulrich E, et al. Suppression of c-Myc-induced apoptosis by Ras signalling through PI(3)K and PKB. Nature. 1997;385:544–548. doi: 10.1038/385544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llovet JM, Villanueva A, Lachenmayer A, Finn RS. Advances in targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma in the genomic era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;7:408–424. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li B, Ruotti V, Stewart RM, Thomson JA, Dewey CN. RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:493–500. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Y, Qiu P, Ji Y. TCGA-assembler: Open-source software for retrieving and processing TCGA data. Nat Methods. 2014;11:599–600. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.RC Team. R. A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013 From http://www.R-project.org/

- 25.Rodon J, Carducci MA, Sepulveda JM, et al. Integrated data review of the first-in-human dose (FHD) study evaluating safety, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics (PD) of the oral transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-ss) receptor I kinase inhibitor, LY2157299 monohydrate (LY) J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2013;31:2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horowitz JC, Lee DY, Waghray M, et al. Activation of the prosurvival phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway by transforming growth factor-beta1 in mesenchymal cells is mediated by p38 MAPK-dependent induction of an autocrine growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1359–1367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306248200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franke TF, Hornik CP, Segev L, Shostak GA, Sugimoto C. PI3K/Akt and apoptosis: Size matters. Oncogene. 2003;22:8983–8998. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dzieran J, Fabian J, Feng T, et al. Comparative analysis of TGF-beta/Smad signaling dependent cytostasis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinzani M, Gentilini A, Caligiuri A, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta subunit in human liver fat-storing cells. Hepatology. 1995;21:232–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer AN, Fuchs E, Mikula M, Huber H, Beug H, Mikulits W. PDGF essentially links TGF-beta signaling to nuclear betacatenin accumulation in hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Oncogene. 2007;26:3395–3405. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granner D, Andreone T, Sasaki K, Beale E. Inhibition of transcription of the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene by insulin. Nature. 1983;305:549–551. doi: 10.1038/305549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giannelli G, Koudelkova P, Dituri F, Mikulits W. Role of epithelial to mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2016;65:798–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fabregat I, Malfettone A, Soukupova J. New insights into the crossroads between EMT and stemness in the context of cancer. J Clin Med. 2016;5 doi: 10.3390/jcm5030037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsuno Y, Lamouille S, Derynck R. TGF-beta signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer progression. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:76–84. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835b6371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fernando J, Malfettone A, Cepeda EB, et al. A mesenchymal-like phenotype and expression of CD44 predict lack of apoptotic response to sorafenib in liver tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E161–E172. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Nie D, Chakrabarty S. Growth factors in tumor microenvironment. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2010;15:151–165. doi: 10.2741/3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abou-Alfa GK, Capanu M, O'Reilly EM, et al. A phase II study of cixutumumab (IMC-A12, NSC742460) in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;60:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu AX, Stuart K, Blaszkowsky LS, et al. Phase 2 study of cetuximab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;110:581–589. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson PJ, Qin S, Park JW, et al. Brivanib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy in patients with unresectable, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Results from the randomized phase III BRISK-FL study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3517–3524. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Y, Huang J, Ma L, et al. MicroRNA-122 confers sorafenib resistance to hepatocellular carcinoma cells by targeting IGF-1R to regulate RAS/RAF/ERK signaling pathways. Cancer Lett. 2016;371:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ezzoukhry Z, Louandre C, Trecherel E, et al. EGFR activation is a potential determinant of primary resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells to sorafenib. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2961–2969. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sacco R, Leuci D, Tortorella C, et al. Transforming growth factor beta1 and soluble Fas serum levels in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cytokine. 2000;12:811–814. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin TH, Shao YY, Chan SY, Huang CY, Hsu CH, Cheng AL. High serum transforming growth factor-beta1 levels predict outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3678–3684. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serova M, Tijeras-Raballand A, Dos Santos C, et al. Effects of TGF-beta signalling inhibition with galunisertib (LY2157299) in hepatocellular carcinoma models and in ex vivo whole tumor tissue samples from patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6:21614–21627. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mazzocca A, Fransvea E, Dituri F, Lupo L, Antonaci S, Giannelli G. Down-regulation of connective tissue growth factor by inhibition of transforming growth factor beta blocks the tumor-stroma cross-talk and tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;51:523–534. doi: 10.1002/hep.23285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141:1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson TR, Fridlyand J, Yan Y, et al. Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors. Nature. 2012;487:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.