Abstract

Objective

To determine the association between patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and 30-day potentially preventable hospital readmissions. A secondary objective was to examine the conditions resulting in these potentially preventable readmissions.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Inpatient rehabilitation facilities submitting claims to Medicare.

Participants

National cohort of 371,846 inpatient rehabilitation discharges among aged Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in 2013–2014. The average age was 79.1 (SD, 7.6) years. A majority were female (59.7%) and non-Hispanic white (84.5%).

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

1) Observed rates and adjusted odds of 30-day potentially preventable hospital readmissions following inpatient rehabilitation and 2) primary diagnoses for readmissions.

Results

The overall rate of any 30-day hospital readmission following inpatient rehabilitation was 12.4% (N=46,265) and the overall rate of potentially preventable readmissions was 5.0% (N=18,477). Functional independence was associated with lower observed rates and adjusted odds ratios for potentially preventable readmissions. Observed rates (95% CI) for the highest vs. lowest quartiles within each functional domain were as follows: self-care: 3.4% (3.3–3.5) vs 6.9% (6.7–7.1); mobility: 3.3% (3.2–3.4) vs 7.2% (7.0–7.4); cognition 3.5% (3.4–3.6) vs 6.2% (6.0–6.4). Similarly, adjusted odds ratios were as follows: self-care: 0.70 (0.67–0.74); mobility: 0.64 (0.61–0.68); cognition: 0.84 (0.80–0.89). Infection-related conditions (44.1%) were the most common readmission diagnoses followed by inadequate management of chronic conditions (31.2%) and inadequate management of other unplanned events (24.7%).

Conclusions

Functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation was associated with 30-day potentially preventable readmissions in our sample of aged Medicare beneficiaries. This information may help identify at-risk patients. Future research is needed to determine whether follow-up programs focused on improving functional independence will reduce readmission rates.

Keywords: quality of care, post-acute care, self-care, mobility limitation, cognitive function

The Improving Medicare Post-acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT Act) mandates the development of standardized quality and resource use measures for postacute care settings.1 These measures reflect a shift from rewarding volume of postacute services to rewarding value of postacute services. One of the resource use measures recently adopted to meet the requirements of the IMPACT Act is the Potentially Preventable 30-Day Post-Discharge Readmission Measure for Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Quality Reporting Program.1,2 This metric was implemented October 1, 2016 and public reporting will begin in 2018.2

Another recently adopted measure is the Potentially Preventable Within Stay Readmission Measure for Inpatient Rehabilitation Facilities.2 This measure holds providers accountable for potentially preventable readmissions occurring during inpatient rehabilitation, the day of discharge, or the day following discharge. The post-discharge measure starts when the within stay one ends and holds providers accountable for readmissions occurring over the next 30 days (i.e., days 2 to 32 post-discharge).2 The conceptual definition of “potentially preventable” used for both measures is as follows, “For certain diagnoses, proper care and management of patients’ conditions (in the facility or by primary care following discharge) along with appropriate, clearly explained and implemented discharge instructions and referrals, can often prevent a patient’s readmission to the hospital.”3 p23 The recent adoption of these two measures highlights the growing emphasis on readmissions considered “potentially preventable”. By definition, potentially preventable readmissions imply a clinically appropriate target for improvement.

Demonstrating that postacute care is a valuable component of the continuum of care following illness or injury is important as payment reforms, such as episode-based payment models, are implemented. Hospitals are increasingly incentivized to contain costs over extended episodes of care (e.g. 90 days), and spending on postacute care has been identified as a target for cost-saving.4,5 Inpatient rehabilitation care is costly.6 In 2015, the average cost per case in this setting was over $19,000.7 Under episode-based payment models, hospitals will be financially motivated to discharge patients to the most cost-effective postacute setting. Inpatient rehabilitation facilities will need to prove that this level of care leads to better long-term outcomes and less downstream spending. Low post-discharge hospital readmission rates may help demonstrate the value of care provided in this setting.

Understanding the risk factors associated with potentially preventable readmissions, as well as the conditions resulting in these readmissions, can help inform prevention efforts. Because patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation is associated with 30-day unplanned readmissions,8 we hypothesized that functional status would also be associated with 30-day potentially preventable readmissions. Understanding the relationship between discharge functional status and potentially preventable readmissions could have implications for inpatient rehabilitation care-delivery, discharge planning, and care transitions. The primary objective of our study was to determine the association between patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and 30-day potentially preventable readmissions. We used the hospital readmission diagnoses included in the Potentially Preventable 30-Day Post-Discharge Readmission Measure for the Inpatient Rehabilitation Quality Reporting Program, but did not replicate the measure. We categorized functional status into three domains, self-care, mobility, and cognition. The association may vary across the domains, and this information will help guide targeted prevention efforts. To further guide these efforts, a secondary objective of our study was to examine the conditions resulting in potentially preventable readmissions.

Methods

Data Sources

The study was approved by the University Institutional Review Board. We obtained CMS data after establishing a Data Use Agreement. We used the following 100% Medicare files from 2012–2014: Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI), Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR), and Beneficiary Summary. IRF-PAI files contain assessment records for inpatient rehabilitation stays. This information is submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and used to determine payment under the fee-for-service prospective payment system.9 We used IRF-PAI files to extract information on patients’ rehabilitation impairment group and functional status. MedPAR files contain final claims for all Medicare fee-for-service inpatient stays, including acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities, long-term acute care hospitals, and psychiatric hospitals.10 We extracted information on acute care hospitalizations prior to, during, and following inpatient rehabilitation from these files. Finally, we extracted sociodemographic and enrollment (i.e. fee-for-service versus Medicare Managed Care) information from Beneficiary Summary files.11 MedPAR, IRF-PAI, and Beneficiary Summary files were linked using encrypted unique beneficiary identification numbers.

Study Cohort

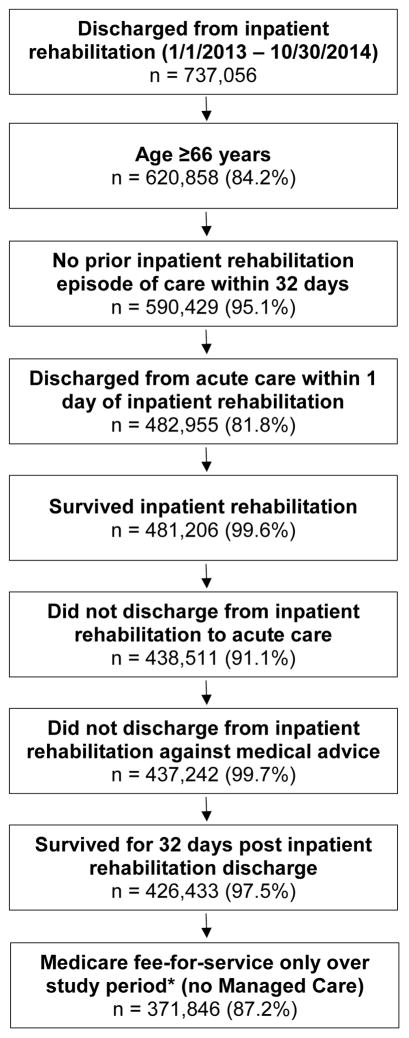

The population of interest was aged Medicare beneficiaries discharged from inpatient rehabilitation. Cohort selection is presented in Figure 1. We included all discharges occurring between January 1, 2013 and October 30, 2014 (N=737,056). To be conservative, we did not include discharges after October 30th, as readmissions occurring at the end of the post-inpatient rehabilitation observation window and lasting longer than 28 days would not be included in the 2014 claims files. We restricted age to 66 years and older, so that we would have claims data for a six month look back on all included beneficiaries. Patients could have multiple inpatient rehabilitation stays over the study period. To ensure we did not include rehabilitation stays in the post-discharge observation window of another included stay, we excluded cases with a rehabilitation discharge in the prior 32 days. Our focus was patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation immediately following a hospitalization, so we excluded patients without a hospital stay within one day of inpatient rehabilitation admission. Per specifications of the 30-day potentially preventable readmission measure, we excluded inpatient rehabilitation stays for patients who discharged directly to the hospital.3 We did not exclude those discharged to other non-acute care settings (e.g., skilled nursing facilities). We also excluded patients who discharged against medical advice, and those who did not survive their rehabilitation stay and 32 days following discharge. Finally, we excluded patients who were in Medicare Managed Care at any point over the six months prior to or 32 days following inpatient rehabilitation, as we would not have claims data during these periods. The final cohort included 371,846 inpatient rehabilitation discharges.

Figure 1.

Flow chart presenting number of eligible cases remaining at each step as exclusion criteria applied. Percentages are percent remaining from the previous step. * ‘Study period’ refers to the 6 months prior to the index hospitalization though the 32 days post-discharge for each inpatient rehabilitation stay.

Outcome

The primary outcome was 30-day potentially preventable hospital readmissions following inpatient rehabilitation (dichotomous, yes/no). We used the list of diagnoses (ICD-9 codes) included in the Potentially Preventable 30-Day Post-Discharge Readmission Measure for the Inpatient Rehabilitation Quality Reporting Program.3 Diagnoses were grouped into the following categories by measure developers: inadequate management of infection (e.g. septicemia, urinary tract infection), inadequate management of chronic conditions (e.g. heart failure, obstructive bronchitis), and inadequate management of other unplanned events (e.g. kidney failure, atrial fibrillation).3 The 30-day observation window for the measure is days 2 through 32 post-inpatient rehabilitation discharge.3 We used this window and reviewed MedPAR claims to determine whether or not a patient was readmitted, and if so, whether the readmission diagnosis was on the list for the potentially preventable quality measure.

Functional Status

The predictor of interest was patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Functional status is assessed at admission and discharge as part of the larger IRF-PAI.9 The functional data elements collected are the 18 items from the Functional Independence Measure (FIM). Patients’ level of independence on each item is rated on a 7-point scale. Higher scores indicate greater independence and lower burden of care. We created self-care, mobility, and cognition functional domains.12 The self-care domain included six items related to eating, grooming, bathing, dressing-upper body, dressing-lower body, and toileting (score range 6–42). The mobility domain included five items related to transfers, walking/wheelchair mobility, and ability to climb stairs (score range 5–35). The cognition domain included five items related to comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem solving, and memory (score range 5–35).9 The remaining two items from the FIM are related to bowel and bladder management. We included discharge status on these items as covariates in the multivariable analyses.

Covariates

We extracted the following sociodemographic information from Beneficiary Summary files: age, sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or Other), disability entitlement (disability the original reason for Medicare eligibility, yes/no), and dual eligibility (eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, yes/no). We defined the hospitalization immediately preceding inpatient rehabilitation as the “index hospitalization”. We reviewed MedPAR claims to determine the number of hospitalizations over the six months prior to the index hospitalization and to gather information on the index hospitalization, including primary diagnosis (ICD-9), length of stay (days), intensive care or coronary care unit utilization (ICU/CCU, yes/no), and comorbid conditions. We grouped hospital diagnoses into the clinically meaningful Clinical Classification Software (CCS) multi-level diagnostic categories developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project.13 We used the Elixhauser comorbidity measure to identify comorbidities present during the index acute care hospitalization. The comorbidities included in this measure represent diagnoses secondary to the admitting diagnosis that may impact healthcare utilization and/or mortality.14 We also used claims in the MedPAR file to identify program interruptions during inpatient rehabilitation (yes/no). Program interruptions are defined by CMS as temporary (i.e. ≤3 days) transfers from the inpatient rehabilitation facility to another setting (e.g., hospital, community), with the patient returning to continue rehabilitation.9

Data Analysis

We calculated observed rates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) of 30-day potentially preventable readmissions for the overall sample and by patient characteristic. To examine the association between patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and 30-day potentially preventable readmissions, we constructed a multilevel logistic regression model (PROC GLIMMIX in SAS software). Multilevel logistic regression allowed us to estimate a dichotomous outcome (potentially preventable readmission, yes/no) while accounting for the clustering of patients within inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Due to multicollinearity between self-care and mobility scores when both were included in the model, we estimated separate models for each with cognition scores and the following covariates: age; sex; race/ethnicity; disability entitlement; dual eligibility; number of hospitalizations over prior six months; number of comorbidities; index hospitalization diagnostic category, length of stay, and ICU/CCU utilization; and inpatient rehabilitation admission impairment group, program interruption, and bowel/bladder management score. We categorized performance on the functional domains into lowest quartile, interquartile range, and highest quartile for analyses. To examine how different combinations of discharge self-care and mobility functional status (e.g., patients in top quartile for self-care and bottom quartile for mobility) impacted 30-day potentially preventable readmission rates, we also calculated rates for all combinations of performance across the self-care and mobility domains. We used IBM® SPSS 23a and SAS version 9.4b software for all analyses.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

The average age of the cohort was 79.1 (SD, 7.6) years. A majority were female (59.7%) and non-Hispanic white (84.5%). Cohort characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Observed rates of potentially preventable 30-day readmissions following inpatient rehabilitation

| Overall Sample n=371,846 |

Observed Rate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 18,477 | 5.0% (4.9, 5.1) |

| Age, years | ||

| <75 | 117,961 | 4.1% (4.0, 4.2) |

| 75–84 | 152,631 | 5.1% (5.0, 5.2) |

| >84 | 101,254 | 5.9% (5.8, 6.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 221,929 | 4.6% (4.5, 4.7) |

| Male | 149,917 | 5.4% (5.3, 5.5) |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 314,101 | 5.0% (4.9, 5.1) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 29,023 | 5.4% (5.1, 5.7) |

| Hispanic | 18,159 | 5.1% (4.8, 5.4) |

| Other | 9,595 | 3.5% (3.1, 3.9) |

| Disability entitlement† | ||

| No | 326,065 | 4.8% (4.7, 4.9) |

| Yes | 45,781 | 6.1% (5.9, 6.3) |

| Dual eligibility‡ | ||

| No | 316,421 | 4.7% (4.6, 4.8) |

| Yes | 55,425 | 6.2% (6.0, 6.4) |

| Prior hospitalizations | ||

| 0 | 269,054 | 3.8% (3.7, 3.9) |

| 1 | 70,876 | 6.7% (6.5, 6.9) |

| 2 | 21,216 | 9.6% (9.2, 10.0) |

| 3+ | 10,700 | 14.0% (13.3, 14.7) |

| CCS Diagnostic category§ | ||

| Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue | 71,135 | 2.1% (2.0, 2,2) |

| Diseases of the Circulatory System | 111,931 | 5.7% (5.6, 5.8) |

| Injury and Poisoninga | 99,404 | 3.4% (3.3, 3.5) |

| Diseases of the Respiratory System | 16,672 | 11.0% (10.5, 11.5) |

| Infectious and Parasitic Diseases | 12,522 | 10.1% (9.6, 10.6) |

| Diseases of the Genitourinary System | 10,904 | 9.6% (9.0, 10.2) |

| Diseases of the Digestive System | 11,768 | 6.9% (6.4, 7.4) |

| Neoplasms | 10,139 | 5.9% (5.4, 6.4) |

| Endocrine, Nutritional, and Metabolic Diseases and Immunity Disorders | 6,777 | 6.9% (6.3, 7.5) |

| Diseases of Nervous System and Sense Organs | 10,965 | 4.5% (4.1, 4.9) |

| Diseases of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue | 2,288 | 10.7% (9.4, 12.0) |

| Disease of Blood and Blood-Forming Organs | 1,192 | 8.3% (6.7, 9.9) |

| Mental Disorders | 1,005 | 4.5% (3.2, 5.8) |

| Congenital Anomalies | 839 | 2.3% (1.3, 3.3) |

| Other | 4,305 | 5.5% (4.8, 6.2) |

| Hospital LOS | ||

| <4 days | 124,842 | 3.0% (2.9, 3.1) |

| 4 to 7 days | 158,784 | 4.8% (4.7, 4.9) |

| >7 days | 88,220 | 8.0% (7.8, 8.2) |

| ICU/CCU | ||

| No | 205,227 | 4.0% (3.9, 4.1) |

| Yes | 166,619 | 6.2% (6.1, 6.3) |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Sum | ||

| 0–1 | 40,901 | 1.6% (1.5, 1.7) |

| 2–4 | 197,610 | 3.6% (3.5, 3.7) |

| 5+ | 133,335 | 8.0% (7.9, 8.1) |

| IR Impairment group | ||

| LE Fracture | 57,478 | 3.2% (3.1, 3.3) |

| Stroke | 77,751 | 4.1% (4.0, 4.2) |

| LE Joint Replacement | 42,279 | 1.4% (1.3, 1.5) |

| Neurologic Disorders | 36,139 | 7.8% (7.5, 8.1) |

| Debility | 34,484 | 8.0% (7.7, 8.3) |

| Brain Injury | 28,674 | 5.4% (5.1, 5.7) |

| Other Ortho Conditions | 25,346 | 3.2% (3.0, 3.4) |

| Cardiac Conditions | 22,738 | 9.9% (9.5, 10.3) |

| Spinal Cord Injury | 15,507 | 3.6% (3.3, 3.9) |

| Other | 31,450 | 6.8% (6.5, 7.1) |

| IR Program Interruption | ||

| No | 369,884 | 5.0% (4.9, 5.1) |

| Yes | 1,962 | 6.8% (5.7, 7.9) |

| Bowel/Bladder Management | ||

| <9 | 97,257 | 7.1% (6.9, 7.3) |

| 9–12 | 184,978 | 4.5% (4.4, 4.6) |

| >12 | 89,611 | 3.5% (3.4, 3.6) |

| Self-care|| | ||

| <28 | 93,615 | 6.9% (6.7, 7.1) |

| 28–36 | 191,799 | 4.7% (4.6, 4.8) |

| >36 | 86,432 | 3.4% (3.3, 3.5) |

| Mobility|| | ||

| <18 | 87,656 | 7.2% (7.0, 7.4) |

| 18–26 | 189,021 | 4.8% (4.7, 4.9) |

| >26 | 95,169 | 3.3% (3.2, 3.4) |

| Cognition|| | ||

| <25 | 86,935 | 6.2% (6.0, 6.4) |

| 25–32 | 191,620 | 5.1% (5.0, 5.2) |

| >32 | 93,291 | 3.5% (3.4, 3.6) |

Abbreviations: CCS, Clinical Classification Software; LOS, length of stay; IR, inpatient rehabilitation; LE, lower extremity; Ortho, orthopedic

Race/ethnicity missing for 968 cases in the overall sample and 41 cases with potentially preventable post-discharge readmissions. “Other” includes the categories Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and Other.

“Disability” original reason for receiving Medicare.

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

(HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) 2015. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/CCSUsersGuide.pdf. Accessed 5/16/2016.

Functional score at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Domains generated from items in the Functional Independence Measure. Self-care: 6 items related to eating, grooming, bathing, dressing-upper body, dressing-lower body, and toileting (score range 6–42); Mobility: 5 items related to transfers, walking/wheelchair mobility, and ability to climb stairs (score range 5–35); Cognition: 5 items related to comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem solving, and memory (score range 5–35). Domain scores categorized as lowest quartile, interquartile range, and highest quartile.

30-Day Potentially Preventable Readmissions

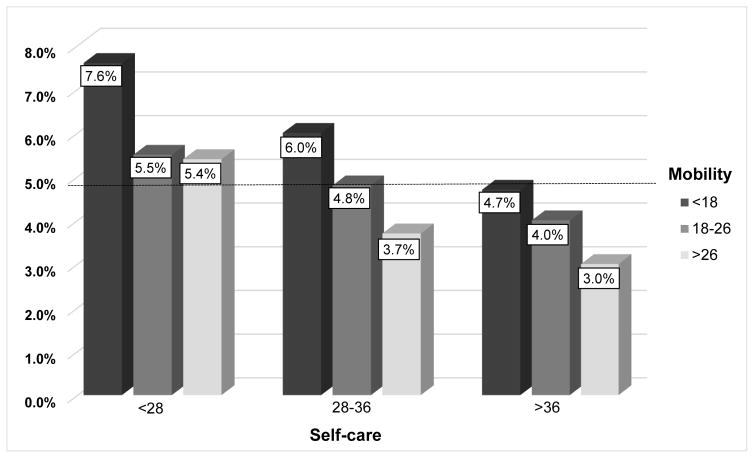

The overall rate of any 30-day hospital readmission following discharge from inpatient rehabilitation was 12.4% (N=46,265). When limited to potentially preventable hospital readmissions, the overall rate was 5.0% (N=18,477). Observed rates and adjusted odds of 30-day potentially preventable readmissions by patient characteristics are presented in Tables 1 to 3. Regarding the predictors of interest, observed rates (95% CI) for the highest vs. lowest quartiles within each functional domain were as follows: self-care: 3.4% (3.3–3.5) vs 6.9% (6.7–7.1); mobility: 3.3% (3.2–3.4) vs 7.2% (7.0–7.4); and cognition 3.5% (3.4–3.6) vs 6.2% (6.0–6.4). Similarly, adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) for the highest vs. lowest quartiles within each functional domain were as follows: self-care: 0.70 (0.67–0.74); mobility: 0.64 (0.61–0.68); and cognition: 0.84 (0.80–0.89). Adjusted odds were also significantly lower for the interquartile range vs. the lowest quartile across all three functional domains. Observed rates for combinations of self-care and mobility performances are presented in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Odds ratios from the adjusted multilevel logistic regression model estimating the association between discharge mobility scores and potentially preventable 30-day readmissions following inpatient rehabilitation

| Odds Ratio (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| <75 | Ref |

| 75–84 | 1.21 (1.17, 1.26) |

| >84 | 1.41 (1.35, 1.47) |

| Sex | |

| Female | Ref |

| Male | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) |

| Race/ethnicity† | |

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.94 (0.88, 0.99) |

| Hispanic | 0.89 (0.83, 0.96) |

| Other | 0.71 (0.64, 0.80) |

| Disability entitlement‡ | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.16 (1.11, 1.21) |

| Dual eligibility§ | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.18 (1.13, 1.23) |

| Prior hospitalizations | |

| 0 | Ref |

| 1 | 1.41 (1.36, 1.46) |

| 2 | 1.79 (1.70, 1.89) |

| 3+ | 2.51 (2.36, 2.66) |

| CCS Diagnostic category|| | |

| Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System and | Ref |

| Connective Tissue | |

| Diseases of the Circulatory System | 1.51 (1.39, 1.64) |

| Injury and Poisoning | 1.03 (0.95, 1.11) |

| Diseases of the Respiratory System | 2.15 (1.96, 2.34) |

| Infectious and Parasitic Diseases | 1.88 (1.71, 2.06) |

| Diseases of the Genitourinary System | 1.88 (1.70, 2.07) |

| Diseases of the Digestive System | 1.29 (1.16, 1.43) |

| Neoplasms | 1.36 (1.22, 1.52) |

| Endocrine, Nutritional, and Metabolic Diseases and Immunity Disorders | 1.35 (1.20, 1.53) |

| Diseases of Nervous System and Sense Organs | 1.10 (0.98, 1.24) |

| Diseases of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue | 2.19 (1.88, 2.56) |

| Disease of Blood and Blood-Forming Organs | 1.52 (1.22, 1.89) |

| Mental Disorders | 0.99 (0.73, 1.35) |

| Congenital Anomalies | 0.90 (0.57, 1.43) |

| Other | 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) |

| Hospital LOS | |

| <4 days | Ref |

| 4 to 7 days | 1.13 (1.08, 1.18) |

| >7 days | 1.36 (1.30, 1.43) |

| ICU/CCU | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Sum | |

| 0–1 | Ref |

| 2–4 | 1.65 (1.52, 1,79) |

| 5+ | 2.57 (2.36, 2.79) |

| IR Impairment group | |

| LE Fracture | Ref |

| Stroke | 0.80 (0.73, 0.87) |

| LE Joint Replacement | 0.75 (0.67, 0.84) |

| Neurologic Disorders | 1.39 (1.29, 1.51) |

| Debility | 1.32 (1.22, 1.43) |

| Brain Injury | 1.12 (1.03, 1.21) |

| Other Ortho Conditions | 1.10 (1.01, 1.20) |

| Cardiac Conditions | 1.66 (1.52, 1.81) |

| Spinal Cord Injury | 1.15 (1.03, 1.29) |

| Other | 1.24 (1.15, 1.34) |

| IR Program Interruption | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.24 (1.04, 1.49) |

| Bowel/Bladder Management | |

| <9 | Ref |

| 9–12 | 0.80 (0.77, 0.83) |

| >12 | 0.73 (0.69, 0.76) |

| Mobility¶ | |

| <18 | Ref |

| 18–26 | 0.79 (0.76, 0.82) |

| >26 | 0.64 (0.61, 0.68) |

| Cognition¶ | |

| <25 | Ref |

| 25–32 | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) |

| >32 | 0.84 (0.80, 0.89) |

Abbreviations: CCS, Clinical Classification Software; LOS, length of stay; IR, inpatient rehabilitation; LE, lower extremity; Ortho, orthopedic

ORs from a multilevel model adjusted for all patient-level characteristics in the table.

Race/ethnicity missing for 968 cases in the overall sample and 41 cases with potentially preventable post-discharge readmissions. “Other” includes the categories Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and Other.

“Disability” original reason for receiving Medicare.

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) 2015. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/CCSUsersGuide.pdf. Accessed 5/16/2016.

Functional score at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Domains generated from items in the Functional Independence Measure. Mobility: 5 items related to transfers, walking/wheelchair mobility, and ability to climb stairs (score range 5–35); Cognition: 5 items related to comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem solving, and memory (score range 5–35). Domain scores categorized as lowest quartile, interquartile range, and highest quartile.

Figure 2.

Observed rates of 30-day potentially preventable readmissions for all combinations of levels of performance across the self-care and mobility domains at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Domains generated from items in the Functional Independence Measure. Self-care: 6 items related to eating, grooming, bathing, dressing-upper body, dressing-lower body, and toileting (score range 6–42); Mobility: 5 items related to transfers, walking/wheelchair mobility, and ability to climb stairs (score range 5–35). Domain scores categorized as lowest quartile, interquartile range, and highest quartile. Number of discharges within each category (from left to right on figure): Self-care <28, Mobility <18, n=64,550; Self-care <28, Mobility 18–26, n=28,474; Self-care <28, Mobility >26, n=591; Self-care 28–36, Mobility <18, n=22,255; Self-care 28–36, Mobility 18–26, n=128,988; Self-care 28–36, Mobility >26, n=40,556; Self-care >36, Mobility <18, n=851; Self-care >36, Mobility 18–26, n=31,559; Self-care >36, Mobility >26, n=54,022.

Older age, male sex, disability entitlement, dual eligibility, more prior hospitalizations, longer index hospitalizations, more comorbidities, and experiencing a program interruption during inpatient rehabilitation were all associated with 30-day potentially preventable readmissions in adjusted analyses (Tables 2 and 3). Non-Hispanic black and Hispanic patients had lower adjusted odds, as did patients with greater independence in bowel and bladder management. Rates and odds of 30-day potentially preventable readmissions varied widely across index hospitalization diagnostic categories and inpatient rehabilitation impairment groups.

Table 2.

Odds ratios from the adjusted multilevel logistic regression model estimating the association between discharge self-care scores and potentially preventable 30-day readmissions following inpatient rehabilitation

| Odds Ratio (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| <75 | Ref |

| 75–84 | 1.21 (1.16, 1.26) |

| >84 | 1.40 (1.34, 1.46) |

| Sex | |

| Female | Ref |

| Male | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) |

| Race/ethnicity† | |

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.93 (0.88, 0.99) |

| Hispanic | 0.89 (0.82, 0.96) |

| Other | 0.71 (0.63, 0.79) |

| Disability entitlement‡ | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.16 (1.11, 1.22) |

| Dual eligibility§ | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24) |

| Prior hospitalizations | |

| 0 | Ref |

| 1 | 1.42 (1.37, 1.47) |

| 2 | 1.80 (1.71, 1.90) |

| 3+ | 2.53 (2.38, 2.69) |

| CCS Diagnostic category|| | |

| Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue | Ref |

| Diseases of the Circulatory System | 1.52 (1.40, 1.65) |

| Injury and Poisoning | 1.03 (0.96, 1.12) |

| Diseases of the Respiratory System | 2.15 (1.97, 2.35) |

| Infectious and Parasitic Diseases | 1.89 (1.72, 2.08) |

| Diseases of the Genitourinary System | 1.89 (1.71, 2.08) |

| Diseases of the Digestive System | 1.29 (1.16, 1.43) |

| Neoplasms | 1.37 (1.22, 1.53) |

| Endocrine, Nutritional, and Metabolic Diseases and Immunity Disorders | 1.38 (1.22, 1.55) |

| Diseases of Nervous System and Sense Organs | 1.11 (0.99, 1.24) |

| Diseases of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue | 2.23 (1.91, 2.60) |

| Disease of Blood and Blood-Forming Organs | 1.52 (1.22, 1.89) |

| Mental Disorders | 0.98 (0.72, 1.34) |

| Congenital Anomalies | 0.90 (0.57, 1.43) |

| Other | 1.10 (0.95, 1.28) |

| Hospital LOS | |

| <4 days | Ref |

| 4 to 7 days | 1.13 (1.09, 1.18) |

| >7 days | 1.37 (1.31, 1.44) |

| ICU/CCU | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Sum | |

| 0–1 | Ref |

| 2–4 | 1.65 (1.52, 1.80) |

| 5+ | 2.59 (2.38, 2.82) |

| IR Impairment group | |

| LE Fracture | Ref |

| Stroke | 0.76 (0.70, 0.83) |

| LE Joint Replacement | 0.74 (0.66, 0.83) |

| Neurologic Disorders | 1.35 (1.25, 1.46) |

| Debility | 1.28 (1.18, 1.38) |

| Brain Injury | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) |

| Other Ortho Conditions | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) |

| Cardiac Conditions | 1.60 (1.47, 1.75) |

| Spinal Cord Injury | 1.13 (1.01, 1.26) |

| Other | 1.22 (1.13, 1.32) |

| IR Program Interruption | |

| No | Ref |

| Yes | 1.25 (1.04, 1.50) |

| Bowel/Bladder Management | |

| <9 | Ref |

| 9–12 | 0.79 (0.76, 0.82) |

| >12 | 0.71 (0.67, 0.74) |

| Self-care¶ | |

| <28 | Ref |

| 28–36 | 0.81 (0.78, 0.85) |

| >36 | 0.70 (0.67, 0.74) |

| Cognition¶ | |

| <25 | Ref |

| 25–32 | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) |

| >32 | 0.84 (0.80, 0.89) |

Abbreviations: CCS, Clinical Classification Software; LOS, length of stay; IR, inpatient rehabilitation; LE, lower extremity; Ortho, orthopedic

ORs from a multilevel model adjusted for all patient-level characteristics in the table.

Race/ethnicity missing for 968 cases in the overall sample and 41 cases with potentially preventable post-discharge readmissions. “Other” includes the categories Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and Other.

“Disability” original reason for receiving Medicare.

Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) 2015. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/CCSUsersGuide.pdf. Accessed 5/16/2016.

Functional score at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Domains generated from items in the Functional Independence Measure. Self-care: 6 items related to eating, grooming, bathing, dressing-upper body, dressing-lower body, and toileting (score range 6–42); Cognition: 5 items related to comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem solving, and memory (score range 5–35). Domain scores categorized as lowest quartile, interquartile range, and highest quartile.

Of the 18,477 potentially preventable readmissions identified, 44.1% were for conditions related to inadequate management of infection, 31.2% for conditions related to inadequate management of chronic conditions, and 24.7% for conditions related to inadequate management of other unplanned events. The five most common diagnoses within each category are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Five most common reasons for potentially preventable 30-day readmissions following inpatient rehabilitation by category

| Inadequate Management of Infection (n=8,148, 44.1%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| ICD-9 | Diagnosis | %* |

| 038.9 | Unspecified septicemia | 27.6 |

| 599.0 | Urinary tract infection site not specified | 21.6 |

| 486 | Pneumonia organism unspecified | 18.3 |

| 008.45 | Intestinal infection due to clostridium difficile | 8.8 |

| 682.6 | Cellulitis and abscess of leg, except foot | 6.3 |

| Inadequate Management of Chronic Conditions (n=5,773, 31.2%) | ||

| ICD-9 | Diagnosis | %* |

| 428.33 | Acute on chronic diastolic heart failure | 19.2 |

| 428.23 | Acute on chronic systolic heart failure | 16.7 |

| 491.21 | Obstructive Chronic Bronchitis with acute exacerbation | 13.4 |

| 428.0 | Congestive heart failure | 9.4 |

| 428.43 | Acute on chronic combined systolic and diastolic heart failure | 6.2 |

| Inadequate Management of Other Unplanned Events (n=4,556, 24.7%) | ||

| ICD-9 | Diagnosis | %* |

| 584.9 | Acute kidney failure, unspecified | 34.7 |

| 427.31 | Atrial Fibrillation | 22.0 |

| 507.0 | Pneumonitis due to inhalation of food or vomitus | 13.8 |

| 276.51 | Dehydration | 7.7 |

| 276.1 | Hyposmolality and/or hyponatremia | 6.2 |

Percentage of readmissions within the category for the specified ICD-9 code.

Discussion

In this national cohort of aged Medicare beneficiaries, patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation was associated with their risk of a potentially preventable readmission over the following 30 days. Compared to patients in the lowest quartiles, those in the top quartiles for mobility, self-care, and cognition had 36% lower, 30% lower, and 16% lower odds of readmission, respectively. Our findings extend previous work demonstrating the association between functional status following inpatient rehabilitation and hospital readmissions.8,15–17 The focus is shifting to identifying readmissions that may be avoidable, and therefore, represent amenable targets for care-improvement initiatives. Our findings indicate functional status may be a risk factor for potentially preventable hospital readmissions after inpatient rehabilitation.

Functional recovery during inpatient rehabilitation is a patient-centered outcome. Accordingly, improving patients’ functional independence is the primary goal of care in this setting.7 This is recognized at the policy-level, and providers are becoming increasingly accountable for patients’ functional outcomes. The IMPACT Act mandates the development of standardized functional measures for postacute settings.1 These measures will be used to assess quality of care.1 Functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation is associated with a resource use metric mandated by the IMPACT Act: 30-day potentially preventable readmissions.1 Therefore, maximizing patients’ functional outcomes during inpatient rehabilitation may lead to higher value care by improving provider performance on both quality and resource use metrics. Continuing to improve the value of inpatient rehabilitation will be critical as payment reforms, such as episode-based payments, are implemented.

Episode-based payment models extend episodes of care across providers and settings.18 Through these and other quality initiatives, providers are financially incentivized to deliver efficient, coordinated healthcare. Improving care transitions and post-discharge outcomes are priority areas.18,19 To be efficient, efforts should target at-risk individuals and focus on the common conditions resulting in adverse events, such as rehospitalizations.

A secondary objective of our study was to examine the primary conditions underlying potentially preventable readmissions over the 30 days following inpatient rehabilitation. In our cohort, 44% of the potentially preventable readmissions were for conditions related to infection; the top three were septicemia, urinary tract infection, and pneumonia. Heart failure and kidney failure were other common conditions resulting in readmissions. The common conditions point to some potential mechanisms underlying the association between functional status and potentially preventable readmissions. Perhaps older adults with greater independence in self-care, mobility, and cognition are able to maintain good personal hygiene, which could lower risk of infections. They may also be more capable of managing chronic conditions and preventing exacerbations. Patients discharged with risk factors for a potentially preventable readmission, such as functional dependence, may benefit from patient/caregiver education during care transitions. The interdisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation team can proactively prepare the patient and caregivers for preventing infections and managing chronic conditions post-discharge.

Our findings highlight that there may be opportunities for further reducing overall readmission rates after postacute care; 40% of all the readmissions we observed in our national cohort were for “potentially preventable” conditions. Reducing rates of readmissions aligns with the triple aim of healthcare reform to improve patient experiences, improve the health of populations, and reduce healthcare costs.20 The association between patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and 30-day potentially preventable readmissions has three important implications from a care-improvement perspective. First, these findings re-emphasize the importance of maximizing patients’ functional recovery during inpatient rehabilitation. Secondly, these findings provide insight into which patients may be at increased risk for potentially preventable readmissions. Finally, because functional status is a risk factor, these findings can inform development of prevention programs.

Study Limitations

We used administrative and assessment data to address our study objectives. This provided a national sample of aged Medicare beneficiaries. However, there are limitations to using these files to address research questions, including a lack of information regarding the accuracy of data entry.21 These data files also do not include robust sociodemographic information. There are likely sociodemographic characteristics, such as availability of caregivers, which influence readmission rates. Access to inpatient rehabilitation facilities and hospitals and other market factors may also influence potentially preventable readmission rates. These factors are not accounted for in the current study.

We used the list of diagnoses developed for the 30-day potentially preventable readmission measure to identify our outcome. The diagnoses on the list may have varying degrees of preventability, and some readmissions for these conditions may be unavoidable. However, we followed the list specified for the measure because these are the diagnoses that will used for quality reporting. Although we used the readmission diagnoses from the measure, we did not replicate the cohort selection criteria. Our cohort is older (79.1 vs 75.3 years)7 and likely healthier than the overall Medicare fee-for-service inpatient rehabilitation population, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Our findings are generalizable to the Medicare fee-for-service population over the age of 65 years who survive for 32 days post-rehabilitation discharge. Findings may differ for younger individuals, sicker individuals, and those with a different payer (e.g. Medicare Managed Care, private insurance).

Our analyses are observational, and results should be interpreted as such. We observed an association between patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and 30-day potentially preventable readmissions. This association remained after adjusting for patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and held across the functional domains of self-care, mobility, and cognition. Our findings provide insight into identifying patients who are at-risk, but not whether improving patients’ functional independence will reduce rates. This is something we hypothesize based on our findings.

Conclusions

Patients’ functional status at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation is associated with 30-day potentially preventable readmissions. Including information on patients’ functional status may be important during care transitions, and patients with limitations in self-care, mobility, or cognitive activities may benefit from customized follow-up programs. Our findings provide insight into identifying patients who are at-risk; however, prospective research is needed to determine whether follow-up programs focused on functional independence reduce readmission rates.

Acknowledgments

This work has not been previously presented. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01 HD069443, P30-AG024832, and 5K12HD055929-09); the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (grant number 90AR5009), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R24 HS022134). The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- FIM

Functional Independence Measure

- ICU/CCU

intensive care or coronary care unit utilization

- IMPACT Act

Improving Medicare Post-acute Care Transformation Act

- IRF-PAI

Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument

- MedPAR

Medicare Provider Analysis and Review

Footnotes

IBM® SPSS 23, IBM Corporation, 1 New Orchard Road, Armonk, NY 10504-1722.

SAS version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., 100 SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC 27513-2414.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1. [Accessed 9/1/2016];Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014, PL 113–185. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/113/hr4994.

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Register. Medicare Program; Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Prospective Payment System for Federal Fiscal Year 2017. [Accessed 11/18/2016];Final Rule. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-08-05/pdf/2016-18196.pdf. [PubMed]

- 3.RTI International. [Accessed 4/12/2017];Measure Specifications for Measures Adopted in the FY 2017 IRF QRP Final Rule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/IRF-Quality-Reporting/Downloads/Measure-Specifications-for-FY17-IRF-QRP-Final-Rule.pdf.

- 4.Das A, Norton EC, Miller DC, Chen LM. Association of Postdischarge Spending and Performance on New Episode-Based Spending Measure. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(1):117–119. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai TC, Greaves F, Zheng J, Orav EJ, Zinner MJ, Jha AK. Better Patient Care At High-Quality Hospitals May Save Medicare Money And Bolster Episode-Based Payment Models. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(9):1681–1689. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. [Accessed 7/20/2016];Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Available at: http://medpac.gov/documents/reports/june-2016-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

- 7.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. [Accessed 4/11/2017];Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2017 Mar; Available at: http://medpac.gov/-documents-/reports.

- 8.Middleton A, Graham JE, Lin YL, et al. Motor and Cognitive Functional Status Are Associated with 30-day Unplanned Rehospitalization Following Post-Acute Care in Medicare Fee-for-Service Beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3704-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed 6/16/2016];The Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility-Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) Training Manual. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/InpatientRehabFacPPS/IRFPAI.html.

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed 05/17/2016];Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) File. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/IdentifiableDataFiles/MedicareProviderAnalysisandReviewFile.html.

- 11.ResDAC. [Accessed 5/17/2016];Master Beneficiary Summary File. Available at: https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/files/mbsf.

- 12.Stineman MG, Ross RN, Fiedler R, Granger CV, Maislin G. Functional independence staging: conceptual foundation, face validity, and empirical derivation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(1):29–37. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) [Accessed 5/16/2016];2015 Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/CCSUsersGuide.pdf.

- 14.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher SR, Graham JE, Krishnan S, Ottenbacher KJ. Predictors of 30-Day Readmission Following Inpatient Rehabilitation for Patients at High Risk for Hospital Readmission. Phys Ther. 2016;96(1):62–70. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20150034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ottenbacher KJ, Karmarkar A, Graham JE, et al. Thirty-day hospital readmission following discharge from postacute rehabilitation in fee-for-service Medicare patients. JAMA. 2014;311(6):604–614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galloway RV, Karmarkar AM, Graham JE, et al. Hospital Readmission Following Discharge From Inpatient Rehabilitation for Older Adults With Debility. Phys Ther. 2016;96(2):241–251. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20150030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals--HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):897–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed 2/3/2017];List of Measures under Consideration for December 1, 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/Downloads/Measures-under-Consideration-List-for-2016.pdf.

- 20.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(3):759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Walraven C, Austin P. Administrative database research has unique characteristics that can risk biased results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(2):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]