Abstract

3-Deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo) is an essential component of LPS in the outer leaflet of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. Although labeling of Escherichia coli with the chemical reporter 8-azido-3,8-dideoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo-N3) has been reported, its incorporation into LPS has not been directly shown. We have now verified Kdo-N3 incorporation into E. coli LPS at the molecular level. Using microscopy and PAGE analysis, we show that Kdo-N3 is localized to the outer membrane and specifically incorporates into rough and deep-rough LPS. In an E. coli strain lacking endogenous Kdo biosynthesis, supplementation with exogenous Kdo restored full-length core-LPS, which suggests that the Kdo biosynthetic pathways might not be essential in vivo in the presence of sufficient exogenous Kdo. In contrast, exogenous Kdo-N3 only restored a small fraction of core LPS with the majority incorporated into truncated LPS. The truncated LPS were identified as Kdo-N3–lipid IVA and (Kdo-N3)2–lipid IVA by MS analysis. The low level of Kdo-N3 incorporation could be partly explained by a 6-fold reduction in the specificity constant of the CMP-Kdo synthetase KdsB with Kdo-N3 compared with Kdo. These results indicate that the azido moiety in Kdo-N3 interferes with its utilization and may limit its utility as a tracer of LPS biosynthesis and transport in E. coli. We propose that our findings will be helpful for researchers using Kdo and its chemical derivatives for investigating LPS biosynthesis, transport, and assembly in Gram-negative bacteria.

Keywords: gel electrophoresis, gram-negative bacteria, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), mass spectrometry (MS), metabolic tracer, microscopy, outer membrane, Kdo, labeling

Introduction

The treatment of Gram-negative bacterial infections has become a growing challenge due to increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance (1–4). The discovery of new antibiotics for these organisms is particularly demanding because of the Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane (OM),3 which serves as a permeability barrier and hinders compounds from entering the cell (5). A key characteristic of the OM is its asymmetry, with an inner leaflet of phospholipids and an outer leaflet of lipopolysaccharides (LPS or endotoxin) (6). LPS consists of three parts: lipid A (embedded in the outer leaflet of the OM), the core-oligosaccharide, and the O-antigen. In nearly all Gram-negative bacteria, the first core sugar attached to lipid A is 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo) (7). Kdo2-lipid A, or deep-rough LPS, is the minimal LPS needed for growth in a variety of Gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli (8), and triggers the human innate immune response (7, 9). Rough LPS consists of core sugars attached to lipid A but lacks the O-antigen found in smooth LPS. A profound understanding of LPS biosynthesis, transport, and assembly in vivo and in vitro may be crucial for developing new classes of antibiotics (10).

In the last decade, there have been great advances in metabolic engineering and bioorthogonal “click” chemistry to label biomolecules in mammalian cells and, more recently, in bacteria (11–13). The incorporation of functionalized substrates like an amino acid or monosaccharide into mammalian cells or bacteria, followed by labeling via click chemistry, allows the direct investigation of the native biological environment with the unnatural analog (14, 15). In this context, Dumont et al. (16) showed that Gram-negative bacteria can be labeled by treatment with an exogenous Kdo analog, 8-azido-3,8-dideoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo-N3), followed by a copper-catalyzed click reaction with a fluorescent reagent. In addition, Fugier et al. utilized copper-free click chemistry to label Kdo-N3–treated E. coli cells with a biotin derivative (17). The biotin-labeled bacteria were captured by magnetic streptavidin beads. This method allowed the enrichment and detection of E. coli in biological samples in the presence of other microbes. More recently, Wang et al. (18) applied Kdo-N3 labeling in vivo to selectively image Gram-negative bacteria in the gut microbiota of mice.

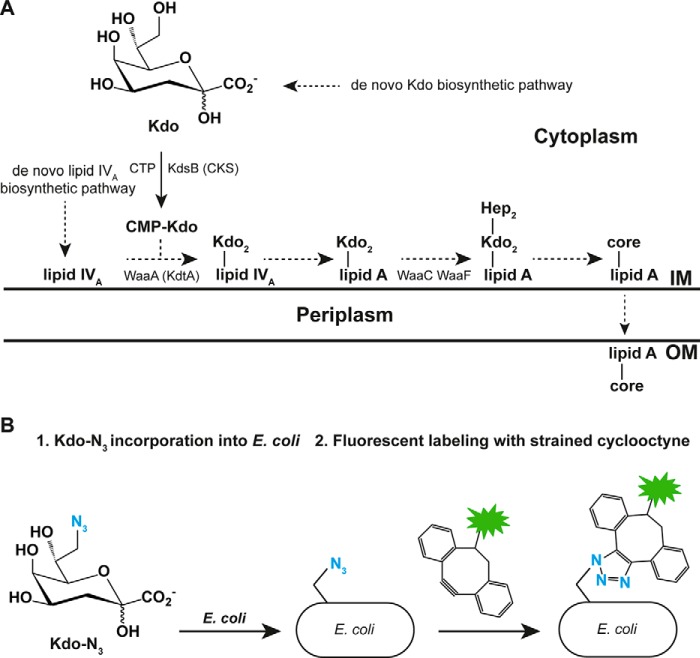

Although the uptake mechanism is not known, exogenously supplied Kdo-N3 is presumed to be incorporated into the LPS via the same pathway as endogenous Kdo (Fig. 1A) (16, 19, 20). If LPS containing Kdo-N3 were flipped from the cytoplasm to the periplasm and further transported to the outer leaflet of the OM (21), Kdo-N3 in the LPS would then be available for labeling with suitable partners (Fig. 1B). However, Kdo-N3 incorporation into LPS has not yet been proven on a molecular level, which is important to understand the advantages and drawbacks of Kdo-N3 labeling and to utilize this method to study LPS biology. Here, we report the molecular characterization of Kdo-N3 incorporation into E. coli LPS and reveal limitations of this method.

Figure 1.

Incorporation of Kdo-N3 into the LPS of Gram-negative bacteria. A, scheme for known core-lipid A biosynthesis in E. coli K-12 (8, 46). Dashed arrows, multiple steps. KdsB (CKS), 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonate cytidylyltransferase; WaaA (KdtA), Kdo transferase; WaaC, ADP-heptose:LPS heptosyltransferase I; WaaF, ADP-heptose:LPS heptosyltransferase II; Hep, heptose; IM, inner membrane; OM, outer membrane. B, scheme for Kdo-N3 metabolic labeling: incubation of E. coli K-12 with Kdo-N3 and copper-free click labeling with a fluorescent strained alkyne. The labeled cells can be analyzed by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry.

Results

Fluorescent labeling of E. coli cells with Kdo-N3 and a fluorescent copper-free click reagent

Fugier et al. (17) previously reported a method to fluorescently label E. coli: bacteria were grown in the presence of Kdo-N3 followed by sequential incubation with a strained cyclooctyne containing biotin and an anti-biotin Alexa Fluor 488 antibody. We grew E. coli K-12 for 16 h with and without supplementation of 1 mm Kdo-N3 (synthesized as described under “Experimental procedures”) followed by specific labeling of the N3 moiety with Click-IT Alexa Fluor 488-DIBO alkyne (Alexa488-DIBO). This commercially available strained cyclooctyne, which reacts selectively with azides via copper-free click reaction, contains the green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 moiety, allowing fluorescent click labeling with a single step (22–24) (supplemental Fig. S1A). Cells grown in the presence of Kdo-N3 and treated with Alexa488-DIBO were fluorescent (supplemental Fig. S2B), whereas no fluorescent labeling with Alexa488-DIBO was observed for cells grown without Kdo-N3 and treated with Alexa488-DIBO (supplemental Fig. S2A). The dose- and time-dependent studies for Kdo-N3 labeling by flow cytometry showed that cells grown in the presence of ≥0.1 mm Kdo-N3 were readily labeled (supplemental Fig. S3A) and that 4-h or longer incubation with Kdo-N3 was required for substantial labeling of E. coli (supplemental Fig. S3C).

Localization of fluorescent click-labeled Kdo-N3 to the outer membrane

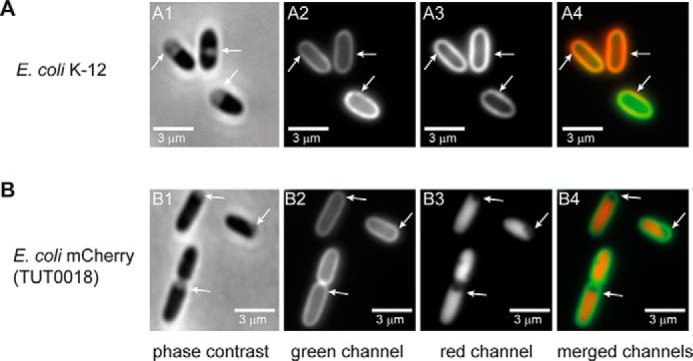

The green fluorescence observed after labeling E. coli should be localized to the OM if Kdo-N3 is incorporated into the LPS. Although LPS is biosynthesized in the inner membrane (IM), it is then transported directly to the outer leaflet of the OM (21), where any Kdo-N3–containing LPS would be available to react with Alexa488-DIBO. To confirm the OM localization of the reacted Alexa488-DIBO, the click-labeled cells were imaged after osmotic shock treatment with high sucrose solution (plasmolysis). During plasmolysis, the cytoplasm shrank, whereas the OM retained its shape, leading to an increased separation of the IM and OM (Fig. 2, A1 and B1, marked with arrows). The expanded periplasm facilitated the differential localization of fluorophores to the cytoplasm, IM, periplasm, and OM (25). In Alexa488-DIBO–labeled E. coli cells stained with the membrane dye FM 4-64, the green fluorescent Alexa Fluor 488 (Fig. 2A2) and the red fluorescent FM 4-64 (Fig. 2, A3 and A4) were co-localized to the OM. This is consistent with a previous report that FM 4-64 preferentially stains the OM and not the IM of intact wild-type E. coli (26). To delineate the IM, we imaged plasmolyzed Alexa488-DIBO–labeled E. coli K-12 expressing mCherry, a red fluorescent protein, in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2B3). We found that the green Alexa488-DIBO was also localized to the OM in these cells, whereas the red fluorescence was localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2B4), confirming the localization of Kdo-N3 to the OM.

Figure 2.

Localization of the click-labeled Kdo-N3 in the OM by plasmolysis. A and B, E. coli K-12 (A1–A4) and E. coli expressing cytoplasmic mCherry (TUT0018) (B1–B4) were grown with 1 mm Kdo-N3 and labeled with Alexa488-DIBO. E. coli K-12 was also stained with FM 4-64 membrane dye. The cells were then plasmolyzed and immediately visualized on a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope using phase contrast (A1 and B1) and fluorescence optics (A2, A3, B2, and B3). The Alexa 488 signal (A2 and B2) localized to the periphery of cells. The membrane of wild-type cells stained with FM 4-64 (A3) co-localized with the Alexa 488 (A4; overlay of A2 and A3). The cytoplasmic mCherry (B3) in TUT0018 was used as an indicator for plasmolysis. In the plasmolyzed regions (white arrows), the Alexa 488 did not localize to the IM (B4; overlay of B2 and B3). Images are representative of three independent experiments. Bar, 3 μm.

Confirmation of Kdo-N3 incorporation into E. coli LPS by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

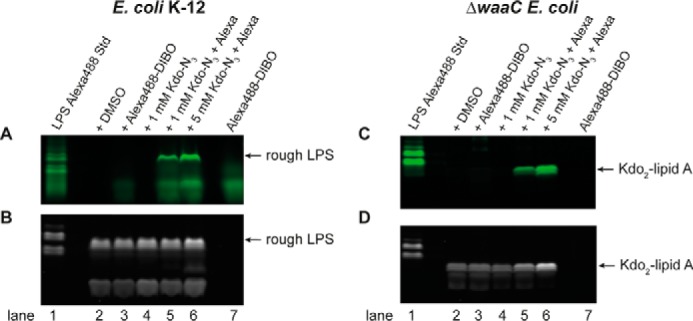

After localizing the fluorophore to the OM, Kdo-N3 incorporation into the LPS was validated on a molecular level using SDS-PAGE. E. coli cells were grown in the presence or absence of Kdo-N3, followed by reaction with Alexa488-DIBO and LPS separation by SDS-PAGE. The fluorescent gel image showed a green fluorescent band in the sample from cells grown with Kdo-N3 and treated with Alexa488-DIBO (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 and 6). This band was not detected in the control samples: untreated cells (lane 2), cells grown without Kdo-N3 and treated with Alexa488-DIBO (lane 3), and cells grown with Kdo-N3 but untreated with Alexa488-DIBO (lane 4). As an additional control, the Alexa488-DIBO reagent alone ran faster than the Alexa488-DIBO fluorescently labeled LPS bands (lanes 5 and 6) in a broad, diffuse band (lane 7). The SDS-polyacrylamide gel was then developed with the Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS gel stain kit to visualize all LPS bands containing sugars (27). All E. coli samples (lanes 2–6) showed a very similar Pro-Q Emerald 300 fluorescent LPS pattern (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Incorporation of Kdo-N3 into LPS of E. coli K-12 and ΔwaaC E. coli. E. coli K-12 and ΔwaaC E. coli were grown in LB with and without 1 mm or 5 mm Kdo-N3, respectively, and fluorescently labeled with Alexa488-DIBO. The LPS were separated by SDS-PAGE. A and C, images of SDS-polyacrylamide gels of E. coli K-12 (A) and ΔwaaC E. coli (C) visualized by fluorescent imaging for Alexa Fluor 488. B and D, images of SDS-polyacrylamide gels of E. coli K-12 (B) and ΔwaaC E. coli (D) after staining LPS with the Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS staining kit. The data are representative of three independent biological replicates.

To better enable comparison of the Alexa Fluor 488 (Fig. 3A) and the Pro-Q Emerald 300 UV-fluorescence images (Fig. 3B), LPS from E. coli serotype O55:B5 Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (the only commercially available fluorescent LPS probe) was run as a control (lane 1). This conjugate showed fluorescence because of its Alexa Fluor 488 label and was subsequently visible upon Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS staining due to its LPS sugars. By comparison with this control (lane 1), the Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescent band of E. coli K-12 (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 and 6) migrated at the same position as the rough LPS band (Fig. 3B, lanes 2–6) visualized with the Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS kit. It is important to note that the Alexa Fluor 488 signal bled through under the UV light used to image total LPS. The same gel was also treated with Coomassie Blue stain and imaged to visualize the protein and ensure that the samples were equally loaded (see supplemental Fig. S4C).

Confirmation of Kdo-N3 incorporation into the LPS of a deep-rough E. coli mutant

To further confirm Kdo-N3 incorporation into LPS, Kdo-N3 labeling was studied in ΔwaaC E. coli, which lacks the core heptosyltransferase WaaC (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S7). WaaC adds the first heptose unit onto Kdo2-lipid A and therefore forms the attachment point for subsequent core sugars (28, 29) (supplemental Fig. S7B). ΔwaaC E. coli produces only Kdo2-lipid A (deep-rough LPS), which is smaller and has a faster electrophoretic mobility compared with rough LPS from E. coli K-12 (30). ΔwaaC E. coli was treated with or without Kdo-N3 and Alexa488-DIBO as described for E. coli K-12.

The LPS species from ΔwaaC E. coli were separated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3C) and imaged for green fluorescence. The Alexa488-DIBO reagent alone showed a similar SDS-PAGE migration pattern to fluorescently labeled Kdo2-lipid A. Therefore, the protocol was adapted to remove excess Alexa488-DIBO reagent by washing the gel overnight (with the standard washing solution described for the Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS staining kit) (Fig. 3C, lane 7). After the overnight wash, the gel image revealed a fluorescently labeled band only for ΔwaaC E. coli grown with Kdo-N3 and reacted with the Alexa488-DIBO (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 and 6). As observed for E. coli K-12, the control samples for ΔwaaC E. coli cultures did not show any fluorescent LPS bands (Fig. 3C, lanes 2–4). Upon LPS staining with the Pro-Q Emerald 300 kit (Fig. 3D), the gel showed a very similar LPS pattern for all samples (Fig. 3D, lanes 2–6). The faster migration of the fluorescent band (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 and 6) compared with the control LPS from E. coli serotype O55:B5 Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (Fig. 3C, lane 1) suggested that the band was the expected deep-rough LPS.

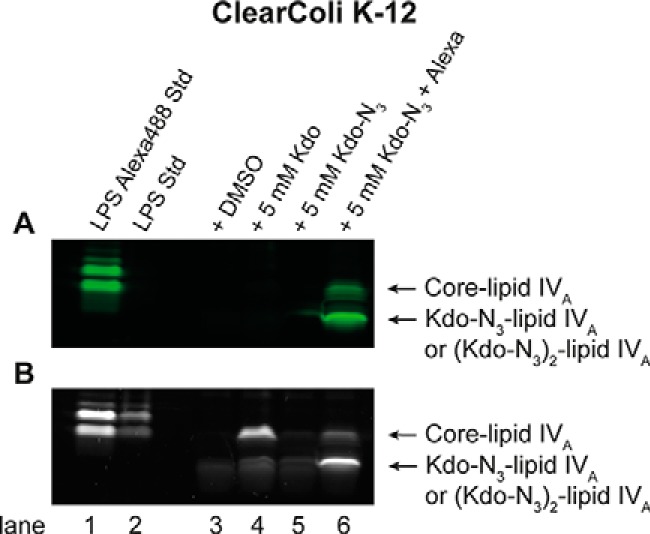

Restoration of LPS biosynthesis in ClearColi K-12 with exogenous Kdo and Kdo-N3

E. coli K-12 and ΔwaaC E. coli both have endogenous Kdo biosynthesis. Thus, exogenous Kdo-N3 is competing against endogenous Kdo, which makes it difficult to determine the level of Kdo-N3 incorporation into the LPS. To have a direct read-out of Kdo-N3 incorporation without the competition of endogenous Kdo, a commercially available E. coli K-12 strain (ClearColi K-12) was obtained that lacks endogenous Kdo synthesis but retains intact Kdo cytidylyltransferase (CMP-Kdo synthetase, KdsB, or CKS) and Kdo transferase (KdtA or WaaA) activities (see supplemental Fig. S7) (31, 32). ClearColi K-12 has been previously shown to synthesize only lipid IVA as its LPS (31). We hypothesized that this strain should be capable of synthesizing core-lipid IVA after uptake of exogenous Kdo or exogenous Kdo-N3. To test this hypothesis, ClearColi K-12 was grown in the presence or absence of 5 mm Kdo or 5 mm Kdo-N3 for 16 h followed by the reaction with Alexa488-DIBO.

After SDS-PAGE and Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS staining, a band equivalent to rough LPS (core-lipid IVA) was clearly visible from ClearColi K-12 grown with Kdo (Fig. 4B, lane 4). The uptake and substantial incorporation of exogenous Kdo into LPS has not been reported previously. Only a very faint LPS band was visible for ClearColi K-12 grown with Kdo-N3 (Fig. 4B, lane 5). The faster-migrating LPS bands in lanes 3–5 are most likely lipid IVA and one of its precursors, such as disaccharide 4′-monophosphate (see supplemental Fig. S7B) and did not appear to differ with Kdo or Kdo-N3 supplementation.

Figure 4.

Incorporation of Kdo and Kdo-N3 into LPS of ClearColi. ClearColi K-12 was grown in LB in the presence or absence of 5 mm Kdo or Kdo-N3 and labeled with Alexa488-DIBO. The whole-cell extracts were separated using SDS-PAGE. A, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled LPS in SDS-polyacrylamide gel visualized by fluorescent imaging; B, SDS-polyacrylamide gel after staining LPS with the Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS staining kit. The data are representative of three independent biological replicates.

Upon imaging the SDS-polyacrylamide gel for fluorescence (Fig. 4B), the ClearColi sample grown with Kdo-N3 and treated with Alexa488-DIBO revealed two green fluorescent bands (Fig. 4B, lane 6). The upper band corresponds to core-lipid IVA, whereas the lower band is consistent with a smaller, faster-migrating species missing some or all of the core sugars. It is important to note that the Alexa Fluor 488 label bled through under the UV light used to image total LPS, as lanes 5 and 6 only differ in the treatment with Alexa488-DIBO.

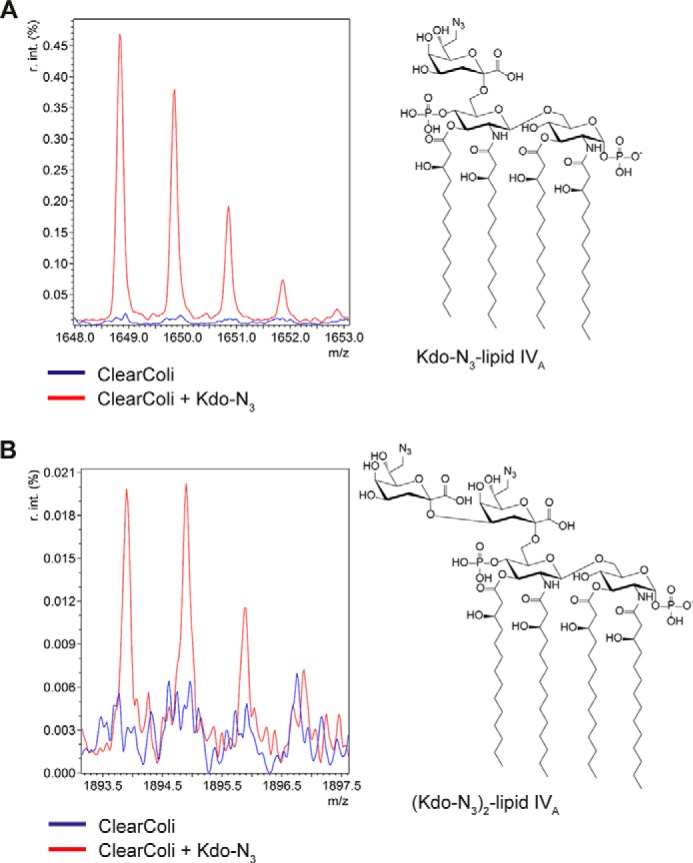

Mass spectrometry confirmation of Kdo-N3 addition to lipid IVA

The SDS-PAGE results indicated Kdo-N3 incorporation into the LPS of different E. coli strains. To directly confirm Kdo-N3 incorporation, we had attempted to obtain the first direct measurement of Kdo-N3 into LPS by MS using the ΔwaaC E. coli strain but were unsuccessful. After detection of the second LPS species in ClearColi K-12 upon Kdo-N3 supplementation, we hypothesized that the faster-migrating Kdo-N3–containing lipid A species (Kdo-N3–lipid IVA or (Kdo-N3)2–lipid IVA) should be extractable by Bligh–Dyer extraction and detectable by MS as reported for deep-rough LPS (33, 34). Thus, ClearColi was grown with and without Kdo-N3 supplementation followed by the lipid isolation by acidic Bligh–Dyer extraction (35).

The total lipid extracts were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. The corresponding LPS ions from ClearColi K-12 (with or without Kdo-N3) are summarized in Table 1 with calculated m/z values and observed m/z values (when found). The negative ion mode spectra of both samples showed the most abundant ion at m/z 1403.8 (supplemental Fig. S5, A and B). This peak can be attributed to lipid IVA ([M − H]− ion), the major LPS component expressed by ClearColi (31, 32). In the ClearColi sample supplemented with Kdo-N3 (red trace), peaks were observed at m/z 1893.9 (Fig. 5B) and m/z 1648.8 (Fig. 5A). Those peaks were not detected for the ClearColi sample grown without Kdo-N3 (blue trace). The peak at m/z 1893.9 is consistent with (Kdo-N3)2-lipid IVA ([M − H]− ion), whereas the peak at m/z 1648.8 can be attributed to Kdo-N3–lipid IVA. MS/MS fragmentation of both ions (1648.8 and 1893.9) produced a fragment ion of m/z 1403.8 (supplemental Fig. S6, A–D). This fragment ion peak is consistent with lipid IVA formed by the loss of one or two Kdo-N3 units, respectively.

Table 1.

Observed lipid IVA species in total lipid extracts of ClearColi K-12 evaluated by MALDI-TOF-MS

The data are representative of two independent experiments.

| LPS species | Calculated mass [M − H]− (m/z) | Observed mass [M − H]− (m/z) | Relative signal intensity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ClearColi | |||

| Lipid IVA | 1403.85 | 1403.80 | 100 |

| Kdo-lipid IVA | 1623.90 | 1623.83 | 0.11 |

| Kdo-N3-lipid IVA | 1648.91 | NDa | ND |

| (Kdo)2-lipid IVA | 1843.96 | ND | ND |

| Kdo-Kdo-N3-lipid IVA | 1868.97 | ND | ND |

| (Kdo-N3)2-lipid IVA | 1893.98 | ND | ND |

| ClearColi grown with 1 mm Kdo-N3 | |||

| Lipid IVA | 1403.85 | 1403.80 | 100 |

| Kdo-lipid IVA | 1623.90 | 1623.83 | 0.10 |

| Kdo-N3-lipid IVA | 1648.91 | 1648.84 | 0.48 |

| (Kdo)2-lipid IVA | 1843.96 | ND | ND |

| Kdo-Kdo-N3-lipid IVA | 1868.97 | ND | ND |

| (Kdo-N3)2-lipid IVA | 1893.98 | 1893.89 | 0.02 |

a ND, not detected.

Figure 5.

MALDI-TOF MS spectra of total lipid extracts from ClearColi K-12 grown in the absence or presence of Kdo-N3. The total lipid extracts from ClearColi were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS in the negative mode. A zoom-in is shown for the regions containing the [M − H]− ions of Kdo-N3–lipid IVA (A) and (Kdo-N3)2–lipid IVA (B). The spectra were normalized to the highest-abundance ion (lipid IVA) and overlaid. The red spectrum corresponds to cells grown with Kdo-N3, and blue corresponds to cells grown without Kdo-N3. The spectra shown are representative of two independent experiments.

Interestingly, a low-intensity signal was observed at m/z 1623.83 in both samples, which can be interpreted as Kdo-lipid IVA (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S5D). MS/MS fragmentation of this ion led also to m/z 1403.8, indicating the loss of one Kdo unit to form lipid IVA. A peak at m/z 1843.96, which would be consistent with (Kdo)2-lipid IVA, was not observed. Whereas ClearColi K-12 is reported to lack the ability to synthesize Kdo, these results suggest that there is a trace amount of Kdo present in the growth medium or produced endogenously by the strain. Trace amounts of Kdo have been previously reported in ClearColi K-12 in a different context (32).

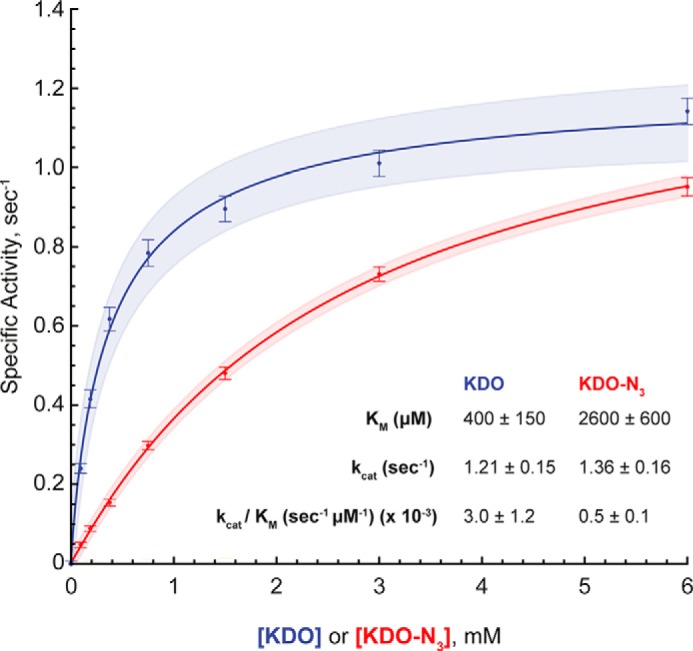

CMP-Kdo synthetase (KdsB) substrate selectivity for Kdo over Kdo-N3

The results from the ClearColi samples obtained by SDS-PAGE and MALDI-MS indicate that the uptake and incorporation of Kdo-N3 are significantly less efficient than for Kdo. The first step necessary for Kdo-N3 incorporation after its uptake is the formation of CMP–Kdo-N3 by the Kdo cytidylyltransferase KdsB (Fig. 1A; see also supplemental Fig. S7). In KdtA biochemical assays when CMP-Kdo levels are low, KdtA has been observed to transfer a single Kdo instead of two (36). We hypothesized that KdsB does not efficiently recognize Kdo-N3, leading to low levels of CMP–Kdo-N3, which would limit the production of (Kdo-N3)2-lipid IVA and core-lipid IVA and would be an explanation for the detection of Kdo-N3–lipid IVA by MS. To test this hypothesis, KdsB was overexpressed in E. coli and purified. The activity of KdsB was analyzed using the EnzChek pyrophosphate assay kit to detect pyrophosphate released during the reaction of CTP and Kdo sugar (see supplemental Fig. S7A). The apparent Km values for Kdo and Kdo-N3 were measured at fixed saturating concentrations of CTP and Mg2+ at pH 7.6. We found that the apparent Km was substantially higher (suggesting weaker binding) for Kdo-N3 compared with its native substrate Kdo (Km = 400 ± 150 μm for Kdo, Km = 2600 ± 600 μm for Kdo-N3, 95% confidence interval). Conversely, the kcat did not differ substantially with the addition of the azido group (kcat = 1.21 ± 0.15 s−1 for Kdo, kcat = 1.36 ± 0.16 s−1 for Kdo-N3, 95% confidence interval) (see Fig. 6). The specificity constant (kcat/Km) for Kdo (3.0 ± 1.2 × 10−3 s−1 μm−1) was about 6-fold higher than for Kdo-N3 (0.5 ± 0.1 × 10−3 s−1 μm−1), indicating that KdsB substrate specificity may contribute to the observed level of Kdo-N3 incorporation into ClearColi K-12 LPS.

Figure 6.

Kinetic studies of KdsB with Kdo or Kdo-N3 as substrate. Specific activity of KdsB with Kdo (blue curve) or Kdo-N3 (red curve) as the sugar substrate with saturating CTP. Kinetic parameters, generated by a fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation, are displayed below the curves. Shaded areas, 95% confidence interval for the fit. The data show a similar kcat for each sugar, whereas the Km increased noticeably for Kdo-N3. Error bars, S.E. Kinetic parameters are reported ± 95% confidence interval. The data were obtained in two independent experiments done in biological triplicates.

Discussion

In the LPS of many Gram-negative bacteria, the first core sugar attached to lipid A is Kdo (8). This makes Kdo an attractive handle to investigate LPS biosynthesis, transport, and assembly. Previous work by Vauzeilles and co-workers showed that Gram-negative bacteria can be labeled by treatment with an exogenous Kdo analog, Kdo-N3, followed either by a copper-catalyzed click reaction with a fluorescent reagent (16) or a copper-free click reaction with a biotinylated reagent and detection with a fluorescent antibody (17). We have replicated the incorporation of Kdo-N3 in E. coli and extended the detection method to include the fluorescent copper-free click reagent Alexa488-DIBO, which allows for single-reagent, single-step detection. Furthermore, we optimized the time course and dose-response of Kdo-N3 incorporation by utilizing flow cytometry detection of Alexa488-DIBO labeling of Kdo-N3–treated cells. Flow cytometry provided an efficient and quantitative way to determine that relatively long Kdo-N3 incubation times (≥4 h) and high exogenous doses (>100 μm) were needed to see robust labeling of E. coli cells. Our findings are in agreement with the results reported by Vauzeilles and co-workers (16, 17). Depending on the experiment, they described overnight (12- or 16-h) incubation with 1 or 4 mm Kdo-N3, respectively, or a shorter incubation time (2 h) with a very high Kdo-N3 concentration (25 mm). The time and high Kdo-N3 concentration needed for sufficient Kdo-N3 incorporation are a potential limitation when employing this technique for investigating LPS biosynthesis or transport.

Previous results suggested that the Kdo-N3–dependent labeling of Gram-negative bacteria was localized to the cell envelope, with localization presumed to be the outer leaflet of the OM (16, 17). To confirm the localization, we utilized plasmolysis of fluorescently labeled E. coli to show that the Alexa488-DIBO is indeed present in the OM (Fig. 2). Although LPS is transiently present in both leaflets of the IM, it is not present on the inner leaflet of the OM (21). Whereas these observations are consistent with Kdo-N3 incorporation into LPS and externalization on the outer leaflet of the OM, the Alexa488-DIBO reagent was not expected to penetrate into the periplasm or cytoplasm of intact cells due to its size (>800 Da) (5), hydrophobicity, and rigidity. Further molecular evaluation was needed to confirm Kdo-N3 incorporation into LPS and externalization.

The first direct evidence of Kdo-N3 incorporation into LPS was provided by SDS-PAGE separation of the LPS from fluorescently labeled rough and deep-rough ΔwaaC E. coli. The gels indicated that the Alexa488-DIBO was covalently bound to Kdo-N3, which was incorporated into rough LPS and deep-rough LPS, respectively (Fig. 3). The ability to image and stain the same gel for Kdo-N3-Alexa488-DIBO, in addition to proteins and total LPS, allows enhanced specificity for Kdo-N3–containing LPS.

Although we showed Kdo-N3 incorporation into the LPS, it was difficult to determine the level of incorporation due to the endogenous Kdo biosynthesized in the E. coli K-12 and ΔwaaC E. coli strains. The competition between endogenous Kdo and exogenously supplied Kdo-N3 may also contribute to the long incubation time necessary for sufficient Kdo-N3 labeling (≥4 h for flow cytometry, ≥ 3 h for SDS-PAGE) compared with the doubling time of E. coli cells (20–30 min). We turned instead to a strain (ClearColi K-12) that lacks endogenous Kdo biosynthesis. Using ClearColi K-12, we demonstrated that externally supplemented Kdo can enter an E. coli strain and restore core-LPS biosynthesis, bypassing the existing mutations in the strain (Fig. 4). To our knowledge, the uptake and incorporation of exogenous Kdo in LPS have not previously been reported. The ability to restore Kdo to strains lacking Kdo biosynthetic gene(s) offers a new opportunity to evaluate the role of Kdo in OM assembly and permeability in vitro as well as in animal models of colonization/pathogenesis. It is possible that sufficient Kdo would be available from the microbiome or dietary sources (20, 37) to sustain bacteria deficient in Kdo biosynthesis in mammalian hosts. A similar restoration of core-LPS was expected upon Kdo-N3 supplementation. Surprisingly, ClearColi produced only a small amount of core-LPS upon Kdo-N3 supplementation, with a greater amount of a second, faster-migrating LPS species (Fig. 4). MALDI-TOF MS analysis of ClearColi K-12 total lipid extracts confirmed the presence of Kdo-N3–lipid IVA and (Kdo-N3)2–lipid IVA (Fig. 5 and Table 1), thus providing the first direct proof of Kdo-N3 addition to lipid IVA. We also tried to detect Kdo-N3–lipid A or (Kdo-N3)2–lipid A in total lipid extracts from ΔwaaC E. coli grown in the presence of Kdo-N3 by MALDI-MS and electrospray ionization-TOF MS. Unfortunately, the level of Kdo-N3 was below the limit of detection, and we could only detect Kdo2-lipid A.

When comparing the results for the addition of exogenous Kdo and Kdo-N3 (Fig. 4), Kdo-N3 incorporation into LPS seems to be generally low (<1% of naturally occurring LPS), indicating that Kdo-N3 differs from Kdo in at least one node during its uptake and incorporation into the LPS. CMP-Kdo synthetase (KdsB) definitely contributes to the poor incorporation. We obtained the steady-state kinetics for KdsB with Kdo and Kdo-N3 in vitro showing that the specificity constant is ∼6-fold higher for Kdo than for Kdo-N3, due exclusively to differences in Km (Fig. 6). This suggests that the CMP–Kdo-N3 concentration in the cytoplasm is lower than the CMP-Kdo concentration in ClearColi supplemented with Kdo-N3 or Kdo, respectively, which partially explains the low level of core-(Kdo-N3)2-LPS. It is also possible that the Kdo transferase KdtA inefficiently adds Kdo-N3 to lipid IVA (and/or Kdo-N3–lipid IVA) due to inefficient utilization of CMP–Kdo-N3 or Kdo-N3–lipid IVA. A presumably short half-life of CMP–Kdo-N3 in aqueous environments (38) would limit any accumulation of CMP–Kdo-N3 for use by KdtA. The core heptosyltransferase WaaC may not efficiently recognize (Kdo-N3)2–lipid IVA relative to Kdo2-lipid IVA (see Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S7). However, the presence of Kdo-N3–lipid IVA suggested that the problem occurred earlier in the pathway than WaaC (Fig. 1A). Last, the rate of Kdo-N3 uptake might be slower than that of Kdo, which would lead to a low intracellular level of Kdo-N3, ultimately reducing synthesis of core-(Kdo-N3)2-LPS. The Kdo and Kdo-N3 uptake mechanism(s) have not been reported.

The analysis of Kdo-N3 incorporation into ClearColi K-12 uncovered inefficient metabolic incorporation of Kdo-N3 relative to Kdo and interference with core-LPS biosynthesis (Fig. 4). While these results were obtained in ClearColi, the results, including the KdsB studies, suggest that Kdo-N3 metabolic incorporation (and possibly uptake) is limited in all E. coli strains. Because of endogenous Kdo, the limitations were not as obvious in the other E. coli strains tested. Whereas Kdo-N3 can be incorporated at sufficient levels to serve as a valuable tracer of LPS biosynthesis and transport (Figs. 2 and 3 and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3), it is important to be aware of the differences between Kdo and Kdo-N3 incorporation and certain limitations arising from these findings. The results will be helpful when employing this method for investigating the LPS biosynthesis, transport, and assembly.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All strains in this study were E. coli K-12 strains lacking O-antigen. ClearColi K-12 was obtained from Lucigen. The strains were grown either in lysogeny broth (LB, containing 10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, 5 g/liter NaCl, pH 7.5, adjusted with 6 m HCl and 6 m NaOH as needed) or M9 minimal medium (M9 medium, containing 0.3% KH2PO4, 0.6% Na2HPO4, 0.5% NaCl, 0.1% NH4Cl, 2 mm MgSO4, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 0.2% maltose, sterile-filtered) as indicated below.

E. coli K-12 mCherry (TUT0018) strain construction

The lacI gene was replaced with a chloramphenicol resistance cassette in strain MG1655 using the λRED system and pKD3 as described previously (39). The chloramphenicol resistance gene was removed by pFLP2 (40) that harbors FLP recombinase to recombine the FRT sites flanking the cassette. The DNA fragment encoding Plac::mCherry, synthesized by GeneArt Gene Strings (Thermo Fisher Scientific), was cloned into the EcoRI-HindIII site of the pCAH63(41), and the constructed plasmid was integrated at the λ attachment site in the genome using the CRIM system (41). The final strain genotype was ΔlacI attλ(Plac::mCherry) and was confirmed by PCR.

Synthesis of Kdo-N3

Kdo-N3 was synthesized by adapting and modifying the method described by Mikula et al. (19) for the synthesis of Kdo. The synthesis of Kdo-N3 is described in detail in the supplemental methods.

Copper-free click reaction

Typically, a bacterial overnight culture was inoculated into LB or M9 medium containing an appropriate volume of a sterile aqueous stock solution of Kdo-N3 or the same volume of sterile water to a starting A600 of 0.002–0.005. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C at 225 rpm for the indicated period of time (to stationary phase), pelleted at 11,600 × g for 2 min, and washed three times with M9 medium. For the click reaction, the pellets were resuspended in M9 medium, and Alexa488-DIBO (50 mm stock solution in DMSO) was added to a final concentration of 0.25 mm. All samples were reacted for 1 h at 37 °C at 225 rpm in the dark. After the click reaction, the cells were pelleted and washed three times with M9 medium. The cell pellets were prepared for fluorescence microscopy, plasmolysis, flow cytometry or SDS-PAGE.

Fluorescence microscopy imaging

E. coli samples were grown in LB medium and click-labeled as described. A 3-μl aliquot of the live, fluorescently labeled E. coli samples, diluted in M9 medium, was deposited onto a thin, 1.2% agar pad, which was prepared on a glass microscope slide. The cells were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope with a Nikon halogen illuminator (D-LH/LC), a Sola light engine from Lumencor, and a Clara Interline CCD camera from Andor. A Nikon CFI Plan Apo Lambda DM ×100 oil objective lens (1.45 numerical aperture) was used for phase-contrast and fluorescent imaging. GFP images were taken by using the FITC-5050A-NTE-ZERO filter set (Semrock). mCherry images were taken by using the TRITC-B-NTE-NEZO filter set (Semrock). Images were captured by using Nikon Elements software and exported for figure preparation in ImageJ (42).

Plasmolysis

For plasmolysis, samples of E. coli mCherry (TUT0018) and E. coli K-12 (BW25113) were grown in M9 with Kdo-N3 and fluorescently labeled as described above. After imaging the non-plasmolyzed cells for fluorescence, the samples were pelleted at 11,600 × g for 2 min, resuspended in 100 μl of plasmolysis solution (containing 15% sucrose, 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 20 mm sodium azide), and deposited on an agar pad (containing 15% sucrose and 1.2% agarose) freshly prepared on a glass microscope slide and directly imaged (26, 43). For membrane staining of E. coli K-12, FM 4-64 ((N-3-triethylammoniumpropyl)-4-(6-(4-(diethylamino)phenyl)hexatrienyl)-pyridinium dibromide (Invitrogen); 500 μg/ml in DMSO) was added to the plasmolyzed sample to a final concentration of 1% (v/v) before depositing a 3-μl aliquot on an agar pad.

SDS-PAGE and LPS visualization

Aliquots of 500 μl of E. coli samples were diluted in SDS sample buffer (normalized such that 50 μl of the resuspended samples contained the equivalent of 1 ml of cells at an A600 of 0.5), applied to a Novex 16% Tricine protein gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and imaged for green fluorescence on a Typhoon 9400 imager (GE Healthcare). The same gel was processed with the Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS stain kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), as described previously (27). The LPS bands were visualized under UV light in a ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad) with Image Lab version 3.0 software (Qdots525). To verify equal sample loading, the same gel was subsequently stained with Coomassie Blue (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Preparation of total lipid extract from ClearColi K-12

A ClearColi K-12 (Lucigen) culture was inoculated in 50 ml of LB in the presence or absence of 1 mm Kdo or 1 mm Kdo-N3 and grown to an A600 of ∼1.9 at 37 °C at 225 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3950 × g for 20 min and washed once with 50 ml of PBS (pH 7.4). The cell pellets were resuspended in a glass centrifuge tube in 2 ml of 0.1 mm aqueous HCl, and a single-phase Bligh/Dyer mixture (34, 35) was prepared by adding 5 ml of methanol and 2.5 ml of chloroform. Phospholipids and lipid IVA species were extracted by shaking on a rocker for 1 h at room temperature. The supernatant was converted to a two-phase Bligh-Dyer solution by adding 2.5 ml of 0.1 mm HCl and 2.5 ml of chloroform. After centrifugation at 1000 × g for 20 min at room temperature to separate the two phases, the lower phase (predominantly chloroform) was isolated with a glass pipette and dried down under a stream of nitrogen. The samples were stored at −80 °C until needed.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

MS experiments were carried out on a Sciex 5800 MALDI TOF/TOF instrument equipped with a Nd:YAG laser operating at 355 nm. MS and MS/MS spectra were acquired in negative ion mode. MS/MS spectra were acquired using a 1-kV negative ion method and air as the collision gas. Total lipid extract samples were diluted in chloroform/methanol (4:1, v/v, ∼500 μg extract/ml). The matrix solution was prepared as a saturated solution of 6-aza-2-thiothymine in 45% acetonitrile with 1% dibasic ammonium citrate (44). The MALDI sample was prepared by drying 0.5 μl of the matrix solution on the MALDI target and then spotting 0.5 μl of the total lipid extract sample on top of the dried matrix. Spectra were processed using Data Explorer (Sciex) and mMass software (45).

Pyrophosphate release assay

Activity of KdsB was measured using the EnzChek pyrophosphate assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Briefly, conversion of CTP to CMP-Kdo (or CMP–Kdo-N3) + PPi by KdsB was coupled with the conversion of PPi to 2Pi by pyrophosphatase and subsequent conversion of the reagent 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methyl-purine ribonucleoside to ribose 1-phosphate and 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methyl-purine by purine nucleoside phosphorylase. 2-Amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine has a characteristic peak absorption at 360 nm, which was measured during the course of the assay in a plate reader. Absorption values were converted to absolute concentrations of PPi generated by use of a standard curve (provided with the kit) produced from varying concentrations of Na2P2O7. Kdo and Kdo-N3 concentrations ranged from a maximum of 3 mm to 47 μm by 2-fold dilution. CTP (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and MgSO4 were kept constant at 5 mm across all conditions. KdsB was added at 50 nm. Rates of pyrophosphate production were determined by measuring the slope of the absorption increase versus time near the beginning of the assay, when such increases were linear (i.e. before depletion of any of the assay reagents), and comparing these slopes with the standard curve. Data were fit to standard Michaelis–Menten kinetics in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA), which also generated 95% confidence intervals for the hits. Importantly, the assay was very sensitive to phosphate contaminations. Several lots of CTP (from Sigma-Aldrich and Thermo Fisher Scientific) were tested before performing this experiment, as it was our experience that many commercially available preparations of CTP were contaminated with phosphate. The CTP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Product R0451, lot 00466743) that we ultimately used for this experiment showed no apparent phosphate contamination (data not shown).

Author contributions

I. N., D. D., K. G., and T. U. conducted the experiments and analyzed the results. D. D. conducted the KdsB studies and analyzed the results. K. G. conducted the MALDI-MS experiments and analyzed the data. T. U. conducted and supervised the microscopy experiments. I. N., G. L., and D. A. S. planned the experiments and conceived the idea for this project. I. N. and D. A. S. wrote the paper with input and approval of all authors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pramila Tamrakar for constructing E. coli mCherry. We thank Dazhi Tang for the analysis of Kdo-N3by LC-electrospray ionization-MS. We thank Joe Lam, Naomi Rajapaksa, Dita Rasper, and Naomi Kreamer for support. We thank Thomas Krucker, Laura McDowell, Chris Rath, and Will Sawyer for helpful discussions. We thank Zach Sweeney for early input.

K. G., D. D., T. U., G. L., and D. A. S. are full-time employees of Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research (NIBR).

This paper is dedicated to the legacy of Christian R. H. Raetz (1946 -2011), discoverer of the Raetz pathway of lipid A biosynthesis and mentor to D. A. S.

This article contains supplemental Methods, Table S1, and Figs. S1–S7.

- OM

- outer membrane

- IM

- inner membrane

- Alexa488-DIBO

- Click-IT Alexa Fluor 488-DIBO alkyne

- FM-4-64

- ((N-3-triethylammoniumpropyl)-4-(6-(4-(diethylamino)phenyl)hexatrienyl)-pyridinium dibromide

- Kdo

- 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid

- Kdo-N3

- 8-azido-3,8-dideoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid

- KdsB

- Kdo cytidylyltransferase

- KdtA

- Kdo transferase

- LB

- lysogeny broth

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- WaaC

- core heptosyltransferase.

References

- 1. Yılmaz C., and Özcengiz G. (2017) Antibiotics: pharmacokinetics, toxicity, resistance and multidrug efflux pumps. Biochem. Pharmacol. 133, 43–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khan A. U., Maryam L., and Zarrilli R. (2017) Structure, genetics and worldwide spread of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM): a threat to public health. BMC Microbiol. 17, 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ventola C. L. (2015) The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 2: management strategies and new agents. P T 40, 344–352 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li X. Z., Plésiat P., and Nikaido H. (2015) The challenge of efflux-mediated antibiotic resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 337–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nikaido H. (2003) Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 593–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nikaido H., and Vaara M. (1985) Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol. Rev. 49, 1–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raetz C. R., and Whitfield C. (2002) Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 635–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whitfield C., and Trent M. S. (2014) Biosynthesis and export of bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83, 99–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zughaier S. M., Tzeng Y. L., Zimmer S. M., Datta A., Carlson R. W., and Stephens D. S. (2004) Neisseria meningitidis lipooligosaccharide structure-dependent activation of the macrophage CD14/Toll-like receptor 4 pathway. Infect. Immun. 72, 371–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moison E., Xie R., Zhang G., Lebar M. D., Meredith T. C., and Kahne D. (2017) A fluorescent probe distinguishes between inhibition of early and late steps of lipopolysaccharide biogenesis in whole cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 928–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carroll L., Evans H. L., Aboagye E. O., and Spivey A. C. (2013) Bioorthogonal chemistry for pre-targeted molecular imaging: progress and prospects. Org. Biomol. Chem. 11, 5772–5781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jewett J. C., and Bertozzi C. R. (2010) Cu-free click cycloaddition reactions in chemical biology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1272–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li L., and Zhang Z. (2016) Development and applications of the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) as a bioorthogonal reaction. Molecules 10.3390/molecules21101393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kocaoglu O., and Carlson E. E. (2016) Progress and prospects for small-molecule probes of bacterial imaging. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 472–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siegrist M. S., Swarts B. M., Fox D. M., Lim S. A., and Bertozzi C. R. (2015) Illumination of growth, division and secretion by metabolic labeling of the bacterial cell surface. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 184–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dumont A., Malleron A., Awwad M., Dukan S., and Vauzeilles B. (2012) Click-mediated labeling of bacterial membranes through metabolic modification of the lipopolysaccharide inner core. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 3143–3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fugier E., Dumont A., Malleron A., Poquet E., Mas Pons J., Baron A., Vauzeilles B., and Dukan S. (2015) Rapid and specific enrichment of culturable Gram negative bacteria using non-lethal copper-free click chemistry coupled with magnetic beads separation. PLoS One 10, e0127700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang W., Zhu Y., and Chen X. (2017) Selective imaging of Gram-negative and Gram-positive microbiotas in the mouse gut. Biochemistry 56, 3889–3893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mikula H., Blaukopf M., Sixta G., Stanetty C., and Kosma P. (2014) Synthesis of ammonium 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulopyranosylonate (ammonium Kdo). In Carbohydrate Chemistry: Proven Synthetic Methods (van der Marel G., and Codee J., eds), Volume 2, pp. 207–212, CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smyth K. M., and Marchant A. (2013) Conservation of the 2-keto-3-deoxymanno-octulosonic acid (Kdo) biosynthesis pathway between plants and bacteria. Carbohydr. Res. 380, 70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Okuda S., Sherman D. J., Silhavy T. J., Ruiz N., and Kahne D. (2016) Lipopolysaccharide transport and assembly at the outer membrane: the PEZ model. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 337–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liechti G. W., Kuru E., Hall E., Kalinda A., Brun Y. V., VanNieuwenhze M., and Maurelli A. T. (2014) A new metabolic cell-wall labelling method reveals peptidoglycan in Chlamydia trachomatis. Nature 506, 507–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ning X., Guo J., Wolfert M. A., and Boons G. J. (2008) Visualizing metabolically labeled glycoconjugates of living cells by copper-free and fast huisgen cycloadditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 2253–2255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rajapaksha R. M., Tobor-Kapłon M. A., and Bååth E. (2004) Metal toxicity affects fungal and bacterial activities in soil differently. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 2966–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cook W. R., MacAlister T. J., and Rothfield L. I. (1986) Compartmentalization of the periplasmic space at division sites in Gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 168, 1430–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lewenza S., Vidal-Ingigliardi D., and Pugsley A. P. (2006) Direct visualization of red fluorescent lipoproteins indicates conservation of the membrane sorting rules in the family Enterobacteriaceae. J. Bacteriol. 188, 3516–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davis M. R. Jr., and Goldberg J. B. (2012) Purification and visualization of lipopolysaccharide from Gram-negative bacteria by hot aqueous-phenol extraction. J. Vis. Exp. 10.3791/3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brabetz W., Müller-Loennies S., Holst O., and Brade H. (1997) Deletion of the heptosyltransferase genes rfaC and rfaF in Escherichia coli K-12 results in an Re-type lipopolysaccharide with a high degree of 2-aminoethanol phosphate substitution. Eur. J. Biochem. 247, 716–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raetz C. R., Garrett T. A., Reynolds C. M., Shaw W. A., Moore J. D., Smith D. C. Jr., Ribeiro A. A., Murphy R. C., Ulevitch R. J., Fearns C., Reichart D., Glass C. K., Benner C., Subramaniam S., Harkewicz R., et al. (2006) Kdo2-Lipid A of Escherichia coli, a defined endotoxin that activates macrophages via TLR-4. J. Lipid Res. 47, 1097–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang Z., Wang J., Ren G., Li Y., and Wang X. (2015) Influence of core oligosaccharide of lipopolysaccharide to outer membrane behavior of Escherichia coli. Mar. Drugs 13, 3325–3339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mamat U., Wilke K., Bramhill D., Schromm A. B., Lindner B., Kohl T. A., Corchero J. L., Villaverde A., Schaffer L., Head S. R., Souvignier C., Meredith T. C., and Woodard R. W. (2015) Detoxifying Escherichia coli for endotoxin-free production of recombinant proteins. Microb. Cell Fact. 14, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meredith T. C., Aggarwal P., Mamat U., Lindner B., and Woodard R. W. (2006) Redefining the requisite lipopolysaccharide structure in Escherichia coli. ACS Chem. Biol. 1, 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moon K., Six D. A., Lee H. J., Raetz C. R., and Gottesman S. (2013) Complex transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of an enzyme for lipopolysaccharide modification. Mol. Microbiol. 89, 52–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Six D. A., Carty S. M., Guan Z., and Raetz C. R. (2008) Purification and mutagenesis of LpxL, the lauroyltransferase of Escherichia coli lipid A biosynthesis. Biochemistry 47, 8623–8637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhao J., and Raetz C. R. (2010) A two-component Kdo hydrolase in the inner membrane of Francisella novicida. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 820–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Belunis C. J., and Raetz C. R. (1992) Biosynthesis of endotoxins: purification and catalytic properties of 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid transferase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 9988–9997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dumont M., Lehner A., Vauzeilles B., Malassis J., Marchant A., Smyth K., Linclau B., Baron A., Mas Pons J., Anderson C. T., Schapman D., Galas L., Mollet J. C., and Lerouge P. (2016) Plant cell wall imaging by metabolic click-mediated labelling of rhamnogalacturonan II using azido 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid. Plant J. 85, 437–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin C. H., Murray B. W., Ollmann I. R., and Wong C. H. (1997) Why is CMP-ketodeoxyoctonate highly unstable? Biochemistry 36, 780–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Datsenko K. A., and Wanner B. L. (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hoang T. T., Karkhoff-Schweizer R. R., Kutchma A. J., and Schweizer H. P. (1998) A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212, 77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haldimann A., and Wanner B. L. (2001) Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6384–6393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S., and Eliceiri K. W. (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paradis-Bleau C., Markovski M., Uehara T., Lupoli T. J., Walker S., Kahne D. E., and Bernhardt T. G. (2010) Lipoprotein cofactors located in the outer membrane activate bacterial cell wall polymerases. Cell 143, 1110–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kanipes M. I., Lin S., Cotter R. J., and Raetz C. R. (2001) Ca2+-induced phosphoethanolamine transfer to the outer 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid moiety of Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide: a novel membrane enzyme dependent upon phosphatidylethanolamine. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1156–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Strohalm M., Hassman M., Kosata B., and Kodícek M. (2008) mMass data miner: an open source alternative for mass spectrometric data analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 22, 905–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gu Y., Stansfeld P. J., Zeng Y., Dong H., Wang W., and Dong C. (2015) Lipopolysaccharide is inserted into the outer membrane through an intramembrane hole, a lumen gate, and the lateral opening of LptD. Structure 23, 496–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.