Abstract

Introduction

COPD has complex etiologies involving both genetic and environmental determinants. Among genetic determinants, the most recognized is a severe PiZZ (Glu342Lys) inherited alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD). Nonetheless, AATD patients present a heterogeneous clinical evolution, which has not been completely explained by sociodemographic or clinical factors. Here we performed the gene expression profiling of blood cells collected from mild and severe COPD patients with PiZZ AATD. Our aim was to identify differences in messenger RNA (mRNA) and microRNA (miRNA) expressions that may be associated with disease severity.

Materials and methods

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 12 COPD patients with PiZZ AATD (6 with severe disease and 6 with mild disease) were used in this pilot, high-throughput microarray study. We compared the cellular expression levels of RNA and miRNA of the 2 groups, and performed functional and enrichment analyses using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene-ontology (GO) terms. We also integrated the miRNA and the differentially expressed putative target mRNA. For data analyses, we used the R statistical language R Studio (version 3.2.5).

Results

The severe and mild COPD–AATD groups were similar in terms of age, gender, exacerbations, comorbidities, and use of augmentation therapy. In severe COPD–AATD patients, we found 205 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (114 upregulated and 91 downregulated) and 28 miRNA (20 upregulated and 8 downregulated) compared to patients with mild COPD–AATD disease. Of these, hsa-miR-335-5p was downregulated and 12 target genes were involved in cytokine signaling, MAPK/mk2, JNK signaling cascades, and angiogenesis were much more highly expressed in severe compared with mild patients.

Conclusions

Despite the small sample size, we identified downregulated miRNA (hsa-miR-335) and the activation of pathways related to inflammation and angiogenesis on comparing patients with severe vs mild COPD–AATD. Nonetheless, our findings warrant further validation in large studies.

Keywords: alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, COPD, gene expression, miRNAs, integrative analysis

Introduction

COPD is the third leading cause of death worldwide. It is a complex disease influenced by both genetic and environmental determinants, the most important of which is cigarette smoking. However, only 10%–20% of smokers develop clinically significant disease, and there is a significant variability across the smokers with similar cigarette exposure. Some of these heterogeneities may be the result of genetic variations.1

A known genetic risk factor for COPD is severe alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD). SERPINA1 is the gene responsible for the synthesis of the AAT protein, which is a serine protease inhibitor (serpin) and an acute-phase glycoprotein.2 Normal serum AAT levels are the result of 2 copies of the common M allele of the SERPINA1 gene. The M allele of AAT is present in >90% of the population, and is called Pi*M. Over 100 SERPINA1 mutations have been identified to date, but only some are implicated in disease pathogenesis. The most frequent deficient alleles are S (Glu264Val) and Z (Glu342Lys), which are called Pi*S and Pi*Z, respectively. In particular, carriers of 2 Z alleles (PiZZ) have strongly reduced circulating levels of AAT (up to 10%–20% of normal, which is 1.3–2 g/L). Because of Z AAT misfolding and intracellular accumulation, the Z allele is the major contributor to pulmonary emphysema and liver disease in people of European ancestry.3–4

The evolution of emphysema in clinical terms and life expectancy are directly related to the accelerated loss of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1). Previous studies identified tobacco consumption and exacerbations as the main factors related to FEV1 decline.5 Lung function decline is faster in AATD compared with non-AATD COPD patients, although this is not homogeneous in all individuals.6–8

Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and meta-analyses of GWAS have begun to shed light on biological pathways that contribute to the development of COPD.9–11 The analysis of the miRNA expression is increasingly used in clinical research. miRNAs belong to the family of small non-coding RNAs (~21–25 nucleotides long), but they are involved in mRNA regulation.12 miRNAs modulate gene expression by either destabilizing transcripts or inhibiting protein translation. In fact, miRNAs may target up to one-third of the transcriptome. Therefore, miRNA expression patterns in cells and tissues are considered to be biomarkers for both the diagnosis and prognosis of different diseases, including COPD.13–16 mRNA and miRNA signatures can assist clinicians in prognosis assessment and therapeutic approaches.12–18 However, the heterogeneity in study designs makes comparisons across studies difficult. Therefore, this field is naturally progressing toward the integration of miRNA with gene expression.19

In this context, some SERPINA1 gene expression studies have been performed.6 We propose that gene expression profiling may provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms of AATD-related COPD and eventually lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets.20–21 Here, we explored the use of gene expression patterns in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected from PiZZ cases with severe and mild COPD. We aimed to identify differentially expressed putative mRNA and miRNAs in PBMCs isolated from patients with different severities of lung disease.

Materials and methods

Design and study sample

This study was a pilot high-throughput microarray experiment. On the basis of the presence of poor lung function at diagnosis (FEV1<45% predicted), we included 6 patients considered to have rapid progression of emphysema (severe disease group). This severe group was compared with a group of 6 subjects matched for age and gender but with significantly better lung function at diagnosis (FEV1>65% predicted). We considered these patients to have slow disease progression (mild disease group). All the patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic of the respiratory department of the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital (Barcelona, Spain) and all had undergone genotyping by sequencing of all coding exons of SERPINA1. Signed informed consent was obtained from all subjects for participation in the study, and the study was approved (project ID: PR (AG)157/2016) by the Ethics Committee of the Research Institute of Hospital Vall d´Hebron (Barcelona, Spain).

All the patients presented clinical stability, defined as no respiratory ambulatory exacerbations or hospital admission in the previous 2 months. They were followed and treated according to guidelines.22 Some patients were receiving intravenous therapy with plasma purified AAT (Prolastin or Trypsone; Grifols, Barcelona, Spain) at a dose of 120 mg/kg for 15 days.

As previous studies have shown that AAT therapy may indirectly reduce the expression of Z-AAT,23 blood samples were taken immediately before the next infusion in patients receiving augmentation therapy.

Variables and data collection

Sociodemographic, clinical (phenotype, age at diagnosis, current age, age at onset of symptoms, tobacco consumption, comorbidities, exacerbations, and treatments), and lung function data at the time of AATD diagnosis were collected from medical records. Lung function tests were performed according to standardized recommendations and international guidelines.24–25

Blood processing and RNA isolation

Blood processing and RNA isolation was carried out at the Biobank at the Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain. PBMCs were isolated from AATD patients using Ficoll gradient centrifugation. Total RNA and miRNA were isolated from PBMCs using the QuickGene RNA tissue SII (RT-S2) kit and QuickGene 810 FUJIFILM device. miRNA was also isolated from PBMCs using QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the miRNeasy Mini Handnook Kit (Qiagen). RNA and miRNA concentrations were determined with a NanoDrop ND2000 spectrophotometer and quality was checked using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Hilden, Germany) with Eukariotic NanoChip before microarray analysis.

RNA and miRNA microarray hybridization

The RNA and miRNA microarrays were performed at the High Technology Unit (UAT) of the VHIR. In this experiment, the Affymetrix GeneTitan microarray platform and the Genechip Human Gene Array Plate 2.1 were used for RNA hybridization. This array analyzes gene expression patterns on a whole-genome scale on a single array with probes covering many exons on the target genomes, thereby providing expression summarization at the exon or gene level. The starting material was 200 ng of total RNA of each sample. Briefly, sense single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) suitable for labeling was generated from total RNA with the GeneChip WT Plus Reagent Kit from Affymetrix (High Wycomb, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sense ssDNA was fragmented, labeled, and hybridized to the arrays with the GeneChip WT Terminal Labeling and Hybridization Kit from the same manufacturer.

The Affymetrix GeneTitan microarray platform and the Genechip miRNA array plate 4.1 were used for miRNA hybridization. The starting material was 400 ng of total RNA of each sample. miRNA in the sample was labeled using the Flash Tag Biotin HSR RNA Labeling Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions.

We used a unique miRNA and 2 mRNA microarray batches in our experiments. Distribution of severe and mild patient samples within the batches was similar.

Statistical analysis for comparison of patient characteristics

The results of the statistical analyses are expressed as mean (SD) for quantitative variables and as valid percentage for groups using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U or chi-square tests (Fisher’s exact test when the expected frequencies were <5).

Data preprocessing and analysis of differentially expressed genes

First, a raw data quality control was performed before normalization in order to analyze sample quality, hybridization quality, signal comparability and biases, array correlation, and probe sets’ homogeneity.

Background correction and quantile normalization were performed for the raw array data using the oligo package (http://www.bioconductor.org/)26 and robust multi-array average (RMA package for R).27 For each sample, the expression values of all probes for a given gene were reduced to a single value by taking the average expression value. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed and a hierarchical clustering plot was made after normalization. Batch effects were analyzed using surrogate variable analysis (SVA package)28 and Combining Batches of Gene Expression Microarray Data (ComBat) functions.29

Before differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis, present probes without the corresponding gene symbols and expression intensities below the 3rd quartile value were removed for further statistical analysis. The Limma (Linear Models for Microarray Data) package30 was used to perform statistical testing of differential mRNA and miRNA expression between the 2 study groups. Differentially expressed mRNAs and miRNAs were defined as having a P-value of <0.05 with at least ±1.5-fold change (FC) (logFC ±0.58) between the groups. P-values adjusted for the false discovery rate (FDR) were also calculated.

DEGs annotation and pathway-enrichment analyses

DEGs were annotated identifying the beginning and the end of the chromosome as well as the gene symbol with the BioMart R package (http://www.biomart.org) and the Affymetrix annotation files.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Gene-ontology (GO) terms31 were enriched for DEGs using the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database. The major GO terms associated with biological processes was manually summarized based on gene-term enrichment provided for each functional group at a Fisher’s exact P-value of 0.05. The same statistical approach was used for KEGG analysis.

miRNA and mRNA data integration

Integration of miRNA DEGs and their target mRNA DEGs was performed using the multiMiR R package with the web server at http://multimir.ucdenver.edu. This is a comprehensive collection of predicted and validated miRNA–target interactions and their associations with diseases and drugs.32 All the analyses were performed using the R Studio (version 3.2.5).

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction validation

For all the samples, an independent analysis of EGR3 and EREG expression was performed by the quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) method. The levels of expression of selected genes were analyzed using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Madrid, Spain). The expression of the reference gene, hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (Life Technologies, #Hs02800695_m1), was used for normalization. Relative gene expression was calculated according to the Δ cycle threshold method using StepOne software. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05 as measured using the Student’s t-test.

Results

Blood PBMCs were isolated from 12 PiZZ patients: 6 with severe emphysema with a mean FEV1(%) of 44% (SD =6.7%) and 6 with mild disease, with FEV1(%) of 93% (SD =29%). Both study groups presented similar characteristics in terms of age, gender, exacerbations, comorbidities, and time from the last infusion. Severe patients were diagnosed at a younger age than mild patients (42.7 years [SD =6.4] vs 51.2 [SD =4.0], P=0.041) and all received inhaled corticosteroids (Table 1). Two patients from the severe group were current smokers and, therefore, did not receive replacement therapy. None of the patients in either group received systemic corticosteroids. The time from blood collection and processing in the laboratory was compared between groups without statistical differences.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| Variables | Mild emphysema N=6 |

Severe emphysema N=6 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at the time of the study | 61.7 (7.7) | 61.0 (10.5) | 0.937 |

| Age (years) at diagnosis | 51.2 (4) | 42.7 (6.4) | 0.041 |

| Gender | 0.999 | ||

| Male (%) | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Female (%) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Smoking history | 0.135 | ||

| Never (%) | 2 (33.3) | 0 | |

| Current (%) | 0 | 2 (33.3) | |

| Former (%) | 4 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) | |

| FEV1% | 93 (29) | 44 (6.7) | 0.002 |

| AAT blood levels (mg/dL) | 22 (5) | 27 (5.1) | 0.265 |

| Other comorbidities | |||

| Bronchiectasis | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0.098 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 0.125 |

| Inhaled respiratory treatments (%) | 4 (66.7) | 6 (100) | 0.225 |

| Beta2 agonists (%) | 4 (66.7) | 6 (100) | 0.065 |

| Inhaled corticosteroids (%) | 0 | 6 (100) | 0.025 |

| Replacement therapy (RT) (%) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 0.248 |

| Time from last RT infusion (days) | 15 | 15 | 0.999 |

| Time from blood collection to sample process (minutes) | 74.2 (49.6) | 68.3 (23.2) | 0.589 |

Notes: Data are expressed as mean (SD) or n (valid percentage). Bold values indicate p<0.05.

Abbreviations: AAT, alpha1-antitrypsin; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s.

mRNA analysis

Initially, the mRNA expression of 53,617 probe sets corresponding to 12 samples were included. Data were normalized and after filtering, a total of 10,143 probes were used for the following analysis. We found no batch effects according to the time of blood processing, study group, or gender (data not shown).

Normalized PCA results showed that the first axis explained 16% of the variance. Two samples corresponding to current smokers from the severe group presented a different gene expression profile according to the second axis that explained 10.5% of the variability. To avoid a potential gene expression bias, these 2 samples were removed from the following analyses. Finally, 10 AATD samples (4 from the severe and 6 from the mild disease groups) were included in the DEGs analysis.

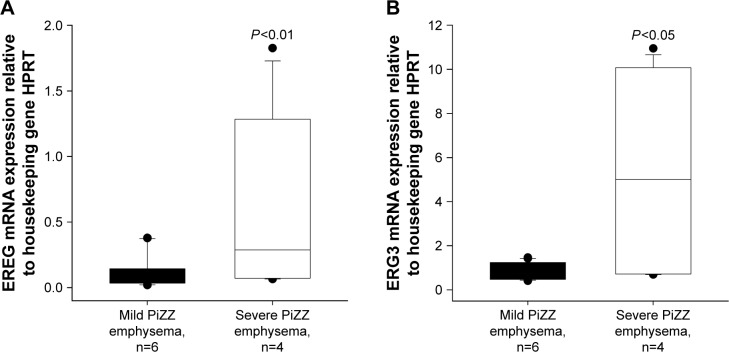

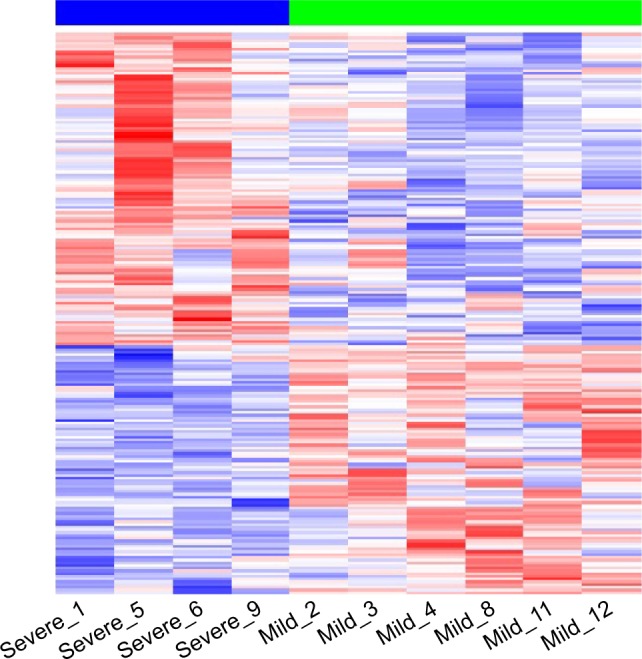

A total of 205 DEGs differed between severe and mild patients, of which 114 genes were upregulated and 91 downregulated in severe patients using non-adjusted P-value of <0.05 and FCs >±1.5 (logFC >±0.58) (Figure 1). FDR P-values were calculated, but no differences were found in gene expression between the 2 groups. Therefore, for all the following analyses, we used non-adjusted P-values.

Figure 1.

Differentially expressed genes in severe (blue line) vs mild (green line) patients.

Notes: Two-dimensional hierarchical clustering of the 10 samples according to the expression of 205 genes differentially expressed (by row) comparing severe (n=4) vs mild (n=6) patients (by column), with a P-value of <0.05 and fold changes (FC) >±1.5 (logFC >±0.58) using the Limma (Linear Models for Microarray Data) method. The functional classification of genes (color-coded) is shown. Red represents a high level of gene expression while blue represents a low level of expression.

The top dysregulated mRNAs are shown in Table 2. Upregulated genes with highest difference between the 2 groups (logFC >1) included HLA-DRB5, OLFM4, HBEGF, LFT, MMP8, CXCL8, SOCS3, CAMP, G0S2, CCL3L3, EREG, EGR3, NR4A2, JUP, and IL1B genes.

Table 2.

Top dysregulated mRNA comparisons in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from severe vs mild AATD emphysema patients

| Symbols | logFC | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | ||

| HLA-DRB5 | 2.46 | 0.025 |

| OLFM4 | 2.42 | 0.003 |

| HBEGF | 2.01 | 0.002 |

| LTF | 1.79 | 0.047 |

| MMP8 | 1.69 | 0.028 |

| CXCL8/IL-8 | 1.57 | 0.019 |

| SOCS3 | 1.56 | 0.000 |

| CAMP | 1.53 | 0.014 |

| G0S2 | 1.50 | 0.015 |

| CCL3L3/CCL3L1 | 1.38 | 0.001 |

| EREG | 1.37 | 0.018 |

| EGR3 | 1.31 | 0.004 |

| NR4A2 | 1.31 | 0.004 |

| OSM | 1.28 | 0.007 |

| CRISP3 | 1.24 | 0.043 |

| IL1B | 1.18 | 0.014 |

| JUP | 1.16 | 0.008 |

| PTGS2 | 1.11 | 0.038 |

| ID1 | 1.11 | 0.003 |

| CLEC5A | 1.10 | 0.003 |

| NR4A3 | 1.08 | 0.027 |

| SNAI1 | 1.00 | 0.003 |

| CD24 | 1.00 | 0.034 |

| Downregulated | ||

| XCL2 | −1.01 | 0.000 |

| PDK4 | −1.01 | 0.047 |

| RNU1–59P | −1.05 | 0.013 |

| ZNF208 | −1.12 | 0.000 |

Note: Table 2 shows different miRNAs using a P-value <0.05 and logFC >±1.

Abbreviations: AATD, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency; IL-8, interleukin-8; logFC, fold change logarithm; MMP, matrix metalloproteases protease; mRNA, messenger RNA.

These genes are involved in systemic and local inflammation, immunity, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and oncogenesis. We found that these groups of genes are enriched in different pathways such as the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) cascade pathway, the Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK) cascade, the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling pathway, the NOD-like receptor pathway, and the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway using GO and KEGG terms (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Gene ontology functional enrichment analysis of the DEGs between peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from severe vs mild AATD emphysema patients

| GO ID | Term | Odds ratio | P-value | DEGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | ||||

| 0043408 | Regulation of MAPK cascade | 4.8 | 9.03e-07 | ATF3, CCR1, HBEGF, DUSP1, EREG, ID1, IL1B, OSM, PARK2, TPD52L1, VEGFA, WNT7A, ARHGEF5, TRIB1, DACT1, AVPI1, CARD9, DUSP16, CCL3L3, CD24 |

| 0001525 | Angiogenesis | 4.68 | 4.41e-05 | ADM, ANPEP, EGR3, EREG, NR4A1, ID1, IL1B, CXCL8, MFGE8, PTGS2, VEGFA, WNT7A, PLXDC1 |

| 0001817 | Regulation of cytokine production | 4.17 | 7.3e-05 | CAMP, CD14, CLC, EREG, HLA-DRB5, IL1B, LTF, PTGS2, NR4A3, SOCS1, CLEC5A, CARD9, ATG9A, CD24 |

| 0007254 | JNK cascade | 6.17 | 9.2e-05 | IL1B, PARK2, TPD52L1, WNT7A, ARHGEF5, TRIB1, DACT1, CARD9 |

| 001937 | Cyclooxygenase pathway | 39.6 | 0.00012 | PTGDS, PTGS2, HPGDS |

| 0019221 | Cytokine-mediated signaling pathway | 3.55 | 0.00019 | CCR1, EGR1, EREG, CXCL2, HLA-DRB5, IL1B, CXCL8, OSM, PARK2, SOCS1, SOCS3, CCL3L3, CD24 |

| 0007249 | I-kappaB kinase/NFκB signaling | 4.51 | 0.00068 | CD14, IL1B, LTF, PARK2, PTGS2, OLFM4, PLK2, CARD9 |

| Downregulated | ||||

| 0043949 | Regulation of cAMP-mediated signaling | 25.7 | 0.00345 | CXCL10, PTGIR |

| 0035490 | Regulation of leukotriene production involved in inflammatory response | Inf | 0.00382 | SERPINE1 |

| 0055118 | Negative regulation of cardiac muscle contraction | 265 | 0.00762 | PDESA |

| 0007599 | Hemostasis | 3.75 | 0.0034 | A2M, SERPINE1, PTGIR, TFPI, PDE5A, P2RY12, HIST2H3D |

| 0006950 | Response to stress | 2.44 | 0.000726 | A2M, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRB1, IGFBP4, CXCL10, OAS3, SERPINE1, PDK4, PTGIR, XCL2, TFPI, HIST1H2BG, HIST1H2BF, HIST2H2BE, PDE5A, MTSS1, DCLRE1A, PDCD6, KLRG1, CRTAM, P2RY12, TNIP3, ZKSCAN3, DUSP19, HIST2H3D, GTF2H2C_2 |

Abbreviations: AATD, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; GO, gene ontology; JNK, jun amino-terminal kinases; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa B.

Table 4.

KEGG functional enrichment analysis of the DEGs between peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from severe vs mild AATD emphysema patients

| KEGG ID | Term | Odds ratio | P-value | DEGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 04640 | Hematopoietic cell lineage | 5.7 | 0.0014 | ANPEP, CD14, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DRB5, IL1B, CD24 |

| 00590 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | 5.9 | 0.00654 | PTGDS, PTGS2, HPGDS, PLA2G2C |

| 04621 | NOD-like receptor pathway | 5.9 | 0.00625 | CXCL2, IL1B, CXCL8, CARD9 |

| 04060 | Cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction | 2.89 | 0.00786 | CCR1, CXCL2, IL1B, CXCL8, OSM, XCL2, VEGFA, CCL3L3 |

| 05310 | Asthma | 8.29 | 0.00769 | HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DRB5 |

| 04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 2.69 | 0.036 | CCR1, CXCL2, CXCL8, CXCL10, XCL2, CCL3L3 |

| 04620 | Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 3.14 | 0.046 | CD14, IL1B, CXCL8, CXCL10 |

Abbreviations: AATD, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; NOD, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain.

miRNA DEGs analysis

The miRNA data were analyzed using the same pipeline as in mRNA data analysis. Initially, a quality control of 6,658 miRNA probes was performed and after filtering, 1,165 miRNA were included in the Limma analysis. A total of 28 miRNAs were found to be differently expressed in PBMCs from severe compared to mild AATD emphysema patients, with 20 miRNAs being upregulated and 8 being downregulated in severe patients (Table 5).

Table 5.

Dysregulated miRNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from severe compared with mild AATD emphysema patients

| miRNA ID | logFC | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | ||

| hsa-miR-708-5p | 2.46 | 0.009 |

| hsa-miR-4440 | 2.42 | 0.007 |

| hsa-miR-193b-3p | 2.01 | 0.036 |

| hsa-miR-3934-5p | 1.79 | 0.030 |

| hsa-miR-7846-3p | 1.69 | 0.003 |

| hsa-miR-873-5p | 1.57 | 0.008 |

| hsa-miR-27a-5p | 1.56 | 0.003 |

| hsa-miR-3064-3p | 1.53 | 0.018 |

| hsa-miR-146b-3p | 1.50 | 0.003 |

| hsa-miR-193b-5p | 1.38 | 0.009 |

| hsa-miR-873-3p | 1.37 | 0.035 |

| hsa-miR-146b-5p | 1.31 | 0.006 |

| hsa-miR-2278 | 1.31 | 0.021 |

| hsa-miR-1255a | 1.28 | 0.005 |

| hsa-miR-1225-5p | 1.24 | 0.035 |

| hsa-miR-135a-3p | 1.18 | 0.004 |

| hsa-miR-4723-5p | 1.16 | 0.037 |

| hsa-miR-874-3p | 1.11 | 0.008 |

| hsa-miR-365a-5p | 1.11 | 0.003 |

| hsa-miR-29b-1-5p | 1.10 | 0.003 |

| Downregulated | ||

| hsa-miR-543 | −1.00 | 0.018 |

| hsa-miR-139-3p | −1.00 | 0.013 |

| hsa-miR-485-3p | −1.02 | 0.049 |

| hsa-miR-335-5p | −1.01 | 0.047 |

| hsa-miR-139-5p | −1.01 | 0.040 |

| hsa-miR-486-3p | −1.05 | 0.049 |

| hsa-miR-185-3p | −1.12 | 0.020 |

| hsa-miR-328-3p | −1.20 | 0.025 |

Note: Table 5 shows different miRNAs using P-value <0.05 and logFC >±1.

Abbreviations: AATD, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency; logFC, fold change logarithm; miRNA, microRNA.

All the dysregulated miRNAs are shown in Table 5. Upregulated miRNA included hsa-miR-146b-3p, hsa-miR-146b-5p, hsa-miR-193b-3p, and hsa-miR-365a-5p, whereas downregulated miRNAs included hsa-miR-486-3p and hsa-miR-335-5p. The latter 2 have previously been reported to be related to respiratory diseases.

miRNA and mRNA interactions

As shown in Table 6, we identified 3 putative miRNA interacting targets between differentially expressed miRNAs and DEGs. Our analysis showed significant downregulation of hsa-miR-335-5p in severe patients, which was significantly linked to 12 upregulated transcripts, enriched in the cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, the MAPK/mk2 signaling cascade, the JNK cascade, and angiogenesis (Table 6).

Table 6.

miRNA–target interactions between differentially expressed miRNAs and mRNA in severe vs mild AATD emphysema patients

| Downregulated miRNA ID | Upregulated target gene | P-value | logFC |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-335-5p | EREG | 0.018 | 2.2 |

| OLFM4 | 0.003 | 1.4 | |

| NR4A2 | 0.004 | 1.2 | |

| JUP | 0.008 | 1.2 | |

| SLC2A3 | 0.012 | 0.97 | |

| NR4A1 | 0.018 | 0.97 | |

| NFIL3 | 0.001 | 0.84 | |

| ST14 | 0.002 | 0.73 | |

| TRIB1 | 0.015 | 0.70 | |

| RNF157 | 0.002 | 0.63 | |

| EGR3 | 0.004 | 0.60 | |

| MAFB | 0.018 | 0.60 | |

| Upregulated miRNA ID | Downregulated target gene | ||

| hsa-miR-874-3p | HIST1H4H | 0.001 | −1.2 |

| hsa-miR-193b-3p | HIST2H3D | 0.002 | −0.6 |

Notes: Integration of validated and predicted interactions between miRNAs and their target genes using multiMiR R package. Comparisons were performed using a P-value <0.05 and FC >±1.5 (logFC >±0.58).

Abbreviations: AATD, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency; logFC, fold change logarithm; miRNA, microRNA.

qRT-PCR validation of DEGs

We randomly selected EREG and EGR3 genes to be verified by qRT-PCR. We have chosen these 2 genes with lower FCs, hoping to reproduce our findings by using an independent method. In accordance with microarray data, the expression of both genes was significantly higher in PBMCs from severe than from mild AATD emphysema patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Note: Validation of EREG (A) and EGR3 (B) expression compared with housekeeping gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT).

Abbreviation: mRNA, messenger RNA.

Discussion

One of the important issues in developing biomarkers for clinical purposes is the selection of appropriate cells or tissues from which candidates can be identified. Because of the systemic nature of COPD/emphysema33 and because of unique properties of AAT protein,34 we hypothesized that genome-wide expression profiling of peripheral blood cells may be used to identify signatures of AATD-related emphysema phenotypes. PBMCs are attractive candidates because they are easy to obtain and simple to prepare. Therefore, here we performed the gene expression profiling of PBMCs collected from severe and mild emphysema patients with PiZZ AATD. Our objective was to identify putative differences in mRNA and miRNAs expression that might be associated with disease severity. The microarray analysis of PBMCs isolated from 10 emphysema patients with PiZZ AATD revealed that cells from patients with severe disease presented 205 differentially expressed mRNAs (114 upregulated and 91 downregulated) and 28 miRNAs (20 upregulated and 8 downregulated) compared to those from patients with mild disease. Moreover, we found an interaction between downregulated hsa-miR-335-5p and 12 upregulated target gene mRNAs. These latter genes are related to the cytokine-mediated signaling pathway, the MAPK/mk2 signaling cascade, the JNK cascade, and angiogenesis. It is important to remark that all our patients were clinically stable and took their usual respiratory treatment at inclusion in the study.

In the cells of severe patients, we found a higher expression of the EREG, EGR3, and TRIB1 genes, which are involved in inflammatory response-related signal transduction pathways including MAPK.35 EGR3 is a zinc finger transcription factor, an immediate-early response protein activated by cellular stressors.36 As a major transcription factor, EGR3 alters the expression of several target genes, including repair enzyme systems, angiogenic factors, cytokines (interleukin-8 [IL-8] and tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNFα]), apoptotic factors (Fas), cell cycle factors (p21 and p53), metabolic factors, and matrix metalloproteases proteases (MMPs). In parallel to EGR3, we also found a higher expression of cytokines (IL1B, CCL3L3, and CXCL8). Hence, there may be a direct link between EGR3 and cytokine expression, which has already been validated as a target gene in respiratory inflammation and different cancers.37

The activation of members of the MAPK family triggers the activation of transcription factors such as the nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) subunit 1.38 Activation of NFκB eventually results in the expression of a battery of genes that regulate inflammatory, apoptotic, and proliferative responses associated with the pathogenesis of emphysema.39 Previous studies have shown the activation of NFκB in the bronchial biopsies and inflammatory cells of non-AATD COPD patients.40 Gene expression profiling studies have revealed that inflammatory cytokine- and chemokine-related genes (ie, fractalkine/CX3CL1) are significantly increased in stable non-AATD-COPD patients, becoming more pronounced during COPD exacerbations.21,41

Transcripts involved in the JNK cascade pathway were also upregulated in severe compared to mild COPD patients. Recent data by Pastore et al42 revealed that JNK and c-JUN play a role in SERPINA1 gene transcriptional upregulation in AATD-related liver disease. To date, however, there are no studies investigating the impact of JNK on the pathogenesis of AATD.

Changes in miRNA expression are associated with the development and progression of cancer, and cardiovascular and inflammatory pulmonary diseases.13,43 We found 8 miRNAs to be downregulated in PBMCs from severe patients, including hsa-miR-486-3p and hsa-miR-335-5p, which have previously been reported to be related to respiratory diseases. Downregulation of hsa-miR-335-5p involves the activation of pathways related to inflammation and angiogenesis. Therefore, our analysis suggests a potential novel link between decreased miR-335-5p expression and the severity of AATD-related emphysema. The integrative analysis revealed that miR-335-5p interacts with other miRNAs previously described in emphysema. For example, high expression of hsa-miR 146-5p in cells from severe patients supports the findings by Ezzie et al,18 who stated that miR-146a expression is higher in lung tissue from patients with COPD than in non-COPD smokers. In contrast, Sato et al44 reported reduced expression of miR-146a in cultured fibroblasts from COPD subjects. miR-146a was downregulated in sputum of patients with COPD and smokers compared with never-smokers, and in smokers with COPD in comparison to smokers without COPD.45 Overall, recent studies support the hypothesis that miR-146a and miR-146b play a role in the regulation of inflammatory pulmonary disorders.46

The results of the present study provide additional support for the role of miRNAs in COPD and improve the understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the expression of peripheral inflammatory cells in patients with severe and mild AATD-related emphysema.

Limitations

We found significant differences in the expression patterns of genes between severe and mild emphysema patients with PiZZ AATD. However, the results from this small pilot study must be complemented by the inclusion of a control group of patients with non-AATD–related COPD. A control group would help to clarify whether the activation of pathways related to inflammation, immune response, and angiogenesis are the cause or the effect of more progressed emphysema. Golpon et al35 found some degree of shared gene profiles between “usual” non-AATD–related emphysema and AATD-related emphysema. These authors observed statistically significant differences in the modulation of genes associated with protein and energy metabolism and immune function, which allow differentiation between these 2 emphysema types at the lung tissue level. We are aware that differences in the genetic signatures of PBMCs isolated from severe vs mild PiZZ AATD patients need to be validated in a larger study population.

In our analysis, 12 samples were initially included, but 2 current smokers were excluded from the patient group with severe AATD emphysema. According to the quality control analysis, the gene expression profile of these individuals was markedly different compared with the other samples. Cigarette smoke is a complex mixture of >4,000 chemical compounds that can induce a variety of biological responses, including oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation, among others.47 In general, most studies report a global downregulation and upregulation of miRNA and mRNA abundance in response to cigarette smoking.18,48 We plan to perform a separate study to analyze the gene expression profiles in PBMCs isolated from smokers with severe and mild COPD.

The cellular gene expression pattern may be influenced by multiple factors, such as patient age, gender, genetic background, and treatment. Replacement therapy could have influenced gene expression. Some studies have suggested that replacement therapy may reduce airway inflammation.49–51 However, Olfert et al52 found that replacement therapy reduces the concentration of TNF-alpha, but has no effect on IL-6, IL1B, or C-reactive protein. In our study, 4 severe and 2 mild emphysema AATD patients received augmentation therapy every 15 days. To minimize the potential effect of replacement therapy, blood samples were taken just before the patients received the next infusion. However, it would be important to include PBMCs from patients who have never received augmentation therapy.

Conclusion

The findings of this analysis provide novel information about the different gene profile of PBMCs isolated from patients with severe and mild emphysema with PiZZ AATD. We specifically identified downregulated miRNA (hsa-miR-335) in severe AATD patients. The hsa-miR-335-5p regulates important transcription factors involved in the activation of pathways directly related to inflammation and angiogenesis and could play an important role in the pathogenesis of this rare condition. Nevertheless, further analyses are needed to validate these results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Biobank at the Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain. This study was funded by a grant from the Fundació Catalana de Pneumologia (FUCAP) year 2017 and by an unrestricted grant from the Catalan Center of Excellence for the management of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in the Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona) supported by Grifols (Barcelona, Spain).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lomas DA, Mahadeva R. Alpha-1-antitrypsin polymerization and the serpinopathies: pathobiology and prospects for therapy. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(11):1585–1590. doi: 10.1172/JCI16782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeMeo DL, Silverman EK. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. 2: genetic aspects of alpha(1)-antitrypsin deficiency: phenotypes and genetic modifiers of emphysema risk. Thorax. 2004;59(3):259–264. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.006502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco I, Bueno P, Diego I, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin Pi*Z gene frequency and Pi*ZZ genotype numbers worldwide: an update. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:561–569. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S125389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tirado-Conde G, Lara B, Casas F, et al. Factors associated with the evolution of lung function in patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in the Spanish registry. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47(10):495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanash HA, Nilsson PM, Nilsson JA, Pituilainen E. Clinical course and prognosis of never smokers with severe AATD (PiZ) Thorax. 2008;63(12):1091–1095. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.095497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency Registry Study Group Survival and FEV1 decline in individuals with severe deficiency of alpha-1-antitrypsin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(1):49–59. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9712017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seersholm N, Kok-Jensen A, Dirksen A. Decline in FEV1 among patients with severe hereditary ATAD type PiZ. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(6 Pt 1):1922–1925. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Hong YQ, Meng ZL. Bioinformatics analysis of molecular mechanisms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18(23):3557–3563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei L, Xu D, Qian Y, et al. Comprehensive analysis of gene-expression profile in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1103–1109. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S68570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faner R, Cruz T, Casserras T, et al. Network analysis of lung transcriptomics reveals a distinct B-Cell signature in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(11):1242–1253. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1311OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angulo M, Lecuona E, Sznajder JI. Role of microRNAs in lung disease. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48(9):325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nana-Sinkam SP, Hunter MG, Nuovo GJ, et al. Integrating the MicroR-Nome into the study of lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(1):4–10. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1042PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomankova T, Petrek M, Kriegova E. Involvement of microRNAs in physiological and pathological processes in the lung. Respir Res. 2010;11:159. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagdin T, Lavender P. MicroRNAs in lung diseases. Thorax. 2012;67:183–184. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raponi M, Dossey L, Jatkoe T, et al. MicroRNA classifiers for predicting prognosis of squamous cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5776–5783. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ezzie ME, Crawford M, Cho JH, et al. Gene expression networks in COPD: microRNA and mRNA regulation. Thorax. 2012;67(2):122–131. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbs BD, Hersh CP. Integrative genomics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;452(2):276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen ZH, Kim HP, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Identifying targets for COPD treatment through gene expression analyses. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3(3):359–370. doi: 10.2147/copd.s1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X, Sun X, Chen C, Bai C, Wang X. Dynamic gene expressions of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a preliminary study. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):508. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0508-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Statement: Standards for the diagnosis and management of individuals with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(7):818–900. doi: 10.1164/rccm.168.7.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal N, Koepke J, Matamala N, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin regulates transcriptional levels of serine proteases in blood mononuclear cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(9):1065–1067. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2062LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al. Spanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC) 2017. Pharmacological treatment of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(6):324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casas F, Blanco I, Martínez MT, et al. Indications for active case searches and intravenous alpha-1 antitrypsin treatment for patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an update. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(4):185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2363–2367. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4(2):249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leek JT, Johnson WE, Parker HS, et al. sva: Surrogate Variable Analysis. R package version 3.20.0. 2016. [Accessed October 18, 2017]. Available from: https://bioconductor.riken.jp/packages/3.0/bioc/html/sva.html.

- 29.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8(1):118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. the gene ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ru Y, Kechris KJ, Tabakoff B, et al. The multiMiR R package and database: integration of microRNA-target interactions along with their disease and drug associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(17):e133. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agusti AG, Noguera A, Sauleda J, Sala E, Pons J, Busquets X. Systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(2):347–360. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00405703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janciauskiene SM, Bals R, Koczulla R, Vogelmeier C, Köhnlein T, Welte T. The discovery of α1-antitrypsin and its role in health and disease. Respir Med. 2011;105(8):1129–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golpon HA, Coldren CD, Zamora MR, et al. Emphysema lung tissue gene expression profiling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31(6):595–600. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0008OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SL, Sadovsky Y, Swirnoff AH, et al. Luteinizing hormone deficiency and female infertility in mice lacking the transcription factor NGFI-A (Egr-1) Science. 1996;273:1219–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baron VT, Pio R, Jia Z, Mercola D. Early growth response 3 regulates genes of inflammation and directly activates IL6 and IL8 expression in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(4):755–764. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Underwood DC, Osborn RR, Bochnowicz S, et al. SB 239063, a p38 MAPK inhibitor, reduces neutrophilia, inflammatory cytokines, MMP-9, and fibrosis in lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279(5):L895–L902. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.5.L895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298(5600):1911–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1072682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuliga M. NF-KappaB in chronic inflammatory airway disease. Biomolecules. 2015;5(3):1266–1283. doi: 10.3390/biom5031266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto C, Yoneda T, Yoshikawa M, et al. Airway inflammation in COPD assessed by sputum levels of interleukin-8. Chest. 1997;112(2):505–510. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.2.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pastore N, Attanasio S, Granese B, et al. Activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway aggravates proteotoxicity of hepatic mutant Z alpha1-antitrypsin. Hepatology. 2017;65(6):1865–1874. doi: 10.1002/hep.29035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang JT, Wang J, Srivastava V, Sen S, Liu SM. MicroRNA machinery genes as novel biomarkers for cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:113. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato T, Liu X, Nelson A, et al. Reduced MiR-146a increases prostaglandin E2 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease fibroblasts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(8):1020–1029. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0055OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Pottelberge GR, Mestdagh P, Bracke KR, et al. MicroRNA expression in induced sputum of smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(7):898–906. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0304OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomankova T, Petrek M, Kriegova E. Involvement of microRNAs in physiological and pathological processes in the lung. Respir Res. 2010;11:159. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moretto N, Volpi G, Pastore F, Facchinetti F. Acrolein effects in pulmonary cells: relevance to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2012;1259:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graff JW, Powers LS, Dickson AM, et al. Cigarette smoking decreases global microRNA expression in human alveolar macrophages. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e44066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, He Y, Abraham B, et al. Cystosolic, autocrine alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor (A1P1) inhibits caspase-1 blocks IL-1 beta dependent cytokine release in monocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e51078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stockley RA, Bayley DL, Unsal I, Dowson LJ. The effect of augmentation therapy on bronchial inflammation in alpha1 antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(11):1494–1498. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schimid ST, Koepke J, Dresel M, et al. The effects of weekly augmentation therapy in patients with PiZZ alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:687–696. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S34560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olfert IM, Malek MH, Eagan TM, Wagner H, Wagner PD. Inflammatory cytokine response to exercise in alpha-1-antitrypsin deficient COPD patients ‘on’ or ‘off’ augmentation therapy. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]