Abstract

Objective:

There is a need for the routine monitoring of treated attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for timely policy making. The objective is to report and assess over a decade the prevalence and incidence of diagnosed ADHD in Canada.

Methods:

Administrative linked patient data from the provinces of Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia were obtained from the same sources as the Canadian Chronic Diseases Surveillance Systems to assess the prevalence and incidence of a primary physician diagnosis of ADHD (ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes: 314, F90.x) for consultations in outpatient and inpatient settings (Med-Echo in Quebec, the Canadian Institute of Health Information Discharge Abstract Database in the 3 other provinces, plus the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System). Dates of service, diagnosis, and physician specialty were retained. The estimates were presented in yearly brackets between 1999-2000 and 2011-2012 by age and sex groups.

Results:

The prevalence of ADHD between 1999 and 2012 increased in all provinces and for all groups. The prevalence was approximately 3 times higher in boys than in girls, and the highest prevalence was observed in the 10- to 14-year age group. The incidence increased between 1999 and 2012 in Manitoba, Quebec, and Nova Scotia but remained stable in Ontario. Incident cases were more frequently diagnosed by general practitioners followed by either psychiatrists or paediatricians depending on the province.

Conclusion:

The prevalence and incidence of diagnosed ADHD did not increase similarly across all provinces in Canada between 1999 and 2012. Over half of cases were diagnosed by a general practitioner.

Keywords: ADHD, surveillance, diagnosis, temporal trends, data linkage

Abstract

Objectif:

Il existe un besoin de surveillance courante du trouble de déficit de l’attention avec hyperactivité (TDAH) traité pour l’élaboration ponctuelle des politiques. L’objectif est de signaler et d’évaluer sur une décennie la prévalence et l’incidence du TDAH traité au Canada.

Méthodes:

Les données administratives couplées des patients des provinces du Manitoba, de l’Ontario, du Québec et de la Nouvelle-Écosse ont été obtenues des mêmes sources que le Système national de surveillance des maladies chroniques, afin d’évaluer la prévalence et l’incidence d’un diagnostic de TDAH par un médecin des soins de première ligne (codes de la CIM-9 et de la CIM-10: 314, F90.x) pour des consultations en contexte ambulatoire et en milieu hospitalier (Med-Écho au Québec, la Base de données sur les congés des patients de l’Institut canadien d’information sur la santé dans les 3 autres provinces, plus le Système d’information ontarien sur la santé mentale). Les données sur les services, le diagnostic, et la spécialité du médecin ont été retenues. Les estimations ont été présentées en tranches annuelles entre 1999-2000 et 2011-2012 selon les groupes d’âge et de sexe.

Résultats:

La prévalence du TDAH entre 1999 et 2012 a augmenté dans toutes les provinces et pour tous les groupes. La prévalence était approximativement 3 fois plus élevée chez les garçons que chez les filles, et la prévalence la plus élevée s’observait dans le groupe des 10 à 14 ans. L’incidence s’est accrue entre 1999 et 2012 au Manitoba, au Québec et en Nouvelle-Écosse mais est demeurée stable en Ontario. Les cas incidents étaient plus fréquemment diagnostiqués par des omnipraticiens, suivis des psychiatres ou des pédiatres, selon la province.

Conclusion:

La prévalence et l’incidence du TDAH diagnostiqué n’ont pas augmenté de manière semblable dans toutes les provinces du Canada entre 1999 et 2012. Plus de la moitié des cas a été diagnostiquée par un omnipraticien.

Introduction

There is currently great controversy surrounding the pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in Canada. This has been highlighted by black box warnings, by the government of Canada, relating to the cardiovascular safety and risk of sudden unexplained death in children,1 psychological and physical dependency in people with substance and alcohol problems, and risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours2 of these medications, underlining the importance of monitoring the prevalence and incidence of treatment. There is a growing interest in the potential of big data as monitoring tools for disease surveillance as well as to inform health policy.3,4 Until recently, variability in data coding has limited comparisons across jurisdictions,3 although the Public Health Agency of Canada’s (PHAC’s) Chronic Diseases Surveillance System (CDSS) has shown it is possible to establish standardised case definitions for psychiatric disorders.5,6

ADHD is a common neurodevelopmental disorder in children and adults characterised by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.7 In a systematic review, Polanczyk et al.8 reported, with important regional variations, a worldwide pooled estimate reaching 5.3%. In the United States, the prevalence of parent-reported child ADHD was as high as 11.0% in those aged between 4 and 17 years.9 In Canada, data from the National Longitudinal Survey on Children and Youth in children aged 3 to 9 years showed a prevalence of ADHD reaching 2.6% in 2006-2007.10 Data from the Canadian Community Health Survey showed a prevalence of ADHD reaching 2.7% in adults aged 20 years and older.11 In reviewing electronic primary medical records of family physicians in Ontario, Hauck et al.12 reported a prevalence of ADHD reaching 5.4% in patients aged 1 to 24 years. An earlier study in Manitoba, based on administrative physician and prescription claims data in 1995-1996, reported a prevalence of childhood ADHD reaching 1.5%.13 Follow-up studies have shown that the majority (60%-85%) of children with ADHD continue to meet criteria for the disorder during their teenage years.14,15 A meta-analysis reported that 65% of persons with childhood ADHD remained symptomatic in early adulthood, with 15% having significant limitations.16

The treatment prevalence of ADHD varies both within and between countries, as well as over time.8,17 In Canada, data from the IMS Brogan databases between 2005 and 2009 showed an increase of 36% in the prescription of psychostimulants in children.18 Unfortunately, population-level data on medication use in Canada are not easily linked to specific diagnoses. In the study by Brault and Lacourse,10 the prevalence of prescribed medications for ADHD in 2006-2007 was estimated to reach 1.1%. The chart review by Hauck et al.12 showed that 70% of youth with ADHD were prescribed either a stimulant or nonstimulant. Of these youth with ADHD, 20%, 12%, and 5% were prescribed an antidepressant, an antipsychotic, and a benzodiazepine, respectively. In the study by Brownell and Yogendran,13 0.9% of Manitoba children were prescribed a stimulant, of whom 80% also had a physician diagnosis of ADHD. In Australia, the number of prescriptions for psychostimulants is 75 times higher in the area with the highest rate compared to the area with the lowest rate.19 These differences may partly be due to variations in clinical practice guidelines between countries and jurisdictions as well as methodological definitions. These differences may also in part be due to the validity of the diagnostic codes used and differences in data analysis, underlining the necessity that all studies employing routinely collected data use the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely-Collected Health Data (RECORD) statement.4,20 However, given the wide range, the absence of a standardised recording system is unlikely to be the sole explanation.

For timely health system evaluation, routine epidemiologic data need to be available to inform health policies and resource allocation equitably to meet the needs of Canadian children. As underlined by Visser et al.,21 describing temporal changes in the epidemiology of ADHD from available population-based data sets can inform on population service use and needs. The main objective of this article was to report the yearly prevalence and incidence (1999-2012) of physician-diagnosed ADHD in 4 Canadian provinces (Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia). We specifically investigated whether estimates would be comparable across the 4 provinces and groups by age and sex. A secondary objective was to report the diagnosed incidence of ADHD by physician specialty (paediatrician, family physician/general practitioner, and psychiatrist). We used Canadian CDSS databases, including provincial hospital and physician claims data, and followed the guidelines from the RECORD statement.20

Methods

Study Population and Provincial Data Sources

The study population consisted of children (1-17 years) and young adults (18-24 years), who were residents of each province and eligible for coverage under the appropriate provincial health plan and who received a primary diagnosis of a mental disorder between 1999 and 2012. In each province, we captured data from physician billings data, including dates of service, diagnosis, and specialty of the physician seen. Data on inpatient health service use came from hospital discharge data (Med-Echo in Quebec, the Canadian Institute of Health Information [CIHI] Discharge Abstract Database in the 3 other provinces, plus the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System [OMHRS] in Ontario), including separation and admission dates and diagnoses. Diagnostic information in Med-Echo and CIHI-DAD was coded using ICD-9 prior to 2006 and 2002, respectively, and ICD-10 afterwards.

Provinces in Canada have a universal health care and physician fee-for-service system. With the exception of services rendered by salaried physicians, almost all contacts between residents and physicians are captured in provincial physician file claims for reimbursement databases. In Canada, although 11% of physicians are salaried, they report through shadow billing their consultations and medical acts provided, which represents 10% of total fee for service.22

Case Definition

To be considered as having a diagnosis of ADHD, individuals must have had at least 1 visit or hospitalisation within a given year with the following primary diagnoses: 314 for ICD-9 or the equivalent ICD-10 code (F90.x). This definition did not include secondary diagnoses or health contacts within schools. Physician diagnoses could be made by general practitioners, paediatricians, psychiatrists, or other specialists.

A case would be defined as incident and recorded once during the study period to avoid double counting. For instance, the same case diagnosed during the fiscal years 2003-2004 and 2005-2006 would be identified as an incident case in 2003-2004 and as a prevalent case in 2005-2006. Data were available from April 1, 1995, for the provinces of Ontario, Manitoba, and Nova Scotia and January 1, 1996, for Quebec. This observation period was used to distinguish between incident and prevalent cases in 1999-2000. Age was assigned at the end of each fiscal year, March 31.

Analyses

Incidence and prevalence were calculated yearly for fiscal years between 1999 and 2012 for Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec and 2011 for Nova Scotia. A fiscal year started April 1 and ended on March 31. The annual prevalence of ADHD referred to the proportion of persons aged 24 years or younger who had received a primary diagnosis of ADHD in a given year. The annual incidence of ADHD referred to the proportion of new cases of ADHD diagnosed during the year who had never previously received a diagnosis of ADHD. Rates were standardised according to the Canadian population age structure in 1991 considering the following age bands: 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, 15-17, and 18-24. Estimates are presented with their 95% confidence interval (CI). Nonoverlapping 95% CIs were interpreted as estimates being statistically different.

Ethics

The project was approved by the Montreal Mental Health University Institute. In all provinces, the data repository agency had clearance from the provincial data privacy agency to use appropriate case definitions for surveillance and research purposes, providing only aggregated data with rules of disclosure similar to those used by the Canadian CDSS of the PHAC.

Results

The overall annual age-standardised prevalence of ADHD per 1000 population for those aged between 1 and 17 years increased from 1999 to 2011-2012 in Nova Scotia (22.0 [95% CI, 21.4-22.7] to 37.9 [95% CI, 37.0-38.8]), Manitoba (15.4 [95% CI, 15.0-15.9] to 27.5 [95% CI, 26.9-28.1]), Quebec (10.9 [95% CI, 10.7-11.0] to 37.6 [95% CI, 37.3-37.9]), and Ontario (10.6 [95% CI, 10.4-10.7) and 11.0 [95% CI, 10.9-11.13]). The prevalence of ADHD per 1000 population for those aged 18 to 24 years also increased during the same period in Nova Scotia (4.7 [95% CI, 4.3-5.2] to 17.4 [95% CI, 15.5-18.2]), Manitoba (1.8 [95% CI, 1.6-2.1] to 8.1 [95% CI, 7.6-8.6]), Quebec (0.5 [95% CI, 0.4-0.5] to 7.2 [95% CI, 7.0-7.4]), and Ontario (1.5 [95% CI, 1.4-1.6) and 5.3 [95% CI, 5.1-5.4]).

When looking at the annual prevalence estimates by province, the data showed the following. In Manitoba, the prevalence increased in 2001-2002, 2002-2003, 2006-2007, 2007-2008, and 2010-2011 as opposed to the previous fiscal year. In Nova Scotia, there was a significant increase in prevalence each year between 2000-2001 to 2005-2006 and 2009-2010 and 2010-2011. In Ontario, there was an increase in prevalence each year between 2002-2003 and 2005-2006 and then a decrease each year between 2006-2007 and 2009-2010, with rates stabilising thereafter. In Quebec, the data showed a significant increase in prevalence each year reported from 1999-2000 to 2011-2012. When stratified by sex, prevalence estimates were significantly higher in boys than girls in the 4 provinces in 1999 to 2011 (Table 1). The data also showed that the prevalence of ADHD was highest in the 5- to 9-year-old and 10- to 14-year-old age groups (Figure 1) across all years (1999-2012).

Table 1.

Age-Standardised Prevalence (per 1000) of Diagnosed Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder by Sex.

| 1999-2000 (95% Confidence Interval) | 2011-2012 (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| Manitoba | ||

| Male | 24.1 (23.3-24.7) | 41.0 (40.0-42.1) |

| Female | 6.3 (5.9-6.7) | 13.20 (12.59-13.8) |

| Nova Scotia | ||

| Male | 34.6 (33.5-35.8) | 55.0 (53.5-56.6) |

| Female | 8.8 (8.2-9.4) | 19.4 (18.5-20.4) |

| Ontario | ||

| Male | 16.4 (16.2-16.6) | 16.0 (15.8-16.2) |

| Female | 4.4 (4.3-4.5) | 5.8 (5.6-5.9) |

| Quebec | ||

| Male | 16.9 (16.6-17.2) | 52.4 (51.9-52.9) |

| Female | 4.6 (4.4-4.7) | 22.2 (21.8-22.5) |

Figure 1.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder prevalence by year, age group, and province.

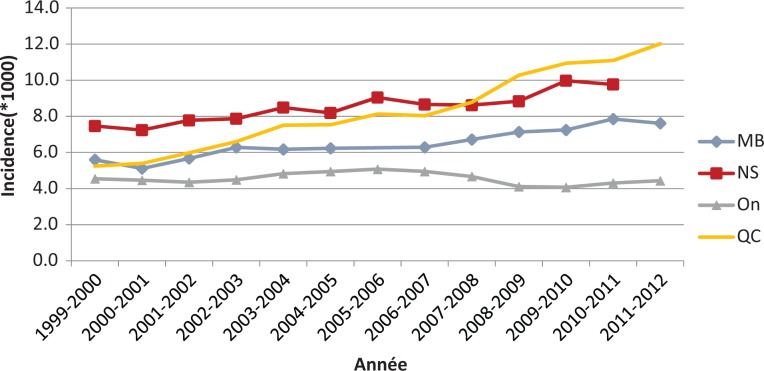

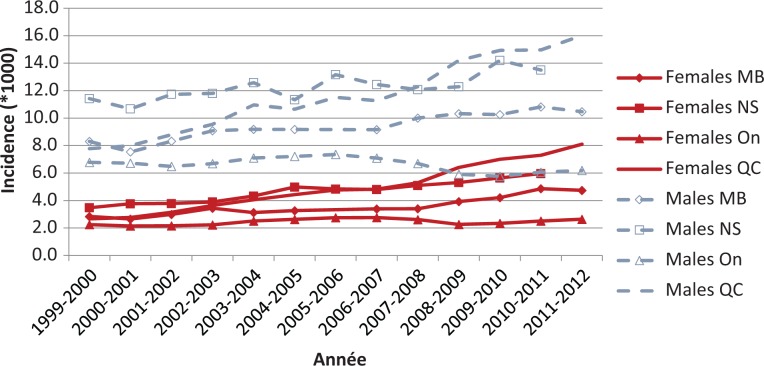

The overall annual incidence per 1000 of ADHD by reporting province in those aged 1 to 17 years is presented in Figure 2. Between 1999 and 2012, the results showed an increasing trend of ADHD diagnosis in the provinces of Nova Scotia (7.5 [95% CI, 7.1-7.9] to 9.8 [95% CI, 9.3-10.3]), Manitoba (5.6 [95% CI, 5.3-5.9] to 7.6 [95% CI, 7.3-8.0]), and Quebec (5.2 [95% CI, 5.1-5.4] to 12.0 [95% CI, 11.8-12.2]). This was not observed in Ontario, where the annual incidence per 1000 was 4.6 (95% CI, 4.5-4.6) and 4.4 (95% CI, 4.4-4.5). The annual incidence of ADHD (Figure 3) was higher in boys than girls in all reporting provinces and showed patterns similar to those observed for the annual prevalence. Furthermore, the incidence of diagnosed ADHD was highest in those in the 5- to 9-year and 10- to 14-year age groups across all years (1999-2012) and in every province. Table 2 compares age groups by province in 1999-2000 and 2011-2012.

Figure 2.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder incidence by year and province. MB, Manitoba; NS, Nova Scotia; On, Ontario; QC, Quebec.

Figure 3.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder incidence by year, sex, and province.

Table 2.

Incident Rates per 1000 Population by Age Group by Province.

| 1999-2000 (95% Confidence Interval) | 2011-2012 (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| Manitoba | ||

| 1-4 | 3.3 (2.9-3.8) | 4.3 (3.8-4.8) |

| 5-9 | 10.3 (9.6-11.0) | 14.0 (13.2-14.9) |

| 10-14 | 6.2 (5.7-6.8) | 7.4 (6.8-8.1) |

| 15-17 | 2.2 (1.8-2.7) | 4.0 (3.5-4.6) |

| 18-24 | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 1.8 (1.6-2.0) |

| Nova Scotia | ||

| 1-4 | 3.2 (2.7-3.7) | 4.95 (4.3-5.7) |

| 5-9 | 13.4 (12.5-14.4) | 19.6 (18.3-20.9) |

| 10-14 | 8.1 (7.4-8.8) | 8.4 (7.6-9.2) |

| 15-17 | 4.4 (3.7-5.1) | 5.2 (4.4-6.0) |

| 18-24 | 1.9 (1.6-2.2) | 4.1 (3.7-4.6) |

| Ontario | ||

| 1-4 | 1.8 (1.7-1.9) | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) |

| 5-9 | 8.3 (8.1-8.5) | 7.8 (7.6-8.0) |

| 10-14 | 5.1 (4.9-5.2) | 4.76 (4.6-4.9) |

| 15-17 | 2.4 (2.3-2.6) | 3.15 (3.0-3.3) |

| 18-24 | 0.6 (0.5-0.6) | 1.93 (1.9-2.0) |

| Quebec | ||

| 1-4 | 2.5 (2.3-2.6) | 2.85 (2.7-3.0) |

| 5-9 | 10.8 (10.5-11.1) | 21.1 (20.6-21.5) |

| 10-14 | 5.7 (5.5-6.0) | 15.0 (14.6-15.4) |

| 15-17 | 1.4 (1.3-1.5) | 7.3 (6.9-7.6) |

| 18-24 | 0.3 (0.2-0.3) | 2.5 (2.4-2.7) |

The data also showed some provincial variations when looking at physician specialty in incident diagnoses. In Nova Scotia, incident diagnoses were primarily made by general practitioners, followed by paediatricians and then psychiatrists in 1999-2000 (65%, 32%, 3%) and 2011-2012 (69%, 27%, 3%). For Ontario and Quebec, the patterns shifted over time. In Ontario, the 1999-2000 diagnoses were primarily by paediatricians (47%) and general practitioners (36%), followed by psychiatrists (17%) and other specialists (<1%), but in 2011-2012, they were made by general practitioners (52%), psychiatrists (24%), paediatricians (23%), and other specialists (<1%). In Quebec, the 1999-2000 diagnoses were primarily by paediatricians (49%), general practitioners (26%), and psychiatrists (14%), followed by other specialists (11%). In 2011-2012, the primary sources of incident ADHD diagnoses were general practitioners (46%) and paediatricians (43%), followed by psychiatrists (8%) and other specialists (3%). Unfortunately, data were not available for Manitoba.

Discussion

In the present study, the latest reported past-year prevalence of diagnosed ADHD for those aged between 1 and 17 years was significantly higher in Nova Scotia (3.8%) and Quebec (3.8%) than it was in Manitoba (2.8%) and Ontario (1.1%). When looking at those aged between 18 and 24 years, the past-year prevalence of ADHD in our study was highest in Nova Scotia (1.7%), followed by Manitoba (0.8%), Quebec (0.7%), and Ontario (0.5%).

Although the prevalence of diagnosed ADHD increased between 1999 and 2012 in all provinces studied, these estimates are lower than earlier population-based child mental health surveys. In their review of 6 child mental health population surveys, around the 1990s in Ontario, Quebec, the United Kingdom, and the United States, Waddell et al.23 reported a prevalence of ADHD averaging 4.8% (95% CI, 2.7-7.3). The study by Brault and Lacourse10 on young children reported the prevalence of a diagnosis and prescribed medication for ADHD to be 2.6% and 2.1% in 2000-2001 and 1.7% and 1.1% in 2006-2007. In Ontario, the chart review by Hauck et al.12 showed a prevalence of 5.6% when the presence of ADHD was based on either a physician diagnosis or information sent by the school. Slightly closer to our results are those reported by Brownell and Yogendran,13 who calculated the prevalence of ADHD at 1.5% when using both physician and prescriptions administrative claims files in Manitoba in 1995-1996. Also similar to our results by age and sex group, the Manitoba data13 showed higher prevalence estimates, per 100 population, in those aged 4 to 6 years (1.7; 99% CI, 1.5-1.8), 7 to 9 years (2.9; 99% CI, 2.7-3.1), and 10 to 13 years (22.4; 99% CI, 2.1-2.4) than children aged 0 to 3 years (0.5; 99% CI, 0.4-3.1) and 14 years and older (0.8; 99% CI, 0.7-0.9). Higher prevalence estimates were also reported for boys (2.4; 99% CI, 2.3-2.5) than girls (0.6; 99% CI, 0.5-0.7) across all age groups.13

The increase in prevalence of ADHD observed in this study between 1999 and 2012 was not similar in all provinces studied. Reports in the United States have also found similar increases in treated ADHD reaching over 22% over the past decade9 with state variations (lowest in the western regions) and gender differences (higher in boys)19 and health insurance coverage.9,24 The province of Quebec posted the highest increase in ADHD, reaching close to 3.5 times the prevalence observed in 1999. Close to a 2-fold increase was also observed in Manitoba and Nova Scotia, with a smaller increase (1.04 times) in Ontario. Comparing the rates observed with Quebec and Ontario’s only reliable epidemiological surveys,25 the diagnosed annual prevalence has almost reached expected prevalence in boys aged 6 to 10 years but not in girls or in older age groups. When looking more closely at the male to female ratios, the ratio ranged from 2.4 to 2.8 in 2010. It was interesting to note that the male to female ratio ranged between 3.7 and 3.9 in 1999. The gap in ADHD diagnosis between boys and girls is getting smaller and may reflect increased identification of ADHD in girls, who more often exhibit symptoms of inattention, which may be more difficult to detect than hyperactivity.26–29 In the global burden of disease report, the male to female ratio was closer to 3.9.29

With regards to the incidence of ADHD, the data showed similar age and sex group distributions in all provinces. With the exception of Ontario, there was also an increasing trend in incidence reported in all provinces. Trends in prescribing in other universal health care systems such as the United Kingdom have shown an increasing trend in ADHD prescriptions in primary care in the past 10 years. Renoux et al.,30 in a cohort of close to 8 million primary care patients aged 6 to 45 years, showed an important increase in ADHD prescriptions since 2000, reaching close to 9 times the rates in 2015. A recent Canadian report also showed close to an 80% increase in ADHD prescriptions in adults between 2009 and 2014.31 Studies have also shown that prescription rates in males reach 5 times those of females. Furthermore, similar to the provincial diagnostic patterns we observed, access to more recent data from IMS Brogan showed an increase in the per capita number of analeptic prescriptions sold in 2010-2011 and 2011-2012 in Quebec (15.4 and 17.6), Nova Scotia (8.1 and 9.4), Ontario (7.2 and 7.9) and Manitoba (6.7 and 7.5).32

In the present study, general practitioners made the diagnosis of ADHD anywhere between 46% and 69% of incident cases observed in 2011 and 2012. This pattern might reflect the explicit guidelines provided to primary care clinicians by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) on the evaluation and treatment options for ADHD and referrals to specialists when other comorbid psychiatric disorders are present such as anxiety and depression.33 Data from Manitoba on physician specialty were not available for our study. The study by Brownell and Yogendran13 showed that children in Manitoba were primarily diagnosed by a paediatrician (58%), followed by general practitioners (27%) and psychiatrists (15%), in 1995-1996. When looking at our earliest data in 1999-2000, the data also showed that the majority of cases were diagnosed by paediatricians in Ontario and Quebec, whereas in Nova Scotia, general practitioners were more likely to diagnose cases. These variations in physician specialty in provinces may be due to availability and concentration of physician specialties.13

The prevalence and incidence estimates of ADHD presented in this article are based on administrative data in only 4 Canadian provinces where physician claims are captured. It would have been interesting to have data on the other provinces as this would have allowed for comparisons across the country. The provinces have publicly managed health care systems with fee-for-service payment schemes where many physicians file claims for reimbursement. With the exception of consultations with salaried physicians, who provide shadow billing, virtually all physician services rendered to residents are captured in all provinces. Administrative databases can therefore be used as monitoring tools providing timely information on health status across populations. When interpreting provincial estimates, however, one has to consider the proportion of salaried physicians in each province and assume similar rates of shadow billing, as well as the reliability and validity of reported diagnoses during consultations with physicians in inpatient and outpatient settings. A recent validation study in 1 province showed that physician payment plans (fee-for-service vs alternate payment plans) did not influence the accuracy of diagnoses reported in administrative databases.34 This also underlines the fact that health and social service contacts in schools and other community organisations with other professionals are not captured in health administrative data. Assessment of other conditions that are primarily diagnosed at younger ages such as developmental disabilities shows that health administrative data may miss a majority (55%-65%) of individuals experiencing these conditions.35 That said, using physician-diagnosed ADHD will have missed individuals diagnosed by mental health professionals such as school psychologists and whose parents opt for evidence-based parent and or teacher-administered behavior therapy before considering the use of medication for ADHD. Results from the US National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent (NCS-A) conducted between 2001 and 2004 showed that 73.8% of adolescents with ADHD had used services in the past year and that the most likely setting for mental health treatment was in schools (54.5%).36 Such variations in medical treatment of ADHD, due to different diagnostic and treatment practices for medication and psychological treatments for ADHD20,23 and parent preferences, may have in part explained the provincial variations observed.

Given that close to three-quarters of individuals with ADHD are prescribed drugs,9,12,13 one can assume that individuals would eventually consult a physician for a prescription, but it is not clear that the correct diagnosis will be attached to that consultation or what effect the black box warnings1,2 will have on prescription patterns. Youth in Ontario with ADHD are up to 18 times more likely to also present with anxiety and depression and 13 times and close to 4 times more likely to be prescribed an antipsychotic and antidepressant.12 This may lead physicians to code visits with diagnoses for which these medications are primarily indicated for in some cases. In this study, we only considered primary diagnoses, and therefore the prevalence and incidence rates may be underestimated. While previous reports have suggested that adding additional diagnoses to the case definition have only a negligible impact on estimates,5 this has been demonstrated primarily for more prevalent disorders such as mood or anxiety disorders, which can be diagnosed across the life span.6 Other work using administrative data for conditions diagnosed primarily in childhood (e.g., developmental disabilities) suggest that these conditions are not always captured in the main diagnostic field.37 Furthermore, the fact that the case definition required one diagnosis code may have led to an overestimation if the physician visit was to evaluate the presence of ADHD and not a diagnosis rendered. One should also consider that the overall prevalence and incidence of ADHD included children aged between 1 and 3 years. The clinical practice guidelines of the AAP,33 however, refer to children 4 years old and older, as younger children often exhibit ADHD-related symptoms due to their developmental stage. Including these young children may have led to a slight underestimation of the overall rates. Last, we do not have any information on the prescription of psychostimulants.

In conclusion, in this universal health care system, the prevalence and incidence of diagnosed ADHD did not increase uniformly, between 1999 and 2012, across all 4 provinces in Canada. Our findings illustrate the utility of provincial administrative databases that form part of the CDSS in monitoring diagnosed ADHD. Further surveillance could help inform whether ADHD is under- or overdiagnosed, as well as possible health, quality of life, and social consequences.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy for use of data contained in the Population Health Research Data Repository under project 2012/13-56. The results and conclusions are those of the authors, and no official endorsement by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Manitoba Health, or other data providers is intended or should be inferred. Data used in this study are from the Population Health Research Data Repository housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba and were derived from data provided by Manitoba Health. This work was also supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) and by the Population Health Research Unit (PHRU) in the Department of Community Health and Epidemiology at Dalhousie University (now Health Data Nova Scotia). The opinions, results, and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the supporting and funding sources. No endorsement by ICES, PHRU, or MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (201104SEC). Helen-Maria Vasiliadis is supported by a Senior Research Salary Award from the Quebec Health Region Fund (Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé) but otherwise has no competing interests. The other authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1. Health Canada. Updating of product monograph of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) drugs—for health professionals. 2009. www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/medeff/advisoriesavis/prof/_2006/adhd-tdah_medic_hpc-cps-eng.php. Accessed May 2017.

- 2. Government of Canada, Healthy Canadians. ADHD drugs may increase risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in some people; benefits still outweigh risks. 2015. http://healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2015/52759a-eng.php. Accessed May 2017.

- 3. Patrick K. Harnessing big data for health. CMAJ. 2016;188(8):555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Quan H, Williamson T. Guiding the reporting of studies that use routinely collected health data. CMAJ. 2016;188(8):559–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kisely S, Lin E, Lesage A, et al. Use of administrative data for the surveillance of mental disorders in 5 provinces. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(8):571–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kisely S, Lin E, Gilbert C, et al. Use of administrative data for the surveillance of mood and anxiety disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(12):1118–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of diagnosis and medication treatment for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder United States 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:842–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003-2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(1):34–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brault MC, Lacourse É. Prevalence of prescribed attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medications and diagnosis among Canadian preschoolers and school-age children: 1994-2007. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(2):93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Connolly RD, Speed D, Hesson J. Probabilities of ADD/ADHD and related substance use among Canadian adults [published online May 14, 2016]. J Atten Disord. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hauck TS, Lau C, Wing LL, et al. ADHD treatment in primary care [published online January 1, 2017]. Can J Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brownell MD, Yogendran MS. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in Manitoba children: medical diagnosis and psychostimulant treatment rates. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(3):264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, et al. A prospective 4-year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity and related disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(5):437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Claude D, Firestone P. The development of ADHD boys: a 12 year follow up. Can J Behav Sci. 1995;27:226–249. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCarthy S, Wilton L, Murray ML, et al. The epidemiology of pharmacologically treated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children, adolescents and adults in UK primary care. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pringsheim T, Lam D, Patten SB. The pharmacoepidemiology of antipsychotic medications for Canadian children and adolescents: 2005-2009. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(6):537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Mental health services in Australia. Mental health-related prescriptions. 2016. https://mhsa.aihw.gov.au/resources/prescriptions/. Accessed May 2017.

- 20. Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. ; RECORD Working Committee. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Visser SN, Blumberg SJ, Danielson ML, et al. State-based and demographic variation in parent-reported medication rates for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 2007-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Health care cost drivers: physician expenditure—technical report. Ottawa (ON): CIHI; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Waddell C, Offord DR, Shepherd CA, et al. Child psychiatric epidemiology and Canadian public policy-making: the state of the science and the art of the possible. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47(9):825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pastor PN, Reuben CA, Duran CR, et al. Association between diagnosed ADHD and selected characteristics among children aged 4-17 years: United States, 2011-2013. NCHS 2015; data brief 201. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boyle M, Georgiades K. Perspectives on child psychiatric disorder. In: Cairney J, Streiner D, editors. Mental disorder in Canada, an epidemiological perspective. Toronto (ON: ): Toronto University Press; 2010:205–226. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, et al. Clinical correlates of ADHD in females: findings from a large group of girls ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric referral sources. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(8):966–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quinn P, Wigal S. Perceptions of girls and ADHD: results from a national survey. Medscape J Med. 2004;6(2):2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levy F, Hay DA, Bennett KS, et al. Gender differences in ADHD subtype comorbidity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(4):368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Erskine HE, Ferrari AJ, Nelson P, et al. Epidemiological modelling of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(12):1263–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Renoux C, Shin JY, Dell’Aniello S, et al. Prescribing trends of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications in UK primary care, 1995-2015. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(3):858–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. Treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. 2015. http://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ADHD-Pepi-Report-Final_Dec-22-2015.pdf. Accessed May 2017.

- 32. IMS Brogan. Canadian CompuScript Audit. 2016. www.imsbrogancapabilities.com/en/market-insights/compuscript.html.

- 33. Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown RT, et al. ; Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cunningham CT, Jetté N, Li B, et al. Effect of physician specialist alternative payment plans on administrative health data in Calgary: a validation study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(4):E406–E412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lin E, Balogh R, Isaacs B, et al. Strengths and limitations of health and disability support administrative databases for population-based health research in intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2014;11:235–244. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Costello EJ, He JP, Sampson NA, et al. Services for adolescents with psychiatric disorders: 12-month data from the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(3):359–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lin E, Balogh R, Cobigo V, et al. Using administrative health data to identify individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a comparison of algorithms. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2013;57(5):462–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]