Abstract

We describe a fatal case of Japanese encephalitis virus infection following short-term travel to Thailand. Viral RNA was detected in urine and whole blood out to 26 and 28 days, respectively, after the onset of symptoms. Live virus was isolated from a urine specimen from day 14.

Keywords: flavivirus, Japanese encephalitis, PCR, urine, whole blood

CASE REPORT

A previously well 69-year-old Australian man traveled to Thailand in early May 2017. The planned duration of travel was 12 days, and he did not attend a travel clinic prior to departure. The patient did not take malaria chemoprophylaxis, nor did he have a prior history of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) vaccination. He flew to Phuket, before traveling north to the popular tourist destination of Khao Lak, where he stayed in a beachside holiday resort. Heavy rainfall occurred during the trip, which limited holiday activities. He did not travel to rural or remote areas, but did receive numerous mosquito bites. On the eighth day of travel, he became unwell with lethargy and generalized muscle aches. He flew to Bangkok on the ninth day of the trip, and over the following 3 days his symptoms included ongoing lethargy, poor appetite, and drenching sweats, but no headache, meningism, or confusion. He returned to Australia on day 12 of travel and was admitted to a regional hospital the following day, now the fifth day after symptoms commenced (Figure 1).

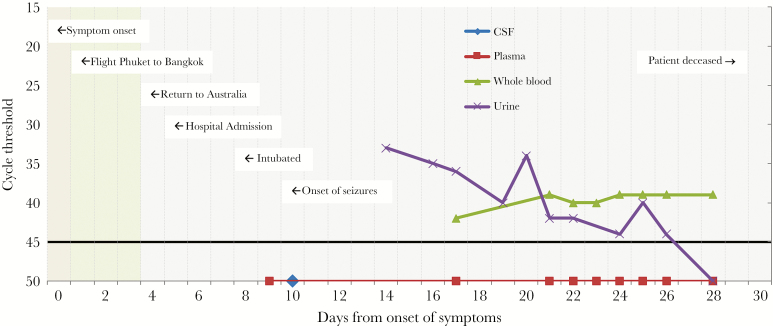

Figure 1.

Timeline of events and real-time polymerase chain reaction cycle threshold values (mapped as days after the onset of symptoms) for cerebrospinal fluid, plasma, whole blood, and urine. A cutoff for a negative result was a cycle threshold of 45 (black horizontal line).

Shortly after admission, on day 7 of his illness, he became confused. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained by lumbar puncture demonstrated a glucose of 3.5 mmol/L (reference interval, 2.2–3.9 mmol/L), protein of 1.3 g/L (reference interval < 0.45), polymorphs of 280 × 10^6/L, lymphocytes of 90 × 10^6/L, and red blood cells of 54 × 10^6/L. He was commenced on empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics with vancomycin, meropenem, benzyl penicillin, and acyclovir. Due to a deteriorating conscious state, he was intubated the following day and transferred to a tertiary center. Neurological examination upon arrival revealed a generalized flaccid paralysis. A magnetic resonance image of the brain demonstrated no abnormalities. Seizure activity developed on day 10 of his illness, for which anticonvulsant medication was commenced.

Diagnostic assays performed on the initial and a repeat CSF (on day 10) were negative using conventional gel-based and real-time multiplex polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for herpes viruses (herpes simplex 1 and 2 and varicella zoster), enterovirus, pan-flavivirus (Murray Valley encephalitis [MVE], Kunjin, dengue, West Nile, Zika, yellow fever, JEV), respiratory viruses (influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza, human metapneumovirus, picornavirus, adenovirus, coronavirus), meningococcus, and pneumococcus. The conventional pan-flavivirus PCR and JEV real-time PCR performed on plasma were also negative (see the Supplementary Data for detailed methods). HIV and syphilis serology were negative, as were bacterial cultures and screening swabs for Burkholderia pseudomallel.

On the fourteenth day of illness, JEV immunofluorescence serology (Euroimmun) performed in parallel on plasma from day 7, day 12, and day 13 of illness, was positive. The JEV IgG titre increased across the serial bleeds from 160 to 1280 to >2560 (confirmed by neutralization), suggesting recent infection, and JEV IgM was detected in all 3 specimens. Serology performed on CSF from day 10 was also positive for JEV IgM and IgG. The presence of measles IgG in plasma but not CSF was consistent with local production of JEV antibodies in CSF rather than contamination. Serology for MVE (EIA—total antibody) was weakly positive on day 7 but negative on days 12 and 13 and thought to represent nonspecific cross-reactivity. Dengue virus IgM, IgG, and NS1 antigen were not detected.

Given the results of serological testing, serial samples of plasma, whole blood, and urine were tested using the conventional gel based pan-flavivirus PCR and JEV real-time PCR. Notably, both urine and whole blood specimens were found to be persistently positive for JEV (confirmed by sequencing of the NS5 region), while plasma was found to be persistently negative (Figure 1). Reproducibility of these findings was confirmed by re-extracting and retesting the 4 most recent urine and whole blood specimens directly from the primary samples, and repeat testing was performed on separate PCR runs. Whole-genome sequencing and subsequent phylogenetic analysis (Supplementary Figure 1) identified the isolated JEV strain (VIDRL_JEV aligned) as a member of Genotype I. Our patient’s isolate localized within a subclade of viruses isolated from Thailand, geographically aligning with the travel history.

Aliquots of urine and whole blood were inoculated onto cultured cells to assess viral infectivity (see the Supplementary Data for detailed methods). Cytopathic effects were observed 7 days postinoculation from the day 14 urine specimen. The cell culture supernatant was tested by JEV real-time PCR and was found to be positive with a high level of detection, suggesting efficient viral replication.

Japanese encephalitis viral RNA was detected in urine samples out to day 26 after the onset of symptoms and in whole blood up until the final specimen was tested on day 28.

Electromyogram and nerve conduction studies performed on day 22 were consistent with an acute motor-axonal neuropathy or anterior horn cell pathology. No clinical improvement was evident after 4 days of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) administered at a dose of 1 g/kg daily, and the patient died 30 days after the onset of symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Japanese encephalitis virus is a mosquito-borne flavivirus endemic in most parts of Asia, where it is the most common vaccine-preventable cause of encephalitis and a major cause of morbidity and mortality. In a 2011 systematic review, it was estimated that 67 900 cases occur annually [1]. The traditional diagnostic paradigm for JEV infection has been based on the understanding that the period of viremia is short-lived, and hence the utility of PCR is limited. As a result, most cases are diagnosed serologically [2]. Serological diagnosis may be complicated by cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses or the need for follow-up samples to look for a rise in antibody titre over time. Here we report prolonged detection of JEV in both urine and whole blood, but not in plasma or CSF samples, which are most commonly tested for diagnostic purposes. If reproducible in other cases, these findings could significantly improve laboratory diagnostics for JEV and provide new insights into the viral dynamics of JEV.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported detection of JEV RNA in whole blood and the first report of JEV isolation in cell culture from urine. This is an interesting finding in light of recent detection of a number of other flaviviruses in urine samples, including Zika, Dengue, and West Nile Virus (WNV) [4–5]. This is only the second reported case of detection of JEV RNA in urine, with the first reported case initially detected via deep sequencing [6]. We demonstrate prolonged detection of JEV in urine to day 26. These findings are in contrast to a report from China, where JEV RNA was not detected by real-time PCR from the urine of 52 children with serologically confirmed infection [7]. Our experience with a single, possibly exceptional case has been different, and the reasons why are not clear. This might reflect differences in the patients studied, the diagnostic assays employed, or the timing of the urine samples collected. Our PCR assay targeted loci within the NS5 region, in contrast to the consensus NS3 region targeted in the previous report. Alternatively, in the previous report [7], all urine specimens were collected early on in illness (3–9 days after onset) whereas the first urine specimen tested in our patient was 14 days after the onset of symptoms.

In light of previous descriptions of prolonged detection of Dengue, Zika, and West Nile virus from whole blood specimens [3, 8–10], we undertook serial testing of whole blood in parallel with testing of plasma. JEV RNA was detectable in whole blood, but not plasma, out to the final specimen tested, 28 days after the onset of illness. Testing of whole blood by PCR has not traditionally been performed due to the potential presence of inhibitors [11]; however, this report and other recent publications suggest that testing of whole blood may offer additional diagnostic information in certain situations. Notably, West Nile virus has been found to bind to red blood cells (RBCs), and the WNV viral load in RBC components has been found to exceed that in plasma by 1 order of magnitude [12].

Japanese encephalitis is a rare infection in travelers, with only 79 cases among travelers or expatriates from nonendemic countries reported to the Centers from Disease Control and Prevention from 1973 to 2015 [13]. Vaccination to JEV is generally only recommended to travelers who intend to spend 1 or more months in endemic areas during the transmission season, although consideration may be given to short-term travelers who may be at increased risk of exposure or who plan to travel to an area with an ongoing outbreak [13]. A further notable aspect of our case is acquisition of JEV following short-term travel to an area that would not normally be considered high risk. Interestingly, in a 2009 review on JEV in travelers, more than half of 21 cases were acquired after short-term travel [14]. Given the improved tolerability of modern vaccine preparations and the potentially devastating consequences of infection, it has been suggested that current vaccination recommendations should be revised to offer vaccination to a broader range of travelers [14]. A short-term traveler who visits JEV endemic areas should be informed about the risk of disease, potential outcomes, and the risks and benefits of JEV vaccination.

In conclusion, this report raises a potential opportunity to widen the diagnostic window for JEV infection. Given the challenges inherent in flavivirus serological diagnosis, especially in the context of lifetime exposures to multiple flaviviruses, a greater capacity for direct virus detection by PCR could be very attractive. Further studies are needed to determine the reproducibility of these findings.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online (ofid.oxfordjournals.org). Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Written informed consent was obtained from the next of kin for the publication of this case report.

We would like to thank the Royal Melbourne Hospital Neurology Unit for advice and input into caring for the patient. We would like to thank the Royal Melbourne Hospital Microbiology Department for collecting and transporting patient samples. We would like to thank the Royal Melbourne Hospital Intensive Care Unit for caring for the patient and assistance in collecting and transporting patient samples. We would like to thank Micromon (Monash University) for their assistance with library preparation and next-generation sequencing.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Campbell GL, Hills SL, Fischer M et al. . Estimated global incidence of Japanese encephalitis: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2011; 89:766–74, 774A–774E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Manual for the laboratory diagnosis of Japanese encephalitis virus infection Available at: http://www.wpro.who.int/immunization/documents/Manual_lab_diagnosis_JE.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2017.

- 3. Murray KO, Gorchakov R, Carlson AR et al. . Prolonged detection of Zika virus in vaginal secretions and whole blood. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:99–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van den Bossche D, Cnops L, Van Esbroeck M. Recovery of dengue virus from urine samples by real-time RT-PCR. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2015; 34:1361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nagy A, Ban E, Nagy O et al. . Detection and sequencing of West Nile virus RNA from human urine and serum samples during the 2014 seasonal period. Arch Virol 2016; 161:1797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mai NTH, Phu NH, Nhu LNT et al. . Central nervous system infection diagnosis by next-generation sequencing: a glimpse into the future? Open forum Infect Dis 2017; 4: doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao H, Wang YG, Deng YQ et al. . Japanese encephalitis virus RNA not detected in urine. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:157–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mansuy JM, Mengelle C, Pasquier C et al. . Zika virus infection and prolonged viremia in whole-blood specimens. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23:863–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lanteri MC, Lee TH, Wen L et al. . West Nile virus nucleic acid persistence in whole blood months after clearance in plasma: implication for transfusion and transplantation safety. Transfusion 2014; 54:3232–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klungthong C, Gibbons RV, Thaisomboonsuk B et al. . Dengue virus detection using whole blood for reverse transcriptase PCR and virus isolation. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:2480–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilson IG. Inhibition and facilitation of nucleic acid amplification. Appl Environ Microbiol 1997; 63:3741–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rios M, Daniel S, Chancey C et al. . West Nile virus adheres to human red blood cells in whole blood. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hills SL, Rabe IB, Fischer M. Japanese encephalitis. In: CDC Yellow Book. Oxford University Press; 2017. Available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/japanese-encephalitis. Accessed 10 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buhl MR, Lindquist L. Japanese encephalitis in travelers: review of cases and seasonal risk. J Travel Med 2009; 16:217–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.