Abstract

Background

In order to increase treatment coverage, antiretroviral treatment (ART) is provided through primary health care in low-income high-burden countries, where tuberculosis (TB) co-infection is common. We investigated the long-term outcome of health center–based ART, with regard to concomitant TB.

Methods

ART-naïve adults were included in a prospective cohort at Ethiopian health centers and followed for up to 4 years after starting ART. All participants were investigated for active TB at inclusion. The primary study outcomes were the impact of concomitant TB on all-cause mortality, loss to follow-up (LTFU), and lack of virological suppression (VS). Kaplan-Meier survival estimates and Cox proportional hazards models with multivariate adjustments were used.

Results

In total, 141/729 (19%) subjects had concomitant TB, 85% with bacteriological confirmation (median CD4 count TB, 169 cells/mm3; IQR, 99–265; non-TB, 194 cells/mm3; IQR, 122–275). During follow-up (median, 2.5 years), 60 (8%) died and 58 (8%) were LTFU. After ≥6 months of ART, 131/630 (21%) had lack of VS. Concomitant TB did not influence the rates of death, LTFU, or VS. Male gender and malnutrition were associated with higher risk of adverse outcomes. Regardless of TB co-infection status, even after 3 years of ART, two-thirds of participants had CD4 counts below 500 cells/mm3.

Conclusions

Concomitant TB did not impact treatment outcomes in adults investigated for active TB before starting ART at Ethiopian health centers. However, one-third of patients had unsatisfactory long-term treatment outcomes and immunologic recovery was slow, illustrating the need for new interventions to optimize ART programs.

Keywords: antiretroviral treatment, Ethiopia, HIV, outcome, tuberculosis

Many reports on antiretroviral treatment (ART) outcomes in cohorts from low-income countries have shown results comparable with those in high-income settings, albeit with higher rates of early mortality, probably related to more advanced disease at ART initiation [1–3]. In order to increase ART coverage further in high-burden countries, provision of ART is increasingly managed by nurses and integrated within existing primary health care systems [4]. According to recent estimates, >18 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) have started ART [5], but to reach the goal of 90% treatment coverage, almost as many persons in addition need to start ART. Further attention to achieving 90% rates of virological suppression in persons starting ART is also required. Recent data show high rates of loss to follow-up (LTFU) in ART recipients [6, 7], as well as rising occurrence of both acquired and transmitted antiretroviral drug resistance [8, 9].

Although the median CD4 cell counts at ART initiation have increased during recent years [10], many patients in Sub-Saharan Africa still have severe immunosuppression when HIV is diagnosed and ART can be started [11]. Furthermore, tuberculosis (TB) co-infection is common [12] and has been associated with worse ART outcomes [13], including persistently elevated rates of death [14]. As the clinical manifestations of TB may be atypical and vague in PLHIV, TB is frequently missed [15]. Active TB case-finding has therefore been proposed as an intervention that could improve outcomes of patients with TB/HIV co-infection [16].

We have previously reported similar 6-month outcomes irrespective of concomitant TB in adults categorized for active TB before starting ART at Ethiopian health centers [17]. Here we aimed to compare long-term ART outcomes with regard to concomitant TB in these patients and to identify factors associated with mortality, LTFU, and lack of virological suppression.

METHODS

Setting

This study was performed in Ethiopian public health centers in and around Adama (population, ~600 000). Nonphysician clinicians provide all care at Ethiopian health centers, including management of TB and HIV. Since 2006, ART has been decentralized in Ethiopia by inclusion of an ART clinic in many health centers.

In 2012, the Ethiopian National ART guidelines recommended ART for all patients with CD4 counts <350 cells/mm3 and/or World Health Organization (WHO) stage 4 [18]. In 2015, these guidelines were revised, with a higher CD4 count threshold for ART initiation at <500 cells/mm3 [19], with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)–based first line ART regimens in both versions. Second-line ART is provided at hospital-based clinics to which patients with suspected treatment failure are referred.

At the time of this study, viral load (VL) determination was only performed in case of suspected treatment failure, based on immunological and clinical criteria [19].

Study Participants

The study cohort has previously been described [17, 20]. HIV-positive adults presenting to any of the five public health centers providing ART in the study uptake area from October 2011 until March 2013 were considered for inclusion. Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, eligibility to start ART (defined as a documented CD4 count <350 cells/mm3 and/or WHO stage 4 disease), and residence within the catchment area of the study sites. Patients reporting current or previous ART, or TB treatment for more than 2 weeks before inclusion, were excluded.

At inclusion, sociodemographic and medical information was collected following structured questionnaires. Blood samples were obtained for CD4 counts, with storage of plasma aliquots at −80°C for VL testing. Medical information was updated at subsequent visits, along with repeated blood sampling. Patients were followed 3-monthly until ART initiation, whereby follow-up visits were scheduled for months 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12, and biannually thereafter until study closure on December 31, 2015.

At inclusion, all participants, regardless of symptoms suggestive of TB, were requested to submit 2 pairs of spontaneously expectorated morning sputum samples for TB investigations (smear microscopy, GeneXpert MTB/RIF, and liquid culture) [20]. Subjects with peripheral lymphadenopathy were also referred for fine-needle aspiration for TB investigations. Participants who did not provide any sample for TB investigations were excluded.

Clinicians were instructed to repeat TB diagnostics according to the study protocol during follow-up in case of clinically suspected TB. All subjects diagnosed with TB within 3 months after starting ART were considered TB cases, with the remaining subjects considered non-TB cases. Patients diagnosed with TB ≥3 months after starting ART (incident TB) were considered non-TB cases for the outcome analyses. TB cases were further categorized with regard to whether TB was bacteriologically confirmed or diagnosed on clinical grounds.

VL was performed in batches during the study period using the Abbott Real-Time HIV-1 assay (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, IL; detection limit 40 copies/mL) or the Abbott m2000 RealTime System Automated molecular platforms (Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, IL; detection limit 150 copies/mL) with communication of results to care providers. In line with national guidelines, subjects with VL ≥1000 copies/mL underwent adherence counseling followed by repeat VL testing before referral for second-line ART [19].

During follow-up, tracing was recommended for patients more than 1 day late for a scheduled visit. Subjects more than 3 months late for a scheduled visit and who did not return during follow-up were considered LTFU.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of patient characteristics between TB cases and non-TB cases was performed using Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. All analyses were based on subjects with complete data regarding the variable(s) under study.

The primary study outcomes were rates of adverse ART outcomes (all-cause mortality, LTFU, and lack of VS) with regard to TB category at ART start. The secondary outcome was immunologic recovery during ART.

In the mortality and LTFU analyses, time-at-risk started at ART initiation, whereas time-at-risk for virological outcome analysis started 6 months after ART initiation. For each outcome, subjects were followed until reaching the respective outcome, with censoring of remaining subjects at the last registered visit. Subjects without subsequent follow-up visits after ART initiation were assigned 0.1 months’ follow-up time so that they would contribute to the survival analyses. Virological outcomes were categorized as virological suppression (VS; VL < 150 copies/mL), low-level viremia (LLV; VL 150–1000 copies/mL), and high-level viremia (HLV; VL > 1000 copies/mL). Any event of HLV recorded during follow-up 6 months after ART initiation was defined as lack of VS. All subjects with at least 1 VL result during follow-up were included in this analysis.

Kaplan-Meier plots were used to graphically assess the temporal distribution of events, and the log rank test was used to compare subjects with and without TB. Cox proportional hazards models were used with adjustment for variables with previously reported associations with the outcomes. Whereas age was kept as a continuous variable, CD4 counts were categorized according to level of immunosuppression (<100, 100–200, 201–350, and >350 cells/mm3, respectively), and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) was dichotomized at gender-specific thresholds (<23 cm for women and <24 cm for men). All variables included in the models were assessed for the proportional hazards assumption using log-minus-log plots and Schoenfeld residuals.

Two sensitivity analyses were performed. First, subjects with clinically diagnosed TB were excluded from the survival models to assess the impact of only bacteriologically confirmed TB. Second, to assess whether intervals without available VL results during follow-up had any impact on the analysis of HLV, subjects with less than 1 VL per year had their follow-up censored at last VL before such an interval.

Immunological recovery during ART was described using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) comparing TB cases and non-TB cases using the Mann-Whitney U test at each follow-up.

All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 21 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY), and STATA, version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A P value <.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the national Research Ethics Review Committee at the Ministry of Science and Technology of Ethiopia and the Regional Ethical Review Board of Lund University, Sweden. All study participants provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

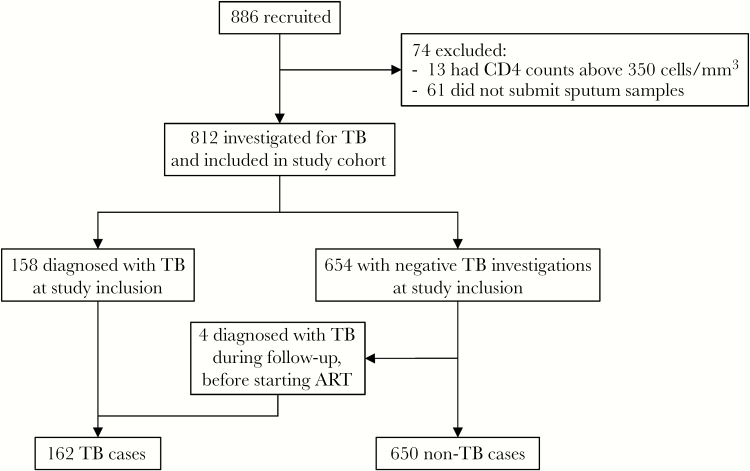

Out of 886 subjects identified as potentially eligible for inclusion, 812 were included (Figure 1). Characteristics of the 61 excluded subjects who did not submit samples for TB investigations did not differ significantly from those included (Table 1, Supplementary Material).

Figure 1.

Study participant flow chart. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; TB, tuberculosis.

Active TB was diagnosed in connection with inclusion in 158/812 (19%) participants, with bacteriologic confirmation in 137/158 (87%). An additional 4 subjects were diagnosed during follow-up before starting ART (1/4 bacteriologically confirmed) (Figure 1).

During a median follow-up time of 3.0 years (IQR, 2.1–3.4 years), 729 (90%) started ART. At study closure, 525 (72%) of subjects starting ART remained in care, whereas 60 (8%) had died, 58 (8%) were LTFU, 80 (11%) had reported transfer of care, and 6 (1%) had declined further participation in the study. Eighty-three subjects did not start ART during study follow-up (censoring event: death, 22; LTFU, 31; transfer of care, 23; declined further study participation, 4; end of study, 3).

Characteristics of study participants at ART initiation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cohort Participants at Start Antiretroviral Therapy

| Total (n = 729) |

TB Cases (n = 141) |

Non-TB Cases (n = 588) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 431 (59) | 65 (46) | 366 (62) | <.01 |

| Age, y | 32 (28–40) | 34 (28–40) | 32 (28–40) | .49 |

| MUAC, cm | 23.0 (21.0–25.0) | 21.5 (20.0–23.5) | 23.0 (21.0–25.0) | <.01 |

| MUACa, <23 cm/<24 cm | 385 (53) | 99 (70) | 286 (49) | <.01 |

| CD4 count, median cells/mm3 | 187 (116–274) | 169 (99–265) | 194 (122–275) | .03 |

| <100 | 138 (19) | 36 (26) | 102 (17) | |

| 100–200 | 264 (36) | 52 (37) | 212 (36) | |

| 201–350 | 237 (33) | 35 (25) | 202 (35) | |

| >350 | 88 (12) | 18 (13) | 70 (12) | |

| Time to ART start, mo | 1.2 (0.5–5.1) | 1.6 (0.9–3.4) | 1.1 (0.5–5.5) | .04 |

| Initial ART regimenb | ||||

| NNRTI | ||||

| Efavirenz | 612 (84) | 132 (94) | 480 (82) | <.01 |

| Nevirapine | 115 (16) | 8 (6) | 107 (18) | <.01 |

| NRTI | ||||

| Tenofovir | 643 (88) | 130 (93) | 513 (87) | .07 |

| Zidovudine | 72 (10) | 6 (4) | 66 (11) | .01 |

| Stavudine | 12 (2) | 4 (3) | 8 (1) | .26 |

Data presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range). P value derived using Mann-Whitney U, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

Abbreviations: MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI, nucleos(t)ide transcriptase inhibitor; TB, tuberculosis.

aMUAC dichotomized at <23 cm for women and <24 cm for men.

bAll regimens included lamivudine.

Mortality

During 1643 person-years of follow-up after ART start, death was recorded in 12/141 (9%) TB cases and 48/588 (8%) non-TB cases. The median time from ART start to death was 8.6 months (IQR, 2.2–17.4 months), with 26 deaths (43%) occurring within 6 months of ART start. VL was available prior to time of death for 26/34 (76%; median duration from VL to death, 4.9 months; IQR, 3.4–7.4 months); 14 (54%) were virally suppressed, 11 (42%) had HLV, and 1 (4%) had LLV.

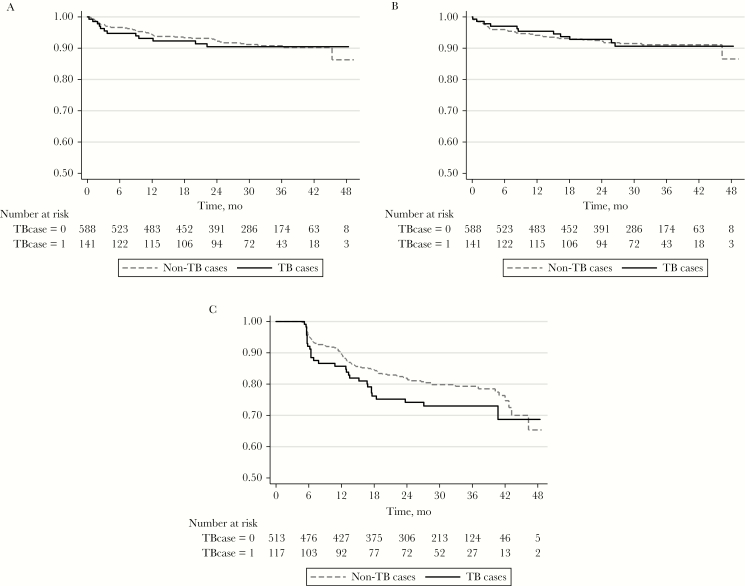

TB was not associated with risk of death during ART (log rank P = .85) (Figure 2, panel A). In the unadjusted survival analysis, low MUAC was significantly associated with mortality. This association remained after multivariate adjustments (Table 1). Men had a trend toward higher risk of mortality in unadjusted analysis (P = .06), but this trend did not remain after multivariate adjustments.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots for TB cases and non-TB cases regarding mortality (A), loss to follow-up (B), and high-level viremia (C). Abbreviation: TB, tuberculosis.

Loss to Follow-up

Among 58 subjects lost to follow-up after ART initiation, 27/58 (47%) were lost within 6 months of ART start. In total, 11/141 (8%) TB cases and 47/588 (8%) non-TB cases were LTFU a median 6.6 months (IQR, 2.0–15.5 months) after starting ART (log rank P = .93) (Figure 2, panel B). VL was available prior to time of LTFU for 28 subjects (median duration from VL to last visit in study, 1.2 months; IQR, 0.0–4.8 months); 21 (75%) were virally suppressed, 6 (21%) had HLV, and 1 (4%) had LLV.

In unadjusted analysis, men had an increased risk of LTFU, and this association remained after multivariate adjustments (Table 1). MUAC was not included in the multivariate model as the proportional hazards assumption was not fulfilled due to a disproportionally higher risk of LTFU shortly after starting ART in subjects with lower MUAC, compared with later during follow-up.

Virological Suppression

Six-hundred-thirty participants met criteria for inclusion in the virological outcome analysis. Among the 99 excluded subjects, 80 had less than 6 months of follow-up after ART start (death, 26; LTFU, 27; transfer-out, 21; declined further participation, 2; ART start within 6 months of study closure, 4), and from 19 subjects no VL results were available during follow-up.

The 630 participants included in the virological outcome analysis had a median of 4 VL results after ≥6 months of ART (IQR, 3–5 viral loads). In total, 426 (68%) were virally suppressed on all occasions, 73 (12%) had LLV on at least 1 occasion, and 131 (21%) had HLV on at least 1 occasion. These proportions were similar when based on subjects with at least 2 VLs (n = 591) during follow-up: 405 (69%) were virally suppressed on all occasions, 55 (9%) had LLV on at least 1 occasion, and 131 (22%) had HLV on at least 1 occasion.

A similar proportion of TB cases (26%) and non-TB cases (20%; P = .15), had at least 1 occasion of HLV after ≥6 months of ART (lack of virological suppression). The median time from ART start to this event was 11.8 months (IQR, 6.0–17.5 months).

In survival analysis, TB was not significantly associated with HLV (log rank P = .14) (Figure 2, panel C). In unadjusted analysis, male gender, CD4 count <100 cells/mm3, and low MUAC were associated with HLV. The associations remained after multivariate adjustments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted and Unadjusted Hazard Ratios for Mortality, LTFU, and Lack of Virological Suppression After ART Initiation

| Variable | Mortality | LTFU | Lack of Virological Suppression | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) |

P | aHR (95% CI) |

P | HR (95% CI) |

P | aHR (95% CI) |

P | HR (95% CI) |

P | aHR (95% CI) |

P | |

| TB case | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) |

.85 | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) |

.62 | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) |

.99 | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) |

.76 | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) |

.15 | 1.0 (0.7–1.6) |

.88 |

| Men | 1.6 (1.0–2.7) |

.06 | 1.3 (0.8–2.3) |

.29 | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) |

.04 | 2.0 (1.2–3.5) |

.01 | 2.1 (1.5–3.0) |

<.01 | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) |

<.01 |

| Age, per year |

1.0 (1.0–1.0) |

.47 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) |

.85 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) |

.25 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) |

.07 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) |

.84 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) |

.21 |

| CD4 >350, cells/mm3 |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| CD4 201–350, cells/mm3 |

1.0 (0.4–2.4) |

.92 | 1.2 (0.5–3.1) |

.67 | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) |

.64 | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) |

.64 | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) |

.89 | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) |

.63 |

| CD4 100–200, cells/mm3 |

0.8 (0.3–2.1) |

.71 | 0.9 (0.4–2.4) |

.86 | 1.5 (0.6–3.7) |

.34 | 1.6 (0.6–3.7) |

.33 | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) |

.52 | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) |

.33 |

| CD4 <100, cells/mm3 |

2.1 (0.8–5.1) |

.12 | 1.8 (0.7–4.5) |

.20 | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) |

.90 | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) |

.87 | 2.5 (1.3–4.9) |

.01 | 2.3 (1.2–4.5) |

.01 |

| MUACa, <23 cm/<24 cm |

3.5 (1.9–6.5) |

<.01 | 3.1 (1.7–5.9) |

<.01 | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) |

.25 | b | 2.5 (1.7–3.7) |

<.01 | 2.1 (1.4–3.1) |

<.01 | |

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LTFU, lost to follow-up; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference.

aMUAC dichotomized at <23 cm for women and <24 cm for men.

bMUAC did not fulfill the proportional hazards assumption for LTFU; therefore it is not included in the multivariate model.

To assess possible interaction between gender and the other variables, gender-stratified models were fitted. TB remained without association with HLV for both men (P = .35) and women (P = .47). For men, younger age was associated with an increased risk of HLV (P = .03), whereas remaining variables had similar associations with HLV for both men and women compared with the unstratified analysis.

Subsequent VL data were available for 98/131 (75%) subjects with HLV. Of these, 43 had VS on at least 1 subsequent occasion (without recorded change of ART regimen in 34/43), 9 had LLV on at least 1 occasion, and 63 had HLV on at least 1 occasion.

Of the 522 participants remaining in care at end of follow-up, VL results were available for 516 (99%). The final virological statuses of these were 445 (86%) VS, 23 (5%) LLV, and 48 (9%) HLV, respectively.

Sensitivity Analyses

Twenty-two TB cases without bacteriological confirmation were excluded in a sensitivity analysis, with resulting multivariate models remaining largely unchanged (Table 2, Supplementary Material).

Eight subjects were excluded due to lack of VL data at 6 and 12 months after ART start, and an additional 26 subjects had their follow-up censored at last VL before a testing gap in the second sensitivity analysis. TB remained without significant association with HLV (log rank P = .15). The multivariate model remained unchanged (Table 3, Supplementary Material).

Immunological Recovery

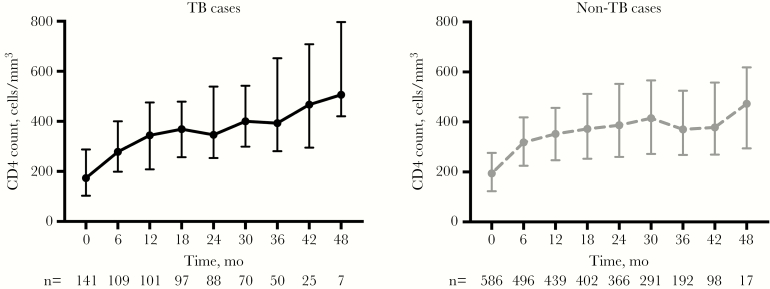

Participants with TB had lower CD4 counts at ART start (P = .03) (Table 1). By 6 months, the median CD4 count remained lower in TB cases (267 cells/mm3; IQR, 199–390) compared with non-TB cases (318 cells/mm3; IQR, 225–414 cells/mm3; P = .04). At 12 months, however, median CD4 counts did not differ significantly for TB cases and non-TB cases (343 cells/mm3; IQR, 210–418 cells/mm3; vs 352 cells/mm3; IQR, 246–456 cells/mm3; P = .58). The similar CD4 count distribution among TB cases and non-TB cases remained during subsequent follow-up (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Immunologic recovery in antiretroviral therapy recipients with regard to concomitant tuberculosis (plots with medians and interquartile ranges). Abbreviation: TV, tuberculosis.

Assessing whether early attrition influenced the apparent immunologic recovery, subjects with less than 6 months of follow-up after ART start (n = 80) were excluded in an additional analysis. This did not affect the overall results (data not shown).

Incident TB

In total, 14 subjects had incident TB during 1935 person-years of study follow-up, which equals a TB incidence of 7.2/1000 person-years. Bacteriological confirmation was obtained in 8/14 (57%). The number of incident TB cases did not suffice for additional analyses with regard to immunological recovery and risk of incident TB.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of adults starting ART at Ethiopian health centers, a high proportion (86%) of subjects remaining in care had virological suppression at a median of 2.5 years after starting ART, irrespective of concomitant TB. These results are in line with a recent meta-analysis on firstline ART outcome in Sub-Saharan Africa, reporting virological suppression in more than 80% for up to 60 months of ART [21].

TB is considered to be the leading cause of death in PLHIV in low-income countries [4], and TB co-infection has been associated with increased mortality both before and after starting ART [22, 23]. In this cohort, however, concomitant TB did not influence the long-term risk of death, nor rates of LTFU or VS. All participants underwent intensified TB case-finding at inclusion, regardless of clinical presentation. It is likely that this strategy led to reduced mortality in co-infected patients.

Our results support that providing ART to PLHIV with TB is feasible and effective at health center level, with similar rates of virological suppression for both groups. These results are in agreement with a meta-analysis showing no influence of TB status at the start of ART on virological suppression [24], but in contrast to our study most previous investigations of this issue have been performed at hospitals or specialized HIV clinics. Due to heterogeneity and inconclusiveness in available data, the risk of virological failure could not be assessed in that meta-analysis. However, in a previous study from South Africa (not included in the meta-analysis) with a high proportion of bacteriologically confirmed TB cases, TB at start of ART was associated with an increased risk of virological failure [13].

Nearly 80% of participants in our cohort had persistent viral suppression <1000 copies/mL. However, in an intention-to-treat analysis assuming subjects who were LTFU or died after starting ART to have lack of virological suppression, the treatment success rate declined to 67%. These results are in line with intention-to-treat estimates from Sub-Saharan Africa [21].

For our study, we chose to use the occurrence of VL >1000 copies/mL after at least 6 months ART to define lack of virological suppression. Among patients with available VL data, 21% of patients had at least 1 episode of HLV. Although current guidelines require 2 VL measurements above this threshold to define virological failure, the majority of patients with recorded HLV had persistent viremia in follow-up samples. Furthermore, as drug resistance mutations can accumulate rapidly during periods of HLV in ART recipients [25, 26], with subsequent risk of virological treatment failure [27], we think that even isolated episodes of HLV should be regarded as unsatisfactory treatment outcomes. In addition, drug-resistant strains can be transmitted onwards [8].

The likelihood of HLV was increased among men, subjects with CD4 counts <100 cells/mm3, and those with low MUAC. Low CD4 counts at ART initiation have previously been associated with lower rates of virological suppression during ART [13, 28], and other studies have also observed higher risk of virological failure in men [29, 30]. The underlying reason for the independent association between low MUAC and HLV is not obvious and may be related to factors not included in our analysis.

Although we did not find any gender-related difference regarding mortality, in contrast to other reports [31, 32], malnutrition, measured by the gender-specific MUAC thresholds of <23 cm for women and <24 cm for men, was associated with a more than 3-fold increase in risk of death after starting ART. The association between low MUAC and mortality in PLHIV has been found by other researchers [33] and might be due to the presence of unrecognized opportunistic infections, including cases of TB not identified by our intensified case-finding protocol. This is in accordance with autopsy studies from Sub-Saharan Africa, demonstrating that TB is a common finding even among PLHIV who have undergone TB investigations before death [34, 35].

Low MUAC was also associated with LTFU during the first 4 months after starting ART, which suggests that unreported mortality may explain LTFU in a subgroup of individuals during this period. This is in line with findings from South Africa that showed an elevated risk of death soon after becoming LTFU but not later [28]. Similarly, increased mortality was found in South African patients within 3 months after registered transfer of care [36]. In our cohort, transfer of care was noted in 11% of subjects, with similar proportions irrespective of concomitant TB. We were unable to assess the subsequent outcomes of these patients.

Previous studies have indicated that TB may negatively affect immunological recovery during ART [37–40], and it has been speculated that the increased risk of death after completion of TB treatment noted in some studies is related to persistent immunosuppression [14, 37, 38]. At 6 months after starting ART, we observed lower median CD4 cell counts in co-infected patients [17], but during longer follow-up this difference disappeared among subjects who remained in care. Yet, regardless of TB co-infection status, even after 3 years of ART, nearly two-thirds of participants had CD4 counts below 500 cells/mm3, which is considered to represent the lower normal reference level. This phenomenon illustrates the need for earlier diagnosis and ART initiation during the course of HIV infection.

This study was based at public health centers providing nurse-based care, a representative setting where many PLHIV receive ART globally. Through active case-finding for TB at inclusion into the study cohort, most subjects with concomitant TB were diagnosed with bacteriological confirmation. Furthermore, active case-finding allows for detection of active TB at earlier stages during the disease course. It should be noted, however, that our protocol was focused on pulmonary and peripheral lymph node TB; thus, other types of TB might have been missed.

Some limitations should also be noted. First, subjects included in this study were required to be ART-naïve and to meet criteria for starting ART according to Ethiopian recommendations in use during 2012–2015. Therefore, it is not certain that our findings apply to patients with previous ART exposure or to those with less advanced HIV disease. Second, we could not determine causes of death for deceased participants. Although a proportion of deaths could be due to TB [34, 35], it has been suggested that conditions not directly associated with HIV account for an increasing proportion of deaths occurring later during ART [32]. Primarily by telephone calls to the family of the deceased, we could ascertain that most deaths in our study were due to illness and not attributable to accidents or other unnatural causes. Finally, we did not have drug resistance data for subjects with HLV.

In conclusion, we found no impact of concomitant TB on treatment outcomes in adults initiating ART at decentralized facilities in Ethiopia. Overall, one-third of patients initiating ART had unsatisfactory long-term treatment outcomes, with higher risk for men and malnourished individuals. Our findings support screening for TB and provision of ART to TB co-infected patients at health center level, but also illustrate the need for better treatment monitoring and interventions to optimize outcomes.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the patients who participated in the study as well as to the staff members at the health centers and the Adama Regional Laboratory for their work with this study. We also acknowledge our data management team, led by Gadissa Merga, who contributed greatly to this study. We are also grateful for the excellent collaboration with the Oromia Regional Health Bureau.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J et al. . Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA 2006; 296:782–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coetzee D, Hildebrand K, Boulle A et al. . Outcomes after two years of providing antiretroviral treatment in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS 2004; 18:887–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bussmann H, Wester CW, Ndwapi N et al. . Five-year outcomes of initial patients treated in Botswana’s National Antiretroviral Treatment Program. AIDS 2008; 22:2303–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Progress Report. Global Health Sector Response to HIV, 2000–2015. Focus on Innovations in Africa. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Fact Sheet - 2030 Ending the AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: United Nations; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grimsrud A, Balkan S, Casas EC et al. . Outcomes of antiretroviral therapy over a 10-year period of expansion: a multicohort analysis of African and Asian HIV programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 67:e55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elul B, Saito S, Chung H et al. . Attrition from human immunodeficiency virus treatment programs in Africa: a longitudinal ecological analysis using data from 307 144 patients initiating antiretroviral therapy between 2005 and 2010. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:1309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The TenoRes Study Group. Global epidemiology of drug resistance after failure of WHO recommended first-line regimens for adult HIV-1 infection: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:565–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boender TS, Hoenderboom BM, Sigaloff KC et al. . Pretreatment HIV drug resistance increases regimen switches in sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1749–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization. Progress Report 2016. Prevent HIV, Test and Treat All. Geneva: World Health Orgaization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Siedner MJ, Ng CK, Bassett IV et al. . Trends in CD4 count at presentation to care and treatment initiation in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2002–2013: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1120–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2016. Geneva: World Health Orgaization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gupta-Wright A, Wood R, Bekker LG, Lawn SD. Temporal association between incident tuberculosis and poor virological outcomes in a South African antiretroviral treatment service. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 64:261–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pacheco AG, Veloso VG, Nunes EP et al. . Tuberculosis is associated with non-tuberculosis-related deaths among HIV/AIDS patients in Rio de Janeiro. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18:1473–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bassett IV, Wang B, Chetty S et al. . Intensive tuberculosis screening for HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51:823–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization. Systematic Screening for Active Tuberculosis: Principles and Recommendations.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reepalu A, Balcha TT, Skogmar S et al. . High rates of virological suppression in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus-positive adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in ethiopian health centers irrespective of concomitant tuberculosis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2014; doi:10.1093/ofid/ofu039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health. Guidelines for Clinical and Programmatic Management of TB, Leprosy and TB/HIV in Ethiopia.Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health. National Guidelines for Comprehensive HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Balcha TT, Sturegård E, Winqvist N et al. . Intensified tuberculosis case-finding in HIV-positive adults managed at Ethiopian health centers: diagnostic yield of Xpert MTB/RIF compared with smear microscopy and liquid culture. PLoS One 2014; 9:e85478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boender TS, Sigaloff KC, McMahon JH et al. . Long-term virological outcomes of first-line antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1453–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bastard M, Nicolay N, Szumilin E et al. . Adults receiving HIV care before the start of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: patient outcomes and associated risk factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 64:455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta A, Wood R, Kaplan R et al. . Prevalent and incident tuberculosis are independent risk factors for mortality among patients accessing antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. PLoS One 2013; 8:e55824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soeters HM, Napravnik S, Patel MR et al. . The effect of tuberculosis treatment on virologic and CD4+ cell count response to combination antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review. AIDS 2014; 28:245–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoffmann CJ, Charalambous S, Sim J et al. . Viremia, resuppression, and time to resistance in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) subtype C during first-line antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:1928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boender TS, Kityo CM, Boerma RS et al. . Accumulation of HIV-1 drug resistance after continued virological failure on first-line ART in adults and children in sub-Saharan Africa. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71:2918–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grennan JT, Loutfy MR, Su D et al. ; CANOC Collaboration Magnitude of virologic blips is associated with a higher risk for virologic rebound in HIV-infected individuals: a recurrent events analysis. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:1230–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boulle A, Van Cutsem G, Hilderbrand K et al. . Seven-year experience of a primary care antiretroviral treatment programme in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS 2010; 24:563–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rohr JK, Ive P, Horsburgh CR et al. . Developing a predictive risk model for first-line antiretroviral therapy failure in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barth RE, Tempelman HA, Moraba R, Hoepelman AI. Long-term outcome of an HIV-treatment programme in rural africa: viral suppression despite early mortality. AIDS Res Treat 2011; 2011:434375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Druyts E, Dybul M, Kanters S et al. . Male sex and the risk of mortality among individuals enrolled in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2013; 27:417–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cornell M, Schomaker M, Garone DB et al. ; International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS Southern Africa Collaboration Gender differences in survival among adult patients starting antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a multicentre cohort study. PLoS Med 2012; 9:e1001304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu E, Spiegelman D, Semu H et al. . Nutritional status and mortality among HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. J Infect Dis 2011; 204:282–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cox JA, Lukande RL, Nelson AM et al. . An autopsy study describing causes of death and comparing clinico-pathological findings among hospitalized patients in Kampala, Uganda. PLoS One 2012; 7:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bates M, Mudenda V, Shibemba A et al. . Burden of tuberculosis at post mortem in inpatients at a tertiary referral centre in sub-Saharan Africa: a prospective descriptive autopsy study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:544–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cornell M, Lessells R, Fox MP et al. ; IeDEA-Southern Africa Collaboration Mortality among adults transferred and lost to follow-up from antiretroviral therapy programmes in South Africa: a multicenter cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 67:e67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cingolani A, Cozzi Lepri A, Castagna A et al. . Impaired CD4 T-cell count response to combined antiretroviral therapy in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected patients presenting with tuberculosis as AIDS-defining condition. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:853–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Skogmar S, Schön T, Balcha TT et al. . CD4 cell levels during treatment for tuberculosis (TB) in Ethiopian adults and clinical markers associated with CD4 lymphocytopenia. PLoS One 2013; 8:e83270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Machekano R, Bassett M, McFarland W, Katzenstein D. Clinical signs and symptoms in the assessment of immunodeficiency in men with subtype C HIV infection in Harare, Zimbabwe. HIV Clin Trials 2002; 3:148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bassett IV, Chetty S, Wang B et al. . Loss to follow-up and mortality among HIV-infected people co-infected with TB at ART initiation in Durban, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 59:25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.