Abstract

Access to Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) care has not been explored among older racial/ethnic minorities. We used data on adults 55-years and older from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (2008–2013). We account for five features of PCMH experiences and focus on respondents self-identifying as Non-Latino White, Black, and Latino. We used regression models to examine associations between PCMH care and its domains and race/ethnicity and decomposition techniques to assess contribution to differences by predisposing, enabling and health need factors. We found low overall access and significant racial/ethnic variations in experiences of PCMH. Our results indicated strong deficiencies in access to a personal primary care physician provided healthcare. Factors contributing to differences in reported PCMH experiences relative to Whites differed by racial/ethnic grouping. Policy initiatives aimed at addressing accessibility to personal physician directed healthcare could potentially reduce racial/ethnic differences while increasing national access to PCMH care.

Keywords: Racial/ethnic disparities, Healthcare quality, Primary care, PCMH

Introduction

In recent years the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) has emerged as a promising model for improving primary care delivery in the U.S. [1, 2]. Under the PCMH model, each patient has a personal primary care physician who directs a team of healthcare professionals in order to provide comprehensive, accessible, patient-centered, and coordinated care to that patient, with an emphasis on quality and care safety, for the purpose of maximizing the patient’s health outcomes [3, 4]. The PCMH model for primary care delivery has earned the support of a full range of healthcare stakeholders, including every major physician organization in the U.S., major consumer groups, and most Fortune 500 companies [5]. It is also increasingly being adopted nationally, e.g., between 2009 and 2013 the number of patients nationwide covered by PCMH initiatives increased fourfold, to nearly 21 million by 2013 [6].

Recent studies suggest that healthcare consistent with PCMH principles improves patient and staff experiences, care quality, and patients’ use of preventive services [7]. Yet, there is a gaping absence of research on whether vulnerable racial/ethnic minority populations, such as older Blacks and Latinos, have similar access to care consistent with PCMH principles, compared to their non-Latino White (hereafter called Whites) counterparts.

To address current gaps in knowledge about PCMH access among near-old and older ethnic/racial minority adults, we used nationally representative data from the 2008–2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). We assessed racial and ethnic differences in access to PCMH-like care and examined the determinants of group differences. We followed a modified Andersen’s Behavioral Model of healthcare access and utilization to guide our investigative approach [8, 9].

Methods

Data

We used the nationally representative MEPS full year consolidated data files from 2008 to 2013. Each year MEPS collects data on respondents’ use of health services, their health status and specific medical conditions, experiences with care at their physician’s office, satisfaction with care, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, and other data, as well. Details regarding survey response rates, the questionnaire, and a description of its survey design are provided elsewhere [10, 11].

The sample consisted of 19,589 adults, ages 55 years and older, who self-reported being White, Black, or Latino, and who reported having a visit to their doctor during the past 12-months. Native Americans, Asians, and other minority groups were excluded from our analysis because of their small sample counts in MEPS. There were 13,221 Whites, 3581 Blacks, and 2787 Latinos in our sample.

Our decision to include both near-old (55–64 years) and older adults is based on four considerations. First, overall, near-old adults have increasingly high healthcare needs and this is an age range when many chronic conditions often begin to emerge [12]. Second, minorities in this age group are at higher risk for disease and disability and as such would especially benefit from innovative healthcare models such as the PCMH. Third, African Americans have much lower life expectancy compared to non-Latino Whites and as such including near-old African Americans in the analyses captures respondents with health risks and disease profiles who have a lower probability of survival past the age of 65. Including this group in the analyses can help inform policies geared towards improving their healthcare access to innovative and promising healthcare models that can have important implications for their health and life expectancy. Excluding near-old adults risks focusing the analyses on a more select group of older Blacks who are resilient and more likely to survive into older age. Fourth, a more pragmatic consideration was to increase sample size and avoid the prospect of low power that could result from age stratified analyses. This is particularly important since the aim of the work is to compare minorities (Blacks and Hispanics) to non-Hispanic Whites. That said, and to ensure robustness of our findings, we have conducted additional work to explore deviations from our conclusions resulting from such stratified analyses. This sensitivity check showed that our results and conclusions were both quantitatively and qualitatively robust and similar findings were derived from the stratified analyses.

Primary Outcome

Our primary outcome was a (0, 1) indicator for whether the respondent was receiving care consistent with PCMH principles. This indicator was constructed from an individual’s answers to 17 questions in MEPS regarding whether the individual had a usual source of care, and if so, their experiences with that care. Similar questions have been previously used by other researchers to identify access to PCMH care [13–20]. Table 1 describes the algorithm used to construct our five PCMH features (1) a usual and personal primary care physician (generalist/internist/family medicine), (2) enhanced access to the physician, (3) patient-focused care, (4) comprehensive care, and (5) compassionate care) as well as our PCMH experiences construct. We did not include measures of coordination in the operationalization of the PCMH construct. Available MEPS data showed trivial variations in these measures overall and across different groups. The reported rates for “going to a provider for new health problems”, “going to a provider for preventive healthcare”, “going to a provider for referrals”, and “going to a provider for ongoing health problems” were 98.5, 98.3, 97.5, and 97.9 %, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) experience underlying measures, features, and scoring criteria applied to the medical expenditures panel survey (2008–2013) data

| Feature measure | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Personal primary care provider | |

| Usual source of care (yes) & personal provider (person or person in facility) & specialty (family or internal medicine) | Yes (all three conditions satisfied) |

| Enhanced access | |

| Ease of after hours access (0 = not at all; 25 = not too much; 75 = somewhat; 100 = very) | Yes (average score ≥75) |

| Ease of getting to provider (0 = not at all; 25 = not too much; 75 = somewhat; 100 = very) | |

| Ease of contacting provider by phone (0 = not at all; 25 = not too much; 75 = somewhat; 100 = very) | |

| Patient-focused | |

| Doctor asked person to help in decision (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | Yes (average score ≥75) |

| Doctor showed respect for other treatment options (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | |

| Doctor discussed options (0 = no; 100 = yes) | |

| Comprehensive | |

| Ease of getting immediate care when needed (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | Yes (average score ≥75) |

| Ease of getting appointment when needed (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | |

| Ease of getting specialist referrals when needed (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | |

| Ease of getting tests and treatments when needed (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | |

| Compassionate | |

| Doctor listened (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | Yes (average score ≥75) |

| Doctor spent enough time (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | |

| Doctor explained things (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | |

| Doctor showed respect (0 = never; 25 = sometimes; 75 = usually; 100 = always) | |

| PCMH care | |

| Personal primary care provider, enhanced access, patient focused, comprehensive and compassionate | Yes (criteria for all five domains satisfied) |

We followed previous published work in operationalizing the PCMH [16, 17]. We created an average score for each dimension by summing each respondent’s item scores as specified in Table 1 and dividing by the total number of non-missing items. An average score of 75 or more was coded as satisfying PCMH criteria for the considered domain. Next, we created a two-category PCMH indicator. Individuals satisfying PCMH criteria for all five domains were coded as having a PCMH. More specifically, to qualify as having a PCMH, a respondent had to report having a usual source of care that is a person (as opposed to a facility) and that is not a specialist. In addition, a respondent had to have an average score of 75 or more on each of the composite constructs. All other respondents reporting a USC but not satisfying all 5 PCMH criteria were coded as having USC but no PCMH. To see if our results were sensitive to the way we operationalized having PCMH-like care, additional analyses were done using the number of satisfied criteria as a continuous main predictor. The results were qualitatively equivalent.

Covariates

In line with the modified Andersen behavioral model of healthcare access, each of these estimated models accounted for the effects of predisposing, enabling and need factors [8, 9]. Our primary predictor was race/ethnicity (White, Black, or Latino). Predisposing factors included age in years, sex, and a MEPS staff-generated measure of household income relative to the federal poverty threshold (<100, 100–124, 125–199, 200–399 and 400 % or more). Enabling factors consisted of education (less than high school, high school, some college, college or more), predominant home language (English, Other), and health insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, Medicare and Medicaid, other public, private, or uninsured). Insurance groupings were based on reports of coverage under a certain program during any time of the year. A person was considered uninsured if they reported being uninsured all year. Health Needs were measured using a dichotomous self-rated health status measure (poor/fair or good/very good/excellent), a summary index of overall physical functioning (SF-12 Physical) [21, 22], and mental health (SF-12 mental) [21, 22], and an index of chronic conditions created using self-reports for the presence of ten major health conditions including angina, asthma, coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, reporting having a heart attack or other heart conditions, stroke, emphysema, and joint pain (range 0–10) [23]. Finally, we accounted for US region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West) and the survey year, with 2008 as the reference year.

Analysis

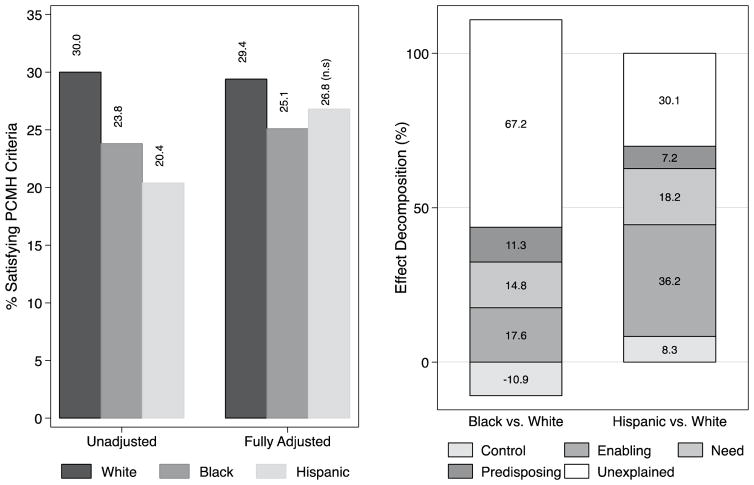

Analyses proceeded in four steps. First, we computed sample descriptive statistics for each of our three racial/ethnic groups, and tested for differences in population characteristics across groups using standard F-tests (Table 2). Second, we estimated the prevalence of access to PCMH-like care and access to each of its features. We used survey-adjusted Chi square tests to assess whether access among near-old and older Blacks or Latinos differed from access among Whites (Table 3). Third, we estimated multivariate logit regressions to quantify the determinants of access to PCMH-like care and access to its features, adjusting for the covariates described above. From the estimated models we calculated the adjusted marginal effects of race and ethnicity to translate the coefficient estimates into interpretable prevalence rates for each racial/ethnic group. We then tested whether access among older Blacks or Latinos differed from access among older Whites (Table 3). The estimated odds-ratios from this analysis are graphically summarized in Supplemental Fig. 1 (also see supplemental Table 1). Finally, we used regression decomposition methods, based on a modified Blinder-Oaxaca technique for binary outcomes [24, 25], to allocate the contribution of the regression model’s predisposing, enabling, and need-related variables in accounting for the observed differences in access to PCMH-like care between older Blacks and Whites, and between older Latinos and Whites (Fig. 1). These decompositions quantify the degree to which distributional differences for the model’s covariates across racial/ethnic groups explain the observed differences in access. We also quantify the part of the difference in access that remained unexplained by the covariates, also referred to as differences in coefficients, which are attributable to group-specific characteristics that the estimated models did not account for (e.g., mistrust of providers, discrimination, neighborhood characteristics, etc).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of United States adults 55-years and older reporting at least one visit to the doctor during the past 12-months by racial/ethnicity

| White | Black | Latino | F test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %/Mean | %/Mean | %/Mean | ||

| Predisposing | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 55.0 | 60.4 | 58.0 | p = 0.0000 |

| Male | 45.0 | 39.6 | 42.0 | |

| Age (years) | 67.6 | 66.3 | 66.8 | p = 0.0000 |

| Household incomea | ||||

| Poor | 6.9 | 18.0 | 17.8 | p = 0.0000 |

| Near poor | 6.9 | 18.0 | 17.8 | |

| Low income | 12.1 | 18.7 | 21.8 | |

| Middle income | 27.6 | 28.2 | 28.9 | |

| High income | 49.4 | 26.8 | 24.0 | |

| Enabling | ||||

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 25.6 | 24.4 | 24.4 | p = 0.0000 |

| Medicaid | 1.3 | 5.2 | 6.6 | |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 3.5 | 14.0 | 21.6 | |

| Other | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.3 | |

| Private | 66.0 | 49.0 | 38.0 | |

| Uninsured | 2.8 | 5.8 | 8.0 | |

| Education | ||||

| Less than HS | 9.9 | 24.9 | 49.7 | p = 0.0000 |

| HS or equivalent | 32.1 | 34.2 | 21.4 | |

| Some college | 21.1 | 20.7 | 13.4 | |

| College or more | 36.9 | 20.3 | 15.5 | |

| Language | ||||

| Other | 1.0 | 1.6 | 56.8 | p = 0.0000 |

| English | 99.0 | 98.4 | 43.2 | |

| Healthcare need | ||||

| Self reported health | ||||

| Excellent/good/very good | 81.3 | 70.0 | 63.2 | p = 0.0000 |

| Fair/poor | 18.7 | 30.0 | 36.8 | |

| Mental SF-12b | 52.1 | 50.8 | 48.6 | p = 0.0000 |

| Physical SF-12b | 43.4 | 40.8 | 41.6 | p = 0.0000 |

| Number of conditions | 2.8 | 3.1 | 2.7 | p = 0.0000 |

| Controls | ||||

| US Region | ||||

| Northeast | 19.9 | 16.9 | 17.5 | p = 0.0000 |

| Midwest | 25.3 | 16.3 | 7.6 | |

| South | 35.3 | 58.0 | 36.7 | |

| West | 19.5 | 8.8 | 38.2 | |

Results are from the medical expenditures panel survey (2008–2013) data

Using the physical and mental components of the 12-item short-form health survey

Using a MEPS staff-generated measure of household income relative to the federal poverty threshold (poor = <100 %, near poor = 100–124 %, low income = 125–199 %,

middle income = 200–399 %, and high income = 400 % or more)

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted (predisposing, enabling, and need factors) prevalence of PCMH-like care and its features by race and ethnicity among United States adults 55-years and older reporting at least one visit to the doctor during the past 12-months in the medical expenditures panel survey (2008–2013)

| Unadjusteda | Adjusteda | |

|---|---|---|

| % [95 % CI] | % [95 % CI] | |

| Personal primary care provider | ||

| White | 56.4 [54; 58.9] | 56.1 [53.6; 58.6] |

| Black | 51.4** [48.5; 54.4] | 50.9*** [47.9; 53.9] |

| Latino | 47.7*** [45.1; 50.2] | 50.7* [46.9; 54.5] |

| Enhanced access | ||

| White | 73.9 [72.7; 75] | 73.1 [71.9; 74.4] |

| Black | 70.6** [68.9; 72.4] | 73.4 (ns) [71.7; 75.2] |

| Latino | 66.5*** [64.2; 68.8] | 75 (ns) [71.7; 78.4] |

| Patient-focused | ||

| White | 83.5 [82.5; 84.5] | 83.5 [82.4; 84.5] |

| Black | 82.2 (ns) [80.6; 83.8] | 83.0 (ns) [81.5; 84.6] |

| Latino | 80.2** [77.9; 82.5] | 82.9 (ns) [80.2; 85.5] |

| Comprehensive | ||

| White | 88.0 [87.4; 88.7] | 87.6 [86.9; 88.2] |

| Black | 83.4*** [82; 84.7] | 85.2*** [83.8; 86.5] |

| Latino | 79.5*** [77.8; 81.2] | 84.6** [82.5; 86.7] |

| Compassionate | ||

| White | 89.7 [89.1; 90.3] | 89.1 [88.4; 89.8] |

| Black | 87.4*** [86.3; 88.4] | 88.9 (ns) [87.8; 90.1] |

| Latino | 87.8** [86.3; 89.2] | 91.2* [89.5; 92.9] |

A detailed list of features and their underlying measures and scoring algorithm is provided in Table 1

Estimates are based on results from logistic regression models (available from the authors upon request). Adjusted models include sex, age, household income, insurance, education, language, self-reported health status, mental SF-12, physical SF-12, number of chronic medical conditions, region, and survey year

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001, ns = P > 0.05

Fig. 1.

Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence of PCMH-like care experiences by race and ethnicity, and the determinants of minority group differences relative to Whites. Results are based on logistic regression models and Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of data on United States adults 55-years and older reporting at least one visit to the doctor during the past 12-months from the 2008–2013 MEPS. Note 1: Prevalence estimates are based on logistic regression models (available from the authors upon request). Note 2: U = Unadjusted (crude), Fully adjusted = Adjusted for predisposing (sex, age, household income), enabling (insurance, education, language), health need (self-reported health status, mental SF-12, physical SF-12, number of chronic medical conditions), factors and controls (region, and survey year). Note 3: Effect decomposition are based on non-linear Oaxaca-Blinder techniques. Bars included in the negative quadrant of the graph represent factors that contribute to higher access among racial/ethnic minority groups. Bars included in the positive quadrant of the graph represent factors that would enhance access among racial/ethnic minorities. The width of each bar represents the percentage of between group difference (e.g. Black vs. White) in the probability of access to PCMH-like care explained by the factors or, more specifically, the expected change in difference if both groups had similar characteristics. The sum of the positive (including unexplained) and negative contributors add up to 100 % of the difference between the compared groups

All results were based on chained multiple imputations used to generate ten complete analytic data sets [26]. All estimated parameters and inferences incorporated these ten data sets and followed modeling recommendations that have been extensively discussed elsewhere [26–29]. Additionally, complex survey data procedures, more specifically a Taylor Series Linearization approach, and probability weighting in the Stata software package 13.1 were used to adjust for the complex design of the MEPS [25].

Results

Differences in Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors (Table 2)

Near-old and older minorities were more likely to be female, report household income below 200 % of the federal poverty level, and were younger, on average, compared to Whites. Blacks were more likely to reside in the South and Latinos more likely to reside in the West.

Near-old and older minorities, particularly Latinos, were more likely to report having less than a high school education, and they more often reported being uninsured or having Medicaid as a source of insurance. Latinos were much less likely than the other groups to report English as their predominant home language. Minorities also more often reported fair/poor health, and had lower scores, on average, on the mental and physical SF12 scales. Blacks reported slightly more health conditions than Whites and Latinos.

Differences in Access

The unadjusted and adjusted overall rates of access to PCMH features are reported in Table 3, and Supplemental Fig. 1 presents the unadjusted and fully adjusted odds ratios of access relative to Whites. Access was highest for compassionate care (87.8–89.7 %). Next most common was care that was comprehensive (79.5–88.0 %), care that was patient-focused (80.2–83.5 %), enhanced access (66.5–73.9 %), and personal primary care (47.7–56.4 %). On most measures of access, older Whites had the highest level of access while Latinos had the lowest.

The unadjusted estimates revealed that, with the exception of patient focused care among Blacks, near-old and older Blacks and Latinos consistently had significantly lower odds of having each key feature of PCMH care. Specifically, the unadjusted rate of having a personal primary care physician among Blacks and Latinos was 8.9 and 15.5 % lower than the 56.4 % reported among Whites. Blacks and Latinos were also 4.5 and 10 %, respectively, less likely to report enhanced access to care compared to Whites (73.9 %). Near-old and older Latinos had 4 % lower access to patient-focused care compared to older Whites (83.5 %). They also reported 5.3 and 9.7 % lower access to comprehensive care compared to Whites (88.0 %). Finally, Blacks and Latinos were 2.6 and 2.1 %, respectively, less likely to report access to compassionate care compared to Whites (89.7 %).

Adjusting for the predisposing, enabling and need factors of the behavioral model completely eliminated several of these observed differences in access for near-old and older Blacks and Latinos. Specifically, the adjusted estimates suggest there were no differences in the receipt of enhanced access and compassionate care between Blacks and Whites. The adjusted estimates also attenuated differences between Latinos and Whites with respect to access to a personal primary care physician, enhanced access, patient focused, and comprehensive care, and near-old and older Latinos had higher reported prevalence of compassionate care.

Differences in Access to PCMH-Like Care

The expected unadjusted and adjusted rates of access are presented in Fig. 1. Unadjusted estimates show that slightly more than three in ten near-old and older Whites (30.0 %) satisfied the criteria for having PCMH-like care. Blacks (23.8 %) and Latinos (20.4 %) were 20.7 and 32.2 % less likely to satisfy criteria for having PCMH-like care. Adjusting for factors in the Behavioral model only slightly reduced the relative difference in reported access between near-old and older Blacks and Whites to 14.6 %. However, the difference between older Latinos and Whites was completely attenuated by the model adjustments.

Determinants of Difference in Access to PCMH-Like Care

Figure 1 also includes the results of the non-linear decomposition of differences in access across groups. Of the estimated difference in rates of access to PCMH-like care between near-old and older Blacks and Whites, the enabling, need-related, and predisposing factors in the estimated logit model explained 17.6, 14.8, and 11.3 %, respectively, of the difference, but the geographic residence of Black respondents (i.e., regional differences) and survey year presented an 11 % advantage in rates of access relative to Whites. Still, 67.2 % of the overall difference in rates of access to PCMHlike care remained unexplained by factors accounted for in our model.

In sharp contrast, our model explained most of the difference in rates of access to PCMH-like care between nearold and older Latinos and Whites. Enabling factors, namely education, language, and health insurance, explained 36.2 % of the differences between Latinos and Whites, and close to 18.2 % was explained by need factors. Only 30.0 % of the difference in rates remained unexplained by factors not accounted for in our model.

Discussion

Three major finding emerged from our study of PCMH access among near-old and older ethnic/racial minorities between years 2008–2013. First, the large majority of adults ages 55 and older nationwide are not receiving PCMH-like care. Only slightly more than one-in-four report healthcare experiences consistent with the principles of PCMH care. Second, we found significant ethnic/racial differences in access to PCMH-like healthcare. Additionally, we found disparate levels in access to several key PCHM healthcare features. For example, both Blacks and Latinos had significantly less access than Whites to personal primary healthcare providers, enhanced access to care, care that is patient-focused, comprehensive, and compassionate. Third, the specific determinants of reduced access relative to Whites differed for near-old and older Blacks and Latinos. For example, enabling factors, such as health insurance, language, and level of education, are central in explaining differences in access between Latinos and Whites, but to a much lesser degree for Blacks and Whites.

Despite widespread and growing support for PCMH, our findings demonstrated that most near-old and older adults currently lack access to PCMH-like care, especially among Blacks and Latinos relative to Whites. This suggests that for the PCMH model to become a viable model nationwide for near-old and older adults, an important developmental period when healthcare need increases, a substantial increased effort is required to reorient and refocus the US health system on delivery of primary care, and to transform patient primary care practice experiences for all Americans. Our findings also show that having access to a personal primary care provider as a usual source of care is currently the biggest barrier to the growth of PCMH-like care, particularly among near-old and older Blacks and Latinos. Thus, increasing access to a personal primary care provider should be a primary objective of healthcare policy initiatives. Arguments within the PCMH literature have also advanced the importance of networks (e.g. “Medical Neighborhood”) as a way to break the “siloed” nature of healthcare in the US and achieve the policy goals of more equitable, better quality, and cost efficient healthcare [30, 31]. These models, borrowing from organizational theory, emphasize the infrastructure and tools for strengthening the coordination between care providers, disciplines, and organizations as critical to achieving the PCMH goals [30]. Team-Based healthcare models can be particularly useful for complex patients (e.g. cardiovascular comorbidities) likely to be found in aged populations [32]. Health plans, managed care organizations, and health systems across the US are pursuing infrastructure transformation and system upgrades (e.g. payment models) to adopt and integrate PCMH characteristics [33]. Recent work has also argued for transforming community health centers into PCMHs [34], and shown that such transformations can be critical for enhancing healthcare quality in underserved populations [35, 36]. This said, the PCMH remains decisively a primary care model and [37], as such, the primary care physician remains an anchoring force for achieving the equity enhancement, quality improvements, and cost reductions that are increasingly needed under the specialization heavy US health care system.

In our current healthcare environment, increasing access to primary care providers is likely to prove difficult. The demand for healthcare, generally, is likely to rise substantially over the next decade as a result of population growth, the expansion of health insurance occurring under the Affordable Care Act, and population aging [38]. Yet recent trends indicate that fewer medical students are choosing primary care specialties, and among those who are choosing them many are going into subspecialties [39]. These trends could hamper efforts to reform the primary care system and realign healthcare in the US with a more efficient clinical care model. Other barriers also continue to play important roles in determining access to primary care including clinic low capacity resulting from downward trends in hours served, increased part time services by physicians, a paucity of primary care clinics, especially in disadvantaged, low income neighborhoods, and difficulty accessing providers after-hours and on weekends [40–43].

Our results also indicate that despite decades of public health efforts and policy interventions, near-old and older Blacks and Latinos continue to report less satisfying care experiences in several respects, compared to older Whites. Older minorities are less likely to have enhanced access to care and comprehensive and compassionate care. Latinos also reported lower levels of patient-focused care. These results are consistent with previous work that provides evidence of more limited access to extended hours of care [44], longer distances traveled to obtain care, as well as higher burden among minorities in getting timely [45], comprehensive and coordinated care. Our findings also complement earlier studies that document negative associations between race/ethnicity patient centeredness of care [46], positive provider style [47, 48] (e.g., provision of compassionate and respectful care) [49], quality and clarity of patient-provider communication [49–51], patient satisfaction with involvement in the care process [52], patient satisfaction with decisions and the decision making progress [51, 53, 54], as well as overall perception of the care experience [55, 56]. Most important, the lower prevalence of access to these combined elements of care quality as seen in our PCMH experiences indicator shows that a successful implementation of clinic and provider transformation will require strategies that simultaneously target multiple domains of care. Such efforts might prove more difficult and costly to implement especially in practices serving underserved communities, and if not accompanied with sizeable incentives might face resistance from an already overburdened primary care workforce.

Third, our findings of ethnic/racial disparities in accordance with Institute of Medicine’s criteria [57] and consistent with previous reports [58, 59] indicate that differences in healthcare needs only partially explain differences in access to high-quality PCMH. Furthermore, we observed ethnic/racial variation in access that could inform successful group-specific solutions efforts and policies. Enabling factors, such as healthcare insurance, language, and education explained the plurality of the uncovered differences between Latinos and Whites. As such, modifiable policy targets like the newly established insurance mandates and incentives for public health programs that increase awareness about primary care and provide incentives for higher quality in provider care can substantially reduce differences between Latinos and Whites. Our findings suggest that such interventions might have less impact among Blacks since enabling factors were only partially responsible for differences in PCMH access, which leaves most of the differences unexplained of the difference remained uncaptured by our model covariates [60]. Research suggests that contextual barriers (e.g. racial segregation) and the selective nature of physicians providing care to Blacks contribute to these differences [61–63]. Supply-side policy interventions that encourage primary care providers to locate into racially segregated areas, and current providers to accept under-served patients (e.g. Medicaid) might help reduce differences between African Americans and Whites.

There were several study limitations that should be mentioned. First, self-reported survey data may be susceptible to reporting biases that could have affected our estimates. However, sensitivity studies conducted on the MEPS data has shown good overall response validity [64]. Second, the MEPS underestimates national expenditures as reported by the actuarial office and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services [65, 66]. Third, our findings could potentially be sensitive to the way we operationalized the PCMH domains. We are aware of the recommendations of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) on the best strategies and possible pitfalls of working with the PCMH. We recognize that the PCMH is a practice-level model, and acknowledge that our operationalization of having PCMH-like care uses respondents’ assessments of the care they received as proxies for physician practice capabilities. Indeed, we emphasized that our PCMH-like construct was based on respondents assessment. Consequently, bias could result from individual assessments which are subject to personal biases that are informed by factors exogenous to a physician practice’s characteristics including the patient’s demographic, socio-economic and health characteristics. Fourth, our insurance groups were based on coverage under a certain program (e.g. Medicare) at any time during the year and do not account for different spells of coverage under different policies or the length/duration of coverage by a particular program. Future research should consider how more detailed accounting of such spells and different insurance plan mixtures relate to access to a PCMH, and how such mixtures contribute to explaining differences between minorities and non-Latino Whites. Finally, the MEPS does not allow us to account for contextual measures such as neighborhood characteristics or to link respondents to primary care coverage areas. Statements we made in the discussion about the possible contribution of these factors are hypothetical and require further research.

Conclusion

Most near-old and older adults (ages 55 and older) in the US do not receive PCMH-like healthcare, and access to a personal primary care provider is a main obstacle. Furthermore, marked ethnic/racial disparities in PCMH-like healthcare access persist. Our study demonstrated that ethnically/racially tailored and targeted healthcare policy interventions may be effective in reducing PCMH-like healthcare access disparities relative to Whites among near-old and older Blacks and Latinos.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by National Institute on Aging (Grant No. P30 AG015281).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10903-016-0491-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Larson EB, Reid R. The patient-centered medical home movement. JAMA. 2010;303(16):1644–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis K, Abrams M, Stremikis K. How the Affordable Care Act will strengthen the nation’s primary care foundation. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1201–3. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AAFP, AAP, ACP, AOA. Joint Principles of the Patient Centered Medical Home. [Accessed 21 Jan 2007];Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative. 2013 http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/delivery_and_payment_models/pcmh/demonstrations/jointprinc_05_17.pdf.

- 4.Burton RA. Patient-centered medical home recognition tools: a Comparison of ten surveys’ content and operational details. Washington DC: Urban Insitute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: will it stand the test of health reform? JAMA. 2009;301(19):2038–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards ST, Bitton A, Hong J, Landon BE. Patient-centered medical home initiatives expanded in 2009–13: providers, patients, and payment incentives increased. Health Aff. 2014;33(10):1823–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, et al. The patient-centered medical home: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):169–78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4) (online-only) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed 31 Jul 2014];MEPS-HC response rates by panel. 2014 http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/hc_response_rate.jsp.

- 11.Ezzati-Rice T, Rohde F, Greenblatt J. Sample design of the medical expenditure panel survey household component, 1998–2007. Methodol Rep. 2008:22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Health, United States, 2011: with special feature on socioeconomic status and health. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beal A, Hernandez S, Doty M. Latino access to the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):514–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1119-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bethell CD, Read D, Brockwood K. Using existing population-based data sets to measure the American Academy of Pediatrics definition of medical home for all children and children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 Suppl):1529–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romaire MA, Bell JF, Grossman DC. Health care use and expenditures associated with access to the medical home for children and youth. Med Care. 2012;50(3):262–69. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318244d345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romaire MA, Bell JF, Grossman DC. Medical home access and health care use and expenditures among children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(4):323–30. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romaire MA, Bell JF. The medical home, preventive care screenings, and counseling for children: evidence from the medical expenditure panel survey. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(5):338–45. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aysola J, Orav EJ, Ayanian JZ. Neighborhood characteristics associated with access to patient-centered medical homes for children. Health Aff. 2011;30(11):2080–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strickland BB, Jones JR, Ghandour RM, Kogan MD, Newacheck PW. The medical home: health care access and impact for children and youth in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):604–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strickland B, McPherson M, Weissman G, van Dyck P, Huang ZJ, Newacheck P. Access to the medical home: results of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 Suppl):1485–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker D, Gandek B. SF-12v2: how to score version 2 of the SF-12 health survey quality metric incorporated. Massachusetts: Health Assessment Lab Boston; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorpe K, Florence C, Joski P. Which medical conditions account for the rise in health care spending? Health Aff. 2004;23(Suppl 2):437–45. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yun M-S. Decomposing differences in the first moment. Econ Lett. 2004;82(2):275–80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jann B. The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata. 2008;8(4):453–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royston P, White IR. Multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE): implementation in Stata. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(4):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 27.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–99. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, Leaf PJ. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(1):40–9. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchenko YV, Eddings W. A note on how to perform multiple-imputation diagnostics in Stata. College Station: StataCorp; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alidina S, Rosenthal M, Schneider E, Singer S. Coordination within medical neighborhoods: insights from the early experiences of Colorado patient-centered medical homes. Health Care Manage Rev. 2016;41(2):101–12. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart E, Jaen C. Transforming physician practices to patient-centered medical homes: lessons from the national demonstration project. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(3):439–45. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipton HL. Home is where the health is: advancing teambased care in chronic disease management. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1945. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bitton A, Martin C, Landon BE. A nationwide survey of patient centered medical home demonstration projects. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):584–92. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1262-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson DR, Olayiwola JN. Community health centers and the patient-centered medical home: challenges and opportunities to reduce health care disparities in America. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(3):949–57. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cook N, Hollar L, Isaac E, Paul L, Amofah A, Shi L. Patient experience in health center medical homes. J Community Health. 2015;40(6):1155–64. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lebrun-Harris LA, Shi L, Zhu J, Burke MT, Sripipatana A, Ngo-Metzger Q. Effects of patient-centered medical home attributes on patients’ perceptions of quality in federally supported health centers. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(6):508–16. doi: 10.1370/afm.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed 20 Jun 2016];Defining the PCMH. 2016 https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

- 38.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010–2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeffe DB, Whelan AJ, Andriole DA. Primary care specialty choices of United States medical graduates, 1997–2006. Acad Med. 2010;85(6):947–58. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dbe77d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berry-Millett R. The health care problem no one’s talking about. J Fam Pract. 2009;58(12):633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):799–805. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Trends in the work hours of physicians in the united states. JAMA. 2010;303(8):747–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor SL, Lurie N. The role of culturally competent communication in reducing ethnic and racial healthcare disparities. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(Spec No):SP1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Malley AS. After-hours access to primary care practices linked with lower emergency department use and less unmet medical need. Health Aff. 2013;32(1):175–83. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taira DA, Safran DG, Seto TB, et al. Do patient assessments of primary care differ by patient ethnicity? Health Serv Res. 2001;36(6 Pt 1):1059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beach MC, Saha S, Korthuis PT, et al. Differences in patient-provider communication for Hispanic compared to non-Hispanic white patients in HIV care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):682–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doescher MP, Saver BG, Franks P, Fiscella K. Racial and ethnic disparities in perceptions of physician style and trust. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(10):1156–63. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halbert CH, Armstrong K, Gandy OH, Shaker L. Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8):896–901. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nápoles AM, Gregorich SE, Santoyo-Olsson J, O’Brien H, Stewart AL. Interpersonal processes of care and patient satisfaction: do associations differ by race, ethnicity, and language? Health Serv Res. 2009;44(4):1326–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beach M, Saha S, Korthuis PT, et al. Patient-provider communication Differs for black compared to white hiv-infected patients. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):805–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1713–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gordon HS, Street RL, Sharf BF, Souchek J. Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer. 2006;107(6):1313–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mead EL, Doorenbos AZ, Javid SH, et al. Shared decision-making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):e15–e29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeVoe JE, Wallace LS, Pandhi N, Solotaroff R, Fryer GE., Jr Comprehending care in a medical home: a usual source of care and patient perceptions about healthcare communication. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):441. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.080054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–90. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chou W-YS, Wang LC, Finney Rutten LJ, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Factors associated with Americans’ ratings of health care quality: what do they tell us about the raters and the health care system? J Health Commun. 2010;15(Sup3):147–56. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR Institute of Medicine. Committee on understanding and eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in health care, board on health sciences policy. Washington: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miranda PY, Tarraf W, González HM. Breast cancer screening and ethnicity in the United States: implications for health disparities research. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(2):535–42. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chandra A. Who you are and where you live: race and the geography of healthcare. Med Care. 2009;47(2):135–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a4c5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary RR. Residential segregation and the availability of primary care physicians. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(6):2353–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):575–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zuvekas SH, Olin GL. Validating Household Reports of Health Care Use in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(5 pt 1):1679–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sing M, Banthin JS, Selden TM, Cowan CA, Keehan SP. Reconciling medical expenditure estimates from the MEPS and NHEA, 2002. Health Care Financ Rev. 2006;28(1):25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Selden TM, Sing M. The distribution of public spending for health care in the United States, 2002. Health Aff. 2008;27(5):w349–59. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.w349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.