Abstract

Background

Healthcare professionals throughout the developed world report higher levels of sickness absence, dissatisfaction, distress, and “burnout” at work than staff in other sectors. There is a growing call for the ‘triple aim’ of healthcare delivery (improving patient experience and outcomes and reducing costs; to include a fourth aim: improving healthcare staff experience of healthcare delivery. A systematic review commissioned by the United Kingdom’s (UK) Department of Health reviewed a large number of international healthy workplace interventions and recommended five whole-system changes to improve healthcare staff health and wellbeing: identification and response to local need, engagement of staff at all levels, and the involvement, visible leadership from, and up-skilling of, management and board-level staff.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to identify whole-system healthy workplace interventions in healthcare settings that incorporate (combinations of) these recommendations and determine whether they improve staff health and wellbeing.

Methods

A comprehensive and systematic search of medical, education, exercise science, and social science databases was undertaken. Studies were included if they reported the results of interventions that included all healthcare staff within a healthcare setting (e.g. whole hospital; whole unit, e.g. ward) in collective activities to improve physical or mental health or promote healthy behaviours.

Results

Eleven studies were identified which incorporated at least one of the whole-system recommendations. Interventions that incorporated recommendations to address local need and engage the whole workforce fell in to four broad types: 1) pre-determined (one-size-fits-all) and no choice of activities (two studies); or 2) pre-determined and some choice of activities (one study); 3) A wide choice of a range of activities and some adaptation to local needs (five studies); or, 3) a participatory approach to creating programmes responsive and adaptive to local staff needs that have extensive choice of activities to participate in (three studies). Only five of the interventions included substantial involvement and engagement of leadership and efforts aimed at up-skilling the leadership of staff to support staff health and wellbeing. Incorporation of more of the recommendations did not appear to be related to effectiveness. The heterogeneity of study designs, populations and outcomes excluded a meta-analysis. All studies were deemed by their authors to be at least partly effective. Two studies reported statistically significant improvement in objectively measured physical health (BMI) and eight in subjective mental health. Six studies reported statistically significant positive changes in subjectively assessed health behaviours.

Conclusions

This systematic review identified 11 studies which incorporate at least one of the Boorman recommendations and provides evidence that whole-system healthy workplace interventions can improve health and wellbeing and promote healthier behaviours in healthcare staff.

Introduction

Healthcare professionals throughout the developed world have markedly high rates of sickness absence, burnout, and distress compared to other sectors [1–7]. With the added pressure on healthcare systems, and thus on healthcare staff, of rapidly aging populations and burgeoning chronic disease burdens [8], there is increasing interest in improving both the mental and physical health and wellbeing of healthcare professionals [9, 10]. There is a growing call for the ‘triple aim’ (improving patient experience, patient outcomes, and efficiency) to become the ‘quadruple aim’, with the inclusion of improving healthcare staff experience of care delivery [11, 12]. In the United Kingdom (UK) the National Health Service (NHS) in England’s Five Year Forward View [9] identifies NHS staff health and wellbeing as a priority for the NHS.

Sub-optimal health behaviours of healthcare practitioners in the workplace are linked to stress, illness, increased healthcare costs, obesity, high staff turnover, errors, and poor quality healthcare delivery [4, 13]. However, despite concerted policy and research efforts in the last decade designed to support and improve their health and wellbeing (for example [9, 10]), the acute and long term sickness absence of UK healthcare deliverers remains high [14].

Interventions to improve healthcare staff health and wellbeing have primarily focused on supporting or improving individual coping skills rather than affecting the workplace environment such that it promotes healthier behaviours. Whilst personal coping skills mediate the effects of stressors at work on health and wellbeing, i.e. the ability to deal with environmental stressors at a personal level [5, 7, 15], research points to the potential preventative benefits of targeting the workplace at a system-level (including organisational, cultural, social, physical aspects) in creating sustainable and effective health and wellbeing interventions [16].

The Boorman review [17], commissioned by the UK Department of Health to specifically address the health and wellbeing at work of healthcare staff, highlighted the need for whole-system interventions which incorporate input from staff regarding their local needs and contexts and the involvement of management staff at all levels of the organisation. The review proposed five system-level changes for healthcare workplaces to improve staff health and wellbeing: understanding local staff needs, staff engagement at all levels, strong visible leadership, support for health and wellbeing at senior management and board level, and a focus on management capability and capacity to improve staff health and wellbeing. In the United Kingdom, these healthcare workplace improvement plans are supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and are incorporated into the NHS Health and Well-being Improvement Framework [18].

In this systematic review, we sought to identify healthy workplace interventions in health care settings which used elements of this whole system approach and to determine whether they improve the health and wellbeing and promote healthier behaviours in healthcare staff.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted following the general principles published by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) [19] and is reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [20]. A pre-defined protocol was developed following consultation with topic and methods experts, and is available from the Peninsula Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (PenCLAHRC) website (http://clahrc-peninsula.nihr.ac.uk/est-projects.php). This study has been reviewed and approved by the Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry Research Ethics Committee, now under the auspices of the University of Exeter Medical School Research Ethics Committee.

Literature search and eligibility criteria

The search strategy was constructed using a mixture of controlled vocabulary terms and free text terms after consultation with topic experts and examination of key papers. The master search strategy is shown in S1 Fig. No language or date restrictions were applied. This search was applied to AMED, CINAHL (via NHS Evidence), Embase, Medline, PsycINFO (all via OVID), SportDISCUS (via EBSCO), the Cochrane Library (via Wiley), Science Citation Index expanded and Social Sciences Citation Index (all via the Web of Knowledge interface). All databases were searched from inception. The main search was run in July 2011, and updated in October 2013 and September 2016. The bibliographies of systematic reviews identified during the screening process and of all papers meeting the inclusion criteria were scrutinised for any additional studies cited. The following websites were searched: UK Department of Health http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/index.htm; UK Department of Work and Pensions http://www.dwp.gov.uk/; US Department of Health and Human services http://www.hhs.gov/; Health Canada http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/index-eng.php; Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/Home. In addition, the online contents of the American Journal of Health Promotion and International Journal of Workplace Health Management were hand searched for additional articles. These were selected because they were identified as key journals by an expert stakeholder.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they reported interventions which were targeted at all staff within a healthcare setting (for example a whole hospital, health centre, or unit), were predominantly delivered as group rather than individual activities, and measured the impact on health behaviours or psychological wellbeing in healthcare professionals (outcomes chosen a-priori). Studies in which the intervention was solely aimed at a subgroup of the population (e.g. those with high cholesterol or smokers) were excluded.

Randomised controlled trials (RCT), before and after studies (with or without control), case control, cohort studies and survey designs were included.

Study identification

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to all titles and abstracts by one reviewer (JP, SLB, AB or JTC) and double screened by a second (JP, SLB, AB, KW, LC, or JTC). Duplicates were identified, checked, and excluded. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (LF or KW) where necessary. The full text of potentially relevant articles was retrieved and screened independently by four reviewers (four of: JP, SLB, KW, LC, and JTC); discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (as appropriate, one of: AB, LF or KW).

Data extraction and quality assessment

A data extraction and quality assessment tool was developed and piloted for suitability on four papers by SLB and KW. Data extraction and quality assessment were undertaken by SLB and checked by KW; any disagreement was resolved through discussion.

Assessment of study quality was carried out using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [21] and the EPOC guidance for randomized controlled trials, controlled before and after studies and interrupted time series (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group [22]).

The following data were extracted from each eligible article (S2 Fig): study design; geographic location of study (country); numbers eligible to participate, numbers participating, loss to follow up; summary characteristics of the study population; details of the intervention; whether the intervention was designed to address a local need; whether and which stakeholders were involved in the development and implementation; whether senior management were involved and in what way, including whether there was visible leadership from or upskilling of management staff; treatment of any control group; duration of follow-up; primary and secondary outcomes, outcome measures and intervention effects. Details on whether the intervention was going to be continued at the site after the initial evaluation were also looked for.

Data analysis

As the studies as well as the workplace health and wellbeing interventions reviewed were heterogeneous in their design, implementation and outcomes, an overall meta-analysis was not appropriate, rather we aimed to describe the nature of the interventions, whether they engaged staff, and the outcomes. Study and intervention details were put in to tables, with columns for the whole-system recommendations and rows for description of the study/intervention. This supported us to identify patterns in relation to whether and how the studied intervention aimed to 1) engage staff at all levels of organisation in activities and be responsive to local need and context (relating to whole-system recommendations 1 & 2 [17]) and 2) engage, involve and up-skill leadership staff (whole-system recommendations 3, 4, & 5 [17]).

We provide a narrative review of overall patterns of whether and how we believe the interventions in the included studies take a whole-system approach as described in the Boorman recommendations [17], commenting on whether and how the groups of interventions improved the health and/or wellbeing and/or increased health behaviours of healthcare staff.

Results

Identified studies

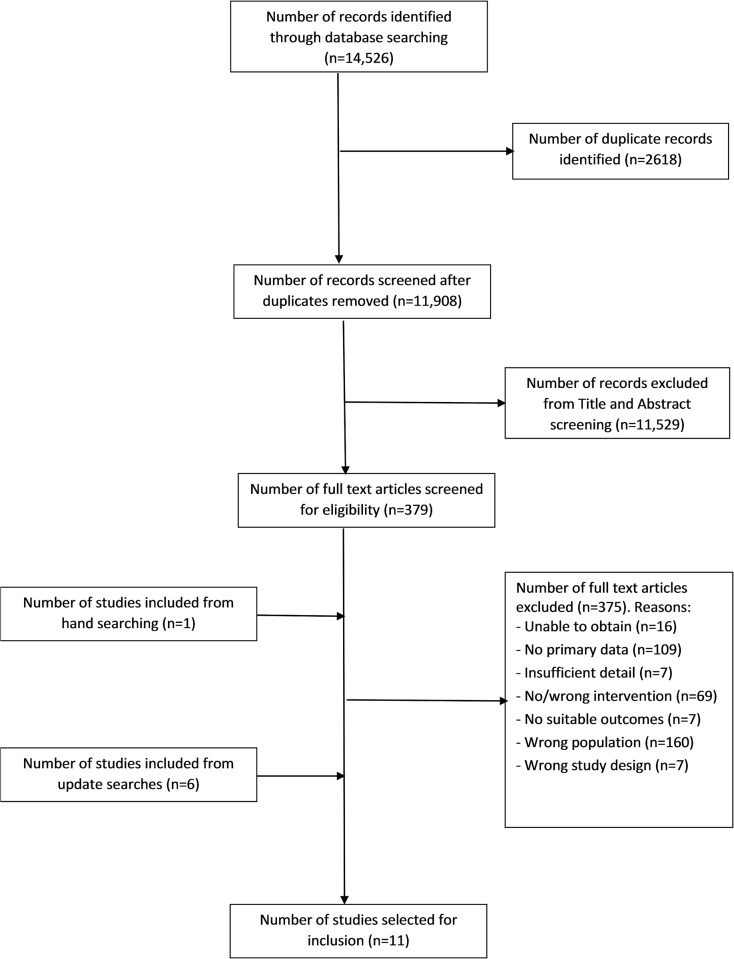

While the original searches retrieved a total of 14,526 records, the review process identified eleven studies to be included (Fig 1). After removing duplicates, 11,908 unique records were downloaded into the reference manager software Endnote to form the master library. The full texts of 379 papers were retrieved for closer examination. Three hundred and seventy five papers were excluded (Fig 1). Update searches (Oct 2013 and Sept 2016) identified a further 7 studies (6 from update searches and 1 from hand searching). A total of eleven studies [6, 23–32] were included, and are summarised in Tables 1–3.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1. Summary of design and quality of studies in the systematic review.

| Randomised Controlled Trials | ||||||||||

| Study | Random allocation | Treatment allocation concealment | Baseline measurement | Reliability of outcome measure/s | Blinding | Adequacy of follow-up (>80%) | Protection against contamination | |||

| Lemon, 2010 [28], USA | Randomised from matched pairs. Method not stated. | None | Completed | Partial | None | Adequate (20% lost to follow-up) | Cluster-randomised | |||

| Sorensen, 1999 [23], USA | Completed. Method not stated. | None | Completed | Insufficient | None | Not reported (baseline and follow-up questionnaires not linked by individual) | Cluster-randomised. | |||

| Sun, 2014 [32] China | Stratified site randomisation | None | Completed | Sufficient | None | Inadequate (50% lost to follow-up) | Cluster-randomised | |||

| Uchiyama, 2013 [29], Japan | Completed. Method not stated. | None | Completed | Sufficient | None | Adequate (20% lost to follow-up) | Cluster-randomised | |||

| Controlled before-after studies | ||||||||||

| Study | Second site control | Treatment allocation concealment | Baseline measurement | Reliability of outcome measure/s | Blinding | Adequacy of follow-up (>80) | Protection against contamination | |||

| McElligot, 2010 [26], USA | Convenience sample: Experimental units previously scheduled to programme. | None. Not possible. | Completed | Sufficient | None | Inadequate (>30% lost to follow-up) | Cluster-randomised | |||

| Before-after studies (no control) | ||||||||||

| Study | Baseline measurement | Matching of samples if not same people | Reliability of outcome measure/s | Adequacy of follow-up (>80) | ||||||

| Blake, 2013 [27], UK | Completed | Non-matched samples | Partial | Inadequate (22% lost to follow-up) | ||||||

| Dobie, 2016 [30], Australia | Completed | n/a | Sufficient | Adequate (none lost to follow-up) | ||||||

| Hess, 2011 [25], Australia | Completed | n/a | Partial | Inadequate (33% lost to follow-up) | ||||||

| Petterson, 1998 [6], Sweden | Completed | n/a | Partial | Inadequate (25% lost to follow-up) | ||||||

| Survey Studies (no control) | ||||||||||

| Study | Baseline measurement | Pre- and post- measures | Reliability of outcome measure/s | Adequacy of follow-up (>80) | ||||||

| Jasperson, 2010 [24], USA | None | No pre-, only 3 months post-events | Low | n/a | ||||||

| Cohort study | ||||||||||

| Study | Baseline measurement | Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Comparability of cohorts | Assessment of outcome | Length of follow-up | |||

| Wieneke, 2016 [31], USA | None | Somewhat representative | Drawn from same community as exposed cohort | Written self-report | Study controls for any additional factor | Self-report (insufficient reliability of outcome measure) | No follow-up | |||

Table 3. Summary of interventions in included studies including whether they address aspects of the five whole-system recommendations and their effectiveness at improving healthcare staff health and wellbeing and/or health behaviour change (yes, partial, no).

| Study | Intervention | Population /Number approached (no. accepted) /Percentage female | Setting | Engagement of staff at all levels of organisation in activities and responsivity to local need and context (relating to whole-system recommendations 1 & 2, Boorman, 2008) | Engagement, involvement and up-skilling of leadership staff (whole-system recommendations 3, 4, & 5, Boorman, 2008) | Improved the health and/or wellbeing and/or increased health behaviours of healthcare staff (yes O; partial I; no—) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed in response to identified local need | Engagement of all staff in workplace system in group activities to improve health and wellbeing | Choice of intervention activities to participate in | Local staff involved in intervention development / implementation | Adaptive and responsive: ground-up tailoring of activities to local need and context throughout | Strong visible leadership | Support for health and wellbeing at senior management and board level | A focus on management capability and capacity to improve staff health and wellbeing | |||||

| Dobie, 2016 [30], Australia | Brief mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) programme. It consisted of 15-minutes of group daily guided experiential practice, including five minutes of simple body movements adapted from Thich Nhat Hanh, and 10 minutes of breathing awareness and reflection exercises using scripts adapted from Kabat-Zin, Linehan, Williams, Teasdale, and Thich Nhat Hanh. Sessions ran at the commencement of the morning shift each work day and concluded with an opportunity to debrief. The programme also included three 30-minute education sessions during weeks 2, 4 and 6 designed to increase participants’ understanding of the core components of mindfulness and explore any challenges participants experienced during their practice. MBSR practice focuses on individual coping but the team delivery design of the intervention also enabled whole-system change: Every morning at the beginning of the first shift, the nine staff sat down together for 15 minutes of guided mindfulness practice and five minutes debrief, and there were thirty-minute group education sessions in weeks 2, 4, and 6 to increase participants’ understanding of the core components of mindfulness and explore any challenges participants experienced during their mindfulness practice. | All staff in unit / not stated (9) / f = not stated | Public hospital mental health unit | O | O | |||||||

| Hess, 2011 [25], USA | Workplace nutrition and physical activity promotion. The intervention ran for a total of 12 weeks. A self-selected group participated in the intervention as only 400 places were offered to the 2900 strong workforce; of those 66% completed the intervention. All participants were provided with a registration pack that included: information leaflet about how the challenge works; pedometer; healthy eating log book; water bottle; sandwich box; ‘Healthy Food Fast’ cookbook; and Measure Up campaign resources. Participants were required to wear a pedometer and record their daily steps for 12 weeks on the 10,000 steps website. Participants were also required to record their daily consumption of fruit, vegetable, water and healthy breakfast in the healthy eating log book during a four-week period, from week five to week eight (for feasibility purposes). Participants’ steps and dietary information were added to produce a team score, which was displayed weekly in the staff canteen. Weekly walks were led by Health Promotion staff during the challenge and were available for all staff at Liverpool Hospital. Other motivational and environmental strategies implemented during the intervention included: posters identifying local walking routes and healthy messages; weekly motivational e-mails; ‘footprints’ directing people to use the stairs; and healthy messages on pay slips. After completion of the challenge, prizes were awarded to the teams who took the most steps and ate the healthiest. | All hospital staff / 2900 (399) / f = 92.8% | Hospital site | O | O | |||||||

| McElligot, 2010 [26], USA | Promotion of culture of caring and safety. Collaborative Care Model (CCM) program created to promote a culture of caring, focusing on relationships and patient-centred care, fostering and sustaining a healing environment and a culture of safety. The program components were adapted from the Holistic Nursing Handbook and best practice models (Dossey & Keegan, 2009). The didactic content included interactive lectures on the CCM program, American Holistic Nurses Association values, formation of the collaborative care council, and a code of professionalism. The experiential content included completion of the Health Promoting Lifestyles Promotion II tool, option for study participation, and experiences with imagery, appreciative inquiry, and a sharing circle. Aim of the intervention was for participants to be able to: Define the CCM as the professional practice model of the institution; Relate the CCM to the five core values of the AHNA; Participate in the self-assessment of personal health-promotion behaviours through tools and discussion; Demonstrate the use of appreciative inquiry as a method of change; Identify one self-care health-promotion goal and one group health-promotion goal. Activities included: interactive lectures; HPLP II tool completion; self-assessment of personal health-promotion behaviours; discussion; healthy behaviour goal-setting; experience of imagery; appreciative enquiry method for change, sharing circle. | 103 registered nurses / 408 (270) / f = 95% | Hospital units | O | O | O | O | |||||

| Blake, 2013 [27], UK | NHS workplace wellness intervention (including: dedicated website; timetable of exercise sessions; staff gym; cycle storage and showers; slimming classes; healthy eating schemes; health campaigns such as wellbeing week, active commuting, and mental health week). Workplace champions were employed to promote the services and facilities. Champions were identified as employees who recognised importance of health and wellbeing and were paid to do this work during their core hours. | All hospital staff / 7065 (1452) / f = 80% | Large NHS organisation | O | O | O | O | |||||

| Sorensen, 1999 [23], USA | Treatwell 5-a-Day for Better Health campaign incorporating three key theoretical constructs: 1) employee involvement, 2) socio-ecological approach targeting intrapersonal, interpersonal, and organisational influences on eating behaviour, 3) the use of adult learning and behaviour change strategies. Intervention included: newsletters; posters; nutrition education hour and 10 session discussion series; multiple themed activities; organisational environment changes, for example point-of-purchase labelling and vending machine signage; and family activities, for example family festivals, health fairs, picnics, and Fit in Five learn-at-home nutrition education programme. The study compared a minimal intervention group (i.e. no activities, public awareness campaign, and one hour of nutrition education), a worksite-only group (i.e. all elements of intervention plus worksite activities), and a worksite-plus-family group (i.e. all elements of intervention plus worksite-plus-family activities, family festivals, and Fit-in-Five at-home education program. | 1306 community health centre staff / 1588 (1359) / f = 84% | 22 community health centres | O | O | O | I | |||||

| Jasperson, 2010 [24], Sweden | Wellness program developed by two departments at hospital and delivered by a part-time coordinator and 17 champions from departments from a variety of job roles who met monthly. Main activities were three annual team walking competitions in which pedometer steps per day were added up for each team and the progress of each team in miles across a map was presented in a shared area of the hospital. Walking competitions happened yearly and lasted 2 months. Other activities included lectures. | 1700 hospital staff / 1700 (year 1 = 610, year 2 = 812) / f = not reported | 2 hospital departments | O | O | O | O | I | ||||

| Sun, 2014 [32], China | Workplace Social Capital intervention including four activities: Team leadership training activity (one activity): A one-day team building courses for directors (team management and communication skills and practical team leadership experiences). The directors in intervention centers were asked to join and coordinate all non-leadership activities. Non-leadership activities for staff (three activities): Self-organizing voluntarily public services for disadvantaged community residents (each intervention center was asked to self-organize public services for the older adults, the disabled or the poor within their communities); Half-day group psychological consultation (half-day consultations for each center focusing on team communications and stress management); One-day outdoor experiential trainings aiming at improving team coordination and communications. | 480 staff / (447) / f = not stated | 20 community health centres | O | O | O | O | O | O | — | ||

| Lemon, 2010 [28], USA | One of seven projects in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Overweight and Obesity Control at Worksites initiative. Employee and leadership advisory committees helped develop site-tailored strategies to promote organisational and social norms related to eating and physical activity in the workplace to improve health behaviours and BMI. The Step Ahead ecological intervention approach targets change at the organization, interpersonal work environment, and individual levels. The intervention was developed using participatory research. Engaged leadership support and assistance during intervention development stage and involved them in development of the intervention. “Top down” approach of first engaging the support of top leadership. Strong leadership support was made clear to cafeteria and facilities middle management and staff members, whose cooperation was needed to implement changes. Employee involvement in intervention planning and development in focus groups. Overall the groups were enthusiastic about the project. Involved in suggesting and discussing potential activities prior to implementation. All staff invited to participate in focus groups at each hospital. Activities/interventions included: organisational leadership, climate, culture, and capacity to promote an environment supportive of weight control; social marketing; walking groups; signs on stairs; walks with the president; nutritional information in café; seasonal farmers market; individual and group challenges. | 1983 hospital staff / 1983 (899 accepted, 806 took part) / f = 81% | 6 hospitals from one healthcare system | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | I | |

| Petterson, 1998 [6], Sweden | Inclusive, staff-led intervention ‘process’, departments used own autonomy to choose intervention elements, group goal setting, communication, cooperation, and social relations within each department. The intervention program was initiated by the hospital management with a large questionnaire study of work environment and health of all hospital staff. Each department management and staff were encouraged to engage in the improvement of their own work environment. Survey feedback was a means to get all staff involved in the process by initiating discussions on local work problems, needs for improvements and to stimulate activities to change negative work conditions. Based on survey feedback of results presented as histograms, of its own department values comparable to other departments and hospital mean values, each department had to choose those improvement areas most relevant to its organization, to make goals for workplace improvements and to plan for activities to realize those goals. All staff were encouraged to contribute to the formulation of goals as well as to take part in decided activities. A lot of activities were initiated but there was a great variation across departments with regard to time spent and to choice of activities. Each department had the possibility to apply for financial support for special activities. Next to more common activities such as group discussions on new competence needs, supervision, leadership qualities, information channels, work or meeting routines, flexible working hours, and on organizational goals and visions, separate department programs included study visits to other hospitals, quality circles or cources, debriefing or physical training. Lecturers were invited to talk about issues like work and stress and consultants were engaged to investigate the needs of new competence of the local organization. Most of the departments also arranged social activities. Department programs were primarily expected to facilitate communication and cooperation, to increase staff participation, and also to improve work efficiency and social relations which in turn was supposed to improve perceived work quality, supporting resources, and staff health and well-being. | 2617 hospital staff / 4613 (3506) / f = not stated | Hospital departments | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | I | |

| Uchiyama, 2013 [29], Japan | Participatory intervention for psychosocial work environment: all employees were invited to share good practice and barriers to working, including planning of problems, needs, progress and creating a plan of activities. The intervention was unit based, focused on active employee participation, and based on action planning to improve the work environment. All members in the intervention units were expected to participate in a series of activities designed to improve the work environment. Development: Results of a pre-intervention survey were reported to each unit and used for target identification and prioritization of the targeted psychosocial work environment, and as an index of improvement. In reference to their own unit’s results, all members of the unit were asked to describe their ideal work environment and invited to develop action plans to improve their psychosocial work environment. Comprehensive information on mental health in the workplace and psychosocial work environment as a source of stress was provided to each unit. Champions: Sub-chief nurses in each intervention unit were appointed as champions to facilitate activities within their own units. 30-minute group meetings of champions to share information on good practices and obstacles. 30-minute individual interviews with each champion conducted by the first author to provide advice on facilitating other staff activities in their units. Champions then shared necessary information with staff of their own units. Champions filled out task sheets after every 30-minute group meeting to clarify the problems, needs, and progress of their unit and to help plan execution of the activities. Champions were assigned to list the issues of their own units that needed to be improved and incorporate the opinions of unit members. They identified existing problems, while considering the effectiveness, feasibility, priority, and time cost of improvements. Implementation: Nurses in the intervention group started to improve their psychosocial work environment based on the action plans proposed in the development phase. Suggestions for further improvement and sustaining autonomous activities were discussed during this period. | 496 nurses in units / 434 (401) / f = 100% | Hospital units | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | I | |

| Wieneke, 2016 [31], USA | The wellness champion program was designed to improve the health and wellbeing of employees by extending the reach of the onsite healthy living programs and staff into the worksite to create a supportive work environment for having a healthy lifestyle. A multistep process was utilized to implement a cost-effective wellness champion program across the organization. Workplace wellness champions created workplace wellbeing activities from a range across several domains for their local work area. These activities were intended to impact the culture of health through organisational and peer support for employees. Workplace wellness champions are provided ready-made program resources and given the autonomy to promote programs of personal and work group interest for their local work group, including physical activity, volunteerism, teambuilding, social interaction, stress management, and new experiences such as healthy potlucks, walking or stair-climbing campaigns, and team weight-loss competitions. Wellness champions promote health and wellness opportunities via print, electronic, and in-person communications. The first two worksite wellness champions designed the intervention, resources and the training of the more than 440 now existing workplace wellness champions. | 4129 staff with workplace wellness champion in their local work area; (2315) of which 1630 were familiar with the workplace wellness program / f = not stated | One large academic medical centre | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

Study characteristics and quality

Outcomes

All reviewed studies included self-reported measures of individual health behaviours and health outcomes, and four studies [6, 23, 28, 29] included self-reported measures of the psychosocial workplace environment (see Table 3). Two studies [28, 32] reported Body Mass Index (BMI).

Study design and quality

The overall quality of included studies was considered to be poor (Table 1). The main reasons relate to the outcome measures, which were generally low in reliability, variable in validity, and heterogeneous; lack of controls; variable follow-up length; and high attrition rates.

Reliability and validity of outcome measures: Six [6, 23–25, 27, 28, 31] out of the eleven studies had partial or low reliability of outcome measures. Three studies [6, 23, 24] did not use validated outcome measures. Petterson and colleagues [6] used self-report scales based on the findings of a factor analysis. They report that in general these scales have high internal consistency, though two (job demands and work pressure) had lower internal consistency, leading them to question the ability of these scales to measure unitary dimensions. Some studies used self-report measures. Sorenson and colleagues [23] used self-report survey and process tracking measures (including self-reported number of activities taken part in). Jasperson and colleagues [24] constructed and used a health questionnaire that measured self-reported physical activity and diet and a survey measuring self-reported walking event attendance.

Heterogeneity of outcome measures: Three studies [25, 27, 28] used an objective outcome measure of health (BMI). The other nine studies used subjective self-report measures, and no two of them used the same subjective self-report measures.

Study design: In addition (see Table 1) five of the eleven studies lacked a control group [6, 24, 25, 27, 30], two had no follow-up [24, 31], and one did not report follow-up information because baseline and follow-up questionnaires were not linked by person [23]. Follow up periods varied considerably; in six studies [23–26, 29–31] follow-up (or single time-point) data were collected immediately post intervention. In the remaining studies follow-up data were collected at between 3 months [26, 32] and 5 years [27] after the start of the programme. Follow-up rates also varied as the workforce itself changed over the follow-up period.

Attrition rates: Five of the eight studies reporting follow-up had attrition rates higher than 20% (ranging from just over 20% to 50%) [6, 25–27, 32]. One study reported no attrition; two studies reported 20% attrition (Lemon, Uchiyama); four studies [6, 25–27] reported attrition rates varying from 22 to 33%; one study reported 50% attrition, one [23] did not report attrition rates; and two did not have baseline measurements [24, 31].

Participation: Nine studies [6, 23, 24, 26–32] offered the intervention to all hospital/unit/health centre staff; one study [25] offered the intervention to everyone, but operated on a first come first served basis as there were only 400 places available to the 2900 staff; one study [31] offered the intervention to all staff working in a work area that had a workplace wellness champion working in it. Given the nature of the included interventions (i.e. aiming to affect whole-system change), it is hard to estimate overall participation rates other than in the specific activities which were delivered within the intervention programme.

None of the studies described the interventions in sufficient detail to allow replication. One study [30] offered the manual for their brief MBSR intervention upon request.

Effectiveness of interventions

Included studies

All interventions were deemed by their authors to be at least partly effective (Table 2). Two studies reported statistically significant improvement in objectively measured physical health (BMI; [27, 28]) and eight in subjective mental health [6, 24–31]. Six studies reported statistically significant positive changes in subjectively assessed health behaviours [23–28].

Table 2. Design, outcomes measures, analysis and results of the eleven included studies.

| Study | Study design | Outcome Measure/s | Duration of follow-up from baseline (weeks) | Analysis | Results | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistically significant change in physical health | Statistically significant change in mental health and wellbeing | Statistically significant change in health behaviour | ||||||

| Blake, 2013 [27], UK | Before-after study (no control) |

|

260 | Non-matched samples were comparable at baseline and follow-up. Cramer’s V, ANOVA, partial eta squared. |

|

O | O | O |

| Dobie, 2016 [30], Australia | Before-after study (no control) |

|

8 |

|

|

O | ||

| Hess, 2011 [25], Australia | Before-after study (no control) |

|

12 |

|

|

O | O | |

| Jasperson, 2010 [24], USA | Survey study (no control) |

|

12 | None |

|

O | O | |

| Lemon, 2010 [28], USA | Randomised-Controlled Trial |

|

102 | Multivariable linear regression models for survey data to assess associations of demographic and job characteristics with the 3 worksite perceptions scales and relationships of the 3 worksite perceptions scales with BMI, fruit and vegetable consumption, saturated fat consumption, and physical activity, controlling for demographic and job characteristics. |

|

O | O | |

| McElligot, 2010 [26], USA | Controlled before-after study |

|

12 (+2 month response window) | Multivariate ANOVA: pre-post and treatment-versus-control analyses. |

|

O | O | |

| Petterson, 1998 [6], Sweden | Before-after study (no control) |

|

52 | ANOVA pre- versus post- and high- versus low- activity uptake departments. Based on activity ratings, departments were separated into two groups, one highly active (n = 20) and one less active (n = 17) in the change process. The groups were compared regarding measures of work quality, supporting resources, and health. |

|

O | ||

| Sorensen, 1999 [23], USA | Randomised-Controlled Trial |

|

104 | Pearson product moment correlations calculated to evaluate bivariate relationships between process tracking variable and outcome variables. |

|

O | ||

| Sun, 2014 [32], China | Randomised-Controlled Trial |

|

26 | Bivariate difference-in-differences (DID) analysis using paired T-test to analyze the facility-level WSC intervention effects. The DID method compares the differences in WSC in pre- and post-intervention periods in the intervention and control groups. |

|

|||

| Uchiyama, 2013 [29], Japan | Randomised-Controlled Trial |

|

26 | Paired t-tests to assess changes in score for each variable in each group. ANCOVA for each variable at post-intervention, controlling for pre-intervention score. Qualitative content analysis for process evaluation |

|

O | ||

| Wieneke, 2016 [31], USA | Cohort study |

|

n/a | The survey items were categorical. Responses to levels of agreement to particular statements (5-point Likert agreement scale) were summarized with percentages. Overall health and wellness (scale from 0 [worst]– 10 [best]) was summarized with percentages (respondents reporting level of 8+) as well as means and standard deviations (SD). Level of agreement and overall health and wellness were compared between program participants versus those not familiar with the program using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. The survey items specific to the wellness champions program were summarized with percentages among those who reported being aware of the program. |

|

O | ||

Due to the heterogeneity of types of study and measures used, it is difficult to make meaningful comparisons between the studies. We describe the interventions in relation to the degree to which they included the whole-system recommendations for healthy workplace interventions in healthcare settings [17].

Included interventions

Interventions varied in terms of whether and how they incorporated the five whole-system recommendations [17] (Table 3) and their overall effectiveness (as reported by the authors of each study) in improving healthcare staff health and wellbeing and/or health behaviour change (Table 3: yes = O; partial = I; no = —).

Recommendations 1&2: Identifying and responding to local need and engaging staff at all levels

The eleven studies varied considerably in how they tailored their interventions to local need and engaged staff at all levels (Table 3; [17]). Interventions were: 1) pre-determined and fixed from the outset without choice of activity [25, 30]; 2) pre-determined with choice of activity [26]; 3) had choice of a wide range of activities and some adaptivity of the programme, with further activities added in response to take-up [23, 24, 27, 32]; and, 4) adaptive and responsive workplace programmes, taking a participatory approach from the beginning and creating programmes responsive and adaptive to staff needs, in which the implementation process was part of the intervention [6, 28, 29, 31].

1) Pre-determined interventions with no choice of activities

Two studies offered a fixed set of activities, including some element of group activities, to all staff in one workplace. These activities were not created in response to local need, and nor was there choice about which activities to participate in [25, 30].

An eight-week Mentalisation-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) intervention for staff in a 12 bed mental health inpatient unit (MBSR practice focuses on individual coping but the team delivery design of the intervention also enabled whole-system change; Table 3) resulted in a significant decrease in self-reported psychological distress, including reduced levels of self-reported anxiety [30]. There was no overall increase in the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills, suggesting that these changes in distress and anxiety may have resulted from the increased communication and activity-sharing between the work unit [30].

Implementing a pre-determined 12 week intervention to improve physical activity and nutrition behaviours across a hospital site using a team-based approach and peer support (Table 3) resulted in those completing the intervention reporting significantly higher physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, water intake, and feeling less stressed than the non-completers [25].

2) Pre-determined interventions with some choice of activities

One study [26] had a fixed set of activities and some choice about which activities to participate in. In response to an identified need, a self-care plan and holistic learning programme on one hundred and three nurses’ health-promoting behaviours in intervention units over twelve months resulted in a significant difference pre- and post- intervention in nurses in intervention versus control units in overall Health Promoting Lifestyles Promotion (HPLP) II scores, and the sub-scales of stress management, nutrition, and spiritual growth [26].

3) Choice and some adaptivity of the programme (supplementary activities)

Five interventions [23, 24, 27, 28, 32] offered an initial range of activities for the workforce to participate in, as well as providing supplementary activities during the implementation of the interventions.

Three of the five interventions involved “Workplace Champions” whose roles were delivery as well as gathering feedback and planning further activities [23, 24, 27]. In one intervention [23], the role of the workplace champion was to further refine and adapt the intervention activities delivered depending on identified need and context. Employee leadership and advisory boards were also created to develop site-specific strategies and approaches.

Three interventions [23, 28, 32] had an explicitly participatory approach both in the design and the delivery. Two [23, 28] included External Advisory Boards at each intervention site to engage the workforce and tailor activities to their needs and two had a strong emphasis on engagement of leadership and staff in the development and tailoring of intervention activities [28, 32]. The latter two contained activities designed to engage the whole worksite and develop relationships to support healthy behaviours, e.g. a directors’ team-building course, and activities for all staff (including leadership) to improve team coordination, communication and stress management [32].

Uptake of the intervention was not determined for any of the studies, probably as all offered a variety of activities as well as making some environmental changes; one study [24] reported that a third of all the employees participated in a competition organised as part of the intervention.

Four of the five studies [23, 24, 26, 27] reported an improvement in health and wellbeing behaviours (Table 3); increase in fruit and vegetable consumption (three-arm randomised controlled trial [23]); increased physical activity (before and after study with no control [27]; self-report, survey design, no control [24]); increase in healthy eating post-intervention [26]; and improved self-reported nutrition post-intervention in a controlled before and after study [26]. Two studies found no change in BMI [27, 28].

Three studies found improvements in employee mental health: improved job satisfaction (but no effect on mood or work perceived work performance [27]); more self-reports of staff satisfaction in post-intervention survey [24]; improvements in stress management and spiritual wellbeing post-intervention compared to controls [26].

One study [28] observed improved employee perception of worksite commitment to their health and wellbeing and that changes in perceptions of co-worker norms changed outcomes for participants: higher perception of co-worker normative healthy eating behaviours was associated with greater fruit and vegetable consumption and less fat consumption; and higher perception of co-worker normative physical-activity behaviours was associated with greater total physical activity. Perceived co-worker support also increased in the intervention arm in another study [23].

One study [28] observed a significant participation dose-response effect: When intervention exposure was used as the independent variable BMI decreased for each unit increase in intervention participation at 24 months (Table 3).

4) Adaptive and responsive workplace programmes

Three large hospital studies [6, 29, 31] viewed the process of developing the intervention to be a part of creating a healthy workplace: a before and after study involving over three thousand employees from thirty seven regional hospital departments in Sweden [6]; a cluster-RCT in twenty four hospital departments in two hospitals in Japan [29]; and a cohort study comparing people exposed and not exposed to a workplace wellness champion intervention (self-reported) within a large academic medical centre [31]. The three interventions were adaptive and responsive to local needs and context from development and implementation, right through until the end of the study and beyond. This responsivity provides the opportunity for sustainability after the end of the study, and for processes involved in the intervention to become part of the workplace culture.

All three: aimed to improve the psychosocial work environment by utilising a participatory approach, asking each department or work area to identify the enablers and barriers to workplace wellbeing, and to set goals and identify areas for improvement; appointed key people or “champions” to support the interventions and to act as communicators within and across departments; and used feedback to develop activities responsive to local need (two [6, 29] fed back survey results to local staff and one [31] had workplace wellness champions (Table 3)design activities based on local feedback)

Two studies showed some evidence of a dose-response effect in which greater participation produced greater benefits. When a notice of staff cut-back was announced between baseline and follow-up staff in departments rated as highly active in improvement activities did not deteriorate during the follow-up period in work pressure, organizational climate and coping whereas staff in departments rated as less active did deteriorate [6]. Similarly, participants in a local work area who did versus did not participate in activities rated their overall health and wellness as significantly higher and significantly more of participating versus not participating in a local area agreed that their co-workers support one another in practicing a healthy lifestyle [31].

One [29] found varying levels of participation across the departments, with staff citing “realising that change was possible” and responding to identified needs as positive ways of improving the psychosocial work environment; concomitantly, the lack of time and common understanding, staff changes, and a feeling that activities were not responding to staff needs were given as reasons why the environment did not change. They observed no overall effect on mental health status, but significant increases in participatory management, co-worker support, and job control versus control.

Recommendations 3, 4, & 5: Engagement, involvement and upskilling of management and board-level staff

Three of the five recommendations involve the engagement and support of management and board-level staff in intervention activities, including strong visible leadership, support for the health and wellbeing of staff, and the targeting of resources on improving management capability and capacity to deliver this increased visible leadership and support. Despite this emphasis in the recommendations these activities were notably lacking in seven interventions reviewed. Promisingly, five focused considerable resource on engagement, involvement and upskilling of management staff [6, 28, 29, 31, 32]. Two significantly improving mental health and wellbeing of healthcare staff [29, 31], one reducing deterioration in mental health measures for people with high versus low participation rates [6], one significantly improving physical health (BMI) and health behaviours [28]. The fifth found no significant effect on mental health and wellbeing [32].

Four interventions involved extensive management involvement as champions [28, 29, 31, 32]. Sun and colleagues [32] Engaging higher management staff in local staff activities and creating opportunities for increased communication, group solidarity and group coordination, alongside intervention activities to improve leadership and management and communication skills of higher levels of management (e.g. directors of intervention centres were engaged and educated about the importance of activities in groups for staff, and then were involved in implementing and taking part in the group activities, having the responsibility to plan, coordinate, and monitor the group’s activities and to convey a vision, inspiring team collaboration) resulted in no significant impact of their intervention on workplace social capital, the measures of which included items on vertical and horizontal trust and communication. In another intervention [31], following efforts to involve management, supervisors and HR in supporting the workplace wellness champions to deliver and implement their locally adapted intervention, twenty-three percent of people engaging with the intervention reported an improved work atmosphere, and significantly more of those participating strongly agreed or agreed that the organisation provides a supportive environment to live a healthy lifestyle compared to those not familiar with the wellness champions. Enthusiastic“buy in” at the upper level of administration and visible strong leadership support, when it improves cooperation by other staff to implement changes [28], produced a significant association between perception of stronger organisational commitment to employee health and a reduction in BMI. When local leadership staff were directly supported to develop their capability and capacity to improve staff health and wellbeing (Table 3) [29], the intervention group showed a statistically significant increase in the psychosocial work environment questionnaire sub-scale of ‘participatory management’, along with self-reports of improved work environment in the process evaluation; however, there was no significant difference in the intervention groups’ scores on the depression scale pre- to post- intervention.

When there was a focus on management visibility and involvement in the feeding back of local results and the active implementation of changes related to locally raised needs, and improving vertical communication between managers and staff, staff in departments that actively participated showed significantly less deterioration in perceived organisational climate compared with staff in departments with low participation [6].

Discussion

This systematic review identified eleven studies of workplace health promotion interventions which sought to enhance the health and wellbeing of healthcare staff by using a whole-system approach to interventions. The low number of identified studies highlights that the impact of whole-system healthy workplace interventions for healthcare workers, as recommended by Boorman [17] is under-researched, and we feel this gap is important for future research to address.

Although the studies were of mixed (mid to low) quality and the intervention designs varied considerably, the reported results suggest that interventions taking a whole-system approach can improve physical and mental staff health and wellbeing and promote healthier behaviours.

Interventions that incorporate at least one of the five whole-system recommendations for improving healthcare worker health and wellbeing [12] resulted in improvements in physical and/or mental health and promoted healthier behaviours in healthcare staff. However, one study [32] incorporated all five of the recommendations in their workplace social capital intervention and did not find any significant change in measures of mental health (workplace social capital measure, see Table 2). It is not possible to draw conclusions regarding the specificity of the interventions as they varied widely in terms of their context, development, design, and implementation, but it is interesting to note that there seems to be no relation between the greater number of recommendations incorporated in interventions and the effectiveness of the study. However, heterogeneity in outcome measures makes this a tentative comparison.

Four studies of interventions offering choice of a range of activities to participate in [6, 23, 28, 31] individually offer some evidence that the greater the level of participation, the greater the individual benefit: greater participation improved: resilience to organisational change [6]; self-rated overall health and wellness [31]; BMI [28]; and fruit and vegetable consumption [23]. The latter study also found enhanced effect of a worksite intervention when there was family participation suggesting that widening activities beyond the workplace to include family and friends may further enhance engagement and improvements to wellbeing.

The suggestion of potential individual “dose-response effect” in these four studies (i.e. more benefit derived from more participation [6, 23, 28, 31] has several implications: firstly, it suggests that attention needs to be given to creating intervention activities that healthcare staff want to engage in and offering a selection of a range of activities, some team- and some individual-based, for participants to choose between. Interestingly, some workplace interventions [28] had the least take-up of team-based activities, whereas others [24] found this the most participative aspect of the intervention.

The four studies that reported findings from their process evaluations [23, 25, 28, 29] all suggested that time was one of the greatest barriers to employee participation in workplace health and wellbeing interventions. Understanding the barriers to participation (such as time, resources, and poor communication about activities) should be part of the process of evaluating any workplace intervention, and having an intervention able to adapt to allow different times and ways of participating should be beneficial.

Although it is hard to make any meaningful comparisons regarding effectiveness, the studies which assessed intervention activity participation [23, 25] suggest that the interventions in which staff were involved from the beginning in determining the activities had greater participation. There was lower participation in interventions with more pre-determined activities, even when there was an opt-in process for staff and hence potentially had a more motivated workforce participating. One study [25] invited 400 of 2900 staff to participate in a 12 week intervention and had 61% participation, compared with the 81% participation in the workplace intervention implemented by another study [23] where employees were involved in the development and implementation of their workplace intervention.

Implications for policy/practice

The Boorman Review [17] called for healthcare workplaces that: support local staff needs; have staff engagement at all levels; have strong visible leadership and support at senior management and board level on health and wellbeing; have a focus on management capability and capacity to improve staff health and wellbeing. Our systematic review shows that interventions incorporating these whole-system approaches can improve healthcare staff health and wellbeing and increase health behaviours.

Only five of the eleven studies focussed on management capability and capacity. There was some evidence from subjective author reports that this focus resulted in enthusiastic engagement from leadership [28, 29, 32]. Of these five interventions, four involved management-level staff as healthy workplace champions. It is interesting to note that the findings of these four studies all involved perceptions of improved workplace culture or atmosphere in participants: improved work atmosphere and environment, more supportive environment to live a healthy lifestyle, more ‘participatory management’, less deterioration in perceived organisational climate, and stronger organisational commitment to employee health (the latter of which was significantly associated with reductions in objectively measured BMI). However, the fifth study found no significant impact of their intervention on measures of vertical trust and communication. These findings provide some evidence that interventions including efforts to engage and involve management staff, such as in the feedback of local results of health and wellbeing surveys and involvement in discussions with local staff of how they would like to address the, in being workplace champions themselves, to make their leadership on health and wellbeing more visible, and to provide training on skills to support the health and wellbeing of their staff, can impact the perception by those staff that management are on their side and that they work in a place with a positive workplace environment.

The finding of potential “dose-response” effects in the four studies that report participation rates suggest that participation and engagement are important in designing and implementing healthy workplace interventions: A flexible intervention with continuous employee involvement and an ongoing evaluation to highlight facilitators and barriers to participation has greater potential to positively affect and sustain health and wellbeing for the healthcare workforce and thus to improve staff health and wellbeing.

Strengths and limitations

The review was conducted according to the principles published by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) and is reported according to PRISMA guidelines (S3 Fig). The review was comprehensive, searching across electronic and grey literature sources to identify studies. There were no language or date restrictions in the searches.

Due to the nature of the topic under consideration, the inclusion criteria in this review were open to a degree of subjective interpretation. For this reason we took all reasonable steps to ensure that eligibility criteria were applied consistently across all identified articles by 1) piloting the criteria on a subset of papers, 2) having two reviewers independently assess the eligibility of all articles with discussion of all disagreements, and 3) involvement of a third reviewer to resolve disagreements where necessary.

Comparison across the approaches utilised to improve health and wellbeing of healthcare professionals was challenging due to the lack of detail provided regarding the specific nature of the components and the mechanisms making up the interventions.

Variable methodological quality, mostly related to the outcome measures used, which were in general low in reliability, variable in validity, and heterogeneous, along with the nature of the study designs prevented any conclusions related to the effect on health and wellbeing outcomes of incorporating more versus less of the five whole-system recommendations being made. Nor were we able to compare the effectiveness of different patterns of whole-system recommendation implementation.

Recommendations for future research

Despite extensive and systematic searching of the literature, we were only able to identify eleven studies that met our inclusion criteria. The low number of identified studies highlights that there is currently limited evidence regarding the effectiveness of whole-system approaches to enable staff health and wellbeing for healthcare professionals in healthcare settings, as recommended by Boorman [17]. Ten out of eleven included studies provide evidence that whole-system approaches to healthcare workplace health interventions that include at least one of the five whole-system recommendations [17] improve physical and/or mental health and promote positive health behaviours in healthcare staff, suggesting this is an area of potentially fruitful inquiry.

The methodological quality of the studies was mostly low, with only five out of eleven studies included being rated as “medium” quality. This systematic review clearly identifies a need for good quality primary research using similar and validated outcome measures to evaluate whole-system approaches to health and wellbeing interventions in healthcare worker populations. Comparative studies of the effectiveness of individual-focused versus whole-system-focused approaches would clarify their relative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Long-term follow-up is necessary to evaluate the sustainability of observed change. More systematic reporting would allow more definitive conclusions about how the conditions for sustainable healthy workplaces for healthcare workers can be created.

The low number of studies and heterogeneous intervention designs and outcome measures used in those studies, makes it challenging to pin down whether and in what way whole-system approaches improve healthcare worker health and wellbeing. Realist reviews of the literature, in which context-mechanism-outcome configurations rather than whole interventions are the unit of analysis, would be of use in establishing what it is about whole-system interventions that works to improve health and wellbeing for healthcare workers, who for, under what circumstances, and in what way.

Conclusion

This systematic review identified 11 studies which incorporate at least one of the Boorman recommendations and provides evidence that whole-system healthy workplace interventions can improve health and wellbeing and promote healthier behaviours in healthcare staff.

Supporting information

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

Funding provided in part to the European Centre for Environment and Human Health (part of the University of Exeter Medical School) by the European Regional Development Fund Programme 2007 to 2013 and European Social Fund Convergence Programme for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly; and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula at the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Data Availability

Data are all from published research articles that are available by using the references in the manuscript.

Funding Statement

Funding provided in part to the European Centre for Environment and Human Health (part of the University of Exeter Medical School) by the European Regional Development Fund Programme 2007 to 2013 (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/erdf-programmes-and-resources) and European Social Fund Convergence Programme for Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (http://www.erdfconvergence.org.uk/esf). This research was also funded in part by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula (http://clahrc-peninsula.nihr.ac.uk/) at the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust (http://www.rdehospital.nhs.uk/). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Lee DJ, Fleming LE, LeBlanc WG, Arheart KL, Ferraro KF, Pitt-Catsouphes M, et al. Health Status and Risk Indicator Trends of the Aging US Healthcare Workforce. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2012;54(4):497 doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318247a379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards D, Burnard P. A systematic review of stress and stress management interventions for mental health nurses. Journal of advanced nursing. 2003;42(2):169–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raiger J. Applying a cultural lens to the concept of burnout. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2005;16(1):71–6. doi: 10.1177/1043659604270980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AbuAlRub RF. Job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses. Journal of nursing scholarship. 2004;36(1):73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper CL, Dewe PJ, O’Driscoll MP. Organizational stress: A review and critique of theory, research, and applications: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petterson I-L, Arnetz BB. Psychosocial stressors and well-being in health care workers. The impact of an intervention program. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;47(11):1763–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruotsalainen J, Serra C, Marine A, Verbeek J. Systematic review of interventions for reducing occupational stress in health care workers. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health. 2008:169–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodenheimer T, Chen E, Bennett HD. Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: can the US health care workforce do the job? Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):64–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens S. Five year forward view. London: NHS England; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black C. Working for a healthier tomorrow. Department for Work and Pensions; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(6):573–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The Quadruple Aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corrigan JM, Adams K, Greiner AC. 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit:: A Focus on Communities: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Workforce and Facilities Team Health and Social Care Information Centre. NHS Sickness Absence Rates January 2014 to March 2014 and Annual Summary 2009–10 to 2013–14. London: Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2014.

- 15.Schaufeli W. Past performance and future perspectives of burnout research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology. 2003;29(4):p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poland B, Krupa G, McCall D. Settings for health promotion: an analytic framework to guide intervention design and implementation. Health Promotion Practice. 2009;10(4):505–16. doi: 10.1177/1524839909341025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boorman S. The Final Report of the independent NHS Health and Well-being review,. London: TSO: Department of Health; 2009.

- 18.Department of Health. NHS health and well-being improvement framework. London: TSO: Department of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: 2009. 1900640473. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [webpage on the Internet] Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. [cited 2017 June 12]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group. Data collection checklist. Ontario: University of Ottawa; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorensen G, Stoddard A, Peterson K, Cohen N, Hunt MK, Stein E, et al. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption through worksites and families in the treatwell 5-a-day study. American journal of public health. 1999;89(1):54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jasperson DB. RadSurg wellness program: improving the work environment and the workforce team. Radiology management. 2009;32(1):48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess I, Borg J, Rissel C. Workplace nutrition and physical activity promotion at Liverpool Hospital. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 2011;22(1):44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McElligott D, Capitulo KL, Morris DL, Click ER. The effect of a holistic program on health-promoting behaviors in hospital registered nurses. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2010;28(3):175–83. doi: 10.1177/0898010110368860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blake H, Zhou D, Batt ME. Five-year workplace wellness intervention in the NHS. Perspectives in public health. 2013;133(5):262–71. doi: 10.1177/1757913913489611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemon SC, Zapka J, Li W, Estabrook B, Rosal M, Magner R, et al. Step ahead: a worksite obesity prevention trial among hospital employees. American journal of preventive medicine. 2010;38(1):27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchiyama A, Odagiri Y, Ohya Y, Takamiya T, Inoue S, Shimomitsu T. Effect on Mental Health of a Participatory Intervention to Improve Psychosocial Work Environment: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial among Nurses. Journal of occupational health. 2013;55(3):173–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dobie A, Tucker A, Ferrari M, Rogers JM. Preliminary evaluation of a brief mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for mental health professionals. Australasian Psychiatry. 2016;24(1):42–5. doi: 10.1177/1039856215618524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wieneke KC, Clark MM, Sifuentes LE, Egginton JS, Lopez-Jimenez F, Jenkins SM, et al. Development and impact of a worksite wellness champions program. American journal of health behavior. 2016;40(2):215–20. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.40.2.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun X Z Nan; Liu Kun; Li Wen; Oksanen Tuula; Shi Lizheng. Effects of a Randomized Intervention to Improve Workplace Social Capital in Community Health Centers in China. PLOSONE. 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

Data are all from published research articles that are available by using the references in the manuscript.