The ability to detect pleiotropy has important biological applications, but there is a lack of rigorous tests available. One exception is a recent test..

Keywords: GEE, likelihood ratio test, multiple-trait association testing, structural equation models, union-intersection test, Wald test

Abstract

There is growing interest in testing genetic pleiotropy, which is when a single genetic variant influences multiple traits. Several methods have been proposed; however, these methods have some limitations. First, all the proposed methods are based on the use of individual-level genotype and phenotype data; in contrast, for logistical, and other, reasons, summary statistics of univariate SNP-trait associations are typically only available based on meta- or mega-analyzed large genome-wide association study (GWAS) data. Second, existing tests are based on marginal pleiotropy, which cannot distinguish between direct and indirect associations of a single genetic variant with multiple traits due to correlations among the traits. Hence, it is useful to consider conditional analysis, in which a subset of traits is adjusted for another subset of traits. For example, in spite of substantial lowering of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) with statin therapy, some patients still maintain high residual cardiovascular risk, and, for these patients, it might be helpful to reduce their triglyceride (TG) level. For this purpose, in order to identify new therapeutic targets, it would be useful to identify genetic variants with pleiotropic effects on LDL and TG after adjusting the latter for LDL; otherwise, a pleiotropic effect of a genetic variant detected by a marginal model could simply be due to its association with LDL only, given the well-known correlation between the two types of lipids. Here, we develop a new pleiotropy testing procedure based only on GWAS summary statistics that can be applied for both marginal analysis and conditional analysis. Although the main technical development is based on published union-intersection testing methods, care is needed in specifying conditional models to avoid invalid statistical estimation and inference. In addition to the previously used likelihood ratio test, we also propose using generalized estimating equations under the working independence model for robust inference. We provide numerical examples based on both simulated and real data, including two large lipid GWAS summary association datasets based on ∼100,000 and ∼189,000 samples, respectively, to demonstrate the difference between marginal and conditional analyses, as well as the effectiveness of our new approach.

THERE has been a growing interest in testing genetic pleiotropy, which is when a single genetic variant (or gene) influences multiple traits (Solovieff et al. 2013). As pointed out by Schaid et al. (2016), detecting pleiotropy may shed light on the underlying biological mechanism of a genetic association, with important implications for therapeutic development, such as drug repurposing. Testing pleiotropy can be also useful in checking an assumption (i.e., no pleiotropic effects of a genetic instrument variable on both a risk factor/exposure and an outcome) imposed by Mendelian randomization for causal inference. There is accumulating empirical evidence to support pervasive pleiotropy for complex diseases and traits (Cotsapas et al. 2011; Q. Wang et al. 2015). Leveraging pleiotropy in GWAS with multiple traits may boost statistical power in detecting genetic associations (Chung et al. 2014) as well as improving genetic risk prediction (Li et al. 2014). Most existing methods for analysis of multiple traits test on a global null hypothesis that none of the traits is associated with a genetic variant, which, if rejected, cannot tell whether the genetic variant is associated with only one or with two or more traits (e.g., Y. Wang et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2016; Z. Wang et al. 2016 and references therein). In pleiotropy testing, the target of interest is not the global null hypothesis, but rather that the genetic variant is associated with no more than one trait. A simple approach would first conduct a univariate association test on each trait separately, then check whether two or more P-values are significant after a proper multiple testing adjustment. As shown in a later example, this naïve approach is often too low powered due to the univariate nature of this test. Accordingly, some methods have been developed to test pleiotropy. Cotsapas et al. (2011) developed a cross-phenotype meta-analysis (CPMA) method to test pleiotropy using summary statistics, which seems straightforward, but requires that we already know of the existence of one significant association, which may not be practical. In addition, it imposes a strong parametric assumption on the distribution of the marginal association P-values under the alternative hypothesis, which may lead to loss of power when the assumption does not hold. Alternatively, other methods explore which of the multiple traits are associated (Stephens 2013; Majumdar et al. 2016). Schaid et al. (2016) not only nicely surveyed existing methods, but also proposed a new and rigorous pleiotropy test based on the intersection-union testing approach (Berger 1997) with individual-level genotype and phenotype data. However, Schaid et al. (2016) focused mainly on the marginal analysis of each trait (with possible covariates). Sometimes, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) might influence a trait through some intermediate traits, which means the effect on the trait is indirect. It is well-known that marginal analysis cannot distinguish direct and indirect effects. In contrast, conditional analysis can, and thus might be more useful. For example, although low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol remains the primary treatment target to reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, it has been shown that high triglyceride (TG) level is a possible independent risk factor for CVD, even in patients with treatment-controlled LDL levels (Boekholdt et al. 2012; Sampson et al. 2012; Do et al. 2013; Toth 2016). Hence, to identify new targets for new therapy to reduce levels of TG or other non-LDL lipids, it is more desirable to detect genetic variants associated with TG and non-LDL lipids after adjusting for LDL; otherwise, due to the known correlations among various lipids, an identified association, say with TG, could simply be due to an indirect effect through LDL.

Importantly, since we most often have summary association statistics only from meta- or mega-analyzed large genome-wide association study (GWAS) data, rather than individual level data, it would be useful to have a pleiotropy test applicable to GWAS summary statistics. With these considerations, we first propose extending the likelihood-ratio test (LRT) of Schaid et al. (2016) with individual-level data to that with only summary statistics for marginal analysis with possible covariates (i.e., exogenous variables). Next, for either individual-level GWAS data or summary statistics, we develop a new testing procedure for conditional analysis with some traits as both responses and predictors in multiple conditional regression equations; care has to be taken in this extension to avoid biased estimation and inference. To test a composite null hypothesis, we adopt the union-intersection testing strategy as used in Schaid et al. (2016). In particular, we consider conditional regression equations with some traits as both responses and predictors, for which, in addition to extending the LRT of Schaid et al. (2016), for simplicity and robustness, we propose using the Wald test in generalized estimating equations (GEE) with the working independence model.

We will use simulations to show the feasibility of marginal or conditional analysis with summary statistics as well as the difference between marginal and conditional analyses. We will also apply the methods to real data to further demonstrate these points.

Methods

Marginal analysis with individual level data

In this section, we give a brief review of the pleiotropy test of Schaid et al. (2016). Throughout this paper, a marginal analysis is defined as one in which no proper subset of traits is used as response in some regression models and as covariate in some other regression models. Hence, a marginal analysis allows the adjustment for nontrait covariates like multiple SNPs. Correspondingly, a conditional analysis is based on multiple regression models including some traits as both responses and covariates.

Suppose that the individual level data contain traits and SNPs (or other covariates) for subjects. As mentioned by Schaid et al. (2016), the covariates may be either trait-varying or not trait-varying. For simplicity, we just assume the same SNPs across different traits. Let denote the measured th trait, and denote the th SNP for all subjects. Assume they are all centered at 0.

The regression model can be expressed as

where

is a identity matrix, is the Kronecker product, and the matrix is the covariance matrix for the errors within subjects. All the SNPs are adjusted for in this model.

Suppose the null hypothesis is : at most one of the parameters ..., is nonzero. It is equivalent to test whether one of the following tests holds:

Let be a matrix. Denote the matrix obtained after deleting the th row of by Then, is equivalent to Schaid et al. (2016) proposed using the test statistic

where and Use ordinary least squares to estimate and then can be estimated using the residuals.

According to Schaid et al. (2016), is the LRT statistic for

Since the null distribution of is complicated, they tested in two stages. The first stage uses and the second stage uses

asymptotically follows when asymptotically follows when only one of ..., is nonzero. Reject only if and

Marginal analysis with summary statistics

In this section, we describe a few steps to calculate the previous test statistics based only on GWAS summary statistics.

-

If we have each the marginal effect of on and its variance as well as some reference panel and summary statistics of null SNPs (i.e., not associated with any traits), we can estimate and If we only have Z-statistics, we can regard them as ’s and assume This approach turns out not to influence the result for marginal analysis, but may change the result for conditional analysis.

1a. Suppose we have individual level data centered at 0 from some reference panel for the SNPs of interest, where is the th SNP for subjects. We can estimate by and by Note that multiplying by a constant does not affect the test results, so we do not really have to use the scalar For marginal analysis with only one SNP, we can simply assume is 1.

- 1b. Estimate using

where we plug in our estimate of as

- 1c. Suppose we have Z-statistics for marginal analysis of with many null SNPs. We can estimate as when using the idea of Kim et al. (2015) and Kwak and Pan (2016, 2017) that

- 1d. Estimate using

-

Estimate the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimate Note that the OLS estimate and the GLS estimate are the same when there is no trait-specific covariate, which is true in our current scenario. The formula is simply

- and can be obtained by

-

Estimate from the residuals. can be expressed as

- where and By simple algebra, we have

Thus, we can obtain using and Then is simply

-

Now we only need to know and By simple algebra, and replacing with we have

- where is the th entry of Finally, we can calculate the statistics

The remaining testing procedure is the same as that in the previous section.

Conditional analysis with LRTs

For conditional analysis, we consider adjusting for a proper subset of the traits in the regression models for another (nonintersecting) subset of the traits as the responses. The derivation of the above LRT can still be carried out. If we have individual level data, the original method of Schaid et al. (2016) should allow incorporation of some traits as trait-specific covariates, though their R package “pleio” allows taking only one SNP without any other covariates. If we only have summary statistics, similar to what was done in Deng and Pan (2017), we can follow the previous idea to derive a similar procedure.

Now, the matrix notation we use is

is the same as before, while

Thus, is a design matrix combining the information of and is a refined version of with columns.

is a matrix obtained by deleting the th, th, ..., th columns of an identity matrix of order The purpose of multiplying by is to delete the corresponding columns of so that the model will be instead of

Denote the effect of the th SNP on the th trait by and the th trait on the th trait by Vector is dimensional.

The detailed testing procedure is described below.

Now the test statistic is

where Besides, in the new scenario, is rather than We only need to add zeros to the right of the previous

Following the previous procedure, we can get ’s using a few steps:

Estimate and using the summary statistics, reference panels, and null SNPs. The procedure is described in point (1) in the previous section.

-

Estimate the OLS estimate by

- Denote by and by and can be obtained by

- Following ideas similar to those presented above, we can easily get

-

Estimate from the residuals. can be expressed as

- where and Here, includes both SNPs and traits. Note that while ’s are dimensional vectors obtained by adding a 0 element between the th and th elements of ’s. Hence, we can get from By simple algebra, we have

Thus we can obtain using and Then, is simply

-

Again, we only need to know and By simple algebra, and replacing with we have

- where is the th entry of As for we can derive

Hence, we can get everything we need as long as we can estimate and These estimates are obtained in step (1).

We can modify the model with a different form of One model we are interested in is To fit this model, we let be a matrix. It is obtained by combining the first columns of an identity matrix of order with columns where Following this notation, vector becomes where

Our specified model for conditional analysis is a so-called recursive system: (1) it contains a hierarchical model with some traits as predictors for other traits, but not otherwise, and (2) the error terms in the different regression equations are independent; the OLSE is unbiased for a recursive system (Hanushek and Jackson 1977, p. 229).

Conditional analysis with GEE-based Wald tests

The LRT depends critically on the Normality assumption, which may be violated. Instead, we propose using GEE for its much weaker assumptions: for large samples, it depends only on the correct specification of the regression models for the mean function of the traits, but not even on the correct specifications of the variance-covariance matrix of the traits. We propose conducting a union-intersection test with the Wald test in GEE with a working independence model; that is, instead of the GLSE and LRT, we propose using the OLSE and the corresponding sandwich covariance matrix estimate for valid inference.

Using the previous notation, we define the sandwich covariance estimator and the naive covariance estimator as

where is the estimated variance of the error terms for the naive model, which assumes the error terms are identically independently distributed.

The new testing procedure includes a few steps.

Estimate and using the summary statistics, reference panels, and null SNPs.

Obtain the OLS estimate

Estimate and from the residuals. The procedure is the same as step 3 in the previous section.

-

Calculate the sandwich covariance matrix estimate

- where can be obtained in the same way as we did in the previous section, and can be derived by

For the naive method, we can simply use to estimate where is the sum of the diagonal elements of By simple algebra, is indeed the sum of squared errors for the naive model.

-

The test statistics are

We reject only if and If we want to apply the naive method instead, replace with

Note that this method can also be applied to the analysis adjusting for a few SNPs only, or only for a subset of traits, or their combination. We may extend the methods to sequential tests of multiple associated traits as discussed in Schaid et al. (2016) in the future.

Dealing with different samples

Sometimes the summary statistics for different traits may be based on completely different samples (i.e., no overlapping subjects). We can modify the Wald test to carry out the corresponding pleiotropy testing. There are two possible ways.

Approach 1:

Note that the OLS estimates for the joint model of all traits vs. SNPs are the same as OLS estimates for separate models of each trait vs. SNPs. Also, since different traits are obtained from different subjects, they are independent, meaning that should be diagonal. The th diagonal element of should simply be the estimated variance of the error term in the regression model for trait vs. SNPs, which can be calculated by where is the sum of squares of X for the th sample (the sample for getting marginal effects on trait ). We can estimate by assuming is proportional to the sample size. Since the scale of X does not affect the result, we can simply set to be 1.

Approach 2:

Assume different samples with sample sizes are obtained by a random partition of a whole sample with sample size Build the joint model for all subjects so that we do not need to change our previous model. We can assume that based on all subjects is the same as that based on just subjects (when the sample size is large). Now where and are the and for subjects. We can also assume for all subjects is approximately approximately As a result, we still have Hence, we do not need to modify any formulas. We just need to input as

The two approaches address two different questions. Take a simple example with two traits and one SNP Suppose subjects were taken to obtain the summary statistics for vs. and different subjects were used to calculate the summary statistics for vs. For the first approach, the alternative hypothesis is that is associated with the two populations, from which the subjects (for ) and the subjects (for ) were drawn respectively, allowing the two sets of subjects to come from two, possibly different, populations. Rejecting the null hypothesis does not guarantee that is also associated with the first population’s second trait However, for the second approach, the alternative hypothesis is that influences both and assuming all the subjects came from the same population. Hence, the results of the two approaches may be different if the study populations for different traits are indeed different. Nevertheless, in our opinion, the second approach is preferred under the common assumption that the study populations are the same, since it can then tell whether a SNP is indeed associated with more than one trait for the same population, which follows the definition of pleiotropy. Of course, in the second approach we have to assume a common population, which may be violated in practice.

Data availability

The Cotsapas dataset can be downloaded from the online version of Cotsapas et al. (2011). The 2010 (Teslovich et al. 2010) and 2013 (Willer et al. 2013) lipid data are also publicly available at http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/public/lipids2010 and http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/public/lipids2013/, respectively. The R package for our new methods is publicly available at Github: https://github.com/yangq001/Plei.

Results

Simulations for marginal analysis

To see whether the marginal analysis using summary statistics can control Type-I errors, we conducted simulations similar to those presented in Schaid et al. (2016). In the simulations, only a single SNP with minor allele frequency (MAF) 0.2 was used. The traits were generated from multivariate normal distributions. The variances of the error terms was all 1’s with an exchangeable correlation structure with correlation

Since our method only uses summary statistics, we also generated 1000 null SNPs with the same sample size to estimate the correlation between the traits. We centered the data, and performed a univariate association analysis. Then, we applied our method to the resulting summary statistics. To estimate the rejection rates, we used 1000 replications under each setting.

Now the true model (for set-up A) is

where the diagonal elements of are all 1’s and the other elements are The fitted model for marginal analysis can be simply expressed as

First, we considered the case when only one trait is associated with the SNP. According to Table 1, all methods had similar performances in terms of type I errors. The results were also close to those in Schaid et al. (2016). For convenience, we denote the various analysis methods as:

Table 1. Type I errors for set-up A with .

| Sample size | # Traits | Nominal type-I ER = 0.05 | Nominal type-I ER = 0.01 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | |||

| 500 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| 0.5 | 0.044 | 0.046 | 0.043 | 0.046 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.015 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.051 | 0.048 | 0.050 | 0.048 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | ||

| 10 | 0.2 | 0.056 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.054 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.012 | |

| 0.5 | 0.056 | 0.052 | 0.051 | 0.052 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.014 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.055 | 0.053 | 0.052 | 0.053 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.015 | ||

| 1000 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| 0.5 | 0.039 | 0.041 | 0.039 | 0.041 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.009 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.042 | 0.046 | 0.042 | 0.046 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | ||

| 10 | 0.2 | 0.056 | 0.060 | 0.055 | 0.060 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 | |

| 0.5 | 0.056 | 0.059 | 0.056 | 0.059 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.013 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.056 | 0.053 | 0.054 | 0.053 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.015 | 0.012 | ||

LRT-Ind: the original LRT of Schaid et al. (2016) with individual level data as implemented in R package “pleio.”

LRT-Sum: the LRT with summary statistics.

Wald-Ind: the GEE-based Wald test with individual level data (to calculate X’X and correlations between traits).

Wald-Sum: the GEE-based Wald test with summary statistics; using a reference panel and some null SNPs to calculate X’X and correlations between traits.

Next, we considered the case when no trait is associated with the SNP (set-up B). Again, as shown in Table 2, all the methods performed similarly. They seemed to be conservative in this case, which is expected. Recall that the pleiotropy tests are like two-stage tests, and the first stage is the overall test of nonassociation, which should have a rejection rate of 0.05 (or 0.01) under this setting. The rejection rate of the combined tests is <0.05 (or 0.01), since, to reject pleiotropy, both the overall test and the second-stage test must reject their respective null hypothesis. As a result, all these pleiotropy tests turn out to be conservative, as shown in Schaid et al. (2016).

Table 2. Type I errors for set-up B with .

| Sample size | # Traits | Nominal type-I ER = 0.05 | Nominal type-I ER = 0.01 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | |||

| 500 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| 0.5 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 10 | 0.2 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 | ||

| 1000 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.5 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 10 | 0.2 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.5 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

To compare statistical power of the various methods, we let some associated traits have a nonzero effect size of 0.25. The sample size was 500, and the number of traits was 10. As shown in Table 3, the new methods performed similarly to the original methods using individual level data.

Table 3. Power.

| # Associated traits | Nominal type-I ER = 0.05 | Nominal type-I ER = 0.01 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | ||

| 2 | 0.2 | 0.465 | 0.447 | 0.441 | 0.449 | 0.223 | 0.203 | 0.206 | 0.208 |

| 0.5 | 0.772 | 0.752 | 0.749 | 0.744 | 0.516 | 0.491 | 0.490 | 0.499 | |

| 3 | 0.2 | 0.845 | 0.835 | 0.829 | 0.835 | 0.647 | 0.618 | 0.621 | 0.624 |

| 0.5 | 0.980 | 0.979 | 0.975 | 0.977 | 0.927 | 0.916 | 0.915 | 0.914 | |

| 5 | 0.2 | 0.980 | 0.979 | 0.979 | 0.981 | 0.943 | 0.933 | 0.937 | 0.938 |

| 0.5 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.994 | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.990 | |

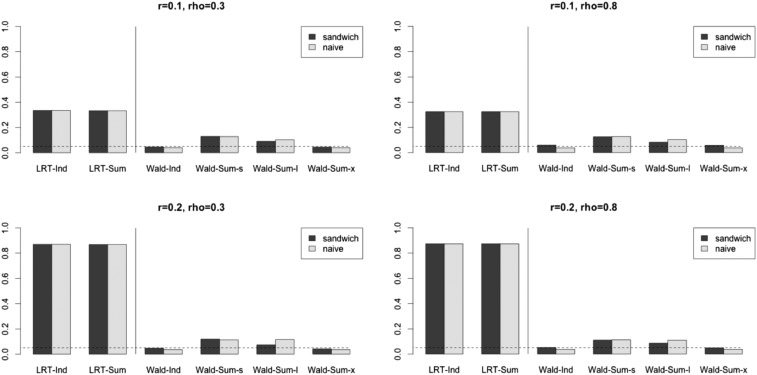

Under the first simulation setting, we also carried out the Wald test in GEE (under the working independence model) using the naive covariance estimate, instead of the sandwich covariance estimate. As shown in Figure 1, as expected, this approach, denoted Wald-N, led to inflated type I errors when the error terms were strongly correlated (as the working independence model did not hold). Hence, we recommend using the sandwich covariance.

Figure 1.

Type I errors in simulation set-up A with Wald-N denotes the GEE Wald test using individual level data and the naive covariance matrix estimate; 1000 null SNPs were generated once for analysis with summary statistics. We used 1000 replications to calculate the rejection rates. A nominal significance level of 0.05 is marked by a dashed line.

The above cases included only one SNP. To be more general, we considered a simple scenario with two SNPs, both with MAF 0.2. The correlation between the SNPs is r. We generated the traits using the true model

After centering the simulated data, we obtained the summary statistics and conducted analysis adjusting for SNPs. For comparison, we also did an “unadjusted” marginal analysis with only SNP 1. We aimed to test for pleiotropy for SNP 1.

For the methods using only summary statistics, to estimate the correlation of the traits, we generated 1000 null SNPs and obtained their Z-scores by regressing each trait on each null SNP. In addition, we generated SNPs for subjects using MAF 0.2 and correlation r. These were used to estimate For each replication, a new reference dataset was generated.

Now the fitted models are for the “unadjusted” marginal analysis, and are for “adjusted” marginal analysis, where each includes the two traits. We considered three versions of the Wald-Sum test:

Wald-Sum-s: using summary statistics and reference data.

Wald-Sum-l: using summary statistics and reference data.

Wald-Sum-x: using summary statistics and true

Based on Figure 2, it appears that the unadjusted marginal analyses had the highest type I error rates. This is expected because SNP 1 is associated with trait 1, and trait 1 and trait 2 are correlated. As a result, SNP 1 is also marginally associated with trait 2, leading to that the unadjusted marginal analyses rejects the null hypothesis. Our adjusted marginal analysis using summary statistics and true could control type I errors, but using estimates from reference data resulted in inflated type I errors. The reason was that the estimated and the true were different. Note that Wald-Ind and Wald-Sum-x almost had the same results, suggesting that using the null SNPs to estimate was sufficient.

Figure 2.

Type I errors with and a nominal significance level of 0.05.

Next, we also looked at the power of different methods. According to Figure 3, as expected, the adjusted methods were more conservative than the unadjusted methods when had the same sign as since the adjusted methods could control the type I errors. When we changed the sign of the power of the unadjusted marginal analysis became very low, while the adjusted marginal analysis could maintain its power. Our explanation for this phenomenon is that, when two SNPs are positively correlated but have effects on the trait in different directions, their marginal effects will be diluted, so the unadjusted marginal analysis is less likely to detect pleiotropy. Note that, using the sandwich covariance and the naive covariance, matrix estimates performed similarly in the above settings, even though the two traits were correlated.

Figure 3.

Power with and a nominal significance level of 0.05.

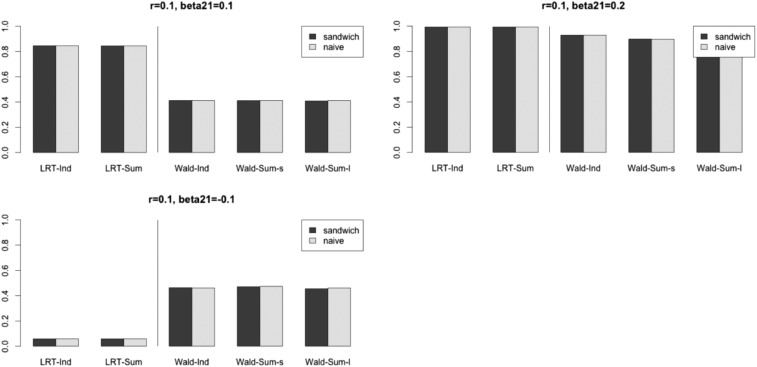

Simulations for conditional analysis

Consider a situation with one SNP and two traits. We generated one SNP with MAF 0.2. The true model is

where ’s () are independent normal random variables with mean 0 and variance 1 (and correlation 0).

Now the fitted model for marginal analysis is For conditional analysis, the model is We examined the estimated type I errors and power of marginal analysis and conditional analysis. Denote the GEE-based Wald tests by Wald-Ind-N and Wald-Sum-N after replacing the sandwich covariance matrix estimate with the naive covariance matrix estimate.

As shown in Table 4, all the methods could control type I errors. As expected, replacing the sandwich covariance estimate by the naive covariance estimate did not really influence the result; since the error terms were uncorrelated, the working independence model used in GEE held, leading to the good performance of the naïve covariance estimate.

Table 4. Type I errors with .

| Nominal significance level = 0.05 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal | Conditional | ||||||||

| LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | Wald-Ind-N | Wald-Sum-N | ||

| 0 | 0.3 | 0.042 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.040 |

| 0.6 | 0.042 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.040 | |

| 0.9 | 0.042 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.040 | |

| 1.2 | 0.042 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.041 | 0.040 | 0.040 | |

10,000 null SNPs were generated once for methods with summary statistics.

As shown in Table 5, all methods gave similar power in this case. We noticed that, when > increasing did not increase the power. One possible explanation is that, in this situation, the pleiotropy tests largely depend on whether is significant. The overall test and the test for are almost always significant, so only the test for influences the combined test. When is increased, the estimates of and its SE do not change much for marginal analysis, so the power does not improve. Sometimes, the estimated SE for may become larger, making the test for less likely to reject the null. The extent of this is slightly greater for the conditional model. As a result, the conditional methods may even lose a little power.

Table 5. Power with .

| Nominal significance level = 0.05 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal | Conditional | ||||||

| LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | Wald-Ind-N | Wald-Sum-N | ||

| 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.416 | 0.416 | 0.416 | 0.415 | 0.414 | 0.414 |

| 0.6 | 0.416 | 0.416 | 0.416 | 0.415 | 0.414 | 0.414 | |

| 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.955 | 0.952 | 0.956 | 0.955 | 0.952 | 0.952 |

| 0.6 | 0.955 | 0.953 | 0.956 | 0.955 | 0.952 | 0.952 | |

In another scenario, suppose the SNP has an indirect effect on one trait through another trait. Now the model we use to simulate traits is

where ’s () are bivariate normal random variables with variance 1 and correlation 0. They are independent of the SNP.

Again we centered the data and conducted different ways of analysis. The fitted model for marginal analysis is For conditional analysis, the model is

As shown in Table 6, the new methods could control type I errors when using individual level data, but might have slightly inflated type I error rates when using summary statistics. In contrast, the marginal analysis could not control type I errors at all. Again, using the naive covariance or the sandwich covariance estimate did not matter in this case.

Table 6. Type I errors with .

| Nominal significance level = 0.05 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRT-Ind | LRT-Sum | Wald-Ind | Wald-Sum | ||

| 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.335 | 0.335 | 0.047 | 0.048 |

| 0.6 | 0.808 | 0.807 | 0.047 | 0.050 | |

| 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.882 | 0.882 | 0.049 | 0.059 |

| 0.6 | 1 | 1 | 0.049 | 0.058 | |

1000 null SNPs were generated once for methods with summary statistics. We used the true correlation matrix to estimate and 3000 replications to calculate the rejection rates.

The Cotsapas data

We looked at the data offered by Cotsapas et al. (2011). The dataset contains marginal Z-scores of 107 SNPs on each of seven autoimmune diseases: celiac disease (CeD), Crohn’s disease (CD), multiple sclerosis (MS), psoriasis (Ps), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and type 1 diabetes (T1D). The original paper found many SNPs with pleiotropy using their proposed CPMA. For comparison, we applied various pleiotropy tests.

Note that this dataset does not contain SE, so we took the Z-scores as effect sizes and assumed the SE was 1. In addition, the summary statistics for different traits used different samples, so we could apply the two approaches discussed earlier for the Wald method.

We applied different approaches to the Cotsapas data (107 SNPs, seven traits). First, we assumed we already knew that each SNP was significant for one specific trait. Then, we tested whether more traits were associated, and compared the result with CPMA. Then, we tested pleiotropy without that assumption.

As shown in Table 7, our proposed Approach 2 detected more SNPs with pleiotropy, and covered most of the significant SNPs identified by CPMA. In this situation with marginal analysis, the Wald test and the LRT gave very similar results. When we directly applied CPMA “without assumption,” 93 SNPs became significant, which, however, were obtained because, in this case, CPMA was testing whether there was at least one association, not necessarily pleiotropy.

Table 7. Numbers of significant SNPs (P-value <0.01).

| CPMA | LRT-Sum with Approach 2 (overlap) | Wald-Sum with Approach 1 (overlap) | Wald-Sum with Approach 2 (overlap) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With assumption | 47 | 57 (46) | 48 (47) | 57 (46) |

| Without assumption | 52 (43) | 46 (45) | 52 (43) |

“With assumption”: assuming each SNP is already known to be significant for one trait, then testing whether there is at least one more significant association; “Without assumption”: directly testing whether there are at least two significant associations for each SNP; “Overlap”: the numbers of the significant SNPs that are also among the 47 detected ones by CPMA (“With assumption”).

The lipid data

The Global Lipids Genetics Consortium GWAS study (Willer et al. 2013) has shown many loci associated with more than one trait among LDL, HDL, TG and TC. To study this further, we conducted pleiotropy tests for single SNPs. We applied the methods to two summary association datasets based on ∼100,000 and ∼189,000 subjects, respectively (Teslovich et al. 2010; Willer et al. 2013), which we call the 2010 and 2013 data, respectively. The 2013 data are an expanded version of the 2010 data with more study subjects.

First, following the idea of Kim et al. (2015), we used the Z-scores of 2,371,319 nonsignificant SNPs for all traits from the 2013 data to estimate the correlations among the four types of lipids, confirming their moderate to high correlations, which imply possible differences between marginal and conditional analyses. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Estimated correlations between the lipid traits.

| TG | LDL | HDL | TC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG | 0.228 | −0.414 | 0.324 | |

| LDL | −0.087 | 0.873 | ||

| HDL | 0.138 |

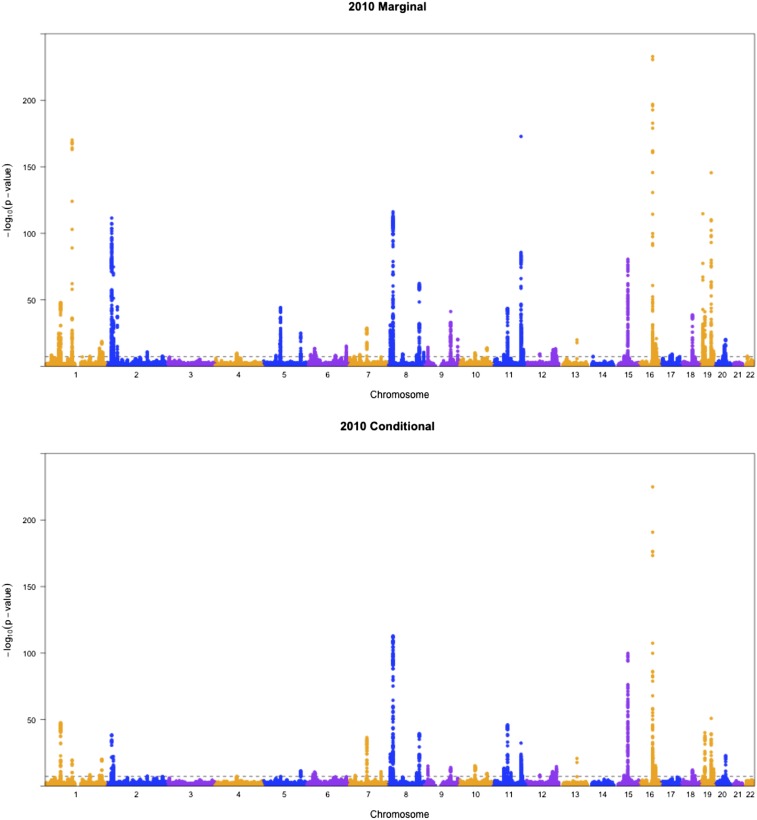

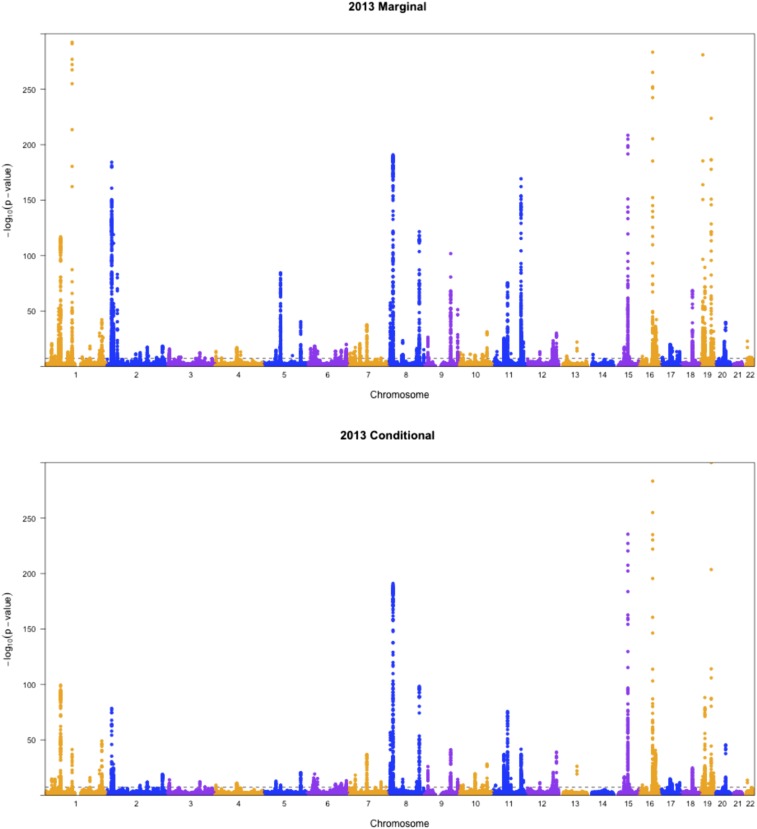

Next we conducted a genome-wide scan on each dataset. We tested pleiotropy for 2,363,472 SNPs that are included in both 2010 Lipids data and 2013 Lipids data. These SNPs are also present in the 1000 Genomes Project data (The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. 2015). We applied both marginal analysis and conditional analysis. As some previous studies have shown, LDL-lowering treatments might increase the risk of type 2 diabetes partly due to their ontarget mechanisms (Swerdlow et al. 2015; Hemani et al. 2016). It might be useful to identify new drug targets by identifying genetic variants with pleiotropic effects on non-LDL lipids. To exclude the indirect effects of a genetic variant through LDL, we chose to conduct a conditional analysis of other lipids after adjusting for LDL. The marginal model is

In contrast, the conditional model is

Note that a pleiotropic effect detected by marginal analysis could be due to indirect effect through LDL: for example, if an SNP is causal for high LDL but not for any other three traits, then, by the correlations among the traits, it will be marginally associated with all the traits. However, with the conditional model, we can avoid such false positives; we aim to test for pleiotropic effects after adjusting for LDL, which may help identify new targets for new drugs as alternatives to LDL-lowering drugs like statin. The null hypothesis for both marginal and conditional pleiotropic tests is that none, or only one, of and is nonzero.

To show the difference between conditional analysis and marginal analysis, we generated some Manhattan plots. As shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, generally the results from 2010 data and 2013 data agreed with each other, except that the latter results seemed more statistically significant, which is expected given the larger sample size of the 2013 data. Interestingly, most SNPs that were highly significant in marginal analysis became less significant in conditional analysis, which means that part of their associations might be indirect through LDL as an intermediate. Take SNP rs10043960 on chromosome 5 as an example. The P-value for the pleiotropy test in marginal analysis was while it became nonsignificant at 0.74 after adjusting for LDL.

Figure 4.

Manhattan plots for pleiotropic testing with the 2010 lipid data.

Figure 5.

Manhattan plots for pleiotropic testing with the 2013 lipid data.

Note that if the conditional model is true, and which means the SNP does not affect TC directly, then As a result, the coefficient in the marginal model should be Also notice that and If we assume (which may or may not hold since we do not have individual-level data to verify,) then we have suggesting that the estimated marginal effect should be approximately equal to the product of the estimated conditional effect and the correlation between the two traits. For SNP rs10043960, the marginal effect sizes on TG, LDL, HDL, and TC were 0.0096, 0.0402, −0.0050, and 0.0401, respectively. If we multiply the effect size on LDL by the estimated correlation between LDL and each of the other traits (shown in Table 8), we get 0.0092, −0.0035, and 0.0351 for TG, HDL, and TC, which are close to the estimated marginal effects. This may suggest that indirect effects through LDL can explain the marginal effects of the SNP on TG, HDL, and TC.

Meanwhile, the significance levels of some SNPs did not change, or even increased after adjusting for LDL. For SNP rs7259679 on chromosome 19, the P-value for marginal pleiotropic effects was while the conditional P-value was The sign of the effect on LDL and the signs of the effects on TG and TC were opposite, while the estimated correlations between LDL, and TG and TC were positive and not small, which resembles the special case discussed above (Table 5). The true effects on LDL, TG, and TC were very likely to be larger than the marginal effects. As a result, the conditional method detected pleiotropy by looking at the true effects, while the marginal method did not.

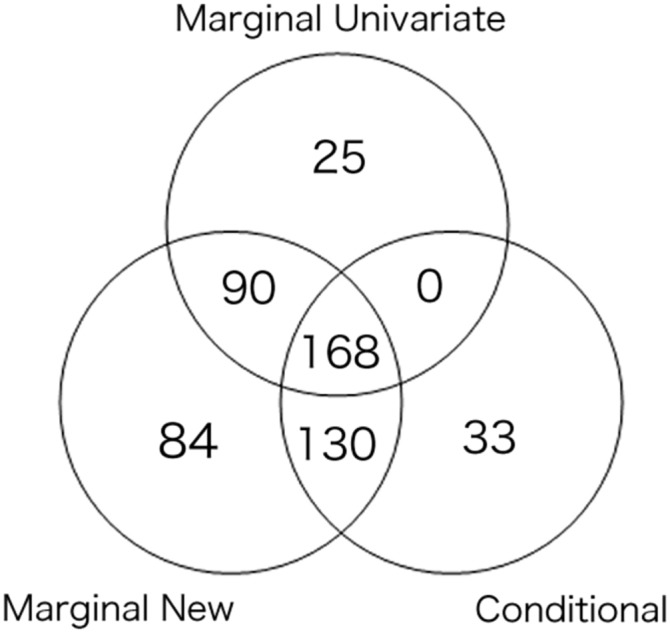

A simple (and perhaps popular) way to conduct marginal analysis is to look at the marginal P-values for each SNP vs. each trait. If a SNP has at least two significant P-values, we reject the null hypothesis of no pleiotropy. Since this approach involves multiple testing across multiple traits, we apply the Bonferroni adjustment, leading to a genome-wide significance threshold of 5e−8 divided by the number of traits (i.e., four here). To distinguish this from the marginal analysis described in the previous sections, called “marginal, new,” we call this univariate/single trait testing-based method “marginal, univariate.” Next, we mapped the significant SNPs to loci for each analyses, following the same procedure as used by Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium et al. (2014). As shown in Figure 6, most of the loci detected by “marginal univariate” analysis were recovered by the new marginal test, while the latter found many more significant loci. The results of conditional analysis and marginal analysis differed, which might suggest that the effects of certain loci on some traits were indirect, with LDL as an intermediate.

Figure 6.

The numbers of the significant loci with pleiotropy detected by the three methods.

Discussion

We have presented new tests for genetic pleiotropy based on either marginal analysis or conditional analysis using summary statistics. For marginal analysis with only nontrait covariates (i.e., exogenous variables), we extend and apply the LRT of Schaid et al. (2016). For conditional analysis with some traits as both responses and predictors (i.e., endogenous variables), in addition to extending the LRT of Schaid et al. (2016), for robustness, we also propose using the Wald test in GEE with the working independence model and its corresponding sandwich covariance matrix estimate. Note that we assume a recursive system, for which the OLSE (i.e., GEE estimator with the working independence model) is unbiased (Hanushek and Jackson 1977, p. 229); more general structural equation models (Li et al. 2006; P. Wang et al. 2016) may require a two-stage least squares estimator, which is much more complex and, more importantly, it is unclear whether it can be applied to summary statistics only. Our extensive simulations showed that our conditional method performed better than marginal analysis in terms of controlling type I errors when indirect effects existed. In some cases, the conditional analysis even had higher power than the marginal analysis. Marginal analysis adjusting for SNPs is also better than unadjusted marginal analysis in certain cases. We applied our methods to the Cotsapas data, and found more SNPs with genetic pleiotropy, covering most of those detected by Cotsapas et al. (2011). We also applied different approaches to the 2010 and 2013 lipid data to show possible differences between marginal and conditional analyses.

In the future, we may extend our methods to sequential tests of multiple associated traits as discussed in Schaid et al. (2016).

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and reviewers for many detailed and helpful comments. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01GM113250, R01HL105397, R01HL116720, and R21AG057038, and by the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute at the University of Minnesota.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: E. Eskin

Literature Cited

- Berger R. L., 1997. Likelihood ratio tests and intersection-union tests, pp. 225–237 in Advances in Statistical Decision Theory and Applications. Birkhäuser, Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Boekholdt S. M., Arsenault B. J., Mora S., Pedersen T. R., LaRosa J. C., et al. , 2012. Association of LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B levels with risk of cardiovascular events among patients treated with statins: a meta-analysis. JAMA 307: 1302–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung D., Yang C., Li C., Gelernter J., Zhao H., 2014. GPA: a statistical approach to prioritizing GWAS results by integrating pleiotropy and annotation. PLoS Genet. 10: e1004787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotsapas C., Voight B. F., Rossin E., Lage K., Neale B. M., et al. , 2011. Pervasive sharing of genetic effects in autoimmune disease. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Pan W., 2017. Conditional analysis of multiple quantitative traits based on marginal GWAS summary statistics. Genet. Epidemiol. 41: 427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do R., Willer C. J., Schmidt E. M., Sengupta S., Gao C., et al. , 2013. Common variants associated with plasma triglycerides and risk for coronary artery disease. Nat. Genet. 45: 1345–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek E. A., Jackson J. E., 1977. Statistical methods for social scientists. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hemani G., Zheng J., Wade K. H., Laurin C., Elsworth B., et al. , 2016. MR-Base: a platform for systematic causal inference across the phenome using billions of genetic associations. bioRxiv. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/12/16/078972.

- Kim J., Bai Y., Pan W., 2015. An adaptive association test for multiple phenotypes with GWAS summary statistics. Genet. Epidemiol. 39: 651–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Zhang Y., Pan W., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative , 2016. Powerful and adaptive testing for multi-trait and multi-SNP associations with GWAS and sequencing data. Genetics 203: 715–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak I., Pan W., 2016. Adaptive gene- and pathway-trait association testing with GWAS summary statistics. Bioinformatics 32: 1178–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak I., Pan W., 2017. Gene- and pathway-based association tests for multiple traits with GWAS summary statistics. Bioinformatics 33: 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Yang C., Gelernter J., Zhao H., 2014. Improving genetic risk prediction by leveraging pleiotropy. Hum. Genet. 133: 639–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Tsaih S.-W., Shockley K., Stylianou I. M., Wergedal J., et al. , 2006. Structural model analysis of multiple quantitative traits. PLoS Genet. 2: e114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar A., Haldar T., Witte J. S., 2016. Determining which phenotypes underlie a pleiotropic signal. Genet. Epidemiol. 40(5): 366–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson U. K., Fazio S., Linton M. F., 2012. Residual cardiovascular risk despite optimal LDL cholesterol reduction with statins: the evidence, etiology, and therapeutic challenges. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 14: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaid D. J., Tong X., Larrabee B., Kennedy R. B., Poland G. A., et al. , 2016. Statistical methods for testing genetic pleiotropy. Genetics 204: 483–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium , 2014. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511: 421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solovieff N., Cotsapas C., Lee P. H., Purcell S. M., Smoller J. W., 2013. Pleiotropy in complex traits: challenges and strategies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14: 483–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M., 2013. A unified framework for association analysis with multiple related phenotypes. PLoS ONE 8(7): e65245 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow D. I., Preiss D., Kuchenbaecker K. B., Holmes M. V., Engmann J. E., et al. , 2015. HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibition, type 2 diabetes, and bodyweight: evidence from genetic analysis and randomised trials. Lancet 385: 351–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teslovich T. M., Musunuru K., Smith A. V., Edmondson A. C., Stylianou I. M., et al. , 2010. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 466: 707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Auton A., Brooks L. D., Durbin R. M., Garrison E. P., et al. , 2015. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526: 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth P. P., 2016. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins as a causal factor for cardiovascular disease. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 12: 171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Rahman M., Jin L., Xiong M., 2016. A new statistical framework for genetic pleiotropic analysis of high dimensional phenotype data. BMC Genomics 17: 881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Yang C., Gelernter J., Zhao H., 2015. Pervasive pleiotropy between psychiatric disorders and immune disorders revealed by integrative analysis of multiple GWAS. Hum. Genet. 134: 1195–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Liu A., Mills J. L., Boehnke M., Wilson A. F., et al. , 2015. Pleiotropy analysis of quantitative traits at gene level by multivariate functional linear models. Genet. Epidemiol. 39: 259–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Sha Q., Zhang S., 2016. Joint analysis of multiple traits using “optimal” maximum heritability test. PLoS One 11: e0150975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer C. J., Schmidt E. M., Sengupta S., Peloso G. M., Gustafsson S., et al. , 2013. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat. Genet. 45: 1274–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The Cotsapas dataset can be downloaded from the online version of Cotsapas et al. (2011). The 2010 (Teslovich et al. 2010) and 2013 (Willer et al. 2013) lipid data are also publicly available at http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/public/lipids2010 and http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/public/lipids2013/, respectively. The R package for our new methods is publicly available at Github: https://github.com/yangq001/Plei.